3 Strategy

Hail, ye indomitable heroes, hail! Despite of all your generals ye prevail.

—Letitia Elizabeth Landon

Abraham Lincoln was worried that the northern people had still not made up their minds that the war was in earnest. “They have got the idea into their heads that we are going to get out of this fix, somehow by strategy!” he told a group of Sanitary Commission volunteers in early November. “General McClellan thinks he is going to whip the rebels by strategy; and the army has got the same notion. They have no idea that the war is to be carried on and put through by hard, tough fighting... and no headway is going to be made while this delusion lasts.”1 The recent elections convinced the president that too many people did not grasp the war’s awful calculus. As news of the Republican defeats sank in and rumors of foreign intervention spread, the president increasingly vented his frustration on White House visitors.

“He has got the slows,” Lincoln testily remarked after McClellan allowed Lee to slip between the Army of the Potomac and the Richmond defenses. Slow: that one word described the Army of the Potomac’s commander perfectly. As the president’s secretary John G. Nicolay explained, Lincoln admired McClellan’s abilities, and his “high personal regard” had led him to “indulge” the general’s “whims and complaints and shortcomings as a mother would indulge a baby.” Despite the Democratic campaign to elevate the “Young Napoleon” to a national hero by a “most vigorous and persistent system of puffing in the newspapers,” McClellan had never lived up to his reputation. He was “constitutionally too slow, and has fitly been dubbed the great American tortoise.”2

Lincoln had solid military reasons to get rid of McClellan, but political imperatives had momentarily stayed his hand. Timing, Lincoln well knew, in both political and military affairs was everything. So just as he had waited to replace Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell in the western theater until after the October states had voted, he hesitated now to move against the popular McClellan before the New York elections.3 On November 5, with Seymour’s victory certain, the president at last ordered Gen. in Chief Henry W. Halleck to remove McClellan and appoint Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside of the Ninth Corps to command the Army of the Potomac. Fearing that McClellan harbored Caesarean ambitions and might defy the administration, Stanton took the precaution of sending Brig. Gen. Catharinus P. Buckingham, an older staff officer who had graduated from West Point with Robert E. Lee, to deliver the president’s order.4

Around ten on the evening of the fifth, Stanton summoned Buckingham to the War Department. Entering the secretary’s third-floor office, Buckingham ran into Halleck and, ironically enough, General Wadsworth, who had just lost the New York governorship to Seymour. Stanton led Buckingham into a small room and handed him two envelopes, one addressed to McClellan, the other to Burnside. The general was to make sure that Burnside accepted the command first, and then he was to deliver the order to McClellan in person. Should Burnside absolutely refuse the command, Buckingham was to return to Washington without seeing McClellan.5

Buckingham arrived at Ninth Corps headquarters south of Salem, Virginia, on November 7 toward evening. Finding Burnside asleep in an upstairs room of a small frame house, Buckingham awoke the general and handed him the momentous envelope. Burnside “did not feel competent to command and [stated] that he was under very great personal obligations to McClellan,” Buckingham later reported. Prepared for just such a reply, Buckingham played his trump card: if Burnside refused the appointment, it would be offered to Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. Even the genial Burnside considered Hooker a dangerous and unprincipled intriguer, and so he reluctantly acceded to Lincoln’s wishes.6

Buckingham, Burnside, and two aides traveled through a snowstorm back to army headquarters at Rectortown. The night had grown bitterly cold as they reached McClellan’s tent around 11:30 P.M. Having just finished a cup of tea with Brig. Gen. Herman Haupt, the superintendent of military railroads, McClellan had begun writing a letter to his wife, Ellen. Buckingham and Burnside knocked on the tent pole.

As McClellan remembered it, the two men looked “very solemn” but tried to make polite conversation. Buckingham, however, recalled nervously blurting out the purpose of the visit and thrusting the envelope into McClellan’s hands. McClellan read the orders and then calmly remarked, “Well, Burnside, I turn the command over to you.” Little more than a month later Burnside vividly recalled the shock: “I then assumed the command in the midst of a violent snow-storm with the army in a position that I knew but little of.”

After Burnside and Buckingham left, McClellan resumed the letter to Ellen. “I am sure that not a muscle quivered nor was the slightest expression of feeling visible on my face, which he [Buckingham] watched closely. They shall not have that triumph,” McClellan wrote proudly. Toward his successor, he was condescending: “Poor Burn feels dreadfully—I am sorry for him.” Typically, McClellan had only arrogant disdain for his superiors: “They have made a great mistake—alas for my poor country—I know in my innermost heart she never had a truer servant.”7

McClellan’s disappointment and anger quickly surfaced. On November 9 he told a staff officer that death seemed preferable to leaving his army in another’s hands. He voiced similar sentiments at an officers’ reception that evening: “I feel as if the Army of the Potomac belonged to me. It is mine. I feel that its officers are my brothers, its soldiers my children. This separation is like a forcible divorce of husband and wife.”8

It was not a wholly inapt analogy. Many officers and enlisted men reacted to news of McClellan’s removal with the despair of a jilted lover. “The army is in tears,” declared a Pennsylvania captain. Those who had served with the general through several campaigns were especially distraught; even in the newer regiments, men expressed regret.9 Demoralization seemed inevitable. A foreboding of impending disaster hung over the camps; the most disgruntled no longer appeared to care about the Union’s fate. A Pennsylvania recruit expected the Army of the Potomac to be driven out of Virginia and Confederate independence established. Some soldiers were temporarily overwhelmed by an utter hopelessness.10

The initial shock soon gave way to spirited indignation. “There is one opinion upon this subject among the troops,” Brig. Gen. John Gibbon, the able commander of the Iron Brigade, asserted, “and that is the Government has gone mad.” The president had treated a skillful and selfless patriot contemptibly. Unable to comprehend the decision, the men engaged in what a Minnesotan described as “tall swearing.” Regimental letters to local newspapers dramatically conveyed the uproar to the home folks.11

Soldiers always complain, of course, but the anger ran much deeper than the usual grousing at the end of a hard day. The more outspoken officers threatened to resign their commissions. Empty blustering or not, at the time it appeared serious.12 “Lead us to Washington,” one general supposedly begged McClellan, and “we will follow you there.” Reckless talk came easy, and there is no evidence that any of this vexation ever got beyond the talking stage; but disaffection clearly infected the army’s upper echelons. Brig. Gen. Andrew Atkinson Humphreys, a longtime McClellan supporter with a legendary penchant for profanity, reportedly spouted that he “wished the Confederates would get into Washington and drive the whole d—d abolition posse into the Potomac.” The Maine soldier who recorded this incident noted how many high-ranking officers adamantly insisted on McClellan’s restoration to command: “No stone is left unturned to keep alive this feeling of distress among the privates and lower-grade officers.”13

With no encouragement from their hero, however, most soldiers could do little but gripe, though some veteran officers did try to leave the service. A Rhode Island sergeant who deemed McClellan’s departure “the hardist blow this Armey ever had” regretted that enlisted men could not resign.14 As it turned out, however, neither could their officers. A general order from the War Department forbade any officer from resigning in the face of the enemy. Strongly appealing to patriotism and ethnic pride, Brig. Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher of the famous Irish Brigade reminded his disgruntled men that they fought for a cause, not for an individual. Adj. James B. Thomas of the 107th Pennsylvania would stay in the army only “because I have taken an oath to do so. . . . Before I think I had a higher motive.”15

For many others the “higher motive” was exactly the point. The soldiers in the Army of the Potomac would remain steadfast even if they strongly disagreed with the government’s military policies. However grudgingly, the men would respect Lincoln’s authority as commander in chief. “The American soldier is true to his country, true to his oath, and resolved to fight the rebellion to the bitter end no difference who commands,” a member of the 6th Wisconsin maintained. “[I] am not a McClellan man, a Burnside man, a Hooker man, i am for the man that leads us to fight the Rebs on any terms he can get.”16 Soldiers repeatedly noted the simple imperative to obey orders. Denying stories that the Army of the Potomac had become demoralized, Republican newspapers reported the men eager to meet the enemy in battle.17

Some soldiers in fact welcomed the change in command because, like Lincoln, they had gradually lost confidence in McClellan as a fighting general. They readily recalled the spring fiasco on the Virginia Peninsula and could easily tick off the mistakes made during the recent Antietam campaign. Unable to understand why they could not whip the ragged Rebels, they blamed McClellan’s lack of aggressiveness. A sarcastic Indiana veteran wondered why the Young Napoleon, despite abundant opportunities, had not yet “given some evidence of military genius.” Campfire arguments erupted between McClellan’s staunch defenders and his now emboldened detractors.18

Many bluecoats, of course, occupied the broadly confused middle. Refusing to embrace the blind devotion of McClellan’s friends or the equally fanatical hatred of his enemies, they often sounded painfully ambivalent. Contradictory reactions appeared within a single paragraph of a single letter; soldiers kept changing their minds about McClellan’s departure for days or even weeks. As a Pennsylvania captain later put it, he and his comrades felt like a young man who loses his lady love, suffers exquisite agony, but then decides there are other women in the world.19 Such sentiments were easily enough expressed, but many officers and enlisted men worshiped McClellan. For better or for worse, those affections would not fade so quickly.

While some generals command fear or respect, McClellan inspired lasting devotion. Soldiers explicitly described their “love” for Little Mac, an attachment comparable to the admiration of the French for Napoleon. Not even George Washington had been so beloved by his men. One disheartened engineer referred to McClellan simply as “our Georgy.” Sounding like a young man writing to his father, a New York colonel told the general how he had “grown up under your care.” For weeks after Burnside took command, soldiers sitting around the campfires at night would sing, “McClellan is the man.”20

True believers clung to an unswerving faith in McClellan’s military genius. No other general would ever command such devotion from so many soldiers in the Army of the Potomac.21 “Confidence” was the word that most often appeared in diaries and letters, and to men with such confidence it quickly became an article of faith that McClellan would have led them to victory had he not been shamefully removed. To sack a successful general in the midst of a march into enemy territory appeared the height of folly. The “idol of the Army,” as a New York private dubbed McClellan, would surely have captured Richmond.22 Whether the Army of the Potomac would ever have such faith in another commander remained an open question. Hotheads swore they would never fight for anyone but their beloved Little Mac.23 Such sentiments may have made Burnside nervous, though it was difficult to gauge their significance. Most soldiers would do their duty; but the effects in the army would be lasting, and the political consequences for the Lincoln administration were potentially devastating.

Rather than criticizing the president, however, many men simply cursed what a Massachusetts recruit termed “wire pulling politicians” trying to manage the war from Washington. If only such schemers would leave their comfortable offices and take the places of the long-suffering soldiers. The boys had grown tired of being “dupes and tools of mad politicians,” a Wisconsin sergeant groused, and were counting the days until their terms of enlistment expired.24 “Patriotism no longer rules but fanaticism,” a Michigan private protested. Abolitionists, the culprits who had supposedly pressured Lincoln into dismissing McClellan, became convenient scapegoats. “It was nothing but the nigar lovers of the North who took him from us,” a Pennsylvania private concluded.25

Yet even McClellan’s most fervent supporters realized that their hero had been steadily losing popular favor, especially among civilians who considered many generals too cautious and blithely spoke of conducting a winter campaign. These critics were “men who have no spunk enough to leave their mammy long enough, let alone to face the enemy,” Pennsylvania private Alexander Adams railed, “men who are setting on their asses by their warm fires and enjoying all the comforts of home, running down men who are enduring hardships all the time and risking their lives to restore their country.”26

McClellan had polarized both the country and the officer corps, turning the Army of the Potomac into a hothouse of intrigue. To Republicans McClellan’s popularity in the ranks had been greatly exaggerated. Only the general’s closest associates and what a Wisconsin soldier (himself just elected to Congress) called “political Generals of the Fernandy Wood school” would regret the Young Napoleon’s departure. McClellan himself may have been a loyal man, a Regular army officer commented; but the “election of the New York traitors; the gallows-birds who have damned McClellan by befriending and admiring him” had led to talk of dictatorship, and this had spelled the general’s doom.27 So he would leave, mourned by many but scorned by others.

Little Mac seemed oblivious to the latter. In a typically egotistical address he recalled how the Army of the Potomac had “grown up under my care.” After praising the men’s loyalty and sacrifices, he added a final sentence that must have pleased his Democratic friends: “We shall ever be comrades in supporting the Constitution of our country and the nationality of its people.” Privately he was less discreet. During one farewell visit with some officers he proposed a presumptuous toast: “The Army of the Potomac, God bless the hour I shall be with you again.” He had to hold back tears as he bade goodbye to old friends.28

Burnside had graciously arranged for McClellan to review the troops one last time. The men, often several ranks deep, lined the roads for more than three miles near the army’s newly established Warrenton headquarters. By eight in the morning on November 10 the men of the First, Second, and Fifth Corps, with bayonets gleaming and artillery scattered along the route, waited to catch a final glimpse of their hero. McClellan rode a fine stallion with his staff trailing behind, but occasionally the soldiers broke ranks to gather around him.29 Even amid the boom of cannon, the cheers from these bareheaded veterans seemed deafening. Men wildly tossed caps into the air, officers saluted with swords, and color-bearers waved tattered regimental flags.30 Some old soldiers wept. Even men who acknowledged McClellan’s faults broke down under the strain of intense emotion. “The Army of the Potomac has just returned from its funeral,” a private in the Fifth Corps somberly remarked. Some men cheered and sobbed and fumed at the same time, their oaths and threats rent the air, and their denunciations of political stay-at-homes occasionally exhausted profane vocabularies.31

In some units, especially the newer ones, nobody cheered, and McClellan did not even review Burnside’s old Ninth Corps. One New York veteran sourly refused to shout for McClellan and instead wished he were back home.32 Some soldiers stuck to their accustomed pose of scornful indifference. A Pennsylvania corporal wondered why anyone considered McClellan, Burnside, or any other general better than ordinary mortals. An orderly in Hancock’s division took much more interest in breakfast than in the “rise and fall of generals.”33

Yet few officers and enlisted men could be so cavalier about such a dramatic change. McClellan himself struggled with deep emotions. He rode along sadly surveying the troops and could not keep from weeping. “I never before had to exercise so much self control,” he commented in a hastily scribbled note to Ellen. “The scenes of today repay me for all that I have endured.”34 The next morning a red-eyed McClellan and several of his staff prepared to leave for Trenton, New Jersey. His uneventful departure from the army relieved nervous Republicans, perhaps prematurely. Democratic kingpins soon bought the general a fine house on West 31st Street in New York and began touting him as a presidential candidate. Calling for an armistice and a negotiated settlement of the war, peace advocates loudly praised Seymour and McClellan.35

No sooner had McClellan left the army than the political fireworks began. Democrats seized every opportunity to use McClellan against the administration. Comparing Little Mac to George Washington, the New York Herald praised him as a “great general and perfect patriot” who had been “mostly falsely and basely maligned and abused.” McClellan’s military genius was as obvious as Lincoln’s ineptitude. Why had the abolitionists pressured the president into recklessly removing the general on the eve of a great victory? McClellan was just the latest “sacrifice” to “appease” what New York congressman Samuel S. Cox termed the “ebony fetish.”36

For their part abolitionists rejoiced that the great obstacle in their war against slavery had at last been removed. Through Charles Sumner’s rose-colored glasses, McClellan’s dilatoriness now appeared providential. It had ensured that the rebellion would not be defeated before slaves were declared free. Buell had departed and now McClellan. Apparently the administration’s infatuation with conservative generals was over; surely there would now be no retreat from emancipation.37

Although both Democrats and abolitionists exploited Lincoln’s decision for their own purposes, political considerations cut in several other directions. McClellan’s removal heartened Republicans regardless of their factional loyalties and thus boosted Lincoln’s standing in the party. “The country will breathe freer,” a Racine, Wisconsin, editor predicted, “when it learns that this prince of laggards, not to say traitors, has at last been removed from the command of the Army of the Potomac.” If anything, the president had been far too patient with someone who had let the Confederates escape repeatedly from his grasp. In rural Republican strongholds the press heartily agreed that Lincoln had acted none too soon.38

Denying Democratic charges that McClellan had been shelved because of his political views, Republicans insisted that the president had made a strictly military decision. Even Seward’s conservative friends welcomed Little Mac’s departure. Privately Republicans speculated that the recent elections may at last have given Lincoln some backbone. Had the president moved sooner, the party might not have suffered such heavy losses, but few Republicans cared to dwell on past mistakes. Instead they looked to the future, hopeful about the prospects of a more aggressive military strategy.39

A few editors and politicians sounded as ambivalent as some of the soldiers about the change in command. Quietly sustaining Lincoln’s course seemed wisest, but conservative and moderate Republicans remained uneasy about where the war might be heading, and for good reason.40 Lincoln had made a risky decision. Whether Burnside or anybody else could lead the Army of the Potomac any more successfully than McClellan was by no means clear. Certainly no one matched McClellan’s organizational talents and ability to inspire devotion. Neither Lincoln nor Halleck had been able to impose their strategic ideas on the army’s recalcitrant generals, many of whom were Little Mac’s allies. McClellan had shown signs of learning how to deploy his magnificent army in battle, but his slowness, excessive caution, constant complaints, loose talk, and near-insubordination had tried even Lincoln’s legendary patience.41

That McClellan had been about to win a dramatic victory over an increasingly confident Robert E. Lee, as the general’s admirers would always believe, was a doubtful proposition. Yet installing a new commander in early November meant several weeks’ delay, pushing any campaign late into the fall, when inclement weather could stymie the best-laid plans. For Lincoln the choice of McClellan’s successor had posed no end of difficulties.

Many Republicans would have welcomed the appointment of “Fighting Joe” Hooker. While in Washington convalescing from a painful foot wound suffered at Antietam, Hooker had courted several influential politicians, including Salmon P. Chase and his politically ambitious daughter, Kate. Criticism of McClellan’s sluggishness and possible disloyalty quickly became their chief topic of conversation. Hooker’s endorsement of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation greatly pleased the radicals, and by late October many people in Washington expected him to supplant McClellan. Yet Lincoln knew about Hooker’s reputation as an intriguer and McClellan hater. His loose, indiscreet chatter had done nothing to endear him to either the president or Halleck.42

Hooker’s liabilities then made the appointment of Ambrose E. Burnside seem prudent. Born in Liberty, Indiana, on May 23, 1824, Burnside had worked for a time as a tailor’s apprentice. He received an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where unlike his future opponent Lee, he accumulated scores of demerits. The convivial proprietor of a local saloon regularly drank toasts to the three men he admired most: St. Paul, Andrew Jackson, and his favorite customer, Ambrose Burnside.43 Although he narrowly escaped disciplinary dismissal, Burnside compiled a respectable academic record and in 1847 managed to graduate eighteenth in a class of thirty-eight cadets. He covered himself in gambling debts rather than glory during subsequent service as an artillery officer in the Mexican War. Assigned to an isolated post in New Mexico, he fought boredom by designing a breech-loading carbine for the cavalry. Burnside married Mary Richmond Bishop from Providence, Rhode Island, in 1851 and two years later resigned his commission to begin manufacturing his carbine. For various reasons this business failed, and by the eve of the Civil War he was working as a cashier for a railroad owned by none other than George B. McClellan.

Shortly after the bombardment of Fort Sumter, Burnside accepted command of the 1st Rhode Island infantry regiment. His leadership of a brigade at the First Battle of Bull Run earned him a quick promotion to brigadier general. Burnside’s first opportunity for independent command came in January 1862 when he directed an amphibious expedition that captured Roanoke Island off the North Carolina coast. Success against greatly outnumbered Confederates had come when Union victories were scarce and by March had earned Burnside another star. Clearly he seemed destined for higher command, but his flaws as a general had already emerged. He delegated authority to his brigade commanders, yet his close attention to organizational and logistical minutiae sometimes drove Burnside to the point of exhaustion. Besides, he had a trusting nature, a quality that would hardly serve him well in the backbiting Army of the Potomac.

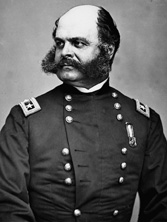

Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside (Library of Congress)

Frustrated by McClellan’s failure on the Virginia Peninsula, in July 1862 Lincoln had offered Burnside command of the Army of the Potomac. With much self-effacement Burnside had declined. After Lee had begun his invasion of Maryland in September, Lincoln repeated the offer, and the general had again refused. At Antietam Burnside had commanded the Ninth Corps, and its performance, especially the supposedly tardy crossing of the famous bridge on the southern part of the battlefield, had stirred controversy and damaged his reputation. The once cordial relationship with McClellan had cooled during September and October; Little Mac evidently had come to consider Burnside a potential rival.44

Burnside’s appointment to command the Army of the Potomac seemed logical enough. After all, in North Carolina he had shown promise directing a successful campaign. Though hardly a close student of strategy, Burnside was intelligent and hardworking. Even Chase, who clearly preferred Hooker, admitted that Burnside had “some excellent qualities” and believed that the administration would strongly support him. Stanton also favored Burnside, though Lincoln apparently did not consult the cabinet on the matter.45

Like McClellan, Burnside had been a Democrat before the war, but unlike his erstwhile friend, he had come to favor emancipation. Burnside had few political enemies; more significantly, he had few political friends. His selection aroused no partisan bickering, a plus for Lincoln, but Burnside himself had no political base of support should he run into trouble. As Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz has pointed out, a successful commander must understand politics and be able to deal with politicians, yet Burnside remained a political innocent. Where McClellan tended to espy numerous enemies near and far, Burnside could discern none, regardless of proximity.46

Contemporaries considered Burnside an impressive physical specimen. A six-footer with a large face and balding head, his bushy, brown sideburns curved around his lips into a full mustache. This luxuriant facial hair and his dark, deep-set eyes rendered his appearance distinctive and memorable. Burnside’s dress mirrored a frank, hearty simplicity. Careless about his uniform, he often rode about in a plain jacket and fatigue cap. Soldiers appreciated his informality, cheerfulness, and good humor.47 Burnside’s honest humility stood in striking contrast to the devious arrogance of McClellan or Hooker. Even the general’s detractors found him amiable and appealing.

In many ways Burnside was his own toughest critic, and genuine modesty was his worst failing. “I do not feel equal to it,” he confessed to Brig. Gen. Orlando Willcox the morning after taking command. In his first order to the army he expressed “diffidence” about his own ability. The enormity of this new assignment soon became a crushing burden. Through the prism of his own limitations, Burnside saw fearsome, almost insurmountable difficulties. He had trouble sleeping and kept telling anyone who would listen that he was not the man for the job.48

Lincoln, who well understood the need for self-confidence in politics, should have been wary of appointing a man who had repeatedly expressed sincere doubts about his own capabilities. Even Burnside realized that the entire country, from the president to the corn shucker, expected an immediate advance against the Confederates. In such a campaign, the general’s mistrust of his own abilities and a penchant for second-guessing himself could become fatal handicaps.

“Burnside, it is said, wept like a child, and is the most distressed man in the army, openly says he is not fit for the position,” Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade reported the day after McClellan’s removal. Even generals who were not charter members of the diehard McClellan faction wondered why they should have confidence in a commander who had so little confidence in himself.49 The rank and file shared the top leadership’s concern. Some soldiers insisted they would never have the same faith in Burnside they had in McClellan. Newspaper reports that Burnside would speedily crush the rebellion elicited howls of ridicule around campfires.50

At this point, however, such opinions hardly predominated, as the general’s easy manner and simple patriotism made him naturally popular. Whether the change was for the best or not, and despite suspicions that Burnside had conspired with Washington politicians to replace their hero, even ardent McClellan men grudgingly admired their new commander. Yet Burnside would have little time to prove himself, and rumors persisted that Hooker would soon take his place.51

More hopeful bluecoats forecast that Burnside’s victories would soon erase all memory of McClellan. The sturdy devotion of Burnside’s old Ninth Corps was reportedly inspiring the rest of the army.52 Many soldiers expressed confidence in his military skill. “He has been my man for the last eight months,” a New York officer informed his brother. Although they surely should have known better by this time, some sanguine veterans (and many new recruits) predicted the speedy defeat of the Rebels.53

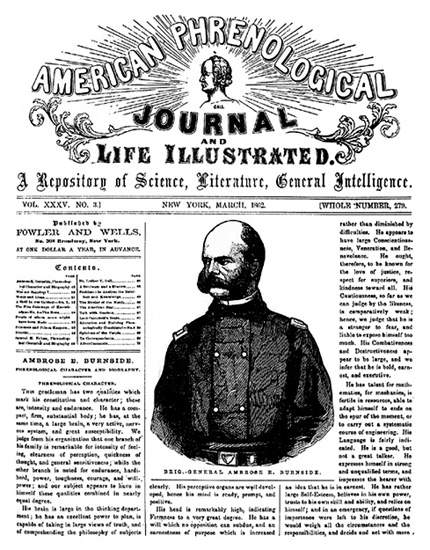

The northern public naturally took great interest in Burnside, and speculation about his abilities had already gone far afield. Throughout the war the American Phrenological Journal had regularly published profiles of leading northern generals. In the spring of 1862 during the North Carolina campaign an anonymous writer had offered a detailed phrenological analysis of the latest Union hero, Ambrose E. Burnside. His skull shape indicated a “large brain” and “very active nervous system.” The general displayed “clearness of perception,” “quickness of thought,” an “excellent power to plan,” and a “will which no opposition can subdue.” His “Cautiousness” seemed to be “comparatively weak” while his “Combativeness and Destructiveness appear to be large.” As if to confirm its ludicrousness, this phrenological reading had concluded that Burnside possessed “rather large Self-Esteem” and a firmness akin to that of Stonewall Jackson.54

Such pseudoscientific musings had undoubtedly convinced some readers and bemused others, but they clearly illustrate how deeply the war had reached into the recesses of American life. If phrenologists had indeed been paying attention to Burnside, then the war had become all consuming. It is significant that, like most other assessments of Burnside before Fredericksburg, even this one had been favorable.

Burnside profile, American Phrenological Journal, March 1862

Burnside’s appointment generated surprising enthusiasm among politicians. In November 1862 hardly anyone had anything bad to say about the general, at least publicly. For Democrats it was enough that he had long been McClellan’s friend (apparently reporters had not yet caught wind of their recent contretemps). Building on his predecessor’s masterful strategy, Burnside would soon march triumphantly toward the Rebel capital.55 In some ways Republican editors agreed, but they plainly expected a greater aggressiveness. “GOD SPEED GENERAL BURNSIDE!” Harper’s Weekly proclaimed. “March and fight” will replace “wait and dig,” a Philadelphia newspaper correspondent predicted. Most Republicans applauded the appointment, and Rhode Island governor William Sprague arranged a 100-gun salute to honor the state’s adopted son, who now commanded the largest field army in the world.56

Some radical Republicans, although they appreciated Burnside’s belated support for emancipation, worried that Lincoln’s choice reflected a lingering caution and debilitating conservatism. A New York Tribune reporter who had met Burnside considered him a man of distinctly limited ability; a Chicago Tribune editorial deplored efforts by some newspapers to turn the general into a second Napoleon. Working as his father’s secretary in London, young Henry Adams, the already world-weary skeptic, coldly commented, “I do not believe in Burnside’s genius.”57 At this point all opinions, however informed or groundless they might be, amounted to little more than speculation. Given the stakes involved and the consuming interest, rash predictions, unfounded expectations, and far-fetched rumors were inevitable.

Confederates also assessed the significance of McClellan’s departure and with equally mixed results. Southern generals had always been able to rely on McClellan’s lethargy, a Georgia editor noted with sly contempt and rare candor. Privately at least, the Confederate high command agreed. “We always understood each other so well,” General Lee remarked about McClellan. “I fear they may continue to make these changes till they find some one whom I don’t understand.” Such a statement suggested overconfidence, while southern newspapers tried to goad the deposed general into marching on Washington.58

The removal of McClellan, often described as the Yankees’ ablest general, boded well for southern fortunes, or so many Confederates believed.59 The southern press waxed enthusiastic. A desperate northern administration had not been able to abide having a Democratic general leading a heavily Democratic army; Lincoln and Seward would pay the political price.60 Reports from deserters and prisoners about demoralization in the Army of the Potomac made for cheerful reading. A Richmond newspaper claimed that Halleck had been forced to visit the Federal camps to quell the protests. “All Yankeedom is in an uproar,” a young Charleston woman gloated.61

As for the new Federal commander, he seemed beneath contempt. At the beginning of the war Burnside had been “little better than a loafer about Washington, having failed in everything he had undertaken,” the Richmond Daily Whig sniffed. Should the bluecoats be foolish enough to try an advance on Richmond so late in the year—and many Confederates wondered if they could—the weather would stop them dead in their muddy tracks. “Freezing nights and bogy roads are incompatible with the safe retreat of a beaten foe,” explained the Charleston Mercury. The Yankee government itself seemed to be tottering toward collapse.62

Despite the wildly exaggerated tone of many editorials, Confederates had good reason to rejoice as the end of the year approached. The northern elections, McClellan’s removal, reports of Yankee demoralization, and the appointment of an incompetent commander all had engendered a buoyant faith in southern prospects.

General Burnside, of course, was preparing to quash that faith. After officially assuming command on November 9, he established headquarters at the nearly deserted town of Warrenton, Virginia. Once a thriving village of more than 600 inhabitants, Warrenton, which boasted a respectable hotel, a few businesses, several churches, and some impressive private homes, had grown shabby under the press of war. Many stores were closed, and the sick and wounded of both armies crowded the streets. Coffins filled the Presbyterian church, while local women tended an already sizable Rebel cemetery on the edge of town. “Neglect and decay” could be seen “everywhere,” one Union staff officer remarked, and most of the locals stayed indoors.63

A little over a week after Burnside took command, some soldiers from the 133rd Pennsylvania tramped into Warrenton to buy soft bread, a long-sought-after luxury. They discovered a true seller’s market: high prices and an extremely doubtful product. Soon, however, livestock and poultry began to disappear from pens and coops. “We steal every thing we come across,” a hungry Michigan recruit bragged to his father.64

Yet the pickings were slim because John Pope’s army during the summer and retreating Confederates more recently had already stripped the area of provisions. Ninth Corps bivouacs near Warrenton with names such as “Hungry Hollow” and “Camp Starvation” accentuated the problem. Salt pork and sugarless coffee became staples as even the accursed hardtack grew scarce. Available food was often inedible. “The pork was so mean that we consigned it to the flames,” a Maine private observed ruefully.65 The army’s scattered divisions fared little better elsewhere in northern Virginia. Hardtack was low, supply wagons were late, and men were hungry. The story was the same at Waterloo, New Baltimore, White Sulphur Springs, and other places.66

Most of these supply problems were temporary, and the commissary wagons quickly caught up with the soldiers. But even as the men broke open the “cracker” boxes and Burnside tinkered with his campaign plans, the weather worsened. Snow fell at Warrenton on the day McClellan was removed, again on the day Burnside took command, and three days later on November 12. Already the bluecoats realized that a winter campaign with no shelter except fly tents would be deadly. With tongue only partly in cheek, a Michigan man in the First Corps teasingly informed his wife that he might not be able to undress and climb into bed immediately when he returned home but would have to sleep outdoors for the first couple of nights.67

In the wake of this exposure came sick lists, fatal fevers, and camp burials. Of the approximately 700 men in the 13th New Hampshire, some 200 had been hospitalized by mid-November. Medical treatment in the Army of the Potomac had improved since the summer, but there were still negligent or drunken surgeons absent from their posts. Helpless patients lying on foul beds “crawling with vermin” went unwashed for days. The wretched conditions spurred Dr. Mary Walker to supervise the transfer of the most seriously ill to Washington hospitals. Amid general neglect and growing indifference to death, one nurse asked, “Does war makes us worse than the heathen?”68

With a lull in the fighting and the air turning cold, the army might have gone into winter quarters. Understanding why McClellan had been removed, however, Burnside did not dare to consider that alternative.69 On the very day he took command, the general responded to Halleck’s insistent request for a campaign plan. After feints in the direction of Culpeper or Gordonsville, the Army of the Potomac would “rapidly move” toward Fredericksburg and from there advance on Richmond. The line of march would effectively shield Washington from Lee’s army—always a sensitive point with Lincoln and Stanton. Burnside laid out the advantages of this more direct route, with its short, defensible line of communications, but needlessly added that even if some Confederate forces headed north while Richmond was being captured, “the loss of a half a dozen of our towns and cities in the interior of Pennsylvania could well be afforded.” There is no evidence that anyone in the corridors of the War Department fussed over this curious passage, an indication perhaps of the administration’s willingness to accept almost any plan that promised to end the costly stalemate in the East. Burnside carefully listed his subsistence needs and requested that pontoons be sent for use in bridging the Rappahannock. He proposed dividing the Army of the Potomac into three wings but did not go into detail about organizational changes.70

Burnside had sounded a decisive note in his first important dispatch to the War Department. Whether he had spent enough time considering alternatives is doubtful. But the political pressures were inescapable, and a successful offensive demanded not only decisiveness but speed. Given the strategic objectives and need for an immediate advance, Burnside’s plan had considerable merit and some potential for success.71

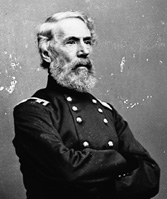

Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck (Library of Congress)

After receiving Burnside’s proposal, Halleck requested a meeting and on November 12 traveled to Warrenton with Herman Haupt and Quartermaster Gen. Montgomery Meigs. In some ways Halleck’s trip marked a departure from his usual passivity and avoidance of responsibility. Despite his reputation as a military scholar, “Old Brains” did not impress his contemporaries. He looked less like a general and more like an overly prosperous banker, with his bald forehead, double chin, and slight paunch. His blunt, almost clipped manner of speaking could not disguise a wariness of others and frequent hesitation to express his own views. As general in chief he hated making decisions and seldom provided the kind of clear, detailed advice Lincoln or the army commanders needed.72

Following a pleasant meal at a local hotel, Halleck, Meigs, Haupt, and Burnside settled down to business. The meeting, however, began on a sour, albeit familiar, note. Burnside still insisted that someone else should have been appointed to command the army. “I am not fit for it,” he repeated. Tired of such talk, Halleck impatiently asked for details of a plan that he already distrusted. Burnside obligingly explained the advantages of the Fredericksburg route, but Halleck urged sticking with the line of advance toward Culpeper and Gordonsville. Haupt, the railroad man, naturally preferred the shorter Fredericksburg route. After more discussion Halleck refused to issue any orders but agreed to present Burnside’s ideas to Lincoln. If the president approved, Burnside would march the army to Falmouth and cross the Rappahannock River on pontoon bridges. Halleck would arrange to have the pontoon trains moved to Falmouth.73

Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner (National Archives)

Burnside’s proposal to abandon the line of advance that the administration had pressed on McClellan did not please Lincoln, and he likely shared Halleck’s reservations about the Fredericksburg route. Yet the president hesitated to show any lack of confidence in his new commander, and so on the morning of November 14 Halleck wired Burnside the administration’s response: “The President has just assented to your plan. He thinks that it will succeed, if you move rapidly; otherwise not.”74 Burnside recognized the necessity for concentrating his forces and marching, but this curt and unenthusiastic response from Washington hinted at trouble ahead.

His plans approved, Burnside ordered the reorganization of the Army of the Potomac into three grand divisions, with the Eleventh Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel, as a reserve force.75 The Right Grand Division (Second and Ninth Corps) would be commanded by Maj. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner. At age sixty-five Sumner was the oldest corps commander in the army. Dubbed “Bull” because of his booming voice, bravery under fire, and an old army story about a musket ball that had once bounced off his thick head, Sumner had three notable characteristics: unwavering loyalty, limited ability, and precarious health.

Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin (National Archives)

Maj. Gen. William B. Franklin would command the Left Grand Division (First and Sixth Corps). Franklin had graduated at the top of the same West Point class (1843) in which Ulysses S. Grant had ranked twenty-first. The cautious Franklin was a McClellan loyalist of the first order, albeit a capable engineer and solid administrator. Throughout the coming campaign his lack of enthusiasm and initiative would border on insubordination.

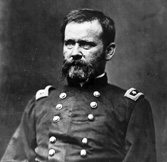

Hooker would lead the Center Grand Division (Third and Fifth Corps). Distasteful as it was to him, Burnside had to make the appointment. Hooker could not be ignored; he had the appropriate rank, powerful political connections, and undoubted abilities as a soldier. But in an army that he thought he should command (and with Republican editors continuing to puff him in fawning editorials), Joe Hooker would hardly be a model subordinate.76

Creating the grand divisions added another layer to the command structure, and either the corps or grand division commanders could easily become superfluous. Under this scheme Burnside would have less contact with the corps commanders and even less with the vitally important division commanders. The cavalry and artillery remained scattered among the grand divisions. Although Burnside greatly reduced the swollen adjutant general’s staff, the reorganization had ensured that communications and staff work would only become more complex and difficult. All these important changes also delayed the advance toward Fredericksburg.77

As the reorganization proceeded, the soldiers waited, complaining as usual and speculating about the future. “We are making history,” Col. Robert McAllister of the 11th New Jersey told his family. “The eyes of the world are upon us.” Even ardent McClellan men sounded a note of enthusiastic patriotism. “Love of country, especially such a country as ours where the blessings of a free government and the best of institutions are enjoyed alike by all, should be paramount to every other,” a New York staff officer believed. Soldiers broadly embraced the values of a middle-class democracy, and many tried to conform to its model of virtuous citizenship.78 Duty remained their polestar as they sat in their tents or around the campfires pondering what might happen over the next week or so.

Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker (National Archives)

Yet nervousness about Burnside, a lingering preference for Little Mac, and uncertainty about where the army might be headed also made soldiers uneasy. Men in the newer regiments and even some veterans might dream of reaching Richmond, but many still expected (or, rather, hoped) the army would soon go into winter quarters.79 Such thoughts partly reflected a crisis in confidence. Perhaps Confederate generals were superior, and maybe even their soldiers were braver. A Michigan recruit bitterly remarked that none of his comrades would ever see the Rebel capital except as prisoners of war. The new Congress would press for peace negotiations, a Massachusetts officer predicted, and if the enemy held out until spring, “the Confederacy is a fixed fact.”80

Whether stemming from a prickly personality, momentary pique, or genuine despair, such pessimistic statements probably no more reflected the army’s general opinion than did the wildly optimistic declarations. Yet some disillusionment with the whole enterprise was unmistakable. Pvt. Roland E. Bowen of the 15th Massachusetts badly wanted to come home but doubted his chances. “If I ever do,” he exploded to his wife, “I will see this Union in the bottom of Hell before I have any thing to do with another war.” A greatly frustrated Michigan captain wrote in his diary, “We are fooled, beaten, bamboozled, outflanked, hoodwinked & disgraced by half our numbers. . . . All the devils in Hell could not stand before this army if it were led & handled [by a capable commander].” A beautiful fall had already gone to waste: “Hell & furies it is enough to drive a man mad if he has one particle of regard for his country.” A chastened sadness and a Lincolnesque fatalism crept into soldiers’ letters and diaries. “If a ball takes off a limb, they must at least discharge me,” an orderly in Hancock’s division remarked. “If the ball touches my heart the Almighty will give my discharge nor stop to make it out in duplicate.”81

Worries about Confederate intentions compounded these fears. That sly old fox Lee might not even contest the crossing of the Rappahannock and instead adopt a Fabian policy of luring the Army of the Potomac away from its supply base. Of course, any rumors involving a movement by Jackson, who was seen by many northerners as nearly invincible, made folks edgy.82

“The war languishes. We are slowly invading Virginia, but there is nothing decisive or vigorous done there or elsewhere,” George Templeton Strong noted glumly. But he had a “foreboding,” a sense that this lull in the war was about to end and there was about to begin a “terrible, crushing, personal calamity to every one of us; when there shall be no more long trains of carriages all along Fifth Avenue bound for Central Park, when the wives and daughters of contractors shall cease to crowd Stewart’s and Tiffany’s, and when I shall put no burgundy on my supper table.... ‘Without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sins.’ It is impossible this great struggle can pass without our feeling it more than we have yet felt it.” Few civilians engaged in such morose ruminations. Screaming headlines began appearing in the newspapers again as editors seated behind great desks in comfortable chairs composed editorials clamoring for a rapid advance toward the Rebel capital. Burnside would be the man; the end of the war was now in sight; steadfast veterans would push on to victory.83 Brave young men in blue had only to march toward the Rappahannock.