Making A Connection With Your Finds & Creating “Time Lines”

One of the most interesting aspects of this hobby is connecting with the finds you make. With very ancient artefacts this can truly stretch your imagination. You might find yourself asking questions such as: “What was the name of the person who last held this little Saxon sceatta?” or “What did he or she look like?” Perhaps you even create your own answers and write them in a log of your finds.

Although marvellous and mind stretching, historically such mental wanderings can never be factually based. What a shame that you will never meet the actual owner of that superb Roman enamelled brooch you have just uncovered. An even greater shame perhaps is that you are unable to meet that medieval moneyer who kept miss-striking those short cross pennies you find. Despite this, by simply finding the item you create a bridge across time connecting you to the person who lost the item. This is what we term a “Time Line”.

Technology – it is argued – may never be able to produce a functional time machine, but until it does the metal detector admirably fills the gap. However, there are finds of more recent times where you not only create a time line to a past loss but, if you are very lucky, you may meet the very person who experienced the loss, or direct members of his/her family. Examples of this are where wedding rings and bracelets etc are returned to their owners. I read recently of a named charm bracelet returned to its owner who lost it over 50 years before. You only have to read Treasure Hunting magazine to see how many rings and other treasured items of jewellery are found and returned to their very relieved owners.

Other examples of fairly modern losses send you on research projects that even a week before you may have had no particular interest in (i.e. the frequently found military buttons and cap badges). Metal detecting has created some phenomenal experiences for us that we feel privileged to have been involved in. For example, some years ago I was involved in organising the reunion of a Luftwaffe Flight Mechanic and the very RAF pilot who had shot him down in 1941. He had been part of the crew of a Junkers 88 on a raid to Birmingham in 1941 when he was intercepted. We learned later that, ironically, the RAF pilot had, by shooting down the German bomber, actually saved the life of its crew. This was due to the Flight Mechanic’s Staffel later being posted to the Eastern Front. No one came back alive from that venture.

You can imagine how emotional this meeting was, as they proclaimed each other “brothers of the air”. It was made all the more remarkable for me as, due to an earlier metal detecting search of the spot where the Junkers crashed, I was able to hand back to the flight mechanic one of the spanners from his on-board tool kit.

Another incident springs to mind when I was metal detecting the crash of a Heinkel He 111 bomber shot down in 1940. Finding lots of interesting pieces, I later sent some to the original pilot now living in Canada. This pilot sends me a Christmas card each year. Every time I read a book on the Battle of Britain and see him mentioned, it means more than just a name in the text.

It gives you such a sense of achievement to be involved at this level, and to be able to do such things is a true honour. I will never forget the time when a Mosquito pilot was telling me about when the whole starboard wing of his aircraft suddenly broke away, and he was literally sucked out of the damaged cockpit. “The last thing I saw, boy, was the altimeter needle going haywire”. Later we organised a small excavation of the site where his aircraft had crashed. Fortunately, the pilot was able to attend, and was fascinated with the day’s events. A lot of luck and the use of a metal detector allowed me to present him later that day with the very same – although somewhat battered – altimeter. You simply should have seen the look on his face. Sadly, the young navigator was killed in this crash, and as a mark of respect we asked the local vicar to hold a service at the site of the excavation. This was duly done, and at the end of the day a sapling oak tree was planted exactly on the impact spot.

Once I found a tiny piece of brass inscribed with the name “Lady Bearstead”, and an associated address. Photographing the artefact, and later including in it in a Treasure Hunting article led to additional research and the later receipt of an interesting letter. This letter was from an elderly gentleman who actually remembered Lady Bearstead in the 1920s, and went on to give me a full Bearstead family history. It would seem Lady Bearstead’s husband was a wise investor. In the 1890s he bought virtually all the shares in a small petroleum company and reinvested further; the company did rather well, and today is known as Shell.

We have chosen two metal detector finds of reasonably modern date, which we feel illustrate time lines and often fascinating research that is associated with them. This is, of course, combined with the exciting possibility of meeting or corresponding with the owner or relatives.

Find 1

Fig. 1. The plaque was folded in half when first found.

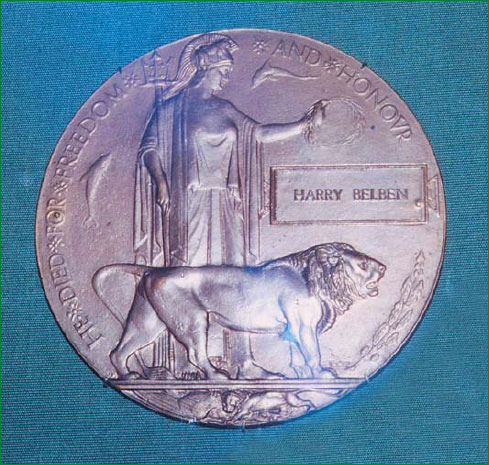

Fig. 2. A similar plaque in the Luton Museum.

While searching in an isolated field in the heart of Bedfordshire, I unearthed a very large bronze disc. The disc was heavily corroded and had been bent in half, presumably from being struck by a ploughshare. Although seemingly uninteresting, I kept the disc and took it home with me, where it was consigned to a box containing many other items of metal “junk” that I had accumulated over recent years.

A year or so later, while sorting out this “junk”, I picked out the disc and almost threw it away. Fortunately, I had the sense to examine the disc more closely before doing so. Holding it up to the light, I began to make out details of a figure – most of which was obscured as a result of the disc being bent double. I decided to make an attempt at straightening out the disc in order to try and see what the figure actually was. After doing so, I soon found that it was, in fact, a large plaque depicting a classical figure standing beside a lion. I had no idea what the plaque or medallion represented but I was soon enlightened after a visit to a local museum. In a glass case, along with many other medals and plaques, was one identical to that which I had found. I noticed, also, that the plaque bore the name of a soldier who had been killed in the First World War. When I later returned home I examined my own plaque to see if it, too, bore any inscription. After some careful cleaning I could make out a man’s name. The disc now took on a whole new meaning. No longer was it a piece of corroded and twisted “junk” – it now represented a man’s life.

Searching through a list of names of soldiers who had died in the Great War, compiled onto a CD Rom, as well as visiting two Internet Websites, revealed an astonishing story….with a puzzling twist in its tail. The soldier’s name did appear on the compiled list, along with his Regiment, serial number and the day he was killed. However, when cross-matched with names listed with the War Graves Commission, I soon discovered that the name on the plaque wasn’t the man’s real name. Now armed with the soldier’s real identity, I was able to learn that he had been a greengrocer who lived at Carshalton, in Surrey, before enlisting in the army. His surviving relatives continued living at his home address until the 1960s, but no further trace could be found.

I also learned, from reading the Regimental Diaries, that he was one of three men who had been killed while searching a building in Arras, in 1917. The building was hit by artillery fire. For many weeks, this man’s story had become a part of my life. I had managed to find out who he was, where he lived, and how he died. The two puzzles I have yet to solve. Why did he change his name when he joined the army? And perhaps even more intriguing, how did his memorial plaque end up being buried in an isolated field in Bedfordshire 40 or 50 miles from where he and his family had lived?

Find 2

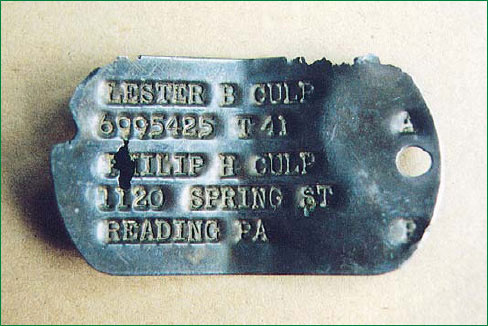

Fig. 3. The identity tag of Lester B. Culp, who died on the “Peacemaker” B17 bomber.

For many years I have been fascinated with the crash of several B17 bombers around the village of Weston in Hertfordshire. One of these, which was named “The Peacemaker”, crashed on a training flight in 1945. Having obtained the crew names, somebody suggested I use one of the name-tracing Websites, to see if any relatives still lived in the USA.

Basically, all I had was a surname and place of birth. Would anyone still be there after 60 years? Perhaps the family had died out or moved away. The Website revealed 15 people with the same surname, so I sent a mail shot to them all. Nothing happened for a few weeks and then a solitary letter arrived. Amazingly it was from the younger brother of one of The Peacemaker’s crew, all of whom had been tragically killed. He later went on to send me press cuttings, family photographs and a whole history of family events.

For many years I have metal detected where The Peacemaker crashed, collecting some small twisted fragments and several bullet cases. Then one day another detectorist appeared on the site, also passionately interested in such wartime happenings. We had a good old chat and then carried on our separate searches

A few weeks later I received a telephone call from him stating he had found something very unusual. Later we met up and unusual his find certainly was: he had found the dog tag of the crewmember whose family I had traced in the States. I managed to persuade the gentleman that, in the light of the fact that I was already in contact with relatives, we should arrange to return the dog tag. This was duly done, and resulted in one of the most passionate thank you letters I will ever receive.

One off shoot of this find was that through correspondence with the brother I discovered that the hometown of his family in the States is famous for producing pretzels. It was my turn to be surprised a month or so after when a huge 10k presentation of the aforementioned snacks was delivered by courier to my doorstep. As a young boy of approximately 10 when I first heard of this B17 crash, I could never have believed that in three decades time I would be in contact with the family of one of the crew.