Tomb 1 at Shuanggudui 雙古堆, Fuyang 阜陽, Anhui, ranks as one of the more important among the many notable discoveries in the 1970s of tombs containing texts.1 Excavated in 1977, the tomb has many parallels with the better-known Tomb 3 at Mawangdui 馬王堆, Changsha 長沙, Hunan, discovered just four years earlier.2 The two tombs are very close in date and both were tombs of local rulers, Tomb 1 at Shuanggudui being the tomb of Xia Hou Zao 夏侯竈, the second-generation Lord of Ruyin 汝陰, who died in 165 B.C. Although much less well preserved than Tomb 3 at Mawangdui, which contained the famous trove of manuscripts written for the most part on silk rolls, Tomb 1 at Shuanggudui also contained numerous manuscripts, almost all of which were written on bamboo strips.3 The manuscripts include at least portions of the following texts:

• Zhou Yi 周易, or Zhou Changes4

• Shi jing 詩經, or Classic of Poetry5

• Fragments of poetry, including Chu ci 楚辭, or Verses of Chu

• Cangjie pian 倉頡篇, or Scroll of Cangjie9

• Wan wu 萬物, or Ten Thousand Things10

• two different annals extending from the Western Zhou until the Han11

• divination materials similar to the Xingde 刑德, or Punishment and Virtue, and rishu 日書, or daybook texts known from other tombs12

• a text similar to the Chun qiu shi yu 春秋事語, or Stories and Sayings of the Spring and Autumn text from Mawangdui13

• a text for officials that the excavators refer to as Zuo wu yuan cheng 作務員程, or Per Capita Rate for Work Duties

• a text for assessing the qualities of dogs entitled Xiang gou jing 相狗經, or Classic for Physiognomizing Dogs

• a physiological text referred to as Xing qi 行氣, or Moving the Vapors

• and three wooden boards (du 牘) that seem to be the tables of contents of three separate works, the most complete among them being a text entitled Ru jia zhe yan 儒家者言, or Sayings of the Ru School, that seems to have much in common with the received text Kongzi jia yu 孔子家語, or School Sayings of Confucius, and another being that of the Chun qiu shi yu 春秋事語, or Stories and Sayings of the Spring and Autumn14

Unfortunately, only fragments of most of these texts survived their long burial and the tomb’s excavation; fortunately, for our purposes, the best-preserved manuscript is that of the Zhou Yi.

Excavation and Initial Organization Work

At the time of its excavation, Shuanggudui was located about two miles southwest of what was then downtown Fuyang, within the perimeter of the municipal airport. As the name implies, literally, “paired ancient tumuli,” the site featured two ancient tomb mounds, similar to the tumuli at Mawangdui. The entire site constituted a rise of more than 20 meters high and about 100 meters east-west by 60 to 70 meters north-south, with the two mounds protruding in the middle. During the first week of July 1977, with the airport undergoing expansion, local archaeologists from the Anhui Provincial Archaeological Relics Work Team were called on to excavate the two tombs. The mounds were each found to cover the mouth of a tomb, Tomb 1 (M1) being to the east and Tomb 2 to the west. When opened, M1 turned out to be 9.2 meters long north-south at the mouth, 7.65 meters wide east-west, with a tomb ramp 4.1 meters wide; this is just about half as large as Tomb 3 at Mawangdui. The tomb chamber, 6.2 meters long by 3.8 meters wide, was divided into several compartments, the coffin chamber being to the east. The tomb had been burgled in antiquity, causing the massive beams of the chamber’s ceiling (it is worth noting that markings on these beams, left 1, left 2, right 3, etc., show that they had been prepared off-site and assembled in situ) to collapse into the tomb chamber itself. Although many of the grave goods in the tomb must have been looted at this time, there nonetheless remained numerous lacquer vessels and implements, bronze weapons, a bronze lamp, bronze mirror and bronze cauldron, a few iron weapons, and pottery musical instruments. Perhaps the most important of the grave goods were two well-preserved diviner’s boards (shi pan 式盤), both composed of a square “earth board” (di pan 地盤) and round “heaven board” (tian pan 天盤), one depicting the twenty-eight lunar lodges and the other used for a type of divination referred to as liu ren 六壬 (the six ren days).15

Many of the artifacts in the tomb were inscribed with the name Ruyin Hou 女 (汝) 陰 侯, “Lord of Ruyin.” The first Lord of Ruyin was Xia Hou Ying 夏侯嬰 (d. 172 B.C.), a close confederate of Liu Bang’s 劉邦 (r. 202–1995 B.C.), founder of the Han dynasty. The second-generation lord was Xia Hou Zao, who ruled the state for seven years (r. 171–165 B.C.).16 Zao was followed by Xia Hou Si 夏侯賜 (164–134 B.C.), then Xia Hou Po 夏侯頗 (r. 133–115 B.C.), who was forced to commit suicide, bringing the state to an end. Since the contents of the tomb can be dated roughly to the first half of the second century B.C., and since several pieces are dated to years of reign, presumably referring to the reign of one or another of the Han emperors, the latest date notation being shiyi nian 十一年 (eleventh year), the excavators concluded that this was the tomb of Xia Hou Zao, who died in the fifteenth year of Emperor Wen 文 of Han (r. 179–157 B.C.), that is, 165 B.C.

The excavation of the Shuanggudui tombs was beset by numerous difficulties. There are conflicting reports as to whether it was planned in advance or was an emergency salvage operation; that the tumuli were well-known to be ancient tombs would presumably support the former possibility. In any event, when M1 was opened, not only was it found to have been looted in antiquity but also it was filled with groundwater.17 The collapse of the ceiling beams had caused considerable damage, in particular to the bamboo strips. The strips had originally been placed in a lacquer container in the eastern coffin chamber, but this container was destroyed and the strips damaged when the ceiling beams collapsed on top of them. The archaeologists retrieved three clumps of bamboo material, fused together by the pressure of the ceiling beams on them. Since there are no complete bamboo strips, it seems clear that the beams broke the scrolls lengthwise in one or more places. Other isolated fragments of bamboo strips were pumped out of the tomb with the groundwater that had filled it.

The bamboo strips, including especially these three clumps of bamboo material, were shipped to Beijing, where Han Ziqiang 韓自強, director of what was then called the Fuyang Local Museum (Fuyang Diqu Bowuguan 阜陽地區博物館) and the local archaeologist in charge of the excavation, and the late Yu Haoliang 于豪亮 (1917–1982), the head of the Ancient Documents Research Office of the Bureau of Cultural Relics, were assigned responsibility for “organizing” (zhengli 整理) them. Although as far as I know no measurements of these clumps have been published, Hu Pingsheng 胡平生, who joined the organization efforts after the death of Yu Haoliang in 1982, has reported to me that the largest of the three, the one containing the Zhou Yi text, was approximately 25 cm long by about 10 cm wide and 10 cm high; he described the other two clumps as being “rather smaller.” It seems apparent from the dimensions that the clumps were originally scrolls or bundles of bamboo strips, though probably not discrete bundles, since each clump contained strips of different texts.

Once in Beijing, the clumps were soaked in a weak vinegar solution to remove any mud adhering to them and then baked in an oven to remove the excess moisture. Han Ziqiang then began the effort of peeling off individual strips. Unfortunately, no record was made of where the individual pieces came from or in what order they were taken. Hu Pingsheng has described to me that the clumps were held in the hand and twisted and turned to get at whichever strip it might next be possible to pry free. There are reports that this painstaking process took the better part of two years, and that the bamboo had become so thin and so brittle that it would occasionally crumble into dust at the merest touch.18 Occasionally (though apparently not in the case of the Zhou Yi manuscript), the ink of the record would adhere to the back of the strip immediately above it and would then have to be read as a mirror image. Finally, each of the individual strips was photographed. Hu Pingsheng has told me that although every effort was made to make full-size photographs, because of different lighting needs the photographer occasionally moved the camera slightly, rendering some pieces slightly not to scale. Unfortunately again, no record was made of which pieces are not to scale. Nevertheless, Hu informs me that in no case would the discrepancy be very great.

Given all these circumstances it is miraculous that anything at all has survived. As it is, the editorial efforts of Han Ziqiang and Hu Pingsheng have produced a good, if still incomplete, idea of what the Zhou Yi manuscript looked like. Han Ziqiang has identified 752 fragments as belonging to the Zhou Yi text,19 with a total of 3,119 characters. Of these, 1,110 characters belong to the basic text (i.e., the received text of the Zhou Yi), including three different hexagram pictures (gua hua 卦畫),20 with passages from 170 or more hexagram or line statements in fifty-two different hexagrams.21 The remaining 2,009 characters belong to divination statements appended to each hexagram and line statement of the basic text.22 These divination statements, which concern such personal topics as someone who is ill (bingzhe 病者), one’s residence (ju jia 居家), marriage (qu fu 取婦 or jia nü 家女), someone who is pregnant (yunzhe 孕者), and births (chan zi 產子); administrative topics such as taking an office (lin guan 臨官 or ju guan 居官), criminals (zuiren 罪人), jailings (xi qiu 繫囚), someone who has fled (wangzhe 亡者), and military actions (gong zhan 攻戰 or zhandou 戰斵); general topics such as undertaking some business (ju shi 舉事) or trying to get something (you qiu 有求) or traveling (xing 行) and hunting and fishing (tian yu 田漁); and, of course, the weather: whether it will be fine (xing 星, i.e., qing 晴), rain (yu 雨), or if the rain will stop (qi 齊), as well as other more occasional topics, are perhaps the most interesting feature of the manuscript. Later in the chapter I discuss their general implications for the history of the Zhou Yi. Before doing so, however, it is perhaps useful to describe as carefully as possible the physical characteristics of the Fuyang Zhou Yi manuscript.23

Physical Nature of the Fuyang Zhou Yi Manuscript

We can try to go further to get some sense of the physical nature of the manuscript. Han Ziqiang reports simply that the longest fragment (he does not indicate which fragment, but it is presumably no. 126) is 15.5 cm long, 0.5 cm wide, and bears twenty-three characters.24 Hu Pingsheng has been more conclusive, saying that the strips were “possibly about 26 cm long.”25 I suspect that Hu was influenced in this conjecture by the work he had done earlier with the Fuyang Shi jing manuscript, the strips of which he demonstrated to be about 26 cm long, bound with only two binding straps, one at the top and one at the bottom.26 In fact, there is clear evidence that the bamboo strips of the Zhou Yi manuscript were considerably longer than this, even if there is not a single strip intact and it is still unclear exactly how long they were.

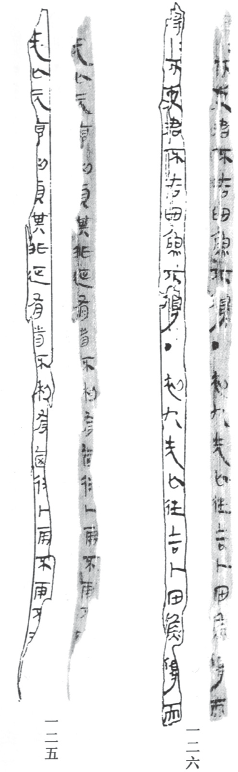

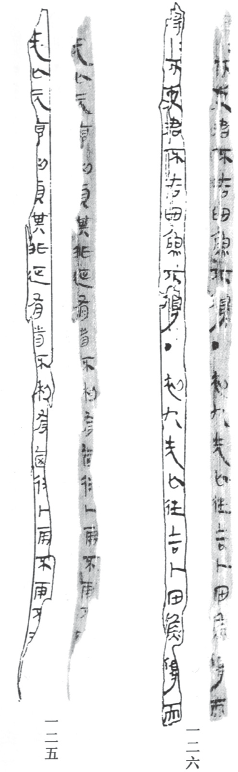

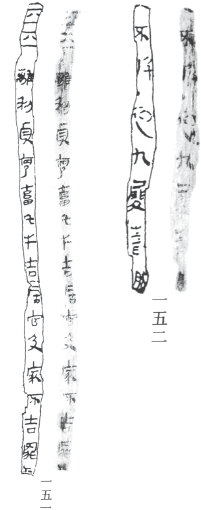

It seems clear first of all that, like the subsequently discovered Shanghai Museum manuscript, each of the sixty-four discrete hexagram texts begins on a new strip, with the text of the hexagram copied on consecutive strips until completed, with the remainder of the last strip left blank, as can be seen clearly in no. 277 and no. 354 (see figure 6.1). The hexagram text begins with the hexagram picture, with yang lines drawn as 一 and yin lines drawn more or less as ハ, coming at the very top of a strip (for evidence of this, see strips 64 and 151, and especially no. 86; figure 6.2). Under this, but separated by a space large enough to accommodate the top binding strap, comes the hexagram name, as can be seen in strip no. 86. In subsequent strips, the area above the top binding strap was left blank, as can be seen, for instance, in strip no. 141 (figure 6.3), leaving a blank area of 1.5 cm from the top of the strip to the top of the first character. A similar border was created by the bottom binding strap, also leaving an area of 1.5 cm from the bottom of the last character to the bottom of the strip, as can be seen, for example, in strip no. 140 (figure 6.4).

It is also clear that the strips of the Zhou Yi manuscript were bound with three binding straps, including one at the middle as well as those at the top and bottom. Evidence of this can be seen, for instance, on strip no. 58 (figure 6.5), on which a gap between the tenth and eleventh characters, zhe 者 and bu 不, was left to accommodate such a middle binding strap. I give the text according to the transcription of Han Ziqiang, labeled according to his entry numbers.27

58. 戰斵遆强不得志卜病者 不死乃 • 九四乘高唐弗克

58. … battling: the enemy will be strong but will not obtain its will; divining about someone who is sick: if they do not die then they will get better. • Nine in the Fourth: Riding on a high platform, you cannot …

By estimating the distance between the top and middle or middle and bottom binding straps, it should be possible to come to some idea as to the length of the original strip. Unfortunately, both the top and bottom of strip no. 58 have been broken. However, strip no. 58 can almost certainly be rejoined with strip no. 57.

57. 興卜有罪者兇

57. … arise. Divining about a guilty one: ominous …

Strip no. 57 contains the last character of the Nine in the Third line statement of Tong Ren 同人, “Fellow Men,” hexagram,28 and no. 58 contains the beginning of the Nine in the Fourth line of the same hexagram, that is, the line immediately following it in the received text of the Zhou Yi. Strip no. 57 is clearly the top of a strip (see figure 6.6), with the top 1 cm of the strip blank. As mentioned, evidence from other strips indicates that the blank area at the top of strips was 1.5 cm long, and indeed it is clear from the photograph that the tip of this strip has broken off, presumably losing about 0.5 cm. At the bottom of this fragment, only the very top portion of the character xiong 兇, “ominous,” is extant, the strip having been broken in the middle of the character. Strip no. 57 is 5.1 cm long. Strip no. 58 is 19 cm long in all, though, as I said, it is broken at both ends. The top of this fragment breaks right in the middle of the character zhan 戰, “battling.” Combining the two strips gives the following text:

57. 興卜有罪者兇

58. 戰斵遆强不得志卜病者 不死乃 • 九四乘高唐弗克

• 九四乘高唐弗克

57. … … arise. Divining about a guilty one: ominous …

58. … battling: the enemy will be strong but will not obtain its will; divining about someone who is sick: if they do not die then they will get better. • Nine in the Fourth: Riding on a high platform, you cannot …

From the top of no. 58 to the space left for the middle binding strap is 9.5 cm. Adding this to the 5.1 cm of no. 57 (actually, at least 5.5. cm, allowing for the breakage at the top of the strip), would suggest that the original strip was at least 30 cm long (9.5 + 5.5 = 15 x 2 = 30). However, it is also clear that the two fragments cannot be rejoined neatly. Not only have the characters xiong 兇 and zhan 戰, the last and first characters of the two fragments, been broken off in the middle, but also it would seem from the phrasing of the divination statements that at least the one character bu 卜, “divining,” must have come at the head of the phrase zhan dou di qiang bu de qi zhi 戰斵遆强不得志, “battling: the enemy will be strong but will not obtain its will.” By comparison with the characters zhi bu bing 志卜病, “will; divining about sick,” farther down on fragment no. 58, the length of this fragment would have been at least 1.5 cm. This would make the entire strip at least 33 cm long and possibly longer if there were other intervening text.

A second case is fragments 125 and 126 (figure 6.7):

125. 无亡元亨利貞其匪 有眚不利有攸往卜雨不雨不

有眚不利有攸往卜雨不雨不

126. 齊 不吏君不吉田魚不得 • 初九无亡往吉卜田魚得而

不吏君不吉田魚不得 • 初九无亡往吉卜田魚得而

125. Nothing Gone: Prime receipt; beneficial to determine; his not going to correct has curses; not beneficial to have someplace to go. Divining about rain: it will not rain; it will not …

126. … about clearing: it will clear; about not serving the lord: not auspicious; about hunting and fishing: you will not obtain anything. • First Nine: Nothing Gone goes; auspicious. Divining about hunting and fishing: you will obtain something and …

Fragment 125, which is 15.5 cm long, begins with the Wu Wang 无亡, “Nothing Gone,” hexagram name, followed by its hexagram statement. Comparison with other hexagram texts shows that this hexagram name would have come immediately below the top binding strap, above which would have been the hexagram picture, unfortunately broken off here. As already pointed out, these heads of strips were 1.5 cm long. The bottom of the strip is also broken. Fragment 126, which is also 15.5 cm long, begins with divination statements before continuing with the Nine in the First line statement of Wu Wang hexagram, that is, the line statement immediately following the hexagram statement on no. 125. It seems certain that these two strips can be rejoined, the only questions being whether there were any intervening fragments between them and whether the blank space visible after the “•” symbol indicating the division between line statements was intentionally left to accommodate a middle binding strap. The answer to the second question is probably negative. Although there is a distinct space after the “•” symbol, it is not as pronounced as the spaces that were surely meant to accommodate a binding strap (such as on fragment 58). Moreover, if this were the place where the middle binding strap passed, and if fragments 125 and 126 were originally a single strip, as seems clearly to be the case, then that binding strap would have been placed at least 24.5 cm from the top of the strip, suggesting that the entire strip was almost 50 cm long; there is no other evidence that the Fuyang strips were so long. However, with respect to the first question, whether any other fragment or fragments might have intervened between no. 125 and no. 126, the answer would probably have to be “probably.” The divination statement that ends no. 125 concerns whether it will rain (bu yu 卜雨, “divining about whether it will rain”), with the predicted result being that it will not (bu yu 不雨, “it will not rain”),29 followed by the upper left-hand portion of the character bu 不, “not,” and the upper left-hand portion of two horizontal lines. Fragment 126 begins with what the editors transcribe as qi 齊, “to clear,” though the photograph fails to register any character at all here and even the hand copy is incomplete. Whether or not this character should in fact be transcribed as qi (and it is not at all certain that it should be; the character qi certainly occurs on fragment 631, where the bottom right-hand portion—all that survives of the character on no. 126—is rather different from what is seen here), it seems unlikely that the two horizontal lines at the bottom of no. 125 are part of this character. It seems likely that there was at least the bottom portion of this one character here on no. 125, perhaps followed by a space. As for the character on no. 126 transcribed as qi, it is followed by a repetition mark ( ), indicating that the character is to be read twice, presumably the first time as the topic of the divination and the second time as the predicted result, that is, “[divining about] whether it will not .. clear; it will clear.” Since the divination topic concerning rain that comes at the end of no. 125 and this one about it “clearing” are clearly related, it seems likely that no. 126 would have immediately followed no. 125. The most likely scenario for these two fragments is that they were broken at or about the top and bottom binding straps and also at the middle binding strap. This is consistent with what is seen elsewhere with bamboo-strip manuscripts. The bamboo strips were routinely notched at the points where the binding straps passed in order to keep the silk or hemp strap from sliding up and down the strip. Unfortunately, these notches tended to weaken the strips at these points, often causing them to break. If this is the case here, then the middle binding strap would have come at about 17 cm or 17.5 cm from the top of the strip, suggesting a total length for the strip of 34 cm or 35 cm, fairly close to the result obtained from the analysis of fragments 57 and 58.

), indicating that the character is to be read twice, presumably the first time as the topic of the divination and the second time as the predicted result, that is, “[divining about] whether it will not .. clear; it will clear.” Since the divination topic concerning rain that comes at the end of no. 125 and this one about it “clearing” are clearly related, it seems likely that no. 126 would have immediately followed no. 125. The most likely scenario for these two fragments is that they were broken at or about the top and bottom binding straps and also at the middle binding strap. This is consistent with what is seen elsewhere with bamboo-strip manuscripts. The bamboo strips were routinely notched at the points where the binding straps passed in order to keep the silk or hemp strap from sliding up and down the strip. Unfortunately, these notches tended to weaken the strips at these points, often causing them to break. If this is the case here, then the middle binding strap would have come at about 17 cm or 17.5 cm from the top of the strip, suggesting a total length for the strip of 34 cm or 35 cm, fairly close to the result obtained from the analysis of fragments 57 and 58.

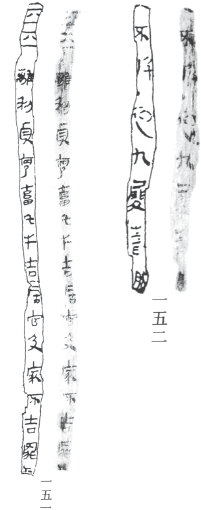

There are other cases that suggest that the strips were slightly longer. Fragments 151 and 152 contain the opening of Li 離, “Fastening,” hexagram and can probably be directly rejoined (see figure 6.8).30

151.  離利貞亨畜牝牛吉居官及家不吉罪人

離利貞亨畜牝牛吉居官及家不吉罪人

152. 不解 • 初九履昔然

151.  Fastening: Beneficial to determine; receipt. Rearing a female bovine: auspicious. Residing in office and the family: not auspicious; about a guilty man: …

Fastening: Beneficial to determine; receipt. Rearing a female bovine: auspicious. Residing in office and the family: not auspicious; about a guilty man: …

152. … he will not be released. • First Nine: Stepping crosswise;

The last character of fragment 151 seems to be the top portion of ren 人, “man,” consistent with the wording of other fragmentary divination statements (as, for instance, no. 421 and no. 422), and this is how the editors have transcribed it. At the very top of fragment 152, one can just barely make out what might be the lower right-hand portion of the character ren 人; if so, then the fragments should surely be rejoined. In any event, the phrase zui ren bu jie 罪人不解 understood as “[divining about] a guilty man: he will not be released” would seem to constitute a discrete divination topic and result, again suggesting that the two fragments should be rejoined. However, if they are rejoined in this way, given that no. 151 is 12.7 cm long and no. 152 is 5.7 cm long and that neither of them reveals any space for a middle binding strap (no. 151 shows clear evidence of a top binding strap), then the middle binding strap could not have come less than about 18.5 cm from the top of the strip, suggesting that the entire strip would have been at least 37 cm long.

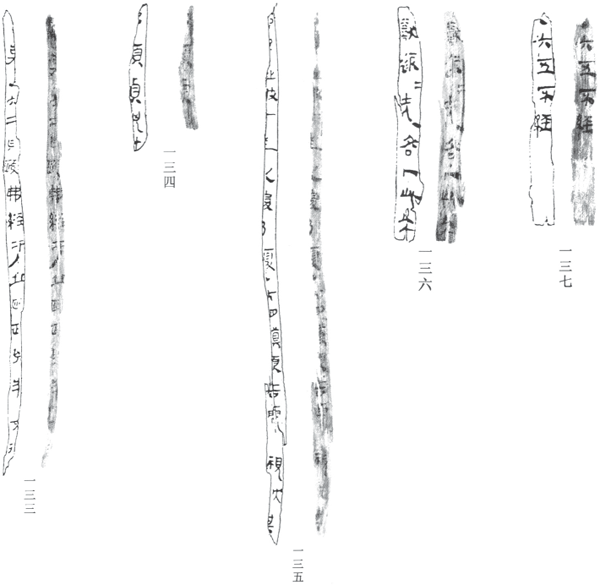

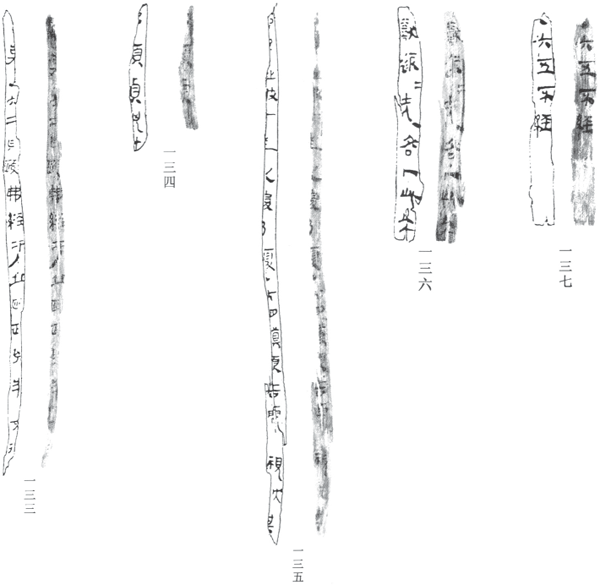

The final case to examine includes five fragments that almost certainly constituted portions of two successive bamboo strips, nos. 133–37, including text from the Six in the Second through the Six in the Fifth line statements of Yi 頤, “Jaws,” hexagram (see figure 6.9).

133. 囗吏 • 六二奠頤弗經于丘頤政凶求不得

134. 弗頤貞凶[十]

135. 囗囗囗囗十年之後乃復 • 六四顛頤吉虎視眈 其

其

136.  遂

遂 无咎卜此大

无咎卜此大

137. • 六五不經

133. … serve. Six in the Second: Placing the jaws; not passing it through the mounded jaws; governing: ominous. Seeking: one will not obtain; …

134. … not jawing it; determining: ominous. For ten …

135. .. .. .. .. after ten years then it will return. • Six in the Fourth: Overturning the jaws: auspicious. A tiger watches fearsomely, its …

136. appearance so compliant; there is no trouble. Divining about this: there will be great …

137. … • Six in the Fifth: Not vertical; …

Although there is no question that these five fragments go together in this order, there is considerable uncertainty about how they do so, and this renders the following analysis more problematic than the analyses above. Nevertheless, there is enough evidence to suggest that the analysis is worthwhile. One begins with evidence for three different binding straps: at the top of fragment 133, which could reflect either a top or, as I suggest more likely, middle binding strap; a middle binding strap on no. 135; and a bottom binding strap on no. 137. In addition to this evidence of spaces for binding straps, it is also noteworthy that the bottom of no. 133 is broken obliquely from right to left, as is the top of no. 134; this may well suggest that they were broken with the same directional force, even if it is clear that a fragment bearing at least a “•” symbol and the two characters liu san 六三 “Six in the Third,” would have come between no. 133 and no. 134. Although this would mean that the only divination statement attached to the Six in the Second line would be qiu bu de 求不得 “Seeking: one will not obtain,” there are other cases in which only a single divination statement is attached to a given line statement. If this is the case, and if no. 134 was broken at the notch for the bottom binding strap (this is a very big “if,” but not without its justification), then this bottom half of a strip would be at least 11.4 cm (no. 133) + 1.5 cm (•六三; for which, see fragment 249) + 3.0 cm (no. 134) + 1.5 cm (the foot of the strip), or 17.4 cm. That this result is more or less consistent with the results obtained above in the case of strips 151 and 152 might encourage us to accept it. Fragments nos. 135–136–137 seem almost certainly to constitute a separate single strip. Fragment no.135 is about 15.2 cm long, with space for a middle binding strap at about 12 cm; no. 136 bears text that follows immediately upon this; and, as mentioned, no. 137 is clearly the bottom of a strip. It is unfortunate that there is no comparable text for the partial divination statement found on no. 136: bu ci da 卜此大, “Divining about this: there will be great …” Combining the 3.2 cm from the point of the middle binding strap of no. 135 to its end with the 5.1 cm of no. 136 and the 5.1 cm of no. 137 gives 13.4 cm, 4 cm less than the proposed length of fragments no. 133 and no. 134; 4 cm would be roughly the length of four to five characters on these particular strips, perhaps about the right number to complete this divination statement. Unfortunately, we will probably never know what these characters were, and so the reconstruction remains conjectural.

FIGURE 6.9 Fuyang Zhou Yi strip no. 133, 11.8 cm long, no. 134, 3.4 cm long, no. 135, 14.6 cm long, no. 136, 5.1 cm long, and no. 137, 5.1 cm long; after Han, Fuyang Han jian “Zhou Yi” yanjiu, 11–12

Though none of the analyses presented above can be regarded as definitive, they all point to bamboo strips of about 36 cm in length. This is roughly one foot (chi 尺), six inches (cun 寸), in Han-dynasty measure. Although this is considerably shorter than Eastern Han reports that “classics” such as the Zhou Yi were to be written on strips of two feet, four inches (roughly 48 cm), and is considerably longer than Hu Pingsheng’s reconstruction of the bamboo strips at Fuyang bearing the Shi jing (again, 26 cm), that it is more or less similar to some Warring States strips bearing similar sorts of texts perhaps suggests that it is credible.31 In any event, this is what the evidence seems to suggest.

We can also try to move beyond the level of the individual strip to imagine how the entire manuscript may have looked. As I mentioned, Han Ziqiang reports that 752 or more fragments belong to the Zhou Yi manuscript, with a total of 3,119 characters. Of these, 1,110 characters belong to the basic text, and 2,009 characters belong to the divination statements. Since the total number of characters in the 450 hexagram and line statements of the Zhou Yi is 5,012, a simple proportion would suggest that the divination statements originally included upward of 10,000 characters, for an average of about 22 characters per hexagram or line statement. It would be desirable to check this average against actual cases. Unfortunately, because of the extremely fragmentary nature of the manuscript, and because of the more or less generic quality of the divination statements, making it difficult to join together fragments bearing only divination statements, it is only in extraordinary cases that such statements have been preserved or can be reconstructed in their entirety. Indeed, as far as I can tell, there are only three cases in all. I have already examined two of them: on strips 57 and 58, which pertain to the Nine in the Third line statement of Tong Ren hexagram, and strips 125 and 126, which pertain to the hexagram statement of Wu Wang hexagram. In addition to these two cases, only strips 50 and 51, which doubtless pertain to the Six in the Second line of Pi 否, “Negation,” hexagram, preserve what appears to be a complete divination statement.

50. 亨以卜大人不吉小

51. 人吉 • 六三枹羞卜雨

50. … receipt. In divining about a great man: not auspicious; about a little …

51. … man auspicious. • Six in the Third: Wrap the meat offering. Divining about rain …

Of these divination statements, the statement of nos. 57–58 includes 18 characters, that of nos. 125–26, 17 characters, and that of nos. 50–51, only 9 characters, for an average of 14.6 characters per line. Somewhat discounting the case of nos. 50–51 as an outlier, assuming an average of about 17 characters per statement would give a total of 7,650 characters in all, or about 120 characters per hexagram in the divination statements.

Strips 125 and 126, which probably constitute a complete strip except for the areas above and below the top and bottom binding straps, suggest that a complete strip would include about 45 characters. This is by no means an absolute figure, because the writing on some strips is clearly larger than that on others. However, it would seem to be a reasonable rough estimate. Combining this estimate with that above for the divination statements and also the number of characters per hexagram in the received text of the Zhou Yi (see table 6.1), which ranges from a low of 42 characters (for Dui 兑 hexagram) to a high of 107 characters (for Kun 困 hexagram), with a median number of 77 characters, would suggest the manuscript would contain somewhere between 160 and 225 characters per hexagram (42–107 characters of the basic text + 120 characters of divination statements). Divided by 45 characters per strip, this would suggest that most hexagram texts were copied on either four or five bamboo strips. Multiplying this by the sixty-four hexagrams of the text would give a total number of strips of about 290. Needless to say, this is a very rough estimate, but it is probably not too far off. If it is more or less accurate, then since the individual strips were 0.5 cm wide, if they were all bound into a single scroll, it would have been about 1.5 m long (allowing for a minimum amount of space to accommodate silk binding straps). Performing a simple experiment with modern bamboo strips of 0.5 cm in width suggests that this many strips rolled together would produce a scroll of roughly 11–12 cm in diameter, more or less similar to Hu Pingsheng’s description of the dimensions of the largest block of bamboo material from the Fuyang tomb, the one apparently containing the Zhou Yi manuscript. However, though it is an intriguing experiment to try to reconstruct the original scroll or scrolls, the fragmentary nature of the evidence would surely render any conclusion entirely hypothetical.32

| HEXAGRAM |

CHARS. |

| 1 乾 Qian |

65 |

| 2 坤 Kun |

88 |

| 3 屯 Zhun |

100 |

| 4 蒙 Meng |

85 |

| 5 需 Xu |

72 |

| 6 訟 Song |

89 |

| 7 師 Shi |

76 |

| 8 比 Bi |

77 |

| 9 小畜 Xiao Chu |

73 |

| 10 履 Lü |

69 |

| 11 泰 Tai |

94 |

| 12 否 Pi |

71 |

| 13 同人 Tong Ren |

74 |

| 14 大有 Da You |

64 |

| 15 謙 Qian |

63 |

| 16 豫 Yu |

57 |

| 17 隨 Sui |

78 |

| 18 蠱 Gu |

77 |

| 19 臨 Lin |

59 |

| 20 觀 Guan |

63 |

| 21 噬嗑 Shike |

64 |

| 22 賁 Ben |

63 |

| 23 剝 Bo |

62 |

| 24 復 Fu |

83 |

| 25 无妄 Wu Wang |

79 |

| 26 大畜 Da Chu |

61 |

| 27 頤 Yi |

81 |

| 28 大過 Da Guo |

70 |

| 29 坎 Kan |

62 |

| 30 離 Li |

79 |

| 31 咸 Xian |

58 |

| 32 恆 Heng |

57 |

| 33 遯 Dun |

62 |

| 34 大壯 Dazhuang |

68 |

| 35 晉 Jin |

83 |

| 36 明夷 Mingyi |

84 |

| 37 家人 Jiaren |

58 |

| 38 睽 Kui |

96 |

| 39 蹇 Jian |

59 |

| 40 解 Jie |

79 |

| 41 損 Sun |

101 |

| 42 益 Yi |

99 |

| 43 夬 Guai |

86 |

| 44 姤 Gou |

67 |

| 45 萃 Cui |

95 |

| 46 升 Sheng |

59 |

| 47 困 Kun |

107 |

| 48 井 Jing |

85 |

| 49 革 Ge |

76 |

| 50 鼎 Ding |

82 |

| 51 震 Zhen |

96 |

| 52 艮 Gen |

62 |

| 53 漸 Jian |

89 |

| 54 歸妹 Gui mei |

84 |

| 55 豐 Feng |

98 |

| 56 旅 Lü |

82 |

| 57 巽 Xun |

81 |

| 58 兌 Dui |

42 |

| 59 渙 Huan |

70 |

| 60 節 Jie |

63 |

| 61 中孚 Zhong fu |

77 |

| 62 小過 Xiao guo |

103 |

| 63 既濟 Ji ji |

78 |

| 64 未濟 Wei ji |

83 |

The Textual Nature of the Fuyang Manuscript

Although the bamboo strips are too fragmentary to allow any single hexagram text to be reconstructed in its entirety, much less any two hexagrams in sequence (and, thus, these materials do not provide any information regarding the sequence of the sixty-four hexagrams), by piecing together various of the fragments it is possible to determine the basic structure of the text. As demonstrated above, each hexagram text begins at the top of a strip with the hexagram picture, with yang lines drawn as 一 and yin lines drawn as ハ. Three such hexagram pictures survive (Da You 大有, “Great Offering,” no. 64, Lin 林, “Forest” [i.e., 臨, “Looking Down”], no. 86, and Li 離, “Fastening,” no. 151). The hexagram picture is followed, after a brief space apparently allowing for the top binding strap to pass, by the hexagram name, usually agreeing quite closely with the name in the received text of the Zhou Yi, though there are also the sorts of allographs and loan graphs we have come to expect from Western Han paleographic materials.33 A good example is the fragment for Lin hexagram, the hexagram name of which is written as 林 (see figure 6.2).

86.  林

林

86.  “Forest”

“Forest”

The hexagram name is followed immediately by the hexagram statement, again usually corresponding quite closely with the received text.34 A good example of this is strip 64, which contains the hexagram picture, hexagram name, and hexagram statement of Da You, “Great Offering,” hexagram.

64.  大有元亨卜雨不[雨]

大有元亨卜雨不[雨]

64.  “Great Offering”: Prime receipt. Divining about rain: it will not [rain]. …

“Great Offering”: Prime receipt. Divining about rain: it will not [rain]. …

As can be seen in this example, at the end of the hexagram statement comes a more or less protracted divination statement (distinguished in the English translation from the text that corresponds to the received text of the Zhou Yi by writing it in italics), often, as here—though not invariably—introduced with the word bu 卜, “divining.”35 The divination statement concerns whether it will rain and includes the prognostication that it will not.36 A more developed example of these divination statements is to be seen in the hexagram statement of Wu Wang 无亡, “Nothing Lost,” hexagram, examined in the previous section for what it shows concerning the physical nature of the strips.

125. 无亡元亨利貞其匪 有眚不利有攸往卜雨不雨不囗

有眚不利有攸往卜雨不雨不囗

126. 齊 不吏君不吉田魚不得 • 初九无亡往吉卜田魚得而

不吏君不吉田魚不得 • 初九无亡往吉卜田魚得而

125. Nothing Gone: Prime receipt; beneficial to determine; his not going to correct has curses; not beneficial to have someplace to go. Divining about rain: it will not rain; it will not …

126. … about clearing: it will clear; about not serving the lord: not auspicious; about hunting and fishing: you will not obtain anything. • First Nine: Nothing Gone goes; auspicious. Divining about hunting and fishing: you will obtain something and …

There are at least four different divination statements appended to this single hexagram statement: two different statements concerning the weather (whether it will rain and whether it will clear), one about serving one’s lord, and one about hunting and fishing. As I discuss toward the end of this chapter, the nature of these divination statements would seem to be more or less analogous with many of the phrases found in the hexagram and line statements of the Zhou Yi itself, such as “his not going to correct has curses” (qi fei zheng you sheng 其匪 有眚)37 and “not beneficial to have someplace to go” (bu li you you wang 不利有攸往) here (and perhaps also the “beneficial to determine” [li zhen 利貞], though this is perhaps a special case),38 and may provide some indication as to how the hexagram and line statements came into being.

有眚)37 and “not beneficial to have someplace to go” (bu li you you wang 不利有攸往) here (and perhaps also the “beneficial to determine” [li zhen 利貞], though this is perhaps a special case),38 and may provide some indication as to how the hexagram and line statements came into being.

The last phrase in these divination statements associated with the hexagram statement is followed, as here in the case of Wu Wang hexagram, by the symbol “•,” which divides it from the following line statement of the Zhou Yi proper, in this case the First Nine (chujiu 初九) line of Wu Wang. The six line statements of the hexagram then all follow the same pattern: line statement + divination statement(s) followed by the symbol “•” (though this symbol does not appear after the completion of the final “Top” [shang 上] line statement).

The Fuyang manuscript is too fragmentary to illustrate the entirety of even a single hexagram text. However, the general structure can be shown by the eleven strips that pertain to the hexagram statement and five of the six line statements of Tong Ren 同人, “Fellow Men” (hexagram 13 in the traditional sequence of the text), hexagram. To give some sense of the process involved in reconstructing the text, I first present as individual lines all eleven strips in Chinese and then follow that with an English translation that is separated into the hexagram and various line statements of the Zhou Yi (in the translation supplying missing text from the received text as needed in parentheses), and highlighting the divination statements in italics.

53. 同人于壄亨

54. 君子之貞

55. • 六二同人于宗吝卜子産不孝吏

56. 三伏戎于

57. 興卜有罪者兇

58. 戰斵遆强不得志卜病者不死乃 • 九四乘高唐弗克

• 九四乘高唐弗克

60. 人先號

61. 後笑大師

62. 相 卜

卜 囚

囚

63. 九同人于鄗无 卜居官法免

卜居官法免

53. … Fellow men in the wilds; receipt. (Beneficial to cross the great river; beneficial for a)

54. nobleman’s determination.

(First Nine: Fellow men at the gate; there is no trouble.)

55. … • Six in the Second: Fellow men at the ancestral temple; distress. Divining about a child: you will give birth, but it will not be filial; about serving …

56. (Nine in the) Third: Crouching enemies in (the grass: ascending the high mound, for three years not)

57. … arising. Divining about a guilty one: ominous …

58. … battling: the enemy will be strong but will not obtain its will; divining about someone who is sick: if they do not die then they will get better. • Nine in the Fourth: Riding on a high wall, you cannot (be attacked; auspicious.) …

59. … something will be done but not finished. • Nine in the Fifth: Fellow

60. men, first shouting,

61. later laughing; the great armies .. (can)

62. meet each other. Divining about tying a prisoner: …

63. … (Top) Nine: Fellow men in the suburbs; there is no regret. Divining about residing in office: you will be dismissed. …

Despite the fragmentary nature of these bamboo-strip texts, two things are clear: first, the text of the Zhou Yi itself corresponds very closely with that of the received text;39 and second, each hexagram and line statement is furnished with at least one divination statement, and some (such as the Nine in the Third line here) have multiple divination statements. The relationship between the Zhou Yi text and the divination statements is less clear, but their pairing was probably not random. Thus, it seems appropriate that the apparently ominous but inconclusive Nine in the Third line statement “Crouching belligerents in the grass: Ascending its high hillock, For three years not arising” should give rise to an ambivalent divination statement such as “in divining about doing battle, the enemy will be strong but will not get its way.” In the following section, I examine several more examples of Fuyang Zhou Yi line statements and divination statements, and on the basis of this examination try to draw some implications for the appearance of similar divination statements in the text of the Zhou Yi itself.

The Nature of the Divination Statements and Their Relationship to the Hexagram and Line Statements of the Zhou Yi

As demonstrated above, the divination statements in the Fuyang Zhou Yi text are usually differentiated from the Zhou Yi text itself by the introductory verb bu 卜, “to divine.”40 However, the contents of the statements are often sufficiently similar to those of the hexagram or line statement to which they are attached that if we did not have a received text against which to compare them, it would be difficult to differentiate between them. Consider, for instance, the following several examples, which illustrate different types of relationships. I again supply in parentheses the missing text from the received text of the Zhou Yi when it is relevant to the understanding.

98. • 初九屢校威 (趾无咎)

99.  囚者桎梏吉不兇 • 六二筮膚威

囚者桎梏吉不兇 • 六二筮膚威

98. … • First Nine: Frequently fettered and cutting off (a foot; there is no trouble).

99. … Tying a prisoner in fetters and handcuffs: auspicious, not ominous. • Six in the Second: Biting flesh and cutting off …

This divination statement is attached to the First Nine line of Shi zha 筮閘 (written Shi ke 噬嗑 in the received text), “Biting and Chewing,” hexagram (number 21 in the received sequence). It is easy to see that the divination statement about shackling prisoners corresponds exactly with the contents of the line statement.

120. 六二休復吉卜

121. 出妻皆復 • 六三頻

120. … Six in the Second: Successful return; auspicious. Divining …

121. … departing wives all return. • Six in the Third: Repeated …

In this case, the Six in the Second line of Fu 復, “Returning,” hexagram (number 24 in the received sequence), whatever the specific meaning of “Successful return” may have been, the prognostication that “departing wives all return” is obviously related to the major theme of “returning.”

In this case, which is the hexagram statement of Li 離, “Fastening,” hexagram, the divination statement does not begin with bu 卜, “divining.” Although there is no necessary correlation between the hexagram statement proper and either of the attached divination statements (though it would perhaps not to be too hard to see an association between the sense of “fastening,” the original sense of which is “to be caught in a net,” and the guilty man not being released [zui ren bu jie 罪人不解]), neither is there any obvious correlation with the phrase “rearing a female bovine; auspicious” (chu pin niu ji 畜牝牛吉), which is part of the original hexagram statement, and the hexagram name or the rest of the hexagram text. Indeed, it would be easy to imagine that this phrase was produced in the same context as the phrases about “residing in office and the family” (ju guan ji jia 居官及家) not being “auspicious” (bu ji 不吉) or about the “guilty man” not being “released.”

If we now consider one final example, I think it may be possible also to draw some inferences about how the original line statements of the Zhou Yi came to be formed. Fuyang strips 18 and 19 correspond to the Nine in the Second line of Meng 蒙, “Shrouded,” hexagram (number 4 in the received sequence).41

18. (九二包蒙吉納婦) 老婦吉子克

19. 家利嫁

18. (Nine in the Second: Wrapping the shroud. Auspicious. Taking a wife:) an old wife:42 auspicious; a son can

19. marry. Beneficial to marry off (a daughter) …

Given the relationship between the divination statements and hexagram or line statements suggested above it is easy to see a relationship between the divination statement “beneficial to marry off (a daughter)” (li jia 利嫁) and the line statement “the son can make a family” (zi ke jia 子克家). Indeed, if, as in the case of the hexagram statement of Li hexagram examined immediately above, there were no “divining about” here to divide the two statements, it would be easy to read the divination statement as part of the line statement. One of the most frequent formulas in the line statements of the Zhou Yi begins with the word “beneficial” (li 利): the phrases “beneficial to see the great man” (li jian da ren 利見大人), “beneficial to ford the great river” (li she da chuan 利涉大川), “beneficial to have someplace to go” (li you you wang 利有攸往) each occur numerous times, while “beneficial herewith to punish the man” (li yong xing ren 利用刑人), “beneficial to ward off robbers” (li yu kou 利禦寇), “beneficial herewith to invade and attack” (li yong qin fa 利用侵伐), “beneficial herewith to set in motion the army” (li yong xing shi 利用行師), “beneficial herewith to make an offering” (li yong ji si 利用祭祀), and numerous others each occur once or twice. The divination statement “beneficial to marry off (a daughter)” would seem to be no different in kind from all these “beneficial” formulas of the Zhou Yi. It is easy to imagine that, but for a different divination official responsible for the final editing of the Zhou Yi, this Fuyang phrase, or one much like it, could have come to be attached at the end of the Nine in the Second line statement of Meng hexagram.

It is also easy to imagine that the formulas that did make their way into the Zhou Yi derived originally from the same sort of divination context as that which produced the Fuyang text. In an important study first published in 1947, Li Jingchi 李鏡池 (1902–1975) suggested that Zhou Yi line statements are typically composed of different sorts of textual materials.43 He identified three different types or components of complete line statements: “image prognostications” (xiang zhan zhi ci 象占之辭), by which he meant such images as the various dragons (long 龍) of Qian 乾, “Vigor,” hexagram or the phrase “The withered poplar grows a sprout” (ku yang sheng ti 枯楊生稊) of the Nine in the Second line of Da Guo 大過, “Greater Surpassing,” hexagram; “narratives” (xu shi zhi ci 敘事之辭), by which he seems to have meant especially such statements involving human action as “beneficial to see the great man” of the Nine in the Second line of Qian hexagram or “The old man gets a maiden wife” (lao fu de qi nü qi 老夫得其女妻) of that same Nine in the Second line of Da Guo hexagram; and “divinations and portents” (zhen zhao zhi ci 貞兆之辭), by which he meant the various formulaic divination terms so ubiquitous in the Zhou Yi: ji 吉, “auspicious”; xiong 凶, “ominous”; li 厲, “dangerous”; lin 吝, “distress”; hui 悔, “regret”; hui wang 悔亡, “regret gone”; wu jiu 无咎, “there is no trouble”; wu you li 无攸利, “there is nothing beneficial”; wu bu li 无不利, “there is nothing not beneficial”; li zhen 利貞, “beneficial to divine,” and so on.

Although some of Li’s examples need revision,44 and the names he gave to his three categories could probably be improved, nevertheless his insight that line statements were the result of a multistep process seems to find corroboration in the Fuyang Zhou Yi divination statements. Consider the following line statements taken from the received text of the Zhou Yi, all of which contain one or more phrases strikingly similar to the divination statements of the Fuyang Zhou Yi manuscript.

屯六二屯如如如乘馬班如匪寇婚媾女子貞不字十年乃字

Zhun “Blocked” Six in the Second: Stick-stuck, carts and horses lined up; not bandits in marriage relations. Determining about a woman: not pregnant, in ten years then she is pregnant.

豫六五貞疾恆不死

Yu “Excess” Six in the Fifth: Determining: illness will be long-term, but you will not die.

隨初九官有渝貞吉出門交有功

Sui “Following” First Nine: The office will have a change. Determining: auspicious. Going out the gate to exchange has success.

Sui “Following” Six in the Third: Tie the elder man, lose the little son. Following there will be seeking to obtain. Beneficial to determine about residence.

復上六迷復凶有災眚用行師終有大敗以其國君凶至于十年不克征

Fu “Returning” Top Six: Confused return. Ominous. There are disasters and curses. Using this to move the army, in the end there will be a great defeat, together with its kingdom’s ruler. Ominous. Reaching to ten years you cannot go on campaign.

遯九三係遯有疾厲畜臣妾吉

Dun “Piglet” Nine in the Third: Tying the piglet. There is illness. Danger. Rearing servants and concubines: auspicious.

If we proceed from these rather obvious cases to one final example taken from the Fuyang Zhou Yi manuscript, we might be able to hazard a guess as to why some such divination formulas were incorporated into the received text of the Zhou Yi. Text on four separate fragments corresponds to the Nine in the Second line statement of Da Guo 大過, “Greater Surpassing,” hexagram, two parts of which were mentioned above in the discussion of Li Jingchi’s analysis of the constituent parts of a Zhou Yi line statement.

140. 不死 • 九二枯楊

141. 生 老夫得

老夫得

142. 女妻无不利卜病者不死戰鬭

143. 適强而有勝有罪而 徙

徙

140. … will not die. • Nine in the Second: The withered poplar

141. grows shoots, the old man gets ..

142. woman wife. There is nothing not beneficial. Divining about someone who is sick: he will not die; about warfare: …

143. the enemy will be strong and will have victory; about having guilt and moving away. … 45

It is easy to see how the image of this line, a withered tree growing a new sprout and an old man taking a young bride, would suggest the formula “nothing not beneficial.” There is nothing intrinsically different about that formula and the three Fuyang divination statements except perhaps their degree of specificity; it may have been nothing more than its all-encompassing generality that won “there is nothing not beneficial” inclusion in the final text of the Zhou Yi. But perhaps there was one other feature about the phrase that made it especially appropriate: the rhyme (or near rhyme) between ti/*dî  (written 稊 in the received text), “sprout,” qi/*tshəih 妻, “wife,” and li/*rih 利, “beneficial.”46 A comparison of this line with the parallel Nine in the Fifth line of the same hexagram supplies further evidence of this literary quality.47

(written 稊 in the received text), “sprout,” qi/*tshəih 妻, “wife,” and li/*rih 利, “beneficial.”46 A comparison of this line with the parallel Nine in the Fifth line of the same hexagram supplies further evidence of this literary quality.47

九五枯楊生華老婦得士夫无咎无譽

Nine in the Fifth: The withered poplar grows a flower, The old wife gets a young man. There is no trouble, there is no praise.

Whether the equivocation of this prognostication is only incidental or if it perhaps reflects some gendered criticism of an older woman who takes on a young lover is hard to say. However, especially in comparison with the Nine in the Second line it seems likely that part of the prognostication’s appeal lay in the rhyme between hua/*wrâ 華, “flower,” fu/*pa 夫, “man,” and yu/*la 譽, “praise.”48

In conclusion, the Fuyang Zhou Yi manuscript allows us to see how the Zhou Yi as we know it was used as a divination manual in the second century B.C. by at least one particular user. Perhaps more important, the divination statements attached to it also suggest some of the ways in which divination may have produced the manual itself, and through that how the Zhou Yi came to be the text that it is.

• 九四乘高唐弗克

• 九四乘高唐弗克

有眚不利有攸往卜雨不雨不

有眚不利有攸往卜雨不雨不

不吏君不吉田魚不得 • 初九无亡往吉卜田魚得而

不吏君不吉田魚不得 • 初九无亡往吉卜田魚得而 ), indicating that the character is to be read twice, presumably the first time as the topic of the divination and the second time as the predicted result, that is, “[divining about] whether it will not .. clear; it will clear.” Since the divination topic concerning rain that comes at the end of no. 125 and this one about it “clearing” are clearly related, it seems likely that no. 126 would have immediately followed no. 125. The most likely scenario for these two fragments is that they were broken at or about the top and bottom binding straps and also at the middle binding strap. This is consistent with what is seen elsewhere with bamboo-strip manuscripts. The bamboo strips were routinely notched at the points where the binding straps passed in order to keep the silk or hemp strap from sliding up and down the strip. Unfortunately, these notches tended to weaken the strips at these points, often causing them to break. If this is the case here, then the middle binding strap would have come at about 17 cm or 17.5 cm from the top of the strip, suggesting a total length for the strip of 34 cm or 35 cm, fairly close to the result obtained from the analysis of fragments 57 and 58.

), indicating that the character is to be read twice, presumably the first time as the topic of the divination and the second time as the predicted result, that is, “[divining about] whether it will not .. clear; it will clear.” Since the divination topic concerning rain that comes at the end of no. 125 and this one about it “clearing” are clearly related, it seems likely that no. 126 would have immediately followed no. 125. The most likely scenario for these two fragments is that they were broken at or about the top and bottom binding straps and also at the middle binding strap. This is consistent with what is seen elsewhere with bamboo-strip manuscripts. The bamboo strips were routinely notched at the points where the binding straps passed in order to keep the silk or hemp strap from sliding up and down the strip. Unfortunately, these notches tended to weaken the strips at these points, often causing them to break. If this is the case here, then the middle binding strap would have come at about 17 cm or 17.5 cm from the top of the strip, suggesting a total length for the strip of 34 cm or 35 cm, fairly close to the result obtained from the analysis of fragments 57 and 58.

離利貞亨畜牝牛吉居官及家不吉罪人

離利貞亨畜牝牛吉居官及家不吉罪人 Fastening: Beneficial to determine; receipt. Rearing a female bovine: auspicious. Residing in office and the family: not auspicious; about a guilty man: …

Fastening: Beneficial to determine; receipt. Rearing a female bovine: auspicious. Residing in office and the family: not auspicious; about a guilty man: …

其

其 遂

遂 无咎卜此大

无咎卜此大

林

林 “Forest”

“Forest” 大有元亨卜雨不[雨]

大有元亨卜雨不[雨] “Great Offering”: Prime receipt. Divining about rain: it will not [rain]. …

“Great Offering”: Prime receipt. Divining about rain: it will not [rain]. … 有眚不利有攸往卜雨不雨不囗

有眚不利有攸往卜雨不雨不囗 不吏君不吉田魚不得 • 初九无亡往吉卜田魚得而

不吏君不吉田魚不得 • 初九无亡往吉卜田魚得而 有眚)37 and “not beneficial to have someplace to go” (bu li you you wang 不利有攸往) here (and perhaps also the “beneficial to determine” [li zhen 利貞], though this is perhaps a special case),38 and may provide some indication as to how the hexagram and line statements came into being.

有眚)37 and “not beneficial to have someplace to go” (bu li you you wang 不利有攸往) here (and perhaps also the “beneficial to determine” [li zhen 利貞], though this is perhaps a special case),38 and may provide some indication as to how the hexagram and line statements came into being. • 九四乘高唐弗克

• 九四乘高唐弗克 卜

卜 囚

囚 卜居官法免

卜居官法免 囚者桎梏吉不兇 • 六二筮膚威

囚者桎梏吉不兇 • 六二筮膚威 離利貞亨畜牝牛吉居官及家不吉罪人

離利貞亨畜牝牛吉居官及家不吉罪人 然

然 Fastening: Beneficial to determine; receipt. Rearing a female bovine; auspicious. Residing in office and the family: not auspicious; about a guilty man: he will

Fastening: Beneficial to determine; receipt. Rearing a female bovine; auspicious. Residing in office and the family: not auspicious; about a guilty man: he will 老夫得

老夫得 徙

徙 (written 稊 in the received text), “sprout,” qi/*tshəih 妻, “wife,” and li/*rih 利, “beneficial.”46 A comparison of this line with the parallel Nine in the Fifth line of the same hexagram supplies further evidence of this literary quality.47

(written 稊 in the received text), “sprout,” qi/*tshəih 妻, “wife,” and li/*rih 利, “beneficial.”46 A comparison of this line with the parallel Nine in the Fifth line of the same hexagram supplies further evidence of this literary quality.47