25 Mud

An army can pass wherever a man can set foot.

—Napoleon

When would the government finally figure out what to do with the Army of the Potomac? That was the question of the hour, according to the New York Times, and it was repeated by editors, politicians, civilians, and soldiers. “The army can’t lay here all winter,” Col. Robert McAllister of the 11th New Jersey decided. Little did the carping complainers living comfortably at home “know of the suffering in our army—suffering by cold, wet, and disease that are carrying down thousands of our brave men to an untimely grave.”1 Veterans knew firsthand the difficulties of winter campaigning, but practicalities never stopped armchair strategists.

Noted military thinker Horace Greeley claimed that this war somehow differed from all previous wars: “Its boiling blood refuses to be tempered by the fiercest blasts of Winter. Its immense armaments, its tremendous stretches of exposed and raid-inviting frontier, alike forbid the thought of months of hibernation.” Burnside nursed no illusions about how long the administration or the northern people would be patient. In a four-column, front-page dispatch William Swinton of the New York Times described the army as a “melancholy muddle.” He quoted Halleck as saying, “The Army of the Potomac has ceased to exist.” Swinton thought Burnside a good-natured, conscientious man who lacked both the confidence and the intelligence necessary to command a large army. A run of good weather had already passed, and now it was too late to launch another offensive with demoralized troops. Swinton was no lone voice. Republican and Democratic editors insistently asked why the army remained idle.2

It was not totally idle, however. Cavalry and engineers scouted crossing points, while infantry detachments corduroyed roads. Dubious intelligence, including a report that part of Longstreet’s corps had been ordered to Tennessee, caused further fits and starts.3 General Patrick considered Burnside (perhaps again suffering from mental strain and overwork) “obtuse” and “very forgetful” about details. Yet his plan was in place: to cross the army upstream from Fredericksburg at Banks and United States fords with a diversionary maneuver below the town involving newly arrived infantry, navy tugs, mortars mounted on boats, and transport vessels. Other generals remained unconvinced. Besides having to contend with his army’s internal bickering and sagging morale, Burnside was violating an important Clause-witzian principle: “When a battle is lost, the strength of the army is broken—its moral even more than its physical strength. A second battle without the help of new and favorable factors would mean outright defeat, perhaps even absolute destruction.”4

Most soldiers would not have quibbled with the great Prussian theorist’s statement. Despite evidence that the Federals had begun to recover from the effects of Fredericksburg, signs of demoralization had also returned. On Wednesday, January 14, after a cold rain, three discouraged soldiers noted the presence of something else that could sabotage any winter campaign: mud. Mules could hardly slog through the soft ooze, and the thought of pitching new camps much less moving an army appeared ludicrous. The prospect of more marching, sleeping without tents, and all without pay appalled one Maine volunteer. “Do you wonder... that the Soldier is disheartened, discouraged,” he asked his sister. “If the government wants Soldiers that is ready to do Let them treat them as men not as Brutes.”5

Fear, despondency, uncertainty, and a persistent loyalty whipsawed emotions. An Indiana cavalryman stripped the problem down to its most fundamental elements: the “great struggle of the war” had begun and “many thousands may perish.” Yet to him the Army of the Potomac seemed tough enough to go up against Lee, and gritty determination survived even in demoralized regiments.6 At the same time apprehension, doggedness, and hints of bravado made for an odd psychological mix. “I am getting to be a believer in pre-destination,” a Massachusetts officer said, and indeed many soldiers sounded a note of Lincolnesque fatalism. Such an attitude expressed a sad indifference to the war, a demoralization that drained the patriotism and even the determination to fight for home and family right out of the troops.7 What such diverse attitudes and emotions added up to, only the next campaign would tell.

Few portents held any promise for success. “Our army here is almost ruined and melting away rapidly,” Senator Fessenden noted sadly. “Traitors are about as thick at the North as at the South, and how soon the government will find itself without support it is hard to say.” Alarmists among Republican House members warned that McClellan Democrats dominated the officer corps, and conservative newspapers spread treason among the enlisted men. “Burnside is a slow coach and will do nothing effective,” Senator Chandler observed.8 The first reports of the Army of the Potomac leaving the camps aroused surprisingly little enthusiasm in the northern press, despite previous, unrelenting calls for action. Normally “On to Richmond” editors evidently anticipated another reverse, fully expecting Lee to counter any Federal thrust.9

Confederate cavalry kept a close watch on the Federals, and each day the infantry strengthened its positions. On January 16 Lee arrived in Richmond to confer with Jefferson Davis but hurried back to camp the next day amidst reports of Federals stirring across the river. He had no idea of Burnside’s intentions and still would retire to the North Anna line should the Federals cross the Rappahannock again—a course of action that would displease Davis.10 Rumors of enemy movements failed to shake the aplomb of Lee’s soldiers. They did not need to know how Marse Robert planned to thwart the Yankees this time. Burnside might force them into battle again, but they harbored few doubts about the outcome.

* * *

Friday, January 16. Ready to march at last. “No one sorry to move,” a New Hampshire volunteer claimed. “Almost anything is preferable to this vile camp.” Burnside’s headquarters ordered batteries to cover crossing points and teamsters to drag pontoons toward the river. “The morale of the army is not now right for such a move,” a Michigan captain feared. Perhaps the orders would be countermanded.11

Saturday, January 17. In the early morning hours as word spread that the army would cross the river and flank the Rebels, quartermasters and ordnance officers scurried about. “I have yet to see the first man who approves of the movement,” an officer in Doubleday’s division grumbled. Not surprisingly, his comrades appeared “hopeless,” “despondent,” and “dispirited,” to this McClellan loyalist. Yet reports of demoralization and threats of mutiny even circulated among Humphreys’s stalwart Pennsylvanians and the Regulars in Sykes’s division. Franklin suggested a delay until Monday so more roads could be corduroyed, but he may have simply been buying time, hoping for bad weather to foil Burnside’s plans. By 10:00 A.M. the marching orders had been countermanded again. Cpl. George Mellish of the 6th Vermont spoke for many enlisted men: “All is uncertainty in the army.”12

Sunday, January 18. “How long the present state of affairs and suspense will continue is known only to wise heads at Washington,” a New Yorker in the Fifth Corps bitingly commented. Cooked rations placed in haversacks several days earlier had begun to spoil; men receiving boxes from home wolfed down food just in case they really did break camp this time. One thing was certain: the good weather would not last forever. Maybe God would bless this effort, but then again another slaughter might await. “I think the soldiers will go forward, very reluctantly,” a New York artillery officer predicted. The boys understandably said more than a few prayers on this somber Sabbath. Still uncertain about timing, Burnside waited for a spy to return from the other side of the river and decided not to send troops across at United States Ford, where the Rebels appeared strong. Once again the anticipated movement never got started. A Massachusetts lieutenant colonel dubbed the army the “Snail of the Potomac.”13

Monday, January 19. A conversation between Burnside, Franklin, and Smith grew heated. The latter two predicted the campaign would fail because the Rebels were too powerful and their own troops were too demoralized. Barely controlling his anger, Burnside dismissed their objections. After visiting Franklin’s headquarters, First Corps artillery chief Wainwright was appalled: “Both his staff and Smith’s are talking outrageously, only repeating though . . . the words of their generals. Burnside may be unfit to command this army; his present plan may be absurd, and failure certain; but his lieutenants have no right to say so to their subordinates.... Franklin has talked so much and so loudly . . . that he has completely demoralized his whole command, and so rendered failure doubly sure.... Smith and they say Hooker are almost as bad.”14

Soldiers still assumed they would be leaving the camps soon, even though by early afternoon the movement was again postponed. For sure, a great number of troops would be “missing” once the army crossed the Rappahannock. A winter campaign with men already unhealthy held no charms for wary veterans. Some soldiers were reportedly “groaning Abe Lincoln & cheering Jeff Davis.”15

Tuesday, January 20. The suspense ended. “The Army of the Potomac [is] about to meet the enemy once more,” began General Orders No. 7. “The auspicious moment seems to have arrived to strike a great and mortal blow to the rebellion.” Besides urging “gallant soldiers” to earn ever more lasting “fame,” Burnside also enjoined “firm and united action of officers and men,” a stark illustration of the problem. He was sending troops into a campaign against the advice of his senior generals, and their doubts had infected junior officers and enlisted men.16

Although some soldiers in green regiments and a few Ninth Corps stalwarts actually cheered the orders as they were read, most outfits responded tepidly or worse. In Howard’s division members of the 15th Massachusetts and the 42nd New York “hooted” at both the orders and Burnside.17 Too many men had given up on Burnside. “One more defeat would fix him,” a New Yorker predicted. A veteran artilleryman claimed that “everyone has been praying for rain or a snow to stop it.” Were the troops near mutiny, demoralized, or merely unenthusiastic? Their words expressed both momentary pique and deep disillusionment. Discerning the army’s mood at this point required making fine distinctions, especially when a few soldiers were actually optimistic. A brave Ninth Corps volunteer could feel the country’s gloom lifting and could almost hear people cheering the coming victory. Such eagerness was rare. A Michigan surgeon better expressed the skeptical fortitude that held the poor, battered Army of the Potomac together: “I hope the army will go to Richmond this time or to hell, and I don’t care which.”18

At 1:00 A.M. on January 20 Maj. Gen. John G. Parke, Burnside’s chief of staff, had issued orders for Hooker’s Center Grand Division to cross “just above Banks’ Ford,” with one division to assist General Woodbury in laying pontoons. Late in the morning Burnside filled in the details. Once over the river, Hooker would reestablish communication with Franklin (who would have crossed just below Banks Ford), “secure a position” on the Orange Plank Road west of Salem Church, and prepare to attack should the Confederates abandon their position at Fredericksburg and head south on the Telegraph Road. Hooker ordered his troops to be ready to march by 11:00 A.M.19

With temperatures inching above freezing and the roads in good shape, regiments began leaving their camps; a band struck up “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” As the ground thawed during the afternoon, one New Yorker noticed “twelve foaming, panting, weary horses tugging at each slow-moving [artillery] piece.” Assigned to assist with pontoons, Birney’s division advanced to within less than two miles of Banks Ford. As usual, moving troops along country roads proved confusing and slow. Some of Hooker’s men halted to let regiments from Franklin’s grand division pass and consequently marched no more than a mile or two.20

In Sickles’s division, soldiers cursed anyone who tried to prod them along and yelled for officers to climb off their horses and carry a knapsack like a real soldier. “I’m demoralized,” one man shouted. From the beginning the march prompted sardonic humor, the veterans’ perennial defense against official imbecility. Some men joked about “Burned Side.” Others posed a riddle: Why was the Army of the Potomac like a frog? Answer: “It is always found in a mud puddle.” One wit suggested the army had a “damned little head for so long a tail.”21

Franklin’s orders called for sending a division to assist with the pontoons, crossing the river below Banks Ford, advancing toward the Orange Plank Road, and finally turning east to confront the Confederates a little more than a mile away on Marye’s Heights. Around noon from camps near White Oak Church, elements of the First and Sixth Corps headed west. Some regiments marched a dozen miles; others, only three or four on the jammed roads.22

“On the march today the disaffection produced by Franklin’s and others’ talk was very evident,” Wainwright noted. “The whole army seems to know what they have said, and their speeches condemning the move were in the mouths of everyone”—an exaggeration no doubt, but suggestive of trouble ahead. Men naturally indulged their penchant for grumbling, and in some outfits straggling began immediately.23

By early evening, as tents were being pitched, rain had started, lightly at first, but by midnight the heavens had opened up. Water flowed into some tents; a gusty east wind blew others away. Lt. Samuel S. Partridge of the 13th New York, already feverish, spread his rubber blanket on the ground, wrapped himself up in soggy covers, and almost got comfortable after some friends tucked him in with a tarpaulin. Men futilely tried to dry out around smoky fires that mostly made their eyes water. In one of Birney’s brigades a “generous” whiskey ration elicited much shouting and some fighting. At a loss for words, a Pennsylvanian wrote in his diary, “O! what a night.”24

The cold, wind-driven rain seeped through uniforms and slashed the faces of soldiers without tents. Men stoically chewed hardtack and pork. During the night the cries from some sufferers kept almost everyone awake; boys threw blankets over their heads, sat on logs, and waited miserably for the gray dawn. Some men spent the night exchanging mordant jokes around sodden fires. One of the Pennsylvania Reserves who managed to fall asleep awoke the next morning in “about half a foot of water and... stiff as an old horse.” With the endless night over, men staggered to their feet. Every stitch of clothing was wet, and waterlogged knapsacks weighed them down.25

Wednesday, January 21. At 4:00 A.M. reveille sounded for Hooker’s men. The steady rain had produced a “complete sea of mud.” Wagons sank up to their axles. But by lashing the teams and some “prodigious blasphemy,” the “spiritless” troops crawled perhaps three miles. One of Sykes’s Regulars summed up the situation: “Burnside cannot fight with troops out of heart.” By early afternoon nearly everyone had fallen out of line exhausted.26 Entire companies tugged at ropes to pull supply and ammunition wagons from the mire. Countless pairs of boots were filled with water and mud—the ultimate soldier misery. The rain had accomplished what many thought impossible: it had even ruined hardtack. With rations soggy and spoiled, mudsplatterd men grimly recalled how they had started at daybreak without so much as a dipper of morning coffee and now faced the prospect of no supper.27 Such discomforts weighed far more heavily on their minds than grand strategy.

Franklin’s troops slogged four or five miles, though few of the pontoons or artillery ever got close to where the bridges were to be laid. By noon many regiments had given up the struggle. As rear guard for the ammunition train, members of the 16th Maine had to unload wagons and heft boxes uphill, gaining no more than a half-mile. It was a “wade on to glory,” a Wisconsin volunteer wryly commented. It had not taken long for every man and beast to become covered with what they ruefully called the “sacred soil” of Virginia. Soldiers and animals alike became nearly unidentifiable—a fact lovingly recounted and embellished for years afterward.28

Dropping out, panting, and sweating after several hours of great exertion, men sat on the same waterlogged blankets that had “seemed like so much lead” during the march. The air hung so heavy with moisture that smoke from fires hovered near the ground, adding to the wretchedness of yet another cheerless bivouac. After watching men toss away their gear while wrestling with mules and artillery, a Sixth Corps sergeant pointedly remarked that McClellan had been right about the futility of winter campaigning.29

“Mud is King!” a New York surgeon had written prophetically little more than a week earlier. “More of a sovereign, and a worse despot than cotton and ten thousand times more to be dreaded by such an army as ours when we want to move than all the inventions and machinations of our enemies.” The reddish, weathered-clay soil held water and stuck to anything. The soldiers strained for words: “river of deep mire,” “a vast mortar bed,” “the mud is ass deep.” It seemed almost alive as it sucked and grabbed men and equipment. “Your feet sink into it frequently ankle deep, and you lift them out with a sough,” a Pennsylvania lieutenant recalled. An imaginative volunteer composed some appropriate doggerel:

Now I lay me down to sleep

In mud that’s many fathoms deep;

If I’m not here when you awake

Just hunt me up with an oyster rake.30

As was obvious to all, rain had made the Virginia roads virtually impassable. By the morning of January 21 only three pontoon trains had neared Banks Ford, and Woodbury predicted it would be several more hours before they could be hauled the final mile over the sloppy roads. Across the river he noticed signs of Rebel preparations and suggested that the night’s fires had alerted the enemy. Late and confused orders had once again foiled Burnside’s plans, but the engineers and supporting infantry had shown little enthusiasm for the work. Some wagons had reportedly been sabotaged, and there were rumors that “bad whiskey” had slaked the fighting spirit. Worn-out teamsters abandoned their animals, wandered off searching for food, and in a few cases unhitched mules and rode away. Scores of men with long ropes tried to drag pontoon trains up small rises, but by early afternoon they had given up from sheer exhaustion.31

“Profanity gulch” described a ravine where artillery pieces and wagons became hopelessly entangled. Unfortunately swearing could not extricate a battery from the mire. Attempts at prying guns loose with long levers and even double-teaming the horses proved futile. As wheels sank deeper, men waded in up to their ankles. Infantry detachments corduroyed more roads; but pieces of wood caught in wheel spokes, and one officer observed how even these thoroughfares quickly deteriorated into a “miry pine brush.” Smashed-up and capsized pontoons, broken-down caissons, and pieces of guns and wagons marked the track of a failed campaign.32

The march was torture for the animals. Stouthearted army mules, creatures known for their endurance under rough treatment, could not handle the wretched footing. Once mired in mud, the hapless beasts stopped pulling and eventually died. A sketch artist noted how “clouds of vapor... rose from the overworked teams” straining under drivers’ curses and whips. Horses lay along the roadsides dead or nearly so; some dropped in their harnesses; others broke their legs straining against heavy loads. A Pennsylvania lieutenant came across a heavy wagon stalled in a “slough.” Four mules struggled to get out but could not, even after they had been cut loose from their traces. A chain fastened to one mule’s neck and pulled by a wagon freed the animal but also broke its neck. A second mule shared the same fate. The other two mules stopped struggling as they sank deep into the muck, and their suffering was finally ended by merciful bullets.33

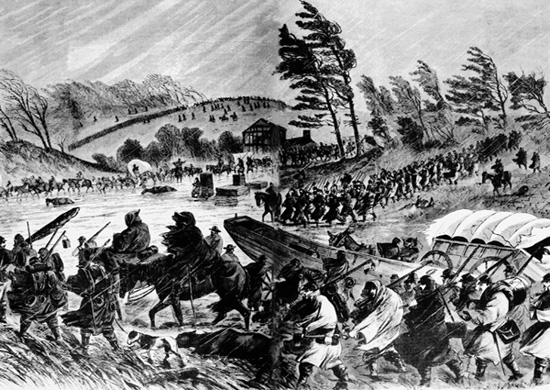

After breakfasting on tea and toast, Burnside and four staff officers rode off toward the river in the rain. Seeing the “careworn” general covered with

Alfred Waud, The Mud March (Harper’s Weekly, February 14, 1863)

mud, one Vermonter decided that perhaps the infantry’s burden was lighter than its beleaguered commander’s. Around 5:00 P.M. Burnside and his party returned to camp. Discouraging dispatches awaited. Burnside himself had seen the sodden spectacle: twenty horses unable to budge a caisson, 100 soldiers struggling with a pontoon train, and animals and men used up. Yet he bristled at the pessimistic reports from Woodbury, Franklin, and Hooker, and complained that some generals had done everything possible to thwart his plans. Over dinner Burnside tried to appear cheerful. At 11:00 P.M., how-ever, he telegraphed Halleck that a “severe storm” had delayed the march and allowed the Rebels to “discover our designs.” He finally bowed to the inevitable: “It is most likely that we will have to change the plan.”34

Thursday, January 22. At breakfast Burnside remarked that Hooker now placed the odds against success at nineteen to one; Franklin and Woodbury had offered similarly gloomy assessments. A New York Times correspondent overheard Fighting Joe dismissing the government as “played out” and talking about the need for a dictator. Facing generals as hopeless as the roads, Burnside finally ordered Hooker and Franklin to bring their troops back to the camps.35

Friday and Saturday, January 23–24. The return trip was pure hell. Infantry lugged fence rails, logs, and brush for corduroying roads. Even so, pulling artillery pieces killed more horses and mules. Guns and wagons sank to their axles, and it required the better part of two days to get the pontoons back to Falmouth. Foul tempers and finger-pointing between the infantry, artillery, and cavalry further slowed the retreat.36

Organization had simply broken down, and each man struggled along on his own. Straggling, already a serious problem during the early stages of the march, obliterated any sense of discipline. Plagued with diarrhea, Cpl. Joseph Bloomfield Osborn of the 26th New Jersey had naturally fallen behind. In the continuing rain the woods where he had taken shelter filled with cursing men, some vowing they would never “fight for the nigger.” A few broke their muskets across trees, claiming that more than half of Franklin and Hooker’s troops had done the same. A forlorn, mud-spattered group of twenty soldiers reaching their old bivouac identified themselves in response to challenge as “Stragglers of the Seventeenth Maine, Sir!”37

Sumner’s troops shook their heads in amazement as they watched a stream of dirty and exhausted soldiers troop by their tents. Members of the faithful old Ninth Corps could hear Hooker’s and Franklin’s men offering “three groans” for Burnside or joining a lugubrious chorus of what was turning into a campfire favorite, “Burnside’s Army Lies Floundering in the Mud.” A volunteer in Getty’s division described one group of stragglers as “muddy, wet, ugly, sour, and insubordinate.”38

* * *

More unpleasant surprises awaited the returning troops. Soldiers in Double-day’s division discovered that some of Sigel’s troops had taken over their old campsites. An Ohio regiment had torn down shanties for firewood, and other soldiers occupied huts that had been carefully constructed by First Corps outfits right after Christmas. After an exchange of curses, the interlopers usually departed.39

For several days after the Mud March a trickle of desertions turned into a steady stream. Many regiments reported that a man or two had run off during the preceding week. Pickets slipped away from their posts, and groups of deserters hid in the woods from cavalry patrols. The usual sentences of fines or hard labor would not likely stem this tide. Morale had apparently hit bottom.40

During and after the Mud March, officers and men in every corps, including troops in the Right Grand Division that had not even left their camps, received whiskey rations. “If no worse use is ever made of liquor than this,” a New York surgeon remarked, “surely the cause of temperance has no reason to complain.”41 Such an opinion depended on one’s perspective, of course. “Camp was like a pandemonium,” said a New Jersey volunteer. Drunken men staggered around cursing Burnside, and one colonel speculated that the Rebels could have easily crossed the river and captured many prisoners. Exhausted and demoralized troops appeared determined to drown their troubles, and no beverage could serve better, a Pennsylvanian claimed, than commissary whiskey. As the precious liquor was being poured into canteens, a fight broke out in the 118th Pennsylvania. Men from the 22nd Massachusetts and the 2nd Maine joined the fray; when a major wielding two cocked six-shooters tried to restore order, they knocked him into the mud.42

The men had reason to drink. Not only had the latest campaign ground ignominiously to a halt, but without even bringing on a battle, it was killing people. Weakened soldiers had fallen ill and died along the way. Ambulances carried the sick back toward a newly constructed hospital at Aquia Creek, where some patients still lay on the ground in tents without fires. Meanwhile, burial details kept busy turning up the soggy earth.43

It seemed as if God again held the army’s fate in his hands. On one hand, a “providential” rain had prevented another murderous battle. “Heaven muttered at the deed and sent an angel to stop it,” a Connecticut sergeant declared. On the other hand, a thoughtful private who could hear church bells ringing in Fredericksburg reflected on how the Rebels were “praying earnestly for our discomfiture and utter annihilation.” Still, “we have at least an equal number of good Christians at home,” he told himself, “with just as good voices and just as determined spirits.”44

Other soldiers, including Meade and Humphreys, believed the army might have won a great victory and played down reports of demoralization.45 But despite a certain core of unyielding resolve, Burnside would not be spared scalding postmortems. Even men who felt sorry for their commander admitted that his best efforts had failed. Many others called for his head. Franklin’s soggy troops openly vowed to “sit up nights cursing Burnside.” An earthy Vermonter sarcastically remarked, “Burnside has shit his breeches this time.” Doubts about the general’s abilities had now hardened into convictions about his incompetence as cries for Little Mac’s return reached a crescendo.46

Words such as “disheartened” or “desponding” and most of all “demoralized” appeared in letters describing the army’s condition. The Mud March had been more discouraging than Fredericksburg, claimed one of Humphreys’s Pennsylvanians.47 Men talked of throwing down their arms. Presumably the Rebels would quickly follow suit, both armies would melt away, and peace would dawn. A Michigan private felt like a man in a sinking ship surrounded by sharks and “going swiftly . . . to the Devil.” The very idea of a victory by this God-forsaken army seemed ludicrous to soldiers who again noted how many of their comrades were dying for no purpose.48

The army seemed “played out,” in soldier parlance. “Its patriotism has oozed out through the pores opened up by the imbecility of its leaders, and the fatigues and disappointments of a fruitless winter campaign,” a New Jersey corporal wrote sadly. Only “honor and self-respect and an adherence to their oath” prevented mass desertions. An equally disgruntled Massachusetts officer predicted the army would become a “source of great trouble to the government if things go on in this way much longer.” Enlisted men swore they would never fight again; there appeared to be far “too many officers of the Governor Seymour stamp.”49

Men who still cherished the Union cause or at least remained determined to complete their enlistment blamed “croakers”—in the ranks and at home—who spread their poison among the gullible. “Fault-finders and gloomy prophets,” especially in the northern press, a Pennsylvania volunteer complained, were “doing more for the enemy than they can do for themselves.” Spying a newspaper correspondent from some “On to Richmond” sheet, Pennsylvanians in the Sixth Corps peppered him with irreverent questions: “Why don’t the army move?” “When did you learn to be a general?” “Does your mother know you’re out?” “What do you get apiece for lies?”50

The Confederates delighted in their enemies’ plight. Reports rapidly spread from the camps to the newspapers and finally to the southern home front that the Army of the Potomac had become completely demoralized.51 Southerners’ response to Federal maneuvers had largely been contemptuous. Confederate soldiers had set up “hand boards” with “large letters” that read, “BURNSIDE STUCK IN THE MUD.” Scornful pickets shouted to the Yanks with mockingly polite invitations to come over or offers to help with the pontoons. Rebel bands played “Dixie” and, for good measure, a few Union airs.52

As despondent bluecoats magnified the depressing effects of the Mud March, exuberant Confederates overstated their enemies’ discomfiture. “If the Yankees had crossed the river, we would have whipped them easily” became their steady refrain. Next time, perhaps, General Lee would bag the entire lot. A Charleston correspondent reported the Army of Northern Virginia in high spirits and good health and full of boundless confidence. Less straggling, better clothing, comfortable quarters, and spirited drilling all bolstered an indomitable fighting spirit. An optimistic Georgian who expected the war to be over by July 4 began thinking about the hair-raising tales he would tell his wife after he returned home.53 Lee refrained from such wishful thinking, but the mutual trust between a seemingly invincible commander and his brave troops sent Confederate hopes soaring to dangerous heights.

At the same time, northern spirits sank lower. Newspaper descriptions of artillery, wagons, men, and animals floundering in the mud soon appeared. Republican editors tried to play down signs of demoralization, but people did not find their assessments credible. “Northern dirt-eaters grow more insolent and shameless everyday,” George Templeton Strong wrote wearily. “False, cowardly, despicable sympathizers with Rebellion” had gained far too much influence over a weak-kneed public. Reports of insubordination among Burnside’s generals prompted the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War to launch another investigation. New York Times editor Henry J. Raymond, who had spent several days at Burnside’s headquarters during the Mud March, reported widespread discontent and suggested that either the troublemakers be removed or that a new commander be appointed.54

At last Burnside prepared to move against his enemies by drafting a set of orders that would have shaken the Army of the Potomac to its foundations. Numerous heads were going to roll. He proposed dismissing Hooker from the army for “unjust and unnecessary criticisms of the actions of his superior officers.” Generals Newton and Cochrane and Brig. Gen. William T. H. Brooks, a division commander in the Sixth Corps, would also be sacked. Generals Franklin, Smith, Sturgis, and Ferrero were “relieved from duty.”55 These blows to both Hooker and the McClellan faction would likely produce a political firestorm. But the commander’s mind was made up, and when asked what he would do should Hooker attempt to incite a mutiny, Burnside replied that he “would swing him before sundown.” In any case, he would travel to Washington seeking Lincoln’s approval for the dismissals.56

The journey to the capital typified the man’s bad luck. On January 23 at 8:30 P.M. Burnside, Raymond, Larned, and a servant started for Falmouth in an ambulance. In the foggy darkness the driver, who was both nearsighted and deaf, drove them over an embankment, and they became stuck near a pile of dead mules. The hapless party stumbled through the mud, taking three hours to cover the three miles to the station. But the engine had already left, so with Burnside carrying a lantern, the forlorn group trudged toward Stoneman’s Switch and, after walking two miles, managed to flag down a locomotive. By the time they arrived at Aquia Landing, boarded a steamer, and reached Washington, it was after 6:00 in the morning.

Leaving his companions at Willard’s Hotel, Burnside went off to see Lincoln. He handed the president General Orders No. 8 along with a note resigning his commission. Reiterating that he had never sought the command in the first place, Burnside somewhat petulantly remarked that he would gladly return to civilian life. “I think you are right,” the president replied, “but I must consult with some of my advisers about this.” Lincoln had received what amounted to an ultimatum. Burnside’s sudden stubbornness left no room for diplomatic niceties, even for a president. In a response that likely surprised and irritated Lincoln, Burnside sharply commented, “If you consult with anybody, you will not do it [approve the order], in my opinion.” Lincoln dismissed the objection: “I cannot help that; I must consult with them.” The president could do as he pleased, Burnside observed icily.57

On Sunday morning, January 25, Lincoln informed Stanton and Halleck that he planned to replace Burnside with Hooker. He had not conferred with the cabinet, and he did not leave the matter open for discussion. Like much of the country, he had lost faith in Burnside. For all Fighting Joe’s faults—his shameless plotting was no secret to Lincoln—there seemed little choice but to act now. When Burnside arrived around 10:00 A.M., Lincoln informed him of the decision. The general took the news with apparent equanimity, glad to be free of a terrible burden. He loyally hoped that Hooker would win a great victory. Lincoln would not hear of Burnside giving up his commission and instead granted him a much needed thirty-day furlough.58

Stanton issued orders relieving Burnside of command “at his own request.” Sumner, largely because of his age, and McClellan’s friend Franklin would also depart. At last Joe Hooker received the appointment for which he had schemed so long. After returning to Falmouth, Burnside visited Sumner’s headquarters, where their conversation, undoubtedly reliving old triumphs and disappointments, ran well into the night.59

The next morning Col. Zenas Bliss of the 7th Rhode Island stopped by Burnside’s headquarters and found the general in shirtsleeves, champagne bottle in hand. Over a convivial drink Burnside bitterly remarked, “They will find out before many days that it is not every man who can command an army of one hundred and fifty thousand men.” At 10:30 A.M. several officers, including Hooker, arrived to bid their former commander farewell. Burnside addressed them with what General Patrick considered “some feeling”; he was overheard to say, “There are no pleasant reminiscences for me connected with the Army of the Potomac.” For a time the atmosphere grew tense. Yet he issued a gracious farewell order praising his successor as a “brave and skilled general” and wished the army “continual success until the rebellion is crushed.” At noon Burnside, Sumner, and Larned departed for Washington.60

As word of the change spread, soldiers high and low had the final say. The sympathetic Meade concluded that Burnside had been unequal “to the command of so large an army” and “deficient in that large mental capacity which is essential in a commander.” But Burnside “appeared much like Washington to the troops that knew him best,” said a loyal Ninth Corps corporal, one of the few such ardent defenders left. Soldiers still admired Burnside’s manly assumption of responsibility, and several men noted how uncontrollable factors—notably the weather—had ruined his plans. Perhaps fate or even God’s will had been against him. No one could doubt Burnside’s honesty or patriotism, but even admirers conceded his lack of self-confidence and the army’s subsequent loss of faith in him.61

Some irreverent fellow had reportedly asked Burnside shortly before his removal, “When are you going to butcher again?” The story spoke volumes about the opinions of ordinary soldiers. Disheartened troops influenced by disaffected officers had recently howled and hooted at Burnside. A corporal in the First Corps thought news of the change in generals “too good to be true.”62

The army’s new commander condescendingly noted “the gloom and despondency which has settled over the mind of the army through the reverses and imbecility of my predecessor.” But like Burnside, Hooker would have to deal with troops whose heart in many ways belonged to McClellan. Many veterans still believed that only the Young Napoleon could command the Army of the Potomac.63

* * *

Demoralization continued to dog the army. “Everybody appears indifferent to the appointment of Hooker,” a Ninth Corps New Yorker wrote. “Heroes of many defeats we are not inclined to gratuitous confidence in anyone.” This was not entirely accurate, because some soldiers welcomed the change and expressed great confidence in Hooker. Other men, however, feared they had become mere playthings to be marched about, thrown into battle, and slaughtered—all on the whim of some incompetent general, unscrupulous politician, or partisan editor. A New York private scorned the “chuckle heads at Washington” who kept replacing one failed commander with another.64

In the rough calculations of the common soldier, the war was simply no longer worth its staggering cost. The most disheartened men demanded peace on virtually any terms. Brave soldiers blamed skulkers, deserters, and all the disaffected folks at home for taking the fight out of many regiments. Why continue the slaughter, a Pennsylvania sergeant in Meade’s division asked, when “pen and ink” could settle the entire matter?65

But the Army of the Potomac had already survived command changes, several disasters, and numerous prophecies of its imminent collapse. This is not to deny that the morale crisis was real or serious; it was. Yet even among fellows who cursed incompetent officers and railed against Copperheads, there remained a spark of hope, if not exactly optimism. These soldiers often despaired of their own government but not of their comrades, men who had stood the fire before and who would not shrink from it next time. Honor, now often defined as one’s reputation in the company or regiment, would keep such men in the ranks. A fatalism about death coupled with the conviction that suppressing the rebellion required more fighting steeled them for the spring campaign. As a Massachusetts lieutenant rightly observed, the army had been somewhat demoralized ever since spring when it had been thrown back from the gates of Richmond but had fought well anyway.66

In a long letter explaining to his wife why he stayed in the ranks, Cpl. Peter Welsh of the Irish Brigade recaptured this spirit of hard-headed yet still idealistic patriotism: “This is my country as much as the man that was born on the soil and so it is with every man who comes to this country and becomes a citezen.” Even a war filled with “erors and missmanagement” carried a “vital interest” for “people of all nations.” Anticipating Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Welsh defined the stakes:

This is the first test of a modern free government in the act of sustaining itself against internal enemys and matured rebellion[.] all men who love free government and equal laws are watching this crisis to see if a republic can sustain itself in such a case[.] if it fails then the hopes of millions fall and the desighns and wishes of all tyrants will suceed[.] the old cry will be sent forth from the aristocrats of europe that such is the common end of all republics[.] the blatent croakers of the devine right of kings will shout forth their joy.... It becomes the duty of every one no matter what his position to do all in his power to sustain for the present and to perpetuate for the benefit [of] future generations a government and a national asylum which is superior to any the world has yet known.67

Perhaps better than any other statement from a common soldier, Welsh’s tribute to American democracy explained how the Army of the Potomac would survive to fight another day.

That very question, however, still hung fire, especially with the northern public. The effects of the Fredericksburg campaign had shaken the Union’s already wobbly foundations. The gloom in Washington was not lifting. Despair visited everyone from sober moderates, such as Senator John Sherman of Ohio, who believed that “military affairs look dark,” to excitable radicals, such as Horace Greeley, who warned that the country stood on the “very brink of a financial collapse and a Copperhead revolution.”68

Yet in the cities and elsewhere, despite scores of families in mourning for men recently killed, what one Philadelphia editor termed the “pleasure-seeking population” appeared “gayer than they ever were.” It was a central irony of this war, indeed of many modern wars: “People are making money so fast they can afford to spend it freely.” No wonder soldiers had grown discouraged, the wife of Michigan’s Republican governor noted, “when people living in comfortable homes who have not paid a cost or given up a friend” were constantly “harping” about every real and imagined difficulty.69

There was nothing imaginary, however, about the general malaise. Loneliness, cold, bad food, disease, death, and the sheer boredom of winter quarters left both armies languid. In the face of chronic shortages of everything from horses to shoes, the Rebels exuded confidence, although thoughtful southerners recognized Confederate weaknesses. Democrat Horatio Seymour unnerved Republicans throughout the North even as the moody, mysterious Lincoln appeared more decisive. In both the United States and the fledgling Confederate nation, conscription threatened to pit neighbor against neighbor by raising the most basic and explosive questions about power and justice. Nervous Europeans read about the American bloodbath with both fascination and horror.

As some families struggled to make ends meet, their soldier boys also had to weigh the costs of war in the balance of their own commitment to cause and comrades. Reservoirs of patriotism remained substantial but not inexhaustible. For those with a metaphorical turn of mind, the men stuck in the muddy camps symbolized a nation mired in civil war. The cold and muck of winter—the season of death—provided a setting to match the gloom, particularly for the Federals. Yet also for reflective Confederates, including the poor people driven from their ruined homes in Fredericksburg, who understood that the Yankees were far from whipped, optimism could not always chase away darker thoughts. All across the fractured land, hard questions about the Lord’s will and nagging fears about the future seemed as natural as the bare trees and fallow fields. Peace remained a distant, indistinct, and elusive dream.