I DREAMED I DRANK A NIGHTMARE

Don’t you get it? You frightened young man. AIDS didn’t start with Rock Hudson. It was around long before either of us heard about it.1

In 1992, I met Brian Regnaert at Bill’s Bar in Boston. He was working as a bartender while trying to get his modeling career going. I met him through my friend, Jeff Marshall, who was also tending bar with Brian. Later, Jeff told me about his friend Demetrius who owned a small shop on Newbury street called The Gods. A fellow photographer, Demetrius had taken a number of photos of Brian that he wanted to show me. When I saw them, I thought, “What a stunning creature!” Such a great beauty. Brian had been photographed for Guess Jeans by Bruce Weber and was becoming more sought after by many photographers. We became fast friends. It was a chemical thing, an inexplainable draw—we really enjoyed being together. Although we became very close, it never turned romantic—even if I hoped it would.

Eventually, Brian said he wanted to move to New York. His career was picking up and he wanted to make a mark in the big city.

“Why don’t you come stay with me?” I said to him.

“Really?” he asked.

“Sure! You can stay as long as you need—until you find your own place.”

He was very excited. There was an innocence about him wanting to move to the city, and I expect he was thinking: “Oh, I get to go to New York! I can live with Michael Alago ’cause he invited me!”

When Brian finally arrived in 1993, he quickly moved in. We had home-cooked dinners almost every night—mostly pasta, because it was easy. I usually created a very tasty tomato basil sauce which I made from scratch. We ate these dinners while watching movies on TV. It began to feel like a safe and warm home life.

We were also at concerts and the theatre all the time. I took him backstage to everything. We went to see the Rolling Stones, Patti Smith, and Sisters of Mercy; we even went to Joey Ramone’s birthday party, where we hung out with him at his apartment. We loved going out to all the downtown cultural events as well as to movies. At one point we saw the film, True Romance, which became Brian’s favorite. Over the course of these few months, it turned into one of the most significant friendships of my life, and even more importantly, because he was there when I started to get sick.

By 1994, AIDS was the leading cause of death in the United States for people between the ages of 25 and 44.2 “Sex was dangerous. Blood was a killer. No one was truly safe. . . . 41,669 United States citizens were dead due to complications from AIDS.”3

Although I had been asymptomatic since 1983 when I was diagnosed as HIV-positive, in 1992, I had a bout of the mumps. I thought it was a little strange that someone in their early thirties would develop a childhood disease, and it seemed strange to my doctor, Barbara Starrett, as well. I recovered from it and felt fine, but that was the beginning of my AIDS nightmare.

About four months after Brian moved in, the illness reared its ugly head again. I developed anemia; I started shitting constantly and was unable to keep anything down. So, of course, I started to lose weight; in fact, I was wasting away. I had an 18 T-cell count, which basically meant I didn’t have an immune system at all. I also noticed my chest becoming heavy. I felt shaky, and my thoughts became a bit manic. Anything and everything was attacking my body.

I remember when I first told Brian I was sick. We were sitting out on my terrace enjoying a warm summer sun as it disappeared behind the buildings. It was a hard thing to tell him, and I could feel my tears welling up.

“I don’t know how to tell you this—” I said.

“What?”

“I’m positive.”

“Positive?”

“HIV positive,” I said to him. “I have HIV.”

There was a long pause and then as my tears started spilling out, Brian began crying too. He said he had never known anyone with HIV—he knew about the disease—but it had never hit so close to home. He was devastated.

Being HIV-positive is a confirmation that HIV antibodies have been activated; it does not mean that person has—or will have—AIDS. Detectable antibodies in the bloodstream are spirits of the brave cells lost as they waged a battle against the virus. Before labs could measure the amount of virus in a person’s blood, the Center for Disease Control (“CDC”) created a somewhat arbitrary baseline of 200 CD4+ T-lymphocytes (“T-cells”) to distinguish immuno-decline.4

This was at a time when all my male friends, in and out of the music business, were dying. I was filled with fear. There was no cure. There was no solution.

Because of my 18 T-cell count, one of the first things to hit me was PCP pneumonia.5 Dr. Starrett started me on Pentamidine6 inhalers, which I took to work with me and used behind closed doors. But very quickly, it was clear that the medication wasn’t working. I was getting worse. She immediately started me on intravenous Pentamidine.

Dr. Starrett insisted I go to the hospital immediately. But I absolutely refused. I fought tooth and nail not to go into the AIDS ward at St. Vincent’s Hospital. The situation in the ward was dire. I had so much fear that, to me, going into the AIDS ward signaled death.

Smoking, sun damage, tooth decay, politics, blocked calls, money troubles, talk of a cure: these are just some of the things you no longer care about when your doctor has given up on you and you’re one of a chorus of guys awaiting your big death number on the 7th floor of St. Vincent’s.7

Luckily, I had the best health insurance. I had fifteen to eighteen days of a private nurse coming to my home and, even more fortunately, Brian was there.

Brian’s mother was a nurse. When he was growing up, he went with her to visit patients in the hospital. He was raised with a real sense of caring for others and, in many unforeseen ways, he was heaven-sent.

So, I stayed home. Barbara accepted it, even though she didn’t like the idea of it at all. Then she started doing the most beautiful thing. Every morning at 5 a.m., before she made her rounds at St. Vincent’s, she rode her bike to my apartment to check up on me. It was incredible. She organized it so the visiting nurse would give me the I.V. Pentamidine for the PCP pneumonia, and Brian would give me three intramuscular injections of Procrit per week for the anemia. I was still on an I.V. drip of vitamins and pills that would “help” the immune system. I don’t remember what the pills were and I don’t know if I really cared at the time. I had that panic that we all had in the gay community then—to get any medication we heard about which might save our lives.8 It was very Dallas Buyers Club everywhere.

At one point, I developed toxoplasmosis in the brain, which is a parasite.9 I had to take pyrimethamine and sulfonamides to get rid of it. The infection and medication kept me awake constantly. I couldn’t sleep for two or three days at a time. My whole system felt dreadful. I was a nervous wreck. I had so much anxiety. I had no idea what to do with it. I wrote frantically in my journal:

I hate this nervous energy from no sleep.

My handwriting is changing since the pneumonia.

Since the pneumonia I haven’t found a comfortable rhythm to settle into yet—need to find it soon so I don’t go crazy.

These hours I’m keeping are crazy, 5:30 in the morning is too damn early to do anything! Never mind, I’m up and ready to go like it was the fucking army! Yuck!

What to do?

Read.

Write.

God helps us all.

Please.

Silence is not needed.

Wow, that Klonopin tablet sent me into outer space for the evening. That’s good, I guess.

It’s 5 a.m. I took another Klonopin to see how it feels. Dr. Starrett wants me to take 3 a day, which sounds extreme. We’ll see how I feel.

Should I try to sleep more? I’ll give it a try. I want to write a book. The book will be called “Love and Death From the Virus.” Sounds good to me.

I got a good boxing photo from Ira.

I need a new typewriter.

I have a new poem here—“In the Garden.”

It’s 3:20 a.m. and it’s a ridiculous hour to be up, but here I am again. And the smell of bananas repulses me. I’ll never eat a fucking banana again.

I took another Klonopin and I hope to be in dreamland shortly.

Where are people going at 3:30 in the morning?

I’m still not sleeping. I see headlights outside. Street lights. What’s going to become of this sleep pattern?

I need to set up my work table for collage and typing but it’s already put together in my bedroom.

Writing with a better typewriter would help. Get a better typewriter ASAP.

I’m not sleeping from that second Klonopin.

Writing, I never thought so much of it in my life. It will be my salvation.

Saw Matthew Goulet—psychiatrist—thorough, smart, and very handsome. Both doctors want to desensitize me to Bactrim again, also to get a CAT Scan and a spinal tap.

This is hell.

It’s 4:30 in the morning again. I did get 8 hours of sleep. but still. . .

I’m takin Klonopin, I’m writing postcards, I made a tape for Patti

5:30 in the morning!

Where are all of these trucks going? What are they delivering? Deliver me a boy is more like it!

I feel like shit. I hope its temporary.

I’ll go to sleep early and start eating more greens

I Think I Want to Live in a Treehouse.10

The anemia and the toxoplasmosis and the anxiety kept me chained to the sofa. I couldn’t get up to do anything. If I had to get up I could only do it slowly, like I was a very, very old man. I hobbled to the bathroom, and then back to the sofa, and then back to the bathroom, the sofa, the bathroom, the sofa. . . .

There is no curtain in my bedroom window . . . on purpose

My friends all sleep in blackness

Windows practically boarded up

I sleep under the stars with nightlight

From sky and street

When morning arrives

I open my eyes

To see a Magritte sky

Bright, surreal and always moving

This keeps me sane

This keeps me from screaming

It lets me know

That I still have my sight

And that this terrible virus

That has ravaged my body

Has left my eyes alone.

I am the keen observer of truth and beauty.11

Because I couldn’t get up easily and Brian was often out running errands or going on auditions—when the phone rang, he wasn’t around to pick it up for me. I couldn’t get up to answer it myself, so my answering machine recorded whatever calls came in. Some of them were very long and involved. Many were from friends and family, as well as Chris Duffy—my boyfriend at the time, Nina Simone, or Patti Smith.

The medication and the toxoplasmosis were still keeping me crazed. I even called Michael Feinstein in the middle of the night because he was heading to the White House in the morning to perform. I asked him to steal President Clinton’s cat “Socks” when he got there. In fact, I begged him.

“You have to get me that cat! Bring me back Socks!”

He heard me loud and clear, but then tried to talk me down from my late-night mania. And when he came back, all he brought me was a fuckin’ napkin with the White House logo on it. No Socks! No silverware! Nothing! I was furious.

Around this time, Barbara told me about a new medication that the FDA had approved called AZT.12 She said I could take a small amount to see if I could tolerate it, and then take a larger amount later that would, theoretically, help the AIDS symptoms, which were by then exploding.

Burroughs Wellcome . . . tested . . . something called Compound S, a re-made version of the original AZT. When it was thrown into a dish with animal cells infected with HIV, it seemed to block the virus’ activity.13

The problem was that many of the men I knew who were taking AZT were dying or had died from the very drug that was supposed to save them.

Under enormous public pressure, the FDA’s review of AZT was fast tracked . . . [a]fter 16 weeks, Burroughs Wellcome announced that they were stopping the trial because there was strong evidence that the compound appeared to be working.14

Barbara was skeptical about it. But she was willing to give me the AZT if I wanted it.

You will not find a more potent symbol of the complex story of AZT, a story of how the struggle to find a “magic bullet” to help millions of people . . . degenerated into a saga of distrust, confusion, and anger. It is a story of health and illness . . . of scientific ambition, secrecy and political pressure, and of the amounts of money that can be generated when a lethal virus turns into a worldwide epidemic.15

Barbara knew there was something wrong with the drug as she was seeing too many deaths related to it. I think, somewhere in her mind, she believed there would be a new medication soon. I knew how smart she was so I continued doing all the nontraditional things she recommended.

I don’t remember how many months passed that I was incredibly ill, lying on the sofa. There were many times in the middle of the night when Brian had to arrange for a taxi to take me to the hospital. He usually called the gang in my inner circle to help: Debbie Southwood Smith, Carol Friedman, Arturo Vega, Tim Ebneth and Daniel Rey—these marvelous people were, like Brian, selflessly concerned for me. There were nights when Debbie came over to my apartment because I had a fever so high I could barely function. She would wash me down with cool, wet towels and change my sheets and stay with me until the fever broke. Often Arturo and Daniel came by during the day to lift my spirits and sit quietly with me and watch TV. I was constantly on the phone with Carol, and sometimes both Eric Bogosian and Tim Ebneth came over to keep me company and bring me muffins and sweets. I was wasting away and all my friends just wanted to see me healthy again.

Then in the middle of the year, on one of her morning visits, Barbara told me about a number of drugs she had learned about which she believed held real promise. Among them was a Protease inhibitor called Saquinavir, and she urged me to take it. I don’t think it had been approved by the FDA yet,16 but she believed it was the right thing for me to take. She also urged me to take it in combination with a few other drugs, an early form of the “cocktail,” I believe, which ultimately became the primary treatment for HIV patients.

In 1995, a combination drug treatment known as the “AIDS cocktail” was introduced. This type of therapy is now known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). . . . [which] has led to dramatic improvements in people who have used it. People have experienced decreased viral loads (the amount of HIV in their body) and increased counts of CD4 cells (immune cells that are destroyed by HIV). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, people who take antiretroviral therapy as prescribed and maintain an undetectable viral load have “effectively no risk” of transmitting HIV to others.17

I had enormous faith in her. She had accepted that I would not go to the AIDS ward in St. Vincent’s; she supported me by coming every day to check on me at my home; and she had steered me away from AZT. There was no way I wouldn’t follow her recommendation, so I took the medications.

With introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy, AIDS diagnoses and deaths declined substantially from 1995 to 1998 and remained stable from 1999 to 2008 at an average of 38,279 AIDS diagnoses and 17,489 deaths per year, respectively.18

About six months later, I started to feel better. Brian had moved out by that time and taken an apartment on East 27th Street. Around that time, I went over to his place for his thirtieth birthday to celebrate with his family. I did not look my best. I was still thin and gaunt, but I felt strong. My gratitude to Brian is immeasurable. It was hard to understand the kind of selfless gift he gave in being there when I was so close to dying. He was a saint in helping me to recover and to survive, because as I sat there while he blew the candles out on his birthday cake, I felt it coming back. It was all coming back—my strength, my health . . . my life.

Those years, in the early 1980s when AIDS first hit, were a frightening time for all of us. The fear was monstrous in size and it took over the entire community. We were struggling with symptoms that were unimaginably painful and devastating. There was also the uncertainty and threat of medications doctors were trying and hoping to get approved faster than light, to stop this catastrophic plague.

However, there was a feeling—at least in the beginning—that we, the gay community, somehow brought this horrific disease into the world. That belief remained, despite the fact that AIDS was destroying many, and for a time, nearly all of us in that world. Thankfully, that judgment was disproven.

SIVcpz [simian virus] was transferred to humans as a result of chimps being killed and eaten, or their blood getting into cuts or wounds on people in the course of hunting. Normally, the hunter’s body would have fought off SIV, but on a few occasions the virus adapted itself within its new human host and became HIV-1 . . . which is the strain that has spread throughout the world and is responsible for the vast majority of HIV infections today.19

Today, I take a cocktail of medications like every other person with HIV, and I stay healthy. I have safe sex, and I deal in strength and faith, and antivirals, because there is always a tomorrow for me and there is always hope in that tomorrow.

Vito [Russo] gave a speech to ACT-UP in 1988 that would become his boilerplate pep talk. “Someday, the AIDS Crisis will be over,” he would shout to whoops and hollers. “And when that day comes—when that day has come and gone, there’ll be people left alive on this earth—gay people and straight people, men and women, black and white—who will hear the story that once there was a terrible disease in this country and all over the world, and that a brave group of people stood up and fought, and in some cases, gave their lives so that other people might live and be free.20

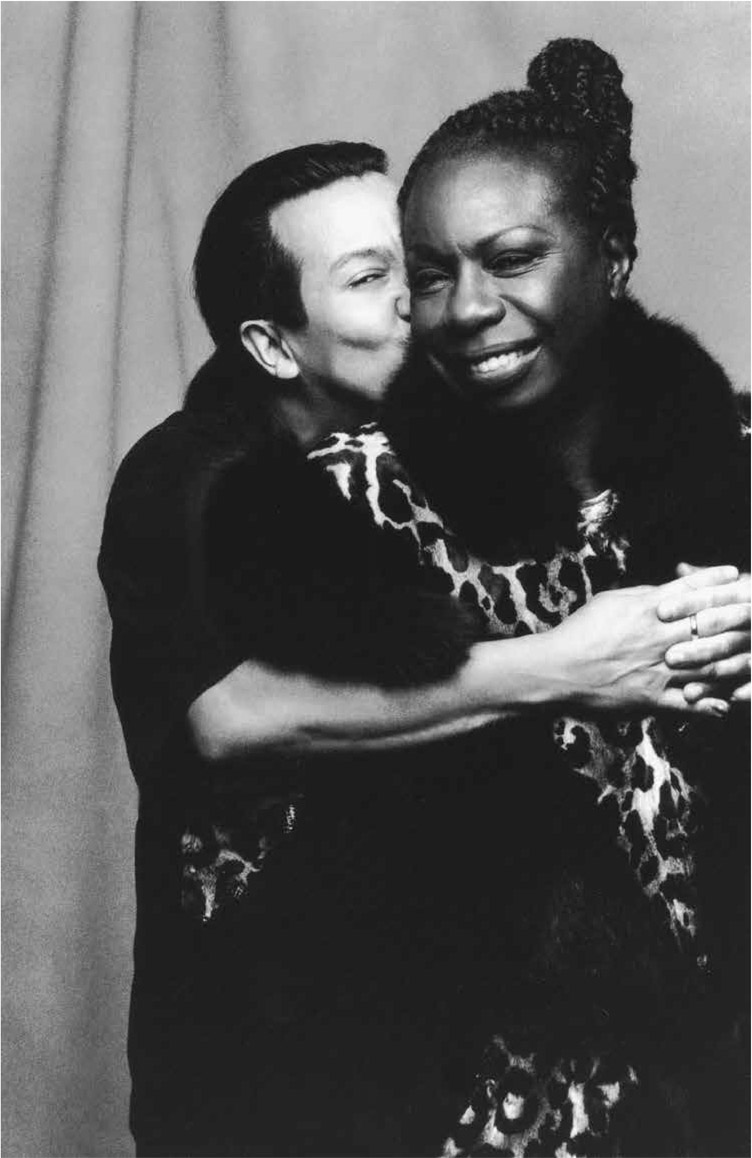

With Nina Simone, 1993. (© Carol Friedman)

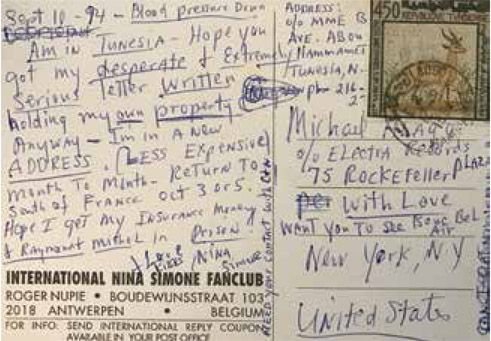

Postcard from Nina Simone, 1994. (Author Collection)

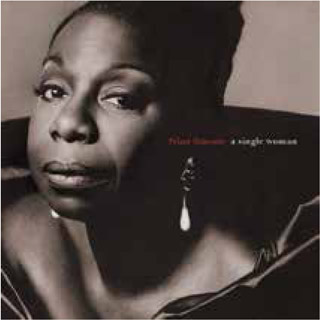

Nina Simone A Single Woman album cover, 1993. (© Carol Friedman)

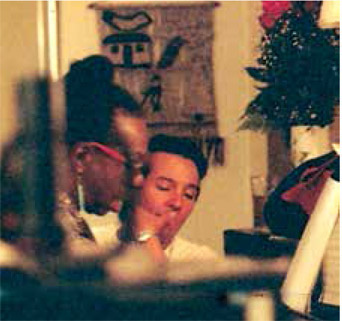

With Nina late night at her apartment in West Hollywood, CA, 1992. (Author Collection)

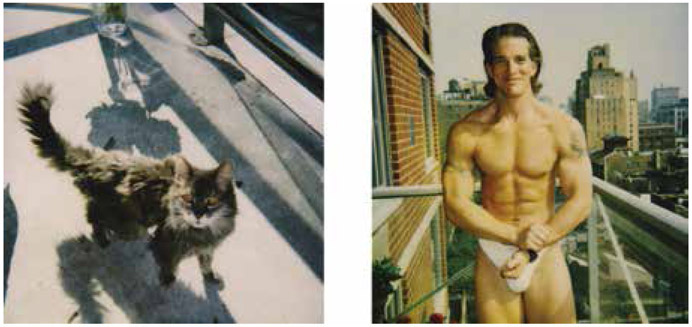

Polaroid collage of Foxy, the meanest 22 yr.-old cat in NY, and my sweet and adorable Brian Regnaert, 1994. (© Michael Alago)

Frank with kittens at Louisiana State Prison, 2017. (Author Collection)

With Jerry Only of the Misfits, 2016. (Author Collection)

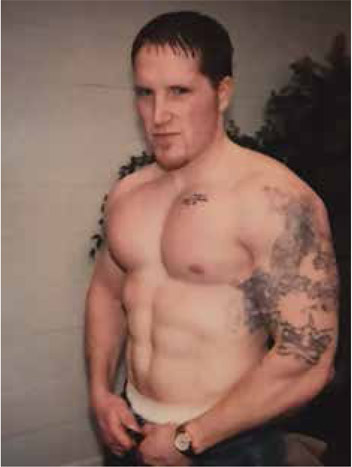

Marty at Airway Heights Corrections Center, Washington State, 2004. (Author Collection)

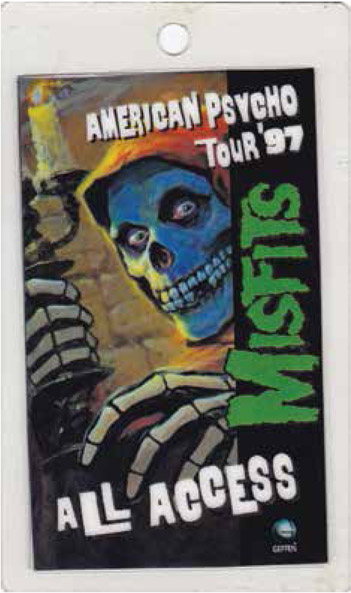

All Access American Psycho Tour laminate, 1997. (Author Collection)

Obey Misfits graffiti, Wynwood, Miami, Florida, 2016. (© Michael Alago)

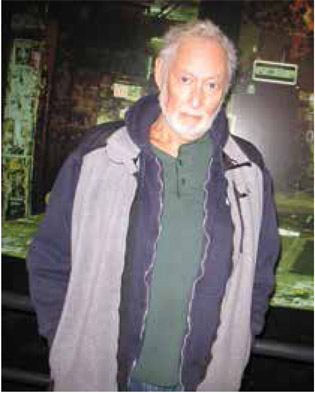

Portrait of Hilly Kristal, New York City, 2006. (© Michael Alago)

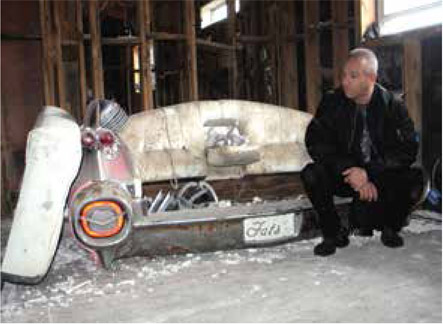

After Hurricane Katrina, Fats Domino’s home, Lower 9th Ward, New Orleans, 2007.

(Author Collection)

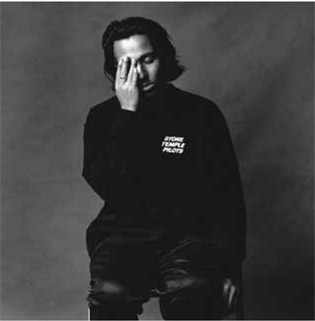

Michael Alago, Studio Portrait, 1993.

(© Stanley Stellar)

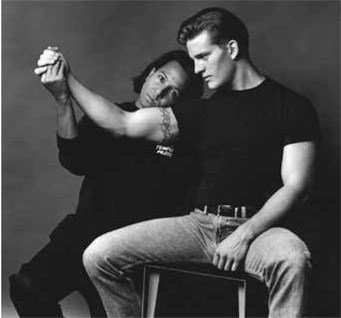

Michael and Brian, 1993.

(© Stanley Stellar)

2018 selfie with Mina Caputo and Carol Friedman. (© Carol Friedman)

With Carol Friedman, 2019.

(© Carol Friedman)

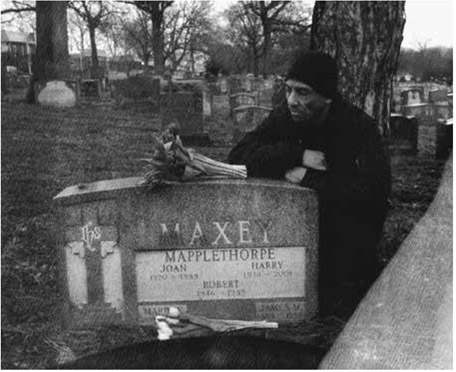

Visiting Robert Mapplethorpe’s grave with Patti Smith, Lenny Kaye, and Edward Mapplethorpe on the 20th anniversary of his death, March, 2009. (Author Collection)

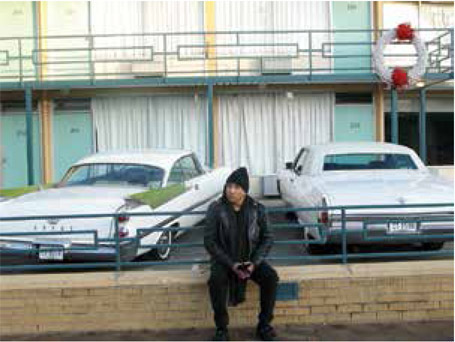

In front of the Lorraine Motel, Memphis, Tennessee, 2010. (Author Collection)

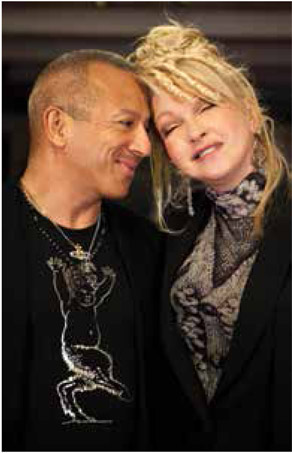

Cyndi Lauper and Jacqueline Smith outside the Lorraine Motel, Memphis, Tennessee, 2010. (Author Collection)

With Jacqueline Smith outside the Lorraine Motel, Memphis, Tennessee, 2010. (Author Collection)

With Cyndi Lauper, on the set of “Who the F**k is that Guy?,” New York City, 2014.

(Photo by helenabxl)

Historic sign showing how long Jacqueline Smith has been standing in protest outside the Lorraine Motel, Memphis, Tennessee, 2010.

(Author Collection)

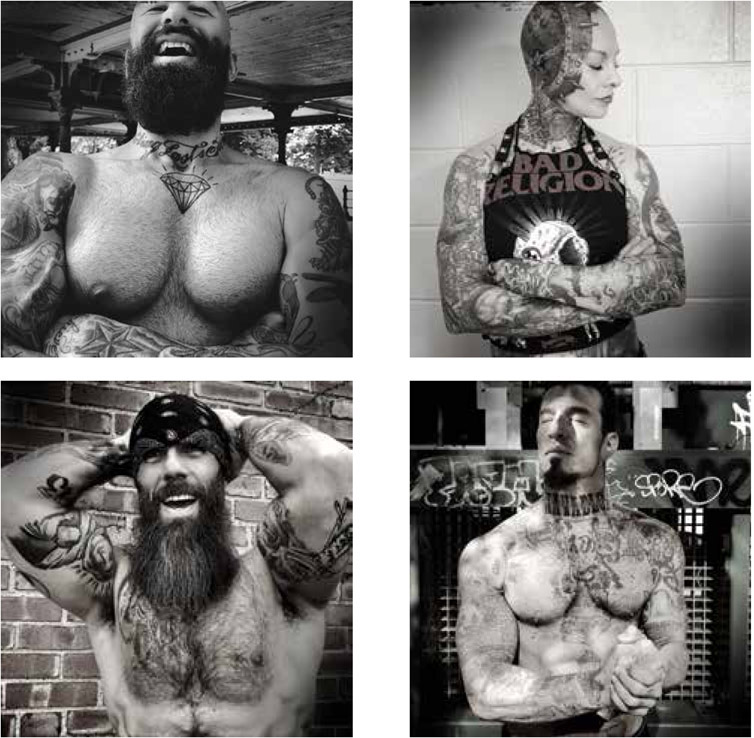

Current portraits shot with The Hipstamatic App., 2017–18. Top Left to Right: Al Kavadlo, Kris Sims, Left to Right Bottom: Thaddeus Jones, Danny Kavadlo. (© Michael Alago)

My mom, Blanche, with her beloved St. Jude Statue, 2016. (Author Collection)

Alago Family Portrait: Cheryl, Mom, and me, 2016. (Author Collection)