WHEN 14-YEAR-OLD Filipina Maria Rosa approached her school in Pasay, near Manila, on December 8, 1941, she noticed something unusual: the students were standing outside instead of going in. Why? The school was closed. Japan had attacked the Philippines.

Maria Rosa and her mother fled with some neighbors to a small village farther north on Luzon, the main island of the Philippines. Life had always been difficult for Maria Rosa, the unacknowledged daughter of a rich, already married father and the single young woman he had pressured into becoming his mistress. Maria Rosa and her mother had always lived near poverty, but now, during the Japanese occupation, survival became even more difficult.

After returning to Pasay, Maria Rosa heard there was firewood available at nearby Fort McKinley, a former US military base now being used by the Japanese. One day, after a week of collecting the bundles of firewood, on her way back from Fort McKinley, Maria Rosa suddenly came face-to-face with two Japanese soldiers. They grabbed her arms. She cried out. While she struggled to get free, a Japanese officer approached them. He yelled something in Japanese at the soldiers. Then he slapped them. Maria Rosa was relieved: she thought he was going to rescue her.

Self-portrait of Maria Rosa as a schoolgirl in 1941. Comfort Woman: A Filipina’s Story of Prostitution and Slavery Under the Japanese Military by Maria Rosa Henson (Rowman & Littlefield, 1999)

Instead, he raped her. Then he allowed the two soldiers to rape her as well, before walking away. Maria Rosa’s skirt was covered with blood. She was in so much pain, she couldn’t get up. A kind farmer who happened to pass by carried her home to his wife. She gave Maria Rosa a different set of clothes and cared for her until she felt well enough to walk home.

When Maria Rosa’s mother heard what had happened, she tried to prevent her from returning to the fort. But because they needed the wood, Maria Rosa returned without her mother’s permission, this time accompanied by her uncles and neighbors. Certainly, she thought, being in a large group would offer her protection.

It didn’t. When they all arrived at the fort, Maria Rosa saw the officer who had raped her. He recognized her, and in full view of her uncles, who were helpless to intervene, he raped her again.

Maria Rosa’s horrified mother was determined to leave the area. They moved to her home village of Pampang (in the Pampanga province), where they shared a house with a male relative by the name of Pinatubo. He was a commander in the Hukbalahap, a Communist-based Filipino guerrilla army referred to as the Huk.

One day Pinatubo asked Maria Rosa if she wanted to join the Huk. She was glad to be offered a chance to fight back against the Japanese. After joining, she was assigned to carry messages and collect food, medicine, and clothing from people sympathetic to the Huk guerrillas.

Once, while on her way to collect medicine and deliver a message, Maria Rosa saw some Japanese soldiers a long way off. She quickly ate the message. The soldiers suspected nothing and let her pass.

But Maria Rosa knew she’d had a close call. Those suspected of working with the Huk were always taken to the local Japanese garrison, where they were tortured for information before being killed. So the Huk held their meetings in different neighborhoods in order to avoid detection. And as Maria Rosa went from village to village for the Huk, she was careful to never disclose her real identity: her code name was Bayang.

Maria Rosa’s work gave her a deep sense of purpose. Yet she was continually haunted by the memory of the rapes, especially when she sang the following lines of a song with her comrades:

They should be vanquished, the fascist Japanese,

The scourge of our race.

They seized our possessions and raped our women.

After singing those words, Maria Rosa would always whisper to herself, “I am one of those women.”

One morning in April, 1943, Maria Rosa and two male comrades, riding in a cart pulled by a carabao (a type of water buffalo), approached a Japanese checkpoint. The cart looked like it was filled with sacks of corn, but some of the sacks also contained ammunition and weapons.

Maria Rosa showed the Japanese sentry their passes. He touched some of the corn sacks. Then he allowed them to move on.

But before they got far from the checkpoint, the sentry whistled and signaled for them to return. “We looked at each other and turned pale,” Maria Rosa wrote later. “If he emptied the sack, he would surely find the guns and kill us instantly.”

A Hukbalahap meeting. Sketch by Maria Rosa Henson. Comfort Woman: A Filipina’s Story of Prostitution and Slavery Under the Japanese Military by Maria Rosa Henson (Rowman & Littlefield, 1999)

Then the sentry pointed to her: she was the only one who needed to return.

“I walked to the checkpoint, thinking the guns were safe but I would be in danger. I thought that maybe they would rape me.”

At gunpoint, the sentry led Maria Rosa to the second floor of a Japanese garrison. There she saw six other women. She was led a small room with a bamboo bed and no door, only a curtain.

On the following day, one that she would later describe as “hell,” Maria Rosa discovered why she and the other women had been brought to the garrison. A Japanese soldier entered her room. He pointed a bayonet at her chest. She was terrified; she thought he was going to kill her. Instead, he slashed her dress open. Then he raped her.

Most of the approximately 200,000 so-called comfort women who were enslaved in “comfort stations” (in reality rape stations) by the Japanese military throughout Asia during World War II were lured by false promises of regular work. But in the Philippines, because the Philippine resistance movement was so strong and Japanese troops stationed there regarded most civilians as being possible resisters, the Japanese usually abducted women and girls openly. By early 1943 in Manila alone there were 17 rape stations for soldiers, “staffed” by 1,064 enslaved women, and four officers’ clubs served by 120.

Twelve more soldiers followed.

When it was over, Maria Rosa was in extreme pain and bleeding profusely. Another woman brought some food in the morning, but Maria Rosa wasn’t allowed to talk to her. There was a guard by the door to prevent not only escape but conversation as well; the Japanese had isolated these women, in part, to prevent them from engaging in any espionage while in contact with the Japanese military men.

From then on, Maria was raped repeatedly every day and often beaten during the process. “At the end of each day,” she wrote later, “I just closed my eyes and cried.” She couldn’t see any way out. She knew that an escape attempt would mean death. Only love for her mother kept her from suicide.

At one point the women were transferred from the garrison to a rice mill that a new set of officers had taken over. One of them was the officer who had raped Maria Rosa outside of Fort McKinley the year before. His name was Captain Tanka. He recognized Maria Rosa and took pity on her several times when she became ill with malaria, allowing her to recover in his own room, usually without raping her. She was beginning to learn some Japanese, and Tanka had learned some English. One day she pleaded with him to help her escape. He refused, saying that doing so would break his vow to serve the emperor. And “he could do nothing against the Emperor.”

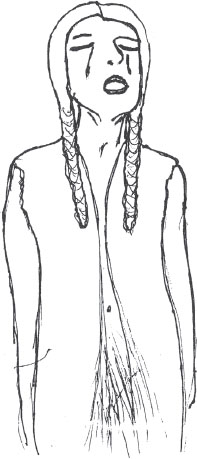

Maria Rosa Henson self-portrait. “I cried every night, calling my mother silently.” Comfort Woman: A Filipina’s Story of Prostitution and Slavery Under the Japanese Military by Maria Rosa Henson (Rowman & Littlefield, 1999)

One day, Tanka asked Maria Rosa to bring tea to his room. When she entered, she found him in conversation with a Japanese colonel. They were discussing plans to burn Pampang to the ground in retaliation for suspected guerrilla activities there. Maria Rosa knew that when the Japanese burned a village, they also set up their machine guns around the outside so they could fire on anyone who managed to escape the flames. Her village was doomed!

She was determined to alert Pampang. She found her opportunity on the following day. When the guards let the women out for some sunshine, Maria Rosa went as close to the street as the barbed wire would allow. She saw an old Filipino man walk by. She knew he lived in Pampang. The guards were distracted, laughing and talking together. They didn’t see her whisper a warning to the old man.

That evening she saw Captain Tanka and the colonel leave with some soldiers. When they returned one hour later, the two officers rushed up the stairs to her room. The colonel slapped her viciously. Why? They had found Pampang deserted. Maria Rosa was the only civilian who could have possibly overheard their plans.

She was dragged to the basement, beaten, and tied up. When she dared to open her eyes and look around, she recognized some Huk guerrillas, also bound with rope, their bodies and faces covered with bruises.

Captain Tanka came down and tried to give Maria Rosa some tea. But the colonel stopped him. Then he banged Maria Rosa’s head against the iron wall. She lost consciousness.

That night, Huk guerrillas attacked the garrison in order to save their comrades. They also rescued the unconscious Maria Rosa. She was eventually taken to her mother’s house.

When she regained consciousness, she couldn’t walk or even sit up. She couldn’t speak. Her mouth constantly hung open. Her vision was blurry. She tried to write down what she was experiencing but couldn’t hold the pencil. Her mother had to care for her as if she were a baby.

As she regained her ability to speak, Maria Rosa told her mother what the Japanese soldiers had done to her. Her mother wouldn’t allow her outside for almost a year for fear the Japanese soldiers would recognize her and take her back.

When they heard the news that Manila was liberated, everyone was overjoyed. But Maria couldn’t stop crying; tears not of joy but of sorrow that the Americans had come too late to save her from her ordeal. She was continuously tormented, not only by her horrific memories but because she hadn’t tried to escape.

Maria Rosa recovered enough to marry Domingo, a kind Filipino soldier who had been a guerrilla during the war. She didn’t tell him about the full extent of her ordeal, but she did admit she’d been raped by Japanese soldiers. He loved her and said that her past didn’t matter. They had three children together.

Their marriage ended when Domingo was abducted by a group of Filipino guerrillas who had been Communist Huks during the war. After the war, when General Douglas MacArthur arrested Huk leaders and ordered their followers to disband, many escaped to the mountains with their weapons. There they tried to fight against wealthy landlords who had fled to urban areas during the war and were now demanding back rent from their war-impoverished tenants, many of them former guerrilla fighters who had lost everything. Domingo stayed with these guerrillas, became their leader, and took another wife.

Now on her own, Maria Rosa went to work in a factory and used her earnings to ensure that her children and grandchildren each received an education. She didn’t tell anyone about what happened to her during the war.

Then one morning in 1992, she heard a woman on the radio discussing the topic of so-called comfort women who had been forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese government during the war.

Maria Rosa began to shake uncontrollably. She heard the woman on the radio discuss something called the Task Force on Filipino Comfort Women. “Don’t be ashamed,” the woman said. “Being a sex slave is not your fault. It is the responsibility of the Japanese Imperial Army. Stand up and fight for your rights.”

“My heart was beating very fast,” Maria wrote later of that moment. “I asked myself whether I should expose my ordeal. What if my children and relatives found me dirty and repulsive?”

She didn’t call in, but she listened to that radio station every day. A few weeks later, she heard a similar announcement. She began to weep. At that moment, her daughter Rosario walked in. Maria Rosa finally told her the truth.

Rosario helped her get in touch with the task force. Maria Rosa was interviewed on tape, Rosario at her side. It was extremely difficult, but also a relief. “I felt like a heavy weight had been removed from my shoulders,” she wrote later, “as if thorns had been pulled out of my grieving heart. I felt I had recovered my long-lost strength and self-esteem.”

Maria Rosa was the first Filipina comfort woman to break her silence. The task force now asked her to take a more public stance. She couldn’t refuse. “There were others, like me,” she wrote later, “and they, like me, needed to have a measure of justice before they died. I also wanted to make the younger generation aware about the evils of war.”

She gave press conferences and made radio appearances. And later that year, she met other former Filipina comfort women. Her efforts eventually inspired a total of 168 former Filipina sex slaves to come forward.

In April 1993, with Maria Rosa in the lead, 18 former Filipina comfort women officially filed a lawsuit against the Japanese government, demanding an official apology and some money for each woman. Testifying in Japanese court was extremely strenuous for these older women who had waited so long to tell their stories.

While waiting for the court case to go through, Maria Rosa wrote her memoir. She was able to recall many details because she had “learned to remember everything, to remember always, so [she would] not go mad.” She wanted to tell her story, she said, so that the Japanese rapists would “feel humiliated.”

The Japanese government insisted it owed the women nothing since it had already paid some postwar reparations to the Philippine government. However, with increased pressure to acknowledge the former sex slaves of many Asian nations, the Japanese government allowed the creation of the Asian Women’s Fund. Maria eventually accepted a $19,000 settlement from this fund, a move that was criticized by some who thought she should have waited for direct compensation from the Japanese government.

With her settlement money, Maria Rosa bought a small house in Manila. She died there in August 1997.

Comfort Woman: A Filipina’s Story of Prostitution and Slavery Under the Japanese Military by Maria Rosa Henson (Rowman & Little-field, 1999).

Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery in the Japanese Military During World War II by Yoshimi Yoshiaki (Columbia University Press, 1995).

50 Years of Silence: Comfort Woman of Indonesia by Jan Ruff-O’Herne (Editions Tom Thompson, 1994).