4 Marching

I have destroyed the enemy merely by marches.

—Napoleon I

Herman Haupt, single-minded in pouring his considerable talent and energy into moving military supplies quickly over the railroads, always seemed to encounter snags. Washington red tape and generals who made impossible demands were bad enough, but what really irritated the impatient Pennsylvanian were delays. He wanted his trains to move—constantly. “Trains must not stand still, except when loading and unloading,” he told Burnside, “and the time for this should be measured by minutes, not by hours.” Manassas Junction was the main bottleneck, and the irascible Haupt upbraided Brig. Gen. Daniel E. Sickles when he discovered that the general’s “agent” there had reportedly diverted engines to make unloading cars more convenient for his troops.

Haupt’s men, too, were often tactless and sometimes profane; but shipping supplies along a single-track railroad was no easy task, and Haupt refused to let a mere general or even the secretary of war stand in his way. When Stanton ordered officers to cooperate in unloading the trains and then tried to require railroad workers to provide receipts for all supplies, Haupt refused. This prompted one of Stanton’s famous rages, but he nevertheless gave up on having the order enforced.1

Haupt still had his hands full. Anticipating a change in the Army of the Potomac’s supply base, Haupt had argued for rebuilding the stretch of the Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad between Aquia Creek and Falmouth. This would allow supplies to be moved down the Potomac to Aquia Creek and on by rail to camps north of Fredericksburg.

As early as mid-October Haupt had brought the necessary lumber and other materiel to Washington. A month later, transports and troops were already on their way to Aquia Creek, and Haupt, along with a retinue of other officers, was busy inspecting wharves and partially destroyed track at Aquia Creek. After four days of work, by November 22 Haupt’s industrious engineers had rebuilt 800 feet of wharf and landed one engine. After two more days a bridge over Potomac Creek was in operation; two days after that the first engine was chugging toward Falmouth.

Haupt’s achievement had been impressive. The span over Potomac Creek stood nearly four stories high and had required more than 40,000 cubic yards of timber. Railroad cars loaded with supplies were placed on huge Schuylkill barges (two parallel barges bolted together) and floated down to Aquia Creek. From there they could be hooked onto engines and taken to Falmouth. Soon twenty trains a day ran over the repaired tracks. Shipments from Alexandria reached Falmouth within seventeen hours, including time for unloading and loading at Aquia. Of course, problems persisted. Unnecessary items got shipped, enterprising boys snuck onto trains hoping to sell their newspapers in the camps, and “contraband goods” being sent by “Jews, sutlers and others” sometimes evaded Haupt’s sharp lookout. Worse, shivering soldiers routinely stole wood intended for stoking the engines or would wash clothes upstream from water stations, so that “soap and other impurities” clogged the trains’ boilers.2

Haupt already knew what Burnside and other generals were learning: the railroad was transforming military strategy. To one engineer the newly rebuilt wharves at Aquia seemed as “busy as I ever saw the docks of new york in her palmiest dayes.”3 Watching the trains leave for Falmouth, an observer could easily see how dependent the army had become on this marvel of the age. Railroads determined lines of march and sometimes dictated campaign strategy.

Troops moved great distances by rail, but wagons, horses, and mules remained the backbone of military transportation. Soldiers marched to battle-fields accompanied by cavalry, artillery, and supply trains. A four-horse team could haul 2,800 pounds of supplies along good roads but considerably less on a rough country lane, especially after a rain. An army used up horse-flesh. The Federals generally had enough horses, though even before Burnside took command, disease had hobbled many animals. A Wisconsin chaplain succinctly described the problem: “The heel becomes very sore and the hoof separates from the skin so that when they [the horses] step, it opens, splits, and cracks.” No one seemed to know what caused the malady, though a Pennsylvanian speculated that perhaps the animals had been eating too much corn and not enough hay. Some cattle and horses also suffered from a usually fatal “black tongue” disease.4

Aquia Creek and Fredericksburg Railroad, construction crew at work (National Archives)

These problems threatened to slow Burnside’s movement before it had even begun. In various artillery batteries, anywhere from one-third to one-half of the horses were useless, and raids on local farmers alleviated only part of the deficit.5 Cavalry officers blamed wet weather, poor forage, and hard riding for worsening the problem, but some regiments just took better care of their animals. Whatever the causes, the horses suffered, stumbling on hooves that seemed ready to fall off, “blood and matter squirting out all around the foot,” according to one trooper. Quartermaster General Meigs informed Burnside that it might not be possible to provide enough healthy horses for both the supply trains and the cavalry.6

Federal cavalry was already advancing toward the Rappahannock before the army itself began moving. Especially nervous about Jackson’s where-abouts, Union troopers tried to keep tabs on Lee’s army. Sharp skirmishing with Confederate cavalry occasioned some loss of baggage and supplies but few casualties. Burnside feinted with cavalry and detached infantry toward White Sulphur Springs in hopes of making Lee think he still intended to advance on Culpeper along the Orange and Alexandria Railroad. Later, as the army began its march to Fredericksburg, Federal cavalry continued to monitor Rebel movements, especially along the Rappahannock fords.7

Aquia Creek Landing, Virginia, wharf, boat, and supplies (Library of Congress)

With the railroad to Falmouth still under repair and without making sure the greatly needed pontoons had left Washington, Burnside ordered his army forward. At 5:00 A.M. on November 15, Sumner’s Right Grand Division began leaving Warrenton; by late morning most of his men were on the road heading southeast.8 Marching four abreast and carrying between forty and fifty pounds of equipment per man, the soldiers could go about two and a half miles an hour, but delays were common, especially in early morning when the men ate hurried breakfasts and tried to repack the tents. Soldiers would often have to leave the road to let artillery or supply wagons pass; some regiments trudged through nearby fields on parallel routes. Clause-witz noted that a modern army “was accustomed to consider a fifteen-mile march a day’s work,” and Sumner’s troops matched this standard.9 The advance regiments covered the forty miles to Falmouth in around two and half days, arriving on November 17. Compared with McClellan’s more leisurely pace or to any reasonable expectation, for that matter, Burnside had moved quickly.10

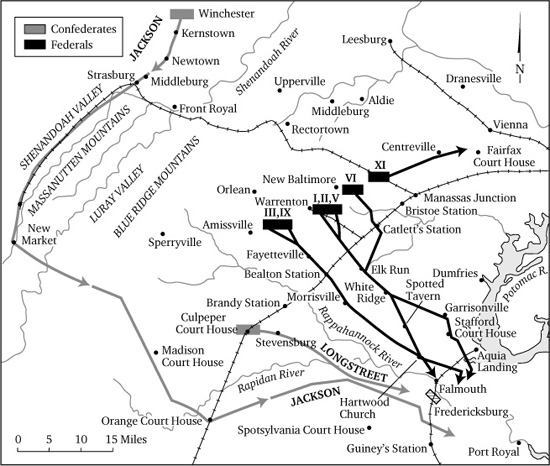

March to Fredericksburg

Yet even as the first of Sumner’s men neared Falmouth, rain began to slow the march, and all along the route soldiers in the trailing regiments noticed shoes stuck in the mud. Men were soon using rails to pry artillery pieces out of the muck. “Wet and disagreeable,” a mud-spattered Massachusetts corporal in the Irish Brigade tersely noted.11 The new regiments quickly lost their illusions about the glories of field service and inevitably straggled, littering the roadside with surplus baggage.

Inexperienced officers working with poor maps added to these woes by making wrong turns, getting lost, and then doubling back. After a roundabout and arduous journey through the countryside, a veteran in Brig. Gen. Oliver Otis Howard’s division noted how his comrades exercised the soldiers’ sovereign right to complain: “Oh what deep and heartfelt curses did I repeatedly hear heaped upon the generals, the war, the country, the rebels, and everything else.”12

Pvt. Joseph E. Hodgkins of the 19th Massachusetts thought he had as much to gripe about as anyone. His regiment had marched about forty miles in three days, sometimes in the rain (or perhaps snow, as the regimental history later claimed). During the night of November 18 Hodgkins “laid across two or three corn hills” and slept fitfully. On guard duty two days later he had gotten “pretty well soaked” and finally flopped down in a sopping blanket, “wet to the skin.” His experience was typical. Campaigning in such weather struck many as ludicrous; it seemed cold enough for snow. Men awoke to find an inch or two of water running through their shelter tents. And sometimes they had to light damp wood with flint and steel because they had no matches.13

Besides being cold and wet, soldiers were usually hungry. The supply trains were mired in mud or for some other reason had not caught up with the infantry. A New York regiment had ten “crackers,” coffee, and a little fresh meat for the daily marching ration, but a New Hampshire outfit had to endure an entire day without water. The fortunate might snare a rabbit along the way, while the more enterprising (or ravenous) might stumble through the dark, ford creeks, and fall into muddy ditches searching for the commissary wagons. Officers with more compassion than discretion doled out a few tablespoons of whiskey to their sullen men, but the tipplers would soon quaff their portion and then beg, buy, or steal the precious elixir from the teetotalers. The ensuing fights, black eyes, bloody noses, and hangovers hardly improved morale.14

Short rations, long days, general exposure, and a few unexpected annoyances soon took their toll. Some Buckeye soldiers making their way to Falmouth through a pine forest faced an onslaught of wood ticks. These pesky creatures clung to legs, necks, and heads, and their bites caused unbearable itching for several days. More generally, men already weakened by maladies such as diarrhea and typhoid fever merely grew sicker from the added exertion. Older recruits fell victim to neuralgia and rheumatism from sleeping on cold, damp ground. But the youngest soldiers also suffered. A nineteen-year-old in the 21st Connecticut, after keeping up with his regiment for several days, collapsed from exhaustion at the end of the march and awoke with his legs in water. Feverish and delirious, he was taken to a field hospital. In and out of consciousness and even hallucinating that his mother had arrived to see him, he soon died. After several other men suffered a similar fate, soldiers christened the place “Camp Death.”15

But for all the misery, the appearance of the advancing Federals remained impressive. There was something grand about so many soldiers tramping along the roads, through woods, and across fields. The men would naturally complain of the cold, the mud, and the food, but the marching itself made them exuberant. A New Yorker captured the scene: “It is a splendid sight. There is something majestic and grand in the march of so large an army.” With their long lines of troops and hundreds of campfires glowing in the night, the vast legions appeared irresistible. Standing at her cabin door eyeing the passing spectacle, an awestruck woman agreed: “Dear suz! I didn’t s’pose there wuz so many folkses in the world.”16

The coming campaign would surely test whatever enthusiasm the Federal soldiers could muster. “Almost anyone can be a soldier in summer,” Capt. Charles Haydon commented both soberly and self-assuredly, “but to have served faithfully one’s country in the winter of the year & of its hopes will be a lasting source of pride & gratification.” Hard fighting now seemed likely, but a Vermont corporal predicted that the Federals would cut off Lee from Richmond and starve his army.17

Such optimism, however, had little tangible basis. What did most of the enlisted men, or their officers for that matter, really know of Burnside’s plans? With the weather turning colder, they could only pray that their new commander would proceed quickly and decisively. Some soldiers, still smarting from the removal of their idol McClellan, claimed to prefer the old James River route to Richmond or simply wished the army would settle into winter quarters. Others, again under the lingering McClellan influence perhaps, fretted about going into battle against supposedly much larger Confederate forces. Marching could, after all, produce as much despair as exhilaration. The patrician Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. had seen the worst fighting of the war so far at Antietam, and as he traveled over the “muddy & cut up roads” of northern Virginia, he concluded that “we never shall lick ’em.” With the cynicism of a combat veteran and the cocksureness of a Brahmin intellectual, he declared the subjugation of the Rebel states an impossible task.18

Behind Sumner’s forces the rest of the army was also advancing toward Falmouth. Despite some grumbling about laboring on the Sabbath, on November 16 the First and Sixth Corps left their camps around Warrenton and New Baltimore. As a McClellan protégé, Franklin naturally hoped to move “without fatiguing the men too much.” Regardless of bad roads, some wrong turns, and a few broken-down wagons, by November 18 the first regiments of the Left Grand Division had reached Stafford Court House.19

It had rained most of the way. The diaries, letters, and regimental histories often mentioned rain only in passing, and it is tempting for historians to do the same. Yet the foul weather did more than bog down artillery, soak uniforms, or saturate blankets. The rain dampened spirits and marked an ominous beginning to an important campaign. As the soldiers noted their slow progress, morale sank almost as quickly as a caisson in the mud. Slippery climbs up treacherous hills wore the men out physically but also drained their psychological reserves. After a day in a cold, driving rain a Wisconsin officer wrote home from his “BIVOUAC IN THE BRUSH TEN MILES FROM ANYWHERE, IN STAFFORD CO., VA.” One meticulous member of the 13th Massachusetts measured the mud on November 20; it was two inches deep. The next day it was three inches, and after a two-day halt five inches of ooze all the way to the commissary wagon.20

Soldiers naturally dwelled on their immediate miseries. Mule drivers exhausted their profane vocabularies as did infantrymen who had lost their shoes and slogged along in their stocking feet. With forgivable exaggeration a Massachusetts soldier claimed that the “amount of muscular energy required to lift your feet with ten pounds or more of mud clinging to each foot, can hardly be appreciated except by persons who have a knowledge of the sacred soil of Virginia.”21

As Sumner and Franklin advanced toward the Rappahannock, Hooker’s Center Grand Division became the rear guard. On the morning of November 17 the Fifth Corps set out for Warrenton Junction while the Third Corps headed toward Bealeton. Both corps eventually converged on the area around Hartwood Church and then turned east to cross the road between Stafford Court House and Falmouth near Potomac Creek. Perhaps hoping to win over a troublesome subordinate, Burnside commended Hooker “for carrying out so successfully the most difficult part of the late movement—bringing up the rear.”22

This reference to “bringing up the rear” could just as easily have rankled the egotistical Hooker, but his assignment had hardly been easy. Given the complexity of the routes and the condition of the roads, many regiments alternately marched or waited in rain-soaked camps for nearly a week. The men in Brig. Gen. George Sykes’s division dubbed their soggy bivouac near Hartwood Church “Camp Misery.”23

Pvt. Howard Helman, a seventeen-year-old printer who had enlisted in the 131st Pennsylvania only three months earlier, left a careful record of the trek from a foot soldier’s perspective. On November 17 Helman’s feet were quite sore from marching at what he considered a rapid pace in a steady drizzle. The second day was even worse because his regiment was supposed to keep up with the supply train and rescue stuck wagons. It rained the next day, and the exhausted Helman had to sit up most of the night because of “rheumatism” and a “severe pain across the lungs.” On November 20 and 21 the men stayed in camp but were nearly out of food. The following day they headed out again. The “roads kept getting worse” and they had nothing to eat, but somehow they made it to a “nice piece of ground” near Potomac Creek.24

Because their march began later and lasted longer, Hooker’s troops bore the brunt of the inclement weather. Stories about pouring water out of boots and scores of dead horses and mules left lying along the army’s track may have been embroidered, but rain and wind made setting up camp at the end of a long day nearly impossible. Any logical stopping place had typically become a sea of mud. Tent pegs would not hold, and the canvas blew all over. Tents that did stay up had rivulets of water running underneath, soaking blankets and other gear. Fires started with damp wood sputtered out in the drizzle. A disgusted member of 133rd Pennsylvania, sounding rather like the biblical prodigal son, announced he would now gladly pay five dollars for the privilege of sleeping in “his father’s hog pen.”25

At the end of a dreary day the Virginia countryside appeared all that more desolate. Words such as “miserable,” “tumble down,” and “forlorn” described the land and its people. Dilapidated farms, many now deserted, with overgrown fields dotted the landscape. “Old cleared ground and a cow is the wealth of the farmers,” Col. Robert McAllister of the 11th New Jersey noted sadly. “Children don’t wash at all.”26

Empathy for Rebels, however, no matter how forlorn their appearance, was in short supply. The New England troops in particular expressed condescension, at best, and contempt, at worst, toward the poor Virginians, a downtrodden people who had failed to absorb the Yankee virtues of thrift and learning. The change in attitude—already noticeable during McClellan’s final days—became even more pronounced during and after the march toward Fredericksburg. Speaking for many of his comrades, a Rhode Island artilleryman declared, “We dont think it any sin to take what we want to eat from secesh.” What a New York surgeon called “stolen luxuries” satisfied hunger but, more importantly, afforded “revenge[, a] sweet morsel [that]... rolled with pleasure under the tongue.” The reduction of Virginia to a vast wasteland might simply be an inevitable consequence of civil war. After a beautiful young woman begged some New Hampshire soldiers not to steal the hay from her family’s barn, they found it “rather tough to withstand her tears” but went about their plundering. Hardened to such pleas, these same men had just the day before burned down a “secesh” barn.27

Foraging became a great game, born of necessity, the soldiers would have stoutly maintained, but also affording spiteful amusement. Nor did cleaning out Confederate larders mean distinguishing between wealthy disunionists and more humble yeomen. Hungry Federals bolted down pork and beef that tasted all the sweeter for having been stolen from their enemies, rich or poor.28

The moral dilemma of feasting on other folks’ misery now received humorous treatment. Stomachs full at last, the men relaxed around camp-fires recounting hairbreadth escapes from irate, shotgun-wielding farmers. “There is one thing certain the people will not be troubled feeding chickens this winter,” a newly enlisted chaplain chortled. Capt. Frank Sterling of the 121st Pennsylvania eagerly shared with his sister what he undoubtedly considered a clever analysis of the moral problem: “Quite a number of times fine pieces of pork, mutton etc. have come into my possession whose previous history I do not think it would have been safe to have followed up too closely. Under such circumstances I always follow [the apostle] Paul’s advice namely eat what is set before me without asking questions.”29

Much to the dismay of conservative officers, this new toleration, indeed relish, for plundering civilians was spreading. A member of the 79th New York sadly informed his mother that soldiers from Ohio, Michigan, and Indiana bragged about their depredations. Already frustrated over trying to maintain discipline in his division, General Hancock exploded when he discovered that even the chaplain in the Irish Brigade had been filching turnips.30 Some commanders still posted guards to prevent men from sneaking off to raid chicken coops or pigpens, and occasionally punishment was meted out for unauthorized foraging. In one of the Pennsylvania reserve regiments an hourly roll call prevented the men from scouring the countryside for fresh delicacies.31 Such strict measures, however, were rare. More often than not even high-ranking officers simply looked the other way. Be it honey or fresh mutton, the officers enjoyed their share of the spoils.32

Growing impatience in Washington and elsewhere for an offensive campaign left little time or energy for safeguarding Rebel property. The Army of the Potomac’s rapid march in the cold and rain reflected this new sense of urgency, yet the men themselves remained confused about what it meant. Soldiers had been sharply critical of the logistical failures, though many still declared themselves well pleased with Burnside and his aggressive strategy. “The knapsacks weighed like lead & the mud pulled like wax, & the rain came down in torrents,” a Pennsylvania sergeant in Hooker’s grand division observed melodramatically, “but we are going towards Richmond so we don’t care for all they are able to put on us.” To such determined souls the Confederate capital suddenly appeared within reach, and though that chimera had bedazzled volunteers before, the most hopeful new recruits even saw the end of the war in sight.33

All the same, many soldiers greatly resented pressure from the newspapers and politicians. With his usual acerbity General Meade complained that “it is most trying to read the balderdash in the public journals about being in Richmond in ten days.” Still convinced that the James River was the only practical route to the Confederate capital, Meade wondered why officials in Washington, especially Halleck, did not understand this. Men who had struggled through the rain and mud could only wish that those editors who so loudly demanded a winter campaign could have accompanied the army on its recent march.34

The first sketchy newspaper comments on the army’s advance toward Fredericksburg appeared on November 18, the day after Sumner’s men reached Falmouth. The familiar “On to Richmond” headlines and optimistic editorials blanketed the Republican press. McClellan partisans complained that the Army of the Potomac would at last receive all the troops and support necessary for conducting an offensive campaign—as if they had not before—and they even insisted that Burnside was resisting pressure from Halleck to move forward too quickly. Few newspapers had anything but praise for the new commander or his campaign plans, and the more confident editors fore-saw the Confederates falling back to defend their capital. “Hard fighting” lay ahead, the always sanguine Philadelphia Inquirer admitted, but “Richmond will soon be ours.” Having thrown off the incubus of “McClellanism,” the Army of the Potomac was showing unaccustomed energy and spunk.35

To skeptics, all of this sounded ominously familiar, but wishful thinking, nagging impatience, and political desperation clouded judgment. The logic of events seemed simple enough: McClellan had been removed for being too slow, and Burnside had moved forward quickly. The newspapers were already building up unreasonable expectations for the approaching campaign, and ironically enough every editorial praising Burnside only put more pressure on him, his generals, and his troops. Even enthusiastic support could hardly build confidence in a man prone to doubting his ability and second-guessing his own decisions. Nor could the insistent demands of a restless public revitalize an army still plagued by factionalism and whose apparently growing devotion to its new commander had yet to be seriously tested.

* * *

If the northern people oscillated between utter despondency and naive faith, public opinion in the Confederacy seemed more sanguine, equally contradictory, for sure, but much less mercurial. “The history of mankind cannot afford a parallel with the wonderful energies displayed and brilliant triumphs achieved by these Confederate States,” Governor John Gill Shorter informed the Alabama legislature. Even Zebulon Vance, the recently elected governor of North Carolina and no ardent Confederate nationalist, believed that as the “ephemeral patriotism” and “the tinsel enthusiasm of novelty” were disappearing, the people would soon have to display a “stern and determined devotion to our cause which alone can sustain a revolution.” According to Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws, the Yankees “acknowledge our superiority of courage and spirit.” Fighting for self-government just as their revolutionary forebears had done and proudly assuming the mantle of “rebels,” many Confederate soldiers now looked toward victory.36

To complement an often unjustified confidence, Confederates tended not only to denigrate but underestimate the enemy. If the southern cause stood for the spirit of 1776 and political purification, the northern government embodied all the evils of political consolidation and military despotism. Confederates expressed as much contempt as hatred for the Federals by repeatedly emphasizing supposedly fatal flaws in the Yankee character. A series of editorials in the Richmond Daily Whig—hardly a fire-eater sheet—expressed widely held beliefs. Not only did the Federals fight for an unjust cause (“the advantage of moral force is all on our side”), but they had evolved into “the vilest race on the face of the earth.” Their wickedness was nearly unfathomable: “besotted and intolerant, rapacious and stingy, fraudulent and roguish, boastful and cowardly, contentious and vulgar, envious and spiteful.”37

Faith in the purity of the cause and the wickedness of the enemy easily turned into self-righteousness. Pious Confederates saw themselves as crusaders against Yankee infidels; battlefield victories became signs of divine favor. As one Richmond editor fervently asserted, the “just God . . . who had baffled the devices of our enemies, will continue to aid us in our struggle for independence of the most corrupt and wicked despotism of modern times.”38 Of course many ministers and other Bible-believing folk doubted that God would simply punish the heathen Yankees without using the scourge of war to chastise the Confederacy’s perhaps chosen but often backsliding people.

Many citizens had apparently grown weary of self-sacrifice and were taking advantage of others’ suffering. “Speculators” and “extortioners” were widely condemned for driving up prices and impoverishing the people. These harpies, one soldier warned, “are stabbing the very vitals of the republic.” Petitions to governors and letters to newspapers complained of merchants hording scarce supplies until they rotted rather than selling them to poor families at reasonable prices.39

In such a cruel and selfish world, perhaps it was up to the female population to hold the people to a higher standard of morality. Given the “patriotic and intense feeling” of so many women, Governor Francis Pickens of South Carolina maintained, “no men who have such mothers, such wives, and such sisters, were ever born to be enslaved.” On November 14, the day Lincoln had given his grudging approval to Burnside’s change of base, a letter from a “lady” appeared in the Richmond Daily Enquirer urging the women of the Confederacy (with their “female domestics”) to join together at noon on December 1 to pray for peace and the success of southern arms, a call that echoed across the South.40

The fires of southern patriotism still burned brightly. And lest the Yankees (or fainthearted southerners) decide that the Confederacy could be starved into surrender, the Richmond Daily Examiner set them straight: “The sufferings of our people, poverty at our firesides, and the rags of our armies, instead of being hailed as signs of submission, should strike the North pale with despair. They are proofs of heroic resolution; they are endured without complaint; they are sacrifices to liberty in which we glory.”41

Yet the hardships faced by southern families could hardly be relieved by patriotic editorials. The government’s fiscal difficulties remained serious, and people showed little stomach for tough medicine. Even editors who railed against wartime opportunism drew back from price controls or other measures that interfered with free markets. “Prices must always be regulated by... supply and demand,” Jefferson Davis intoned, and for the government to meddle with ordinary commerce would only undermine public confidence.42

Davis had never been a bold politician or an original thinker, but in November 1862 his caution seemed justified. He had already expended much political capital pushing for conscription and the suspension of habeas corpus, and even with the war going fairly well, critics multiplied. Richmond buzzed with rumors that the president acted as his own secretary of war, interfered with his generals, and insulated himself from ordinary citizens. The cabinet, according to the Richmond Daily Examiner, presented a “living satire on the statesmanship of the South and the intelligence of the country.”43 Ironically, growing confidence in southern arms made carping seem less dangerous while simultaneously discouraging the adoption of policies that would have demanded greater sacrifices from ordinary citizens.

The recently appointed secretary of war, James A. Seddon, faced a familiar problem: the army’s ever growing demand for soldiers. Near the end of November the War Department summoned absent officers back to their commands on pain of losing their commissions and threatened absent enlisted men with being treated as deserters. The necessity for vigorous enforcement of the conscription laws became obvious as Federal armies prepared for offensive operations late in the year.44

Confederate president Jefferson Davis (Library of Congress)

Unfortunately for the Davis administration, some governors and editors still considered the draft a violation of both individual liberties and states’ rights. Yet the early flood of enthusiastic volunteers had long since slowed to a trickle. On the day that Burnside reorganized the Army of the Potomac into grand divisions, thirteen advertisements for Confederate substitutes appeared in the Richmond Daily Dispatch. A member of the 21st Virginia asked his father for help in procuring a substitute because even if it cost $1,000, he could earn more than that in a year working at home.45

Political backbiting and efforts to avoid conscription, however, did not signify general demoralization. Public confidence in Lee remained high even among the government’s harshest critics. Lee would look for an offensive opening and knew that giving up more territory would only add to the suffering of his beloved and already war-ravaged Virginia.46 With Jackson still in the Shenandoah Valley, the Army of Northern Virginia remained divided, but Lee showed little concern and would not reunite his forces until Burnside tipped his hand.

Much would depend on the Federals’ line of march and on accurate intelligence about their movements. Lee’s seemingly invincible cavalry chief, the dashing Stuart, had become the toast of Richmond and a magnet for attractive women (despite his deeply religious, abstentious, and somewhat prudish character).47 Stuart would serve as the army’s eyes and ears; but his men badly needed more carbines, and some three-fourths of their horses suffered from the same tongue and hoof ailments that were hobbling the Federal cavalry. The War Department promised to buy a thousand horses in Texas, but when they might arrive was anybody’s guess.48

As Stuart’s cavalry prowled the countryside, Lee advised Jackson to be ready to march should Burnside head toward Fredericksburg or cross the Rappahannock at some other point. Lee had not worried that Burnside might steal a march on him and trusted Jackson’s judgment on the timing of any move to rejoin the main body of the army in Culpeper. To impede the enemy advance, Lee had ordered the railroad between Aquia Creek and Fredericksburg destroyed along with the bridges and culverts, but both he and Davis were reluctant to have the tracks south of the Rappahannock torn up until it was absolutely necessary.49

On November 15 the Richmond Daily Enquirer reported the enemy advancing toward Fredericksburg. That same day Lee, unsure about either the direction or the timing of Union movements, sent an infantry regiment and an artillery battery to strengthen a small force stationed there. If Burnside’s troops had already crossed the Rappahannock and occupied the town, Lee would withdraw his forces to the North Anna River. Anticipating that Fredericksburg could not be held, the War Department and the president reluctantly authorized the destruction of the railroad between Fredericksburg and Hanover Junction. Lee remained uncertain about Burnside’s intentions because he had not yet received intelligence that the bluecoats were rebuilding the wharves at Aquia Creek. As Sumner’s troops approached Falmouth on November 17, Lee still thought it likely that Burnside would transfer his army south of the James River.50

Timing remained critical. So far Burnside had moved rapidly without Lee discovering his intentions. Learning that Sumner’s men were approaching Falmouth, on November 17 Lee ordered two of Longstreet’s divisions commanded by McLaws and Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom Jr. to head immediately toward Fredericksburg. As these units left their camps the next morning, some of Stuart’s cavalry splashed across the Rappahannock to scout out enemy movements and arrived at Warrenton just as the last Federals were leaving. At this point Lee could not be certain that the rest of Burnside’s army was following Sumner and still preferred to assume a strong defensive position along the North Anna River. There he could take advantage of the Federals’ elongated line of communications and launch a counterattack. Two days later Lee better understood the Federal movements and telegraphed Davis: “I think burnside is concentrating his whole army opposite Fredericksburg.” Given Lee’s apparent calm, Richmond officials simply assumed that the Army of Northern Virginia could stop Burnside.51

On November 18, in the midst of all-day rain, McLaws’s men left Culpeper Courthouse and headed toward the Rapidan River on treacherous roads. Preparing to cross the river at Raccoon Ford, some soldiers took off their shoes and socks before wading into the icy, knee-deep waters. “Men yelled, cursed, and laughed,” the brigade historian recalled. Others kept their shoes on rather than risk having their feet cut by rocks in the riverbed. One embarrassed recruit who had removed most of his clothes had to promenade without pants past a house full of curious ladies. The soldiers trudged through rain again the next day and reached Fredericksburg around noon on the twentieth.52

Ransom’s Division marched more slowly, completing the trek two days later. Wet, hungry, and miserable, these soldiers (many of whom were barefoot) were every bit as disconsolate as their Yankee counterparts.53 The artillery had an even harder time because the men had to strain as much as the horses to pry up gun wheels out of the mud. “A more drenched and disgusted set was never seen,” a member of the famous Washington Artillery recalled. To compound the misery, a hard-hearted surgeon refused to dole out a whiskey ration to the shivering men.54

By November 23 Longstreet’s other three divisions (commanded by major generals Richard H. Anderson, George E. Pickett, and John B. Hood) had reached the Fredericksburg vicinity. Lee had intended to send these divisions back toward the North Anna River, but when Burnside made no move to cross the Rappahannock, he ordered them to join McLaws and Ransom. Their more circuitous route afforded the men an even more protracted dose of discomfort. Shoe top–deep mud in some places caused considerable straggling. After marching several days in the rain, the men lay stiff and sore in their makeshift camps. Nearly 40,000 Confederate soldiers bivouacked in and around Fredericksburg, but Lee had still not decided whether to fight there or retreat to the North Anna.55

“If the enemy attempt to cross the [Rappahannock] river, I shall resist it, though the ground is favorable for him,” Lee informed the War Department as the last of Longstreet’s troops were arriving. Lee’s tone perhaps betrayed his annoyance with the government’s insistence that he not pull back. But the men in the ranks were not troubled. All along they kept telling their home folks of the “big fight” brewing.56 The mere appearance of Marse Robert in the camps near Fredericksburg inspired confidence. “Feel better satisfied in going into a fight under him than anyone else,” a South Carolinian chirped, giving voice to a near-universal sentiment in the Army of Northern Virginia. Burnside’s momentary advantage of surprise was gone. Once again Lee’s soldiers blocked the road to Richmond. Surveying some excellent defensive positions in the hills behind Fredericksburg, Brig. Gen. Thomas R. R. Cobb bragged that his brigade alone could “whip ten thousand of them attacking us in front.” Hearing enemy drums and bands playing across the river, the pious Georgian was itching for a fight, trusting in protection from a “Righteous God.”57

Civilians echoed this optimism. Should Burnside’s army be decisively beaten at Fredericksburg, Edmund Ruffin predicted, a northern peace party would end the war in two months, and without European intervention. Some observers still doubted that a major offensive would be launched so late in the year, but should the Federals attack Fredericksburg, the Richmond Daily Examiner assured its readers, the result could only be a “disaster” for Union arms. And Burnside? He “will enter the Hades of lost reputations,” the Richmond Daily Dispatch predicted.58

The next weeks or even days might change the entire course of the war. With armies in motion, even the Federals sounded more cheerful. For the troops, marching itself, despite all its hardships, often had a salubrious effect on morale. For sure, the temporary discomfort and supply problems produced plenty of grumbling and also sowed seeds of skepticism about the campaign, but the dissipation of the torpor and lethargy caused by the lull in the fighting since Antietam had been almost palpable. Burnside believed that he must strike quickly, and Lee, caught a bit off guard at first, stood ready to counter any thrust toward Richmond. The Federals hoped for a dramatic victory, though the lingering effects of McClellanism and nagging doubts about Burnside’s ability dampened enthusiasm. The Confederates faced growing logistical problems and no little internal dissension, but from General Lee to the humblest private, they exuded confidence.