It is five o’clock in the morning and the clear indigo sky glistens with an archway of stars. On the distant horizon the pre-dawn light eats away at the night and heralds the return of the sun on the day of the spring equinox – a time of equal light and darkness and the midway point between the winter and summer solstices.

Towards the north-west is the diffuse yellow glow thrown up by the lights of modern-day Cairo – its daily hustle and bustle and street chaos not yet begun – but before us, on the edge of the Giza plateau, is arguably the most enigmatic carved monument in the world. It is a graceful leonine form with the face of a Pharaoh, a body of stone and a battered tail that curls around its hunched-up hind legs. Its extended fore legs reach out towards the eastern horizon as if to emphasise its integral relationship with the coming equinoctial sunrise. The world knows this monument as the Great Sphinx. It wears the same nemes head-dress as the dynastic kings that ruled the peoples of Egypt for over 3000 years.

Those academics who dedicate their lives and careers to studying the world behind such monuments tell us that the Sphinx was carved from an outcrop of bedrock by a school of dedicated stone sculptors during Old Kingdom times, the epoch of the pyramid builders. This great act had necessitated the hollowing out of a huge wedge-like enclosure, after which the fashioning of the enormous recumbent lion had taken place. A stone crown was then placed on its head, a beard was inserted into its chin and the face was chiselled into the likeness of a king named Khafre, who took the throne of Egypt in around 2550 BC.1

Yet those Egyptologists who have made such strong assertions concerning the origins of the Sphinx are almost certainly wrong. As we move around the edge of its sunken enclosure, the ground-lights silhouette deep undulating grooves running around the monument’s badly eroded body. They are curved and smooth and seem to have been caused by severe weathering over an enormously long period of time, even though the Sphinx is known to have been buried up to its neck in sand for at least 3300 years of its official 4500-year history.2 Here and there the deep horizontal scars are broken by sharp vertical fissures – they are plainly visible all around the Sphinx and are also present on the interior walls of the Sphinx enclosure.

The Egyptologists tell us that these weathering effects were caused by the harsh desert winds that blow in from the south and engulf the leonine form in an elemental maelstrom. It is what they have always believed, and probably always will. Yet these people are not geologists; they do not study the composition and erosion of rocks. This is a pity, for geologists say something completely different about the poor condition of the Sphinx and its surrounding enclosure. They say that the deep horizontal scars and sharp vertical fissures were caused not by the desert sands but by water precipitation – in other words, rain. Lots of it, over a very, very long period of time. One geologist, Dr Robert Schoch, an Associate Professor of Science at Boston University,3 has argued in favour of this proposition again and again in more radical periodicals and journals, such as KMT, America’s prestigious news-stand magazine on speculative Egyptology.4 Repeatedly, Schoch and his colleagues have demolished any criticism raised against their water precipitation theory, so much so that the Egyptologists are going to have to come up with something pretty convincing before any open-minded individual is going to take their argument seriously any more.

So the weathering on the Sphinx and the walls of its surrounding enclosure was caused by exposure to rain over an extremely long period of time, but just how long? Egypt has seen very litde rain since the age of the Pharaohs began over 5000 years ago. Indeed, to find a time in climatological history when rain of this order fell on Egypt we must go back to the 3500-year stretch between 8000 and 4500 BC, when the Eastern Sahara was a green savannah periodically drenched by perpetual downpours of the sort familiar to more tropical climates.

Torrents of water running down the Sphinx’s carved limestone body and surrounding enclosure walls over a period of many thousands of years would have resulted in the deep horizontal scars and vertical fissures seen today. Yet no Pharaohs lived between 8000 and 4500 BC, and from what we know of archaeology in Egypt there doesn’t appear to have been much happening at all at around this time. The only signs of life are primitive farming communities, either in what became the eastern Sahara or on the banks of the Nile, where they could take advantage of the abundance of fresh fish. Yet these early, so-called neolithic communities did not possess a structured society and are not known to have carved colossal stone monuments such as the Great Sphinx. What’s more, they did not have the technology or the impetus to engage themselves in such massive engineering projects, even if we could find a suitable reason why they should have wanted to fashion themselves a colossal lion in stone.

So if these early farming communities did not carve the Sphinx, then who did?

Perhaps we are looking at the wrong time-frame altogether, and the Sphinx was carved during an entirely different age. If so, when?

IN THE AGE OF THE LION

On the eastern horizon the dull red light of the equinoctial sunrise reaches higher into the dark firmament. As star after star gives way to the light, others seem defiant, their flickering glow watched carefully by the eyes of the Sphinx. Picked out clearly on the eastern horizon are the uppermost stars of the constellation known to the Western world as Pisces. Above, and a little to its right, is the constellation of Aquarius. Like its celestial neighbour, Aquarius is one of the twelve signs of the zodiac – the chain of constellations through which the sun is seen to pass on its yearly course across the starry firmament. Each month the sign in which the sun rises changes, defining the yearly zodiac originally used in astrology to cast horoscopes.

There is, however, another zodiacal cycle that takes not a single year to complete its cycle but a mammoth 25,920 years.5 Known as precession, or backwards motion, it is caused by the slow wobble of the earth – which if dramatically speeded up and viewed from the moon would look like the gentle sway of a child’s spinning top. Its progress can be measured by the gradual shift of the starry canopy in relation to the distant horizon at a rate of one degree every seventy-two years.

The precessional cycle was equated by the Ancients with the so-called Great Year, as well as the supposed ages of man defined by classical writers such as Hesiod (fl. 850 BC). In astronomical terms its steady progress at a snail’s pace is registered by noting the zodiac constellation that appears in the path of the sun just before sunrise on the spring equinox. Every 2160 years or so the sign changes, and when it does a new astrological age is born.

Today we are poised on the brink of the Age of Aquarius as the stars of Pisces, a symbol of Christianity for the past 2000 years, set below the equinoctial horizon for the final time; this will occur gradually over the next 200 or so years.6 Yet before the advent of the Age of Pisces, the world was ruled by the Age of Aries, the ram, the symbol of the faith of Abraham and the cult of Amun in Ancient Egypt, which both rose to prominence some time after the commencement of this epoch, c. 2200 BC.7 As the ruler of the precessional year, the ram had itself replaced the previous Age of Taurus, whose bull cult had dominated the Mediterranean and still lingers today in the barbaric bullfights acted out in the great stadiums of Spain.

Had the Great Sphinx been carved when the Egyptologists insist in around 2550 BC, i.e. during the Age of Taurus, then surely it would make better sense for it to have been modelled into the statue of an enormous bull. Each year before dawn on the spring equinox it could have gazed out at its celestial counterpart in the starry sky. Ancient cultures of the Middle East are known to have venerated, and even depicted in religious art, the equinoctial rising of Taurus during this precessional age.8 Moreover, the bull was worshipped in Egypt’s chief city of Memphis during this distant epoch under the name of Apis. Ancient paintings depict it with the solar disc between its horns, confirming its allegiance to the sun and making it an ideal equinoctial time-marker during the much-celebrated Taurean age.

Yet as we can clearly see, the Sphinx is not a bull at all but a lion, and the lion is the symbol of Leo. So when might the last Age of Leo have taken place? Computer software allows us to punch coordinates and dates into a keyboard and then watch as the sky in an age witnessed only by our most distant ancestors is displayed on a monitor screen. It makes calculations easy, and tells us that before the Age of Taurus there had been an Age of Gemini, an Age of Cancer and, prior to that, an Age of Leo, which occurred during the 2160-year period between c. 11,380 and 9220 BC (see Chapter Three).

Only in this distant epoch would the construction of a lion as an equinoctial marker have made complete sense, for only during this distant epoch would it have gazed out at its starry counterpart before sunrise on the spring equinox. If so, then originally the Sphinx may well have borne not the face of a Pharaoh but the head of a lion. Then, at a much later date, plausibly during the rein of Khafre in around 2550 BC, its head was remodelled into the likeness of a king bearing the more familiar nemes head-dress.

Such hasty assumptions might at first seem nonsensical if not a little rash. Yet there is ample evidence that the Ancient Egyptians not only understood the slow process of precession9 but that they were also obsessed by great cycles of time stretching back over tens of thousands of years. For instance, the fragmented Royal Canon of Turin, dating to the Nineteenth Dynasty, c. 1300 BC, contains a list of kings that includes a long period when a succession of 10 netjeru (or nṯrw), a word meaning ‘divinities’ or ‘gods’, ruled the world. Their reigns are followed by a further period of 13,420 years when divine beings known as Shemsu-hor, interpreted as the ‘Companions’ or ‘Followers of Horus’, are said to have governed the country prior to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in around 3100 BC.10 In addition to this, Manetho, a priest of the city of Heliopolis who lived c. 320 BC, spoke of a period of 24,925 years before the ascent of Menes, the first dynastic king,11 while Herodotus, a Greek historian of the fifth century BC, observed in his Canon of the Kings that 11,340 years had passed since the rule of the first Pharaoh.12

The Ancient Egyptians also spoke of a mythical epoch known as sep tepi, the First Time, seen as a kind of golden age when their land was ruled by the netjeru, such as Osiris and his son Horus. It was looked on by them as a time of ‘absolute perfection – “before rage or clamour or strife or uproar had come about”. No death, disease or disaster occurred in this blissful age, variously described as “the time of Re”, “the time of Osiris”, or “the time of Horus”.’13

That the Sphinx acted as a time-marker for the Age of Leo is becoming more widely accepted as the world enters the new millennium. A date of construction some time around 10,500 BC has been discussed openly in the pages of many best-selling books written by forward-thinking authors who are challenging orthodoxy head-on. Individuals such as construction engineer Robert Bauval and speculative writer Graham Hancock argue admirably that a mirror image of the starry heavens, as they might have appeared to a person on the ground during the Age of Leo, is reflected in the positioning and orientation of the monuments found on the Giza plateau.14

These people are now at loggerheads with the academics, who not only say their theories are new-age nonsense but claim that in the time-frame suggested, the eleventh and tenth millennia BC, the Eastern Sahara was inhabited only by ‘bands of people who lived in small huts or shelters and sustained themselves by hunting and gathering’.15 They also state that these early Nilotic (i.e. those living by the Nile) communities ‘erected no large stone structures of any kind’ and had not ‘taken even the first steps towards the domestication of plants and animals’.16

This is simply not true. There is much evidence of prehistoric man along the Nile during this very age, and it clearly shows that between c. 12,500 and 9500 BC certain communities not only possessed an advanced tool-making technology but also domesticated animals and developed the earliest agriculture anywhere in the world17 (see Chapter Fifteen). Moreover, just 483 kilometres (300 miles) away from Giza in what is today Jericho, its inhabitants of c. 8000 BC were constructing enormous fortification walls, gouging out vast trenches in the hard bedrock and erecting a gigantic stone tower in defence against an unknown enemy.18 Engineering projects on this scale would have required a high level of social structure and coordinated operations.

This much is known; there is almost certainly more. No one can say that humanity in this distant age did not have the ability to carve the image of a 73-metre-long recumbent lion, and yet accepting this hypothesis brings with it an even greater mystery.

TEMPLES OF THE GODS

The pre-dawn light increases, allowing the eye to pick out the dark shapes of architectural ruins in varying degrees of preservation and decay. Beyond the eastern exit of the sunken Sphinx enclosure are the remains of a quite extraordinary structure known as the Valley Temple of Khafre, which, like the Sphinx itself, is orientated east towards the equinoctial sunrise. It is constructed of enormous limestone blocks – many up to 100 tonnes in weight, some as heavy as 200 tonnes – on a square ground-plan close to the edge of the 40-metre-high Giza plateau. Each side is 45 metres in length, while its unusual foundation on a gradual slope means that the height of its walls varies considerably. Its eastern wall soars to over 13 metres, while its western counterpart rises to just 6 metres. Enormous limestone facing-blocks once lined its exterior walls, while inside ashlars of dark red granite and a paved floor of pure alabaster are to be found. The interior of the temple is shaped like a letter T, defined by a rigid network of rectangular pillars, or monoliths, 5.5 metres high, each capped with granite beams laid horizontally on them. Nowhere will you find any inscribed hieroglyphs or stone reliefs, and yet the effect is still one of great perfection and immense magnitude.

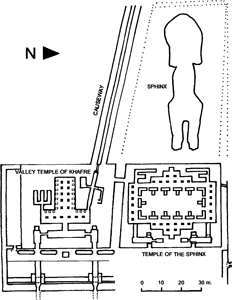

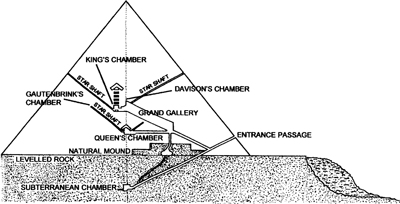

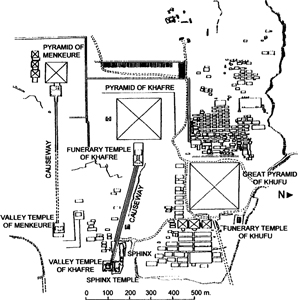

Plan of the Sphinx monument, the Temple of the Sphinx and the Valley Temple of Khafre.

Egyptologists assert that the Valley Temple was built at the time of Khafre, c. 2550–2525 BC. Certainly, it is linked via a stone causeway to another ancient temple on the eastern side of the Second Pyramid, the middle one of the three at Giza, which is also accredited to Khafre. Further evidence of this conclusion, they say, is the Valley Temple’s similarity in design to other temples on the Giza plateau, as well as its proximity to the Great Sphinx and the fact that statues of Khafre – one depicting him in the form of a reclining sphinx and another in diorite showing him seated – were found abandoned in a well located beneath its floor.19

Pretty strong evidence, you may think, in favour of Khafre’s association with Giza’s curious cyclopean or megalithic (i.e. great stone) structure. Yet there the connections cease, for it is known that the colossal limestone blocks used in the construction of both the Valley Temple and the adjacent Temple of the Sphinx, of which only the foundations remain today, were extracted from the Sphinx enclosure, which began its life as a quarry.20 This is a slightly disconcerting prospect, for if the Sphinx really was constructed prior to the end of the Age of Leo, c. 9220 BC, then it implies that the nearby temples must also date back to this same distant epoch.

Confirmation that the Valley Temple predates Pharaonic times is easy, for the same weathering effects found both on the body of the Sphinx and on the surrounding enclosure are also clearly visible on its core walls. More important, the worst of these smooth, undulating scars caused, we can only assume, by water precipitation over the period between c. 8000 and 5000 BC were shaved away during Old Kingdom times, c. 2700–2137 BC – plausibly during the reign of Khafre – to allow the granite ashlars to sit flush against the rough limestone walls. If this really is what happened, then it is damning evidence against the orthodox view that ascribes the weather-worn limestone shell of the Valley Temple to the age of the Pharaohs.

Not unnaturally, the Egyptological community would never entertain the idea that the Valley Temple might be older than Old Kingdom times. Yet when the Temple of the Sphinx, or the Granite Temple as it was formally known, was uncovered for the first time by French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette (1821–81) in 1853, scholars were more than happy to admit that its cyclopean masonry and complete lack of hieroglyphic inscriptions confirmed its immense antiquity. Mariette even believed it to be the oldest structure ever uncovered in Egypt.21

Such a colossal style of building is not unique to the Valley Temple. As previously mentioned, the nearby Sphinx Temple also contains huge cyclopean stones, while the ruins of the so-called Upper Temple, situated east of the Second Pyramid and linked to the Valley Temple by a stone causeway, are made up of similarly sized blocks, one of which is estimated to be an unbelievable 468 tonnes in weight.22 Furthermore, 434 kilometres (270 miles) south of Giza at the predynastic cult centre of Abydos is another megalithic temple of unknown origin. Known as the Osireion, it contains enormous granite posts capped with huge stone lintels. Set within its interior walls is a series of 17 cells, or cubicles, plausibly used for some kind of sacred function. Below this more-or-less subterranean structure is a well that floods to surround a purposely built plateau of cut stone slabs, creating the impression of an island surrounded by water. Although the building is attached through orientation and locality to a nearby temple built during the reign of King Seti I (1307–1291 BC), no one has ever been able accurately to date the Osireion.

Professor Edouard Naville of the Egypt Exploration Fund, who worked extensively on the Osireion between 1912 and 1914, compared the structure’s unique architecture with the Valley Temple, showing it to be ‘of the same epoch when building was made with enormous stones without any ornament’.23 Such observations led him to conclude that the Osireion, ‘being of a similar composition, but of much larger materials, is of a still more archaic character, and I would not be surprised if this were the most ancient architectural structure in Egypt’.24

The Egyptological community dismissed Edouard Naville’s earlier findings, following the discovery by Henry Frankfurt – who excavated at the site between 1925 and 1930 – of a cartouche bearing Seti I on a granite dovetail by the main entrance into the central hall, as well as one or two other simple finds that linked the Pharaoh’s reign to the building.25 As a consequence, the building was henceforth seen as contemporary to Seti’s reign.

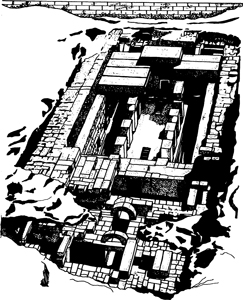

View of the Osireion at Abydos.

That the enlightened King Seti might have constructed his own temple complex at Abydos to comply with the existing orientation and ground-plan of the Osireion, which was already of immense antiquity even in his own age, is never considered by the Egyptological community. Yet in the opinion of myself and many others working in this field today, it is far more likely that the Osireion, like the Valley Temple and many of the other cyclopean structures of Giza, is a surviving example of megalithic architecture dating to a much earlier epoch altogether.

A LEGACY FOR FUTURE TIMES

As the pale light of the equinoctial sunrise steadily increases, it lifts the veil of darkness covering the elevated plateau. It picks out the presence of Giza’s most awesome legacies of the past – the three great pyramids that tower skywards like immortal sentinels marking the achievements of an unknown age we can only just begin to comprehend.

Two and a half million blocks, ranging in size from two to seventy tonnes apiece, were used in the construction of the Great Pyramid, the largest and perhaps the most enigmatic of the three matching structures. It covers an area of five hectares and weighs an incredible six million tonnes,26 and until the construction of the Eiffel Tower it was the tallest structure in the world. There is more stone in the Great Pyramid than in all the churches, chapels and cathedrals built in England since the time of Christ.27 Yet this great wonder of the past is more than simply an architectural curiosity, for it embodies a level of sophistication far superior to anything the world has produced in any epoch since. Over the past 200 years many hundreds of books have been written about the mysteries of the Great Pyramid, most of them more fantasy than fact. Yet shining through all of them is a hard core of evidence which really does show that the pyramid builders were privy to universal knowledge far beyond that accredited to the Ancient Egyptians by scholars today. It would be laborious to detail each and every one of the amazing facts attributed to this monument in stone, but I feel it is essential to convey just a little of the extraordinarily advanced minds behind this architectural wonder.

To begin with, its four sides, which average 230.36 metres in length,28 are aligned to the four cardinal points with such precision that engineers today would find difficulty in matching such accuracy.

More remarkable is our knowledge concerning the perimeter of the Great Pyramid. It is said to be 921.453 metres, which, according to modern calculations by noted metrologist Livio Stecchini, is exactly equal to a half a minute of latitude at the equator, or 1/43,200 of the earth’s circumference.29 A revelation such as this might seem fantastic, and yet it is a fact that the Ancient Greeks were dimly aware of the pyramid’s apparent relationship to the earth’s latitude in their own day and age, which is why Napoleon’s savants were ordered to survey the monument when the French army entered Egypt in 1798.30 Most people believe that the concept of latitude and longitude as the geographical basis for mapping out the earth is a relatively modern invention, but if such information is encoded in the design of the Great Pyramid then the world is going to have to think again. Indeed, Stecchini has ably demonstrated that the Ancient Egyptians had already defined the extent of their country in relationship to the earth’s latitude and longitude when the first Pharaoh took the throne in around 3100 BC.31

Another similar mind-boggling fact concerns the height of the Great Pyramid. The ancient mysteries writer, William Fix, calculated that from the base of its 54.6-centimetre-thick foundation platform to the tip of its apex is just over 147.14 metres. This, when multiplied by 43,200 – the same number used in achieving a half a minute of latitude in respect to the structure’s perimeter – produces a figure just 120 metres short of the polar radius of the earth, or the distance from the centre of the earth to the North Pole.32

Look up now at the pyramid’s distant apex – which is closer to heaven than the roof of a 40-storey building. Its actual height, from the lowest to the highest course, is 146.59 metres, and if you divide the perimeter by twice the height you achieve a figure that corresponds to the true value of pi, 3.1416.33 The Great Pyramid therefore embodies within its geodesic form an exact model of the earth’s northern hemisphere on a scale of 1:43,200.34

And the data continues. The Great Pyramid stands at the precise centre of the earth’s largest landmass, while its north-western and north-eastern diagonals seem to define the triangular shape of the Nile tributaries that make up the Nile Delta.35 If these waterways trace the same courses as they did in the pyramid age, then this suggests some kind of symbolic relationship between the orientation of the Great Pyramid and the actual landscape of Lower (or northern) Egypt.

Egyptologists do not deny such facts; they see them simply as pure coincidence and nothing more. In their minds the Ancient Egyptians were certainly not aware of the earth’s diameter, so they could not possibly have encoded such information into the design of any man-made construction. Such statements are wholly unacceptable and just seem to show the utter stubbornness adopted by many academics. Are we simply to accept their opinion of the past, which more or less implies that ancient man was not capable of understanding such advanced scientific principles?

The Great Pyramid is undoubtedly a highly unique artefact of history, but it is not just its exterior design that preserves remarkable geometric precision. The King’s Chamber, the bare, granite-lined room placed high in the pyramid, is seen by Egyptologists as the burial chamber of a Pharaoh because it contains a lidless box in dark granite, described variously as a coffer or sarcophagus. Yet looking closely at the measurements of this chamber, we find that its dimensions embody geometry that preserves both the 2:√5:3 and 3:4:5 triangles supposedly devised by Pythagoras, the famous Greek mathematician of the sixth century BC.36 These observations were made originally not by some loose-minded pyramidologist but by the much-respected Egyptologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853–1942), who conducted an exhaustive survey of the pyramids and temples of Giza in 1881 (see Chapter Four).

Cross section of the Great Pyramid.

Could Egypt have been the birthplace of geometry, as the ancient writers such as Diodorus Siculus, Herodotus and Plato would appear to have believed?37 And from geometry we go to metrology, the science of weights and measures. It is a fact that the internal volume of the King’s Chamber coffer, calculated at 1166.4 litres, is precisely half the volume defined by its exterior measurements, which gives a figure of 2332.8 litres.38

I could go on. The list of strange facts concerning the Great Pyramid is endless. None of this is likely to be coincidence, as the academics would have us believe. It seems more credible to suggest that the pyramid builders purposely created a legacy for future times. Through the universal languages of science, mathematics and engineering, they were attempting to put on record their vastly superior knowledge and wisdom of geodesy, geometry, metrology and harmonic proportions.

We can only marvel at these people’s achievements, for they beg the question of exactly where this universal knowledge and wisdom came from, or, indeed, just who did build the Great Pyramid. Egyptologists tell us it was constructed as the tomb of a Pharaoh. With the flimsiest of evidence they tell us it was commissioned by a king named Khufu (the Greek Cheops) early in the Fourth Dynasty, c. 2596–2573 BC.39 They also tell us that the Second Pyramid was made for a king named Khafre (or Chephren), c. 2550–2525 BC, while the Third Pyramid was constructed for Khafre’s successor, Menkaure (or Mycerinos), who ruled c. 2512–2484 BC.

In the absence of hardcore evidence to suggest otherwise, no one can say that Khufu, Khafre and Menkaure were not in some manner connected with the construction of the three pyramids. There is too much evidence to show that the Giza necropolis owes its existence to this dynasty, which is placed in the era of Egyptian history known as the Old Kingdom, c. 2700–2137 BC. What can be doubted is how exactly the designers of the Great Pyramid obtained their vast technological capabilities in the 500 or so years from the ascent of the first Pharaoh of a unified Upper and Lower Egypt in around 3100 BC.

Plan of the Giza plateau.

The presence alone of the Great Pyramid tells us that the Ancient Egyptians were no fools. Nothing seems to have been left to coincidence or chance. This monument was built to tell us a story of their past, and that past indicates strongly that they were the inheritors of a universal knowledge and wisdom that was the culmination of many thousands of years of evolution and progress in understanding the ways of this world.

If this is true, then the Great Pyramid’s proximity to the Sphinx and its accompanying megalithic temples is also no coincidence. There is a clear message here, and if it could be put into plain language then it would probably read as follows:

What we have embodied in stone and you have now understood is an expression, a celebration, of that which was handed down to us by those who established the sanctity of this elevated plateau during the First Time, the age of the gods. Let this be a monument to their memory.

Mere fiction? To many it might seem so, but ancient sources speak openly of the great knowledge and wisdom preserved in the design of the Great Pyramid. For instance, the so-called Akbar Ezzeman manuscript, attributed to the tenth-century Arab traveller named al-Mas’ūdi and based on a now-lost Coptic historical work (see Chapter Three), says it contains:

. . . the wisdom and acquirements in the different arts and sciences . . . [as well as] the sciences of arithmetic and geometry, that they might remain as records for the benefit of those who could afterwards comprehend them . . . [it also preserves] the positions of the stars and their cycles; together with the history and chronicle of time past [and] of that which is to come.40

In my opinion there is compelling evidence to suggest that the Ancient Egyptians inherited their great wisdom from a much earlier Elder culture which was able to pass on the flame of knowledge before its own apparent demise. As we will see, all the indications are that the Elder gods inhabited Egypt some time between c. 12,500 and 9500 BC. They built the Sphinx and the earliest megalithic temples of Giza, and they achieved a high level of sophistication later encapsulated in the design of the Great Pyramid. Of this we can be fairly sure, but what else might they have left to the world?

SECRETS UNDERGROUND

As we enter the next millennium, many great discoveries are being made on the Giza plateau. None of these can be more extraordinary than the detection beneath the Sphinx’s wedge-shaped enclosure of a series of nine concealed chambers of unnatural origin. These were first detected by seismic soundings of the hard bedrock during two tentative search programmes, one led by seismologist Thomas Dobecki in 1991 and the other coordinated in 1996 by the University of Florida in association with the Schor Foundation41 (see Chapter Twelve).

Myths and legends that date back to Pharaonic times speak of a subterranean world lying beneath the Giza plateau. Modern-day psychics, occult societies and new-age mystics all firmly believe in the existence of an underground complex of concealed corridors and unknown chambers. They refer to this chthonic, or underworld, domain as the ‘Hall of Records’, or the ‘Chambers of Initiation’, and say it contains the arcane wisdom and knowledge hidden from the world by Egypt’s Elder culture.

Once again, ancient sources appear to support such bold assertions. For example, the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus (fl. AD 360–90) spoke of the pyramids of Egypt before adding that

There are also [in their vicinity] subterranean fissures and winding passages called syringes, which, it is said, those acquainted with the ancient rites, since they had fore knowledge that a deluge was coming, and feared that the memory of the ceremonies might be destroyed, dug in the earth in many places with great labour . . ,42

What exactly were these ‘ancient rites’ that needed to be preserved from being lost in ‘a deluge’? What on earth lay beneath the Great Sphinx? Might the revelations contained in these mysterious ‘syringes’ be connected with the previously unknown chambers found by sensitive scanning equipment during the 1990s? Have the geophysicists working on these projects really registered the echoes of Elder gods whose collective memory still lies slumbering beneath the limestone bedrock of the Giza plateau?

With the weathered eyes of the Sphinx fixed on the orange solar orb that now rests like a ball of liquid fire on the eastern horizon, a sense of great expectancy overwhelms me. As the world moves imperceptibly towards the precessional Age of Aquarius, it is as well to remember that, since the fall of the Age of Leo, the background canopy of stars has shifted almost 180 degrees against the distant horizon, or exactly one half of a precessional cycle. For the first time since this forgotten epoch of mankind, the stellar background will be a mirror reflection of how it might have appeared to those who built the Great Sphinx.43

Sensing its approach is like waiting for the alarm to sound on some imaginary celestial clock. What therefore is it timed to release? Is it the secrets concealed in darkness within the chambers beneath the Sphinx? If so, then it is important that we learn everything there is to know about the almost alien world of those who might have constructed them. We need to establish their identity, their effect on humanity, their ultimate fate and the extent of their technological achievements, for only then will we stand a chance of comprehending the Elder gods’ greatest legacy to mankind.