The remarkable cult buildings and carved monuments of the earliest neolithic sites of eastern Anatolia appear to resonate the same strange ambience as the stone structures of Egypt now accredited to the Elder gods. This much seems clear. Yet if we now turn our attentions to Nevali Çori’s enigmatic carved statues and compare them with the image conveyed of the divine inhabitants of Wetjeset-Neter in the Edfu Building Texts, then an even greater picture emerges. The Edfu account speaks repeatedly of falcons, or Sages, adorned with the wings and feathers of this bird of prey, suggesting perhaps that these individuals were men dressed as birds, or bird shamans. At Nevali Çori this is evidenced in the mysterious statues of birds and bird-men unearthed by Hauptmann and belonging to all three building phases of the cult house, from 8400 through to around 7600 BC.

According to Harald Hauptmann, the beautifully carved statue of a bird with enormous eyes and the head of a serpent, which he found Vailed up’ in a section of Building II, can be identified with the vulture.1 He was unwilling to place the same interpretation on any more of the bird carvings,2 although in my opinion the 23-centimetre-high standing figure of a bird-man, with large closed wings and stumps for arms, found face down within a walled recess in Building III, shows every sign of being a vulture. Its bizarre elongated head seems highly reminiscent of the long-necked vulture, and if this is indeed the case, then it seems likely that some, if not all, of the other bird-linked sculptures also depict men and women either dressed as vultures or wearing head-dresses made of vulture feathers.

If so, then what was so special about the vulture?

Vultures are creatures much reviled by the modern world. These enormous birds, many species with wingspans greater than 3.5 metres across, are carrion-eaters, in that they feast on the flesh of the dead. They will gorge on the carcasses of animals, birds or human beings, very often climbing inside the ribcage to tear out internal organs. Despite this highly repulsive activity, they are actually very clean birds and were gready revered in ancient times as symbols not only of mortality but also of death-trances and mental transformation induced by psychotropic drugs, sensory deprivation and near-death experiences (NDEs). By taking on the guise of the vulture, shamans and initiates were thought to be able to attain astral flight, enter otherworldly realms, communicate with ancestor spirits and bring back universal knowledge and wisdom.

The mighty vulture, once the primary symbol of death, transformation and rebirth throughout the neolithic world.

PICKING THE DEAD CLEAN

Of equal importance in the cult of the vulture was the bird’s role in the funerary practice known as excarnation, also called ‘sky burials’, where dead bodies would be exposed on high wooden platforms in charnel areas located well away from setdements. Carrion birds such as the vulture and the crow would then be allowed to feast on the human carcass until all that remained was a denuded skeleton – a process that would have taken as little as 30 minutes. The remaining bones would then be left to dry before being collected up and buried either in stone chambers or beneath the ground, often in the floor of the deceased’s relatives’ own home!

Very often excarnation would have involved what is known as fractional or secondary burial, whereby the bones would be separated out and concealed at more than one location. For instance, at many sites in the Near East, skulls would be removed from the skeleton and placed beneath the floors of buildings usually with some kind of cultic significance. Other skulls would be preserved, either by the deceased’s relatives or by shamanic priests, and used for oracular purposes, in other words communicating with the spirit of its former owner, which was believed to inhabit the skull, even in death.

Many skulls used for such purposes were first covered with mortar and given decorative eyes made from cowrie shells or shell fragments, as if to emphasise the embodied power and presence of their earthly owners. This form of ancestor worship was common throughout the neolithic period in many parts of the Near East.3 At Nevali Çori skulls were buried in pairs along with so-called long bones (human femurs), and many of these were positioned so that they faced each other.4 Evidence here of secondary burial also implies that excarnation took place; however, the skulls Hauptmann and his team unearthed do, in fact, date to a slightiy later period than the cult building.5

BIRDS TO MEN

A more spiritual dimension to the cult of the vulture was the belief that after death the bird would accompany the deceased into the next world as its guide, or psychopomp. This heavenly location was generally considered to be in the direction of the pole star, i.e. to the north, and once here the discarnate soul would be judged by the gods, following which it would either achieve immortality or wait in a limbo state for reincarnation.

Our knowledge of the significance of excarnation in ancient times derives mainly from the funerary rites and beliefs of Zoroastrianism, the religion of Iran, which continued to practise sky burials through to the twentieth century. One branch of the Zoroastrians, the Parsees of India, may well still practise excarnation today, and it is from these people that we have learned much about the very ancient rituals and customs surrounding this archaic tradition, which almost certainly originated among the neolithic peoples who inhabited the mountains of Kurdistan. This rugged, mountainous region once formed part of the ancient kingdom of Media, and it was here that, in the fifth century BC, the Greek historian Herodotus witnessed members of the priestly caste known as the Magi (from which we derive words such as ‘magic’ and ‘magician’) officiating at rites of excarnation.6

The Mandaeans, who following their arrival from Egypt are supposed to have settled in the area of Harran, also record that their most distant ancestors practised sky burials.7

Excarnation was widespread throughout Eurasia during neolithic times. Wherever evidence of its existence has been found, the cult of the vulture is also generally present. The obscure origins of these religious practices are, however, particularly relevant to this debate. Aside from the evidence we now have for the existence of the death cult of the vulture at Nevali Çori during the late ninth millennium BC, other evidence for its presence in the region during this same early period has come from an important discovery made at the Shanidar cave in Iraqi Kurdistan. This enigmatic location overlooks the Greater Zab river, which was seen as one of the four rivers of paradise. As mentioned earlier, it was here that during the 1950s the earliest known evidence for the use of hammered copper came to light in the form of an oval-shaped pendant dating to 9500 BC.

During these same excavations, palaeontologists Ralph and Rose Solecki uncovered, alongside a number of goats’ skulls, a large quantity of bird remains, consisting mosdy of entire wings of large predatory birds covered in patches of red ochre, which was sprinkled over burials in neolithic times.8 Carbon-14 dating of organic deposits associated with the bones produced a date of 8870 BC (+/-300 years),9 400 years prior to the accepted foundation date for Nevali Çori.

The bird wings were shipped off to the United States, where they were examined by Dr Alexander Wetmore of the Smithsonian Institution and Thomas H. McGovern, a graduate student in the Department of Anthropology at Columbia University. They identified four separate species present and as many as seventeen individual birds: four Gyptaeus barbatus (the bearded vulture), one Gyps fulvus (the griffon vulture), seven Haliaetus albicilla (the white-tailed sea eagle) and one Otis tarda (the great bustard) – the last being the only species still indigenous to the region. There were also the bones of four small eagles of indeterminable species.10 All except for the great bustard were raptorial birds, while the vultures were quite obviously carrion-eaters, and, as Rose Solecki was later to comment, were ‘thus placed in a special relationship with dead creatures and death’.11

Of the 107 avian bones identified, 96 (i.e. 90 per cent) were from wings, some of which had still been in articulation when buried. Slice marks on the bone ends also indicated that the wings had been deliberately hacked away from the birds by a sharp instrument, and that an attempt had been made to remove the skin and feathers covering at least some of the bones.12

Rose Solecki believed that the bird wings had almost certainly formed part of some kind of ritualistic costume, worn either for personal decoration or on ceremonial occasions.13 She also realised that they constituted firm evidence for the presence of an important religious cult at the nearby neolithic village of Zawi Chemi, for as she was to conclude in an important article written on the subject:

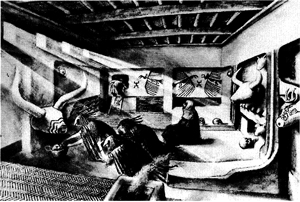

The Zawi Chemi people must have endowed these great raptorial birds with special powers, and the faunal remains we have described for the site must represent special ritual paraphernalia. Certainly, the remains represent a concerted effort by a goodly number of people just to hunt down and capture such a large number of birds and goats.14 . . . [Furthermore, that] either the wings were saved to pluck out the feathers, or that wing fans were made, or that they were used as part of a costume for a ritual. One of the murals from a Çatal Hüyük shrine . . . depicts just such a ritual scene; i.e., a human figure dressed in a vulture skin . . .15

Çatal Hüyük is the name of what is plausibly the most important neolithic site in the whole of Anatolia. First identified in 1958 by a British archaeological team headed by prehistorian James Mellaart, this double occupational mound near Konya in central Anatolia revealed a vast sub-surface metropolis which Mellaart began excavating in 1961. It was found to consist of a whole network of interconnecting dwellings and cult shrines belonging to an extraordinarily advanced community that thrived between 8500 and 7700 years ago.16 Nothing like this had ever been anticipated, let alone found, before in the Near East. The magnificence of its art, tools, weapons and skilfully fashioned jewellery showed a level of technology and sophistication which has forced archaeologists to review completely their understanding of the development of civilisation.

Following four seasons of excavations at Çatal Hüyük, Mellaart had managed to uncover and restore a series of extraordinary shrines that formed an integral part of the city complex and could be accessed only from adjoining rooms. They revealed all kinds of strange reliefs and murals that included life-size bulls’ heads (or bucrania) with horns emerging from plaster-covered walls; leopards in high relief, either stamped with trefoil designs or spread-eagled in the birth position; and human breasts moulded from plaster – in the walls behind which archaeologists found actual griffon vulture skulls, their bills protruding to form nipples.

Most important of all was that in many of the shrines the walls were adorned with enormous skeletal-like representations of vultures. Some were shown alighting on wooden-framed excarnation towers, in the process either of devouring the flesh of the dead or taking into their care the head of the deceased, which was looked on as the seat of the soul.17 The birds’ characteristic bald heads, short legs and visible crests easily identified them as griffon vultures.18 Other wall-scenes showed not vultures themselves but men or women adorned in the paraphernalia of the vulture. These could easily be identified as shamans, and not birds, by virtue of the fact that they had articulated legs – a conclusion openly drawn by those who have made careful studies of these extraordinary murals.19

Alan Sorrell’s evocative image of vulture shamans performing magical rites in one of the underground shrines at Çatal Hüyük, c. 6500 BC.

The cult of the vulture thrived at Çatal Hüyük, while further evidence of excarnation has come from the discovery of secondary burials.20 As at Nevali (pori and several other neolithic sites in the Near East, the presence of decorated skulls found inside the shrines shows that ancestor worship and oracular communication were also practised here.21

Harald Hauptmann does not accept that there is any link between the vulture shamanism of Çatal Hüyük and the clear vulture and bird-men imagery that predominates the art of Nevali Çori.22 This is despite the fact that he admits openly that there is a clear connection between birds and human beings intended by the sculptures and statues, and that birds and mixed beings ‘appear to have taken a special meaning in cult events’ within the community.23

We know from the evidence of bird wings found in the Shanidar cave that a highly developed form of vulture shamanism was present among early neolithic villages during the ninth millennium BC. Furthermore, the high culture present at Kurdish sites such as Nevali Çori and Çayönü during this period was also present in central Anatolia, as the agate bead necklace from Ashikli Höyük clearly demonstrates. This item, and others like it, was almost certainly manufactured by the skilled bead-making artisans of Çayönü. It suggests that the cult of the vulture developed in the fertile valleys and foothills of Kurdistan before being carried into other regions, including central Anatolia, where it was inherited by much later communities such as the one at Çatal Hüyük, c. 6500 BC.

With this knowledge, I feel it unreasonable to suggest that the cult of the vulture was not present at Nevali Çori during the ninth millennium BC, especially as the Shanidar cave is only 465 kilometres (290 miles) away. Indeed, it is highly likely that it was present among many more of the neolithic communities of Turkish and Iraqi Kurdistan.

If this is so, then I find it beyond coincidence that in the Edflx Building Texts the ancestral gods, or divine Sages, are referred to specifically as birds, with tides such as the Falcon and the Winged One. Were the Elder gods not falcons at all, but vulture shamans? Could it be possible that the death cult of the vulture originated among the Sphinx-building culture of palaeolithic Egypt before being carried into the Near East by its descendants?

Should this be so, then we must explain the specific references, not to vultures but to falcons, in the Egyptian texts. In my opinion, the transition from carrion-eater to bird of prey may well have occurred long after the age of the Elder gods, perhaps as late as predynastic times, when the falcon, or hawk, became an important totem in the wars between the Horus-kings of Heliopolis and the Set tribes of southern Egypt. Perhaps it became more appropriate to see the ancestral gods not as reviled vultures but as fighting falcons. It is certainly known that the Hebrews deliberately edited out the vulture from early stories and replaced it with the more acceptable image of the eagle,24 so perhaps the same thing happened in Egypt as well. The vulture was in fact an important bird in Ancient Egyptian myth and ritual, where it became the symbol of Mut, the wife of Amun, Meretseger, goddess of the Theban necropolis, and Nekheb, the principal goddess of Upper Egypt. Unfortunately, their respective cults, all centred in the south of the country, appear to have been latecomers to the Egyptian scene, and probably originated with foreign invaders who entered the Nile valley from the east during predynastic times.

The evidence emerging from Nevali Çori hints strongly at the fact that its sculpted statues and carvings depict shamanic individuals adorned in coats and head-dresses of vultures’ feathers. They, it seems, were the community’s prime movers during the early neolithic period, c. 8400–7600 BC. Yet despite the firm presence of vulture imagery in the cult building throughout its three different phases of construction, many of the anthropoid bird statues seem almost naive, crude even, when placed alongside the aforementioned serpent-headed vulture statue, or compared with the minimalistic art of the great monolith.

It would appear that, living alongside the highly skilled artisans who designed and created the earliest sculptures and carvings at Nevali Çori, there existed another class of individual responsible for the somewhat cruder art, which included many of the later human bird statues. By representing them in artistic form, it seems almost as if they were attempting to please the elders, priests or rulers of the community. It points clearly towards the conclusion that there were two distinct groups of people present at Nevali Çori, and presumably at other early neolithic sites as well. One was a ruling body, who seem to have been synonymous with the human bird, or vulture shamans, depicted in art form, while the other was made up of the remainder of the community, which probably consisted of an assortment of builders, labourers, farmers and shepherds, as well as more specialised artisans and craftsmen.

THE SERPENT-HEADED ONES

A more detailed profile of the neolithic ruling elite, who are likely to have been behind many of the innovations and technological achievements at sites such as Nevali Çori and Çayönü, has proved difficult. To learn more we must bring the clock forward another 2000 years.

The pre-pottery phase of the neolithic era was followed by the gradual emergence all over the Near East of fired and painted pottery. The date of its first appearance varies from area to area, although in eastern Anatolia it was introduced some time between 7600 and 5750 BC. The latter date marks the entrance-point of an entirely new culture known as the Halaf, after Tell Halaf, an occupational mound situated above the Khabur river near the village of Ras al-’Ain on the Syrian-Turkish frontier. It was here just before the First World War that a German archaeologist named Max Freiherr von Oppenheim first identified the presence of their distinctive glazed pottery and gave them this tide.25 The Halaf culture thrived all over Kurdistan between 5750 and 4500 BC, and they are thought by archaeologists to have been the prime movers behind the much-prized trade in the black volcanic glass known as obsidian. This was obtained in a raw state from an extinct volcano known as Nemrut Dağ situated on the south-western shores of Lake Van.26

In around 4500 BC a new culture entered the Near Eastern arena. Known as the Ubaid, they began to occupy many of the sites previously held by their predecessors, the Halaf. From here the Ubaid spread gradually southwards to form new communities, including one at Tell al-’Ubaid, near the city of Ur in southern Iraq, from which their name derives. Their lengthy presence in the Fertile Crescent almost certainly influenced the spread of Mesopotamian civilisation between 4500 and 4000 BC.

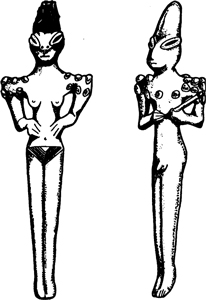

The Ubaid are perhaps most remembered for the strange anthropomorphic figurines, several centimetres in height, which they placed in the graves of their dead. These were either male or female (although predominantly female), with slim, well-proportioned naked bodies, broad shoulders, as well as strange, elongated heads and protruding snouts, which scholars generally describe as ‘lizard-like’ in appearance.27 Each has slit eyes, made of elliptical pellets of clay pinched together to form what are known as ‘coffee-bean’ eyes. On top of the head, many examples originally bore a thick, dark plume of bitumen, thought to represent a coil of erect hair. Each one also displays either female pubic hair or male genitalia.

Every figurine is unique. Some of the female examples stand erect with their feet together and their hands on their hips. At least one male statue holds what appears to be a sceptre of office, plausibly a symbol of divinity or kingship. Oval-shaped pellets of clay that cover the upper chest, shoulders and back of some of the statues are almost certainly representations of beaded necklaces, which may act as symbols of authority.

The most compelling of all the Ubaid figurines are the ones that show a naked woman cradling a baby to her left breast. The infant’s left hand clings on to the breast, and it seems to be suckling milk. More curious is the fact that the children also have reptilian heads, implying that, for some strange reason, the Ubaid would appear to have been making representations of individuals whom they believed actually possessed these distinctive features.

Two examples of Ubaid figurines – one male and the other female -c. 4500–000 BC.

The Ubaid figures have often been identified by scholars as representations of the Mother Goddess28 – a totally erroneous assumption since some examples are clearly male. Sir Leonard Woolley, the British archaeologist who first identified the Ubaid’s existence in Mesopotamia following his excavations at Tell al-’Ubaid during the 1930s, concluded that they represented ‘chthonic deities’ – i.e. underworld denizens associated with rites of the dead.29 Furthermore, it seems infinitely more likely that they do not represent lizards, as has always been thought, but serpents. Lizards play no role whatsoever in Mesopotamian mythology, which was undoubtedly influenced by the much earlier beliefs of the Ubaid.

Although these distinctive serpentine figurines were unique to the Ubaid, less abstract representations of snake-faced individuals with huge almond-shaped eyes have been found at the neolithic village of Jarmo in Iraqi Kurdistan.30 If you recall, it was during excavations here in the 1950s that the earliest known evidence of lead smelting was unearthed by Robert Braidwood and his team. These lightly baked heads date to as early as 6750 BC, and so suggest that this distinctive form of serpentine art developed first in the highlands and foothills of Kurdistan before gradually being transferred down on to the Iraqi plains some time around 4500 BC.

Much can be said about the snake in Mesopotamian mythology. It is known to have been associated with divine wisdom, sexual energy and guardianship over otherworldly domains. The Ubaid’s belief in serpent-headed individuals implied either that they felt there existed individuals who bore physical features that could be construed as serpentine in nature, or that they represented shamans whose practices focused on the cult of the snake, something I have shown elsewhere to be integrally linked with the culture and customs of the Kurdish tribal religions over the past several thousand years.31

To compare a person’s face with that of a snake, whether it be in an abstract or direct manner, seems a rather peculiar thing to do, unless, of course, there is good reason to do so. Among the American jazz-clubs of the 1930s, the term ‘viper’ was used to describe musicians who played for long hours, sustaining their creativity by consuming vast amounts of marijuana. Amid the smoky haze, their long, gaunt expressions and puffed-up eyes, further highlighted by low light, would give the appearance of snake-headed people playing on the stage. The term ‘viper’ was so common among the jazz community between the 1930s and 1950s that it became more generally used to describe ‘pushers’, those who actually sold or dealt in illicit narcotics.32 In this knowledge, it seems clear that if a person were considered to have had a face like a viper, then it implied that he had long, gaunt features with slit-like eyes comparable with the earliest baked-clay figurines found at Jarmo and dating to 6750 BC.

An example of the curious baked clay anthropomorphic heads found at Jarmo in Iraqi Kurdistan, and dated to c. 6750–5750 BC. Note the elongated facial features and almond-shaped eyes.

Was it possible that among the inhabitants of the neolithic, as well as the subsequent Halaf and Ubaid, cultures of Kurdistan there existed a class of individual with facial features that were thought to resemble those of a snake?

If the Ubaid figurines were therefore created to represent these characters, then who might these people have been? Why did the community feel it necessary to appease them in this manner? Was it a similar case at Nevali Çori, where the ruling priests would seem to have been artistically represented in a naive manner by those who treated them almost like gods? Could the same thing have been occurring in the case of the serpent-headed figurines found both at Jarmo and among the much later Ubaid graves? Were they too attempting to portray their ruling elite, or at least some memory of them, in a highly abstract form?

Such wild ideas are not stated lighdy, for there is firm evidence to suggest that among the Halaf and later Ubaid communities of Kurdistan there really did exist a ruling elite of quite striking appearance and character.

LONG-HEADED ELITISM

Tell Arpachiyah is an occupational mound located near Mosul in the foothills of Iraqi Kurdistan. It dates to the Halaf period and is looked on by archaeologists as a specialised artisan village that produced painted polychrome pottery of exceptional quality. It is known to have had cobbled streets, rectangular buildings, some for religious purposes, like those at Nevali Çori and Çayönü, as well as round buildings with domed vaults like the tholoi burial houses of Bronze Age Mycenaean Greece. Finds have included steatite pendants and small discs marked with incised designs that have been interpreted as early examples of the more well-known stamp seals used so much by later Mesopotamian kingdoms such as Akkad and Sumer, and, after their fall, Assyria and Babylon.

During excavations at the site of the tell by the archaeologist Max Mallowan in 1933, a large number of human burials were uncovered, many in an extensive cemetery that dated to the late Halaf, early Ubaid period, c. 4600–4300 BC.33 Most of the skeletons were badly crushed or damaged, but 13 skulls in a slightly better state of preservation were shipped off to Britain, where they were forgotten about for over 30 years. Then, in 1969, Mallowan published an article on these skulls, and this prompted two anthropologists, Theya Molleson and Stuart Campbell, to conduct their own examination of the remains. What they found concerning the appearance and genetic background of the skulls’ owners changes our entire perspective of the mysterious world in which these people lived around 6500 years ago.34

Molleson and Campbell found evidence to show that six out of the thirteen skulls had been artificially deformed during the life of the individual, the purpose being to increase the length of the cranium and create a more sloping forehead.35 Such deformations are usually achieved by skilfully wrapping circular bands, sometimes containing wooden boards, around the skull of an individual when still in infancy. In the past this practice was widespread in many parts of the world, particularly South America, and was conducted either for religious or superstitious purposes, as well as to distinguish a person from others not of his or her rank, caste or class.36

Knowledge of skull deformation at Tell Arpachiyah came as no surprise, for it had earlier been suspected by Max Mallowan, the original excavator, who even before the study made by his two younger colleagues concluded:

. . . we appear to be confronted with long heads, and there are certain pronounced facial and other characteristics which appear to imply that the possessors of this [Ubaid] pottery had distinctive physical features, which would have made them exceptionally easy to recognise.37

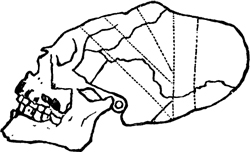

Elongated skull, showing the outline of bands used to create deformation during infancy. This strange process was practised in the Near East among the ruling elite of the Halaf and Ubaid peoples during the late neolithic period.

Skull deformation in prehistoric Kurdistan was itself interesting; however, Molleson and Campbell went on to realise something else of importance about the skulls. Some of the cranial abnormalities had not been induced artificially using head bands and blocks of wood, but were instead clearly genetic in nature,38 leading them to observe that ‘several of the individuals (including some without deformations) were related to each other’.39 In their opinion, this discovery showed that since the skulls derived from individuals coming from both the Halaf and Ubaid periods of occupation at the site, then the two cultures must have been genetically linked in some way.40 More significantly, they concluded that artificial deformation at Arpachiyah had been practised by ‘a particular group’ who must have been ‘genetically related’.41 They further added that the abnormalities present among this group suggest a degree of ‘inbreeding comparable to the prescribed cross-cousin marriages prevalent in the area today’.42 From the anatomical evidence available, it seemed clear to Molleson and Campbell that they were dealing with a family group who deliberately elongated their craniums to make themselves stand out from other groups in the community, almost like some kind of body uniform.

Cranial deformation among the Halaf and Ubaid peoples of the sixth and fifth millennia BC has been determined at several sites in northern Iraq,43 as well as at others in eastern Anatolia.44 Its exact purpose among these cultures who helped create the Mesopotamian races, and, in the case of the Ubaid, were the direct forerunners of the Mandaeans, is still a matter of speculation among anthropologists and archaeologists. Molleson and Campbell pointed out that such a ‘distinctive appearance would render the individual identifiable as to class or group even if taken prisoner and stripped of other visible accoutrements of status’.45 They also noted that this practice ‘has considerable potential for elitism’.46

Molleson and Campbell have proposed that the strange serpentlike figurines of the Ubaid period are abstract representations of these long-headed individuals - the tall bitumen ‘head-dresses’ and flattened faces being clear evidence of this association.47 They also point out that members of this same elite group are depicted in a highly stylised form on fired pottery dating to both the Halaf and Ubaid periods.48 Many of these images have, in addition to long heads, flattened, protruding faces, over and beyond that caused purely by skull deformation.49 Another, equally important characteristic is the presence on one example from the Halaf period, c. 4900 BC, of two individuals who have elongated heads from which trail curved lines that represent feathered head-dresses.50 Curiously enough, this painted pottery comes from a site called Tell Sabi Adyad, located on the Syrian-Turkish border, just 20 kilometres (12½ miles) south-south-east of Harran and 113 kilometres (70 miles) south of Nevali Çori.

CULT OF THE RATTLESNAKE

Molleson and Campbell suspected that the skull deformation found among both the Halaf and Ubaid societies was being used to ‘demarcate a particular elite group, either social or functional’, who were of ‘close genetic relationship’ and ‘hereditary and closely inbred’.51 Furthermore, the ‘shapes of the head may have had specific meaning’.52 Who were these long-headed individuals depicted in clay as anthropomorphic serpents and on pottery as priests or shamans wearing feathered head-dresses?

Artist’s impression of skull deformation among the Chinook tribes of North America. Note the boards and bands used to achieve this effect. A similar process took place among the chime priests of Mayan Mexico.

In an attempt to answer this question, we must switch our attentions to another part of the world altogether. Among the Mayan culture of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, a hereditary line of priests known as chanes, ‘serpents’, would apply bands to deform the heads of infants in order to give them what was known as a polcan - an elongated serpentine head. By doing this at an early age, the child became eligible for acceptance into the family of chanes, the people of the serpent who perpetuated the cult of the rattlesnake.53 The priesthood honoured Itzamna, or Zamna, a form of Ahau Can, ‘the great, lordly serpent’, who was believed to have taught their earliest ancestors the Mayan calendar system.54 In the corresponding tradition of the Aztecs, Zamna became Quetzalcoatl, the great ‘feathered serpent’ and divine wisdom-bringer. Just as the followers of Ticci Viracocha, the great civiliser of South America, were collectively known as the Viracocha, so the ‘king-priests’ of Quetzalcoatl were referred to in legend as Quetzalcoatls, ‘feathered serpents’.55

Is it possible that a priestly elite – like the Quetzalcoatls of the Aztecs and the chanes, or ‘serpents’, of the Maya – once existed among the foothills and fertile valleys of Kurdistan? If so, then did they also purposely elongate their heads like serpents and wear feathered headdresses in honour, or in memory, of ancient wisdom-bringers who entered their world at the beginning of time?

If, as seems likely, the ruling elite of the Halaf and Ubaid peoples saw themselves as descendants of this proposed group of anthropomorphic serpents, then it provides us with a meaning behind their use of skull deformation. Maybe they felt the need to resemble their divine ancestors, whom they saw as serpentine bird-men with viperous faces and elongated craniums that were likened to the shape of an egg – a primary symbol of first creation. Could this be why we find a carved stone head shaped like an egg and with a serpentine pony-tail facing out from a niche in Nevali Çori’s cult building? Was it meant to represent one of the shamanic descendants of the Elder gods, perhaps even one of the Elder gods themselves? Might the same be said of the beautifully executed serpent-headed ‘vulture’ statue and the hammer-headed bird-man that were also found in the building?

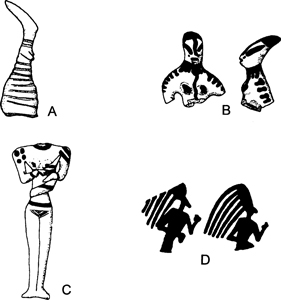

Four abstract examples of probable skull deformation found among Halaf and Ubaid art (after Theya Molleson and Stuart Campbell): a) A Halaf statue from Yarim Tepe, c. 5750 BC; b & c) Striking Ubaid figurines from Ur in southern Iraq, c. 4200 BC. Note the baby’s almost chilling features; d) Halaf pottery from Tell Sabi Adyad, c. 4900 BC. Note the stylised feathered head-dresses, plausibly denoting the practice of bird shamanism.

There is evidence to suggest that oversized craniums, or long heads, were a genetic feature of the elite group present among the Halaf and Ubaid cultures outside of skull deformation. All they did was accentuate what was already present. This is an important realisation since there is firm evidence for the presence among the Isnan and Qadan settlements of Egypt, c. 12,500–9500 BC, of individuals with oversized, long-headed craniums who have been likened to the Cro-Magnon Homo sapiens who thrived in this world many millennia before the rise of these advanced communities.56 Although these are unlikely to be representative of the Elder gods, it does prove that elongated craniums were a genetic feature of the Nilotic communities during the time-frame under question. If the Elder gods were genetically related to the Isnan and Qadan peoples, then it seems highly probable that they themselves possessed unique cranial features which included elongated heads. Could this be why their proposed Near Eastern descendants were seen as bird-men with the faces of serpents, because of their distinctive shaped skulls?

Other than the references to their appearance as birds, the Edfu texts tell us only that the primeval ones bore some kind of facial countenance,57 like the god-kings of Iran and the antediluvian patriarchs of Hebrew tradition. If this too related in some way to their facial features, then with their cloaks of feathers, both the Elder gods and their presumed neolithic descendants would have possessed quite striking appearances that may well have contrasted gready with the indigenous peoples of Kurdistan.

If the earliest priest-shamans at Nevali Çori and Çayönü really were the descendants of Egyptian Elder gods, did they also introduce the neolithic peoples to the practice of human sacrifice? Does this reveal a darker side to the Elder gods – one that by today’s standards would be considered as amoral and almost inhuman? Might this explain why one of the Shebtiu was known as ‘The Lord, mighty-chested, who made slaughter, the Soul who lives on blood’?58 Did they also help establish elitism based on a belief in divine ancestry? This idea – which I have outlined in great detail elsewhere – almost certainly went on to become the roots of divine kingship among the earliest civilisations of the Near East.

Billy Walker-John’s impression of a Neolithic priestly shaman like that thought to have formed the ruling elite at neolithic cult centres such as Nevali Çori and Çayönü in eastern Anatolia.

Although not so grand, the megalithic structures of eastern Anatolia bear a clear resemblance to both the Valley Temple at Giza and the Osireion at Abydos. Should it ever be proved that these neolithic structures really were the product of the same high culture, then it begs the question of what else the Elder gods might have introduced to the earliest neolithic communities of the Near East, and what exactly their role was in the genesis of civilisation. It is these pressing questions that we must now address in the next two chapters.