They were all there, the plump men in their dickie-bows, the women glinting with sequins and spite, rattling their jewels at one another and casting acquisitive eyes over the list of auction items for later. The usual things were up for grabs: the golf weekends and wing-walking opportunities that would be re-donated to another charity as soon as the winning bidder sobered up, the dinners at expensive restaurants hungry for promotion, the handbags donated by designers fashionably doing their bit for the environment, for the fluffier of God’s soon-to-be extinct creatures, for children, for Africans, for whatever.

Olivia felt at home on the usual spindly gold chair, her breasts nestling in her dress, displayed for all the world like a couple of Easter eggs in novelty egg cups. She milked her friend Sabrina for the grislier details of a recent weekend in Gloucestershire to which Olivia had not been invited.

‘…and the children! The girl—who is not a looker, by the way—wouldn’t let Julia finish a single sentence and the boy had to be sent to his room for slipping worms onto the barbeque.’

‘Oh yuck…’ Ever since she’d been widowed Olivia had found herself left off the guest lists of all the jolly occasions. She took it as affirmation of her own attractiveness in the eyes of the other wives.

The croustade of quails eggs came and went, the man on her left sloshed Pouilly Fume into her glass. ‘Not such a bad vintage,’ he said with yolk yellowing the cracks at the corners of his mouth. Olivia rather hoped he wasn’t so well brought up that he’d feel impelled to turn away from his companion to make conversation with her for the duration of the next course, which was, quite predictably, to be salmon.

‘They only discovered what he’d been doing with the worms after everyone had eaten their lamb burgers,’ Sabrina was saying. ‘Revolting. I was nearly sick.’ She waved a hand at the floral arrangement in the centre of the table: ‘Why do you suppose they always put things like vegetables in there? Artichokes? Are they trying to surprise us?’ dismissing the flowers while Olivia watched the diamonds flare at her wrist. ‘Mistress present,’ said Sabrina catching her eye. ‘So much better than anything he ever bought me after we were married.’

The pudding, a concoction of white chocolate mousse and crushed raspberries in a gilded cage of spun sugar, was left untouched by both women. The man who had been so enthusiastically refilling her wine glass claimed to have once been a drummer in a rock band. She and Sabrina found him just a little bit interesting after that. As the coffee and petit fours arrived a woman whose Minnie Mouse voice rendered her unsuitable for public speaking took to the podium to introduce the guest speaker. ‘It is because of people like Daniel Flint that the trade in Indian Tiger products has been brought to light,’ she squeaked. A juddery video was being shown of tiger skins being shaken out on dusty streets. The swerving camera picked out a shelf of bottles. Chinese characters in gold, a translation in bold type, and no, it wasn’t a mistake: “Tiger wine” printed on the labels.

‘Oh, how awful,’ Sabrina said, reaching for a tiny square of fudge and then thinking better of it, as a tall man with shoulder length dark curls bounded on to the stage.

‘Who’s that? Lord Byron?’ said the drummer but the women were not listening to him any more.

Daniel Flint spoke in a voice as rich and dark as pure Arabica. His surveillance team had taken many risks concealing cameras in brief cases, posing as businessmen, meeting the illegal traders late at night and bringing back footage that more than hinted at corruption and links to government agencies.

‘I know that you’re here to have a good time and straight after the auction the band will be on but I ask you please not to ignore the envelopes that have been placed on the tables before you,’ he said, and before he had finished speaking Olivia was unsnapping her bag, which was too small to hold a chequebook, hoping her credit card would do. ‘Your donations will make a difference.’ Daniel Flint seemed to look straight at her and she felt herself grow hot. ‘Your donations will fund our work to expose this illegal trade.’ And then, still looking at her he thumped the lectern: ‘If we don’t act now the Indian Tiger will be wiped off our planet within the next decade.’

Oh it was shameful! By the following evening, the artichokes that Daniel Flint had salvaged from the floral arrangements were bobbing about in a pan of salted water in Olivia’s Holland Park kitchen, and they were both still laughing as she opened the second bottle of wine.

He had noticed her almost immediately: she was hard to miss with that hair and those legs. He had picked out the drummer whose band had provided the soundtrack to his youth, and there she was staring up at him with huge doe eyes, twisted around in her chair, blonde hair lustrous around her shoulders and falling in thick waves against the emerald sheen of her dress.

She’s wearing a loose silk blouse this evening. Her amber eyes glisten, he sees tears wobble and spill as he tells her about the things he’s seen. The carcasses: so many of them. The bones with bits of tiger skin still attached that are suspended in the bottles of rice wine. ‘Like the worms in tequila,’ she says, twisting her hair. ‘Much worse.’

‘Oh yes, I didn’t mean that…’

He reaches over and touches the sweet tip of her nose where a little butter has made it shine. ‘And the tiger’s nose leather is used to treat wounds,’ he says. His fingers move to the top of her head. ‘The brain is ground into a paste for pimples.’ He kneels at her feet, takes her hands in his. ‘The claws are used to cure insomnia…’ Her nails are lacquered bright red and he kisses them one by one. She smells deliciously of aniseed.

She woke shivering from the strangest dream. Daniel Flint lay stretched out beside her, one arm thrown across the pillow, palm upwards as though waiting for something to be placed into it, the other lost beneath the sheets. He was smiling slightly in his sleep in a way that made her envy whatever was going on in there. Her own dream hadn’t been so bad, just odd: she had been tiptoeing through the snow on a high silvery plateau, wrapped in soft furs, a tiny fawn-like creature on wobbly legs beside her, nibbling and nuzzling her, looking up at her with liquid brown eyes, and in the dream she knew that this was her baby, and that just out of sight Daniel was standing, sniffing the air for danger, guarding them. She steals another look at him across her pillow: his nostrils flare slightly, his eyelashes and brows are so dark they appear to have been sketched and smudged on to his face with charcoal. It seems impossible that such a beautiful specimen is lying in her bed. It’s like finding a Faberge egg in a junk shop.

She tiptoes from the bed. Moonlight floods the room as she slides back the curtains and she can smell the night-scented jasmine that winds its way from the garden to her window, but still she can’t shake her chill. Daniel stirs slightly in his sleep, mutters something that sounds like “beloved,” and turns his face into the pillow. Olivia can’t stop smiling as she wraps herself in her shahtoosh and wonders at her strange dream. How can it be that a mere vision of a snowy wasteland can make her feel so cold on a summer’s night?

She slips back into bed, shivering despite the shawl, her beloved “toosh” given to her on her wedding night, and the envy of all her friends. The fine faun-coloured cloth so wondrous it was said that a pigeon egg would hatch if it were to be wrapped in it. ‘There,’ her husband ran the miraculous bolt right through the centre of her wedding ring. ‘The real thing. I won’t tell you how much it cost.’

Daniel wakes with a dry mouth and Olivia’s sheets tangled around his legs. He reaches for her across the bed and his fingers snag against something soft. He slides his eyes sideways and even in the pinkish dawn he fears that he knows only too well what it is she has wrapped around herself.

He turns onto his elbow and gingerly rubs a piece of the cloth between his finger and thumb: it is unmistakably a shahtoosh, made from hairs so fine that whoever wove it had probably gone blind.

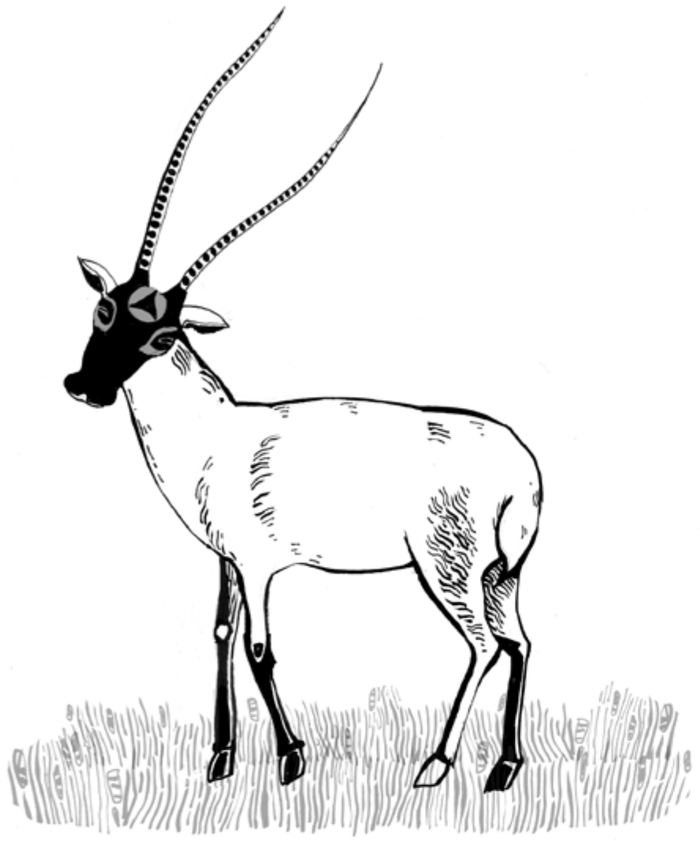

A small snore escapes from Olivia’s mouth, and with it a sour smell. Stupid woman! He doesn’t know if he wants to shout at her or run away. Both probably. He wonders if she’s one of the brainless ones who believe these things were fashioned from the shed breast feathers of the fictitious Tooshi bird, but doubts it. The newspapers have been full of this fashion scandal: the massacre of four young Chiru antelopes for every shawl. He stands from the bed and bends down over her, just to be sure. He should wake her up and tell her how the chirus died for her: caught in the headlights and gunned down, or with their legs bitten through by the teeth of a barbarous trap. He should tell her how soon these beautiful creatures will become extinct and how it will be a double tragedy since the chiru’s fleeces are carried over the mountains to the Indian border and bartered for Tiger parts: India trading with China so that every shahtoosh has the blood of a tiger upon it. But the nausea he feels is rising from his stomach and burning his throat and she doesn’t smell so good to him now. A breeze sucks at the curtain and shadows fall across her face. She had seemed almost radiant to him the night before, with her trembling tears and righteous indignation; he would have been happy to die in her arms; but now he can see that it was all artifice. If he tugged hard enough the blonde tresses would probably come off in his hands and there is something unnatural about the curve of her cheek, in the tightness of her jaw and in the way her brow remains mysteriously untroubled. He grabs his things, leaving her lying beneath her shroud, and finds his way out and into the morning.