Meyerhold with Konstantin and Tatiana

It had taken an hour to unload the luggage and say goodbye to the actors, stagehands and technicians. Meyerhold had been caught up in the back-slapping and handshakes. For Zinaida, waiting with her parents and children, it had been agonising. Her resolution, so strong when she arrived at the station, had weakened with each glance, each smile Meyerhold had given her. The children’s joy at seeing him had persuaded her to wait until they got home.

The six of them had taken a cab to the apartment on Bryusov Lane. Meyerhold had paid the driver to carry up the trunks and suitcases.

‘This one here, comrade,’ he said, pointing to a large leather bag. ‘That’s the important one.’

Meyerhold called for silence.

‘And now, comrades, citizens, Madame, boys and girls, we have the official distribution of presents, gathered, I may say, with no regard to expense or effort, from every corner of our fine and fabled land!’

The children squealed with delight. They threw themselves on Meyerhold with hugs and kisses.

Meyerhold with Konstantin and Tatiana

Sergei had been arrested before. The pranks and scandals of the Imagists had stirred up public indignation. But the times were different now. The political climate was harsher; the regime was smiting its enemies.

Sergei Yesenin, Alexei Ganin and twelve others were charged with belonging to an illegal organisation dedicated to the overthrow of the legitimate government of the Soviet Union. Like them, nearly all the accused were poets or artists.

Pyotr Chekrygin, age 23, poet

Nikolai Chekrygin, 22, poet

Viktor Dvoryashin, 27, artist

Vladimir Galanov, 29, poet

Grigory Nikitin, 30, poet

Alexander Kudryavtsev, 39, typesetter

Alexander Poteryakhin, 32, writer

Mikhail Krotkov, 44, lawyer

Sergei Golovin, 58, doctor

Boris Glubokovsky, 30, theatre director

Ivan Kolobov, 37, profession unknown

Timofei Sakhno, 31, doctor

Sergei Yesenin and Alexei Ganin as young men

They were held in a cell of the Butyrskaya Prison. Sergei had sobered up. He asked Alexei if he had any idea why they had been arrested.

‘Maybe,’ Ganin said. ‘In your case, I’d say it’s pretty simple. You’ve been abroad. Abroad is full of enemies. If you’ve been there, you must have been consorting with them. And the fact that you’ve been writing such anti-Soviet poetry, well QED.’

‘God Almighty, Alex! That is such horse shit!’

Sergei was exasperated and frightened. He knew that Soviet prisons were full of informers.

‘Sure I went abroad,’ he said loudly. ‘But I spent the whole time defending the revolution and attacking the émigré scumbags. Didn’t you read the newspapers? I sang the Internationale. I picked fights with White officers. I insulted Merezhkovsky and the other lousy traitors.’

Ganin laughed. ‘OK, Seryozha. That’s your defence. I’d say you have a better chance than most of us of getting out of here. As for me and the others, I’m not so sure.’

‘What do you mean?’ Sergei looked horrified.

‘The trouble is that not all of us are prepared to let the Bolsheviks rape and pillage the Russia we love. Some of us have been standing up for what we believe in. You probably haven’t read anything I’ve written, but I wrote a novel called Tomorrow. It was all in code, of course, but it’s a real indictment of the bastards who’ve brought Russia to her knees.’

‘A novel! For Christ’s sake! They can’t lock you up for a novel!’

Ganin looked at him.

‘Where have you been, Seryozha? They can lock you up for anything nowadays. Anyway, the novel isn’t the whole of it. I’ve been working with a bunch of other guys – patriots, Russian nationalists; we all hate the Bolsheviks. We decided we had to offer an alternative to the dead-end the communists are taking us down. We wrote a couple of pamphlets; a manifesto, really. It’s called “Theses for Russian National Rebirth” and it really gives the lie to Lenin and Stalin and co. Well, it seems they got wind of it and they’ve been arresting us all, one by one. They’ve been charging us with belonging to some stupid organisation they’ve invented themselves, called the Order of Russian Fascists. As if we’d use such an idiotic title. It doesn’t matter what the truth is, though; if they want to crush you, they’ll do it.’

Zinaida helped Meyerhold unpack his bags. He could not contain his joy at seeing her. He was so lucky to have her as his wife.

He had booked a table for a celebratory dinner in the Grand Hall of the Metropol Hotel. When they arrived, the Maître D showed them to their table and invited Zinaida to be seated. He apologised to her, said he would need to borrow her husband for a few moments and led Meyerhold through a mirrored door into a side room.

Meyerhold came back twenty minutes later with two bottles of vintage Georgian wine. He was flustered.

‘A present from Josef Vissarionovich,’ he said. ‘From Stalin. He’s in the private room with Molotov and Kalinin. He wanted to say how much he admires our work. But he says we need to make our heroes more heroic – Onegin, Chatsky, Pechorin – they all need to be heroes. It’s madness, of course. But I was terrified. I just said fine, and agreed with him. I need a drink!’

They ate. They drank a bottle of Stalin’s wine. Meyerhold regained his composure.

‘Thank God I have you, Zina,’ he said. ‘God knows what I’d do without you. We must make sure we are never parted as we were these last months.’

Some of the other prisoners in the cell, long-term residents, spent the days arguing. It made the time pass. The arguments were heated. But there was a tacit convention that violence would not be used and grudges would not be borne.

Conversation turned to a discussion of the worst things about being in jail. The sound of rats scurrying around in the night topped the poll. Then the maggots in the food, the endless diarrhoea and vomiting, the shared lavatory pail. One man said the worst thing was the waiting, but a voice from a bunk in the corner said, ‘You won’t say that when you discover what you’ve been waiting for. Once the interrogators are beating your face to a pulp, you’ll be wishing you could be back here, waiting forever.’

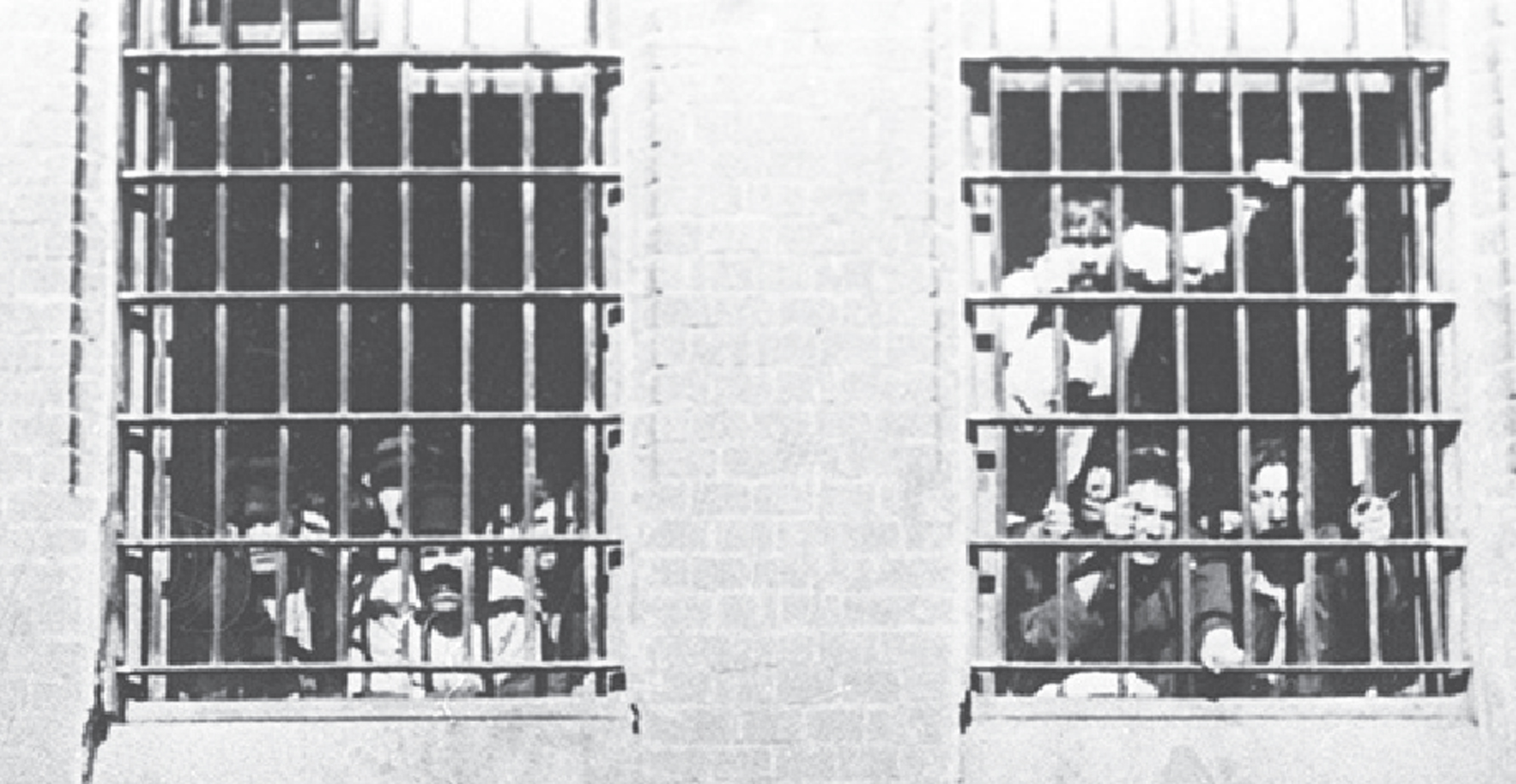

Butyrskaya Prison

The Order of Fascists was clearly a tricky case, the investigations long and complex. By the time the suspects were called for interrogation, their nerves were frayed.

Alexei Ganin went first. On 2 November 1924, he came before Senior OGPU Investigator Abram Slavatinsky. Slavatinsky produced documents that he said were found in the pocket of Ganin’s raincoat at the time of his arrest. They were vile tracts, full of anti-Bolshevik, anti-Russian propaganda. There was a nasty streak of Fascism and anti-Semitism in them. Slavatinsky threw them on the table with an air of triumph.

Ganin looked at the documents and shook his head; he had never seen them before.

Slavatinsky made a sign with his hand and two guards stepped forward. One pinned Ganin’s arms behind his back, while the other punched him repeatedly in the face.

‘That’s what they all say,’ Slavatinsky said. ‘They all deny the truth – at first. None of them keeps it up for long.’

Sergei was released without explanation. He was woken by a guard and told to collect his possessions from the desk. There was no time to say goodbye to Ganin or anyone else.

Back in the flat on Afanasievsky Lane, he scoured the newspapers. He could find no reference anywhere to Alexei Ganin and no mention of any organisation by the name of the Order of Russian Fascists.

A single news item on an inside page of Evening Moscow stated that the poet Sergei Yesenin had again been arrested – charges unknown – and subsequently released. There was a quote from Vladimir Mayakovsky to the effect that Yesenin was now appearing more frequently in newspaper crime columns than in poetry.

Sergei went looking for Zinaida. He had hoped she would be waiting for him at the flat. His unexplained disappearance and the lack of news about him must have alarmed her. He needed to find her and tell her he was safe.

He went to Shershenevich, who was relieved to see him. But no, he had heard nothing from Zinaida.

Zinaida was finding life in Bryusov Lane stressful. She felt guilty about breaking her promise to Sergei, sure he must have taken it badly. The fact that he hadn’t come looking for her must mean he had started drinking again. He was probably lying in some gutter. She wanted to go and look for him, but she knew that would make things unbearably complicated. The longer Sergei didn’t come, the more she felt she had made the right decision. Meyerhold seemed oblivious. He was his usual, dependable self. He had commissioned a new portrait of her that he hung in his study and showed to everyone who came to see them.

Sergei never learned what had happened to his best man. The facts of the Alexei Ganin case would emerge only when the files of the Soviet secret police were opened after the collapse of the USSR in 1991.

According to OGPU records, Senior Investigator Slavatinsky had concluded on the basis of the available evidence, supported by a full and detailed confession voluntarily given by the accused, that all the alleged members of the Order of Russian Fascists were guilty as charged.

Slavatinsky had communicated his findings to the OGPU Director, Felix Dzerzhinsky and his deputy, Genrikh Yagoda, who may well have been amused. The Order of Russian Fascists and other similar organisations, such as the Monarchist Union of Central Russia and the Underground Trust, were inventions of Yagoda’s imagination. They were fictions, used by the OGPU to frame suspects whose views they didn’t like.

On 25 March 1925, the Secretary of the Central Committee, Avel Yenukidze, signed an order granting the OGPU the right to deal with ‘the fascists’ as it saw fit, with no need for a trial.

For Alexei Ganin, both of the Chekrygin brothers, Viktor Dvoryashin, Vladimir Galanov and Mikhail Krotkov, the sentence was death. The others were given jail terms of between ten and twenty years.

Ganin would be shot on 30 March 1925, his saint’s day, in the Butyrskaya Prison, together with the other young poets from the list. Their bodies were transported to the mortuary of the Yauzskaya Clinic in central Moscow, to be buried in the hospital’s wooded grounds. When the OGPU records were opened seven decades later, there were more than a thousand requests between the years of 1920 and 1926 for the disposal of executed prisoners there.

The drama of the autumn had damaged Zinaida’s fragile psyche. She spent the winter filling her diary with pages of scrawled reflections. She wrote of the damage she had caused, of her regret for the love she had given up, of her dissatisfaction with the safety and comfort she had chosen. She feared she was turning into a character from Chekhov. She had played so many of his roles, absorbed so many of his lines that they swirled in her head and gave her no peace.

I married the Latin professor, who declines amo, amas, amat, but doesn’t know what it means . . . My heart is a grand piano that can’t be used because it’s locked and the key is lost.

Sergei and I love each other. That’s what matters . . .

It isn’t all that matters.

Other things matter, too. Self-respect matters, and decency.

I can’t go on . . .

Who will remember us when we are dead? We forget the sacrifices of previous generations and the future will forget ours . . . What seems to us now to be so serious and important will be forgotten.

But can we really say goodbye? Never see each other again?

The strain of our different lives, our lives apart from each other.

The feeling of guilt. Too great a price to pay. I shall love him until the end of my life.

I know he feels all this. It is the same for him.

Too cruel. We can’t do such violence to our hearts.

I must talk to him.

It’s torturing me . . . the decision I made.

I remember our last day together. We went from the flat and walked as far as Tverskaya. I lit cigarettes for him. We didn’t talk much. We walked the same streets that we’d walked so many times before.

I shall see all this again, but without him . . . without Sergei.

Meyerhold was at the door of her room. She closed her diary and hid it under a book. She felt she was committing some act of treachery towards him.

‘Vsevolod,’ she said. ‘I don’t know what is happening to me. I feel so distracted. I can’t remember the simplest things any more; others keep crowding into my brain and pushing them out.’

Meyerhold put his arm around her.

‘What is it? What is it, darling?’

‘Where? Where has it all gone? I’ve forgotten everything . . . everything’s in a tangle . . . I don’t remember the Italian for window or ceiling . . . Every day I forget something more. Life is slipping away and will never come back.’

‘Darling, darling . . .’

‘I’m so sad! I’ve had enough of it! My brain is drying up; I’m getting fat and old and ugly, and there’s nothing, nothing, not the slightest satisfaction. And time is passing and it just feels as if we are moving away from a real, beautiful life, moving farther and farther away and being drawn into the depths. I’m in despair. I don’t know how it is that I’m alive and haven’t killed myself . . .’

‘Don’t cry, my child, don’t cry. It makes me miserable.’

‘I’m not crying. I’m not crying . . . It’s over . . . There, I’m not crying now. I won’t . . . I won’t . . . I see that we shall never, never go to Moscow! I see that we won’t go!’

Nobody told Sergei why he was released. The authorities rarely explained. Terror was reinforced by uncertainty. So, in the same way, relatives of executed prisoners would be informed that their loved ones had been sent to the Gulag ‘without the right to correspondence’. In those early years, the phrase was a new one and many clung to the hope it offered.

Most likely, they released Yesenin because he was famous and Ganin was not; because his poems were cherished by millions who had never heard of Alexei Ganin; and because Ganin had written his contempt for the regime in a pamphlet rather than just poetry.

It didn’t take Sergei long to discover that Zinaida was with Meyerhold. Late at night, drunk and impetuous, he banged at their door. The building was asleep.

‘Give me my wife back! You have my wife and my children! Give them back to me!’

The neighbours appeared and warned him to leave. Next time they would call the police.

When he came back the following evening, they did. Sergei spent the night in a cell.