10 Crossing

And crimson-dyed was the river’s flood, For the foe had crossed from the other side, That day, in the face of a murderous fire That swept them down in its terrible ire; And their life-blood went to color the tide.

—Nathaniel Graham

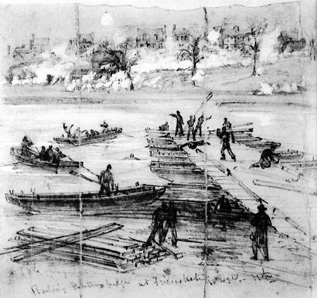

The bridge building began early in the morning of December 11, with the temperature in the mid-twenties, skim ice clinging to the riverbanks, and everything cloaked in a dense, stubbornly persistent fog. The job at hand required both skill and time. Wagons drawn by six mules bore the pontoons to the river. One group of engineers placed a heavy timber abutment on the ground and secured it with stakes; then a six-man team maneuvered a boat into place, turning it parallel to the shore and anchoring it in position. At this point several balks (floor timbers measuring twenty-five feet long and a little more than four inches wide) were laid over the first boat, “lashed” into place, and then topped with chesses (boards approximately fourteen feet long and twelve inches wide) laid across them. Side rails laid along the chesses over the outside balks completed the job. Another pontoon would be floated out approximately thirteen feet from the first, and the process continued until the bridge was secured to an abutment on the opposite shore.1

Beginning at 5:00 A.M., the 15th New York Engineers took a little over three hours to complete their bridge below Deep Run, two miles southeast of Fredericksburg. But just as the final balks were going into place, Rebel pickets opened fire, wounding six Federals. A battalion of Regulars from the U.S. Corps of Engineers was supposed to lay another bridge just south of this first span, but manhandling thirty boats down embankments to the water’s edge delayed them until about 7:00 A.M. Two hours later the work party drew fire—and audible curses—from about a hundred of Hood’s Texans. A Confederate major reportedly shouted, “You damned Yankees, go to hell.” One bluecoat was wounded, and two others were taken prisoner before Federal artillery fire scattered the Rebs. By 11:00 A.M. the completed bridges awaited Franklin’s infantry and artillery.2

Sumner’s orders were to cross his grand division, march through Fredericksburg, and seize the high ground behind the town. Franklin was instructed to move down the “old Richmond Road, in the direction of the railroad” and attack the Confederates without waiting for Sumner to begin his assault. The Richmond Stage Road ran to Bowling Green and eventually to the Confederate capital, but not toward the railroad. Army maps, however, mislabeled a country lane branching off toward Hamilton’s Crossing as “Road to Bowling Green.”3 So the long-awaited assault began with vague orders and cartographic confusion; indeed by this time Burnside himself was having second thoughts.

Franklin began crossing his infantry at 4:00 P.M., but Burnside now told him to send over only one brigade to guard the bridgeheads. With the 2nd Rhode Island acting as skirmishers, Brig. Gen. Charles Devens Jr.’s brigade from the Sixth Corps advanced toward the pontoons about sundown with fixed bayonets and grim determination. The men fell into step as a band began to play, but this set the bridges swaying dangerously. Until the music was ordered stopped, it seemed likely that men would be dumped into the icy water. Meanwhile Confederate skirmishers lurking behind a large haystack and swarming around the Bend—a two-story wooden house owned by prosperous slaveholder Alfred Bernard—began sniping at the Federals. A member of the 37th Massachusetts noticed how the men’s faces turned “pale” as they first came under fire, but Union artillery and musket fire quickly scattered the Rebels. The bluecoats fanned out as they reached the western riverbank. Massachusetts troops who entered the Bernard house suddenly found themselves in unaccustomed luxury: artwork on the walls, fine carpets, a seven-foot mirror, a heavy rosewood bed, and a mahogany wardrobe. With the common soldiers’ typical contempt for a wealthy Rebel’s property, they grabbed flour and whiskey, tore down a barn, milked cows, and enjoyed fresh beef.4

Most of Franklin’s men (and some of Hooker’s as well) spent the day marching toward the pontoon crossings and waiting several hours in the mud before finally settling into cold bivouacs. Some officers used the time to deliver spread-eagle speeches, while soldiers hastily scribbled notes home. A Michigan regiment fortunate enough to receive two months’ pay arranged with the chaplain to send the money home before they crossed the river. With the cannonading upstream as backdrop (Federal artillery was pounding Confederate positions in town), they sat on their knapsacks “joking, laughing and eating crackers and pork,” apparently little concerned about what lay ahead. It was the same elsewhere. “The men all seem cheerful and anxious to meet the rebels,” a New Jersey recruit observed.5

Rolling up their blankets against the cold, soldiers drifted off to sleep. Men without fires stirred restlessly in the chill air or stomped about the camps trying to stay warm. Others huddled near the bluffs of the Rappahannock.6 Of course the sometimes overpowering fear of death kept many men awake. During the “terrible suspense” of waiting, soldiers became helpless victims of their own vivid imaginations. “If a man’s knees shake at all,” a Maine recruit observed, “it is while marching the last mile toward the fight.” Anticipation created an agonizing tension. Franklin’s men could hardly expect an uneventful crossing on the morrow, what with the boom of heavy guns along Stafford Heights still in their ears and the certainty of something big happening only a mile or so upstream.7

While engineers working on the lower bridges had encountered only light resistance, all hell had broken loose in Fredericksburg itself. On the night of December 10, after surveying the crossing site near Chatham, Capt. Wesley Brainerd of the 50th New York Engineers had scribbled a note to his father. “To night the grand tragedy comes off. If I am killed and should this meet your eye, please accept it as my ‘good bys,’ remember me to all my friends and I beg of you to look after the interests of my Dear Wife and Little Daughter. And so, dear Father, Good bye.”8

Brainerd stepped out of his tent at midnight, and by 3:00 A.M., undaunted by the bone-chilling fog and the thirty- to fifty-foot bluffs down which the captain’s men had dragged the pontoons, both the 15th and 50th New York Engineers were at work on bridges—two at the upper end of town and one at the lower end (usually called the “middle bridge”). The men could make out the flickering campfires more than 400 yards away on the opposite bank but also noticed them being extinguished. Three hours later, with one of the upper bridges and the middle bridge about two-thirds complete and the other upper bridge about one-quarter finished, Confederate infantry suddenly began popping away at the engineers. The bullets struck lashers, chess carriers, and balk carriers, and a minié ball instantly killed Capt. Augustus Perkins of the 50th New York Engineers. Wounded soldiers flopped into the boats while others crawled back to safety. Four times crews ventured out to complete the bridges but came scurrying back, and by 10:00 A.M. the New Yorkers had suffered fifty casualties, including a seriously wounded Captain Brainerd.9

Alfred Waud, 50th [N.Y.] Engineers Building Pontoon Bridge at Fredericksburg (Library of Congress)

Supporting infantry who berated the fainthearted engineers for retreating too quickly soon had to eat their words. General Woodbury led forty volunteers from the 8th Connecticut onto one of the bridges, but after Confederate fire felled twenty or so, the rest beat a hasty retreat. Two supporting regiments in Hancock’s division also suffered casualties near the upper bridges.10

As some Federals had feared, Lee had been ready for them. Around 5:00 A.M. McLaws ordered two signal guns fired to alert Confederate troops that the long-awaited battle was about to begin.11 Lee of course had for some time recognized that the commanding enemy artillery positions on Stafford Heights meant that his army could not hold Fredericksburg if the Federals chose to cross the Rappahannock there. Nor did he wish to shell the Yankee divisions once they occupied the town. His strategy was to buy time: harass the bridge builders, delay the crossing, and allow Jackson’s scattered brigades to reassemble while Longstreet’s men re-deployed. Should Burnside choose to attack his strong defensive positions, so much the better.12

Longstreet’s corps was stretched thinly along a secure defensive line. Maj. Gen. Richard H. Anderson’s Division held the extreme left extending from Taylor’s Hill to the Orange Plank Road. To his right, perched on Marye’s Heights, stood Brig. Gen. Robert Ransom Jr.’s division. McLaws occupied Telegraph Hill (the site of Lee’s headquarters and thereafter dubbed “Lee’s Hill”) on Ransom’s right. Maj. Gen. George E. Pickett’s and Maj. Gen. John B. Hood’s Divisions were placed along the long ridge from McLaws’s right to Hamilton’s Crossing. Although the commanders were a curious mixture of personalities and abilities—from the stolid Anderson to the untested Ransom, from the steady McLaws to the flamboyant Pickett—there was no gain-saying the strength of their positions.13

Confederate batteries had been placed in rifle pits and behind log breastworks. Ammunition chests had been removed from the limbers and hidden behind the traverses. Because much of the digging had taken place in freezing temperatures and with tools in short supply, there was little protection in these relatively shallow works for either the ammunition or supporting infantry.14 Even as the Federals were laying the bridges, Lee—up early as usual—was fiddling with gun placements and drafting last-minute instructions. He had no intention of engaging the enemy batteries on Stafford Heights, so Longstreet directed Rebel gunners to fire only at the pontoons and infantry attempting to cross, while his artillery chief Porter Alexander kept batteries well concealed behind houses and ridges.15

Given the layout of the town, Confederate artillery was virtually useless against the Federal engineers, so the job of harassing the Yanks fell to Brig. Gen. William E. Barksdale’s Mississippi brigade of McLaws’s Division. A onetime fire-breathing newspaper editor, Mexican War officer, Mississippi congressman, and ardent secessionist, Barksdale proved a brave and resourceful soldier whose stubborn aggressiveness perfectly suited Lee’s needs. Establishing his headquarters on Princess Anne Street at the three-storied Market House, the town’s commercial center, Barksdale stationed the 17th and 18th Mississippi along the riverbank from the upper part of town to a quarter-mile below Deep Run, holding the 13th and 21st Mississippi in reserve behind Marye’s Heights. Once the shooting started, these regiments took supporting positions along Caroline Street, allowing for the movement of troops to any threatened point along the riverbank.

From the warehouses, shops, and houses along Water Street the Mississippians could fire at their enemies on the opposite shore or any body of troops trying to cross the river. Once across, however, Union forces could find shelter under the steep banks on the Fredericksburg side. Although an eventual Federal bridgehead could not be prevented, McLaws intended to make it as costly as possible. Barksdale’s men were dug in along the riverbank behind dirt-filled barricades, and the rifle pits were connected to town cellars by protective “zigzags.”16

Lt. Col. John Fiser, commanding the 17th Mississippi, warned off civilians living near the river when word came that the bridges were being constructed and deployed seven companies along the riverbank. Alert Mississippians had heard bridging material being hauled down from Stafford Heights but were under orders to keep quiet until the Yankees got closer. The fire they opened around 5:00 A.M. had a “stunning effect,” according to Fiser. It drove the bridge builders back repeatedly, and the Federal guns hauled down to the riverbank accomplished little in the fog. Several companies from the 8th Florida had been detached from Anderson’s Division to support Fiser on the left by firing from “point-blank range of the enemy above the [upper] bridge.”

On the southern end of town the right wing of the 17th Mississippi along with several companies from Col. William H. Luse’s 18th Mississippi lined the riverbank with sharpshooters and waited. The bridge builders “were working with the precision of clockwork,” a sergeant later described the scene. “It was a beautiful but solemn and mournful sight; the dark forms of the pontoniers were dimly reflected through the fog in the rippling waters.” Around 7:00 A.M. Rebel musketry drove the engineers from the bridge; according to Luse, Federal infantry support “broke ranks and were with difficulty rallied.” A Richmond newspaper reported with some exaggeration that the Mississippians’ fusillade had “filled the air with the legs, arms, and disjointed members of dead Yankees.”17

Ironically, the Federal engineers might have considered this an accurate description of what had transpired. Despite the completion of the lower bridges, the operation as a whole had been disastrous. The burden of failure was pressing down on Burnside’s shoulders. Up by 4:00 A.M., the Federal commander spent most of the day at his headquarters in the Phillips House, a recently abandoned, two-story brick Gothic Revival structure complete with elaborate furnishings (even indoor plumbing) located a mile east of the river on the higher shelf of Stafford Heights and offering a panoramic view of Fredericksburg. Burnside, however, hardly enjoyed the scene spread before him. Increasingly impatient and then furious as the Rebels thwarted the engineers, Burnside finally ordered his artillery chief, Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt, to “bring all your guns to bear upon the city and batter it down.”18

A longtime McClellan supporter, the opinionated Hunt had undeniable tactical skills. Appalled by gunners who squandered ammunition, Hunt preached appropriate rates of fire at various distances. On the evening of December 10 he had placed his guns along a nearly five-mile line from above Falmouth to Pollock’s Mill opposite the Confederate right flank. The daunting mission of these batteries was to “control the enemy’s movements on the plain,” to “reply to and silence” Confederate batteries along the high ground behind Fredericksburg, to “command the town,” to protect the bridge builders and their supporting regiments, to cover troops crossing the pontoons, and to secure the army’s somewhat vulnerable left flank. Hunt divided some 147 guns into four sections, each with several specific tasks. The early morning fog, however, thwarted Hunt’s gunners. Even after the mist began to lift, heavy cannonading silenced Barksdale’s sharpshooters only momentarily, and the Rebels quickly resumed their murderous fire on the pontoniers. Eyewitnesses testified to the deafening noise of the artillery fire (a Massachusetts recruit described it as louder than at Antietam—impressive if true) and its earth-shaking force. This early barrage, however, largely wasted ammunition, and the bridge building remained at a standstill. Hunt later claimed that he opposed Burnside’s order to shell the town and considered such an action “barbarous,” but no contemporary evidence supports his story. Given Hunt’s own description of the artillery’s mission, it is more likely that at the time he shared Burnside’s angry impatience over an entire army being delayed by a few infantry regiments.19

The heavy fog was lifting at 12:30 P.M. as Hunt’s men prepared, in the words of a section commander, to “open a rapid fire along the whole line, with the object of burning the town.” The Yankee guns on Stafford Heights were soon hurling solid shot and shells into Fredericksburg. A second lieutenant in Battery A, 5th U.S. Artillery, reported that his four 20-pounder Parrotts got off nearly 500 rounds that day. Other outfits reported an average closer to 50 rounds per piece. The larger guns husbanded precious ammunition. With the town shrouded in haze and smoke, the 4.5-inch rifles of the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery in the left center section fired off a round every ten to fifteen minutes with what its commander guessed was “considerable effect.”20

It was the most intense bombardment they had ever heard, several eyewitnesses reported. The great guns seemed to fire ever more rapidly, and men ran out of words to describe what they saw and heard.21 They strained to recapture the frightening cacophony of so many cannon. “Talk of Jove’s thunder,” a Buckeye scribbled in his diary. “Had the ancients heard so frightful and so incessant a noise they would have sunk into the ground with terror.” Others wrote of a “sharp” report or “deep thunder,” of a “hissing, whizzing, whirring, screeching sound” as shots and shells of various sizes flew across the Rappahannock. A New York private noted the “loud purring” of the solid shot and “musical singing” of shells that together “made the grandest discord of sound I have ever heard.” Some slaves in the area decided that “judgment day had come.”22

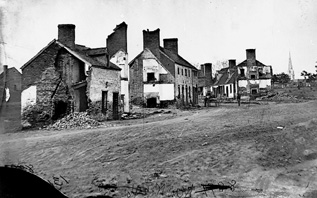

Destruction in Fredericksburg (National Archives)

It seemed so indeed for the town of Fredericksburg. Watching buildings collapse under the bombardment, a New Hampshire soldier thought the place was becoming “a hell.” After two hours of intense artillery fire, entire blocks lay in ruins with only walls standing as stark reminders of what had once been homes or businesses; the elm trees in front of one fine mansion had been “pierced, torn, twisted or split asunder.”23 Solid shot turned many homes into what a Connecticut recruit aptly called “complete pepper-boxes.” Ninety-eight cannonballs had reportedly hit a single residence on Caroline Street. In one house a solid shot smashed a fine piano; in another a shell struck a child’s playhouse, scattering toy dogs and dolls around the room. Hardly a building remained unscathed. The town had been knocked to pieces.24

The bombardment of Fredericksburg seemed to raise the war’s barbarity to an ominously higher level. There was no sanctuary; nothing seemed sacred. Sighting their guns with precision, young artillerists even targeted houses of worship. Taking aim at the town clock in St. George’s Episcopal Church, a two-story brick Romanesque structure on the east side of Princess Anne Street, Union gunners nicked the spire and sent one shell through a wall. A nearby Baptist church was hit a score or more times.25

For observers with an apocalyptic turn of mind, the sight of the church steeples poking above the fog and smoke was unnerving, and the outbreak of fires heightened the sense of judgment and doom. Watching the batteries flash in the gloaming, a member of the Irish Brigade saw a “sheet of flame” appear to engulf the town. Between twenty-five and forty buildings were badly burned, and later visitors noted blocks of charred ruins.26 Oblivious to the noise and destruction, some veterans sat, ate, repeated stale camp jokes, or listened to a band playing “The Girl I Left Behind Me” over the racket. But most soldiers could not take their eyes off the artillery spectacle, the most engrossing sight they had seen for weeks.27

The destruction of what many Federals conceded had once been a charming town strained the power of language. The roaring cannon and sharp crack of small arms fire seemed almost beyond description. A New Jersey man wrote of a “tremendous rain of shot and shell,” but this likely would have struck many soldiers as far too tepid. Words such as “magnificent” and “sublime” often appeared in diaries and letters. But many soldiers penned paragraphs and pages whose evocative powers still somehow fell short.28 Part of the problem arose from a painful moral ambivalence. Many Union soldiers could not watch the bombardment of Fredericksburg with either awe or equanimity. The devastation of Rebel property might be easily justified or even welcomed, but the historical associations of the town with Washington and the founding of the republic also made its destruction profoundly sad. Some of the gunners and even spectators felt twinges of conscience. “There are many things connected with this war that seem hard for an enlightened and Christianized nation such as we claim to be,” a New York volunteer confessed to his mother.29

Watching the cannonade, the Confederate high command seemed both fascinated and appalled. “These people delight to destroy the weak and those who can make no defense; it just suits them,” Lee fumed. Yet even these words—harsh by the Virginian’s usually genteel standards—exhibited a steely self-control. While the Federal artillery on Stafford Heights commanded the town, Lee still hoped “to damage them [the Union forces] yet.” Such staunch determination filtered down in the ranks, though some men also expressed a fervent desire for bloody vengeance. Brig. Gen. Winfield Scott Featherston instructed his brigade on the Confederate left to shoot the Federals just as they would a bear or squirrel and reckoned his boys could “whip the whole Yankee army.”30

Barksdale’s tenacious defense doubtless bolstered such confidence. Although the men of the 17th Mississippi thought the bombardment “the most terrific they were ever under,” they held their positions—but not without a price. One private “had his brains splattered by a shot”; another was severely wounded by a bounding cannonball. Walls and chimneys came tumbling down, and falling bricks killed or severely injured several men. As Barksdale and his staff munched on hardtack dipped in honey—a rare treat—a Parrott shell fell in their midst. Although it did not explode, a piece of slate fell off a building and badly bruised the general.31

Even during the shelling Barksdale skillfully shifted various companies to shore up defenses along the riverbank. Most of the 8th Florida anchored the left wing of the 17th Mississippi until around 11:00 A.M., when a wall collapsed on its commander, Capt. David Lang. The regiment’s performance suffered accordingly. Three companies (along with several others from the 21st Mississippi) were detached to support the right wing of the 17th Mississippi in its defense of the middle pontoon crossing along the wharves. The Floridians proved utterly worthless. Their new commander, Capt. William Baya, repeatedly disobeyed orders and refused to fire at the pontoniers for fear of attracting attention from Federal artillery. But who could blame these men for wanting to escape the firestorm? A courier in the 18th Mississippi had earnestly prayed that he not disgrace the family name by any cowardly act as he dodged shot and shell. He soon needed all the help the Lord could provide as he saw one fellow’s head torn off by a shell and three other men fall wounded.32

Despite the intense cannonade, Barksdale’s brigade stood firm. As the guns fell silent around 2:30 P.M., Yankee engineers scrambled out to complete their work, but again the Mississippians drove them back. Nine times Fiser’s men had stopped the bridge builders, and even the usually impassive Lee beamed over each report of another repulse. Barksdale offered to help douse the fires ignited by Federal shells, but Longstreet told him, “You have enough to do to watch the Yankees.” The Mississippians were of course doing much more: Barksdale bragged that he would present Marse Robert with “a bridge full of dead Yankees.”33

Along Marye’s Heights, Confederates cheered the stout resistance but watched the bombardment with horror, fascination, and awe. Porter Alexander claimed then and later that this was the greatest artillery barrage he ever witnessed. Lt. Edward Patterson of the 9th Alabama was at once aghast and enthralled by the sights and sounds: “Never before have I ever witnessed a scene of such terrible beauty. Or heard music so grand, at the same time so mournfully beautiful.” After rambling on about “shrieking” shells, booming guns, and the flashes of fire from Stafford Heights, he finally despaired of recapturing the scene: “But why attempt a description of that which is indescribable? Words are too barren, they are powerless to convey to the mind a picture that can in any way compare with the reality.”34

For the inhabitants of Fredericksburg, terror overwhelmed any sense of sublimity. For several weeks civilians had nervously watched for signs of Federal movements. “I have breathed under this roof,” one woman had told a British reporter at the end of November, “living I cannot call it.” But when the attack had not come immediately, refugees had drifted back to their homes. As the guns began booming on the morning of December 11, hapless civilians scrambled for their basements, and a few even crawled into wells or cisterns. Damp cellars, however, were not always safe havens. The local postmaster’s house caught fire, forcing the family into the garden; they spent the day cowering behind a plank fence. In Jane Beale’s house on Lewis Street, a Presbyterian minister led a frightened group in reciting the Twenty-seventh Psalm. Just as a 12-pound shot struck the building, they reached the verse “Though an host should encamp against me, my heart shall not fear.”35

Maybe such piety had some effect, because the civilian death toll was amazingly small—probably no more than four people, two of each race and gender—but details on these casualties are sketchy. Rumors bespoke other deaths. On December 12 a New Jersey chaplain visited a man struck by a shell fragment and not expected to live. A Mississippi soldier heard that a fleeing mother had been killed by a shell, leaving her screaming baby covered in blood. Whether true or not such stories reaffirmed deeply held convictions about Yankee barbarism.36

The sight of more refugees fleeing from Fredericksburg—some from burning houses during the height of the bombardment—intensified Confederate outrage. As terrified civilians dodged falling shells, members of the Washington Artillery wagered whether one poor fellow would safely reach Marye’s Heights. Men, women, and children escaped in whatever was available—ambulances, carriages, wagons, or carts—or they hurried along on foot toward the Confederate lines and safety. Some had no coats; others made do with what was handy. One woman wrapped herself in an ironing board cover for her flight along the Plank Road.37

Elderly people, many of them frail and ill, were finally driven from their homes and staggered along, sometimes carrying heavy bundles. But women and young children with little more than the proverbial clothes on their backs presented the most heartrending sight and sure grist for Rebel propaganda. Many Confederate soldiers could vividly recall their wails and piercing screams years later. Despite some embroidering, the Richmond Daily Examiner described real suffering: small children, “their little blue feet treading painfully the frozen ground, blindly following their poor mothers who knew as little as themselves where to seek food and shelter.” The “distressing sight” of women and children running from burning buildings even touched the hearts of some Federal artillerists.38

David English Henderson, Departure from Fredericksburg before the Bombardment (Gettysburg National Military Park)

Not many Confederates would have believed that a damned Yankee could harbor any tender feelings. It was just like those black-hearted fiends to shell a town filled with women and children. Recounting the horrible scenes, many soldiers vowed vengeance. Some men gave the piercing Rebel yell as women and children passed through their ranks. Others offered the poor refugees their own meager rations. The news of the bombardment and exodus spread quickly. In a nearby county one young woman, eager for retribution, longed to hear that Philadelphia or New York or Boston was in flames. Northern savages now warred against women and children, trumpeted the Richmond press. “The most unprovoked and wanton exhibition of brutality that has yet disgraced the Yankee army,” declared the Richmond Daily Dispatch. “Modern Goths and Vandals,” fumed the Lynchburg Daily Virginian. The women’s nobility and stoicism (forgotten for the moment were their screams and cries) won universal praise. Watching refugees flee from the “vile fiends of Lincoln,” a Georgia infantryman felt “proud” of “being able to render assistance to these unfortunate females.”39

At least Barksdale’s men had repulsed the Yankee engineers. Burnside was nearly beside himself when the bridge builders—even after the artillery barrage—still could not finish their work. He remained adamant that the pontoons had to be completed that day. Hunt and Woodbury finally suggested that volunteers cross the river in boats, establish a bridgehead, and drive the vexing Rebels out of town.40

The task of leading what was immediately dubbed a “forlorn hope” fell to the 7th Michigan (Col. Norman J. Hall’s brigade, Howard’s division), a veteran regiment already bloodied at Fair Oaks and Antietam. Led by Lt. Col. Henry Baxter (soon to be wounded during the crossing), around seventy men sprang from the riverbank willows and bushes, pushed three pontoon boats from shore, and jumped in. From Chatham, Clara Barton heard their voices echoing, “Row! Row!” as Barksdale’s troops began plugging away once more. While a few reluctant members of the 50th New York Engineers rowed the boats, the Wolverines lay flat in the bottoms. Once they were out about 100 yards, the high bank on the Fredericksburg side afforded them some protection. Even before the boats had landed, men jumped out, splashed ashore, and began clambering up to Water Street to the left of the pontoon crossing.41

The Yankees quickly bagged some thirty prisoners. Barksdale’s troops fell back to Caroline Street, where they stoutly resisted any further Federal advance. No longer able to hold his position, the general realigned his forces to contain the bridgeheads and control as many of the streets running toward the river as possible.42

Closely behind the 7th Michigan came the 19th Massachusetts, another veteran outfit in Hall’s brigade. After landing, they deployed in houses along Water Street to the right of the pontoon crossing. Advancing toward Caroline Street, they came under a “shower of bullets” from Barksdale’s men, who had squirreled themselves away in houses and cellars and behind barrels, boxes, and fences. Stout Confederate resistance exacted a high price for the advance. Company B lost ten of its thirty men in five minutes, and the regiment finally had to withdraw with heavy losses. The street fighting had proved especially nasty. One wounded Massachusetts private had reportedly been bayoneted seven times by Rebels, and a story later circulated that four of Barksdale’s men had been “killed in cold blood by the Yankees.” The Federals, now under orders to bayonet any Confederates found firing from a house, took few prisoners.43 Although most soldiers still hesitated to carry out such edicts, the growing savagery of the war had immediate consequences for Fredericksburg. This brief but brutal fight seemed to unleash a new blood lust on both sides.

After the engineers resumed their work and with one upper bridge finally completed around 4:30 P.M., the remaining regiments in Hall’s brigade started across. As the troops squeezed into a four-block area, Hall finally ordered the 20th Massachusetts, which because of confused orders had crossed the river in boats, to “clear the street leading from the bridge [Fauquier Street]” of Barksdale’s men. These members of the famous Harvard Regiment, commanded by Capt. George N. Macy, proved equal to the task. The men scrambled up the riverbank and, as they moved toward Caroline Street in column by companies, suddenly came under intense fire. A Fredericksburg citizen dragooned into guiding the regiment through the streets fell dead at the first volley. Marching four abreast, the Massachusetts troops provided easy targets for Barksdale’s concealed marksmen. Bluecoats “began dropping at every point,” Pvt. Josiah Murphey recalled. He soon became one of the casualties. Turning to his left to fire down Caroline Street, nineteen-year-old Murphey was suddenly hit in the face, fell to the ground, and “cursed the whole southern confederacy from Virginia to the gulf of Mexico.” But despite heavy losses, the Bay Staters forced their way into houses and drove Barksdale’s weary soldiers out. When the regiment appeared temporarily stalled, Macy prodded his men with sulfurous oaths, which he did not hesitate to shower on the 7th Michigan when it refused to advance. Macy and the intrepid Capt. Henry L. Abbott, despite the growing darkness, mounting casualties, and milling confusion, kept re-forming their men and pushing them toward Princess Anne Street, where Barksdale had rallied most of his troops.44

But the regiment’s losses were staggering. An advance of no more than fifty yards had cost more than 100 men, and altogether over a third of the 335 soldiers who had crossed the Rappahannock were now casualties. The streets, according to Lt. Henry Ropes, were “heaped with bodies.” But cold numbers hardly convey the human price of battle. Company I, composed largely of sailors and fishermen from Nantucket Island, had suffered injuries ranging from superficial to mortal. Hit in the right big toe by a spent ball, lanky nineteen-year-old Pvt. James Barrett was in great pain. A minié ball had fractured the left knee of Pvt. Jacob G. Swain. Two days later the eighteen-year-old had his leg taken off at the lower third of the thigh; he would not survive a second amputation the following fall. Pvt. Albert C. Parker, a blue-eyed, sixteen-year-old shoemaker, took a bullet through his penis and suffered permanent disability. The good luck of others stood in striking contrast. Another shoemaker, twenty-one-year-old Pvt. George C. Pratt, reported sixteen bullet holes in his uniform but not a scratch on him. The officers noted what Macy termed “fearful” losses but also basked in praise for their conspicuous gallantry. Capt. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. doubted there was a better regiment in the entire Army of the Potomac.45

Barksdale’s troops shared in both the encomiums and the blood: nearly 30 killed, some 150 wounded, and more than 60 taken prisoner or missing. The official tabulation of the numbers and names required over three tightly packed pages. But again such lists tell very little of the human story. “The Rebs lay thick along the fence just as they had fallen,” a lieutenant in the 19th Massachusetts noted in his diary. “Killed by our round shot and shell. Some with heads off, others arms and legs off, and some mutilated in a horrible manner.” Several Mississippians joined their Federal counterparts on the amputation tables. Cpl. J. W. Alexander of the 13th Mississippi lost both legs; Sgt. A. D. Sadley of the 21st Mississippi lost his right leg and his left foot. A member of the 17th Mississippi survived to mourn his brother, whose body soon lay in a “cold grave upon the banks of the Rappahannock.” He recalled their childhood frolics and most of all their love. It was so hard to imagine losing a brother even with the assurance they would soon meet in a “better world.”46 For each of the dead, someone undoubtedly felt a similar grief because valor exacted such a high price.

But to Lee and his generals the price seemed worth paying. Barksdale’s men had delayed the Federal crossing longer than anyone might have expected or even hoped. At the middle pontoon crossing the 18th Mississippi, despite some belated support from two other regiments in McLaws’s Division, had to retire for fear of being flanked. Shortly after 3:15 P.M. 100 men from the 89th New York crossed the Rappahannock in four pontoon boats. Storming buildings in groups of twenty-five, by 4:00 P.M. they had cleared the lower part of Fredericksburg. In thirty minutes the middle bridge was complete. The New Yorkers gobbled up more than sixty prisoners, most of whom were from the ineffectual Florida companies deployed along the river.47

About 7:00 P.M. McLaws ordered the remnants of the Mississippi brigade withdrawn from Fredericksburg. According to Longstreet, Barksdale remained so “confident of his position that a second order was sent him before he would yield the field.” Yet the collapse of his line in the lower part of town and the danger to his forces along Princess Anne Street posed by the repeated attacks of the bloodied but unbowed 20th Massachusetts made a retreat wise if not imperative. To bring his men back through the streets before dark, however, would have risked coming under deadly Federal artillery fire, so Barksdale’s reluctance was understandable. The 21st Mississippi was assigned to cover the withdrawal, but when Lt. Lane Brandon learned from prisoners that one of his old Harvard classmates, Captain Abbott of the 20th Massachusetts, was leading a Yankee platoon, he kept counterattacking until he was finally placed under arrest for disobeying orders. All in all, Barksdale handled the retreat deftly, and soon his command was resting behind a stone wall at the base of Marye’s Heights.48

At last Burnside had his bridges. At the Phillips House the prevailing assumption remained that the Army of the Potomac had finally stolen a march on Robert E. Lee. Burnside was pleased, reporting “very slight losses,” the river spanned, and troops crossing. There were even plans for Haupt to rebuild the railroad bridge across the Rappahannock.49

The Federals appeared ready to strike a decisive blow. Realizing the necessity for prompt action, Halleck pressed for sending reinforcements into Fredericksburg during the night. Even as the 20th Massachusetts slugged it out with Barksdale’s men in the streets of Fredericksburg, the rest of Hall’s brigade was crossing the upper bridges. As these troops quickly moved to support their comrades engaged in the bloody street fighting, they came under Rebel artillery fire. Although the shelling produced lethal results, General Howard admonished some of the enlisted men that attempting to dodge projectiles was futile. But when a shell whizzed over the general’s head, he instinctively ducked. This amused men in the 127th Pennsylvania who had just seen one of their officers struck down by a shell fragment and now mockingly repeated the general’s advice. “Dodging appears to be natural,” Howard good-naturedly conceded.50

The rest of Howard’s men endured scattered Rebel artillery fire and helped drive the last of Barksdale’s sharpshooters from several houses. At one street corner a Massachusetts volunteer counted at least fifteen dead bluecoats; other men noticed Rebel bodies lying in the streets.51 Around 8:00 P.M. Col. Rush C. Hawkins’s brigade from Burnside’s old Ninth Corps tramped across the middle pontoon bridge. The boys cheered as they entered the lower part of Fredericksburg, and pickets fanned out onto the now eerily deserted streets. Ordered not to sleep, some soldiers began building fires.52

The Federals had secured the town, but Lee was satisfied, in fact more than satisfied. He had managed to delay the Federal crossing long enough for Jackson to bring in his dispersed divisions the next day. Moreover, Burnside seemed hell-bent on attacking the strongest defensive positions Lee’s army had ever held. Each new report of more bluecoats coming over the bridges appeared to light his face with anticipation. Like the Federals, however, many of Lee’s men had spent an uncomfortable day waiting. Some read old letters from families and sweethearts one last time, and most nervously anticipated what the next day might bring.53

They could hear the Federal troops crossing the bridges. Those men closest to the enemy in town dared not have fires on a night when temperatures again plummeted into the twenties. One picket in Brig. Gen. Joseph B. Kershaw’s brigade froze to death, and many men stayed up all night just to keep warm. Other Rebels set several haystacks and fence rails afire. Wrapped in blankets and bedded down for the night on frozen ground, most could have echoed the words of a soldier on the extreme left of Lee’s line: “We sleep on our arms tonight and expect bloody work tomorrow.”54

As did the Federals on both sides of the Rappahannock. Like Franklin’s men to the south, most of Sumner’s troops had spent the day marching toward the river and then back, waiting in the mud, trying to sleep, writing letters, and talking. But thousands had also watched the engineers trying to bridge the Rappahannock, and the opening of Hunt’s massive artillery barrage had sent hearts pounding. Inactivity and suspense were almost worse than advancing into line of battle, many said. Even as onlookers, they sometimes fell victim to a stray Rebel shot. After marching down to the Rappahannock in the midst of the bombardment, a Connecticut soldier recalled, his regiment doubled back to camp “in rather a sullen humor.”55

The bluecoats also noticed ominous signs of what lay ahead. The sight of a wounded soldier lying on a sheet soaked with blood and being pulled along on an artillery caisson, his left side opened up and part of his arm torn off by a shot, suddenly brought a seventeen-year-old boy in the 12th Rhode Island face-to-face with mortal danger. He imagined himself being carried off the field while his loved ones at home fretted over his fate. Though loath to believe that their generals would order them to attack such stout defenses, many Union soldiers prepared to meet their maker. “If I could only feel that I was a Christian, I would go cheerfully,” declared one Connecticut volunteer. He had tried to serve his country and his God but was painfully aware of his shortcomings. Most of his comrades, he suspected, were even less prepared to finish their life on earth.56

Sunset brought the day to a merciful close. The gathering darkness highlighted the flash of cannon, burning fuses arched across the dark sky, and bursting shells briefly illuminated the town. Some of the Yankees lost their bearings in the crowded streets. A sergeant and his squad of eleven men from the 127th Pennsylvania stumbled onto a Confederate patrol and were soon on their way to Libby Prison in Richmond. Meanwhile some of their comrades discovered more Rebel casualties in the second story of an old stone house; one poor fellow, severely wounded in the legs and slowly bleeding to death, begged the Pennsylvanians to finish him off. Many soldiers tried to escape these horrors by sleeping, but on both sides of the river the cold air and frozen ground made any rest fitful at best. Like the Confederates, some Federals simply paced about to keep their blood circulating.57

Church bells sounded during the night. Whether they were ominous portents or sources of familiar comfort depended on one’s perspective. Badly weakened by loss of blood, Captain Brainerd sat on a chair in a large room of the Lacy House. All around him men cried, groaned, sank into sleep, or died. In Fredericksburg itself, Federals gathered in the streets, eating, drinking, smoking, and talking quietly about the battle to come. Although some would later claim that on this night they could see nothing but disaster ahead, at the time their opinions were mixed. A certain buoyant optimism had not entirely vanished from the Army of the Potomac. The men of the Irish Brigade, according to one witness, appeared to be in “excellent spirits” and welcomed rumors that other Federal armies were converging on Richmond and Petersburg from the east.58 After all, Burnside had at last gotten troops across the river, and the campaign could proceed in earnest. The drive on the Confederate capital would now be launched. Lee, of course, had other ideas.