Chapter Twenty

Apogee/Perigee

Camp Fredg 24 March ’ 63

My dear brother Carter

I have recd your letter of the 18 th will endeavour to forward the enclosure to Mrs. Taylor. I do not know where she is now. When last at her house on the Rappk the enemy seemed to be preparing to cross very near it. Whether it was a feint or a reality I could not tell, but recommd they should make arrangements to evacuate if necessary & I have heard they proposed going to their country house in the forest. Genl Jackson is quite near me & her residence is not near him. The weather has been very unfavorable to those exposed to it & the roads are nearly impassable. Genl Hooker seems to be prepared for a move somewhere, & this day week the indications were he was coming over. He threw his cavy over Kellys ford & brought his infy to the U.S. ford & just below the mouth of Rapidan, but the former was so roughly handled by your nephew Fitz that it had to retire at night, & the latter stuck to their position.

The reports from within their lines are that the Cavy was to have swept around to the Central & Fredg R R.s. Burn our depots & cut us up generally, under cover of which their infy was to cross, but that we had forestalled them &c & they changed their minds. I presume it will be repeated in some shape the next fine day. As far as I learn Fitz Lee & his Brigade behaved admirably, & though greatly outnumbered stuck to the enemy with a tenacity that could not be shaken off. The report of our scouts north of the Rappk placed their strength at 7000, Stuart does not put it so high. While Fitz did not have with him more than 800. But I grieve over our noble dead! I do not know how I can replace the gallant Pelham. So young so true so brave—Though stricken down in the dawn of manhood his is the glory of duty done! Fitz had his horse shot under him but is safe. The news from the west is favourable & at the south the blow is still impending on Charleston. When it falls it will be heavy, but if we do our duty I trust we shall not be crushed. Through God we shall do great acts & it is He that shall tread down our enemies. Give much love to Sis Lucy, “Mildred & them”—Tell them I wish I could get there. You must take them all out in the fields & raise us quantities of corn. We are in great need both man & beast. Set all the farmers to work. If they do not do better I shall have to call forward our glorious women—I was glad to have seen George in Richmond. He has become a fine boy. Your affecte brother RE Lee1

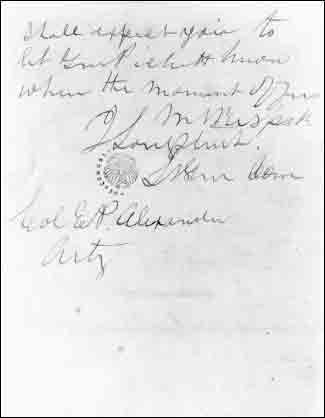

Notes passed between generals Longstreet and Pickett and Colonel Alexander as they prepared for Pickett’s Charge.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

THE NATURE OF HISTORIC DOCUMENTS has fundamentally altered during the last hundred years. Historiography of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries will differ significantly from the way we evaluate evidence from earlier times. Lengthy evocative letters like the ones Lee and his marvelously eloquent soldiers penned are rare now. Our feel for the temporal has also radically changed. Nineteenth-century writers took the time to be expressive; they knew their letters would require time to arrive; and they expected they would be carefully kept as timeless momentos. The invention of photography and sound recording has given us much more immediate information about events and people. Instead of reading descriptions of long-gone scenes, now we can see and assess them for ourselves, play them over and over, hear the tone of voice, watch the response of the crowd. Journal keeping may also have made a reappearance, with bloggers registering their reactions just as spontaneously—if not as secretly—as diarists always have. No one form of communications is superior to any other: who would want to give up the powerfully unself-conscious words of the Civil War private—and, by the same token, who would relinquish the chance to hear Martin Luther King Jr.’s indescribable clarion tones? Each source has its advantages and its flaws. What we often lack in early records is the sense of being personally present at a historic moment, which modern playback culture now affords us. For this reason the documents above are in elegant contrast. One is a particularly nice combination of Lee-the-general’s ability to see around corners in the campaigns of 1863 and Lee-the-brother’s affection for his family—but it is a traditional descriptive account of events. The other group is a rare, nearly real-time depiction of impending tragedy.2 This is a series of notes passed back and forth on the battlefield of Gettysburg between Generals James Longstreet and George Pickett and Colonel E. Porter Alexander as they prepared to launch Pickett’s Charge. Alexander, who had a profound sense of the historic, managed to save them, and taken together they make chilling reading. The notes put us right in the midst of battle, sharing the nervousness, feeling their despair at the waning supplies of ammunition. The anxious give-and-take makes us hope that each notation will halt the attack; yet we are powerless to arrest the flow of history. The doom that hangs on every word sends a shiver through the centuries.

During the frigid winter following the battle of Fredericksburg, Lee kept Jackson in close consultation. They had a new challenger to face. Burnside had been relieved in the aftermath of his “blunder” at Fredericksburg. Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker, a veteran of the Peninsula campaign and the battle at Sharpsburg, was now in command of the Army of the Potomac. Perhaps to offset Lee’s growing aura of invincibility, Hooker took command with great show, declaring that the “Confederate Army is now the legitimate property of the Army of the Potomac. They may as well pack up their haversacks and make for Richmond, and I shall be after them.”3 Actually Hooker was building up his combat effectiveness, and Lee was concerned. He told his wife he wished his forces were not so scattered and that his fodder and provisions were better. He also wired Richmond for the return of Longstreet’s corps, which was on a foraging campaign in southern Virginia. The request was refused. Still, Lee was sanguine of victory and thought if only he could “baffle” the enemy for a few more months, it would demoralize the North into suing for peace.4 Lee was right about his unfavorable position; Hooker had twice his men and a clever plan that sought to envelop Lee’s army with forces coming from several sides simultaneously. By late April Hooker had positioned himself so well upstream that Lee considered retiring to Richmond, if only to protect his supply lines. “The enemy,” Hooker bragged from a crossroads called Chancellorsville, “must either ingloriously fly, or come out from behind his defences and give battle on our own ground where certain destruction awaits him.”5

Lee called his bluff. Leaving only a small force to protect his rear, where he believed Hooker would send one prong of the attack, Lee defied conventional wisdom and struck from a disadvantage, giving battle when Hooker had anticipated retreat. He further offset the numerical discrepancy by fighting ferociously in the area’s scrub woods, where the thick undergrowth gave his men cover. Unfamiliar with the terrain, the Union forces were bewildered and could not effectively use their superior numbers. Lee further handicapped them by taking full advantage of their flawed leadership.6

On the night of May 1–2, Lee and Jackson devised a plan to confound the enemy by splitting their forces and marching the larger portion under Jackson around Hooker’s flank to surprise his rear, while Lee distracted and pinned him down with a smaller force in front. Fitz Lee provided invaluable intelligence that spotted the weakness of Hooker’s entire right side; Jubal Early kept Hooker’s other wing occupied; Stuart protected Jackson’s columns from enemy detection. Jackson’s march and the subsequent Confederate rout of the bluecoats was one of the boldest feats in military history, daring in concept and implementation and requiring immense speed and stealth. It was also a model of synchronization, with each general understanding and expertly playing his part. In the aftermath, Lee was aided by the intervention of a cannonball, which hit a porch column at Hooker’s headquarters, knocking the commanding general senseless. The resulting timidity of Union leadership allowed the rebels to stun their foe, just as Lee had hoped. The following day, fighting on two fronts and seizing on every Yankee weakness, Lee was able to reunite the two halves of his army, capture the most favorable artillery position, then launch a devastating barrage. He pressed the attack until Hooker pulled his men back to their innermost position. The superb maneuvering had allowed the Army of Northern Virginia to move from a defensive position of great vulnerability to a winning tactical offense. “Hooker, the great braggart…has been crushed, ruined and must now give place to some other man,” exalted one of Lee’s soldiers. “Meanwhile our own great Lee continues to grow in the confidence and esteem of our soldiers and people.”7 At the end of the battle, when Lee rode through his men, his fine form silhouetted against the blazing ruins of the Chancellor tavern, he was greeted with the frenzied enthusiasm reserved for history’s great chieftains. “I wish you could have seen and heard the boys cheer him as he rode down our thinned ranks after the battle was over,” a Virginia infantryman exclaimed to his mother. “Even a number of Yankee prisoners were constrained to cheer him so grand and majestic was his appearance.”8

How did Lee realize this extraordinary victory? Like so many dazzling feats, it had as much to do with painstaking decision-making and judicious management as it did with bravura. During the days leading up to the battle Lee expertly sized up the terrain—even making some personal reconnaissance, reminiscent of his Mexican War scouting. He was also assessing the psychological factors that would impel Hooker’s movements. He rightly guessed that the Union commander would not move in a way that would leave Washington vulnerable and that he had little familiarity with the tangled Virginia terrain. He also sensed that his opponent’s confidence might falter when faced with unanticipated, intimidating aggression. Lee capitalized on surprise by assertively fighting when Hooker, believing he had cornered the Army of Northern Virginia, expected an inglorious retreat. And he was directly involved in all aspects of the battle, from planning to leading attacks, a very real presence that stood out in his officers’ minds. In so doing Lee captured the moment and made it his own. He also had his most sympathetic and enterprising generals around him—Jackson, Stuart, Fitz Lee, A. P. Hill—all of whom could be counted on for derring-do. Though he chafed at the absence of Longstreet’s two divisions, the more plodding gait of the Old War Horse might not have been helpful in this fight. Jackson’s twelve-mile march around Hooker’s forces and attack on his right are the stuff of military legend, of course. But the success of the maneuver was due as much to shrewd understanding of the troops’ enthusiasm, utilization of local roads and resources, and the Federals’ susceptibility as it was to glamorous martial tricks. A good deal of ink has been expended in speculating about who originated the brilliant tactic. Jackson’s mapmaker, who is among the most credible sources, implied that it was his chief. Lee later went to rather elaborate efforts to give himself the credit. What is more important is the fact that it showed a near-perfect collaboration in design, timing, and execution between the two men—a symmetry that was missing on too many other occasions among senior leaders in the Army of Northern Virginia.9 Ultimately everything worked at Chancellorsville because it was infinitely prepared and precisely implemented; and because the very audacity of the movements flabbergasted the Yankees and undermined their fighting spirit. That demoralization carried over from this field, leaving a lingering disquiet about what Lee and his army were capable of doing.

General Robert E. Lee in 1863, photographed at the studio of Minnis and Cowell in Richmond.

VIRGINIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Lee’s imposing appearance before the flaming Chancellor tavern was a classic moment, his showpiece, the triumph that more than any other gave him a place among the great generals. The laurels were again won at dreadful cost, however. While attempting to follow up his devastating flank attack on May 2, Stonewall Jackson was accidentally shot by his own men, wounded in the left arm and right hand. The arm was amputated, and it was at first thought that Jackson would recover; but in his weakness he contracted pneumonia and died a week later. Distraught, Lee said he wished it had been him instead of his lieutenant, and told his wife: “Any victory would be dear at such a price.”10 Unfortunately, Jackson’s death was only emblematic of the fearsome toll at Chancellorsville. Despite its success, Lee’s army counted nearly as many killed and wounded as did Hooker. Proportionally it was an appalling loss, by some estimates nearly a quarter of the participating army.11 Listen, as a private and an officer describe the aftershock of such violent death. “I have been on the battle field eight days,” Mississippian John Berryman Crawford wrote, clearly still traumatized:

the sight I saw I cant pen it down it is a slaughter pen it is enough to make old master weep the dead the diying the wounded they was straad for ten lines in ever direction oh what a sight what a sight to behold the loss on boath sides I cant tel but it look like enough to make a wourld.12

A brigadier nearly matched Crawford’s eloquence:

There are periods in every man’s life when all the concentrated sorrow and bitterness of years seem gathered in one short day or night. Such was the case with myself as I lay under an oak the second night, black with smut and smoke, and reckoned the frightful cost of that complete victory and reflected that in less than thirty-six hours one-third of my command had been swept away; one field officer only left for duty out of the thirteen carried into action—the rest all killed or wounded and most of them my warmest friends; my boy brother who had been on my staff, lay dead on the field, and Stonewall Jackson…whom as my general, I then loved, was lying wounded; and probably dying, shot by my own gallant brigade….13

It was hard to question success, of course, but when victory was more elusive, this expenditure of life could seem wanton. From the beginning Lee had determined to use whatever he needed to thwart the enemy. Some had been quickly taken aback at the casualty figures coming out of the Seven Days fight. In just one modest example, an aide to Longstreet was stunned to find that the Palmetto Sharpshooters, a crack unit of 375, had lost 44 killed and 210 wounded.14 Some of Lee’s most loyal officers also questioned his determination to give battle when it could be avoided. Jackson had thought Fredericksburg an expensive, empty exercise, and E. Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s artillerist, believed Antietam was fought “where he had nothing to make & everything to lose—which a general should not do.” Alexander then went on to worry that Lee would provoke another unnecessary bloodletting in the days after Chancellorsville.15 Lee also expressed horror at the high casualty rates and marginal gains, saying that though the public was “wild with delight,” he was depressed after Chancellorsville from the severe loss and the fact that again “we had gained not an inch of ground and the enemy could not be pursued.”16 But he never changed his preference for furious offensive actions, even during 1864, when defensive operations were the more realistic and fruitful option. Lee’s expenditure of life often left his army so weak that he was not able to follow up on an advantage to deal a final blow. It also added to the problems of desertion and straggling, as he began to have a reputation as “a Great Gambler in human life.”17 Some men grew concerned that they were being sacrificed for grand amorphous glory, when other, less costly approaches might be found. Johnston was praised for protecting his men; they were “not allowed to be butchered…to have his name and a battle fought…to go back to Richmond for his own glory.”18 Lee did not view the loss of life frivolously, and he certainly had victory as well as glory in mind as he waged his battles, but the almost unrestrained use of his men seems worth contemplating. If, as he so persistently claimed, his ultimate defeat had been due to the North’s superior numbers, why did he not guard his most precious resource, expending it only when necessary or when he knew he could reap a strategic benefit? Perhaps it was the pulse-raising thrill that he clearly got from his contests; perhaps it was his belief that a knockout blow was needed to quickly end the war.19

Lee felt from the first that the best chance for the Confederacy’s survival was to decisively defeat the Union army, and he held to this belief until the end of the war. “If we can defeat or drive the armies of the enemy from the field, we shall have peace,” he would write. “All our efforts & energies should be devoted to that object.”20 The idea of achieving victory through the annihilation of an opponent’s armed forces rather than conquering territory was an old one. During the American Revolution it influenced Washington and others, who chose to cede key locations but keep their armies intact, and was also advocated by military theorists who had fought with Napoleon. Lee believed that quick, crippling victories would so devastate northern morale that the will to oppose the South would collapse. He also responded to southern public opinion that soared on news of big victories, bolstering popular support in spite of the increasing difficulties of daily life. As a result he continued to seek aggressive action, always hoping for a chance to “entirely break up,” “suppress,” or “ruin” the Federal forces. From Lee’s perspective each battle might be decisive; therefore each required maximum resources and unconstrained effort if it would be the determinant encounter.

Practically, however, the changed military technology of the Civil War era made it difficult to actually destroy an army through the large-scale field operations he preferred: as one historian observed, Lee and his generals “won the kind of battles which were not to decide this kind of war.”21 Improved transportation allowed for rapid resupply, directional change, and regrouping of forces. More flexible unit and command structures, also pioneered by Napoleon, allowed generals to change fronts and mass troops more effectively. The use of accurate, long-range rifled muskets and artillery meant that infantry was rarely overwhelmed by cavalry attacks, and indeed, if well entrenched, was largely impervious to frontal assaults of any kind.22 Lee had experienced firsthand the defensive advantage at Fredericksburg, and was certainly abreast of current military technology, yet he actually became more vocal about his desire for a crushing, definitive blow as the war progressed. In 1864, when slow erosion by partisan operations might well have sapped northern esprit prior to the critical presidential election, and the Confederate public was willing to accept a more defensive posture, Lee was still openly insisting that his men must “strike them a blow!” or “unite upon [the Army of the Potomac] and endeavor to crush it.”23

It was with this mindset that Lee determined to move north again after Chancellorsville. The public was jubilant, and he was frustrated and anxious to finish the job. Moreover, the Army of Northern Virginia was at the pinnacle of self-assurance, believing itself fully equal to anything it might encounter and nearly unbeatable under Lee’s leadership. “We looked forward to victory under him as confidently as to successive sunrises,” recalled one officer.24 Lee convinced Davis that the moment was propitious for reinvasion, and Secretary of War James A. Seddon reluctantly gave up his opposition, though he was later to regret it greatly. But given the lessons of the previous year’s Maryland campaign, they were now more hesitant about the prospects for a northern incursion. The timing was also unfortunate, since it was a critical moment at Vicksburg and they had actually thought to borrow a piece of Lee’s army for western support. Lee finessed the power structure in Richmond, retained his troops and his political backing, but failed to get additional forces for the invasion. “A far as I can judge there is nothing to be gained by this army remaining quietly on the defensive,” he told Seddon, adding that he believed unless the Army of the Potomac could be drawn away from northern Virginia it would simply wait, regain strength, and concentrate for an attack.25 For a time it all seemed to go as smoothly as Lee had planned. He and his men crossed the Potomac without incident, to the dismay of Lincoln and skeptical northern editorialists. The Confederates’ unchallenged tramp through southeastern Pennsylvania also resurrected talk of diplomatic recognition by foreign governments, and in parlors from Paris to Pittsburgh everybody waited to see just what Lee’s actions would bring.26

There is no leader who proceeds without a misstep, but the timing and nature of that misstep can have great consequence. In the Gettysburg campaign the unsure footing of northern soil was complicated by innate risk—in numbers, in intelligence, in political support. There were those who wished Lee’s magnificent army would remain on the alert before Richmond, and saw no reason to provoke the powers at Washington to greater energy and determination. Lee had bet on the flip side of this coin—Union demoralization and fatigue—in which there was some validity. Lee went into Pennsylvania, as he had Maryland, to meet the enemy on his soil, to beat him there in a show of will and superior skill, and thereby to consign him to defeat. He glossed over this objective in his later years, stating that he wanted just to forage, to draw his opponent out of Virginia, to “baffle and break up their plans,” denying any intention to take offensive actions except to defend himself.27 But more than one senior officer wrote a contemporary description of Lee’s plan for a battle that would “come off near Frederick City or Gettysburg,” and Lee even candidly told Jefferson Davis that his idea was to lure the enemy “out into a position to be assailed.”28

Unfortunately, he was obstinately clinging to an old structural design, one that had proven to be unstable the previous year—and that was something his engineer’s education had taught him not to do. Once north of the Potomac he encountered much the same atmosphere he had in Maryland. He made another gesture toward peace with the local population, but found, in the words of one of his men, their “hostility to us is strong & open & [they] are furious at the invasion.”29 The ambience was not enhanced by the extensive official foraging that was done by his army. Lee had sent round orders, commanding his men to exhibit their superior civility by refraining from poaching on the local population. The orders were tacitly ignored by many unit commanders, “who paid not more attention to them than they would to the cries of a screech owl.”30 At least one of Lee’s senior generals, Lafayette McLaws, thought the nonpillaging policy was actually unfortunate since the men were hungry to avenge the devastation at home and the Federals gave way any time their adversaries “even threatened retaliation.”31 The regulations required that Confederate currency or vouchers be exchanged for food or animals, but these were unredeemable in Pennsylvania and, indeed, nearly worthless in points south. The policy resulted in such scenes as Lieutenant John Hampden Chamberlayne entering a Sunday-morning church service, holding the congregation at gunpoint, and distributing vouchers while his men appropriated all the horses tethered in the churchyard.32 Overall there was little direct violence against civilians, but plenty of chickens went missing.

Worse was the sight of Confederates kidnapping blacks who lived in the vicinity. It appears that several hundred African-Americans were dragged from their homes, and some sold again into slavery. According to witnesses, small children were roped to the front of rebel wagons and “driven just like we would drive cattle,” sometimes guarded by the company chaplain. This was not a set of random acts, but a willful policy of abduction. Infuriated at the Yankee destruction of Southern property, and alarmed and insulted by the induction of African-Americans into the Union army, the Confederate Congress passed a proclamation in May 1863 that authorized Jefferson Davis to take “full and ample” retaliatory measures, including the apprehension of free black people and their return to the slave states. The policy showed a deep-seated need to demonstrate the continuity of slaveholding culture, and denial that the Emancipation Proclamation, or any other aspect of the two-year war, had altered the fundamental right to own human property. Evidence links virtually every infantry and cavalry unit in Lee’s army with the activity, under the supervision of senior officers. “I do not think our Generals intend[ed] to invade except to get some of our Negros back which the Yankees have stolen and to let them know something about the war,” noted one of Jubal Early’s sergeants. Longstreet reminded his division commander, George Pickett, that “the captured contraband had better be brought along with you for further disposition.” General Robert E. Rodes was said to have personally threatened to burn down a town after its citizens tried to rescue one convoy of captured African-Americans. Since the activity was so widespread, Lee must have known of the abductions and condoned them, though in general he had tried to stay away from retaliatory policies, which he thought counterproductive.33 None of this was conducive to either amity or capitulation on the part of the North. One of Lee’s major miscalculations on this trip into Federal Territory, as on his previous excursion, was the belief that the presence of his army would deflate the Union’s will to defend itself, rather than prod it into self-protection. “Lee is playing a bold and desperate game…,” warned a soldier in the Army of the Potomac, “Lee’s advance northward may prove the advance of his army to capture or destruction.”34

A first principle of engineering is to build on accumulated knowledge: to guide a project by experience and base innovation on solid past precedent. Lee had already ignored this scientific training when he copied a campaign that had previously failed. Throughout the excursion into Pennsylvania he seemed to leave behind the precise mental tools of an engineer. It is doubtful that Lee could have wandered for long north of the Mason-Dixon line without being challenged in the field, yet he left his supply lines behind, which precluded remaining for a prolonged time in any one spot. Although situated at the hub of five roads that made for ease of reinforcement, geographically Gettysburg was a difficult spot for the kind of aggressive actions he preferred. The town was located between creviced ridges and boulder-strewn hills, the geological aftermath of retreating glaciers. George Meade, who was put in charge of the Army of the Potomac in late June, was himself a first-rate engineer; he had sent his most trusted subordinates to scope out the area and wanted to avoid battle there.35

It was also an awkward time operationally for Lee’s army to execute any highly coordinated or delicate maneuvers. Jackson’s death was a serious blow to the Army of Northern Virginia. Despite their differences, Lee and Jackson had viewed operations from a similar perspective, and Lee had come to regard Stonewall’s corps as the most reliable at his command. Lee had reorganized after Chancellorsville, carving three corps out of the original two, and placing Longstreet, A. P. Hill, and Richard Ewell in charge. Longstreet was greatly experienced, but the others were new to the job, which involved considerably more managerial expertise and strategic judgment than their previous division assignments. An essential part of a top commander’s job is to ensure a smooth transition during such personnel changes, but there seems to have been little priority given to coordinating the new team, or managing weak points, like Ewell’s indecision or Hill’s fitful aggression. Stuart was off harassing Yankee supply lines to the west, following discretionary orders from Lee to do just that. Lee, a stickler for precise information, was handicapped by his absence, and indeed seems not to have known exactly where Stuart was. As a result, Lee entered the battlefield without knowing the landscape, the size of the Union’s force, or the ability of his top generals to perform under pressure. As questioning James Longstreet would write: “The army…moved forward, as a man might walk over strange ground with his eyes shut.”36

Gettysburg could have been a successful one-day contest for Lee, before positions were drawn and while the Confederates outnumbered the Yankees. In fact, on July 1, when advance troops from A. P. Hill’s corps unexpectedly met two brigades of Union cavalry, they opened the contest with a near rout of the bluecoats. General John Reynolds, one of the most highly esteemed corps commanders in the Federal army, fell in defense of his native Pennsylvania, and the Northerners were driven through the town, with more than 4,000 taken prisoner. “It was a terrible battle yesterday,” wrote a Union officer from the field. “We were completely overwhelmed by superiority in numbers, were flanked by the enemy, exposed to an enfilade fire, and it looked as if we would all be ‘bagged.’”37 The only bright spot for the Northerners was the shrewd fallback arrangement they had made to regroup on Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Ridge, high ground southeast of the town. Meade’s engineers had done a reconnaissance of the area and determined that the ridges, which offered superb visibility and abundant natural cover, were strongly defensible. Confederates later regretted that Lee did not recognize this sooner and take the positions early in the battle, when “it would have been a comparatively easy matter…to have brought more troops into action…and captured the key-point of the position.”38 By the time Lee directed Ewell’s corps to take Culp’s Hill “if practicable” on the evening of July 1, the commanding general felt he could not spare additional men to buttress the assault. Ewell, receiving mixed signals—a conditional order without the support he needed to carry it through—called off the attack as night fell. Some of the top men, notably Longstreet, warned Lee that the enemy’s position was “very formidable” and would likely be reinforced during the night, and that to continue an attack at that spot would have a questionable outcome. Longstreet believed that the Army of Northern Virginia should do a flank march around the Federal troops, placing itself between Meade and Washington. He thought Meade would be forced to attack, which would give the rebels the advantage of a strategic defensive position. Others thought the Southerners should at least outwait Meade and see if he either retreated or launched an assault, which could be defended from their position on another piece of high ground, Seminary Ridge.39

To Longstreet’s intense dismay, Lee did not accept the advice. “If the enemy is there to-morrow,” he insisted, “we must attack him.” Later that night Longstreet’s concerns were reiterated by all of Lee’s other senior men. Longstreet would attest that Lee seemed in a state of controlled excitement, which often characterized him when “the hunt was up,” and was unmovable as to his plan. Why this was so has never been fully explained. Lee later hinted at the difficulties of withdrawal from the field, and foraging in that vicinity, now a necessity with his supply lines cut.40 Fresh from the day’s unqualified victory, confidence in his forces was high. He may also have shared his men’s open disdain for the fighting ability of the Union army and assumed they would be beaten.41 But the explanation seems to lie more in Lee’s character than in military logic. In his wartime experiences he had always liked to make opportunities rather than be forced into a responsive posture. He also had a tendency to overreach, to push himself and those around him to fulfill nearly unachievable expectations, whether it was hurling himself across the inky Pedregal or demanding that his untalented daughters learn to sing. Cartographer Jedediah Hotchkiss heard him give this explanation a few weeks after the events: “He said our army had not been defeated, but had been asked to do an impossible thing and had not done it.”42 There is also another trait that appears to have come into play. Lee could be stubborn as a bulldog when he had determined to do something. A line from a letter penned many years before, when he was courting his wife, seems apt as the drama of Gettysburg unfolds. Writing about setting their wedding date, Lee insisted: “But if you do fix it, do not change it. For I am so in the habit of considering an event that I have once determined upon as done,& want so readily for its accomplishment, that it is sometimes hard to recall me, & worse, to efface the effects of my commencement.”43

On July 2, Lee hoped for an early coordinated attack by Ewell’s forces at Culp’s Hill and Longstreet’s on the Union left that would split the northern defenses. Mixed orders and willful foot-dragging from his unenthusiastic generals meant that he was never able to get the creative, forceful cooperation he desired. Longstreet, whom Lee put in charge of the primary assault, despite knowing of his reluctance, has generally been blamed for tardiness, which kept his men off the field until late afternoon and foiled the plan. Yet a rebel officer attested that “about noon I remember that Lee and Longstreet rode up together and sat for half an hour on the very spot where my guns opened up the fight at 4 P.M. and at that time the infantry was [with]in a quarter of a mile of the position where they began fighting…and I have never understood why, if General Lee wanted the fight to begin, what delayed it then. Surely he could have begun it if he so desired.”44 Meanwhile Lee was donating precious hours to the Federal cause—just at a point when, as one southern officer noted, “Time, it seemed to us, was everything.”45

While Lee was trying to push his men forward, Meade was carefully engineering his defense. The Union army had been reinforced strongly during the night. Meade arranged his troops in an ingenious fishhook-shaped formation that covered weak spots in the line, and allowed for quick support from the inward curve of the “hook” should it be needed. His chief engineer, General Gouverneur Warren, rode out along the ridge and reported back that although strong for defense, it was not an appropriate field to launch an attack. In consultation with his corps leaders the Union commander determined to await movement from Lee. In addition, he recognized that one key to his success would be retaining command of the impressive natural fortifications—Culp’s and Cemetery Hills, and Little Round Top, a scraggy, rocky promontory that proved critical to dominating the field. Southern troops had also surveyed the little mountain, but recognized its importance too late, for minutes earlier Warren had ordered its reinforcement.46

The blue-clad men battled valiantly to protect these positions. Over the next two days, the Confederate army would learn just how badly it had misgauged its adversary’s capabilities. “The Army of the Potomac was no band of school girls,” as one Yankee would drily put it.47 Southern scorn of the Union men had never been really justified; the Army of the Potomac had generally fought bravely, the more so since their top command rarely did them credit. At Culp’s Hill, they showed their mettle by staving off a near victory for the South. Using well-designed entrenchments that multiplied the effect of their force by three, the Yankees held the ground even when some of their comrades were siphoned off to meet Longstreet’s offensive, as Lee had calculated. The famous contest over Little Round Top, fought in some places with bayonets, was won for the Union by sheer grit.48 Though the southern forces came within yards of dislodging the Yankees, and ended the day with the taste of victory still in their mouths, the Federals had retained control of every advantageous position on the field.

On the night of July 2, Meade felt confident enough to hold a council of war and obtain concurrence from his commanders to remain on the field; Lee again faced serious dissent among his generals for continuing his assault. Meade, still in scientific mode, planned no attack, but recognized that his strength lay in his superior defensive position. Since the Confederates had failed on July 2 to break his line on either side, or, in the words of Lee’s aide, “to drive the Yankees from their Gibraltar,” Meade anticipated Lee would try a massive assault, probably on the center.49 Officers under him, who had recently clashed with the irrepressible J. E. B. Stuart at Brandy Station, believed also that Lee would try to ride round the Federal army to attack vulnerable points on the flank or in the rear. Recognizing the formula that had proven so devastating at Manassas and Chancellorsville, this time the Union Army was forearmed, dispatching a cavalry force on the roads that curved round the right of the fishhook to open ground behind Meade’s guns.50

Meade also borrowed Lee’s tactics of deception. The Union guns joined a cacophonous two-hour artillery battle in the early afternoon of July 3, the greatest of the war, but ended their fire before the ammunition was spent, giving the impression of capitulation.51 Fooled, Lee ordered two of A. P. Hill’s divisions to join George Pickett’s men in a three-quarter-mile march across open fields and into the massive force of the supposedly damaged Federal army. Then Meade unexpectedly renewed the fiery storm, mowing down the lines, to the horrified awe of those watching. As Longstreet and Alexander’s urgent battlefield notes tell us, the Confederates had nearly run out of artillery shot and were unable to provide cover for their men. In addition, their officers were uncoordinated: General Lewis Armistead’s brigade, for example, should have reinforced the units on his right, but “owing to mismanagement” was out of position and advanced in the wrong direction, into the “mingled mass” of the center lines. A few of the 12,500 rebels reached the Federal lines, but more than half were slaughtered, including two-thirds of Pickett’s division. Leaderless and terrified, those remaining broke ranks and retreated in disarray. From the top of Little Round Top the Union boys “sat on the rocks and laughed at them.”52

Confederate officers, including Lee, tried to encase it all in nobility: courageous men launching themselves into the forces of an oppressive power, charging with unflinching valor into superior fire. It was a scene, as one rebel wrote, “that will be the theme of the poet, painter and historian of all ages.”53 Yet a participant in the charge recorded something different that day, as he sat next to a friend whose skull had been blown apart, and gazed on comrades who were “actually fainting” from dread. “I tell you there is no romance in making one of these charges…. I tell you the enthusiasm of ardent breasts in many cases ain’t there,” he soberly testified. “Virginia’s bravest noblest sons have perished here today and perished all in vain!”54 Lee appears to have again ignored the overall management of his battle, dismissing the counsel of his generals; unaware that his side really was out of ammunition; failing to firmly press some of his orders; forcing through others, even when his own countenance “did not look as bright as tho’ he were certain of success.”55

There is, at least, compelling evidence that Pickett’s charge was not the foolhardy throwback to eighteenth-century assault tactics it sometimes appears, but part of a larger plan, which Meade’s men thwarted. Lee seems to have decided to follow his winning pattern of attacking on several fronts. Pickett’s showy advance was to be made in tandem with cavalry action to the Union rear, while Ewell again assailed Culp’s Hill. After seven hours of brutal fighting, however, Ewell’s men were beaten back from their trenches by the reinforced Federal 12th Corps, ending Lee’s chances to pierce Meade’s right line while assaulting his center.56 In the meantime, J. E. B. Stuart, who had finally rejoined Lee on July 2, was sent with all available horse units to ride around the fishhook with orders to launch an unexpected, debilitating strike at the rear, which would compel the Yankees to fight on multiple fronts. But Stuart’s horsemen were anticipated by three Union cavalry brigades, one led by George Armstrong Custer, who had days before been brevetted from first lieutenant to brigadier general. On July 3 he earned his promotion. Surprised by the interception, Stuart made a desperate charge, which turned into a vicious revolver-and-saber contest between dismounted units. Persuading forces in the vicinity to join him, and rallying the 1st Michigan Cavalry with cries of “Come on you Wolverines!” Custer’s improvised unit held the ground until they were reinforced, fighting with an intensity that matched their comrades on Little Round Top.57 Despite inferior numbers, they foiled Stuart’s intentions, allowing the Federal army to concentrate all of its power against the awful procession of Pickett’s exposed men.

“I still think that if things had worked together [victory] would have been accomplished,” Lee sadly told Jefferson Davis a few weeks later. His strategy might have succeeded had he built it on a less boggy foundation. The Union’s ability to fight with boldness and heart had been laughingly dismissed, and Lee’s penchant for secrecy excluded his chief officers, who understandably failed to coordinate on a battle plan about which they knew nothing.58 As night fell, this time the Union boys had an opportunity to cheer. “The wave has rolled upon the rock,” wrote one Yankee, “and the rock has smashed it. Let us shout too!”59

It was an awful hour for Lee, seeing his troops slashed and panicked: the remnants of regiments, the sole survivors of once-proud companies, all running rearward to Confederate lines.60 The sight seems to have jolted him back into his inspiring generalship. It was perhaps his most terrible moment, but also among his most magnanimous. A witness called Lee’s presence “sublime” as he rode among the men, calming them, his face showing nothing but encouragement, his voice even and cheerful. “All this will come right in the end; we’ll talk it over afterwards; but in the meantime all good men must rally,” he told them. To a devastated brigade commander he intoned, “Never mind, general, never mind. It is all my fault, and you young men must help me out the best you can.”61 The following day he made plans for a retreat, and led his men through one of their worst ordeals—a race against the Union’s menacing pursuit, in torrential rains and amid the screams of the wounded, who accompanied them by the wagon-load. The men had eaten nothing for days; the commanders fished dead horses from the river to salvage their shoes. Yankee skirmishers knocked off men and horses with stones and gun butts. His dexterity reestablished, Lee then accomplished a master feat: conducting his army across the swollen Potomac with great skill, saving them from near destruction at the hands of the Federals.62 The army returned to northern Virginia, and Lee continued to take the blame for Gettysburg, publicly and privately. He wrote disjointed, mistake-strewn notes to his family, and letters of resignation to Jefferson Davis.63 The Confederate president, unable to afford the loss of this general, dismissed them, and rode with him through Richmond. No one cheered. The next day Lee suffered what appears to have been a coronary-related attack.64

Confederate dead at Gettysburg, photographed by Alexander Gardner.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Though it is widely seen as the turning point of the Civil War, Gettysburg was not the decisive battle. The conflict continued for twenty-one months after this date, even though Vicksburg had also fallen to the Union on July 4. The most devastating encounters were still to come. The battles of spring 1864, with Grant’s steamroller determination and the exhaustion of the Confederacy, would prove more conclusive.65 Nor did the Army of Northern Virginia think itself vanquished. Morale suffered, and the men accepted the situation as a major setback, but Lee did a laudable job of bolstering their hope and recovery. “The truth about Gettysburg,” judged a graycoat, “is that we were repulsed at the final position of the enemy, & that the want of success was a terrible calamity but we were not defeated.”66 In the North, though victory was loudly proclaimed, neither Lee nor his army completely lost their mystique. “That rebel army fights so hard that every time it is touched it is like touching a hot iron,” complained General Montgomery Meigs. “Whoever touches it gets hurt.”67 Seven months later the U.S. general in chief, Henry Halleck, remarked that only a monumental legion could defeat Lee.68

What went wrong for the South at Gettysburg? It was not superior numbers, for the contest was one of the most equally balanced in the eastern theater.69 Nor was it a want of courage among the rebels, who fought as gallantly as ever. Richard Ewell is said to have confessed that “it took a dozen blunders to lose Gettysburg, and he had committed a good many of them.”70 Lee’s generals have traditionally been blamed for the failure, and to be sure, there was considerable inadequacy among them, although through the prism of hindsight much of their reluctance may have shown good sense. Lee later remarked that the battle would have been won if Jackson had been there. But at the time he knew he had lost that card and must play with the hand he held.71 Ultimately it was up to Lee to maximize his situation; to direct the strategic flow of his forces; to massage here, and admonish there; to make certain not only that his commands were carried out, but that they were understood, and that resources were provided to do so. That, in essence, is the role of the commanding general.72 Absent was the discerning touch he needed to finesse details, foster communication, and win support for his plans. Lee’s justifiable pride in his army was also leaning dangerously toward hubris, so often a harbinger of defeat. “The truth is we had too much confidence,” is how one of his men assessed the situation. “Had we been more cautious and circumspect, the result might have been different.”73 Another fundamental error in Lee’s strategy is that it presupposed a collapse of northern morale in the face of Confederate invasion, rather than a fierce resistance to it. Far from demoralizing the Yankees, Lee’s invasion energized them to protect their territory and their homes—the very taproot of military spirit. “Men will not fight with so much good will in the Enemys own country as they will in their own,” one Virginian concluded after the battle. A Georgian concurred: “I think they fight harder in their own Country, than they do in Virginia, I had rather to fight them in Virginia then here.”74 One can imagine that had Lee actually won at Gettysburg, the protective impulse would only have been strengthened. It may have brought about a swifter end to the war, galvanizing Union will to resist him, quickly marshaling the resources he always feared would be brought to bear. Against this he might easily have been trapped away from his sources of supply, for despite the heady expectations of some of Lee’s staff, he had no ability to occupy Union territory or besiege major cities.75 Moreover, by 1863 the political stakes had changed. Debate was still sharp in the North about war aims and gains; but after the Emancipation Proclamation there was little possibility of a negotiation that might either award the South independence or return the nation to the status quo ante. Nor did the invasion diminish the Union’s ability to fight in the west. Not one soldier was transferred to the eastern theater as Lee marched through Pennsylvania, and the Union captured an important victory at Vicksburg just as Gettysburg was won. On the field, Lee’s judgment was equally problematical. He undervalued territory and timing; he was either overbearing or undersupportive with those who had to carry out his ideas; and he provided neither the blueprint nor the resources to complete his vision. In simple terms, at Gettysburg Lee was out-engineered, outgeneraled, and out-fought.

How then are we to assess the famous military prowess of Robert E. Lee? There were sublime moments—and not all of them were delivered at the hands of inferior generals. He stands out for his daring, physical and intellectual, which challenged his opponents into near intimidation. When he allowed his rational training to supersede instinct he was capable of devising some of the most ingenious tactical plans in the history of warfare. Lee’s sway over his troops is unsurpassed in military annals. Yet he never resolved the fundamental difficulty facing him—that is, manpower and matériel—and indeed on many occasions he reacted as if these resources were unlimited. In terms of grand strategy, more questions must be asked. His forays into the North were not only operationally unsuccessful, but politically naive. His penchant for aggression, attack, and the near-impossible annihilation of the Union army may have cost him the war. Many believe that had he remained on the defensive, which the technology of the day favored, he could have conserved his scarce resources and outlasted the ennui of the Yankees. Extended guerilla-type warfare, so admirably executed by his father during the struggle for independence, was another option. It has been the classic tool of revolutionaries for centuries, and in terrain and temperament the South was well suited to it—if the tenacity of the populace could be tapped. Loyal E. Porter Alexander was among those who came to believe this would have been the most fruitful approach. “We could not hope to conquer her,” he wrote of the Union. “Our one chance was to wear her down.”76 Twentieth-and twenty-first-century Americans will appreciate how quickly superior strength can be sapped by unremitting, targeted, and occasionally heinous attacks against a supposedly unbeatable power.77 But all of this carries us into the “what-ifs” and the “if-onlys” that sometimes threaten to make Civil War history a kind of science fiction. Let us allow Lee to set the benchmark for fine generalship. In 1847 he wrote a letter to his friend Jack Mackay, exuberantly describing the qualities he admired in Winfield Scott. “Our Genl. is our great reliance…,” he told Mackay. “Never turns from his object. Confident in his powers & resources, his judgment is as sound as his heart is bold and daring. Careful of his men, he never exposes them but for a worthy object & then gives them the advantage of every circumstance in his power.”78 Later, he added to this the importance of “producing effective results.”79 We can only guess how Lee measured himself against these standards.