13 Breakthrough

Go into emptiness, strike voids, bypass what he defends, hit him where he does not expect you.

—Ts’ao Ts’ao

With Confederate artillery apparently neutralized, the next steps seemed obvious: an advance through the fields and across the railroad tracks, then a charge up a hill and into the Rebel lines. But what reads like one great effort in a battle narrative was in reality much more halting and confused. Even well-drilled regiments—not to mention brigades—do not move as units. Soldiers themselves, mouths dry, breathing difficult, and a generally heavy feeling, were hardly the proverbial well-oiled cogs in a military machine. Men already nervous amidst smoke, noise, earth-shaking reverberations of the artillery duel, and the thud of sharpshooters’ bullets against human flesh now prepared for the test of courage. Some yelled or cursed to relieve the tension. Meade jokingly suggested to Col. William McCandless of the 2nd Reserves that he might soon earn a brigadier’s star. “More likely a wood overcoat,” the colonel sardonically replied.1

At 1:00 P.M. Sinclair’s brigade with Feger Jackson to the left and Magilton following began moving past the artillery and down toward the railroad. As the exhausted artillerists shouted at the infantry to do their duty, Meade came across one terrified soldier who remained immobile until whacked hard with the flat of the general’s sword.2 The man could easily catch up with his outfit because, from the first, this advance illustrated the differences between battles fought in textbooks, plans laid out on maps, and attacks by flesh-and-blood soldiers.

In the confusion Sinclair, only twenty-four years old and new to brigade command, apparently forgot about the 13th Reserves and left them behind with the artillery. The rest of his mud-spattered soldiers, along with Feger Jackson’s and Magilton’s troops, trudged through the marshy stubble fields, scrambling into or simply vaulting three ditches. Confederate infantry fire from the other side of the railroad and Rebel artillery rounds attended them the whole way. One member of Magilton’s brigade considered this spot worse than the famous cornfield at Antietam.3 Sinclair’s men, heading directly into the gap between Lane and Archer, crossed the tracks and entered the woods with little trouble. But thick woods, mucky ground, and sheer terror were breaking up the formations; dense vegetation obscured the view on both sides; and regimental command was breaking down as men stumbled rather than surged forward.4

Slogging uphill through the undergrowth and expecting at any time to run into Rebels, Sinclair’s men nevertheless had found the weak point in Jackson’s line. But how could they exploit their good fortune? The difficult terrain played havoc with organization. “Regiments separated from brigades, and companies from regiments” amidst “all the confusion and disorder,” Meade wrote later. This antiseptic description hardly recaptured the frightening disorder of this halting advance. Sinclair himself had been wounded crossing the railroad, and McCandless now “commanded” a brigade no longer functioning as a brigade.5

The 1st and 6th Reserves had already brushed aside one or two small groups of Confederates when they neared a line of stacked rifles. These belonged to Maxcy Gregg’s brigade of South Carolinians. A bookish, fervent disunionist and capable general nearly fifty years old and rather deaf, Gregg had evidently overlooked the tactical importance of the gap between Lane and Archer or his brigade’s potentially precarious position. Concern that his men might accidentally fire into retreating Confederates outweighed the possibility of charging Federals appearing in his front. To avoid casualties from friendly fire, Gregg had ordered his men to stack arms, and many huddled under trees to escape Federal artillery rounds. What one officer later described as a “dense forest mostly of small saplings” prevented both sides from seeing more than fifty yards in front of them. The Pennsylvanians first hit Orr’s Rifles on the right of Gregg’s line with a powerful volley. The South Carolinians returned fire, and soon the bullets were flying among the trees. Finally hearing the ruckus, Gregg rode over and loudly ordered the firing stopped. Officers barked out their commands: “Let the guns alone! Lie down! Those are our men in front!” Arguments broke out among Gregg’s troops about whether they were shooting at Yankees or Archer’s pickets in retreat. Suddenly the Pennsylvanians overran the position, and the fighting became hand-to-hand. Gregg fell from his horse mortally wounded by a bullet in his spine. Now thrust into command, Col. Daniel H. Hamilton of the 1st South Carolina tried to save the brigade by throwing back his right wing to hold off the charging Federals.6

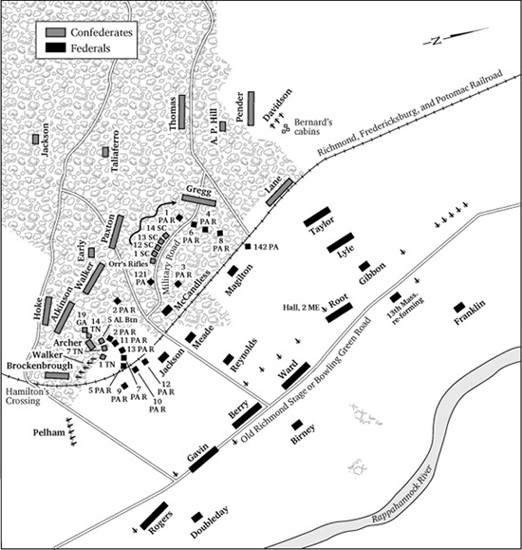

Meade’s attack and breakthrough, December 13, noon–1:00 P.M.

Meade’s men were now astride the military road, and Burnside’s objective of cleaving Lee’s army in two appeared to be within their grasp. The South Carolinians could do little but hang on and wait for reinforcements. Together Orr’s Rifles and the 1st South Carolina suffered nearly 250 casualties, with a heavy toll among the line officers. Although the situation appeared desperate, Stonewall Jackson’s deep formation remained largely intact. The Pennsylvanians had been extremely lucky to overrun a brigade with only two regiments. The laggard 13th Reserves had eventually advanced up Prospect Hill, and after some meandering through the woods, the 2nd Reserves had reached the crest, where they now turned toward Archer’s temptingly unsecured left flank. The rookie 121st Pennsylvania had not gotten far beyond the railroad.7

Without support Sinclair’s men could neither maintain their position nor exploit the breakthrough. For a time, however, it appeared that the Federals would widen the gap and that more regiments would attain the crest of Prospect Hill. Not only had the Pennsylvanians swept past Archer’s brigade; they now threatened to destroy it. Although “Little Gamecock” Archer had barely arrived from sick leave in Richmond to take command, he was a courageous, inspiring fighter. At the start of the Union assault Archer had instructed his troops to hold their fire until the enemy reached the railroad. He fretted about the gap in the Confederate line and about being outflanked, but his men peppered Feger Jackson’s brigade with great effect. The “pop, pop, pop” of musketry fire had been “fearful,” recalled a member of the 19th Georgia. Ironically this fusillade had forced some Federals to oblique into the lip of woods and thus right into the gap between the two Rebel brigades.8

But just as Archer’s men were reveling in their apparent repulse of Meade’s troops, all hell broke loose in the woods to their left. The 2nd Reserves and probably the 11th Reserves (one of Feger Jackson’s outfits that had managed to cross the railroad) stumbled onto the Rebels’ flank and began blasting away at the 19th Georgia from the left and rear. “They were slaughtered like sheep,” claimed Adj. Evan M. Woodward of the 2nd Reserves, and for once such a cliché seemed both apt and accurate. The Pennsylvanians poured their fire directly into a shallow rifle pit, leaving the poor Georgians unable either to defend themselves or flee to safety.9 After holding for about fifteen minutes, the Confederates “gave way,” and men scurried off with their heads covered to avoid the flying lead. But soon the 7th Reserves were also shooting into the Rebels from the front. Caught in the deadly crossfire that also struck the 2nd Pennsylvania Reserves, the Georgians desperately tried to surrender. Only when Woodward waved his hat between the two sides, jumped down into the depression, and asked the Rebels to give up the fight did one of the Georgians shout back, “We will surrender if you will let us.”10 The surviving Georgians would be a skeleton force at best.

Thus the 14th Tennessee was left to defend the exposed left flank. After a bullet whizzed past one man’s knee, he assumed it had come from a Confederate rifle and shouted for the “damned fools” to stop shooting; but he soon discovered that it was bluecoats hitting them from behind. Seeing Federals advancing through some small pines, Lt. Col. James W. Lockert ordered a retreat, later conceding that his troops “fell back in disorder.”11

Officers and men in regiments on the brigade’s right cursed these seeming cowards and reportedly fired into their fleeing comrades, but soon enough several companies in the 7th Tennessee also abandoned their position. Part of this regiment, however, along with the 1st Tennessee, stood its ground and fought until its ammunition was exhausted. Despite the severe wounding of several officers, these troops had stemmed the rout, but they would not be able to hold long without help. According to Archer’s sobering arithmetic—and his bitterness was apparent even in his official report—the gap in A. P. Hill’s line had cost the brigade nearly 250 killed or wounded and more than 150 missing (many captured).12

Having earlier absorbed the full fury of Archer’s rifles, the men of Feger Jackson’s brigade would have taken grim satisfaction in these numbers. Their commander was a bundle of contradictions. Born during the War of 1812, a Quaker who nevertheless had served in the militia, he volunteered in the Mexican War and enlisted again in July 1861. His Civil War record to date was spotty and slightly mysterious. Taken ill during the Second Bull Run campaign, his participation in the battles of South Mountain and Antietam is difficult to document. According to a Union nurse, Jackson was a “hard drinker and very profane”—not exactly a rarity in the Army of the Potomac. Yet there is no evidence that his reputed fondness for the bottle interfered with the performance of his duties.13

Certainly the task he faced early in the afternoon of December 13 might well have called for a stiff shot of commissary whiskey. Advancing to the left of Sinclair toward the Confederate position (with the 13th Reserves filling in the gap between the two brigades), Feger Jackson’s men approached the railroad and laid down a heavy fire against Rebel skirmishers on the other side of the roadbed. Just as the Federals began crossing the tracks less than 200 yards away, Archer’s men (right before the devastating assault on their own left flank) had unloosed several effective volleys. Fascinated and horrified, the Rebels watched scores of Pennsylvanians fall dead or wounded; those not hit appeared both confused and terrified. The 13th Reserves—the famous “Bucktails,” known for their excellent marksmanship and deer tails on their caps—managed to reach the other side of the railroad, push into the woods, and even later support the attack on Archer’s flank. But in the process they suffered horrendous casualties. Many of these Pennsylvanians scrambled for immediate shelter in the railroad cut and seemed “to melt away as did the mist of the morning before the sun,” one member of the 14th Tennessee recalled.14

Unlike Sinclair men’s, who had swept into the gap, Feger Jackson’s troops made little headway. Coming under heavy fire, the 9th Reserves crowded behind a stone fence well short of the railroad. Separated from the rest of the brigade, they nevertheless managed to snipe away at Confederate artillerists. To their right the 10th and 12th Reserves hugged the railroad embankment while shooting at Archer’s men. Some of the Pennsylvanians reportedly fired sixty or more rounds while taking a fair amount of punishment themselves. Watching from near the railroad, a frustrated Meade decided that Feger Jackson should move to the right and into the woods, but the young lieutenant delivering the orders took a fatal bullet in the chest. Another Confederate shot struck Feger Jackson’s horse, throwing the general to the ground. As he attempted to lead his men on foot toward the woods, a bullet entered his skull above his right eye, killing him instantly. With their brigade commander dead, only the 5th and 11th Reserves managed to cross the railroad. Of all Meade’s brigades, Feger Jackson’s would accomplish the least, but it still paid a heavy price: 56 killed, 410 wounded, and 215 captured or missing.15

Despite breaching the Confederate line, Meade’s assault was breaking up and losing its momentum. Sinclair’s men had crossed the railroad, with the Second Brigade only 100 yards behind. Col. Albert Magilton, a classmate of Stonewall Jackson’s at West Point and a veteran of the Seminole and Mexican wars, was also new to brigade command. As with Sinclair’s and Feger Jackson’s, his troops would not function as a brigade for long. Moving forward in tight formations, some of his troops got turned around as they came first under artillery fire and then withering musketry from Archer’s brigade. After a brief rest on the railroad embankment and in the ditches, a sergeant in the 7th Reserves stirred them into action again. “Wide awake, fellows, let’s give them hell,” he hollered. The regiments attempted to charge, but they lost all organization in a mad dash for the woods and scurried for cover in the undergrowth. Companies stumbled forward almost blindly, either lacking or misunderstanding their orders. The 7th Reserves drifted to the left, came under fire, and gained some ground before joining the attack on Archer’s left.16

After crossing the railroad, two of Magilton’s regiments, the 3rd and 4th Reserves, followed Sinclair up Prospect Hill. Both headed toward the military road. The 3rd Reserves got within sight of the Rebel ambulance train and hospital tents but found themselves isolated and without support, vulnerable to a Confederate counterattack.17

Magilton’s remaining regiments—the 8th Reserves and the 142nd Pennsylvania—advanced only a short distance before they were hit hard by Lane’s North Carolinians. Three companies of the 142nd crossed the railroad and charged into the woods with a yell when “a terrific and most galling fire from the enemy’s rifle-pits” staggered them. The Pennsylvanians returned fire, but Magilton ordered them to stop because he believed—wrongly as it turned out—that one of Sinclair’s regiments lay ahead of them. This mistake contributed to the 250 casualties the regiment suffered in less than an hour of fighting. The 8th Reserves also lost nearly half their strength, and neither regiment had achieved very much. In his diary Sgt. Franklin Boyts of the 142nd recorded the theme of the day for Meade’s division: “As we had no supports upon our flanks, we were forced to retire.”18

Ironically, Lane’s brigade itself, dishing out all this punishment on Magilton’s two regiments, was in a precarious position. It could not stop other Federals—now clearly visible—sweeping beyond its right into the gap. Lane told Col. William Barbour of the 37th North Carolina to “hold his position as long as possible,” and so three companies were pulled back at a right angle to protect the flank. Worrying about being turned, the Tar Heels kept up an intense fire against several of the Pennsylvania regiments. Little did they realize that the isolated and unsupported Yankees would soon be in even worse trouble.19

But Lane’s regiments were surely in a tough spot. Unfortunately for the Tar Heels, the ground rose about fifty yards in front of the railroad, offering some protection for the 7th, 18th, and 33rd North Carolina but also preventing them from seeing any Federals advancing toward the lines. In the open and flat ground on Lane’s right flank, the 28th and 37th North Carolina were vulnerable to artillery and small arms fire from several directions. These regiments would nearly exhaust their ammunition dealing with the threat to their flank.20

Yet more Federals were heading their way as Gibbon’s brigades at last moved forward to support the Pennsylvania Reserves. Gibbon’s baptismal experience leading a division was going to be rough. He had graduated from West Point in Burnside’s class and later served in the Mexican and Seminole wars. A captain of artillery at the beginning of the war, he had quickly risen to the rank of brigadier general. Gibbon had ignored seniority in selecting brigade commanders and thereby ruffled several colonels’ feathers. His oft-expressed contempt for volunteer officers and his exacting inspections hardly made him a favorite. Yet Gibbon was a fine soldier of unquestioned courage and seemed well suited to work in tandem with Meade.21

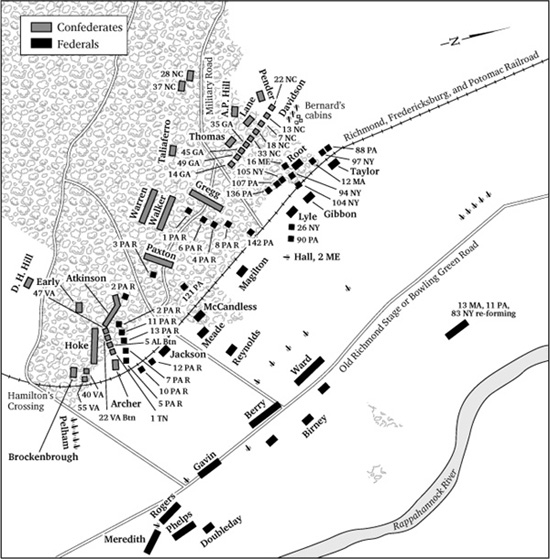

The Confederates stop Meade’s and Gibbon’s attacks, December 13, 1:00–2:00 P.M.

Gibbon’s troops had been up before dawn. In the early morning fog the men had stretched their stiff limbs and begun cursing even before breakfast. They had strolled about camp trying to get warm, gulping down hot coffee. After crossing the Richmond Stage Road, they had come under fire along the gently rising ground. They had lain in the mud, anxious to go forward as the cannon fire slackened around 1:00 P.M. Just as Meade’s men were moving out, Brig. Gen. Nelson Taylor proposed a bayonet charge toward Lane’s position. Gibbon said this would violate orders, and so the advance stalled for another half-hour. Meade later testified that Gibbon’s officers failed to charge the enemy lines quickly enough, so perhaps the recent shake-up in brigade commands had yielded its poisonous fruit.22

In any case, by 1:30 P.M. Taylor’s brigade had begun its advance under cover of rapid shellfire from two batteries Gibbon had ordered forward to within 200 yards of the woods. A recent Harvard law school graduate and Democratic politician, with his full beard Taylor nevertheless looked like the beau ideal of a Civil War general. Unfortunately his troops were already shaky. During the artillery barrage, when the 88th Pennsylvania on the brigade’s right flank had moved forward to elevated ground, scores of men had abandoned the ranks and run suddenly to the rear in complete disarray. Only after one of Taylor’s staff officers and a few of the regiment’s own officers had stopped this “disgraceful and causeless retrograde movement” did these soldiers rejoin the brigade line.23

Ironically, however, during the attack itself these same Pennsylvanians, who along with the 97th New York enjoyed the advantage at least of being protected by the same small rise that shielded three of Lane’s regiments, proved more stalwart than the outfits on Taylor’s left wing. This was hardly surprising. The 11th Pennsylvania and 83rd New York had to advance over open ground under blistering fire from the 28th and 37th North Carolina. Three times the 11th Pennsylvania’s colors drooped toward the ground. More than a third of its men, including its colonel, were hit in no more than thirty minutes of fighting. Casualties among the New Yorkers, including several officers felled by sharpshooters in the trees, matched those of the Pennsylvanians.24 Here was a typical Union tale of Fredericksburg: two regiments blown off the field and two more pinned down and taking casualties.

When Gibbon ordered Col. Peter Lyle’s brigade to join the attack, Taylor shifted the 88th Pennsylvania and 97th New York farther to the right to make room. Despite some uncertainty about Gibbon’s exact orders, the line of six regiments crept toward the railroad. This time some of the bluecoats managed to ascend the slight hill and pour a destructive fire into the 33rd North Carolina, but as the Yanks came over the rise, the Tar Heels returned the favor. Both sides ran short of ammunition, growing frantic as they exhausted the standard sixty rounds. Displaying more valor than judgment, one intrepid private sat on the railroad tracks coolly firing at Lyle’s men while an equally daring captain stood waving a cap to inspire his company. Lyle’s troops held their position for nearly half an hour, but after they expended nearly every bullet, the 90th Pennsylvania and 26th New York were forced to lie down.25

The attack sputtered to a halt. Even though his men had thus far failed even to cross the railroad and he risked committing the classic blunder of reinforcing failure, Gibbon decided to commit the rest of his troops to the assault. Around 1:45 P.M. he ordered Col. Adrian R. Root to bring up the First Brigade. With three regiments (107th Pennsylvania, 105th New York, and 16th Maine) leading and two regiments (94th and 104th New York) stacked behind the New Englanders, the troops moved smartly across a plowed field and through the shattered remnants of Taylor’s and Lyle’s brigades. Once they were under heavy artillery and rifle fire, their pace slowed to a crawl. Contrary to orders, many men halted to return fire. Root cobbled together a line from regiments that had held their ground during earlier assaults.26

Spearheading the attack, the 16th Maine advanced the farthest and suffered the most casualties in the division. Already reduced by exposure and hard marching to a mere 427 men, this rookie regiment acquitted itself well in its first big fight. After exchanging fire with Lane’s troops along the railroad, the men plunged ahead, driving a wedge between the 28th and 37th North Carolina. They encountered desperate resistance, vicious hand-to-hand combat with musket butts and bayonets. Out of ammunition, some of the Tar Heels hurled empty rifles—bayonets fixed—like harpoons. Not a few of the Maine soldiers seemed driven by a strange blood lust as they waded into the North Carolinians. One of them skewered a Rebel whom he accused of killing his brother. In the midst of this chaos Root’s brigade steadily gained ground. However, a deadly volley from the 33rd North Carolina, before it withdrew back into the woods, slowed the advance. On the left of Lane’s brigade the 7th and 18th North Carolina also pulled back at least fifty yards, and there the re-formed line held.27

To the left of the 16th Maine, the 105th New York and on their right the 12th Massachusetts advanced far enough to enter the woods and capture some prisoners. But like so many other outfits, they ran out of cartridges and received little support.28 On the heels of the 16th Maine, the 94th New York (with the 104th New York close behind) joined the bayonet charge against Lane’s position. Near the railroad, however, the New Yorkers became tangled up, and though they managed to enter the woods, they were soon stymied by confused orders. One company in the 104th lost more than a third of its men during this brief advance. “A battlefield is an awful scene,” one private told his home folks. “No tongue nor pen can fully describe the horrors.”29 On both flanks the regiments in Root’s makeshift line quickly became isolated. To the left the men of the 107th Pennsylvania had advanced enthusiastically but could not hold their position. Seven soldiers “showed the white feather,” the adjutant later admitted; this regiment, too, lost nearly a third of its strength in casualties. Still further to the left, the 136th Pennsylvania found itself alone in the woods running out of ammunition. On the brigade’s far right the 88th Pennsylvania charged against Lane’s flank but was left behind as other regiments withdrew across the railroad.30

Coordinating Gibbon’s advance with Meade’s attack had failed. Gibbon’s division had forced Lane’s men back in fierce but uneven and disorganized attacks. The movement into the woods had soon degenerated into bloody and chaotic small-unit actions that accomplished little aside from amassing casualties. To be sure, some of Meade’s men had poured through the gap in the Confederate line, and Gibbon’s troops had made some progress against the North Carolinians, but unsupported, these positions could not be held or initial success exploited.31

* * *

Ironically, several Confederate regiments faced similar problems defending their weakened lines and launching counterattacks. Col. John M. Brockenbrough moved his brigade to the left in response to Archer’s desperate pleas. The 47th Virginia and 22nd Virginia Battalion bolstered the embattled 1st Tennessee and 5th Alabama Battalion still desperately holding out against the Federal onslaught that had shattered Archer’s left. Closing to within sixty yards of the Federals, the Virginians drove the Yankees back toward the railroad (“an enfilading fire that swept us down with murderous accuracy and compelled us to retire,” wrote a Pennsylvania colonel), but Brockenbrough’s other two regiments—the 40th and 55th Virginia—fell behind in the woods.32

Fortunately for Archer’s forces, however, more help was on the way. Posted behind Walker’s guns and Brockenbrough’s infantry in thick woods, Early’s division had seen little of the fighting. A messenger from Archer pleaded for reinforcements just as an order came from Jackson to hold the division in readiness to move toward the railroad near Hamilton’s Crossing. Despite his gray hair and rheumatic body, the irascible and profane Early was an aggressive and able general. He hesitated but slightly. Word arriving from an artillery officer that large numbers of Yankees had swept into the “awful gulf” between Lane and Archer dispelled any indecision. It took a bold (or foolhardy) man to ignore a direct order from Stonewall Jackson, but about 1:30 P.M. Early sent Col. Edward N. Atkinson’s Georgians off to rescue Archer.33

Five of the brigade’s six regiments—for some reason the 13th Georgia failed to move—advanced about 250 yards, rending the air with Rebel yells. Crashing into the Pennsylvanians who had been making things so hot for Archer, they pushed the Yankees back toward the railroad. Some Confederates charged with less élan than others. A strapping conscript in the 60th Georgia cowered behind a tree until Col. W. H. Stiles ordered him up. The man then fell backward shouting, “Lord receive my spirit.” “The Lord wouldn’t receive the spirit of such an infernal coward,” Stiles sputtered. At that the soldier leaped up yelling, “Ain’t I killed? The Lord be praised,” and dashed forward, musket in hand. His cheering comrades had by this time wound their way through the trees toward the railroad and the copse of woods on the other side. Their biggest problem now was exposure to a possible Federal counterattack. Although Atkinson’s men were hit by Union artillery as they emerged from the woods and neared the railroad, the Georgians did not stop.34

Early sent Col. James A. Walker’s brigade around Atkinson’s left to drive the Federals out of the gap and relieve the pressure on Lane’s North Carolinians. Passing through another Confederate brigade, Walker’s troops ran into remnants of Meade’s attacking force and pushed them back toward the railroad. “The Rebels and our men were all mixed up together,” wrote a member of the 1st Reserves. “I did not know whether I could even get out alive or not.” Untouched by enemy bullets, a private in the 142nd Pennsylvania got torn up by blackberry bushes in his haste to escape. Although Walker had routed the Yankees to his front, he also realized the danger to his left from a couple of Gibbon’s stray regiments that had remained on the other side of the tracks, so he halted his men and drew back the 13th Virginia to protect the flank.35

In fact, Hill’s lines remained vulnerable. Early therefore dispatched Col. Robert F. Hoke’s brigade to shore up Archer’s right. As some of Hoke’s troops passed through the remnants of Gregg’s South Carolinians, the mortally wounded Gregg, braced against a tree, waved them toward the enemy with his cap. The Federals continued to cheer, with more bravado than confidence, even as Hoke’s brigade drove them toward the railroad. “The yanks showed their backs,” one Georgian exulted.36

Meade was furious. His initially successful attack was faltering for lack of support. A ball passing through his slouch hat did not lessen his anger, most of which was directed toward Brig. Gen. David Birney, whose Third Corps division was supposed to be supporting the attack. A Philadelphia lawyer of sturdy abolitionist stock, Birney thus far sported a lackluster war record. At 11:20 on the morning of the attack, Brig. Gen. George Stoneman, commanding the Third Corps in Hooker’s Grand Division, ordered Birney to cross the Rappahannock. Subsequently Reynolds sent the division forward to help Meade. Several advance regiments, coming under heavy Confederate artillery fire, fell back to the Richmond Stage Road.37

Meade dispatched, by his reckoning, three separate pleas to Birney for assistance. It never came. The tangled command structure, especially the extra layer of bureaucracy created by the grand divisions, along with poor communications and timid generalship all contributed to the mess. Stone-man was Birney’s immediate superior, but Birney had been instructed to follow Reynolds’s orders, not Meade’s. He later claimed that he had thought Meade’s attack was “a mere feint, a diversion,” but his punctilio would cost precious lives.38

After two unanswered requests for assistance, Meade galloped to the rear, hell-bent on finding Birney. Meade tore into the hapless brigadier with a ferocity that nearly defied description. According to one lieutenant, Meade’s profanity “almost makes the stones creep.” Birney lamely claimed to be awaiting new orders from Franklin, but this explanation did nothing to ease the situation. “General, I assume the authority of ordering you up to the relief of my men,” Meade thundered. But even as the division advanced belatedly to assist the retreating Pennsylvanians, Meade continued to storm. Cornering Reynolds later in the afternoon, he exploded, “My God, General Reynolds, did they think my division could whip Lee’s whole army?”39

Meade harped on the matter for weeks after the battle. Franklin had not understood the importance of the attack, he thought, but obviously neither had Reynolds. “The slightest straw would have kept the tide in our favor,” Meade told his wife. Personal loss exacerbated Meade’s distress. His beloved aide Arthur Dehon had been shot through the heart as he delivered instructions to Feger Jackson shortly before Jackson himself fell mortally wounded.40

The usually sterile official reports barely concealed the anger of Meade’s men. “I cannot close,” Col. Robert Anderson of the 9th Reserves wrote, “without expressing the conviction that had we been promptly supported, that portion of the field gained by the valor of our troops could and would have been held against any force that the enemy would have been able to throw against us.” This assertion ignored both the difficulty of winning any decisive advantage in wooded terrain and the inherent strength of Stonewall Jackson’s lines, but it quickly became an article of faith among many Federals and even some Confederates. Similar might-have-beens also appeared in letters to small-town newspapers, and later conversations with Rebel officers reinforced the Federals’ conviction that a well-coordinated attack could have carried the position and won the day.41

Persistent recriminations and Meade’s fulminations aside, the real issue and the genuine tragedy was, of course, the casualties. “You can hardly call it a battel it was more like a Butcher Shop then any thing els,” a badly shaken color-bearer from the 7th Reserves told his father. By the time Meade’s men had recrossed the railroad and reached comparative safety, the killed, wounded, or missing numbered at least a third of the division. Ten of the fifteen regiments suffered more than 100 casualties. Hardest hit was the 13th Reserves: it lost 161 soldiers in two hours of fighting. The gross statistics did not concern most soldiers. Their world revolved around their company, the boys with whom they had marched, laughed, griped, suffered, and fought. A private in Company G of the devastated 11th Reserves discovered that 24 of 30 men in his outfit had been wounded; a sergeant in Company C of the 142nd Pennsylvania noted that there were only 36 men left of the 60 who had entered the fray.42

“The sights are too horrible to describe with pen and ink,” this same sergeant informed his parents. “We were mowed down like grass upon the field.” The men in his company could only hope that Fredericksburg “may have been the first and last fight.” A busy surgeon confirmed that many of the dead and wounded had been left in the woods. For days missing men wandered back to their regiments. The grumbling, cursing survivors saved their choicest words for the inept generals who had sent them into such a fight without proper support.43 Yet for all Burnside knew, his left wing was driving the Confederates. The battle plan appeared to be working, and now it was time to hit the Rebels’ other flank.