4

Heartmind

1 Background: the accordance problem for Neo-Confucians and their predecessors

A major focus of the prior two chapters has been on the “formless” dimensions of Neo-Confucian thought, especially its notions of Pattern and nature. Although the Neo-Confucians think these concepts are fundamental and that it is important to get them right, they do not engage in metaphysical speculation for its own sake. Their ultimate concern in getting an accurate account of Pattern and nature is to justify their specific visions of goodness and virtue and to specify the means by which they can be achieved. Thus the Neo-Confucians paid close attention to the connections between their metaphysics and their views on moral understanding, good character, and moral cultivation. One crucial way of making these connections is by clarifying how the subjective cognitions, emotions, and inclinations of people can be made accurately to reflect and express Pattern, especially the cosmic Pattern (tianli) that gives value to the entire whole. In order to account for this alignment, they take a great deal of interest in the seat of mental and emotional phenomena which is called, in Chinese, xin 心, a term that is variously translated as “mind,” “heart,” or some combination of the two. In the most basic sense of the term, xin refers to the organ that we today call the heart but, like virtually all Chinese thinkers, Neo-Confucians take this organ to be the locus of both conation (emotions, inclinations) and cognition (understanding, beliefs). “Heartmind” expresses this unity well and is the translation we adopt in this volume. In this chapter, we focus on how the heartmind connects up with Pattern and nature. In subsequent chapters, we will discuss its relations to the emotions and examine the ways that it enables us properly to know and respond to our world.

To begin with, let us look a little more closely at one of the issues that motivates Neo-Confucians to take a philosophical interest in the heartmind. On their view, one thing that distinguishes Confucianism from rival schools of thought is that Confucian ethics and methods of moral cultivation help to create a heartmind that is responsive to Pattern rather than to contingent and subjective whims and inclinations. Daoxue philosophers like Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi identify this as a major point of departure from Buddhism, and a mark of Confucianism's commitment to the greater good.1 To show how we can develop heartminds that accord with Pattern, however, we need to know something about the nature and function of the heartmind as such: how it comes to have intentions and emotions that do or do not track the larger world and its underlying structure. Let us call this set of issues the “accordance problem.”

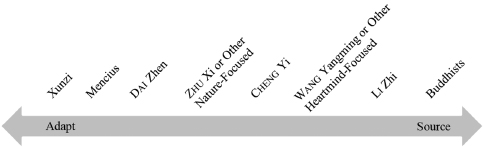

Simplifying somewhat, we could put most answers somewhere along a spectrum. At one end is the view that the heartmind's primary role consists in adjusting itself to fit norms that are independent of it, much as we may revise our beliefs or feelings in light of new evidence. But this is not the only way to bring moral norms and the heartmind into accordance. At the other end of the spectrum, some instead say that the heartmind is itself a source or basis of the norms, so that the norms are, in some sense and to some degree, already aligned with the heartmind just by their nature. For example, a young person might be required to treat an elder with respect because respect for elders is part of the deep structure of her thinking and emotions. Perhaps the very status of the other person as an elder, or even as a person, is a product of her heartmind. For ease of reference, we will say that the first sort of answer makes it the heartmind's task to adapt to externally given norms, and the second sort of answer makes the heartmind a source of those norms. To preview where some of the philosophers we discuss in this chapter fit on such a spectrum, see Figure 4.1.

Even at this general level of description, we can begin to see why both sorts of answers might be problematic. If we want to solve the accordance problem by saying that the heartmind is a source of moral norms, then we will have trouble justifying corrections to the emotions, desires, and thoughts that our heartminds are already predisposed to have. If we think there is something wrong with a father's inclination to abandon his young children and elderly parents, we would need some way of explaining why this inclination is wrong. Let us call this the problem of finding an independent standard of assessment. If one thinks that a given heartmind's reactions (i.e., emotions, desires, or thoughts) are incorrect, on what basis can they be criticized? If the only standard of assessment is the heartmind's reactions themselves, this seems too subjective, without any independence whatsoever. As we will see, there are possible responses to this challenge, some of which are adopted by the Neo-Confucians themselves, but it represents a worry that looms large in Neo-Confucian discourse.

Appeals to the adaptability of the heartmind may also be problematic. Most obvious is that the heartmind seems to be riddled with powerful emotions, attachments, and cognitive predispositions that set barriers – perhaps insurmountable ones – to its powers of adaptation. For example, no matter how much we may aspire to love everyone equally, it seems nearly impossible to avoid loving members of our own family more than people completely unknown to us. Another limitation is more subtle. Let us say that virtuous people are more wholeheartedly invested in their thinking and behavior than are people who merely follow the rules. A virtuous youth does not just respect her elders because it is required; she respects them because she has powerful aversions to seeing her elders treated with disdain, because she takes joy in seeing them treated respectfully, and because she understands at a deep level how respect for elders maintains a kind of social harmony and, ultimately, contributes to ongoing life-generativity. Without wholeheartedness, furthermore, she may have only a thin and fragmentary understanding of how to show proper respect, and consequently she may experience uncomfortable doubts about her actions. Perhaps the heartmind's powers of adaptation might be stretched to fulfill everything demanded of it, but it is hard to see how it could have the strong, thoroughgoing cognitive grasp and emotional investment in this way of life if these demands are completely detached from its own internal constitution. Neo-Confucians are particularly concerned about this latter limitation, which we can call the problem of wholeheartedness. To sum up, then, the accordance problem has two basic types of answers (setting aside for now efforts to stake out middle positions): adapt the heartmind to norms, which then faces worries about wholeheartedness, or understand the heartmind as the source of norms, which then faces worries about independent standards of assessment.

Both sorts of answers had precedents in Chinese philosophy before Neo-Confucianism, and the Neo-Confucians gave voice to all of the above criticisms and concerns about these sorts of answers. Probably the most notable defender of the adaptation view was Xunzi, the classical Confucian who proposed that the heartmind in its original state is largely bad, but nevertheless can be brought to “approve” (ke 可) practices that it perceives as in accordance with the Way, a process which can over time reshape one's emotions and desires.2 Thus, on Xunzi's view, the heartmind is not itself a source of norms but is expected to adjust to and reflect them.3 With some exceptions in the Qing dynasty, most Neo-Confucians considered Xunzi an outlier to the Confucian tradition,4 and they objected to him in part because they thought it impossible for us to develop virtues that are wholehearted, sincere, and have the requisite degree of self-confidence unless our heartminds have an underlying deep structure and source of control that is good to start with.5 Many Neo-Confucians also thought that there were certain insurmountable limits to the sort of emotions and desires a heartmind might express. For example, all people form special attachments that resemble in crucial ways one's attachments to parents and siblings, so that even monks who aspire to leave family relationships behind entirely nevertheless develop ersatz parents and siblings in their monastic communities.6

Some forms of Chinese Buddhism offer answers to the accordance problem that look to be at the far end of the “source” side of the spectrum, proposing that the heartmind is a source not only of norms but also, in some sense, of the world itself.7 This position – or perhaps just an uncharitable misreading of it – becomes a kind of reductio ad absurdum for many Neo-Confucians. One of the most widely invoked criticisms of Buddhism is thus to suggest that it treats certain matters of fundamental importance as based merely on the contingencies of one's own psychology, suggesting that whether one should or should not serve and care for one's parents depends on whether one happens to feel like it, or even on whether one happens to have the relevant desires and emotions. For many Neo-Confucians, this view was not just dangerous but based on a mistaken understanding of the nature of ethics, for (they thought) the Buddhist view countenances emotions and behaviors that pay little heed of more objective considerations like the ethical value of care, the needs of one's parents, and so on. In contrast with the radical subjectivism that they find in Buddhism, the Neo-Confucians tend to highlight the fact that ethics is properly grounded in the cosmos (tian 天), emphasizing that the cosmos is by its very nature something that is not up to us or open to the whims of personal interpretation.

The early Daoxue thinker Cheng Yi declares that Confucian “sages base themselves on the cosmos, while the Buddhists base themselves on the heartmind.”8 As is apparent to Cheng's contemporaries and students, this is another way of saying that the Confucians stand for objectivism against Buddhist subjectivism, seeking beyond the emotions and perceptions that our heartminds happen to have for a deeper basis for standards and norms. That is, it is a way of saying that Confucians, unlike Buddhists, offer an independent standard of assessment, and that standard closely tracks the larger, objective world (the cosmos). A student of Cheng Yi's makes much the same point when he argues that “What the Buddhists call ‘nature’ is what the sages call ‘heartmind’; what the Buddhists call ‘heartmind’ is what the sages call ‘intention.’ ”9 On this view, Buddhists lack a genuinely objective notion like the Confucian understanding of “nature.” The Buddhist version of nature, on this account, is really only what the Confucians view as the heartmind – something that is less objective than nature, but more objective than mere occurrent “intentions” (yi).

To be sure, answers to the accordance problem that propose to treat heartmind as a source will vary a great deal, admitting of different types and different degrees. The most extreme version of this would be to identify Pattern itself with our actual, current motivational set (and our actual set of emotional reactions): this is a kind of ethical subjectivism since ethical norms are identical to one's own subjective reactions. In fact, we saw in chapter 3 that influential Chan Buddhists took a position that resembles this radical view, or at least the monk Zongmi worried about it and criticized such a tendency among his peers. Those Neo-Confucians tempted by a “source” view usually take a less extreme position, suggesting that Pattern is identical to the heartmind in a certain fundamental phase or state, usually labeled the “inherent” (ben) state independent of or prior to stimulation and distortion by external things. A third option is to suggest that norms arise not from the heartmind in any phase or state presently available to it, but rather to the heartmind as it would naturally develop if given a healthy environment in which to grow. So, for example, it might be that we should respect our elders not because we currently have heartminds that predispose us to respect them (in some more fundamental phase or state) but because our heartminds would feel respect for elders if allowed to develop naturally, much as a peach pit would eventually be able to produce other peaches if allowed to develop naturally.10 This sort of view, although more qualified, still treats the heartmind as a source of norms, and in fact it lines up rather neatly with a view held by the classical Confucian philosopher Mencius.11

2 Identifying heartmind with Pattern

Generally speaking, most Neo-Confucians rejected Xunzi's extreme version of the view that it is the heartmind's function to adapt to norms given to it externally. But as noted above, they also were worried about Buddhist views that turned heartmind into a source of norms, a view that appeared to them to verge on pernicious subjectivism. For many Daoxue Confucians, an appealing way to avoid both of these unhappy alternatives was to maintain that norms were in some important sense internal to the heartmind, and yet not merely dependent on the contingent and subjectively variant psychological phenomena that people happen to have. They could do this by proposing that, in some sense, the heartmind is identical to Pattern. This move is characteristic of what we call a heartmind focus. On this view, the heartmind is not fully a source of norms because it is not more fundamental than Pattern, but it nevertheless has norms internally rather than externally. In this section, we will canvass the Daoxue theories that attempt to explain this relation between heartmind and Pattern, beginning with the somewhat ambiguous stance of Cheng Yi and then moving on to three thinkers who strongly identify heartmind and Pattern.

Cheng Yi's view depends on using “heartmind” in two different ways. On the one hand, there is our physical heartmind, which has “form,” can be mistaken or biased and is limited in its scope. On the other hand, Cheng Yi also uses heartmind in a formless sense, closely identified with Pattern, which is unlimited in capacity and necessarily good. Consider the following:

Someone asked: “The human form is limited; is the heartmind similarly limited?” Cheng Yi replied: “If you are speaking of the heartmind's form, how could it not have limits?” “Is the marvelous functioning of the heartmind also limited?” Cheng Yi replied: “From the perspective of one's being human, there are limits. Limited form and limited vital stuff mean that functions cannot connect to everything. With respect to the Way, then, how could there not be limits? Mencius said, ‘To fully fathom one's heartmind is to understand one's nature.’ Heartmind just is nature. With respect to the cosmos, it is the decree; with respect to humans, it is nature; when speaking of its ability to be master, it is heartmind; but these are all a single Way. If one can connect them all with the Way, then what limits are there?”12

Elsewhere, Cheng also says that “Pattern and heartmind are one; it is just that people cannot understand that they are one.”13 If heartmind is the same as nature (as in the first passage) or Pattern (as in the second), though, why do we need the notion of heartmind at all? A possible answer lies in the first passage's reference to mastery. Somehow the heartmind explains how we humans, unlike other aspects of the cosmos (animals, plants, and other things), are able to transform ourselves to become the flawless moral agent that is a sage. Thus by talking about the heartmind in the formless and unlimited sense, we refer not just to the underlying source of order and value for things in general (Pattern or cosmic Pattern), but more specifically to the power of that source to win control over unruly intentions and emotions – in a word, mastery.

If we are to understand our capacity for mastery and agency, though, we need to understand the connection between the limited, physical heartmind that we experience, and the heartmind that is equivalent to nature and to Pattern. Does speaking of these two different senses of heartmind help to explain our ability to transform? Cheng Yi attempts to address this question by invoking what had been an obscure passage from the Book of Documents. The original passage reads: “The human heartmind is precarious; the Way heartmind is subtle. Be discriminating and undivided, that you may hold fast to the center.”14 In one of his comments on this text, Cheng Yi associates the “human heartmind” with “selfish desires” and thus with danger, and the “Way heartmind” with cosmic Pattern, and thus with subtlety and profundity. He adds: “Eliminate selfish desires and cosmic Pattern will shine forth.”15 One might wonder, though, where the “control” aspect of the heartmind figures in this explanation. The “human heartmind” seems to be simply problematic, while the “Way heartmind” seems to function automatically, once the human heartmind has been removed, suppressed, or otherwise brought in accord with the Way heartmind. Is there room for agency here? Perhaps control is exercised in the very process of eliminating selfish desires, but what is it that exercises such control? It is tempting to reply that it is the heartmind, but which one, or which aspect? As we will see in a later chapter, Cheng Yi has influential teachings about how we are to change ourselves, but he has very little to say about how our heartmind, under some description, can be imperfect, improvable, and yet contribute positively to its own improvement. We will see later in this chapter, though, that Zhu Xi may have a more satisfactory explanation for the nature of and relation between human and Way heartminds.

In order to understand the range of things that Neo-Confucians mean when they equate the heartmind and Pattern, let us spend a moment here on the idea of “inherent heartmind” (benxin). This term is used only a few times in the classical era, including once in the Mencius, when he criticizes those who have “lost” their benxin. The meaning of the word ben, which we translate as “inherent,” also includes the idea of “root,” and benxin in the Mencius is often translated as “original” heartmind. This is definitely not apt for the many Buddhist and Neo-Confucian appropriations of the term, however. The problem with “original” is its implication that the heartmind was a certain way, and now it is not. When Buddhists talk about the inherent heartmind, they refer to something about the heartmind that is never lost: it is an aspect of the heartmind, or a perspective on the heartmind, that is always with us, even if we do not see it. When Neo-Confucians begin to pick up the term, the same general point applies to them as well: “inherent heartmind” refers to the enduring, inherent capacity of one's heartmind to function in normatively positive ways.16

Understanding the idea of inherent heartmind is important because it allows us to see one way in which thinkers who say that “heartmind is Pattern” are still striving to achieve a kind of independent standard of assessment, while at the same time believing they have answered worries about wholeheartedness. Given the close ties between heartmind and Pattern in Cheng Yi's writings (as well as in those of his brother Cheng Hao17), it should be no surprise that many of his students and their students also develop similar themes to an even greater degree.18 The best example is probably Zhang Jiucheng. He explicitly asserts that “heartmind is Pattern, and Pattern is heartmind”; even more strikingly, Zhang also equates the heartmind and cosmos.19 Now the idea that there is an interdependence between humans and the cosmos is certainly not new, but Zhang's assertion that the heartmind is the key fulcrum to the interdependence has few precedents in Confucian writings, and erases the distinction between cosmos and heartmind that Cheng Yi was struggling to draw.20 Zhang is not claiming that there is no actual cosmos – that somehow the cosmos just exists in our heartminds – but rather that there is no meaning or value in the cosmos independent from the inherent heartmind, which is in some sense shared throughout the cosmos. This commonality of the inherent heartmind is what provides for objectivity and thus for an independent standard of assessment: Pattern is not identical with just any set of responses one happens to have but with the eternally existing inherent heartmind. Of course, this may raise as many questions as it answers: for instance, where and what is this inherent heartmind, and how do we access it? Without some answers, we are no better off than we were with Cheng Yi's distinction between human heartmind and Way heartmind. Here, too, Zhang Jiucheng has a provocative response. Recall from chapter 3 the distinction between “not yet manifest” and “already manifest.” Zhang believes that true meaning and value are grounded in our “not-yet-manifest” heartmind, which is our inherent heartmind. Zhang is therefore one of the key advocates of an approach to self-cultivation according to which one focuses attention on this “unseen and unheard” state within oneself. That is, one tries to grasp this purity and then retain it as one moves into activity, which might provide for the needed sense of wholeheartedness, as we discuss in detail in chapter 7. For now, what is important is that Zhang's answer to the question “what is the inherent heartmind?” is as follows: it is the not-yet-manifest heartmind in its pure tranquillity.

Like Zhang, Lu Xiangshan effectively collapses Cheng Yi's distinction between cosmos and heartmind (though he uses the term “universe” instead of “cosmos”), asserting that “the universe is my heartmind; my heartmind is the universe.”21 He also objects to Cheng Yi's distinction between the “human heartmind” and the “Way heartmind”; for Lu Xiangshan, this distinction led one to downplay the importance of one's very own heartmind, with precisely the negative consequences that we earlier identified as following upon a lack of wholeheartedness. First, one looks to external standards of value (such as the classics) which themselves are only murky traces of the early sages' own heartminds, instead of the pure source and standard that exists within oneself. Second, the possibility that one can become a sage, in complete harmony with the cosmos, is lessened to the extent that self-cultivation becomes a process of gradually trying to piece together ideas and values from outside oneself.22 So far, Lu's account of heartmind closely approximates Zhang's, but we see a significant departure from Zhang on another important issue. Unlike Zhang, Lu does not insist that we identify Pattern with heartmind only in its tranquil, not-yet-manifest phase. On the contrary, according to Lu, Pattern is to be found in activity as well:

to claim that tranquility alone is cosmic nature – does this imply that movement is not an expression of cosmic nature? The Book of Documents says, ‘The human heartmind is precarious. The Way heartmind is subtle.’ Many commentators understand the ‘human heartmind’ to mean human desires and the ‘Way heartmind’ to mean cosmic Pattern. But this is wrong. There is only one heartmind. How could humans have two heartminds?23

If there is only one heartmind, though, then what can the “inherent heartmind” refer to? As we understand it, Lu's position is this: the inherent heartmind, which is always with us, is simply the (one) heartmind insofar as it is responding perfectly spontaneously, perfectly impartially, to a particular stimulus in the actual world. How to get oneself to respond spontaneously and impartially is a matter for discussion in chapter 7. Here, the key is to see how Lu might think that equating Pattern with the inherent heartmind will lead to wholeheartedness: the impartial deliverances of one's own heartmind are perfectly concrete and clear, shaped precisely to deal with the particular nuances of whatever situation one is encountering. This brings us to one final feature of Lu's view: namely, he, like Wang Yangming, holds that standards of right and wrong, or good and bad, vary according to context, so that no standards apply across all contexts. While Lu does not entirely reject the value of texts and teachers, he emphasizes that any past attempt to crystalize Pattern in writing refers to that particular situation and cannot be inflexibly applied to any new situation.24

The best-known advocate of identifying heartmind and Pattern is Wang Yangming, the dominant figure of Ming dynasty Neo-Confucianism. Wang adds some important nuances to the arguments we have just seen, and several of Wang's key teachings that we discuss in other chapters – such as the role of “good knowing” (chapter 5) and the “unity of knowing and acting” (chapter 6) – are undergirded by his argument that there is no Pattern apart from the heartmind. When one of his students suggests that, in our interactions with others, there are various Patterns that it would behoove us to investigate, Wang replies:

In the matter of serving one's parents, it will not do to seek a Pattern of filial piety in one's parents, and in the matter of serving one's ruler, it will not do to seek a Pattern of devotion in one's ruler. … They are all in this heartmind; heartmind is Pattern. When the heartmind is free from all obscuration by selfish desires, it just is cosmic Pattern, which requires not an iota added from the outside.25

It should be clear why, when Wang discovered the writings of Lu Xiangshan rather late in Wang's life, he felt that he had discovered a kindred spirit. Recall our discussion in chapter 3 of Wang's rejection of the view that there are ethical rules that apply across all contexts. In the context of explaining why he holds that the inherent reality of the heartmind is “beyond good and bad,” we mentioned Wang's discussion of the sage Shun's decision about whether to marry. Wang argues that Shun's proper (“good”) reaction establishes no rule (which would be an external, rigid “good”) that can now be followed ever after. Similarly, in the passage about serving one's parents cited above, we should not look for a Pattern outside us, but rather attend to how our heartmind guides us. Good and bad emerge, that is, from the functionings of the heartmind, which itself is prior to our external determinations of good and bad. Wang takes the implication of this identification of heartmind and Pattern very seriously. A student asks him what he makes of Cheng Yi's statement that “What is in a thing is Pattern.” Wang replies: “The word ‘heartmind’ should be added, so that it reads: ‘When heartmind is engaged in a thing, there is Pattern.’ For example, when this heartmind is engaged in serving one's parent, there is filial piety.”26 In other words, a thing in itself, disconnected from any heartmind, would be Patternless.

Indeed, the tight relationship between the heartmind's engagement with things and the existence of Pattern has led some interpreters to read Wang as an idealist – that is, as believing that the world depends for its existence on the activity or functioning of the heartmind, and thus is in some sense a creation of our consciousness or subjectivity. The passage most often cited in support of this reading runs as follows:

What emanates from the heartmind is the intention. The inherent reality of intention is knowing, and wherever the intention is directed is a thing. For example, when one's intention is directed toward serving one's parents, then serving one's parents is a ‘thing.’ When one's intention is directed toward serving one's ruler, then serving one's ruler is a ‘thing.’ … Therefore I say that there are neither things nor Patterns outside of the heartmind.27

If we take it out of context, “there are neither things nor Patterns outside of the heartmind” certainly sounds like idealism. But here Wang seems to be talking about “things” in a technical sense, understood as objects of consciousness. In a separate dialogue, one of Wang's friends presses him to clarify his view. His response suggests that he readily acknowledges the heartmind-independence of things in the more ordinary sense, although he seems little interested in their heartmind-independent state:

The master was strolling in the mountains of Nan Zhen when a friend pointed to the flowering tress on a nearby cliff and said, “If in all the world, there is no Pattern outside the heartmind, what do you say about these flowering trees, which blossom and drop their flowers on their own, deep in the mountains? What have they to do with my heartmind?”

The master said, “Before you looked at these flowers they along with your heartmind had reverted to a state of silence and solitude (ji 寂). When you came and looked upon these flowers, their colors became clear. This shows that these flowers are not outside your heartmind.”28

As we see here, Wang acknowledges that there is a sense in which the flowers exist on their own, independently of the heartmind; this is the flowers in a state of “silence and solitude.” But Wang's concern is to correctly grasp not the flowers themselves but rather the Pattern of the flowers, which he indicates by speaking of how the colors of those flowers become clear. This is the point at which the flowers acquire meaning and value for us, and the meaning and value of the flowers do not lie in the flowers alone but only in the interaction between the flowers and one's heartmind.29

One problem that we have been tracking throughout this chapter is that of identifying an independent standard of assessment, one that would put us in a position to criticize and revise the intentions and emotions that we happen to have. Do the several versions of the view that “heartmind is Pattern” that we have just examined have satisfactory responses to this problem? If Pattern is related to heartmind in the way that Wang proposes, on what basis could we assess, for example, a father's seemingly natural inclination to abandon his children? How can he show that such an inclination is only a contingent and personal feature of the father's heartmind, rather than an inclination warranted by considerations of Pattern? Here, we can point to two lines of response available to Wang Yangming. The first line of response is that the father in question is too selfish. He sees himself as standing outside of the larger whole and has an exaggerated sense of his own importance and too little sense of the importance of his children. Wang readily acknowledges that many of our psychological reactions can go awry, and he blames selfish desires (si yu 私欲) and selfish intentions (si yi 私意) for this problem.30 The second response is that even extended work at removing selfishness is no guarantee that one will respond correctly, but, as we will see in the next chapter, Wang deploys an idea he terms “good knowing” to explain how objective Pattern insistently calls itself to our attention.

3 Zhu Xi on nature, emotions, and the heartmind

We turn now to Zhu Xi, whose account of the heartmind is explicitly designed to avoid two sorts of extremes: those that insist too strongly on heartmind as the “source” of Pattern and those that identify heartmind too closely with vital stuff (which often goes hand in hand with an emphasis on the need to “adapt” the heartmind). On the one hand, he holds that views like those who collapse the distinction between heartmind and Pattern – and here he names Lu Xiangshan and Zhang Jiucheng – seem to eliminate the possibility of actual psychological guidance from our heartminds. He also worries that it might lead to a Buddhist subjectivism, according to which nature, Pattern, and the whole cosmos lose their objectivity, becoming simply inventions of our subjective heartminds. He insists that “heaven and earth are inherently existing things; they are not created by our heartminds.”31 On the other hand, Zhu is also not happy to think of the heartmind as simply the physical organ or the contingent emotions that it happens to have at a given time. He regularly uses the term “inherent heartmind” and also emphasizes the “Way heartmind” (recall that Cheng Yi had earlier called attention to this idea, as discussed above), thus ascribing to the heartmind a certain independence from the contingent state of one's vital stuff.

Zhu defends a middle position which, in his view, avoids the hazards of each of the two extremes, and to express this position he borrows a phrase from the earlier Neo-Confucian Zhang Zai: “the heartmind unites nature and emotion.”32 Zhu means that the heartmind is the crucial nexus that brings together our formless nature and our contingent, empirical emotions, but how does it do this? What sort of “uniting” (tong 統) does Zhu have in mind? There is considerable scholarly controversy here, with some influential voices claiming that Zhu understands the heartmind as simply vital stuff: that is, as an empirical entity capable of grasping empirical truths. However, in light of both specific statements that Zhu makes to the contrary, and our overall understanding of Zhu's philosophical position, we believe that Zhu cannot hold that the heartmind is simply vital stuff.33 Instead, we find the recent interpretation of Michiaki Fuji – which builds on the work of a range of other scholars – to be compelling.34 Fuji argues that Zhu's view is that the nature and the emotions mutually constitute one another, and that this process of mutual constitution is the heartmind. So heartmind is neither Pattern nor vital stuff alone.

Let us explain. Recall from above the distinction between the not yet manifest – the realm of nature, centeredness, Pattern – and the already manifest, where we find emotion. Zhu says that the “heartmind is not placed between the already manifest and the not yet manifest; it is both, through-and-through.”35 How, then, do we interpret Zhu's statements that the “heartmind possesses (ju 具) Pattern,” “heartmind includes (bao 包) nature,” and “Pattern is just in the midst of heartmind”? As Fuji emphasizes, the answer is not to envision an actual space inside of the heartmind where Pattern/nature is located, even though Zhu does on rare occasion say things that might suggest this.36 Instead, it helps to think in terms of processes rather than spaces. The ongoing process of the not yet manifest becoming manifest – which we just saw Zhu identify with the heartmind – can also be understood as the process of emotions emerging from nature. As we explained in chapter 3, nature is a kind of directionality or centeredness. It is present throughout the process of our emotions being manifested in response to a given stimulus, even when our response is ultimately inapt or off-center (i.e., bad). Putting this all together, we can say that the heartmind is really a process: it is the emotions continuously emerging under the (often partial) direction of nature. Fuji suggests that the heartmind can be understood diagrammatically as follows:

This conception of the heartmind is made explicit by Zhu Xi's student Chen Chun, who says that only when Pattern (nature) and qi (emotions) come together do we have heartmind. Chen adds that if we were to follow the Buddhists and eliminate emotion, then only “dead” nature would be left.38 Nature is “live” through being part of the heartmind's continuous responses to the world.

In the next chapter, we explore the conative, cognitive, and perceptual dimensions of the dynamic interactions between nature and emotions that make up the heartmind. To wrap up this discussion of the metaphysics of Zhu Xi's heartmind, we turn now to his development of the terms “Way heartmind” and “human heartmind.” Recall from above that Cheng Yi introduced these terms in an effort to explain how his two senses of “heartmind” might interact with one another. The first thing to understand for Zhu Xi is that the “Way heartmind” is not equivalent to Pattern, as it had been for Cheng Yi. Instead, both human heartmind and Way heartmind are “already manifest,” which – given what we have just seen about Zhu's understanding of the heartmind – only makes sense if they are both supposed genuinely to be ways of talking about the heartmind, since the heartmind cannot be disconnected from the manifesting of emotion.39 So what is the difference between these two ways of talking? Zhu Xi explains:

The heartmind is one. When we speak of it from the perspective of its containing cosmic Pattern and its spontaneous manifestation in each circumstance, we call it “Way heartmind.” From the perspective of having goals and conscious motives, we call it “human heartmind.” Now having goals and conscious motives is not always bad. We still call it “selfish desire,” though, since it is not completely spontaneously manifesting from cosmic Pattern.40

Zhu adds that if one can reach the point of no comparison and calculation, such that one's reactions are wholly in accord with the “pervasive circulation of Cosmic Pattern,” then this is the “human heartmind with the consciousness of the Way heartmind.” In another place, Zhu calls this the “human heartmind being transformed into the Way heartmind.”41 As the contemporary scholar Chen Lai emphasizes, such a transformation does not mean that one has been purged of emotions. Instead, as Zhu Xi himself puts it, “when the human heartmind and Way heartmind are unified, it is as if that human heartmind had disappeared.”42 One still has emotions, but they do not give oneself any inappropriate weight. More concretely, Zhu puts it this way: “Take the case of food. When one is hungry or thirsty and desires to eat one's fill, that is the human heartmind. However, there must be moral Pattern in it. There are times one should eat and times one should not. … This is the correctness of the Way heartmind.”43 Whenever one's desires to eat spontaneously match up with Pattern, that is a human heartmind that has been transformed into the Way heartmind.

Throughout this chapter, we have been viewing theories of heartmind via the problem of “accordance”: how is one's heartmind – and thus the actual reactions one has to the world – able to accord with Pattern? We saw above that the accordance problem has two basic types of answers: adapt the heartmind to norms, which then presents worries about wholeheartedness, or understand the heartmind as the source of norms, which then presents worries about independent standards. Zhu Xi's answer leans more in the “adapt” direction than do those Neo-Confucians who assert an equivalence between heartmind and Pattern, so it is fair to ask whether Zhu's approach leaves us unable to wholeheartedly embrace Pattern. Zhu's answer would be to deny that he draws too firm a line between Pattern and the heartmind. Even though it is usually imperfectly realized, the nature of each of our heartminds is, still, cosmic Pattern and, as we have just seen, it is possible for one to transform one's heartmind so that it is the “Way heartmind,” perfectly expressing Pattern. Zhu believes that this process of transformation is lengthy and demands that we pay attention to external sources of learning and authority. But he insists that learning can transcend merely superficial adaptations to external standards and attain wholeheartedness, his term for which is “sincerity” (cheng 誠), which we discuss in chapter 8.44

4 Late Ming and Qing developments: to the extremes

Until now, we have largely focused on leading thinkers in Song and Ming dynasty Daoxue. But beginning in the late Ming and culminating in the mid-Qing, Neo-Confucianism grew increasingly pluralistic and began to experiment with a wider range of views, and this applies especially to their thinking about heartmind. In this section, we will look briefly at some notable views outside the mainstream. The first two come from what has come to be called the Taizhou School of Daoxue, which refers to a group of sixteenth-century thinkers whose intellectual lineage can be traced back to Wang Yangming, but who took Wang's views in more radical directions. For example, major figures in the Taizhou School taught tradespeople and other commoners and (as we will see in chapter 8) defended more equal treatment of women. Two influential Taizhou Neo-Confucians, Luo Rufang and Li Zhi, stand out for proposing that the idea of an “inherent heartmind” be understood as referring to the heartminds that people have before their ideas and emotional dispositions are reshaped by the usual social influences that we take on as we grow up. Like Wang Yangming and others, they embraced the idea that the benxin, which we have been translating as “inherent heartmind,” is identical to Pattern, but unlike Wang they took the phrase in the somewhat more literal sense of “original heartmind.” Luo praised what he called the “infant's heartmind” (chizi zhi xin 赤子之心), seen paradigmatically in, for example, the infant's love of nourishment and her parent's affection.45 Li used somewhat similar language in a famous treatise on the “child's heartmind” (tongxin 童心). Li directly identifies Pattern with the inherent heartmind, and then the inherent heartmind with the child's heartmind, emphasizing that the psychological dispositions of children have not yet been changed by external forces:

From the beginning, aural and visual impressions enter in through the ears and eyes. When one allows them to dominate what is within oneself, then the child's heartmind is lost. As one grows older, one hears and sees what society regards as “moral principles” (daoli 道理). When one allows these to dominate what is within oneself, then the child's heartmind is lost. As one grows older, the moral principles that one hears and sees grow more numerous with each day, thus extending the breadth of what one “knows” and “feels.” Thereupon, one realizes that one should covet a good reputation, and endeavor to enhance it. One then loses one's child's heartmind.46

Not surprisingly for two philosophers who connected Pattern to youthful minds, both Luo and Li resisted the view, popular in Daoxue and beyond, that one should strive to suppress or contain one's spontaneous emotions, and both explicitly embraced the heartmind's natural tendency to seek pleasure and joy, although Luo sometimes suggested that it should not be something we seek deliberately or self-consciously.47

Luo's and Li's accounts again face the problem of identifying an independent standard of assessment but, arguably, in a more forceful way than before because the techniques that other Daoxue Confucians recommend for purging us of our bad desires – e.g., reading the classics, eliminating selfishness – seem harder to apply in a manner consistent with maintaining the spontaneous emotional responses of a child. In certain respects, Li's account poses the greater challenge here. Luo, at least, assumes that the basic emotions of the infant's heartmind are the same across all people, and he thinks those emotions line up neatly with traditional Confucian virtues such as filial piety and parental affection. In contrast, Li, following Wang Yangming, embraces the view that there are no rules of right and wrong that apply across all contexts.48 He argues that the genuine (zhen 真) emotional responses vary from one individual and context to the next, and he is more willing to accept departures from Confucian practices and values when they better reflect what he takes to be the genuine inclinations of the child's heartmind.49 In the eyes of one contemporary scholar, at least, Li's view provides us with too little by which to judge what appear to be unabashedly selfish emotions and desires, except by appealing to standards set by a phase of the heartmind – the child's one – that is impossible for social creatures like us to reclaim.50

At the outset of this chapter, we discussed two sorts of solutions to the accordance problem, one of which makes it the function of the heartmind to adapt to norms given externally and the other of which makes the heartmind a source of norms. It is striking that, up to this point, most of the Daoxue Confucians that we have canvassed attempt to solve the accordance problem by either directly identifying heartmind with Pattern or by proposing that Pattern is a major constituent of the heartmind. In the Qing dynasty, however, major Neo-Confucian philosophers articulate positions closer to the other end of the spectrum. For example, Dai Zhen saw the heartmind as having a natural but still largely undeveloped affinity for Pattern. This is in large part because he thinks it natural for all sentient creatures to love life and life fulfillment – beginning with their own but, for the more intelligent creatures, extending to the life in others as their sphere of awareness expands to include others.51 In direct opposition to the Daoxue philosophers, Dai also insists that the heartmind is, at bottom, constituted solely by vital stuff and capable of tracking Pattern only insofar as it acquires the virtues and intellectual faculties that enable it to support an orderly process of life-giving generativity. Another unorthodox Neo-Confucian to adopt a more Mencian conception of heartmind is Wang Fuzhi. Like Dai, he sees the heartmind and its constituents as reducible to vital stuff, in his case the most energetic and refined vital stuff.52 Wang also explicitly contrasts his view with that of mainstream Daoxue philosophers, adopting the by then popular Daoxue distinction between the human heartmind and the Way heartmind, but proposing that the Way heartmind is a more developed variant of the former, rather than something independently grounded in Pattern.53 Both of these important Neo-Confucians attest to depth and diversity of Neo-Confucian thought on the heartmind.