The Different Types of Detectors Available

If you have already started to take an interest in metal detecting, then there is a good chance that you will have come across one or more of the hobby’s magazines. Glancing through these, you may have been bewildered by the apparently staggering number of different machines that are currently available on the market.

Unless you have already acquired a metal detector, you will probably be wondering at this point which machine is most suitable for you. To help in making this decision you need to ask yourself the following:

How much am I willing to spend?

How much time will I devote to using my new detector?

How good am I at adapting to new technology?

All three questions, believe it or not, are closely linked. There have been many people who have jumped straight in at the deep end and purchased very sophisticated and expensive machines, only to find that they don’t understand how to use them. As a consequence, they either get sold or end up gathering dust in a cupboard having never had a sniff of a bit of silver.

Most detectorists begin either with a cheap basic model, or one costing little more than a couple of hundred pounds. With experience gained, they then usually trade up for something more upmarket.

If you’re unlikely to spend much time out in the fields then an expensive machine may not be a good investment. Saying that, of course, there have been occasions when fortunate prospectors have ventured out for the first or second time and found something worth more than the machine they have just purchased!

This actually happened to me (Dave Stuckey). After having purchased my first machine in 1976 at a staggering cost of £80, I took it out for its first trial and within minutes I found a solid gold pocket watch. The scrap value of the gold more than covered the cost of the detector.

To explain the differences between the different types of metal detectors available it is necessary to go a little into their history and development. (If some of the terms used are unfamiliar please see the Glossary included later in this book).

The first types of hobby metal detectors to become readily available in Britain in the late 1960s were BFO (Beat Frequency Oscillation) models. These were very basic and thus cheap and easy to produce….and buy. Most had two basic controls: on/off-volume, and tune. Tune consisted of setting the detector to a faint ticking noise that could be heard continually from the speaker (or headphones). When a target was located this ticking noise would increase in frequency. They had single coil open search heads, which made pinpointing a find difficult. Depth was seldom more than a few inches. They had no discrimination and would pick up nails, silver paper and ring pulls as well as wanted targets such as coins. They were also subject to drift and needed retuning every few minutes (or sometimes less!). Despite their primitive nature, fields, commons and other sites were “virgin territory” and some good finds were made by their users.

Several American detector manufacturers produced more advanced models of BFOs in the 1970s, but other designs eventually overtook these early machines. To my knowledge none are available new today although some may still be found at car boot sales or in junk shops. However, they are more of a curiosity and collector’s item than a usable piece of equipment.

The next model to become available in Britain in the early 1970s (although already established in the USA) worked on the IB/TR (Induction Balance/Transmit Receive) principle. These had two balanced coils in their search head, and would signal when a metal object disrupted their electromagnetic search field. Depth and pinpointing were a lot better than on earlier models. Although at first they did not have variable discrimination, some would naturally reject small pieces of iron or tiny fragments of silver paper. Most models, again, had two controls: on/off-volume, and tune. Tuning consisted of adjusting the control so that just a faint noise could be heard. When a target was located this would increase in volume. However, the problem remained of drift and the need for manual retuning when this occurred.

The problem was partially overcome with the development of push-button auto-retuning. This new control was a button that was held down while the detector was being tuned to threshold and then released. If the detector drifted from its pre-selected threshold point, all that was necessary was to push the button to bring it back to threshold.

Variable discrimination, which appeared at around this time, was another technological advance. Detectors of this type were usually referred to as: “TR/Discriminators”. Here a rotary control could be used to set the detector’s reject level to unwanted junk targets. However, the use of discrimination brought three disadvantages: it increased the detector’s susceptibility to mineralised ground; it caused loss of depth; and it meant that wanted targets were sometimes rejected alongside unwanted ones.

The next development, in the mid-1970s, was the VLF/TR (Very Low Frequency/Transmit Receive). Detectors of this type had, in effect, two separate circuits. One circuit, the VLF was less prone to mineralisation and could provide good depth. However, it was all metal and could not reject junk items. The TR side could discriminate but had less depth. Thus searching was carried out in VLF mode, and once a target was located the detector was switched to TR to establish if it was junk or a wanted find. The problem with this system was the need to switch back and forth between the two modes.

The invention that overcame this was meter discrimination. In detectors of this type both circuits were working at once, the VLF all-metal side controlling the audio while the TR discrimination side worked the meter. Thus all registered targets came through on audio but the meter needle swung left for junk, right for wanted targets. Further developments included variable discrimination on the TR side, and an overlay of tone on the VLF side (low for junk, high for wanted targets). On some models of this type of detector it is possible to select meter or tone discrimination, or both. Such detectors are still in production today and have proved very effective in the hands of their adherents, particularly on finding good targets amongst high levels of junk contamination.

Most detectors today are of the “motion” type that made an appearance in the late 1970s to early 1980s. Such detectors can overcome ground effect while discriminating at the same time by means of continually and automatically auto-tuning. At first the sweep speed had to be very fast, but further developments slowed this down to normal. To register a target with a motion detector the search head has to be in movement. If the search head is held stationary over a target the auto-tune circuitry will simply cancel it out. However, many motion detectors have an all-metal, non-motion mode for pinpointing and, even without this, pinpointing can be achieved quite easily as the coil movement required to register a target can be very slow.

During the mid to late 1980s computer technology began to be incorporated into metal detectors. In the same way that it is possible to programme a computer, it is now possible to programme certain detectors with a host of variables by means of an LCD screen and touch pad controls. These detectors come with basic “factory pre-set” programmes or you can devise and store a programme that you have developed yourself to cope with the conditions of a particular site. Some detectorists take readily to this new technology while others prefer simple “switch on and go” machines. Space does not allow us to go into further detail, but such detectors are – and will continue to be – fully covered in the hobby literature.

Fitting a scuff cover protects the search coil.

Early TR models.

An early 1980s detector working on the meter discrimination principle.

Hip or chest mounting a detector can save arm fatigue.

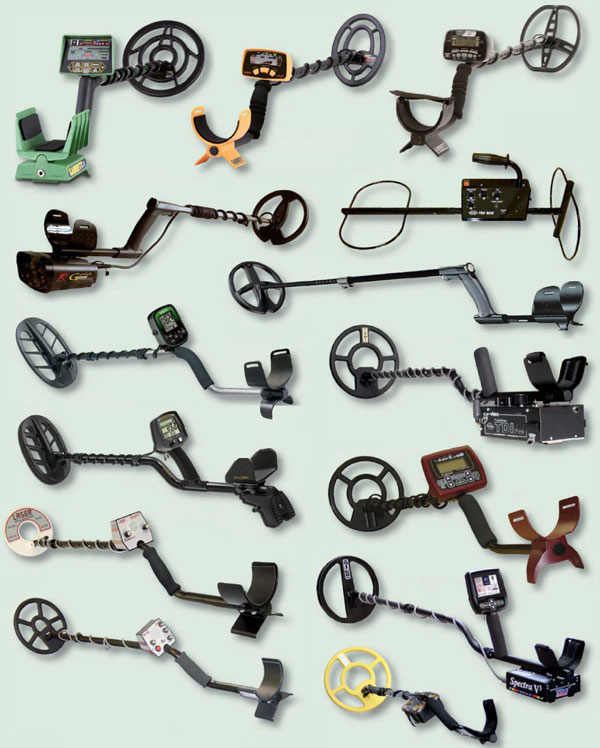

A Selection of Current Metal Detectors

In parallel to the developments described above have been those involving PI (Pulse Induction) detectors, first available to the hobby market in Britain in the 1970s. PI detectors put out a very strong electromagnetic field that energises metal objects buried in the ground and creates eddy currents around them. This makes such targets easier to detect. The system is virtually free from ground effect and Pulse detectors can be capable of above-average depths. However, PI detectors are sensitive to iron and many have no ability to discriminate against this or other types of metal. This makes them difficult – or often impossible – to use on inland sites. Battery drain is also often higher than with normal detectors.

Most modern detectors can operate quite well on wet sand on beaches if they have a “Beach” mode but Pulse Induction units are considered to be the best for this kind of site. The greatest advantage they have over conventional detectors is their greater depth-seeking capabilities and the ability to ignore mineralisation. Many come in waterproof cases that make them ideal for searching a beach down at the water’s edge and into the surf.

At present several new developments are underway, and PI machines are actually available that the manufacturers claim can be used on inland sites. Future evolutions in PI technology are worth following with interest.

With conventional detectors there is a broad spectrum of makes and models to choose from. There are relatively low-cost machines that are simple to operate and give reasonable performance. Following this, there are many models that are more sophisticated but cost several hundred pounds. These types of detectors offer very good performance, however, and are probably the most widely used.

Apart from the detectors mentioned above, there are also more specialised machines designed for underwater detecting and hoard hunting. The hoard hunting machines tend to be simply a large box with a coil at each end, and are designed to look for large targets, such as pots of coins, buried at great depths. They are, generally, less efficient at locating smaller targets nearer the surface.

Twenty-First Century Developments

The 21st century has seen some really good improvements to existing detector functions as well as build quality. Several leading manufacturer’s Research and Development departments have provided some astounding new technology. Some manufacturers now offer a new concept of development that is based on ground penetrating radar. Several of these have chest mounted digitally enhanced screens that show depth and in some cases simplistic shape of targets. It is fair to state that such developments are in a relative state of infancy, but there is no doubt that continued improvement will be available.

A final consideration is that of weight and balance. Some detectors are light enough for long hours of use by youngsters or by the infirm/elderly; others are heavier but with the application of a bungee style harness such weight issues are drastically reduced. Another way to overcome weight problems is to buy a detector with a detachable control box that can be belt or chest mounted, saving fatigue on the arm. If possible, “try before you buy”.