5. ‘I shall be an autocrat: that’s my trade’

Timeline

| 1725 | Death of Peter the Great Coup by Catherine I |

| 1741 | Coup by Elizabeth |

| 1762 | Coup by Catherine II the Great |

| 1767 | Convening of the Legislative Commission |

| 1768–74 | Russo-Turkish War |

| 1773–4 | Pugachev Revolt |

| 1783 | Annexation of Crimea |

| 1785 | Charter to the Gentry |

| 1787–92 | Russo-Turkish War |

| 1788–90 | Russo-Swedish War |

| 1796 | Death of Catherine the Great |

ENGLISH CARTOONISTS TOOK NO PRISONERS when they lampooned the public figures of the day, but while not an especially flattering representation of Russian Empress Catherine II – Catherine the Great – it is in many ways a mark of Russia’s new status. In a dig at her ambitions to challenge the Ottoman Empire, here she is striding in one step from Russia to Constantinople, while below her the spiritual and secular lords of Europe express their ribald admiration. ‘Never saw any thing like it,’ says Louis XVI of France, and ‘What a prodigious expansion’ swoons England’s George III. The Ottoman Sultan sighs that ‘The whole Turkish Army wouldn’t satisfy her.’

Cheap shots at her (largely mythical) sexual appetites aside, what is noteworthy is firstly that Catherine is represented not as some exotic Asiatic monarch, but a wholly European one, a culmination of the process begun by Peter to bring Russia back into the West. Secondly, while Russia never did manage to take Constantinople, the thought of it doing so was considered entirely possible. Russia was no longer of negligible significance and distant bearing, but part of the fractious European family of nations.

After all, Catherine the Great (r. 1762–96) did more than just shape Russia’s eighteenth century, she also shaped its image and place in the world. In that, she was in many ways what today we might call a mistress of spin. She expanded and blinged out the Winter Palace in St Petersburg to rival the grandeur of the French monarchs’ Versailles. She kept up a spirited correspondence with the philosophers of the day, notably Voltaire, even while holding them safely at arm’s length so they could not see how many of her claims about Russia were simple hype. At a time when the country was being squeezed to support war against the Ottomans, she told Voltaire that ‘our taxes are so low, there is not a peasant in Russia who does not eat chicken when he pleases’. She was indeed a reformer, and sought to bring culture and literacy, progressive policies and sound laws to the country. Catherine was the very image of that eighteenth-century European ideal, the ‘enlightened despot’, dragging countries into the future by the power they inherited from the past.

Arguably, though, the more she tried to turn Russia into a European nation, the more she brought forth some unavoidable contradictions in the design. Catherine’s golden era was in many ways to prove nothing but gilded brass, a thin patina of European culture over a nation that was increasingly falling behind and away from the courts, factories, shipyards and universities of the West. One of her favourites, Grigory Potemkin, was said to have built fake villages to give an impression of cheery plenty for a visiting Catherine. This is probably something of a fable, but ultimately Catherine’s Enlightenment Russia was a ‘Potemkin nation’, trying too hard to persuade everyone else – and itself – that it was something it was not. It would take an upstart Corsican artilleryman truly to puncture many of the myths of eighteenth-century Russia, when Napoleon smashed across Europe and into its lands.

Fundamentally, after all, the country was still mired in the Middle Ages socially and economically. The overwhelming majority of the population were peasants; most serfs working on land owned by the state, aristocrats or the church. This would scarcely change over the century: 97 per cent lived on the land in 1724, 96 per cent in 1796. Serfs were chattels, who could be sold or transferred around the country as family units, and had no claim to the land they worked. Although some token attempts had been made to introduce Western farming methods, these had not accounted for much, sometimes because the heavy soils and hard climate did not allow, but often because of a lack of skills, training, investment capital and interest, so agricultural productivity was still close to medieval levels.

Domestic and international trade did grow, especially as Russia gained ports on the Baltic and Black Seas, and with it a mercantile class began to emerge, but it was very small. Peasant traders handled much small-scale domestic commerce, and foreigners and noblemen much of the rest. The state would be in a permanent financial crisis through the century, tax collection never keeping up with expenditures on wars, prestige building projects and the court, and having to fill the gap with promissory notes and printing money. While the state bureaucrats and richer nobility were literate and becoming exposed also to foreign ways, many of the rural gentry could often neither read nor write. This was hardly the country Catherine the Great would sell to the West.

A Time of Empresses

Russia, so traditionally chauvinist, was about to have to get used to women being on the throne. When Peter died in 1725, he had on the one hand established the principle that a tsar could name his successor (from his family), but on the other failed actually to nominate anyone. He had previously declared his second wife, Catherine, as tsarina, empress, but it is questionable whether she could have taken power simply on that basis. Instead, she was considered a suitable figurehead by a cabal of figures who had risen under Peter, led by the shrewd but deeply corrupt Prince Alexander Menshikov. Calling on the Guard regiments – who not for the first time would prove kingmakers, or in this case empress-makers – they installed her as Catherine I (r. 1725–7) in a virtual coup d’état, fearing that otherwise traditionalists from the older boyar families would simply return to power.

She had two daughters of her own, but Russia was not ready for a matrilineal descent, and so Catherine had to assent to the naming of the only male-line grandson of Peter I as her heir. When she died in 1727, the 12-year-old Peter II (r. 1727–30) was duly crowned, the ubiquitous Prince Menshikov acting as his regent. Fate, though, seemed disinclined to let this sexism pass, and he died a mere three years later, leaving no male heirs. The next in line would have to be found from the children of Ivan V, Peter’s co-tsar, and this meant either the eldest, Catherine, or her younger sister, Anna. Like it or not, the Russians were going to have another empress.

While Catherine was older, she was married to a German, Karl Leopold of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, whom the boyars feared would seek to exert influence over Russia if his wife became tsarina. Instead, the Supreme Privy Council, the body that had replaced the Boyar Duma, opted for the widowed Anna. As with Catherine, though, the intention was that she was to be a figurehead. Prince Dmitry Golitsyn, chairman of the Council, presented her with a set of ‘Conditions’ that she was expected to adopt. They discovered it was easier to demand obedience than to enforce it. Once crowned, Anna (r. 1730–40) tore up the ‘Conditions’ and dismissed the members of the Council, filling it with more agreeable candidates. Golitsyn would end up dying in prison, and while he has since been celebrated as a man who tried to bring constitutional rule to Russia, one can wonder whether this was really out of principle or simply because he thought this was his chance to be the power behind the throne.

Ten years later, close to death, Anna made her two-month-old grandnephew, another Ivan, her heir, appointing her German lover, Ernst Biron, regent. This was an attempt to secure both Ivan V’s bloodline and also Biron’s future. She had never been a popular figure, though, and her tendency of filling the court with German relatives and cronies had alienated populace and boyars alike. Ivan VI (r. 1740–1) was crowned, but within three weeks Biron had been banished to Siberia, and just thirteen months after his coronation, the unlucky child-tsar and his family would be imprisoned in a fortress in Russian-controlled Latvia after a coup by Elizabeth, daughter of Peter. Ivan V and Peter had managed to coexist as monarchs, but their bloodlines were seemingly locked in war.

Energetic, intelligent and charming, Elizabeth had won over the elite Preobrazhensky Regiment, and in 1741, they seized the Winter Palace, Ivan and the throne for her in one bloodless night. The 33-year-old Empress Elizabeth (r. 1741–62) ushered in an era of elegance, extravagance and diplomacy. Russia became ever more present as a major European power. A war with Sweden was ended, with Russia taking southern Finland, while it became a key player in the Seven Years War (1756–63) against a rising Prussia. In 1762, Frederick the Great of Prussia was on the verge of defeat when news came that Elizabeth had died. Childless, and desperate to keep Peter the Great’s bloodline on the throne, the only heir she could choose was her nephew, Peter of Holstein-Gottorp. German-born, even though Elizabeth had tried to ensure he had a Russian education, scarred by smallpox and obsessed with toy soldiers, Peter III (r. 1762) would only reign for 186 days. However, his elevation crucially opened the door to the Winter Palace to his wife, Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, who would be known in history as Empress Catherine the Great.

From Sophie to Catherine

Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg was born to Prussian German aristocratic stock of considerable connections but relatively little fortune. As was the fate of girls in such circumstances, the expectation was that she would be married off for the good of the family, regardless of her own inclinations. Certainly the choice of her second cousin, Peter of Holstein-Gottorp, owed everything to politics and nothing to affection. Peter’s aunt, Tsarina Elizabeth, was eager to build ties to Prussia, and Sophie’s ambitious, manipulative mother was enthused by the prospect of a daughter on the Russian throne and a chance to spy for Frederick II of Prussia (she was eventually banned from the country for that very reason).

At age 15, Sophie travelled to Russia. Peter she found obnoxious, but she neither had much choice in the matter nor was she unaware of the opportunities for an otherwise impecunious young Prussian princess. It hardly hurt that Elizabeth clearly took a shine to her. So in characteristically enthusiastic style, Sophie threw herself into learning Russian, was baptised into the Orthodox faith with the Russian name Yekaterina – Catherine – and married Peter in 1745.

Peter did not improve on closer acquaintance and the two of them lived largely separate lives, taking lovers and pursuing their own interests. Peter loved to play with both toy soldiers and real ones, putting his servants through an elaborate and demanding drill of a morning. The vivacious and shrewd Catherine, by contrast, actively courted the all-important Guard regiments. When Peter III ascended the throne in 1762, he managed in short order to make himself even more unpopular, not least by prematurely withdrawing from the war with Prussia (he was a great admirer of Frederick the Great, even referring to him as ‘my master’).

The irony was that the German tsarina Catherine seemed more loyal than the Russian-blood Tsar Paul. Having endured seventeen years of marriage to the man, she was clearly prepared to seize the opportunity to rid herself of him, though, and take his place. While he was spending time with his relatives in his country estate, Catherine was back in St Petersburg, plotting. Resplendent in a guards’ uniform, she visited the Izmailovsky and Semyonovsky regiments and appealed to them for their support. She had the church on side, she had key figures within the government on side, and she had the Guards. Peter was arrested and forced to abdicate, and shortly thereafter was killed, and Catherine II (r. 1762–96) was empress.

As usual, history, tradition and ritual were scoured to justify political pragmatism. Fortunately, a tenuous path could be tracked through Catherine’s genealogy to the Ryurikid dynasty, and Catherine I’s example of succeeding Peter the Great, however questionable at the time, now became considered precedent. Although there would be occasional word of conspiracies – and more serious threats from risings in the countryside – Catherine would remain firmly in power until her death.

Educated, intelligent and coming from the more cosmopolitan European nobility, she was committed to reform as a means of raising Russia to Western levels. If Peter the Great’s real focus had been military, and the state-building measures this demanded, hers was cultural and intellectual, and the programmes that flowed from this. In Europe, this was the era of ‘enlightened despotism’, of autocratic rulers who claimed to be inspired by the Enlightenment values of reason, scientific process, freedom and tolerance, and to rule in the interests of their people. Often, this actually proved to be more about despotism than enlightenment, and Catherine herself famously said, ‘I shall be an autocrat: that’s my trade.’

Nonetheless, she also had a clear enthusiasm for presenting herself and her country as a European power, at the forefront of the Enlightenment. Western fashions and culture became de rigueur at her cripplingly lavish parties and celebrations (by 1795, over an eighth of the total state budget went on court expenditures). Just as hiring Dutch and English shipwrights did not modernise Russia overnight, though, nor did corresponding with European philosophers and buying Western art collections reshape the nation. To be honest, her reputation was not as much about what she did, but what she wrote, and what others wrote about her.

Empty Enlightenment?

That did not mean Catherine did nothing. Quite the opposite: this was a time of considerable progress and change. Foreign books once banned or ignored were translated, and vaccinations against smallpox introduced over the complaints of many. She espoused religious tolerance (while at the same time seizing the last of the church lands) and ended the use of torture (in theory). Although grandiose plans to provide universal education predictably came to nothing – not least because peasants could see little point in it – her reign did see an expansion of schools and universities, with even some women being admitted.

Yet there was a void at the heart of her programmes. She seemed genuinely to believe in the importance of liberty and law, which to be meaningful have to constrain the state and the monarch. But she was also an unabashed autocrat, unwilling to brook protest or dissent. Was she serious about legality and reform, or just playing a role? In 1766, for example, she called a Legislative Commission that was to be made up of representatives of the aristocracy, gentry, townspeople, state peasants and Cossacks – not the serfs – to consider a new code of laws. They were presented with Catherine’s Nakaz, an ‘Instruction’, being a 22-chapter statement of the principles she wanted embodied in this code. She had worked on this document for almost two years and although she heavily and often word-for-word cribbed from the French philosopher Montesquieu, the Italian jurist Cesare Beccaria and other European thinkers, it nonetheless is an impressive and progressive treatise, which marries a continued commitment to absolutism with progressive notions of equality and legalism.

However, when the commission met the following year, it became clear that this haphazard collection of boyars and burghers, soldiers and squires, clerks and Cossacks, was unqualified, disunited and unsure of its mandate. It met 203 times and discussed everything from nobles’ privileges to merchants’ rights, but failed to reach any conclusions or make a single recommendation. Eventually, after the Russo-Turkish War broke out in 1768, it was suspended and never recalled.

But does that mean it was wholly pointless, nothing more than an exercise in cosmetic constitutionalism? Not quite. First of all, Catherine cannot be wholly blamed for its impotence. This was an experiment in consultation, and as much as anything else an opportunity precisely to see if there was any consensus in the country. (There wasn’t.) It also gave her new insights into the priorities and concerns of social groups that otherwise rarely got to have their views heard, views that did make their way indirectly into much future legislation. It also brought in representatives of the petty rural gentry, who often didn’t stray far from their estates except when called upon in war. This reminded the boyars (the term persisted for the more powerful aristocrats) that there were alternative power bases to which Catherine could appeal.

Power and Purpose

After all, behind all the grandiose rhetoric about egalitarianism was a crucial renegotiation of power between the state and an aristocracy that still dominated the army, the civil service and the countryside. They were not investors with wealth in stocks and shares, nor were all in government service. Rather, their wealth was still based on land, and the peasants and serfs who worked it, and so serfs had to remain serfs. As empress, Catherine herself owned half a million of them, and the state another 2.8 million. She gave them more rights to petition local governors if their masters abused them, but meanwhile she also gave the landowners the right to exile serfs to Siberia; win some, arguably lose more.

In his blink-and-it’s-over reign, Peter III had issued a barrage of new laws and decrees, including the ‘Manifesto of the Freedom of the Nobility’ that further ate into the service obligations of the nobility. In its words, ‘no Russian nobleman will ever be forced to serve against his will; nor will any of Our administrative departments make use of them except in emergency cases and then only if We personally should summon them.’ A cynic might suggest a weak man in a weak position had been trying to buy himself the support of the Russian aristocracy. In any case, Catherine – presumably also mindful that a monarch elevated by a coup could just as easily be deposed by another – continued this dismantling of Peter’s service state.

In 1785, she went further, issuing her ‘Charter to the Gentry’. This confirmed exemptions from compulsory state service and taxation, sweeping rights over serfs and full hereditary rights to all estates. The gentry were also granted the right to establish their own assembly in each guberniya, or province. In many ways this was classic Catherine: conscription in the guise of concession. She clearly had come to realise that one of the problems with the empire was precisely that it was too focused on a single monarch. She wanted not to weaken autocracy but to make it more responsive and thus stronger by creating intermediary institutions that would handle much day-to-day governance rather than require everything to be run either by St Petersburg or through individually appointed governors with all their temptations to corruption and sloth. That same year, after all, she also granted towns and cities their own charters, building structures of local governance there.

In many ways, this is what was important about Catherine’s era of reforms. Not the vain and vapid correspondence, nor the hollow pledges of Enlightenment values. Catherine may have disliked the death penalty, but she turned a blind eye when the brother of one of her favourites murdered Paul III, and Yemelyan Pugachev, the leader of the largest peasant revolt in Russian history – and who, evoking the False Dmitries of previous eras, claimed to be Paul III – was beheaded and chopped to pieces in Moscow in 1775.

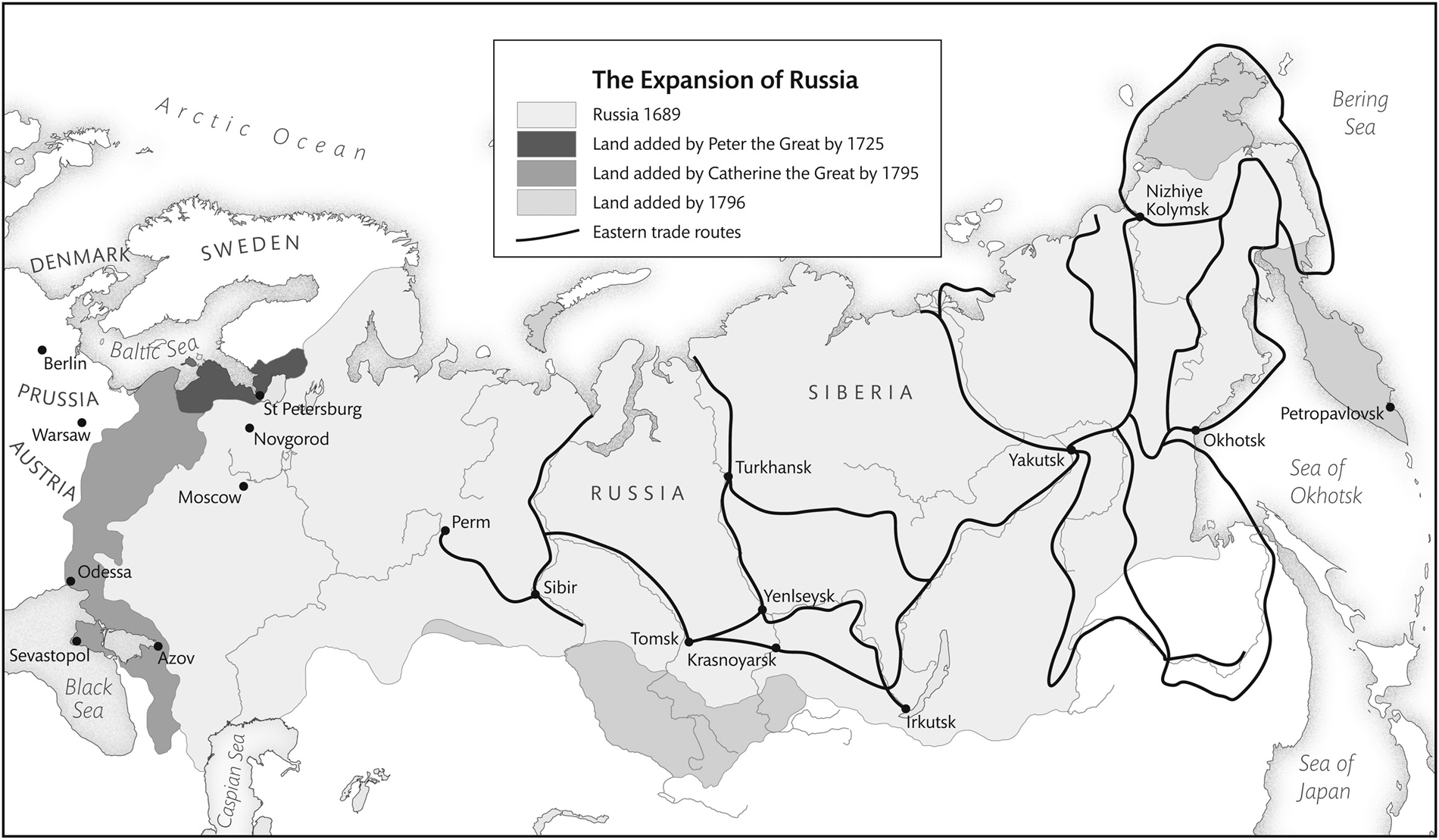

Her foreign policy was equally pragmatic, even if always cloaked in the right, almost apologetic, rhetoric: ‘I have no way to defend my borders but to expand them,’ she claimed. She certainly did that, and Russia’s territories grew by more than half a million square kilometres during her reign. She aggressively warred against Poland–Lithuania, taking part in the three partitions that saw Russia end up with Lithuania and most of eastern Poland. The Ottomans were a particular target, though, as Catherine saw Russia’s greatest opportunities to the south. She never did make that ‘imperial stride’ to Constantinople, but defeated the Turks in the wars of 1768–74 and 1787–92. As a result, she took southern Ukraine, and, in a move that would have historical repercussions for the twenty-first century, annexed the Ottoman dependency of Crimea for Russia in 1783.

At heart, the ‘enlightened despot’ Catherine was more despot than enlightened. Her words in the Nakaz were unambiguous: ‘The Sovereign is absolute; for there is no other Authority but that which centres in his single Person, that can act with a Vigour proportionate to the Extent of such a vast Dominion … Every other Form of Government whatsoever would not only have been prejudicial to Russia, but would even have proved its entire Ruin.’ But she was a smart despot, who understood that the old ways of rule in Russia were increasingly out-of-date. As the ever-quotable empress said, ‘A great wind is blowing, and that gives you either imagination or a headache.’ She undoubtedly had not come up with the answers as to how Russia could change – but she was beginning to ask the question.

After Catherine

Catherine died a natural death in 1796 and was succeeded by her son Paul I (r. 1796–1801). Gossip had questioned whether he was truly Peter III’s son, and Catherine had had little time for him as he grew up. In fact, she seriously considered bypassing him in the succession altogether and declaring his son Alexander her heir. His reign was overshadowed by Catherine’s personality and legend. In what might seem his own form of adolescent rebellion – although he was 42 years old at the time of his coronation – he bucked against an education that was designed to mould him into the perfect Enlightenment reformer and instead espoused an inflexible and authoritarian conservatism.

He hurriedly issued the so-called Pauline Laws, establishing that henceforth the throne would only go to the next male heir in line: no more empresses, no more dangers of someone finding their own son made successor in their place. He made no secret of his disdain for the aristocracy, showering riches on a handful of cronies, and treating the rest with contempt. Like his father he was passionate about the military, but also like his father he had little understanding of real generalship and again indulged in parades and detailed decisions about new uniforms.

The shape of Russia’s military would matter, though. This was the era of the French Revolution, and being both a convinced autocrat and of mystic bent (in 1798, he was elected Grand Master of the Maltese Order of the Knights of St John of Jerusalem), he thought of this in terms of a crusade against anarchy. In 1799, Russia joined Austria, Turkey, Britain and Naples in declaring war on France. The coalition would fall apart, and once Napoleon had made himself ‘First Consul’ in 1799, Paul began talking of a possible alliance with France against the Ottomans. He even drew up plans to send a force off in the direction of British India: to Russia’s aristocratic elite, it looked as if he wanted to take on the world.

He had become dangerous, in a dangerous time, and in the eyes of dangerous men. In 1801, a gang of dismissed officers burst into his bed chamber and tried to make him sign an abdication decree. When he resisted, he was strangled. Did his eldest son, the 23-year-old Alexander, know this was going to happen? All we do know is that he never punished the assassins. Ultimately, though, we know much about what Tsar Alexander I (r. 1801–25) did and said, but it is frustratingly hard to come to terms with who he was. A liberal? A conservative? One of his own mentors, Mikhail Speransky, called him ‘too weak to rule, and too strong to be ruled’. But in many ways maybe it didn’t matter, because his reign would be overtaken by a war with France that would see Moscow burned, Russian soldiers in Paris, and the world changed.

The country would finally have to come face to face with the challenge of reform. Peter the Great had tried to force modernisation from above, and had made some progress but not enough. Catherine the Great had tried to inspire modernisation from above, and had made some progress, but not enough. It was to become clear that real change would have to come from below, and this would prove a terrifying prospect for some, an exhilarating opportunity for others. The opening words of the first chapter of Catherine’s Nakaz were that ‘Russia is a European state’. But in one of her letters to the French writer Denis Diderot, she wrote that ‘you philosophers are lucky men. You write on paper and paper is patient. Unfortunate Empress that I am, I write on the susceptible skins of living beings.’ It was time to see if Russians could not simply be decked out in European finery, or taught to read European books and admire European art. Instead, could they have a European identity – defined in terms of culture and values as much as technology and tradecraft – written on and within their skins?

Never mind the stories Russia told the rest of the world, epitomised in Catherine’s belles lettres to the philosophers of the West. The real question would be what stories Russians would tell themselves about themselves. Peter and Catherine had sought to create narratives that placed Russia in Europe, without necessarily truly thinking through what that meant. They had also told that story to foreigners and to the elites. The slow spread of education and literacy, the emergence of a middle class often looking for its place in the world, influences from the French Revolution to Marxism, all of these would also play their part in ensuring that the nineteenth century was one in which Russia’s identity would be contested more vigorously, and by more players, than ever before.

Further reading: Robert K. Massie’s Catherine the Great (Head of Zeus, 2012) is a massive, benchmark biography, although Simon Sebag Montefiore’s Catherine the Great and Potemkin: The Imperial Love Affair (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2016) is a more fun read. If you do want to read her correspondence, Catherine the Great: Selected Letters (Oxford University Press, 2018), translated by Andrew Kahn and Kelsey Rubin-Detlev, is a good collection, and there are always the Memoirs of Catherine the Great (Modern Library, 2006).