21: A DIFFICULT HEALING

Jorat Dominion, Quuros Empire. Three days since Kihrin D’Mon, Hamarratus, and Star left the Capital in search of a Gatestone

Kihrin frowned.

“I told you that wasn’t my favorite part,” Janel said.

“No, I just had the oddest mental image of watching you kill a demon using someone else’s severed arm.” Kihrin studied her. “But you didn’t describe that. Also, remind me to stay far away from you in a fight.”

“I hardly ever lose control anymore.”

Kihrin shook his head. “Now see, it’s that ‘hardly ever’ part I find so disconcerting.”

“Welcome to the party,” Ninavis said. “At least the beer’s free.”

Janel cleared her throat and looked away for a second. “Your memory of the arm happened. In the Afterlife when we last met.”

“Huh.” Kihrin wasn’t sure how he felt about the idea he was remembering the Afterlife or, by implication, his past life. Unsettling.

Dorna reached over and slapped Qown’s shoulder. “Go on, priest. I wasn’t there for this part. Tell us what happened next.”

Qown’s Turn. Barsine apartment, Atrine, Jorat, Quur.

As Ninavis and Brother Qown carried Count Janel away from the ambush, Qown pondered how much lighter she was than he expected. She took up so much space in a room when awake it was easy to forget her true size.

They had climbed several flights and made their way several buildings over from the ambush site, when they heard shouts and a scream behind them.

Ninavis looked over her shoulder. “Sounds like someone just found the bodies.”

“Stop.”

“We can’t,” Ninavis said. “They’ll chase soon.”

Brother Qown stopped, anyway, and with him, Janel. Ninavis began speaking in a language Brother Qown didn’t understand. He assumed Ninavis was engaging in a graphic description of his ancestry.

“What are you doing?”

“I can’t see,” Brother Qown said. “We left the lantern behind us. I’m worried we’re going to trip over a bench and fall twenty feet. Aren’t you?”

“There’s spill light—”

Brother Qown summoned up a small ball of yellow light. From a distance, it looked like a candle, bright enough to light their passage.

She shook her head. “Hell of a risk. If people notice, they’re not going to stop to make sure you’re Blood of Joras first.” She took the opportunity to reposition her grip on the belt and scabbard holding the giant sheathed Theranon family sword.1 She ended up slinging the whole belt and scabbard over one shoulder, cross-body. “Let’s go.” Her face looked pale, her expression grim. With the fighting over, the shakes were setting in.

She stooped to pick Janel up by the shoulders, while Brother Qown grabbed Janel’s feet. Ninavis and Brother Qown ignored the blood covering them both—Janel’s blood, mostly.

The apartment proved close, although Brother Qown would have missed it without Ninavis’s navigation. To the priest, one windowless corridor looked much the same as any other. But when they reached one—the right one—Ninavis whispered for them to set down their wounded charge. She pulled an iron key from her pocket, unlocked the rooftop gate, and let them inside. Together, they carried the Count of Tolamer into the apartment that had been set aside for the Baron of Barsine.

Brother Qown paid no attention to the decorations or furnishings, except to look for what he needed. That table there. Yes. “Help me put her down on this. On her stomach.”

“Do you need hot water? I can start a fire—”

“Do it. We don’t have much time.” Brother Qown gestured, and the small magical candlelight became a dozen candles, enough to illuminate the room.

Ninavis gaped, mouth open.

“Set a fire,” Brother Qown snapped. “Boil water. Who knows what poison these men used on their bolts?”

“Leumites don’t use poison.”

Brother Qown exhaled, relieved.

“But they do like to dip their arrowheads into dung.”

Something inside him tightened. He bowed his head. “Selanol grant me light.” Brother Qown tried to reach Illumination.

Ninavis stared at him.

He straightened as he pulled a small knife from his belt. “Well? Help me or find Dorna so she can help, but I don’t have time for you to get over your superstitions.”

Ninavis flushed. Her jaw worked, and then she turned, storming to the hearth. She began piling logs from the wood box into the fireplace.

Brother Qown began cutting Janel’s clothing away from the wound. It would have been easier—alas, so many things would have been easier—in the west, where most women wore midriff-baring rasigi. The Joratese preferred full tunics, and those with bosoms tight-laced a reed-strengthened bodice over their chests. It made cutting the fabric away difficult. Frustrated, Qown sliced open the bodice ties and ripped the garment open.

Brother Qown grimaced at the revealed wound.

Ninavis had snapped off the bolt shaft so the injury wouldn’t tear open as they ran, but now he had little choice. The moment he removed the rest of the bolt, the clotted black blood would rip loose, and the bleeding would resume.

Ninavis made a loud noise with something. Something metallic. A cook pot. He looked up.

“So was that because of the curse too?” she asked.

Brother Qown ground his teeth. “I’m trying to concentrate.”

“It was never just her using magic, was it—”

Brother Qown slammed his hand down against the table. “I don’t have time for this! She doesn’t have time for this. Be quiet!”

He didn’t wait on her response. He returned his attention to Janel and once more attempted to shift his vision. He could do this. He had to do this.

This time, Ninavis didn’t interrupt.

Count Janel’s aura appeared unlike any Qown had ever seen before. It twisted and blurred, folding in on itself like smoke buffeted by swirling zephyrs.

An aura that scoffed at his attempts to twist her body back into health.

Brother Qown tried again.

Again, he failed.

He couldn’t heal her. Panic twisted his heart.

Janel had paled from blood loss and shock. If Brother Qown couldn’t find a way to heal her …

If he did nothing, she’d die. The bolt had missed her spine but not her liver. She’d die from that alone, assuming infection and sepsis didn’t claim her.

Brother Qown fished in his robe and pulled out a small metal box.

“What’s that?” Ninavis asked. She must have been watching him the whole time.

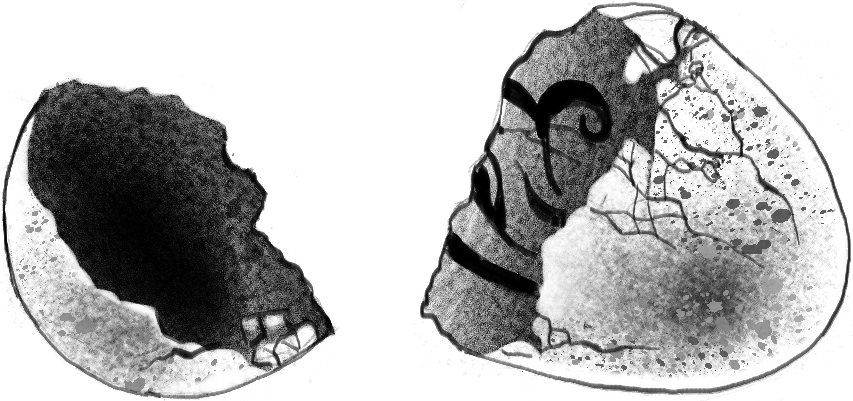

“Desperation,” he said. The priest opened the box. Inside rested a nest of small twigs and feather down. A perfect blue robin’s egg sat in the middle.

Well, it looked like a robin’s egg.

The thin clay had been painted to look like the real thing, as beautiful and fragile.

Brother Qown smashed it to the tile floor, shattering it into countless pieces. “Father Zajhera, I need your help!”

The second stretched out into an eternity. A thousand worries gave birth to a thousand more.

Had the magic failed? Had something happened to Father Zajhera? Was he too busy?

Then the wall began to glow. Its luminance condensed, flowed into shapes and fractals circling each other while the center fell back into nothingness.

“What the—” Ninavis started to say.

Brother Qown remembered to breathe.

“Thank Selanol.”

He’d known Father Zajhera since he was a boy. Father Zajhera, tall and thin and wise. The man who had offered his parents another option besides House D’Lorus, when their son’s mage gift first manifested. He wore his white cloud-curl hair matted into thick strands, held back by bamboo clips, and dressed in robes the same as Qown’s. He looked like a simple monk rather than the leader of an entire religion.

Zajhera read the situation with a glance, dismissed Ninavis as unimportant, and rushed to Brother Qown’s side. “How long ago did this happen?”

“A half hour, perhaps? She’s lost so much blood, and yet she rebuffs my efforts to heal her.”

“I’m not at all surprised.” Father Zajhera pulled the agolé from his shoulders and set it aside. “Let us begin.”

Such a simple thing reminded Brother Qown the Joratese lived in a city they hadn’t built:

Atrine possessed working plumbing.

Even by western Quuros standards, the bathing rooms amazed: beautiful tile work, efficient sewage disposal, sunken wading pools—heated, of course.

He wondered if the Joratese took it for granted. Did they think about it at all? Did the citizens ever stop to marvel at the sorcery that brought fresh water to their apartments, which also bore away their waste? Did some forgotten branch of House D’Evelin maintain the sewer system—or was Atrin Kandor’s enchantment on this city so great it continued to function after centuries? Did the sewage dump into Lake Jorat or the Zaibur River, or did someone do a roaring business selling fertilizer back to the Royal Houses?

Trivial matters such as these filled Brother Qown’s thoughts as he washed his hands.

“She’ll be fine, dear boy. I can see from the look on your face you’re still worried about her.” Father Zajhera stepped through the door behind Qown and presented the priest with a cup of hot tea; Nina’s hot water had served a different purpose.

“I’m worried for her. It’s not just her injury.” Qown took the cup of blue-glazed Kazivar porcelain from his leader’s hands. Qown wondered if the cup had come with the house or if Zajhera had brought it with him. Focus. “I don’t think—” Brother Qown fumbled, started again. “I don’t think I’m the right person to help her, Father. I know how much she means to you. I think sending me to her was a mistake.”

Father Zajhera stared at Brother Qown, who in turn tried not to cringe. Zajhera had a way of looking at people that channeled every parental disappointment ever to sting tears in a child’s eyes. Seeing dissatisfaction in Zajhera’s eyes hurt worse than a dagger’s edge.

“Tell me what happened. Something more, I think, than her injury by brigands.”

Brother Qown motioned for Father Zajhera to follow him, since this wasn’t an appropriate conversation for bathing rooms. They walked downstairs, where a small sitting room offered comfortable chairs and tables upon which to rest their tea.

Ninavis had left to track down Mare Dorna and Sir Baramon. No one else occupied the apartment save for a sleeping count, who would continue her deathlike slumber throughout the night.

“I have followed your suggestions,” Brother Qown said as they both sat down, “and I have avoided discussing the source of her abilities. She has, since I first met her, maintained her strength is due to Xaltorath’s curse. But in recent weeks…” Brother Qown paused to sip his tea. “Well. It’s become difficult to ignore abilities that cannot be described this way.”

Father Zajhera looked surprised. “She’s developed a second spell-gift?” Neither would call it a witch-gift. Witches were not just sorcerers who’d forgotten to pay their license fees.

“With all respect, Father, I believe she has developed a third. You’ve long contended her strength is her own doing, a defense mechanism after the trauma she experienced at Lonezh. I believe the ‘curse’ that sends her to the Afterlife every night is also a spell-gift. And I think she’s beginning to show signs of a third ability involving fire.”

Father Zajhera chuckled. “Impressive. It’s such a shame her grandfather would never let me train her.”

“Of course he wouldn’t. She’s not ‘Blood of Joras.’” Brother Qown gave the other priest a scolding look. “A concept that you never mentioned to me.”

“Hmm? Oh yes. I’d forgotten about that.”

“Well, I’m never going to forget that label. I’m wondering if I can find someone to embroider it on my robes. Maybe Dorna…” Brother Qown sighed and stretched. “That’s not all. That’s not even half.” Without waiting for a response, he continued, “We were in Mereina when it was attacked. A sophisticated attack organized by genuine witches, who wiped out almost the entire town and everyone gathered for the tournament. Thousands dead.”

Father Zajhera didn’t seem surprised. Brother Qown supposed he should have expected that. Father Zajhera knew a great many people and a great many things.

“The people responsible for the attack included a Doltari woman named Senera. She released magical smoke that choked its victims—it’s how almost everyone died. However, I also saw what she did, so she wouldn’t be overcome by the smoke herself.” Brother Qown reached out and drew a line in the air, tracing out the sigil. It glowed but didn’t do much else—although Qown assumed the air around the glyph was clean and pure. The demonstration would have been more obvious if he’d drawn the glyph near smoke.

Father Zajhera’s expression shifted fast through several emotions, including anger, before settling on unhappy concern. He stared long and hard at the rune, before sighing and leaning back in his chair.

Brother Qown had known Father Zajhera for his whole life. He knew how to read the man’s moods.

“You know what this is, don’t you?”

“It’s a sigil,” the elder priest said, then shook his head. “No, I apologize. That makes it sound like a toy one might paint on a child’s nursery for luck. What you have just drawn is a symbolic and equivalent representation of tenyé, an object’s true essence. Tell me, this woman, Senera, did she keep a small stone on her person? A necklace or jewelry? Perhaps this large? A crystal?” He held thumb and forefinger a few inches apart.

“No, nothing like—” Brother Qown paused. “No. No wait. Not jewelry, no, but she had an inkstone. A small one. She kept it tucked into her bodice, pulling it out when she cut herself. She used her blood to draw that sigil on her forehead. I thought it was ritual magic.” He frowned. “I still think so. That brush must have been made from hairs pulled from all her Yoran soldiers. Sympathetic magic would have ensured her ‘sigil’ ended up on everyone’s forehead simultaneously.”

“Yes,” Father Zajhera agreed. “Astute. Even more astute to notice the sigil itself and use it to your advantage.2 I’m proud of you.”

Brother Qown blushed. “Father, I—thank you, but that glyph is what worries me. What is its nature? Where does it come from? I put no tenyé into its creation. It should have no power, yet every time this sigil is drawn, its magical effect is the same.”

For a long time, Father Zajhera said nothing. He sipped his tea as he contemplated his response. Finally, he said, “This woman, Senera. If that is her real name.3” He nodded to Brother Qown. “The stone she used is no river rock. It is the most dangerous of all Cornerstones: the Name of All Things.”

Brother Qown felt a shiver sweep through him. The priest knew very little about the Cornerstones. Father Zajhera seldom spoke of them, but Brother Qown remembered enough to know they were eight artifacts with different and significant magical abilities.

“You once told me the Cornerstones are gods trapped in stone,” Brother Qown whispered.

Zajhera waved a hand, irritated. “I was being poetic. That description gives the stones more credit for sentience than they deserve. The Cornerstones are eight gems, tied to universal concepts. They contain godlike power, but not a divine being’s will and intelligence. Such direction must be supplied by another. Anyone who holds them in fact.” His smile turned sardonic. “Even an escaped slave from Doltar.”

“What…” Brother Qown’s throat felt dry and thick. “What does the Name of All Things do? What are its powers?”

Zajhera shrugged. “Who can say with any certainty? It provides information. Its power is subtle. Its sphere is knowledge. It seems the stone can be used to answer questions. Even perhaps questions as esoteric as, what tenyé sigil might turn the air sweet and pure?”

“Any questions?” Brother Qown felt a panicked flutter in his chest. Could its owner predict the future, research their enemies’ weaknesses? What couldn’t someone do with such answers at their fingertips?

“I cannot say.” Father Zajhera set his tea aside. “But it is a mystery you must unravel.”

“But I—”

Zajhera raised two fingers. “She needs you, my son.4 She needs someone to light her path, for the dark is all around her. Xaltorath has been a terrible influence, and you have seen what she becomes when she loses control.”

“She should be trained. I have never known anyone with so much potential. Three spell-gifts, Father! She maintains her strength at all times and doesn’t even realize she’s doing it.”

“Trained by whom?” Father Zajhera said. “She’s a woman. The empire does not grant women licenses to use or learn magic. A woman who knows even a single spell-gift, no matter how much potential she may have, is a witch. And witchcraft is a crime the empire punishes with death, not slavery.”

“You know Quuros laws are vile. However, I’m not even sure they’d be applied here, because of the Joratese treatment of gender. For example, Joratese law makes it clear only men may hold a noble title, yes?”

Father Zajhera’s brows drew together. “Yes.”

“No.” Qown held up a finger as emphasis. “Only stallions can hold a noble title. But the rest of the empire assumes that means men. For example: What’s the Guarem translation for the root of the word idorrá?”

“Why, male—” Father Zajhera paused. “Male, but that isn’t actually what idorrá means.”

“No, it isn’t. Idorrá is a gender-neutral concept. But because we western Quuros can’t imagine power, or leadership, tied to anything but masculinity, we assumed the word must mean man. It doesn’t.”

“But it’s just a mistranslation, then; the Joratese clearly do understand the difference between male and female.”

“Do they? They know the difference between stallions and mares. But if you tell them only a man may inherit a noble title in Quur, they’ll nod and agree that’s how they do things here too. And if you pointed out someone like Janel has inherited a title, they would still agree they do things the same way. Because they don’t understand how that’s a contradiction.”

Father Zajhera looked confused. “But she’s female…?”

“Physically,” Brother Qown agreed. “But do you remember when you first told me about her? How you said there had been all those false reports about the Count of Tolamer having a grandson? You assumed people saw her dressed up in boy’s clothes and jumped to the wrong conclusions. I don’t think they did. Because the Joratese don’t see it the way you or I would. She’s not a mare; she’s a stallion. To the Joratese, Count Janel—and note how it’s Count and not Countess—is a man to the Joratese, by all the standards we’d use in the west. Except for one thing: she’s female.”

“But she was engaged to marry that boy—”

“It’s no scandal for two stallions to marry—and notice how those labels have nothing to do with biological sex. And they have three, you’ll note.”

“Three what?”

“Three genders. Gelding is also allowed. It has nothing to do with whether you like sex or are even capable of sex. Gelding is a catch-all term for anyone who doesn’t quite fit into the stallion and mare definitions or who doesn’t want to fit into those definitions. Anyway, there’s no reason two stallions can’t work as a match. But I gather Sir Oreth decided she should be a mare and tried to force the issue. She disagreed.” He paused. “Violently.”

“Huh.” Father Zajhera shook his head. “Well, there can be no doubt it’s a strange land. But even if they think she’s a man—or stallion—they’ll still burn her as a witch.”

“They’ll burn anyone who’s from this side of the mountains as a witch. Magical aptitude or not, apparently. It’s only us lucky few from the west who’re given a pass.” Brother Qown sighed. “I should mention the prophecy…”

Father Zajhera’s eyes regarded his, bright as gemstones.

“You knew about that too,” Brother Qown said.

“It is always hard to see where prophecies will lead,” Father Zajhera agreed. “I suppose I’d have an advantage if I had that Cornerstone, the Name of All Things, for example.5 Still, I have known for a long time that Janel is wrapped up in such matters. Why else would demons single her out? Keep doing as you have, keep your head down, report back on everything, try to help Janel without putting yourself at risk. Remember a dead physicker heals no patients. As for Count Janel…” He picked up his tea again.

“Yes?”

Father Zajhera smiled. “Being cursed by a demon breaks no laws, my son, and makes no distinctions between genders. So. I say any powers she may manifest are because of a curse. And you shall say so as well. Do we understand each other?”

Brother Qown nodded. “Yes. Of course, Father. I understand perfectly.”