Epilogue

On December 28, 1862, a Fredericksburg woman refuging in Richmond finally learned what fate had befallen her property. Her home had been commandeered as a temporary hospital, and the parlor table had been used for amputations. Blood and water still filled cups and vegetable dishes, and a Union soldier had been buried near the kitchen door. This was but one example of the desecration and destruction that returning Confederate soldiers sadly cataloged after the Yankees withdrew from the town. Besides fire damage on some blocks and innumerable shell holes in various buildings (at least twenty in the steeple of St. George’s Episcopal Church), minié balls had peppered doors, and fences had been knocked down all over town. Furniture, clothing, trunks, and books, along with valuable business and family papers, still littered the streets. A Charleston newspaper correspondent angrily reported how the Yankees with their “muddy boots and jingling swords” had turned the once “elegant library” and the fine furnishings of the Bernard House into a bedlam.1

The physical destruction drove home the connection between the material concerns of daily life and the abstract world of ideology. The loss of food, clothing, shelter, and even privacy made the struggle against the Yankee invader much more tangible. Understanding the soldiers’ suffering had become much easier for refugees still camped in the woods or sleeping in outbuildings.

The Federals’ departure had not brought much relief to the people of Fredericksburg, nor had it even ended the looting. Although with less thoroughness and alacrity, Confederate soldiers, too, snatched up provisions and souvenirs. One local resident feared that the Rebels would likely take whatever the Yankees had left behind. “It is as you know,” a bank employee lamented, “the fate of war and I must submit without a murmur.” Deserted buildings offered too many temptations. “The conduct of our soldiers is most disgraceful,” another citizen admitted, “and yet we must be silent for fear of giving encouragement to the enemy. To the dwellers on the frontier, civil war is no pastime.” Much of the nearby countryside had already been devastated, and a sensitive Georgia captain observed, “These people have felt the pang of War in every sence form or Shape.”2

Many civilians had heard the sounds of battle, assisted the wounded, and even donated nails for making coffins. Over the next several weeks refugees would drift back into Fredericksburg, some with toddlers or babies only days old. A Mississippi infantryman worried that these “pitiful” children would not enjoy “much of a Christmas celebration,” and neither would their parents. Some families had lost nearly everything; others went hungry. The social order showed signs of collapse. Not only had many slaves run off to the Yankees, but the ability to rely on friends and neighbors seemed to be crumbling as fast as the ruined buildings. Genteel families once known for their beneficence no longer had much to share with the destitute.3

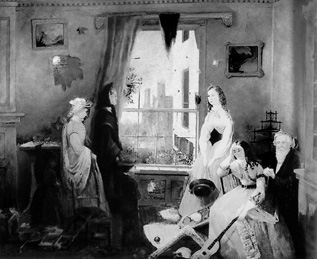

David English Henderson, The Return to Fredericksburg after the Battle (Gettysburg National Military Park)

Refugees daring or desperate enough to return while the Yankees lurked across the river entered a world of destruction. The town’s elite had lost everything from fancy French beds to valuable artwork, but ordinary people, too, found their furniture broken up and their crockery smashed. Even people fortunate enough to recover household goods and find new lodgings often could not meet the exorbitant living expenses.4

General Lee’s “acute grief” for women “flying from the enemy” had been somewhat assuaged by “the faces of old and young . . . wreathed in smiles and glow[ing] with happiness at their sacrifices for the good of their country.” Lee, more familiar with upper-class women who entertained dashing officers at candy stews, expected “a kind Providence” to protect these noble people. Other soldiers met less-idealized specimens, poor mothers looking for lost children or begging for food.5 Angry excoriations of the Yankees would not succor the destitute, whose ideas about patriotic sacrifice (or even divine protection) had been radically altered.

Their plight, however, also elicited a more practical response. After the battle Confederate regiments and brigades took up collections. Typically officers chipped in about $10 apiece, and privates, despite their low pay, gave an extremely generous dollar or two. Generals and even a few enlisted men gave $100 or more. Regiments generally raised around $500; some brigades, over $2,000. One of Jackson’s staff officers claimed that $30,000 in donations had reached corps headquarters.6 The soldiers appeared to be cheerful givers, and newspapers heralded their selfless devotion to suffering women and children.7

Helping the Fredericksburg refugees became a test of patriotic fervor for southern civilians as well. Beginning in Virginia, then spreading south and west as far as Mobile, local aid associations began raising money for what a Georgian described as “people rendered homeless by the Northern vandals.” Anti-Yankee invective spiced pleas for generosity from people living in communities as yet untouched by the invaders. Women from ladies’ relief groups fanned out from church meetings into the towns and countryside; some went door-to-door soliciting neighbors and friends.8

The combined donations from civilians, soldiers, and even city councils reached an impressive $170,000. Individuals and churches sent flour, bacon, and other provisions to hungry families near Hamilton’s Crossing. Newspapers printed lists of contributions; 50 cents became the Confederate equivalent of the scriptural widow’s mite. Slaves in the Army of Northern Virginia reportedly made generous, voluntary donations to the cause. “There’s an item for the Northern freedom shriekers,” a newspaper correspondent smugly remarked.9

But the imposing amounts raised hardly dented the overwhelming need. Throughout late January and February applications for assistance poured into Mayor Slaughter’s office. One woman whose family had already received $100 in public money had not yet been able to replace all the groceries that had been stolen or spoiled. There were still mothers whose children had little clothing left and were nearly barefoot. Even refugees who had not yet returned to Fredericksburg begged the mayor for money to meet the skyrocketing costs of room and board. By March, Slaughter was again appealing for contributions. He praised the uncomplaining people of Fredericksburg, who had suffered heavy losses and remained steadfast in the southern cause.10

Slaughter exaggerated both the virtue and the unity of his community, yet the town’s citizens had, in fact, paid a high price for loyalty—a price they would pay throughout the war years and beyond. Periodic threats from Yankee armies kept refugees from returning, and as late as October 1864 there were no more than 600 to 800 people in Fredericksburg. Signs of destruction remained after Appomattox. The Lacy House that had served as Sumner’s headquarters stood deserted, its windows smashed, rooms filled with rubbish, and the names of Yankee soldiers scrawled on the walls. Visitors still noticed artillery damage in several town buildings. Eventually fields and orchards would cover up battle scars, but the stone wall still stood as a mute, austere reminder of almost unimaginable carnage. Local residents loved recounting how the Yankees had been beaten back time after time on that long-remembered December day, a signal victory in a disastrous war. By the 1870s, physical signs of the fighting had largely disappeared, but atop Marye’s Heights stood a national cemetery, the ironic, final resting place for many Federal soldiers who had fruitlessly tried to reach that ground during the battle.11

* * *

Union soldiers understood how the destruction of Fredericksburg had made some Confederates fight all that much harder. For these men connections between the ordinary rhythms of daily existence and a willingness to risk one’s life had always been at the heart of soldiering. Like all great battles, Fredericksburg had brought together the ordinary and the extraordinary. The common elements of material existence—food, clothing, and shelter—had shaped and, in turn, been shaped by the higher ideals of the flag, the Union, and freedom as well as more basic loyalties to a company or that friend standing next to you in the battle line. Human beings experience the ephemeral and the enduring simultaneously, which is why military campaigns involve much more than strategy, tactics, or horrific combat. Soldiers are more than fighters, and civilians are more than citizens. Bodies, minds, spirits: all become part of the story of war. This war in particular involved both revolutionary upheaval and the very human efforts of ordinary people somehow to hang on to the comforting and familiar even as the foundations of their lives appeared to be cracking and giving way. That cemetery on Marye’s Heights, of course, literally marked the end of the story for so many young Americans.

In quite different ways the Confederate refugees and the rows of graves (mostly for unidentified soldiers) epitomized the suffering that had become synonymous with the word “Fredericksburg.” But they could hardly encompass the lasting anguish the battle had spawned. Soldiers fortunate enough to survive serious wounds usually endured painfully slow and uncertain recoveries. After having his left leg amputated, in April 1863 Sgt. George Zuelch of the 7th New York still languished in a Washington hospital suffering pain, fever, and nausea. He would not be discharged for yet another thirteen months.12

But at least Zuelch’s wound finally healed. Pvt. Andrew Cole of the 145th Pennsylvania had beaten the odds to survive removal of bone fragments from a skull wound (trephining). He was mustered out of service in December 1863; but in February 1864 the wound was still “open and discharging,” and in all likelihood more bone would have to be removed. For other soldiers, too, old wounds remained swollen, saved limbs were useless, and pain was chronic.13 After being shuffled from hospital to hospital and finally sent home, many veterans were left permanently, sometimes completely, disabled. A New Hampshire volunteer whose wound no longer troubled him eventually succumbed to the diarrhea contracted in camp. A Vermonter in the Sixth Corps who had been hit in the intestines and bladder managed to get along with a “urinary fistula” and “artificial anus,” yet he died at age twenty-five only six years after he left the army.14

For such men the anguish of the battlefield had never gone away. The screams of the wounded echoed in their own cries of pain. The blood lust of combat, a raging, almost blind fury that often had little or nothing to do with causes or comrades, had produced horrific injuries. It might take years to repair the damage even partially. Some veterans endured several postwar surgeries, often because of hasty or botched amputations. A Pennsylvania private who lost a big toe to gangrene had to face another amputation in 1867 and still another the following year. He ended up losing two-thirds of his right leg. On three occasions between 1872 and 1874 a doctor examined an ex-private from the 7th Michigan who had undergone an amputation at the right ankle joint. Since the ends of the bones sometimes painfully extruded and discharges from the stump persisted, he recommended an amputation at the knee, though the records are silent on whether the hapless sufferer agreed to go under the knife again. But even saving a leg might also mean losing it, or worse. A New York corporal in Caldwell’s brigade had been hit in the right femur during the skirmishing of December 14. A surgeon removed the ball, but the fractured limb was badly deformed. Bone fragments were extracted several times, and in June 1865 an amputation was performed at a New York hospital. After apparently improving, the man died in early October. Complications from amputations, abscesses, and pain dogged veterans’ lives long after the war.15

Orators, poets, and writers of monument inscriptions eulogized the dead of Fredericksburg but ignored the badly wounded survivors for whom the battle remained a daily, tormenting memory for the rest of their lives.16 Young people would later recall seeing the aging veterans marching in parades, living reminders of that glorious and terrible war; the private agonies of helpless fellows dependent on families or institutions seldom came into public view.

* * *

In many ways Fredericksburg had woven together the mundane, the horrific, and the transcendent. Everyday matters such as shelter, clothing, food, pay, and letters had loomed larger for the common soldiers than campaigns or strategies. Yet generals’ plans along with privates’ fears and junior officers’ ambitions had influenced the pace and texture of military life. Bloody combat occurred in the context of family news, politics, ideology, religion, and rumor. It tore at emotions, often undermining or solidifying faith in leadership and the respective causes.17 The approach of winter, dampness, smoke, rain, and mud had shown how a campaign encompassed much more than lines on a map, shifting batteries, or advancing brigades. Everything from shoe shortages to supply foul-ups to cavalry raids added to the miseries and anxieties of soldiers in the field.

The military significance of the battle loomed enormous at the time but has since been overshadowed by engagements such as Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness. Yet because it was fought between the fall elections and the final Emancipation Proclamation, Fredericksburg exemplified Clausewitz’s famous dictum about the connection between warfare and politics. The replacement of McClellan the political lightning rod with Burnside the political innocent had clearly reflected Lincoln’s frustrations with generals who offered unsolicited policy advice without winning victories.

Burnside’s initially rapid advance, however, had been foiled by poor planning in Washington, the pontoon delays, and his own unrealistic assumptions. As an army commander Burnside often lacked the flexibility to change either his strategy or his tactics in the face of new information or enemy movements. Both the location and the timing of the river crossing, after several delays, proved anew that coordination of movements and accurate intelligence had become crucial in maneuvering large armies—principles further illustrated by the reassembling of Lee’s forces along with skillful defensive preparations on the Confederate left and the flawed alignments on the Confederate right. Given the natural strengths of the Rebel positions, however, Lee clearly had a lot more margin for error than Burnside.

Indeed, in hindsight it appears that the Federals could hardly have selected a worse place to fight, and any gains they might have achieved would have been short lived and costly. Yet the fighting had proved indecisive. As was typical of Civil War battles, the victors could not follow up their success. Staggering losses and a terrible defeat for the Federals yielded only modest gains for the Confederates. Longstreet may well have learned about the advantages of the tactical defensive, and Federal generals would certainly become more reluctant to order frontal assaults against well-entrenched troops; but whether such “lessons” would be effectively applied to the advantage of either side remained much in doubt. Few, if any, generals could effectively manage and maneuver forces as large as the armies at Fredericksburg. A truly decisive victory would have required nearly flawless coordination and execution, but inadequate staff work, cumbersome command structures, and the chronic shortage of capable corps, division, and brigade commanders all meant that by the spring of 1863, it appeared that neither side could win the war on the battlefield—at least in the eastern theater. The battle of Fredericksburg marked the continuation of a military stalemate, an already well established pattern that greatly discouraged Lincoln and the northern public just as it satisfied but also frustrated the Confederate leadership.18 In that sense the bloody battle whose results created powerful political reverberations was almost strategically insignificant.

The memories of Fredericksburg, however, would naturally focus on the extraordinary, the spectacular, and the terrible. The attempts to lay the pontoons in the heavy fog, the stout Confederate resistance, the deafening artillery bombardment, the hazardous crossing of the first Federal troops, the sharp street fighting, and the sack of the town had become striking features of the campaign before most of the troops on either side were even engaged. The tactical complexities of Franklin’s attack and Jackson’s counterattack were overshadowed by the repeated and senseless charges by Sumner’s and Hooker’s men toward the stone wall. The deadly Confederate artillery and withering infantry fire would not be soon forgotten by Yank or Reb.

Nor could anyone ignore the tenacity and futility of the attacks. Burnside’s well-executed withdrawal from Fredericksburg could not for a moment atone for the bloodletting that came to define the battle in many people’s minds. Staggering casualties, hasty burials, numerous amputations, and a painful struggle to find meaning in seemingly vain sacrifices all cast long shadows over the Federal camps, though even the victorious Confederates had to contemplate the high costs of war. From the hospital tents in Falmouth and the wards in Richmond and Washington rose the stench of blood, sweat, piss, and death. Depressing news reverberated throughout both “nations,” back and forth between camp and home, and sent shock waves that echoed in Europe. The triumphant Rebels flirted with overconfidence even as the whipped Federals indulged in seemingly endless rounds of recrimination. On a more abstract level, both sides staked out a variety of positions on such burning issues as slavery and freedom, but for the soldiers, especially for the bluecoats, the realities of cold, disease, desertion, and mud often obscured these larger questions. Yet the most tangible and persistent kinds of suffering, including memories of slaughter and sacrifice, and even the agonies of the Mud March, could not overwhelm human resilience.

Some men still found strength in their religious faith, others in fighting for their families or even for a cause, though for many veterans in both armies Fredericksburg came to symbolize a raw courage that the home folks could never quite understand. Soldiers knew that bravery—displayed for all to see in the word “Fredericksburg” soon to be emblazoned on regimental flags—exacted a terrible price, and that despite all the grumbling, disillusionment, disaffection, and even desertion, many had, however reluctantly, paid the price. At the dedication of a monument to Humphreys’s division in the National Cemetery at Fredericksburg on November 11, 1908, editor and political wheelhorse Alexander K. McClure compared the valor of his fellow Pennsylvanians to the courage of Pickett’s men at Gettysburg. Sectional reconciliation had become a major theme on such occasions, and as a noncombatant McClure hardly carried the moral authority to describe much less assess what these men had endured. But by this time many old soldiers themselves had noted the obvious parallels between the two engagements. Humphreys’s men had long been convinced that their gallantry had been unequaled during the war, but when they shook hands with some of Pickett’s veterans, a former private in the 129th Pennsylvania decided that “although these two divisions failed in what they undertook they showed the stuff of which the American soldier is made.”19

Several former bluecoats believed their bravery superior because they had made more assaults. They also liked to quote Lee, who after the war had supposedly praised the intrepid spirit of the Irish Brigade and other Union outfits at Fredericksburg.20 Even on that hot July 3 in Pennsylvania, some Confederates recognized that they had experienced their own “Fredericksburg”—a word that evoked images of desperate and futile struggle. Over the years some ex-Rebels conceded that Federal attacks at Fredericksburg had set a standard for valor and persistence that even Pickett’s charge had not matched.21 Such claims rested on glittering and surprisingly bloodless generalities. In their recollections, the details of the physical anguish, political turmoil, factious backbiting, and spiritual doubts were obscured. But then the aging survivors likely had a perspective different from that of the young men in both armies who had stood their ground, faltered occasionally, cursed their fate, called on God to save them, and finally fallen on that harrowing thirteenth of December.