22 Winter

Only absolute necessity and prospect of great advantages can excuse winter operations.

—Frederick the Great

Christmas was coming, but with the possibility of more fighting still hanging fire, few soldiers thought much about the holiday. Republican newspapers spurned any suggestion that the army go into winter quarters, and from Rhode Island to Wisconsin editors kept beating the drums for a new offensive. Europe required new evidence of northern determination, and in any case Greeley reported the troops itching for another go at the Rebels. Even conservative newspapers suggested alternate routes to Richmond and agreed that Burnside should try to capture the Rebel capital before spring.1

Yet those shouting the loudest would not have to put up with the hardships of a winter campaign, and so the Union soldiers scoffed at their advice. Lee’s men, too, would suffer because their government had not remedied serious supply problems. Somber reflection would thus taint Christmas in both armies as the holidays only widened the psychological gulf between soldiers and home folks. But for the time being, strategic questions also intruded.

As the weather turned colder, few soldiers showed much interest in campaigning. Rumors spread through the bivouacs that the army would, in fact, be going into winter quarters, that a corps or even a grand division was going to be withdrawn for garrison duty in Washington. But there had been no official word, and the troops wondered impatiently how long they would have to lie on the ground without tents. With perhaps the example of Napoleon’s Russian venture in mind, Col. Emory Upton of the 121st New York predicted that the army would lose 15,000 men to illness during a winter offensive.2

In some regiments the men had begun logging up tents and building huts only days after they had recrossed the Rappahannock. The sounds of axes, hatchets, and hammers cut through the crisp air, and within a week shanties dotted the landscape. That officers allowed men to log up their tents suggested the campaign was over, but uncertain of Burnside’s intentions, savvy veterans hung back, waiting until they were sure. Getting a good start on a hut and then suddenly having to move would be the ultimate frustration.3

The construction was hardly uniform. Camps sprouted with an assortment of architectural styles, with liberal use of Virginia mud being the only common denominator. Some soldiers dug several feet into the ground, while others erected more conventional cabins, though the term “shebang” perhaps best captured the ramshackle appearance of these dwellings.4 The dimensions were not even remotely standard.5 Some huts were a snug 6 feet by 6 feet; more commonly the shanties were about 100 square feet. A central ridgepole covered by fly tents rose 6 feet or higher in the center. They had no windows and smoky barrel chimneys, and sunlight seldom penetrated the gloomy interiors unless the “door,” usually an old piece of sack, was open. The most carefully constructed cabins were tight and warm, but more typically they were “dark, dirty, dismal, and cheerless.”6

Many soldiers, however, reserved such comments for their diaries or their comrades. Letters to family emphasized the cozy warmth of newly built “homes.” Word of a “snug little bed” doubtless eased one wife’s worries about her Hoosier husband freezing to death. A Massachusetts artillery captain waxed almost lyrical: “When I come in evenings, hang up my cap, put on my slippers and sit down in my easy chair in front of a big, blazing fire, I am nearly as comfortable as in a parlor at home.” He had not become a ruffian and instead maintained some semblance of civilized existence.7

The shanties at least provided shelter and a place to sleep. Soldiers fashioned beds from cracker boxes and barrel staves supported by sticks driven into the ground and covered with twigs or saplings. Hay, ticking filled with dry leaves, or pine boughs provided a modicum of comfort. Canteens and haversacks hung on pegs; a shelf over a fireplace held miscellaneous dinnerware; cracker boxes stored virtually everything else. Although cramped quarters bred both disease and despair, a New York lieutenant tried to accentuate the positive: “You could call the tent, fireplace, steps, floor, bed and all a clumsy heathenish affair—I call it the perfection of ingenuity, architecture, and engineering—and I find it more comfortable than a house.”8 Again the yearning for the familiar trappings of home helped men tolerate or even appreciate their crude surroundings.

Some fool knocking a chimney over or, worse, a fire quickly ended such reveries. Even without such mishaps, settling in for several months of stinging eyes and constant coughing intensified the misery. Clad in overcoat and gloves, Charles Haydon, a captain in the 2nd Michigan, squatted near a fire trying to avoid the smoke and wondering where all the heat had gone. He missed the conversations of friends and had grown tired of hearing bugles or drums or soldiers squabbling. Perhaps pining after old pleasures was a weakness, he conceded, but his misery also stoked “mingled hate, revenge, and a determination to uphold our cause to the last.”9

He could have been referring to the “last” stick of kindling because both armies were rapidly denuding the countryside. Finding enough firewood had become a challenge, especially when nearby trees served as windbreaks. With farmers’ fences and even outhouses falling under the axe, a division quartermaster predicted that “in another month we shall freeze as well as starve.”10 Chopping wood, tying it up in bundles, and dragging it back to camp became the most onerous of winter duties. According to one estimate, it took between 150 and 200 fires a day to keep a regiment warm and fed.11

The payoff for all the hard labor was a roaring fire to gather around at night. Soldiers huddled near the flames wrapped in whatever they could find. Many had shed their knapsacks and blankets before going into battle, and new blankets did not arrive immediately. The men had to line the notoriously thin army blankets with newspapers, but even then some soldiers slept in their clothes and used an overcoat for more cover.12

The Army of the Potomac was probably the best-equipped army in world history, but that fact was cold comfort—literally—to men convinced that they lacked decent clothes for the winter. “There is criminal negligence somewhere,” a New Jersey colonel informed his sister. With no fear of demagoguery, Democrats charged that corrupt contractors and foot-dragging by bureaucrats were killing brave soldiers in Virginia while the government provided clothing for idle slaves and unemployed British workers.13

The reality was more prosaic. Despite spot shortages, War Department shipments of pants and overcoats soon reached the camps. No one had frozen to death, Cpl. Peter Welsh of the Irish Brigade scoffed, nor had he seen any man without pants, though some boys looked pretty ragged. Other Federals reported adequate clothing supplies.14 The soldiers, of course, welcomed items from home, but shipping costs and delays gave pause to requests for boots or other bulky items. One New Hampshire recruit claimed his new gloves “fit like a duck’s foot in a mud puddle” and his shiny boots would help “stamp out the rebellion.” A member of the 24th Massachusetts reported that his regiment was “as fine a looking lot of soldiers as ever handled a musket or marched a mile.” But his point was tinged with political bitterness: “Uncle Sam ought to be proud to think that we had such a fine lot of fellows volunteer to fight, bleed, and almost die for the sake of a cussed nigger.”15

Everyone’s outlook would have been brighter with better food. As regiments settled into camps, regular supply had resumed, yet the monotony of salt pork and hardtack grated on the soldiers. “This is the way us poor cusses halfto live” one New Yorker informed his sister. The usual grumbling over meals now carried political overtones. Few privates doubted that commissary officers skimmed off supplies, but even worse, crooked contractors sent the army rancid bacon crawling with maggots. Such charges in the wake of another military disaster added to the growing conviction that folks at home would never understand what soldiers had to endure in the field.16

Disease remained the deadliest enemy. The general health of many regiments was reportedly poor, and in fact mortality rates from sickness in the northern armies jumped dramatically between November and December. Nightly coughing, groaning, moaning, and labored breathing bespoke the costs of a winter campaign. Sometimes it seemed the army had become one vast hospital. Soldiers pictured folks at home reading about daring troop movements, unaware of how many men were fighting much less dramatic but equally deadly battles against illness.17

By the end of the year, some regiments appeared woefully depleted. The 13th New Hampshire reported no more than 400 effectives, with at least 250 men answering sick call in the morning or already in a hospital. The 24th New Jersey, one of the first regiments to charge the stone wall, was almost as reduced from disease after the battle and soon had fewer than 300 men fit for duty. Other outfits reported comparably depressing numbers.18

Despite the cooler weather, diarrhea—“this terrible complaint of the army”—still plagued the troops. One surgeon blamed adulterated coffee and the shortage of vegetables, but whatever the cause, the number of cases held steady and the death toll climbed. Typhoid fever proved even more devastating. Young men who appeared perfectly healthy suddenly fell ill and died within days. Contaminated water and a poor diet explained the outbreaks, though even men who understood how and why the disease spread adopted an attitude of helpless inevitability. “Most of us have lost our courage and expectations of reaching home, or even dying on the battlefield—a fate less cruel than dying by inches,” reported a Maine volunteer.19

These deaths were a familiar occurrence in division hospitals. Complaints of general disarray—drafty hospital tents, patients sleeping on straw or using knapsacks for pillows, and food shortages—persisted even after many of the wounded had recovered or been shipped to Washington. A musician in the 24th Michigan with a bad cold decided to visit a nearby hospital. “One look was enough for me,” he gasped. “God forbid I should have to go there.”20

The sheer numbers of the dying were numbing, and like any statistics, they failed to capture the poignancy of individual cases. Cpl. Samuel W. George of the 12th New Hampshire had left a wife and eight-month-old twins back in Concord. Nearly six feet tall with black hair and a dark complexion, this once vigorous thirty-six-year-old had become seriously ill in December. He languished in camp during the fighting on December 13. Several days afterward, in the final moments of his life, he managed to raise himself in bed for one last look at pictures of his wife and children. Such deaths, at once heartrending and commonplace, seemed especially pitiable to surviving comrades who also felt so far from family and friends. Relentless reminders of mortality compounded the post-Fredericksburg gloom.21

Funerals also added to the woe. There were three burials on three consecutive days in the 122nd Pennsylvania and three in one day in the 108th New York. The sound of fifes or a noisy Irish wake carried the same doleful message. With no chaplain available to offer final consolation, a plainspoken member of the 124th New York stretched his arms toward the heavens and implored, “Great God of battle—as we bury poor Tom’s mangled body, let his soul enter Heaven—Amen!” Some men still wrote in the age’s euphemistic style about a soldier’s “last march” before “he is borne on Angel wings to join his God in glory,” but Walt Whitman better recaptured the mood in one camp near Falmouth during a perfunctory burial: “Death is nothing here.” Even a Maine nurse who fussed over patients sadly noted her own “indifference” as she closed the eyes, wrapped the face, and cut off a lock of hair from another dead soldier.22

The news of these deaths, usually conveyed in an officer’s letter, often reached a man’s home shortly after Christmas. Joseph Heisler had complained of rheumatism right before the battle, and by December 20 he had died of what was vaguely called “brain fever.” His brother, Cpl. Henry C. Heisler of the 48th Pennsylvania, had him buried in a rough box and erected a crude headboard so at least the grave would be marked if their father ever came for the body. “It was very hard,” Heisler wrote to a sister, “to see him die so sudden but here a man can be well and hearty one day and can die the next.”23

In the midst of death and its reminders, camp life went on; regimental routine distracted fears of what lay ahead. Reveille, doctor’s call, roll calls, meals, drill, dress parade, and taps continued day after day.24 Junior officers inspected tents, sinks, and cooking facilities; they supervised endless drilling. Captains filled out forms in triplicate and, if they were ambitious, boned up on military science. At the top, a good colonel who kept his men occupied and earned their respect often made the difference between a miserable, unhealthy camp and a clean, orderly one. Even then only a road-building detail, provost duty in Falmouth, or unloading supplies at Aquia Landing broke up the tedium.25

Fortunately the picket truce generally held, and shouting across the Rappahannock sometimes led to an exchange of visits and meals. The Rebels were the “same kind of people we are,” a New Yorker in Doubleday’s division remarked as if much surprised by this discovery. A Michigan volunteer considered each side equally “sick of this unhuman wholesale slaughter” and believed the rank and file of both armies would vote for peace. Perhaps so, but both men missed an important distinction. Although some sharp repartee still continued, even sociable Confederates sounded more confident if not cocky. A fellow could hear them across the river whistling and singing, and when they talked of the war ending by spring, they meant with southern independence secured.26

Occasional fraternization with the Rebels merely enlivened dull times. Repairing tents, writing letters, or gathering wood hardly filled the idle hours. “Cut off from civilization” became a common lament. “One never thinks in the m[ornin]’g how to enjoy himself during the day, but how to get through it without positive suffering,” wrote a Michigan officer. The hours passed sluggishly; a day sometimes seemed like an eternity. Peering from his tent across a “sea of red mud” or staring into the fire was driving a Massachusetts volunteer crazy. With nothing to do, he would “go to bed in sheer desperation then roll and toss all night.”27

Seeing the same grimy-faced soldiers and listening to stale old jokes around campfires grew tiresome, so the boys welcomed any momentary relief. Civilian visitors, especially if they were female, were the best distractions. To hear the “rustle of silk would be the sweetest music” to a New York lieutenant who, like men in any age and clime, longed for the “sight of a pretty face” and the “silvery tones” of a woman’s voice. Soldiers vividly recalled when they had last seen a woman and could describe in great detail any who ventured into camp, no matter how unpromising their appearance. Although laundresses seemed “amphibious creatures,” deprivation bred uncommon boldness. One adventurous private in the 17th Maine tried to kiss the rather large “Dutch Mary” and got a hard whack with a wet shirt. Enterprising, well-dressed prostitutes ventured near the bivouacs and presumably made a living. Officers, however, worried more about their men taking up with Rebel belles who only inconsistently rebuffed Yankee lovemaking.28

Soldiers starved for culture could read, and many begged their families for printed matter. Although the soldiers would devour salacious literature, or any other kind for that matter, the Christian Commission flooded the army with testaments, tracts, and church papers, and if the agents can be believed, the men welcomed it all. Newsboys also appeared, hawking copies of the New York Herald for ten cents with cries of “another bloody battle.” Other papers sold for less, but soldiers favored the twelve-page Herald because, despite its conservative politics, it was crammed with war news. Soldiers read aloud to their less literate comrades.29 Just as camp gossip powerfully affected morale, so did news reports passed by word of mouth.

Games could, for a time at least, help divert young men from their worries and drain nervous energy. New York and New England troops enjoyed the relatively new sport of baseball. Raggedly played pickup games with scores such as 45-15, 33-1, or 19-17 amused players and spectators alike, especially when inexperienced boys awkwardly tried to master a difficult sport. In an era when a base runner could be put out by plunking him with the ball and regiments were not averse to wagering on the outcome, the rowdiness of the contests became part of the attraction.30

Other soldiers hungered for spiritual solace, and there were even stirrings of a religious revival in the army after Fredericksburg. On gray winter days a real worship service was something to treasure. A Pennsylvania captain described a particularly moving sermon delivered in a fierce wind as “quite a treat and . . . justly appreciated by all the men.” Lively weekday prayer meetings were not as effective as Sunday services in securing bonds between families and soldiers who hankered for worship back home. “Thank God for the Sabbath the day of rest when you lift our souls from the low groveling earth to the heavens above,” a Hoosier exulted. On Sunday afternoons conscientious chaplains visited the hospitals, and the men themselves sometimes passed the time singing hymns.31

These wholesome activities, however, cut against the grain of military life. “Never was there a place where the Gospel was more needed than in the army,” claimed one Massachusetts minister who considered the “social atmosphere” quite “unfavorable” for leading a Christian life. Despite efforts of chaplains, officers, and even President Lincoln, Sabbath-breaking remained the rule rather than the exception. “There is no Sunday in the army” became a camp cliché. The customary day of worship and reflection was taken up with everything from pitching quoits to general inspections.32

Yet men’s contemplation of the horrors of Fredericksburg seemed to have sparked small signs of religious awakening in the camps by late December. Chaplains and visiting evangelists held nightly meetings hoping to win lost souls to Christ. Though the number of converts grew steadily, this was far from a mass revival. The best news a Pennsylvania chaplain could report was that few ever refused a gift testament, but for individual soldiers who had perhaps seldom considered their mortality or relationship with God, the meetings could be real turning points. Many reflected on misspent youth and fretted over their shortcomings before receiving assurance of salvation. Soldiers struggling to lead a Christian life relished letters from home that encouraged their walk with Jesus. Devout men urged relatives to read the Bible and accept Christ as their savior. “Life is short. Death is certain,” Virgil Mattoon of the 24th New York warned his brother, though he held out hope for an “unbroken family circle in Heaven.”33

Religion remained a powerful tie between military and civilian life; but peaceful Sundays at home stood in stark contrast to the soldiers’ current state, and many wondered if they would ever enjoy such simple pleasures again. The war itself remained the greatest test of faith, especially in the aftermath of Fredericksburg. When a Pennsylvania chaplain advised his listeners that everyone must be subject to the higher powers and that government was ordained by God, he broached a touchy subject. Soldiers not only had to connect northern war aims with divine purpose but had to obey their leaders, especially in light of the post-Fredericksburg political uproar. By the same token, a shivering soldier standing picket who could feel the Almighty’s protection would somehow find the inner resources to survive the winter and fight again. Faith that God was watching over individuals at every moment had by no means disappeared despite daily evidence that raised serious doubts.34

Religious devotion, then, became another sign of soldier resilience. Cold weather, poor shelter, monotonous food, and widespread disease surely affected morale, yet the men could always grumble and relish simple diversions. Oaths sometimes drowned out the prayers, and the folks back home might never understand what their loved ones were enduring; but by late December it seemed clear that the Army of the Potomac would not fall apart. At least not yet.

* * *

Neither would the Army of Northern Virginia. Even after their smashing victory, Lee’s men faced the same problems as their Federal counterparts. The Confederates could not officially go into winter quarters so long as Burnside’s intentions remained uncertain. “Very cold. No tents,” a soldier in Jackson’s old brigade reported. Makeshifts dotted the camps. Men burrowed into the ground and covered the hole with a blanket or used brush to block out the wind or fashioned wigwams from sticks, dirt, and straw.35 Captured enemy tents sheltered some regiments, and more government tent flies arrived after the battle. Men with some thin canvas between themselves and the night air seemed fortunate. “I get along with it better than I could expect,” a Georgia captain told his wife after recalling all the comforts at home.36

Veterans saw no reason to build more elaborate quarters when the army might move at any moment to counter another Yankee thrust across the Rappahannock. Better to stay in fly tents than waste time and energy constructing log huts that seemed to one Louisiana artillerist little better than slave quarters.37 For the most part the confident Confederates did complain less than the Federals. Many claimed to be comfortable and even enjoying their crude homes. “Wee live know [sic] like folks and before we lived like hogs,” asserted one North Carolinian who had managed to erect a “splendid house and chimney.” Many more claimed to be “snug” and “warm.”38

Self-assured Confederates could adjust to the discomforts. Great roaring fires with huge logs created a good deal of smoke, but Lt. Ujanirtus Allen of the 21st Georgia seemed to enjoy describing how sooty strands hung from his beard. Green wood and high winds compounded the discomfort. Yet knowing that “the Yankees could not drive us from our position” made Capt. Matthew Talbot Nunnally of the 11th Georgia feel almost cozy. Men could crouch near their tents, smoke a pipe, and perhaps even smile a bit.39

Soaring morale and proud determination, however, could not remedy the army’s severe supply problems. Transportation bottlenecks left coats in Richmond and soldiers freezing in camp; government clothing often proved ill fitting; and complaints received vague, defensive replies from Richmond bureaucrats.40 Worse yet, men were still barefoot or wearing shoes that had long outlived any usefulness. Relief would be elusive. The Confederate government had issued four patents for wooden shoe soles, and some of Long-street’s men were still making moccasins. One of four soldiers in Lee’s only Louisiana brigade remained without shoes; others in the same outfit lacked blankets and even underwear. Soldiers sent home long lists of badly needed items, from boots to socks to overcoats.41 The combined efforts of government, families, and charity never quite covered the needs (or bodies) of ragged Confederates.

Their stomachs were not filled either. Lee’s commissary officers preferred buying food locally but remained dependent on shipments from Richmond. For their part War Department subsistence officers complained of poor support from the cavalry and blamed Lee. Commissary Gen. Lucius Northrop vetoed a scheme to trade government sugar for farmers’ bacon. And so it went. Charges that badly needed supplies rotted in Richmond warehouses elicited familiar excuses about transportation shortages.42

But the sad truth was that Lee’s men were hungry. Rations of flour, bacon, and beef had been steadily reduced. Three daily meals suddenly became two; involuntary fast days were common.43 Fat pork and dry bread seldom satisfied a soldier’s appetite. The bacon was often rancid and the beef tough. “I sometimes think they kill them [the cattle] to keep them from dying,” a Virginia infantryman wryly commented.44

Short rations and cold weather weakened an army already suffering poor health. Letters home read like extended medical reports. Twenty percent of a regiment seriously ill was commonplace, and a daily “sick train” carried the worst sufferers to Richmond hospitals. The cold brought some men to the limits of endurance, so resignations, medical leaves, and severe disabilities thinned the ranks further.45 Aside from the usual maladies, winter brought on fevers, chills, and aches. Fearing he had contracted fatal pneumonia, as had several of his comrades, one Alabamian rubbed his sore chest with turpentine and dosed himself with powdered morphine. Rheumatism also greatly afflicted the thinly clad Confederates.46

Miseries were always relative, of course. High morale mitigated various hardships, yet Lee’s supply problems would continue and could not help but weaken his forces. Cold winds buffeted both armies crouched in tents or shanties. Military uncertainties and the thought of a winter campaign made everyone edgy. The approaching holidays would likely engender more depression and loneliness than cheer and celebration.

* * *

“My heart is filled with gratitude to Almighty God for his unspeakable mercies,” Lee wrote to his wife on Christmas Day. “I have seen His hand in all the events of the war. Oh if our people would recognize it & cease from vain self boasting & adulation.” Perhaps the sacred season would soften hatred and turn Yankees’ hearts toward peace. And if Christmas failed to do this, Lee quickly added the hope that the “confusion that now exists in their [the Federals’] counsels will . . . result in good.” The joys of former Christmases now sadly contrasted to “desecrated and pillaged” Virginia, he told his daughter.47

From his picket post Virginian Henry Krebs considered December 25, 1862, the most “unpleasant Christmas” in his life. Many forlorn soldiers lamented that it was just another dreary day in camp. “No egg nog, no turkey, no mince pie, nothing to eat or drink but our rations,” one soldier lamented. It was a dull, cheerless time, and there were not even any young ladies around. Warm memories of home only added to the ennui. Spiritually minded men looked in vain for signs the army knew the meaning of the holiday. Even back home, secular traditions had already crowded out much of the religious significance; cards, shopping, and presents defined the holiday, especially in cities but elsewhere as well. And these were the things most often missed. A “festival that was formally devoted entirely to pleasure” nearly passed unnoticed in the camps, a Georgia lieutenant reflected.48

Many accounts of the day called it “ordinary.” Even on Christmas most soldiers subsisted on the usual camp fare. A staff officer who had become adept at cooking dishes such as barbecued rabbit jauntily told his wife, “If the darkies all leave us, I shall be able to render you some assistance.” More often, however, soldiers could not hide their sadness. Jesus himself, one Virginian remarked, would have been hard pressed to “furnish a holiday dinner out of a pound of fat pork, six crackers, and a quarter of a pound of dried apples.” Filling his stomach became an imaginary exercise for a Mississippi private who listened intensely as another soldier lovingly described a $7.00 meal he had once eaten at a French Quarter restaurant in New Orleans.49

A fortunate few actually enjoyed real food. One pleasantly amazed Virginia infantryman devoured roast turkey, pig’s head stew, baked shoat, turnips, and dried apple pudding. At a remarkably fine dinner with some high-ranking officers, artillery sergeant Ham Chamberlayne noted how they “were all as merry as if there were no war.” Grateful farmers might offer a nice meal to soldiers guarding their property, but a respectable feed was prohibitively expensive. A $6.00 turkey, a $10.00 bottle of whiskey, or ginger cakes at three for $1.00 quickly deflated a fellow’s enthusiasm, if not his wallet.50

Christmas highlighted the connections between physical needs, emotional pangs, and military morale. Witnesses of the recent carnage sensed what was missing during this normally joyous season: some liquid refreshment to anesthetize the memory. For men used to a cup of cheer at home, a “dull” Christmas readily translated into a “sober” Christmas when a gallon of whiskey cost $40 or more. Longing for his holiday brandy, one Virginian complained to his wife, “I have not smelled a drop this Christmas.”51

Other soldiers got lucky. Some regiments managed a regular holiday spree with whiskey or eggnog, and camps grew boisterous with tipplers singing and carousing. Much of the drinking apparently took place in Pickett’s Division, though even in Jackson’s corps, Alabama and North Carolina troops created disturbances.52 Older Christmas traditions survived even in an evangelical culture, and secularization of the holiday had proceeded even in the rural South. Most surprising, though, is the almost total silence about the day’s spiritual significance for troops with at least a historical reputation for piety.53

Soldiers seldom mentioned Christmas religious services. Reading, foraging, setting off fireworks, yelling, and firing guns in camp helped pass the hours. In the 1st Georgia a private clad in a brown denim suit adorned with yellow paper stars conducted a mock battalion drill and a spirited ribbing of the regiment’s colonel. Role reversal and carnival revelry had ancient roots and nicely matched many enlisted men’s fun-loving and irreverent natures. A minstrel show in Hood’s Division, described by one Texan as “supremely ridiculous,” appears to have represented the high point of holiday entertainment in the Army of Northern Virginia.54

Such merrymaking provided some relief from routine but could never suppress thoughts of home. Memories of Christmases past—the children with their stockings, a cozy fire, a plump turkey, or traditional pound cake—churned up emotions. A miserable Mississippian hoped that at least he and his wife might be gazing at the same stars. For another soldier thoughts of hugging his wife and romping with their sons kept intruding on his attempt to write a letter home. Melancholy reflections, images of loved ones gathering for Christmas dinner, and cordial wishes for a good holiday at home only intensified the pangs of separation.55

On one level, Christmas on the home front followed familiar patterns: newspaper advertisements for books or perfume or brandy, the anticipation of wide-eyed children, and the bustle of holiday meals. In Richmond, young boys set off firecrackers. Yet now women also had to think about soldiers in the hospitals, and the demands on their charity ran up against shortages and inflation. If the Christmas spirit seemed far away to the soldiers, it did to many civilians also. One stricken Fredericksburg refugee had “Tommy’s stocking” as her sole remaining “relic of Xmas.” To make matters worse, Confederate soldiers had stolen the family’s six turkeys on Christmas Eve. Everyone noticed how “different” the holiday seemed. A foreboding gloom overshadowed innocent joy. To a staff officer on leave in North Carolina the explanation seemed obvious: “All thoughts are absorbed in the war.”56

Who could forget all the lives that had been lost during the year? A celebration of a long-ago birth painfully reminded people of ever present death but also became a marker for the course of the war. Even as people gamely tried to keep up seasonal traditions, peace seemed far away. Some Confederates, however, mixed holiday themes with an exuberant nationalism. “The Lord, who is the God of Battles, has looked with favor upon his children of the stubborn South,” a North Carolina surgeon believed. “The bonfire this Christmas is the blaze of victory, and the glad tidings brought by the triumphant chorus of angels, proclaiming ‘peace on earth, good will toward man,’ mingle with these which declare the triumph of liberty, independence, and country.” After a period of “universal defeat, disaster, and disgrace” the Yankees had little reason to celebrate, a Richmond editor observed, and then somewhat incongruously warned citizens about the dangers of complacency and overconfidence.57

Civil religion, however, could not allay the painful thoughts that inevitably accompanied a wartime holiday. With so many men away from home and prices so high, many people expected a “dull” Christmas, though one editor assured the children that Santa Claus would still come. War, however, predated Christ’s birth, and humans had never been able to escape its cruelties. Admonitions to keep the faith in God and country—the heart of official Confederate propaganda—could not keep people from lamenting the wickedness of humanity and the elusiveness of peace. At the end of another year of bloody struggle, hatred, malice, and greed seemed ever more pervasive. Patriotism and determination ran deep in the Confederacy, yet recalling Christmas just one year ago, South Carolina private Tally Simpson found little to celebrate: “If all the dead . . . could be heaped in one pile and all the wounded be gathered together in one group, the pale faces of the dead and groans of the wounded would send such a thrill of horror through the hearts of the originators of this war that their very souls would rack with such pain that they would prefer being dead and in torment than to stand before God with such terrible crimes blackening their characters.”58

* * *

Had Confederates visited the northern camps, they would have discovered that the Yankees, too, wondered what had become of the holiday. Fat pork and hardtack at two or even three meals made Christmas hard to swallow. “A gay old Christmas dinner,” a Massachusetts volunteer ruefully wrote his mother, but at least he had not found bugs and worms in his crackers like one disgusted Michigan soldier. Leftover vegetable soup or a tough piece of beef made for sparse dining, even for men who had grown up poor. “I use to think times was hard at home but this is out of my head,” a disconsolate Pennsylvanian told his sister. To make matters worse, enlisted men heard about generals and their staffs enjoying turkey, mutton, and other good things while they settled for the usual camp fare.59

Yet for all the complaining, the average Federal dined more sumptuously than his Confederate counterpart. Roast beef was a particular favorite, especially if accompanied by potatoes, onions, and biscuits, but pancakes for breakfast or an expensive turkey were likewise relished.60 Some men delighted in simple fare such as beans, rice, and apples, but the sheer diversity of menus suggested that the Union government could supply a large army even under difficult winter conditions. Ingenuity and appetite made up for shortfalls. When one soldier chef concocted dumplings from crushed hard-tack, pork grease, and dried apples, his comrades greedily devoured them.61

Whenever the train whistles blew, the men of the 116th Pennsylvania would yell, “boxes, boxes, boxes.” It seemed just like home to a Maine volunteer. The boys would go to sleep on Christmas Eve “with feelings akin to those of children expecting Santa Claus.” On Christmas Day, however, a long-expected box had still not appeared, and his “mental thermometer not only plummeted to below zero, it got right down off the nail and lay on the floor.” Soldiers blamed such delays on the Adams Express or the War Department, and as always, many boxes arrived with the contents jumbled and provisions spoiled. Inevitably, too, boxes reached the camps addressed to men who had been killed or seriously wounded, and the contents would be quickly auctioned off.62 Thus even feasting offered no respite from reminders of death.

Some regiments did draw a whiskey ration on Christmas Day. One Pennsylvania lieutenant even noted how men used to voting as “repeaters” back home got into line more than once. Soldiers understandably tried to assure their families that they had not spent the holiday in a drunken debauch. An Indiana major told his wife he did not drink nearly as much as he had at home, but he might have been lying or been deterred by the poor quality of the booze. Government-issue whiskey was often nasty, though that hardly stopped the hardcore drinkers.63

Statements about the entire army roaring drunk made for colorful exaggeration, but the whiskey punch flowed freely, especially among company officers. Provost guards remained on alert to quell disturbances. Men firing pistols or slashing the air with sabers presented some danger, though many tipplers passed out harmlessly before being carried back to their tents. Here and there a fistfight would break out or thirsty men would raid a sutler’s stock, but that was the extent of the violence. One surgeon who deplored soldiers “making beasts of themselves” and acting like a “heard of swine,” nevertheless understood that they probably considered “oblivion” better than “miserable recollection.”64

Although the horrors of Fredericksburg still haunted men’s minds, on Christmas Day domestic concerns dominated their thoughts. Like the Confederates, Federals simply wished they were home. Imagining one were again with one’s wife or children could relieve the oppressive dullness of camp. Men could envision the eager young folks hanging their stockings, the tree decorated, and families praying for their safety. As at Thanksgiving, the soldiers could see and almost taste the food or feel the warm family hearth and the familiar church pew.65

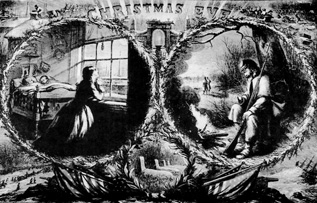

In lonely camps men prayed for their families and tried to rekindle the season’s message of love and peace—no easy task in 1862. Thankfulness offered hope, but a hope tinged with sadness, especially when the usual exchange of gifts could not take place. One Michigan lieutenant noted Christmas Day briefly but then decided he had better tell his wife how much he loved her and appreciated her as a Christian mother. Perhaps he was expressing his true feelings, just in case. No wonder a New Hampshire private cherished a Harper’s Weekly drawing titled Christmas Eve that showed a wife earnestly praying at home while in another panel her soldier husband sat near a small sentry fire. Walter Gordon McCabe’s poem “Christmas Night of ’62” recaptured not only the soldiers’ often maudlin sentimentality but their dreams of family.

There’s not a comrade here to-night

But knows that loved ones far away

On bended knees this night will pray;

“God bring our darling from the fight.”66

Actually the home folks preparing for the holiday were as likely to be buying as praying. Advertising in northern newspapers was both more extensive and more elaborate than in the rapidly shrinking Confederate sheets. Column after column touted the latest fashions, makeup, books, and toys. New laborsaving sewing machines promised help for the harried housewife. The sale of superfluous objects such as napkin rings, card baskets, and berry dishes in Baltimore just as Burnside’s army was poised to cross the Rappahannock seemed anomalous if not obscene. But even the worst battlefield news could not drown out the din of holiday commerce.67

December 1862 hardly seemed the appropriate time for a spending spree, however. To a Quaker woman living in Delaware, many people tried to balance “festivity” with charity. Folks seemed less “wrapped up in selfish enjoyment” and more willing to hold Christmas dinners for soldiers’ children or visit the hospitals. In Washington, Elizabeth Walton Smith, wife of the soon-to-be-departing Secretary of the Interior Caleb Smith, organized special meals for the sick and wounded in some twenty hospitals. Mary Lincoln, Stephen A. Douglas’s widow, and several senators’ wives waited tables.68

Christmas Eve (Harper’s Weekly, January 3, 1863)

The joy and sadness of Christmas in 1862 made civilians and soldiers alike think more about their lives and times. Amidst wartime suffering, children would enjoy the holiday, and newspaper reports of gifts for the soldiers and visits to hospitals would impart to readers the usual warm, secure, and slightly smug feeling that Americans were decent people after all despite the war. To George Templeton Strong, Christmas still meant beautiful music and peace on earth even in a time of wrenching upheaval. For a Pennsylvania infantryman who had witnessed some of the worst carnage on December 13, the essential fact remained that he was still alive despite a surely perilous future.69

The feelings of the season could be summed up in the word “sacrifice.” A member of the Irish Brigade, still reeling from the horrific bloodshed, kept thinking of all the widows and orphans. In New York, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts it would be a “sad, sad Christmas” around “many an Irish hearthstone.” Soldiers still lamented lives needlessly squandered for the sake of scheming politicians and perhaps for a cause now hopeless.70

Over all loomed the prospects for a winter campaign. Chilly winds, sparse rations, and camp routine had probably reduced optimistic Confederates’ fighting edge despite apparently soaring morale. The better-supplied Federals could not yet shake the postbattle blues. Most of these men would still fight, and a remarkable number would eventually reenlist. The noble cause of liberty, a struggle for freedom and national unity, made Christmas worth celebrating, especially for Republicans with a strongly antislavery bent. Though many cynical soldiers would have ridiculed such sentiments after the slaughter at Fredericksburg, Pvt. Isaac Taylor of the 1st Minnesota, for one, remained steadfast: “May the peerless ray of Freedom’s sun dispel the thickening gloom & bring us peace & unity.”71 Yet defining that word “freedom” remained a tricky and treacherous and anything but unifying exercise.