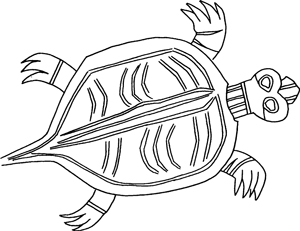

Many thousands of years ago the peoples of Kurdistan, from the mountains of Armenia through to the fertile valleys of Turkey and Syria, were united under the leadership of a ruling elite known as the Hurrians. These Indo-European-speaking warlords appeared almost out of nowhere during the third millennium BC and quickly drew together the many different tribal factions, who built beautiful cities and towns, and established a kingdom that lasted over 1000 years. In spite of the fact that history has recorded very litde about their sophisticated culture, we do know that they were the forerunners of both the Hittite empire of Turkey and the kings of Mitanni, or Naharin, who became Egypt’s allies during its Eighteenth Dynasty.

The Hurrians possessed their own unique religion which, although truly indigenous to Kurdistan, had a profound influence on the development of mythology down on the plains of Ancient Iraq. Many of their myths seemed to focus on the beliefs of the people who lived between the Upper Euphrates and Tigris rivers, where their great religious centre was ancient Harran, home of the Sabian star-worshippers. From ancient inscriptions we learn that one of the Hurrians’ greatest deities was Kumarbi, a dark water-god, comparable with Neptune in the Roman pantheon. His animal form was the pond turtle, and creation myths speak of him raising himself out of the primeval waters at the beginning of time. His hard, knobbly shell became the mountains, while the tears that fell from his eyes became the sources of the Euphrates and Tigris.1

THE CREATURE OF CANCER

The name Kumarbi derives from the Sumero-Akkadian root kumar, ‘dusky’, which, as previously stated, is the root behind the name given to the star constellation Cetus by the various Mesopotamian cultures. It is therefore safe to presume that Kumarbi, the dark water-god of the Hurrians, was linked directly with the Euphratean sea-monster.

So in addition to being a whale and a sea-monster, Cetus would also appear to have been equated by the peoples of the Upper Euphrates with the pond turtle – a symbol that even today features prominently in Kurdish folklore. It is emblazoned in abstract form on locally made kilim rugs, which are based on traditional designs that are known to date back several thousand years.2 The Kurds also see the pond turtle as the symbol of Khidir, a powerful spirit whose omnipotent influence is felt both on land and in water.3 In many ways he is the Kurdish equivalent of the Green Man, the living spirit of the wildwood, whose vine-sprouting stone face still gazes down from the Gothic masonry of hundreds of churches and cathedrals all over Europe. Khidir means ‘green’ or ‘crawler’, and it is said that he ‘dwells primarily in deep, still ponds’.4 More significantly, the turtle was likened to the Euphrates, since its waters were seen as slow-moving, in contrast to the Tigris, the fast-moving waters of which were compared with the swift movement of the hare.5

This age-old connection between turtles and Kurdistan might help explain a very curious limestone water-bowl found by Harald Hauptmann at Nevali Çori. In an almost naive manner, its unknown artist has chiselled in low relief an upright-standing turtle, each side of which is a naked figure, one male and the other female. Their hands are raised high in the air as if in an ecstatic state – Hauptmann suggests they are in fact dancers.6 The strange imagery on this unique water-vessel may well provide evidence to suggest that the indigenous peoples of Kurdistan have revered the sanctity of the pond turtle for at least 10,000 years, an astonishing realisation in itself. Yet the presence of the turde at Nevali Çori has even greater implications for our understanding of its geomythic relationship to the celestial horizon.

In the pre-dawn light of the spring equinox of 8000 BC, the stars of Cetus, the dusky constellation that dwells within the Gate of the Deep, would have been seen low on the south-western horizon. Strung between the ‘paws’ of this sea-monster – equated with both Tiamat and Kumarbi – and Rigel, the left foot of Orion, would have been seen the stars of Eridanus, the River of the Night and the celestial counterpart of the mighty Euphrates. This much we know. Yet if we were then to turn our heads towards the east, where the sun was about to rise in all its splendour, we would see that immediately above the horizon was the constellation of Cancer – the zodiacal sign that defined the precessional age after the final setting of Leo on the equinoctial horizon some time around 9220 BC.

Since classical times the star constellation of Cancer has been symbolised by the crab. Yet thousands of years before it gained this association, Cancer was looked on by the peoples of Mesopotamia as the turtle.7 Giorgio Santillana and Hertha von Dechend, the authors of Hamlet’s Mill, have argued that many primitive societies before the rise of civilisation were somehow aware of both the 12-fold division of the zodiac and the phenomenon of precession. If this is so, then it seems likely that the neolithic priest-shamans of the Upper Euphrates would have been aware of the astrological influences that governed the destiny of their own precessional age. I therefore find it curious that, similar to the mythology behind the constellation of Cetus, the Cancerian turtle is an amphibian linked not just with the pre-dawn equinoctial sky of the ninth millennium BC but also with Nevali Çori and the nearby river Euphrates. Could it be possible that the mythological traditions surrounding the stars of Cetus were so strong that they became closely interwoven with the star-lore attached to the constellation that defined the astrological influence of the age in question? Could the proto-memories of the ancestral homeland and the primordial watery chaos that existed before the beginning of time have influenced the very nature of the Cancerian age?

The Mesopotamia turtle, symbol of the god Enki, or Ea, the constellation of Cancer and the river Euphrates.

REALMS OF THE RIVER-GOD

To answer these questions we must look further at the myths and legends surrounding the god Enki. He was seen in Euphratean myth as presiding over the subterranean waters of the apsû, and in this capacity he was considered to bring forth the two great rivers, the Euphrates and Tigris, confirming his close association with this region, seen by Mehrdad Izady as the land of Dilmun, Enki’s paradisical realm. In representations of Enki, these two rivers were shown as twin streams flowing either from the god’s shoulders or from a vase held in one hand. Fish swim in the midst of the streams, like salmon attempting to ride the current to reach the source of a river.

Strangely enough, in a star-map that accompanies Aratus’ famous third-century BC discourse on Euphratean star-lore, the constellation of Eridanus is shown as a recumbent river-god, with a short beard and flowing locks, who holds in one hand a stalk of ‘some aquatic plant’, while his other hand rests on an urn, ‘whence flow right and left two streams of water’.8 Depictions of Eridanus found in other classical sources also show variations on this river-god theme, even though the figure is depicted occasionally as a reclining river nymph.9 Since we know that Eridanus was the celestial form of the Euphrates river, then it seems quite certain that Aratus’ river-god was simply a classical memory of Enki’s guardianship of the two great rivers.

The god Enki, or Ea, showing the waters of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers flowing from his shoulders. His two-faced minister stands behind him, while upon his hand rests the vulture – an abstract symbol of the neolithic cult of the dead.

In the light of Enki’s connection with the Euphrates in particular, it is perhaps not surprising to find that his main symbol was the turtle.10 This association obviously reflected the god’s affiliation with the subterranean waters of the apsû, which were believed to rise up into the terrestrial world through bottomless springs and ponds – domains of the pond turtle. Yet as the apsû also had a celestial counterpart, it made sense that the turtle was also seen as a constellation in its own right. This, of course, was Cancer, which became the spirit of the astrological epoch in which these traditions would appear to have first been laid down at neolithic temple sites such as Nevali Çori.

Confirmation that both Enki and the turde were linked with the equinoctial horizon during the Age of Cancer comes from the knowledge that the god’s other main animal form was the mythological goat-fish.11 In Mesopotamian tradition it was said that the turtle and the goat-fish struggled constantly to become Enki’s favourite animal; indeed, sometimes the turde is placed on the back of the goat-fish as if to show its ultimate superiority in this longstanding battle for supremacy.12

The turde can be associated with the constellation of Cancer, the equinoctial marker during the three building phases of Nevali Çori’s cult building, but what about the goat-fish? Did this creature also have a starry counterpart? The answer, of course, is yes. The goat-fish is the earliest known representation of Capricorn,13 the zodiacal constellation that lies in direct opposition to Cancer. In other words, as Cancer rose with the sun on the spring equinox, Capricorn would have been seen on the western horizon. At the autumn equinox, the roles would have been reversed, with Capricorn rising with the sun, while Cancer was on the western horizon. This opposing relationship between the two zodiacal constellations would have created a visual effect something akin to a celestial seesaw in the skies above Nevali Çori on the equinoxes during the Age of Cancer.

This, then, was the eternal struggle for supremacy between these two aquatic creatures, both familiars of the god Enki. The god himself played a prominent role in the wars that waged between the demon-brood of Tiamat and the Anunnaki, the name given to the gods of heaven and earth in Mesopotamian myth. Enki was thus connected not just with the sources of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, which rose in the mythical land of Dilmun, but also with the key components of the starry sky as it would have appeared before sunrise on the spring equinox during the astrological Age of Cancer, estimated to have occurred c. 9220–7060 BC.14

The Mesopotamian goat-fish, symbol of the god Enki and the constellation of Capricorn.

THE REPULSIVE ONES

Ancient cuneiform texts tell us that, following the creation of the physical world, Enki, having departed from Dilmun, provided mankind with the divine arts and crafts that enabled him to achieve a state of civilisation:15 this is a statement that makes complete sense of archaeological discoveries made on the plains of Mesopotamia. The oldest known place of worship in pre-Sumerian Iraq is Eridu, a city located by the mouth of the Lower Euphrates on the edge of the Persian Gulf. Here, a temple was first established in around 5500 BC, and at the very earliest occupational levels excavations have revealed the presence of countless numbers offish bones.16 This can be seen as evidence of supplication to some proto-form of Enki, who later became the patron god of Eridu. What exactly was worshipped here, 2000 years before the rise of the Sumerian civilisation, remains uncertain. However, we do know that the worship of Enki was linked very much with the fecundity of the irrigated lands fed by the Euphrates. This integral link with the river eventually led to Enki being represented in reliefs, particularly at Eridu, as a man adorned in the garb of a fish.17

The memory of the knowledge and wisdom imparted by Enki to the first inhabitants of ancient Iraq, some time around 5500 BC, was recorded by Berossus, a celebrated priest and scribe of Babylon’s temple of Bel (or Bel-Marduk), who lived during the third century BC. He composed a three-volume discourse on the legendary history of his race, including their forebears the Sumerians, entitled Babyloniaka. Sadly, our only knowledge of this now lost work comes from quotations or commentaries found in the writings of other authors, such as Alexander Polyhistor, Apollo-dorus, Abydenus and Flavius Josephus, which were themselves saved by being preserved in the works of much later Christian writers, such as Eusebius of Caesarea (AD 264–340) and George Syncellus (fl. ninth century). These passages include curious accounts of the visits made to Babylon by a strange fish-man named Oannes, who was said to have appeared out of the ‘Erythraean Sea’ in the ‘first year’ and spent his days among mankind, providing them with:

. . . an insight into letters and sciences, and arts of every kind. He taught them to construct cities, to found temples, to compile laws, and explained to them the principles of geometrical knowledge. He made them distinguish the seeds of the earth, and shewed them how to collect the fruits: in short, he instructed them in every thing which could tend to soften manners and humanize their lives. From that time, nothing material has been added by way of improvement to his instructions.18

So wrote Berossus concerning the foundations of the Babylonian (i.e. the preceding Sumerian) race. Of Oannes himself, it was said that he was an Annedotus, a ‘repulsive one’, and that his ‘whole body was that of a fish’. Furthermore, ‘that under the fish’s head he had another head, with feet also below, similar to those of a man, subjoined to the fish’s tail. His voice too, and language, was articulate and human; and a representation of him is preserved even to this day’19 Berossus also recorded that after Oannes had conversed with mortal kind, he would return to the sea where he ‘passed the night in the deep; for he was amphibious’.20

Berossus goes on to state that following the appearance of Oannes, 10 great kings reigned over Babylon (i.e. Sumer), the last of whom was Xisuthrus, during whose reign occurred the ‘great deluge’, a subject I have examined in great detail elsewhere.21 Before this time a total of five (one version says seven)22 Annedoti, the first of whom being Oannes himself, were said to have appeared in the land of Babylon.23

It is impossible now to know exactly what Berossus was attempting to convey by preserving the strange legends surrounding the appearance of these wisdom-bringing fish-men. It is, however, quite clear that Oannes himself is simply a Greek rendering of Enki, based on his Akkadian name Ea. The five Annedoti, on the other hand, correspond very well with the five ‘ministers’ said to have served the monster serpent Chorzar, the daughter of Thalassa – the Greek name for Tiamat – in the curious writings of the Peratae gnostics.24

The fact that Berossus cites Oannes as having appeared out of the Erythraean Sea – the ancient name for the Arabian Sea,25 connected via a channel to the Persian Gulf – would seem at first to contradict the knowledge that Enki was linked with the sources of the Euphrates and Tigris. This conclusion is also suggested by the presence close to the mouth of the Euphrates river of the principal temple of Enki at Eridu. However, in view of Dilmun’s association with Enki and the sources of the great rivers, it seems clear that something is wrong here, and the confusion almost certainly derives from the Sumerian belief that the ‘mouth’, or estuary, of a river was its source, out of which the waters flowed.26 Admittedly, this same argument has been used by Mesopotamian scholars to prove exacdy the opposite – that the Sumerians saw the source of a river as its ‘mouth’, or estuary—but to me this seems entirely wrong.27

Kulullu or fish-man – a form of the god Enki, Ea, A’a or Oannes, the bringer of civilisation in ancient Hurrian and Mesopotamian mythology.

Great confusion has arisen in this respect, and it seems certain that it existed even in Berossus’ day, when he spoke of Oannes and the rest of the Annedoti coming out of the Erythraean Sea. If, as seems more likely, he was working from original Akkadian or Sumerian sources, which spoke of them coming out of the ‘mouths’ of the rivers, then he would have presumed this meant the open sea. In my opinion, there is every reason to believe that in the story of Oannes, Berossus was recording an age-old memory concerning the descent from the land of Dilmun of individuals, personified as the five Annedoti, who were seen as having brought the art of civilisation to the earliest peoples of the Fertile Crescent.

That the leader of these amphibious wisdom-bringers was a form of the god Enki, or Ea, seems to link them direcdy with the ruling elite, the astronomer-priests of the earliest neolithic communities of eastern Anatolia. Their starry wisdom, apparently established during the astrological Age of Cancer, would appear to have become embroiled in much later Mesopotamian myth. This astronomical mythology would seem to have included an assortment of clearly aquatic themes and symbols such as the sea-monster Tiamat as the personification of the Gate of the Deep; the starry stream Eridanus as the celestial Euphrates; the turtle as the creature of Cancer; the goat-fish as the earliest form of the constellation of Capricorn; and, of course, Enki himself, who was declared a kulullu, a fish-man.

Yet who, or what, exactiy was Enki? Was he simply a mythical being, or had he been an actual person – a living god who once inhabited the land of Dilmun as the legends imply?

As previously noted, the Akkadians of northern Iraq revered Enki under the name of Ea, from which we derive the name Oannes. I was therefore intrigued to discover that in the Indo-European language of the Hurrians he was known as A’a.28 This strange sounding name is composed of two letter As broken by a missing consonant denoted by a character known as an aleph. Although this has no direct English translation, it is generally interpreted as a guttural A.

Scholars of Mesopotamian studies would consider that the Hurrians borrowed the myths surrounding Ea from the Akkadians, some time during the third millennium BC. If, however, he was of Upper Euphratean origin, as now seems clear, it is far more plausible that he began his life as a Hurrian god. Regardless of where exactly his myths might have originated, in the name A’a we are now presented with an Indo-European form of Mesopotamia’s great civiliser. This is important, for as we know from the Edfu Building Texts, the names given to the leaders of the Shebtiu who ‘sailed’ away to another primordial world after completing the second period of creation at Wetjeset-Neter are Wa and ‘Aa. This second name, which is composed of two letter As prefixed by an aleph, is phonetically the same as the Hurrian A’a. Both are pronounced something like ah-ah.

Since we have already identified the Shebtiu as one of the primary names of the Elder gods who departed Egypt for the Near East in around 9500 BC, I find it beyond coincidence that one of their two leaders bears exacdy the same name as the great wisdom-bringer of Hurrian tradition. Is it possible that their neolithic forebears somehow preserved the name of one of the original Elder gods who arrived in the mythical land of Dilmun following the age of darkness and chaos personified by Tiamat, the dragon of the deep? Do A’a, Ea and Enki derive their root from one of the two leaders of the Shebtiu? Can it be possible that the great deeds of this living god were preserved across millennia? Were they then transformed into the story of how the knowledge of civilisation was passed on to humanity by the amphibious being spoken of so poignantly in the writings of Berossus under the name of Oannes?

This kulullu, or fish-man, would appear to have become a symbol of the starry wisdom mastered at astronomically aligned observatories such as the cult building at Nevali Çori on the Upper Euphrates, where the descendants of Egypt’s Elder gods would seem to have established their first settlements during the epoch which we define today as the Age of Cancer. Yet A’a, Ea, Enki or Oannes would seem to have been far more than simply a later Mesopotamian memory of the Elders’ influence in the Near East, for in my opinion his image is embodied in the minimalistic anthropomorphic form carved on the enormous rectilinear monoliths at Nevali Çori. As I have previously noted, the figure’s hands end not in four fingers and a thumb (as is present on other reliefs found at the site, such as the ‘dancers’ on the limestone water-bowl) but in five fingers of equal length which are, in my opinion, meant to signify the flippers of an amphibious creature.

Just as the five Annedoti appear to be synonymous with the five ‘ministers’ of Chorzar, the cosmic serpent entrusted with the power of Thalassa, or Tiamat, so the neolithic ruling elite of the Upper Euphrates became the first ‘ministers’ of the cosmological doctrine that emerged from the dark primeval world that lay beyond the Gate of the Deep, the starry doorway through to the Black Land of Egypt. It was from these strange beginnings that civilised life arose in the fertile valleys of eastern Anatolia, northern Syria.

THE BIRTH OF SUMER

In the opinion of archaeologists and historians alike, the city-states of Sumer constitute the earliest known civilisation of the Old World. From their very first foundations in the sixth millennium BC, they grew over a period of 3000 years to become the most sophisticated society on earth. As was ably demonstrated by Samuel Noah Kramer in his classic work History Begins at Sumer, the number of ‘firsts’ attributed to the Sumerians is virtually endless. They designed the first coloured pottery. They conducted the first medical operations. They made the first musical instruments. They introduced the first veterinary skills and developed the first written language. They also became highly accomplished engineers, mathematicians, librarians, authors, archivists, judges and priests. Yet despite all this no one is quite sure who the Sumerians were or why they would appear to have evolved so much faster than any other race.

Suggested migrational route of the Egyptian Elder culture, the proposed gods of Eden, following their dispersion into the Near East, c. 9500–9000 BC.

There is ample evidence to show that the innovative capabilities of the Sumerians derived from what they inherited from their mountain forebears, such as the ruling elite of the Halaf and Ubaid cultures. It was from these priest-shamans, the descendants perhaps of Egypt’s Elder gods, that they gained their knowledge of civilisation.

Completing the cycle is the knowledge that the earliest Sumerians, as well as the pre-Phoenician mariners of Byblos in Lebanon, entered Egypt during predynastic times and helped initiate the Pharaonic age, which began with the institution of the First Dynasty in around 3100 BC.29 In many respects, this migration to Egypt was like returning to the source – returning to their ancestral homeland. This idea is expressed no better than in the pilgrimages made to the Great Sphinx by the star-worshipping Sabians of Harran during the early second millennium BC, or in the firm belief of the Mandaeans that their most ancient ancestors came originally from Egypt.

The influence of the peoples of Mesopotamia on the first three dynasties of Egyptian history initiated the pyramid age. Here, all the ideas of those who had preserved the seed of the Elder culture, such as the Divine Souls of Heliopolis and the Companions of Re, were finally realised and put into effect. Although they might have been the inheritors of the Elder gods’ Egyptian legacy, which seems to have included the art of sonic technology, these individuals were probably only small religious groups who kept alive archaic traditions at cult centres such as Heliopolis in the north and Abydos in the south. Alone they could do very little. They had no real influence over the ruling tribal dynasties and were not in a position to reignite the splendour of their divine ancestors. Yet with the aid of incoming architects, craftsmen, designers, religious leaders, as well as a new ruling elite, they were able to begin the process of continuing the glories of the Elder culture, which had dispersed to various parts of the globe several thousand years beforehand.

Imhotep was the architect of the first ever stone pyramid, built at Saqqara during the Third Dynasty for his king, the mighty Djoser. Its stepped design is very reminiscent of the seven-tiered ziggurat structures of Mesopotamia, while the façades of the temenos walls that surround the pyramid complex are strikingly similar to the design of the exterior walls of cult buildings in Ancient Iraq – the temple of Enki at Eridu being a prime example.

Such comparisons between Mesopotamia and Egypt have long been known to Egyptologists. Yet the greatest significance of this external influence on the architecture of Ancient Egypt is the sheer fact that within just 150 years of Djoser’s reign, it had led to the Elder culture’s surviving technological capability being combined with local building skills to produce what is arguably the world’s greatest architectural achievement, the Great Pyramid. This monument – built to a design based on archaic knowledge preserved by the astronomer-priests of Heliopolis – was the crowning glory, not only of Egypt, but of everything that had been secretly kept alive since the age of the netjeru-godsy the epoch of the First Time. The precision science, geometry, orientation, stone cutting, hole drilling and architectural planning of the Great Pyramid was the result of a legacy preserved not simply by the wise old priests of Egypt, but by a number of diverse cultures across the Near East. Their most distant ancestors were the neolithic gods of Eden, whose own forebears had left Egypt for the fertile valleys of eastern Anatolia during the geological and climatic upheavals that had accompanied the end of the last Ice Age. It is to these unique individuals, the living descendants of a divine race with a lifestyle that would seem almost alien today, that we owe the genesis of civilisation.