INTRODUCTION

File folders, thousands of them, can be found in even the smallest of police stations. Typically, they’re housed in desk drawers, filing cabinets and vast rooms overseen by records clerks who are specially entrusted and trained for the task. The vast majority of the files that these men and women receive concern the mundane: incident reports, supplemental reports, accident reports, pawn tickets, warrants, arrest sheets, custody sheets, property sheets and on it goes. However, every once in a while, a clerk will handle files containing information that has made headlines the world over.

We outside law enforcement may have some idea, however skewed, of police work through the media and crime shows on television, but we remain largely unaware of the vast amount of paper that is consumed by criminal acts and subsequent investigations.

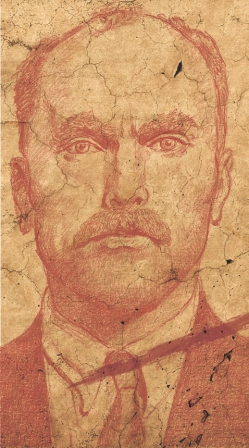

Consider the case – or cases – against Carl Panzram, as an example. His recorded criminal history begins near the close of the 19th century, when at the age of 8, he was picked up by police for being drunk in a public place. Over the three decades that followed, Panzram was arrested on at least eight other occasions. The multitude of crimes he committed, ranging from burglary and arson to rape and multiple murder, was investigated by a number of police departments. Files on his various crimes can be found in the states of Minnesota, Oregon, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maryland, Pennsylvania and Kansas. Panzram himself added a great deal of material to his files by writing an autobiography while in prison. This remarkable 20,000-word document is not only much more extensive and detailed than any of the confessions he’d previously provided for law enforcement officials, but it also contains information on crimes that had eluded investigation. Writing the memoir was, perhaps, the most honest act the criminal ever committed.

Panzram was eventually hanged for his manifold crimes. The last words he uttered were addressed to his executioner: ‘Hurry it up, you Hoosier bastard! I could kill ten men while you’re fooling around.’

This unpleasant encounter on the scaffold took place in 1930. Despite the efforts of a good many people – including Henry Lesser, a prison guard who befriended Panzram – it wasn’t until 1976 that the murderer’s memoir was allowed to be published. The Carl Panzram Papers, Lesser’s own collection of writing by and about the man, can be found at San Diego State University – yet another crime file.

Panzram, the earliest criminal covered in these pages, has something in common with the most recent, Anders Breivik, in that they both contributed damning writing to their respective files.

The latter’s 1,513-page 2083 – A European Declaration of Independence, provides details not only of his motives, but the considerable preparations undertaken in order to commit mass murder. Part-manifesto, part-confession, the document has also shown itself to be in large measure a work of plagiarism.

Breivik lifted whole sections from works that are properly attributed to the American Free Congress Foundation, far-right blogger Peder Jenson, and Unabomber Ted Kaczynski. However, charges of plagiarism don’t even register when placed beside Breivik’s other crimes.

In contrast to the Panzram manuscript, there was no decades-long wait for those curious about 2083. In fact, Breivik posted the entire document online just before he began his killing spree.

In this digital age, police departments routinely produce documentation on paper, while increasingly finding evidence in digital form. For example, in November 2009, disgraced Canadian Forces colonel Russell Williams left a threatening message on a victim’s home computer. Three months later, police searching the murderer’s Ottawa home uncovered several hidden flash drives that contained evidence of his crimes.

Stephen Griffiths, England’s self-proclaimed ‘Crossbow Cannibal’, had a very active online presence. Sitting in his bachelor apartment, calling himself ‘Ven Pariah’, he visited social networking sites, at which he described himself as a demon. Griffiths also maintained a macabre website, called ‘The Skeleton and the Jaguar’, devoted largely to serial killers. Two of his murderous attacks were recorded digitally. The most famous, captured by a closed circuit camera in the hallway of his block of flats, resulted in his arrest and was broadcast around the world. The second, a horrific scene, Griffiths recorded on his mobile phone. Viewed by only a few people involved with the investigation, the images were destroyed after the Crossbow Cannibal pleaded guilty and was sentenced.

The criminal acts here reach back nearly one hundred years. They begin at a time before most people had access to photography and end at a time in which murderers have Facebook accounts. Whether earlier days were safer days may be a matter for debate, but they were certainly easier to stomach.

John Marlowe

Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Carl Panzram