22: THE COST OF IDORRÁ

Jorat Dominion, Quuros Empire. Three days since the fires started in the Capital City

Janel studied Qown for a moment. “So you’ve always known.”

Qown shifted under the scrutiny, his gaze lighting upon the other people in the tavern before settling on his hands. “Known?”

“About the source of my strength.”

“I didn’t know for certain,” he admitted, squirming, “but we suspected. Trauma often sparks spell-gifts, and, well, your talent manifested immediately following a rather terrifying amount of trauma, didn’t it?”

Mare Dorna tsked and shook her head. “My poor foal.”

“Are you still in contact with this Father Zajhera?” Kihrin frowned.

Janel and Qown looked at each other.

“I suppose we could be if we wanted, but why?” Janel asked.

“Look, I realize you both like this man a lot, but something about that story bothers me, though I can’t put my finger on it.” Kihrin snapped his fingers. “Wait. I’ve got it. Qown, you never told Father Zajhera that Senera was an escaped Doltari slave.”1

Brother Qown blinked. “I … what?”

“You never told Father Zajhera she was a slave, escaped or otherwise. So why did he say she was?”

“Oh.” Qown’s brows drew together. “I never noticed that.”

“He wasn’t wrong,” Janel said slowly, “but we didn’t know that about Senera until later. Qown, are you sure that’s what he said?”

Qown winced. “I’m sure.”

“And what does that mean?” Mare Dorna asked. “Maybe he assumed. I hear that’s how most of those people end up in Quur, ain’t it?”

Kihrin shrugged and leaned back in his chair. “I don’t know. It struck me as off, but maybe Dorna’s right and he just assumed she must have been a slave.”

“No.” Qown shut his eyes for a second. “No, he made a mistake—or he was testing me. Either way, I should have noticed.”

Janel looked at Qown oddly. “What are you talking about?”

“We haven’t reached that part of the story yet,” Brother Qown said, “but it’s your turn.”

Janel’s Turn. Barsine apartment, Atrine, Jorat, Quur.

I have wondered if it would be better if I couldn’t remember what occurred that night. Would it be cleaner, happier, if I had woken the next morning, unsure what I had done, innocent through ignorance? Could I pretend I had committed no wrong, or would I wallow in doubt? Which would be worse, to wake hoping I hadn’t killed someone or to know with absolute conviction I had?

No matter. I knew. I remembered.

I threw off the bedcovers and reached for a robe.

“Ah, foal!” Dorna scolded as soon as I moved. “You shouldn’t be out of bed.” Dorna sat at a small table by the hearth, darning the tears in my bloody tunic. She’d be the first to admit she’s a terrible cook, but amazing with needle and thread; by the time she finished, I wouldn’t be able to tell the fabric had ever been ripped. She’d dye the whole thing a new color to hide the stains.

“I’m fine, Dorna.” Which was true. I wasn’t in any pain, and touching my lower back, I felt no injury.

I picked up the bodice from the table next to her. “Who healed me? Qown?” I poked my finger through the hole in the back. The bodice could be salvaged. Not so long ago, I’d have thrown the garment out and ordered a servant to make me a replacement.

Now I would have to make do.

Dorna hadn’t answered. When I looked at her, she focused so hard on her embroidery I wondered just what had happened to me while unconscious. “Dorna? Did Qown heal my wounds?”

Dorna ignored the question as she laid her embroidery to the side. “Was it a bad one? To be fair, last time you weren’t shot through the middle, but still…”

I set the bodice back down on the table. “Where are we? Is this the Barsine apartment?”

“Aye, foal,” she said, smiling. “We’re even here legally. Kalazan granted us permission.”

“I know. Did you meet up with Arasgon and Talaras?”

Dorna gave me a hard look, started to say something, then pressed her lips together. “Foal—”

“What about my mother’s jewelry? Did you sell it?”

Dorna sighed. “No. Aroth’s always been a crafty bastard. He’s got the pawnshops watched too. But I’m wise to his tricks.” She saw the look on my face. “We’ll figure something out. I still have a little metal saved up. We’re not turning out our pockets yet. And the firebloods are fine. Romping over on the Green and catching up with old friends. Flirting with the mares like the shameless stallions they are.” The old woman stood. “Ninavis told me what happened. Don’t be hard on yourself. They were bad men.”

“They were desperate men,” I corrected. “I know nothing else about their character.”2

“They would have killed you.”

“I don’t know that. Neither do you. Unless I meet their souls the next time I’m in the Afterlife, their true intentions remain unknown to me.” I rubbed my fingertips together. Dorna or someone—Qown, maybe—must have washed my hands while I slept. They hadn’t done a very good job, though; a sticky crust of blood lingered under my nails.

“All I know for certain is I massacred them.”3

Dorna had nothing to say to that, either because she agreed or because she thought arguing with me was pointless. “Let me fetch you some breakfast.”

“No. Let’s go back to the original question. Did … Qown … heal … my … wounds?” I asked. Dorna’s refusal to answer had turned an idle question into an important one.

“Oh. I imagine he did, with Zajhera’s help—”

Zajhera? My eyes widened.

“You should rest!” she called after me as I walked out into the main room.

Most apartments in Atrine have a sameness to them. There isn’t much variety to the floor plans, although since a baron is lower ranked than a count, the Barsine apartment is smaller in scale than the Tolamer apartment. Same fireplace in the same position, same ornamental corbels, same carved ceiling, same main hall. A hundred generations had burnished the plaster walls into a soft smoothness you’d be forgiven for mistaking for marble.

A pot cooking on the hearth smelled like something spicier than normal for Joratese breakfast porridge. A large and prominent altar to the Eight held pride of place in the main hall, but only a few paintings or tapestries decorated the apartment. No sculptures, no books. That fit what I remembered of Tamin’s father, a grim man who had associated everything from art to poetry as a potential entry point for demonic corruption.

Sir Baramon, Brother Qown, and Ninavis all sat in the main hall, talking to a fourth person. He was leaning toward them in earnest enthusiasm, ignoring the spiced porridge cooling on the table beside his elbow. A white beard and plaited cloud-curl hair marked the newcomer, vivid against his Quuros brown skin. He had wise eyes and a cheerful smile.

Without him, I would never have made it to adulthood at all. Father Zajhera had saved me in a thousand ways. He’d made it possible for me to ignore the screaming in my mind, to believe I could be better than Xaltorath’s daughter.

“Have you seen her when she’s like this? It’s terrifying—” Ninavis shut up as soon as Sir Baramon nudged her with his boot. An awkward silence fell over the group as they realized I’d entered.

All except for one.

“My dearest Janel!” The old Vishai priest rose to his feet and walked toward me with arms outstretched. “My dear child, it has been too long. I’m so sorry to hear about your grandfather. His light shone to the furthest reaches of our souls.”

“Father Zajhera,” I said, trying with everything in me to keep my voice level. I had to fight the urge to run into his arms, to collapse crying with my head against his chest. Instead, I set my hand against the back of his neck, rested my forehead against his. He returned the greeting. He probably hadn’t been subject to a proper Jorat greeting since the last time he’d seen me, years before. “I thought you were across the Dragonspires.”

Brother Qown rose to his feet. “Oh, he was, Count. I sent a message for him.” He paused, and a shadow crossed over his face. “I thought it would be best.”

I stepped away from the Vishai faith’s leader, lowered my hands. “I see. Thank you, Brother Qown.” I examined them, and my heart broke. Brother Qown looked anxious, Sir Baramon shame-faced, but Ninavis—

Ninavis wouldn’t look at me at all.4

“I need the room,” I said. “Father Zajhera and I have matters to discuss.”

Silence lingered, and then everyone shuffled out.

“Ninavis?”

She paused at the doorway, turned to face me.

“I’ll speak with you when we’re done here.”

Ninavis started to say something, frowned, and nodded an affirmative before following the others.

I stared after her a moment before turning my attention back to Father Zajhera. “Your Luminance, you know I owe you everything, but you shouldn’t have come.”

The old man smiled. “Sit with me. Tell me how things have been.”

“Why? Am I to believe Brother Qown hasn’t already given you a full report?”

He tsked under his breath and patted the chair cushion across from him. “Don’t be so hard on him, child. Brother Qown called me in because he found out what I’ve known for some time: you’re not an easy person to heal. You fight it. You fight it the way a sorcerer fights a rival’s curse.”5 His kind gaze turned stern. “Now sit.”

Some ancient tone all parents learn from their children had me following his orders—I sat down by the fire across from him. “How much did he tell you?”

“Something about an evil sorcerer, an evil witch, you needing to find a way to see the duke. Continuing troubles with the Malkoessian family that have never gone away.” He leaned forward. “Nothing you can’t solve, my dear. I have all possible faith in you.”

I breathed deeply and once more fought the desire to collapse into his arms, a little girl finding comfort in the priest who had always been there for me. At least, the priest who had been there for me since I was eight years old.

Instead, I said, “I murdered six people last night. Did Brother Qown tell you?”

“Murder,” Father Zajhera answered, “requires premeditation. And if I understand the legalities, you had every right to defend yourself against those men or indeed to take their lives for their affront.” He held up a finger as I started to retort. “They didn’t belong to your herd. They were not saelen. These were dangerous men committing illegal acts. But that’s not the real problem, is it?”

I sighed and stared down at my black fingers. “No, the real issue is that I lost control.”

“So it would seem. Was it possession? Did Xaltorath return?”

“No, I…” I turned away and stared at the dancing flames. “I became so angry. Furious. It just welled up inside me like a fire I could only quench with blood. I fear … I fear I’m becoming the very thing I hate.”

“Hmm.”

I glanced back at him, blinking. “Hmm? That’s all you have to say? Hmm?”

He shrugged, leaned back in his chair, and began to eat his porridge. “This is delicious. Dorna’s cooking?”

“You said it’s delicious, so no.”

“You’re blessed to have her by your side, my child. It’s not rice, is it?”

“I haven’t the faintest. Barley? You’re changing the subject.”

He chuckled and ate more while I waited. Finally, after I dearly wanted to shout at him, he set the bowl down on a side table. “I think the young are so … dramatic.”

“Dramatic?” I stared. “I killed—”

“Yes, yes. You’re a young woman in a difficult situation, forced into making difficult choices, with extraordinary pressure on your shoulders, and an even more extraordinary weapon at your disposal—yourself. Is a demon necessary to explain why you might have lost control? Even if your perceived experience is older than your age, your body is still transitioning from child to adult. It’s not a mystery as to why you might be having a hard time.” He folded his hands over his lap. “I’m much more concerned about this business with the Baron of Barsine. What were you thinking?”

I gaped. That hadn’t even been on the list of things I had expected him to scold me over.

“I have no idea what you mean.”

The old priest sighed. “These aren’t my people, but I know enough about Joratese ways to understand the ramifications.”

I narrowed my eyes. “The ramifications? I stopped a Hellmarch, Father Zajhera. Remember how the last one went, when I was a child? They were creating a demon prince from the souls sacrificed to Kasmodeus. They were going to open up Jorat like a rotted plum.”

“Yes, and you Censured the baron, installed your own man as the new ruler—”

“I didn’t Censure anyone, and Kalazan isn’t my man—”

Father Zajhera waved a hand. “I know how idorrá and thudajé work, my dear. Kalazan is your man. You rule Tolamer—”

“Oreth would disagree.”

“Until Sir Oreth finds a way to strip your title, you’re the Count of Tolamer. And what happens, my sweet girl, when you walk into the duke’s palace, explain the danger to him, and he … dismisses the threat?”

“He won’t do that,” I protested.

“Oh, but he will. Because barring the last Hellmarch, Jorat has known peace for almost a hundred years. Your young Duke Xun cannot even begin to imagine how quickly that can change. He’ll think you’re trying to live up to your sobriquet, Janel Danorak, riding out to warn the dominion. He’ll decide you’re overwrought, upset about your grandfather’s death, looking for an angle in your feud against Oreth Malkoessian. He’ll dismiss your concerns as nothing but a young girl who thinks she’s a stallion, when she should have accepted her place as a mare. And what will you do then?”

I froze in horror as his words sank into my soul. No. No, that couldn’t be …

I shuddered. “I need to stop Relos Var. I must stop Relos Var! The town at Tiga Pass is gone, Father. Coldwater is gone. How many more towns will vanish as Mereina has? How many more will die?”6

He leaned forward, elbows resting on his knees. “And have you given any thought to what it will mean when you are the one saving these towns, banners, and cantons? When you save them, even as their rulers dismiss the threat? How will Duke Xun react when his people owe you more thudajé than they owe him?”

The blood fled from my face as I finally understood his meaning. In my eagerness to do the right thing, to stop these demons and these madmen, I had forgotten the most fundamental rule in Joratese politics.

What you protect is what you rule.

“I would—” I swallowed. “I would do it in the duke’s name. He’d take credit for any defense I offered.”

He nodded. “A commendable plan, assuming Duke Xun is smart enough to recognize your loyalty. We shall see, won’t we?” He extended his arm around me. “I have always known how special you are, Janel. Once, you led an army across Jorat—”

I made a noise, half protest, half whimper. “No, I didn’t. Xaltorath—”

“She didn’t pick you by chance.7 Oreth’s mistake—the same mistake his father, Aroth, is making, the same mistake Duke Xun will make—is to see you as inferior, someone over whom they hold idorrá. Bride, vassal, supplicant, submissive. And it’s not true. Mark my words, my daughter—before this is done, you will lead an army across Jorat again. Your idorrá will cover this whole empire, and Quur will bow before you.”

His words struck me like blows. I stared at him, mouth dry and throat tight. “I have always valued your counsel. You helped me when no one else could. But this … you’re wrong, Father. You’re wrong.” I paused to collect myself. “This is a test, isn’t it? Like the games you used to play with me to make sure I’d escaped Xaltorath’s corruption. You’re trying to ensure I’m not losing myself to pride and ambition.”

He smiled. “You see through me so easily.”

“I know I’m willful,” I said, “but I’m not thorra. I know my place. When it comes time for me to submit to Duke Xun’s idorrá, I will.”

Father Zajhera clasped me on the shoulder. As he started to speak, however, steps echoed on the stairs, quick and loud. Ninavis burst into the main room.

“Janel! You said that witch back in Mereina was a white-skinned Doltari, right?” She didn’t look panicked, but her urgency proved impossible to ignore.

“Yes. Why, what’s happened?”

“Well, I hate to interrupt you, but she’s here.”8

Because Emperor Kandor built Atrine to be a slaughterhouse rather than a capital, towers sat on many rooftops. Towers where one might sit and watch several twisting, winding streets at once, better to raise the alarm and organize a defense. Sir Baramon had been sitting in one when he saw a snow-white woman9 leading armed soldiers toward us, and sent Ninavis to find me.

“I’m not wrong, am I?” Sir Baramon squinted his eyes to make out the figures. The soldiers had stopped in a cul-de-sac, arguing over the right direction to go.

“No,” I said. “You’re not wrong. That’s Senera.” I recognized her even at this distance; the way she stood, the way she tilted her hips, had left as indelible an impression on me as her skin color. I felt dread shiver through me. She’d wiped out an entire town using magic.

Now she’d arrived in Atrine. And was on her way to the Barsine apartment.

It took no great genius to realize why this was. Only someone who knew Baron Tamin was dead or Censured would think to lodge in his empty apartments. Someone who had survived the attack on Mereina. So either Senera had the same idea we did and looked for a place to sequester herself and her men …

… or she was looking for us.10

“There.” Ninavis tugged on my arm. “The skyways.” She pointed across the roofs. I saw more men crossing over, heading toward us.

Maybe it was coincidence. More people in Atrine traveled by the skyways than traveled by the labyrinthine streets, after all.

But I couldn’t help but notice such travel cut off our escape routes. And these men roaming the skyways carried themselves like soldiers.

“They’re here for us,” I murmured. “They must be. Quickly, gather our things.”

“Perhaps I can help?” Father Zajhera suggested.

Sir Baramon frowned at him. “I’m not sure what you could do, priest, although it’s a nice offer…”

Father Zajhera took no offense at the dismissal. Indeed, his eyes twinkled with warm amusement. “Where would you like to go? Still in Atrine, I assume?”

I blinked at him, but Brother Qown stammered. “Father! This is Jorat. Are you sure such a display is wise?”

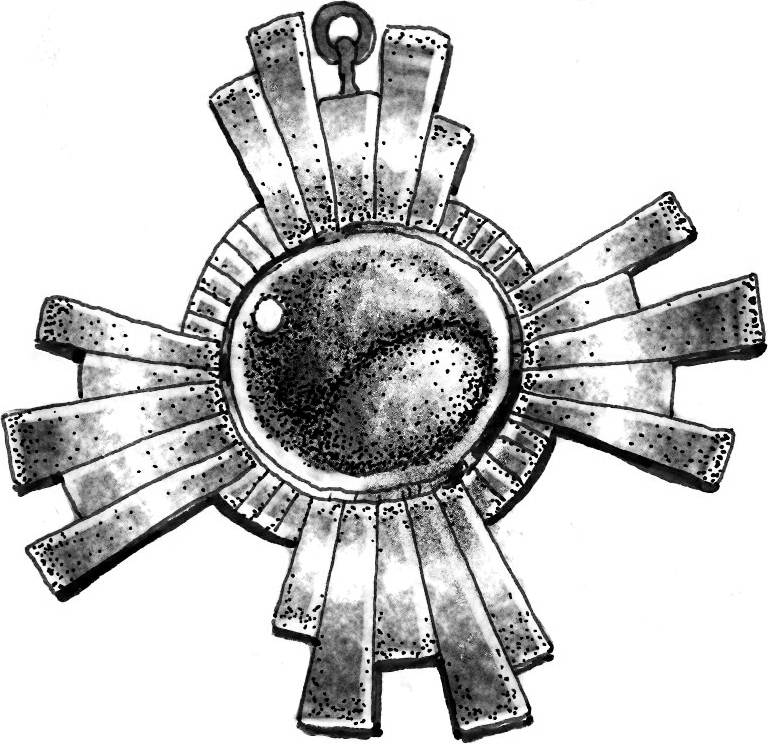

“Don’t fret. No one’s going to come after me for being a witch. That silly god-king tale about Joras and his descendants must have some advantages. Although don’t tell House D’Aramarin. I’ve never paid a lick of dues to them.”11 Father Zajhera adjusted his agolé and raised his hands, positioning his fingers just so—his body posed like a dancer before a performance. He whispered something, low and gentle and velvety, a voice to drift a thousand restless babies into slumber’s arms. Energy strands floated from his fingertips, fractal shapes coalescing in the air into mathematical skeins. There was an order to it, a pattern. It tugged at me, daring me to comprehend its meaning. The energy circle brightened, then cooled, leaving a mirror finish at its center.

A mirror finish that didn’t reflect the rooftops behind us.

“Witchcraft,” Sir Baramon sputtered.

“Blood of Joras, you oaf. He can’t be a witch. Not by anyone’s definition.” Mare Dorna crested the steps with several bags slung over her shoulders. “Now grab our things and go. There’s a saying about gifts and horses that applies right about now, so quit your whining.”

Sir Baramon started to protest.

“Follow me,” I ordered him, and I ducked back inside. I didn’t need Sir Baramon’s Joratese sensibilities about magic clashing with our need for an escape route. I hefted my travel valise and let him grab his own bags, reflecting I should be glad I’d habitually kept my possessions packed and ready to go since Tolamer. I had no idea what trinkets from the Barsine apartments had slipped and fallen into Dorna’s pockets, but I would send my apologies and replacements to Kalazan at the first available opportunity.

Back on the roof, traveling supplies now in hand, I saw the soldiers lurked just a few rooftops away. Close enough to see their faces, pale and almost certainly Yoran under makeup and disguises.

Banging echoed from the door downstairs.

“Go!” I shouted. I saluted the soldiers, then walked through the gate myself.