14 Attack

I approve of all methods of attacking provided they are directed at the point where the enemy’s army is weakest and where the terrain favors them the least.

—Frederick the Great

The telegrams from James Hardie were terse but encouraging.

9:00 A.M.: “General Meade just moved out.... Skirmishers, however, heavily engaged at once with enemy skirmishers.”

11:00 A.M.: “Meade advanced half a mile and holds on.... No loss so far of great importance.”

Noon: “Birney’s division is now getting into position.... Reynolds will order Meade to advance.”

At his Phillips House headquarters Burnside read these dispatches intently. Though ensconced on the second floor with a powerful spyglass, he could not see much of Fredericksburg through the morning fog and much less to the south, where Franklin’s troops were fighting. Burnside in fact remained befogged in several other senses. He placed too much faith in cryptic information from Franklin, grasping at any sign of progress on the left so as to set the rest of his battle plan in motion. Unable to see most of the battlefield, he would have to rely on judgment and instinct to decide if and when to order an assault against the Confederate center on Marye’s Heights. Ideally his mind needed to be clear and well rested, but the loss of sleep was catching up with him. An aide later claimed he found Burnside napping at midday in the attic of the Phillips House. Whatever the truth of that story (and the source is not entirely reliable), on this morning Burnside was not in the best condition to launch a risky attack against the strongest part of the Confederate line.1

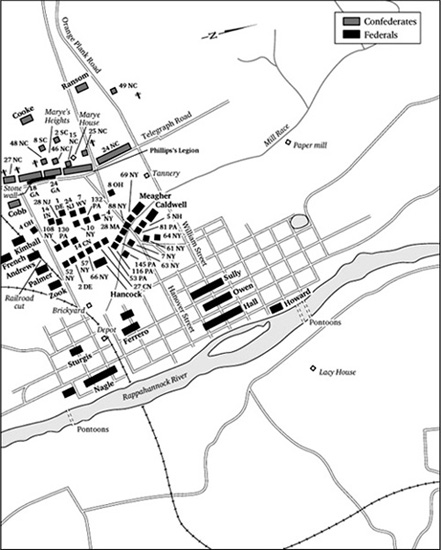

Geography exerted an even more decisive influence on the Union right than it had on the left. Buildings offered some protection while concealing Federal strength from Lee, but once ordered to attack, the troops would have to leave this relatively safe haven and advance over mostly open ground. Two main roads ran west toward Marye’s Heights. To the south, the Telegraph Road extended out from Hanover Street; at the edge of town it veered slightly southward before curling around the base of Marye’s Heights. In an elongated triangle formed as the Telegraph Road diverged from the extension of Hanover Street were houses and gardens that would slow an attacking force but would offer limited cover. The Orange Plank Road (an extension of William Street) also ran west from Fredericksburg; it skirted a brick tannery and crossed Marye’s Heights before heading toward Chancellorsville.

Just past the outskirts of town, more than a quarter-mile from Marye’s Heights, the Federals would encounter a millrace across their line of march. This offshoot of a canal running from the Rappahannock to a basin on the northern edge of Fredericksburg was about five feet deep and fifteen feet wide. Only three bridges spanned the ditch, however, and one of those had been stripped of timber, leaving only the stringers. On December 12 Federal engineers had partially drained the millrace, though no one seemed to have considered it much of an obstacle. The ditch’s steep bank on the far side would offer troops protection and an opportunity to reform lines. But beyond it, between the sheltering bank and Marye’s Heights, lay 500 yards of mostly open ground with only a few buildings, fences, and a slight swale providing any cover. Not only could Confederate artillery sweep this area, but unknown to Burnside and his generals, the Telegraph Road became a sunken road as it wound along the base of Marye’s Heights. The stone fences along each side could readily conceal a brigade or more of infantry.2

The stone wall on the Fredericksburg side stood about four feet high, and the Confederates had banked up earth against its face and to the south had hastily thrown up a few log breastworks and abattis. “What a place for infantry,” a young officer in the Washington Artillery exclaimed. But the real strength of the position was Marye’s Heights and the hills behind, from which shot and shell could be hurled against an attacking force. Rising sharply some forty feet above the Sunken Road and stone wall, Marye’s Heights commanded both the Plank and Telegraph roads as they emerged from town.3

Stone wall at the base of Marye’s Heights (United States Army Military History Institute)

Although neither army had yet learned the value of field entrenchments, Longstreet had improved a naturally strong position. To the left of the stone wall between the Telegraph and Plank roads, the 24th North Carolina of Ransom’s Division held a recently dug shelter trench. Nine guns from the Washington Artillery were posted in newly constructed gun emplacements near the crest, with seven more pieces on either side of this position to concentrate additional fire on the approaches to Marye’s Heights. Twenty-one guns on Telegraph Hill pointed toward both the Telegraph Road and an unfinished railroad cut to the south of the stone wall that guarded a potentially vulnerable flank.4

Besides the 24th North Carolina on the left, three regiments from Cobb’s brigade crouched along the stone wall. Brig. Gen. John Roger Cooke’s brigade (Ransom’s Division) stood about 200 yards behind Marye’s Heights, and Ransom’s own brigade lay within easy supporting distance. To the right, the rest of McLaws’s Division continued to hold the area south of Hazel Run, while Anderson anchored the left flank.5

Riding to Lee’s headquarters in the early morning fog, Longstreet could hear Union officers barking out commands across the way. To an artillery sergeant, the general appeared lost in thought as he surveyed the ground, speaking little, and then only in low tones. Still expecting the main Union attack to be against the Confederate right, Longstreet ordered Hood, with Pickett in support, to hit the flank of any Federal force that moved against Jackson. By 9:00 A.M. Alexander could glimpse the outlines of Stafford Heights through the fog, and an hour later he could see the open ground behind Fredericksburg. Soon his careful defensive preparations would begin to pay off. After conferring with Lee and ribbing Jackson, Longstreet had a few artillery rounds lobbed into Fredericksburg to test the range. Some time after 11:00 A.M. (likely closer to noon) his guns opened on the streets and bridges. The purpose was to create a “diversion” to relieve the pressure on Jackson. With uncanny timing these shots screamed toward Sumner’s men just as they were preparing to attack.6

At 6:00 A.M. Burnside had sent new orders instructing Sumner to “push a column of a division or more along the Plank and Telegraph roads, with a view to seizing the heights in the rear of the town. The latter movement should be well covered by skirmishers so as to keep its line of retreat open.” Like the orders to Franklin, these directions also could be interpreted (or misinterpreted) in several ways, but Burnside promised to visit Sumner later. Timing was critical. If Franklin’s troops made progress, forcing Lee to weaken his left, an attack by Sumner might just work.7

Burnside’s decision—as he later admitted—assumed that by 11:00 A.M. Franklin had already launched an assault on the Confederate left. But Meade would not actually cross the railroad for another two hours. Burnside did not yet realize that what were supposed to be coordinated attacks would be anything but. Another logical, though faulty, premise of the plan assumed that the ongoing attack on the Rebel right would compel Lee to send reinforcements from Longstreet to Jackson. In fact Lee had not weakened this sector one iota. Burnside’s thinking was not, as Baldy Smith later claimed, an “insolvable mystery,” but if the success of a military engagement depends, as Clausewitz observed, on the commander’s ability to “fight at the right place and right time,” the chances for success were slim.8

Sumner conveyed Burnside’s orders to Second Corps commander Darius N. Couch, who remained cool to the entire battle plan but whose troops would do much of the fighting. Couch selected French’s division to lead the attack, supported by Hancock’s division, with Howard’s division guarding the upper part of Fredericksburg against a possible Confederate incursion there. Receiving Couch’s orders at 9:30 A.M., French marched his brigades through the streets partially under cover of the morning fog.9

A graduate of West Point (class of 1837, which included such luminaries as Hooker, Early, John Sedgwick, Braxton Bragg, and John C. Pemberton), William H. French was a veteran artillery officer who had fought in the Seminole and Mexican wars. He had recently been promoted to major general after serving as a brigade commander during the Peninsula campaign and leading a division at Antietam. Maybe Couch’s skepticism about Burnside’s plans had filtered down to his subordinate because French’s official report precisely detailed the nature and timing of various orders, as if he were justifying his own actions while expressing no faith in the operation itself. Described as “imperious and impatient,” French elicited both obedience and hard work from his staff. French later stated privately that he had not reconnoitered the ground and that on December 13 he had protested launching the attack. In any event, he was not enthusiastic about his present task.10

As noon approached, French’s troops moved through the streets toward the Plank and Telegraph roads just as the Confederate artillery began firing into Fredericksburg. The early morning orders issued to the commander of the Washington Artillery on Marye’s Heights had been precise: “As soon as the enemy’s infantry comes in range of your long-range guns General Long-street wishes you to open upon them with effect. Be particular in acquiring the bearing and range of the streets of the town. The enemy passing through them will give you an opportunity to rake him, which you will of course take.” Confederate artillerists would long remember the “magnificent sight” of the blue lines snaking through the streets of Fredericksburg even as they prepared to unleash the fury of their guns.11

French’s men, who had spent the early morning hours reading mail, could hardly have anticipated the firestorm. Indeed, General Couch had to order some brazen souls to discard their recent plunder before going into battle. Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball’s brigade emerged from town first with an unusually heavy line (“cloud”) of 700 skirmishers from two Ohio regiments and one Delaware unit.12 Their orders were to drive off Confederate skirmishers, keep at their heels, and follow them into the Rebel breastworks.13 As the first troops approached the millrace, the scattered Confederate artillery fire exploded into a concentrated barrage. Guns on Stansbury’s Hill, Marye’s Heights, and Telegraph Hill rained fire onto the Federal skirmishers and the three brigades following them. The shells burst “beautifully” among the bluecoats, an English observer commented. The gunners could hardly miss such easy targets. “Set ’em up again,” one gunner in the Washington Artillery jeered as the solid shots bowled over Federals like ninepins.14

Yet as Longstreet and Col. James B. Walton of the Washington Artillery both noted with amazement, French’s men kept pressing forward, even as the intense fire shattered formations. Before deploying his 8th Ohio as skirmishers, Col. Franklin Sawyer had spied fences as well as scattered shops and buildings farther out Hanover Street. These, along with the millrace, could slow the advance but also offer protection, and they soon became welcome havens for men and officers alike. Artillery fire began raking the Buck-eyes even as they moved out at the double-quick and neared the millrace. At the head of the column some twenty officers and men fell almost instantly. Confederates described “gaps” torn in the Federal lines or “lanes ploughed out of human bodies.”

French’s and Hancock’s assaults against the Confederate left, December 13, noon–1:00 P.M.

Still the bluecoats drove the few Rebels from the ditch, scrambled across the small bridge, and re-formed their line under the protection of the western bank. Unsure what had happened to the other two regiments of skirmishers, Sawyer led his troops forward, but progress was halting as men paused to tear down fences. Mounting casualties—enfilading fire from the right was especially deadly—forced soldiers to crouch behind fences near the few buildings standing between them and the last 100 yards of open ground leading to the stone wall. Several men broke down the door of a small grocery near where the Telegraph Road and Orange Turnpike diverged. Carrying wounded comrades inside, they found a woman—likely the owner’s wife—hidden in the cellar. Under heavy fire they dragged her out to show them the well. By this time nearly a fifth of this small regiment had been killed or wounded.15

The other skirmishers fared no better. Both the 4th Ohio and 1st Delaware marched to the railroad depot; they turned there to cross the millrace, but a murderous fire dropped nearly a score of Buckeyes and several of the Delaware men. Remnants of both regiments somehow survived the artillery and advanced another 300 yards or so to reach the swale in front of the stone wall. Col. John S. Mason of the 4th Ohio issued the wildly unnecessary order for the skirmishers to lie down as Cobb’s musketry drove them to the ground. This proved to be a very unlucky place, especially for Henry A. Darlington, a twenty-five-year-old printer and volunteer fireman from West Chester, Pennsylvania, who had joined the 1st Delaware as a sergeant. Recently promoted to second lieutenant, Darlington fell wounded, and as several comrades carried him from the field, a Confederate shell blew his body to pieces.16

The rest of Kimball’s brigade was supposed to exploit the skirmishers’ “success.” With a jaunty, if jarring, “Cheer up, my hearties, cheer up! This is something we must get used to!” Kimball dispatched his four remaining regiments. They, too, crossed the millrace near the depot and then tried to move into line for the attack. More tightly packed, they suffered horribly from the artillery storm. Parts of the brigade reached the swale some 100 yards from the stone wall and even moved somewhat beyond but were stopped by what many bluecoats would later call a veritable sheet of flame, as Cobb’s infantry rose and fired a withering volley into their ranks. In addition, the Washington Artillery was pouring in canister. The Yankees tried to advance across the mucky, uneven ground and through the fences, but once they got to the swale, their depleted ranks had no hope of reaching the stone wall. About this time Kimball received a serious thigh wound and was carried off the field; Mason assumed command. “The brigade was scattered all over the line no regiment entire,” the Ohioan later wrote.17

The details of the engagement remain sketchy. “Shattered, torn and bleeding, our column still pushed—gained the open ground—drew up in line of battle and with bayonets fixed, rushed forward to the charge,” an imaginative lieutenant in the 14th Indiana informed his hometown newspaper. This recital could apply to any number of Civil War engagements. The regiment’s commander, Maj. Elijah H. C. Cavins, offered few details in either a letter to his wife or his official report. Other soldiers also stuck to general accounts of the fight.18 These Hoosier veterans hesitated to recount their searing experience in any detail. Many of the Union regimental after-action reports for Fredericksburg were similarly terse. No one wanted to dwell on failure. Cavins’s men did not shy away from reporting the casualties—after all, three brave color-bearers had fallen in a brief period—but they did not focus on how the casualties had occurred or say much about the fighting itself. In fact, it was an officer from another regiment, Colonel Sawyer of the 8th Ohio, who later penned the most graphic account of a young Hoosier who hid behind a stump trying to pick off Rebel gunners until both stump and man were blown to pieces by a Confederate shell.19

In the center of Kimball’s line two rookie New Jersey regiments each suffered more than twice the casualties of the 14th Indiana. That morning the nine-month volunteers of the 24th New Jersey had tried to hide their nervousness with imitations of whizzing shells, jokes, and desultory reading; two sergeants had even fought a mock duel with swords. What the regiment encountered beyond the town was no laughing matter: “screeching” artillery rounds that quickly increased the number of dead and wounded. Some men fell to the ground too terrified to move; others desperately begged God to deliver them. Most finally reached the swale, pressing themselves against the ground and awkwardly trying to load their weapons.20 No longer functioning as regiments or even as companies, the survivors simply fought to save their own lives. “This batel Was the grates Slaughter or the Most Masterley pease of Bootchery that has hapend during the Ware,” one of them wrote with raw eloquence. “I have ben in one fight and I think it Will be the last for is the most horiabel place . . . amounted to Nothing except to slaughter the solgers for nothing.”21

As Colonel Mason observed, the advance under intense artillery fire had so exhausted most of Kimball’s men that they had to pause at the swale, out of both the energy and the support to go farther. Kimball later guessed that a fourth of the brigade fell during the attack. A member of the 28th New Jersey marveled, “it is a greate wonder that it [the charge] dident kill us all.”22

Behind the stone wall the Confederates had been more than ready. Admonished to withdraw if Anderson’s Division on the left had to give way, Cobb had scoffed, “If they wait for me to fall back, they will wait a long time.” This statement summed up the man. Cobb had been a hardworking, scholarly lawyer and ardent secessionist back in Georgia. Though bitterly disappointed that his brother Howell had not been elected Confederate president, the pious Tom Cobb scorned anyone who wavered in his commitment to the southern cause. Despite his lack of military experience, he had become a capable general and rapidly won the respect of Lee and others. On the morning of December 13 Cobb had solemnly warned his troops about the bloody work ahead but promised to remain with them until the end. He would keep his word.23

As Kimball’s troops began advancing, General Ransom moved Cooke’s brigade up to the crest of Marye’s Heights and Willis’s Hill. A few Georgians behind the stone wall had nervously begun firing. Cobb, stalking up and down the Sunken Road, reassured his anxious troops, ordering them to wait until “you [can] count the Yankee buttons.” As Kimball’s shot-up regiments finally reached the swale, the Georgians, under orders to aim low, loosed “a perfect sheet of flame . . . from behind the stone wall.” These or similar words would be used countless times by the survivors on both sides. With double-shotted canister from Marye’s Heights also ripping into the Federals, a Georgia hospital steward coined another soon-to-be-familiar phrase describing the area in front of the stone wall as a “complete slaughter pen.”24

Through the smoke the Yankees could barely see their destroyers. Yet still more bluecoats approached the killing ground. French’s other two brigades were supposed to follow Kimball at 150-yard intervals and overrun the Rebel line. But even before Col. John W. Andrews’s brigade received the order to advance, one of the regimental commanders, Col. John E. Bendix of the 10th New York, was struck in the face by a shell fragment. Andrews had only three regiments; one had already been sent forward with the skirmishers. Around noon this small brigade “marched steadily up the slope and took a position in Kimball’s rear.” But with the Federal “line” already torn to pieces, Andrews could only send his troops forward to fill in the gaps. So many officers were hit, including Andrews, that regiments often became formless, leaderless masses hugging the earth for protection. The 10th New York, for example, lost nine of eleven officers and had three different commanders in less than an hour. Lt. Col. John W. Marshall called the situation “temporary confusion,” a gross understatement. To survivors it seemed they had passed through a “storm” of metal, a death-dealing hail. Indeed, this analogy leaped often to mind and pen. One tall fellow in the 4th New York had pulled up his coat collar as if he were heading into a gale.25

Why did they keep going? This is the most difficult question posed about Fredericksburg and many other Civil War battles. Some men mechanically obeyed orders, others still burned with commitment to the Union cause, many fought for their comrades, and a few acted from motives that could not be easily or simply explained. Soldiers often had trouble articulating their combat reactions to their families or even to fellow soldiers or perhaps to themselves. If most were simply trapped between the demands of fear and duty, sheer inertia and the absence of acceptable alternatives kept them moving forward, often halfheartedly as the casualties mounted. This was not the kind of gallantry described in novels, but it was courage nonetheless.

Andrews’s troops and each subsequent brigade had also endured the disheartening sight of the wounded and dead from the previous assaults scattered through the streets and fields. The men of the 132nd Pennsylvania, who had been badly bloodied at Antietam and were short of officers, apparently balked at the sight of the carnage. At one point the regimental adjutant had to retrieve the bulk of the regiment when only one company had followed him toward the front. Alongside an unfinished railroad cut, Confederate artillery shells—largely from Telegraph Hill—found their mark, dismembering or simply blowing men into indistinguishable pulp. Defying orders, shirkers carried the wounded to the rear. Several mud-covered men, spattered by blood and pieces of flesh, fired blindly toward the stone wall. A few pressed beyond the swale but could not stand against the withering fire. “[We were] blown off our feet,” one private reported, “staggering as though against a mighty wind.”26

Col. Oliver H. Palmer’s brigade, the latest to pass the depot and head into Rebel artillery fire, encountered wounded men lying all about near the millrace; some already wore the pallor of death. One man with both legs shot off gamely tried to be encouraging: “Pass on boys. Don’t stop to look at me.” Delayed by enfilading fire for twenty minutes or longer, Palmer’s troops were slow to reinforce Kimball and Andrews. The survivors then approached what amounted to infantry hell, “worse than Antietam,” as many soldiers described it.

By this time some men had no heroic impulses left. A few officers in the 14th Connecticut reportedly feigned illness to avoid entering the fray, but enlisted men also looked to skedaddle with a wounded comrade. Yet most plodded forward; many wondered why the Federal artillery did not shell the Rebels. Scores of wounded and dying men entered their field of vision, and then a shell burst at the head of one company. Several men went down, one with his face shot away. A major in the 108th New York crawled over three board fences and was eventually hit by a ball that knocked off his cap and inflicted a painful though not especially dangerous scalp wound. A few minutes later a spent ball badly stung his leg. Remnants of companies dashed toward the stone wall, sometimes with cheers and shouts but always with the same fruitless results: just more killed and wounded to litter the field. Bullets caromed off cartridge boxes and canteens; shell fragments struck haversacks and blankets; both poked holes in hats and overcoats unless flesh stopped them. Deadly missiles seemed to swarm like wasps and struck men almost everywhere—most often in the thigh or arm but also in the parietal bone, the scrotum, or the knee. Three different soldiers stumbled over a Connecticut sergeant seriously wounded in the leg; finally the poor wretch managed to crawl into a hut with other casualties.27

“It seems as if our company and Regt were all gone,” a Connecticut soldier summed up the result of French’s assault. The words “shattered and broken” applied to every regiment. Officially the division casualties totaled a mind-numbing 1,160. The combination of artillery fire and concentrated rifle fire had mangled bodies almost beyond recognition. Several high-ranking officers had been wounded. Worse was the growing conviction that it had all been for nothing. “A perfect failure,” a Pennsylvania private grumbled. A member of the 108th New York doubted there had ever been any chance for success: “We might as well have tried to take hell.”28

A brief lull occurred as the last of French’s troops stalled. The Georgians behind the stone wall decided they had repulsed a mighty legion with ease. Perhaps they had, but the reinforcements Ransom and McLaws fed into the Sunken Road during the assault had also helped. The 27th North Carolina in Cooke’s brigade had scrambled down the crest—apparently without orders—to bolster Cobb’s right and was soon joined by the 46th North Carolina. Kershaw also dispatched two South Carolina regiments to meet the next wave of Yankees. Even as the infantry fire subsided, the artillery on both sides continued to pound away. Near his headquarters at the Stephens House, Cobb was suddenly struck in the thigh by a piece of shrapnel. A handkerchief proved a poor tourniquet. The femoral artery had been torn, and by the time the wounded man was carried to a hospital behind Marye’s Heights, he had already lost too much blood. In shock, Cobb fainted and soon died.29

The Georgians and Carolinians defending the Sunken Road had little time to mourn their fallen commander. More Yankees were pouring from the streets of Fredericksburg, led by the redoubtable Winfield Scott Hancock. Tall and stocky with brown-to-reddish hair, blue eyes, and a distinctive mustache and chin whiskers, Hancock exuded an air of steady confidence. Regardless of his dismay over the formidable Confederate defenses, he was expected to succeed where French had failed.30

“We had to march for a considerable distance by the flank through the streets of the town,” Hancock wrote, “all the time under a heavy fire, before we were enabled to deploy; and then, owing to obstacles—among them a mill-race—it was impossible to deploy, except by marching the whole length of each brigade by the flank in a line parallel to the enemy’s works, after we had crossed the mill-race by the bridge.” Hancock neglected to mention that the west bank of the millrace offered the troops considerable protection, but he hardly exaggerated the magnitude of the task before him. Whatever doubts he entertained, though, were private. He solemnly instructed his regimental commanders that the Confederate lines “must be carried at all hazards and at all costs.”

Col. Samuel K. Zook commanded the lead brigade. A capable soldier, though like Hancock sometimes crusty and generally skeptical of the battle plan, Zook led his six regiments along the railroad cut through a brickyard and into line. As they turned toward Marye’s Heights, a shell blew apart a poor fellow in the 57th New York, and a piece of skull temporarily knocked Cpl. Lawrence Floyd unconscious. Other men dodged bits of clothing and equipment. When another volunteer in the 57th was struck in the back, en-trails flew in several directions. “Then I began to see the horrors of war,” one young recruit informed his parents. It was not the only horror he saw. He also noticed a severed head lying on the ground and several men who had lost arms or legs. Amazingly, some of Zook’s men, after tearing away or clambering over fences under relentless fire, reached the remnants of French’s division, marked by flags planted 100 yards from the stone wall. Even though a third of the brigade had already been hit, some men drove beyond French’s lines. Elements of the 53rd Pennsylvania got to within perhaps 50 yards of the stone wall before taking shelter in a few buildings earlier held by French’s skirmishers. Once within range of Confederate infantry, one soldier noted, “the boys involuntarily pulled their hats down over their eyes as if breasting a storm.”31

So many officers fell so quickly that the command of regiments sometimes passed to two or three men in a matter of minutes. The after-action reports often implausibly described a steady advance and failed to capture the chaos of the effort. The experience of a private in the 27th Connecticut was typical. About halfway up the hill “the brigade got rather confused and different regiments were mingled together.” Fragments of companies gathered near the swale or behind fences or in buildings—wherever they could find some safety. The final casualty figures for Zook’s brigade were staggering: over 500 men were killed, wounded, or missing, and there would be at least 26 leg and 15 arm amputations. The 57th New York had only 50 men left after the battle.32

From any vantage point Confederate officers could easily see the results of their well-prepared defense. As Longstreet later remarked, “Every gun that we had in range opened upon the advancing columns and ploughed their ranks by a fire that would test the nerves of the bravest soldiers.” The Federals had moved out in “handsome style,” he marveled, but also noted that they “did not meet the fire of our infantry with any heart.” As before, Federal artillery rounds from Stafford Heights had little effect on the well-protected Confederate gunners who poured shot, shell, and canister into Hancock’s soldiers.

With Tom Cobb dead, Col. Robert McMillan of the 24th Georgia assumed command of the troops in the Sunken Road. Calmly moving along the lines, he ordered his infantry to hold their fire. The men opened with devastating effect once the Yankees came in range. Cobb’s regiments suffered only light casualties. Cooke and Ransom’s brigades took heavier losses, especially in the regiments that remained on Marye’s Heights under steady fire with little cover. The unfortunate 48th North Carolina, exposed to Federal artillery and stray infantry rounds most of the day, lost nearly 180 men.33 Yet this outfit and the hard-hit 15th and 25th North Carolina were very much the exceptions as Ransom’s and McLaws’s troops confidently stood their ground with more bluecoats heading their way.

Closely following Zook came the Irish Brigade, one of the hardest-fighting outfits in the Army of the Potomac. The unit’s battle flags had become so tattered that Brig. Gen. Thomas Francis Meagher had sent them back to New York. Because new ones did not arrive in time for the battle, Meagher ordered boxwood sprigs pinned to each man’s cap as a reminder of their proud heritage.34

One of the war’s great characters, Meagher had been born into a prosperous merchant family in Waterford, Ireland, where he early became a crusader for Irish independence. Arrested by British authorities and exiled to Tasmania, in 1852 he had turned up in California and eventually made his way to New York City. A self-promoter with the flair of P. T. Barnum and the charm of Aaron Burr, he had dabbled in law, but his real talent lay in oratory and politics. Raising troops for an Irish brigade of New Yorkers in the fall and winter of 1861, he had courted powerful leaders ranging from Governor E. D. Morgan to Archbishop John Hughes. In the fall of 1862 the 28th Massachusetts recruited in Boston and the 116th Pennsylvania from Philadelphia had joined Meagher’s three New York regiments.35

Because of hard marching and bloody combat, the Irish Brigade appeared downright puny on the eve of Fredericksburg. Most of the regiments could muster no more than 250 soldiers. The 28th Massachusetts was relatively robust with 416 men, but the 63rd New York brought to the field only 162 rifles. Meagher characteristically claimed that his boys had never been in “finer spirits.” This could well have been true of Meagher himself, a notorious drinker. On this day as on many others, controversy would dog Meagher, but he relished the limelight. His own troops were entranced by his natural charisma and respected his courage and leadership as well as his care for their creature comforts.36

Meagher, decked out in a dark green suit with black shoulder knots embroidered with silver stars and a yellow silk sash across his breast, had been up early on the morning of December 13 exhorting his men. A Rebel shell interrupted one of his speeches, and during its dramatic conclusion the “mangled remains—mere masses of bloody rags” from three members of the 69th New York were carried off. But nothing could stop the flow of Meagher’s words, or his tears. The soldiers must fight hard for their adopted land, he urged the 88th New York, because they were the regiment dearest to his beloved wife. As officers issued final instructions, the men appeared solemn. A Jesuit priest strolled among them blessing Catholics and Protestants alike. For a few moments each man was left alone with his thoughts. Even through the smoke and haze and the overwhelming smell of gunpowder they could anticipate what lay ahead. Rebel shells bursting in the streets and the terrible suspense were added to the sight of the wounded. A German soldier whose foot had been shot off nevertheless rode along in a wheelbarrow coolly smoking a cigar; an ashen-faced captain was carried atop a window shutter after having one leg nearly shot clean off. As this grotesque parade passed, a young Pennsylvanian about to enter his first battle fainted.37

When the 116th Pennsylvania trudged out Hanover Street, the men heard a cat mewing amidst all the racket. Solid shots caromed through the streets, and a shell crumbled a brick chimney. The Irish Brigade started taking casualties before it even emerged from the supposed shelter of the town. A Pennsylvania sergeant with his head blown off fell to his knees still grasping his rifle; a single shell left eighteen members of the 88th New York hors de combat. Soldiers could now see the ground where French’s and Zook’s troops had been slaughtered.38

Between 12:30 and 1:00 P.M. Meagher’s approximately 1,200 men crossed the dreaded millrace. Some used a rickety bridge; others scrambled over on the stringers; many, seizing the quickest way to the relative safety of the far bank, splashed through the shallow water. Sweating profusely, breathing heavily, their hearts pounding, soldiers threw themselves onto the ground and rested there for about ten minutes, waiting for orders. Having already been mauled by Rebel batteries (some men had fallen mortally wounded into the ditch), they now discarded blankets and haversacks. The “clink, clink, clink” of bayonets being fixed “made one’s blood run cold,” a private recalled. Officers’ whispered orders heightened the terror as thoughts turned to the awful test that surely lay ahead. Dead men from French’s division were strewn about them. One soldier had been hit by a solid shot, and his head, according to Pvt. William McCarter of the 116th Pennsylvania, now resembled a halved watermelon.39

“Irish Brigade, advance. Forward, double-quick, guide center.” The men could see the smoke of infantry fire to their front. Once again the Rebel artillery enfiladed the lines. Gaping holes opened in the ranks, then closed; colors fell and rose again; too many men were being hit; walking wounded stumbled to the rear. An orderly sergeant in the 116th Pennsylvania jerked around, a hole in his forehead, blood splashing as he fell at a young lieu-tenant’s feet. Forty percent of the men were hit before they had even fired a shot. So many officers and color-bearers went down that companies and regiments seemed to evaporate.

Somehow the survivors forced their way beyond French’s lines. How far would be disputed for years, but a few men apparently got to within twenty-five yards of the stone wall. They now fired at will, but the Confederate volleys were steadier and deadlier. “Blaze away and stand it boys!” shouted Maj. James Cavanagh of the 69th New York, but he, too, was soon badly wounded. “Our men were mowed down like grass before the scythe,” a member of the 88th New York wrote after the battle. The familiar description hardly did justice to this particular hell.

For the stranded Yankees near the wall, the whole affair had degenerated into small, bloody firefights. Some men took shelter near a brick house while others stacked pieces of wood fence into flimsy barricades. To Private McCarter it seemed that every second or third man along the line had been hit, and soon a bullet tore into his shoulder. He lay on the ground, still clasping his rifle, thinking the end had come. Praying quietly, he recalled feeling quite composed. But then a comrade fell by his side with a horrible stomach wound. “Oh, my mother,” he gasped, twitched for a few seconds, and died. Meanwhile other soldiers still cursed and fired toward the Rebels; running out of cartridges, they grabbed more from the dead and wounded. The bodies of the fallen provided some protection for the intrepid souls who advanced beyond the swale out into the open ground.

Remnants of a few companies scrambled over the third and last wooden fence, but this impotent assault sputtered with hardly enough officers left to lead a disorganized retreat. Not only had entire regiments been smashed up in little more than thirty minutes, but to the commander of the 28th Massachusetts it seemed that the brigade was simply gone. For the survivors who bemoaned the absence of artillery or infantry support, the terrible casualties represented a blood sacrifice to military incompetence.40

Confederates behind the stone wall might well have agreed with their enemies. Some men had fired so many rounds that their rifles had become fouled and their faces as sooty as blackface minstrels. Each time the blue columns inched forward, the “crackle” of Confederate rifles, according to one witness, sounded “like a thousand packs of Chinese crackers.” Ironically many of the men so efficiently slaughtering the Irish Brigade were Irish too, including their commander, Colonel McMillan, who enjoined his troops, “Give it to them now, boys! Now’s the time! Give it to them!” Yet under such circumstances compassion for enemies seemed natural. “Oh God, what a pity! Here comes Meagher’s fellows,” one Rebel cried as he spied the evergreen sprigs. Confederates observing this charge knew courage when they saw it, and now their brave foes lay bleeding and dying on ground that had once yielded corn for shipment to the starving in Ireland.41

Such ironies hardly mattered to Meagher’s men as they lay on the ground expecting any minute to be blown up by a shell or picked off by a sharpshooter. And these scattered soldiers were the lucky ones. Three of five regimental commanders already had been hit; some line officers had been struck several times. It would be days before anyone would know how many were missing and likely dead. Were there even 250 men left in the brigade? It seemed so pitifully depleted that a corporal in the 28th Massachusetts assured his wife that the “rest of the fighting will have to be done without our aid.”42

None of this carnage, however, prevented Hancock from sending in his last brigade. Brig. Gen. John C. Caldwell had been a teacher and farmer back in Vermont. Slow moving, stocky, easygoing, and occasionally lazy, he was a solid though unspectacular volunteer officer. Under galling artillery fire his sizable brigade of six regiments (nearly 2,000 men) moved through the streets dodging falling debris. To relieve the tension, Col. Robert Nugent, who commanded the 69th New York in the Irish Brigade, advised Col. Robert E. Cross of the 5th New Hampshire to make dinner reservations for them at the Spotswood House once he reached Richmond. Cross, already suffering from fever and chills, replied with a string of profanity.43

Caldwell pushed his men forward until they stumbled onto a cluster of troops firing ineffectually toward the Rebels. Some of Caldwell’s soldiers on the left began popping away despite orders against firing before they had penetrated the Confederate lines. The general himself had to walk the brigade line to prod the men into motion again. On the right the 5th New Hampshire and 81st Pennsylvania advanced beyond the Stratton House, a two-story Greek Revival structure owned by a local wheelwright. The 5th New Hampshire, with two commanders already hit, now found its progress stymied by groups of men from the previous attacks firing wildly toward the Confederates. The surviving officers on that end of the line (the 81st Pennsylvania had four different commanders in a matter of minutes) simply could not form a battle line (“human valor had its limit,” a young private decided). The few Granite Staters who managed to crawl over or slither through the last board fence likely came as close to the stone wall as any other Federals that day. But most men had been mowed down, and the regimental colors had fallen five or six times.44

The brigade line—earlier it had reminded a lieutenant in the 64th New York of martial scenes described in schoolbooks—fell apart. Toward the center the largely German 7th New York moved beyond two groups of men from earlier charges who had been pinned down. To its immediate left the fresh recruits of the 145th Pennsylvania had been hit by enfilading battery fire before crossing the millrace. The men advanced unsteadily over the muddy ground. With the left wing of the regiment cut off by a high board fence, the right began giving ground, slowly at first, then precipitously. Caldwell admitted that the regiment “broke and fell back.” Even Hancock’s report, which lavished praise on nearly every regiment and every officer, contained a hint of censure. Col. David B. McCreary, however, testily denied that his boys had skedaddled. Few soldiers commented on the hasty retreat, though one man blamed a German regiment in front of them—perhaps the 7th New York—for any confusion. Whatever the explanation, the Pennsylvanians stood under fire long enough to lose nearly half their number and for the regimental flag to receive fifteen holes.45

Even veterans had trouble advancing, a sergeant admitted. Col. Nelson Miles took a bullet in the throat as he tried to push the 61st and 64th New York beyond a wooden fence. Despite his departure from the field and the panicky withdrawal of the 145th Pennsylvania, the New Yorkers held their position and fired only when ordered but could not move beyond the sheltering fence.46 Caldwell’s men had been no more able than Zook’s or Meagher’s troops to keep going. This charge, like the previous ones, never seriously threatened the Confederate position.

A staff officer who claimed that half the brigade had been hit exaggerated only slightly. The stalwart 5th New Hampshire, 7th New York, and 81st Pennsylvania had lost nearly two-thirds of their strength, and even the shaky 145th Pennsylvania had suffered more than 200 casualties. Overall, Hancock estimated his losses at around 40 percent, including some 150 officers. Besides wounded commanding officers, the heavy toll among the staff officers and horses thwarted efforts to coordinate the attacks. Hancock himself almost became a casualty; a bullet pierced his coat and grazed his abdomen. “It was lucky I hadn’t a full dinner,” he remarked. A New York surgeon in Caldwell’s brigade, contemplating the shuffling of command structure caused by the carnage, observed that “these changes admonish us that life is uncertain here and military rank or position subject to continued change.”47

A common measure of Yankee valor on December 13 and for years thereafter was proximity to the stone wall. Despite the general assumption that Hancock’s men came the closest, rival claims and sketchy reports have produced confusion and mild controversy. Perhaps some Federal lay dead only fifteen or twenty paces away, as several sources, including Confederate ones, suggested. Some contemporary evidence placed the 53rd Pennsylvania from Zook’s brigade nearest the stone wall, but the 69th New York, the 88th New York, and the 116th Pennsylvania in the Irish Brigade have had their champions. What about the horribly bloodied 5th New Hampshire in Caldwell’s brigade? Does it matter? Not much perhaps, but General Sumner recognized the uncommon valor of many regiments and later informed a group of congressmen who had never been close to a battle, “No troops could stand such a fire as that.”48

Throughout the afternoon, men from French’s and Hancock’s divisions straggled back toward town. Many more simply pressed themselves against the ground, perhaps unable to move. “I wondered while I lay there,” a young officer in the 57th New York later wrote, “how it all came about that these thousands of men in broad daylight were trying their best to kill each other.” He could find no more “romance” or “glorious pomp” in war, only bitter thoughts about the fools who had ordered his regiment onto this killing ground. Now they simply had to stay put, still under fire from the front and occasionally from the rear. Whenever the shots were flying especially thick, Colonel Cross of the 5th New Hampshire “covered [his] face and counted rapidly to one hundred.” If a man dared lift his head he could see fresh troops being shot down.49

Everyone, especially the wounded, was parched, but the Good Samaritan who tried to haul out a canteen to a thirsty soldier risked his life. Some men were hit repeatedly or watched as comrades were killed a few feet away. Soldiers wrapped themselves in blankets as if this might protect them against the leaden storm or even rolled dead bodies into macabre breastworks. Somehow they simply held on. “We might as well die here,” declared the colonel of the 53rd Pennsylvania, and without ammunition there was little else they could do. Literally immersed in the carnage, men expected to die.50

Toward late afternoon the survivors of both French’s and Hancock’s divisions were withdrawn from the field. In ones and twos, men arose from among their dead and wounded comrades. But given the breakdown in command, only parts of companies and regiments made it back into Fredericksburg. In the Irish Brigade, it was literally every man for himself as soldiers recrossed the millrace. But reaching town did not guarantee safety. Just as one group of the brigade’s soldiers neared the outskirts, a solid shot bounded down a street and mortally wounded a captain in the 63rd New York. He lived barely long enough for Chaplain William Corby to hear his confession. Thirsty troops drank water from gutters; with bowed heads they spoke gravely of fallen comrades. At dusk Fredericksburg seemed like a vast graveyard. “Sorrow hangs as a shroud over us all,” commented one New York private.51

The price paid for using conventional assault tactics against well-protected infantry and massed artillery had been staggering. Yet both armies had not yet recognized the importance of field entrenchments or the necessity of flanking strong positions. Whether the rifled musket was revolutionizing warfare is still being debated by historians. Only weeks before Fredericksburg, Old Brains Halleck maintained that smoothbores were equally if not more effective in a “close engagement.” As Pickett’s Charge and Cold Harbor would later demonstrate, adjusting tactics to the size of Civil War armies and increased firepower was a slow process.52 Given the thinking of the time, Burnside’s limited information about the fighting on the Federal left, the poor staff work, the absence of effective reconnaissance, and ignorance of the terrain west of town, it is understandable that French’s and Hancock’s troops had been ordered to attack the strongest part of the Confederate line. It is truly appalling, however, that fresh divisions continued to cross the same ground for several more hours.