The courtroom on the Dryad and the battle in Zanzibar harbour

TWO SCENES FROM APRIL 1869 characterise some of the extremes of the squadron’s anti-slave trade work, while conforming to the personalities of the two captains that they feature. Philip Colomb was performing scrupulous examinations of dhow crews in order to condemn or absolve the ships he snared. If he were to condemn a ship he sought a watertight case however laborious the process. Edward Meara, on the other hand, ordered an assault on a slave ship, rifles flashing. Meara himself was some distance away from the fight; by ancient custom the captain let his lieutenant lead the mission in the hopes that he would win garlands and promotion. But as ever in this campaign, violence seemed to hover closest to Meara.

HMS Dryad, north-east Arabian coast, April 1869

Night-time, and Dryad was anchored in her hiding spot behind the peak off Ras Madraka. Philip Colomb was playing whist with his three senior officers in his great cabin. He played poorly, letting down his partner while his attention wandered to his hunting. He rose, left his lieutenants to the game, exited his cabin and climbed the steps to the poop above it where he found the seaman assigned to watch the sea space between the island and the mainland. The moon illuminated the sea, the island and the peak above the ship. The wind was light but told of the maturing youth of the south-west monsoon. He had with him his night glass and spotted the boats in their places near the small island.

‘A fine clear night,’ to the officer of the watch.

He had begun to head back to his cabin to take more punishment at whist when something on the island drew his attention: a white tent … a white tent that moved slowly to the left. No, a sail. Then another, and another.

‘Signal the boats. Quick, now.’

The signalman hurried to parcel out gunpowder in little piles so that it would ignite in flashes. Lighting them, five dazzling bursts, the signal was made to the boats in the distance.

Now Philip Colomb counted eight dhows passing beyond the island. For all we know every one of them might be running a full cargo of slaves.

The boats lurking under the island were moving off almost instantly after the flashes. More boats from the Dryad were being lowered and manned within moments. Frederick Brown, the Dryad’s chief engineer, was soon at Colomb’s elbow, reporting that he had already warned his division below to be prepared to raise steam. Living coals were already banked in the boiler room, ready to be pulled under the boilers, awoken, and spurred to whip up a greater flame.

The engineer did not have to wait long for the order. ‘Draw the fires forward and up steam as fast as you can.’

Brown darted off and soon the sound of shovels biting into the great hoards of coal echoed sharply up from the stoke hole.

‘Hands, up anchor!’

In time, far out at sea before the Dryad, Philip Colomb saw flashes: the pinnace’s gun. More flashes: rifle fire. Shots across bows.

Colomb imagined what was going through the minds of the dhows’ crews. Did they imagine pirates? Murderous rivals? They must have been bewildered, at least. The question of whether to heave to or to run. When Dryad arrived on the scene in under an hour, Colomb guessed it settled the minds of the dhows’ captains. This was not rapine or murder but, as Colomb imagined them thinking, only those eccentric Englishmen slave-hunting again. The dhows, seven in total, surrendered, the coordination between Dryad and her boats a success, even in the dark.

Dryad and her boat fleet laboured for the next two hours against a strengthening monsoon current to tow the dhows back to the shelter under the peak. It was well after midnight before all was quiet again. Inspection would have to wait for the light of dawn.

The prayers of the Muslim faithful on the dhows greeted dawn. Not long after, Philip Colomb read Christian prayers to his assembled men, though they were far from all Christian.

Then Colomb assembled a little courtroom, taking a seat at the round table in the centre of his great cabin, flanked by his two senior lieutenants. Saleh bin Moosa stood by as interpreter, adopting an uncharacteristically grave face.

Bin Moosa began ushering the dhow captains in one by one from the quarterdeck, and so the long day began. Questions about the dhows’ owners, origins, routes, cargo; a search for inconsistencies, deceptions. Colomb conducted close inspections of papers, too. By the light of day, it was clear none were slavers on any significant scale. Some of the dhows had African crewmembers, but Colomb did not find they were being held against their wishes; nor did they seem abductees nabbed for a quick sale at a northern market. One by one, Colomb permitted the dhows to go on their way, giving them certificates indicating they had been passed by him in case another of the squadron stopped them.

Next, Saleh bin Moosa led in a wiry middle-aged man, followed by an African boy of about ten. Through the interpreter Colomb asked the boy to wait outside. The dhow captain’s eyes darted around the room, then he handed Bin Moosa his papers, knelt, and thrust his balled hands into his cheeks to wait, still, but for those eyes. Among his papers was a form from the sultan of Zanzibar certifying the dhow as a legitimate merchant. One of the other captains in Heath’s squadron had shown Colomb an example of one in Bombay. Cross-examination followed. The dhow was supposed to have been from Sur, the great trading centre, up and round the Arabian coast to the north-west. The ship had left Zanzibar about a month earlier, sold grain at Mukalla, and was heading to Sur with the proceeds.

Then Bin Moosa and the man spoke more loudly in quick exchanges ending in apparent appeals to heaven.

‘What is the matter, Moosa?’

Turning, planting his finger on the round table. ‘This Arab man speak lie.’

Colomb dismissed the dhow captain and Bin Moosa led in the boy. He was at least not starved, even healthy. Colomb observed him closely: so little emotion from him, wooden. Philip Colomb imagined that misery and helplessness must dull the senses of captives like this boy. But the captain also shared the common prejudice that such an African acceded to his fate because he did not share the Englishman’s innate love of liberty. Love of freedom, he imagined, was inborn in British blood, not so in most other – to his mind, lesser – races.

Bin Moosa turned and pronounced the boy an obvious slave.

‘Very well, now ask him where he came from.’

There was further exchange in Swahili. ‘Come from Angoche – Zanzibar – in a dhow.’ Angoche, the stronghold of slavers in the Portuguese sphere that a seventeen-year-old George Sulivan had attacked without success.

‘Ask him if any more slaves came up with him.’

None.

‘Ask him if he can speak Arabic.’

He could not. To Colomb’s mind, this fact was key in distinguishing between an East African who signed on to a dhow for wages and a captive.

Colomb dismissed the child to a corner of the Dryad away from the dhow’s crew, and soon summoned the dhow captain again.

‘Moosa, ask him how many slaves he brought from Zanzibar.’

An exchange in Arabic, becoming loud, ending in a sort of sob out of the man’s mouth. He denied that he had any slaves on board. The boy was an orphan from Sur, had travelled to Zanzibar, and was now returning home.

Colomb had a member of the dhow’s crew brought in, including an Arab boy, not too much older than the East African child. Bin Moosa questioned him and the boy, calm and without hesitation, said that the African boy had come on at Zanzibar. Two other crewmembers cited two different Arabian towns as the boy’s original home.

Colomb had the dhow captain and child brought in together.

‘Now, Moosa, you tell him I must take his dhow.’

The small man wept. He put a question to Bin Moosa. Could the captain take the boy and let him go?

‘No, Moosa, tell him I cannot do that. Tell him I must burn the dhow. But ask him where he got that boy.’

More crying. He had bought him at Zanzibar for fourteen silver Maria Theresa dollars. He expected to sell him for thirty at Sur. Meanwhile, he transported 200 silver dollars on the ship, which would now go in a strongbox on the Dryad.

Colomb felt two chief sources of satisfaction: that he had tried the case scrupulously and so that the dhow captain was cornered into a confession; and that when this man next visited the slave market at Zanzibar he would remember the time he had lost his or his master’s ship and silver for the sake of a single small boy. On the other hand, though he sensed it was an improper thought, Philip Colomb believed that the punishment exceeded the crime; one African boy’s life was not worth 200 silver dollars (£40) and the price of a ship.1

HMS Nymphe, Zanzibar harbour, April 1869

While Dryad was springing her trap off the north-east Arabian peninsula, Edward Meara and the Nymphe hunted along the East African coast on her way to Zanzibar until she came to rest in its harbour. The crew was not at rest, but Edward Meara did not bother to send out the boats since it was unlikely a slaver would depart with Nymphe watching. Collect their victims on shore, smother them on slave decks beneath the waterline, yes; but it was something else to run out under the eyes of a known slaver-hunter – and one with a growing reputation. The crew washed and mended, made repairs, cleaned the holds, stocked fresh food, reorganised. The black sloop would soon leave to take its place in the spider’s web to the north.

Night brought little relief from the day’s heat – nearly 90 degrees even under clouds that day, perhaps 5 degrees cooler after dark, while the wind barely moved. About an hour after midnight Edward Meara received a note. A man carried a message from the island’s British consul and pleaded that the captain might read it immediately.

So Meara read how the British consulate had received information from a source who must remain secret but who was perfectly trustworthy: slavers from the north were loading a dhow with slaves under cover of darkness not far away. Not far, in fact, from the British consulate itself which fronted on the shore. Meara could be perfectly assured that these were illegal slavers – not those permitted to move slaves within the sultan’s dominion by the terms of his treaty with Britain. Would Commander Meara investigate?

A rush of activity followed as Meara ordered Lieutenant Norman Clarke to lead the two cutters on a raid. Clarke had boarded countless dhows around Madagascar and along the African coast – had even gone ashore and tried to track slavers’ captives inland, a dangerous thing. He was something like Meara, a son of gentry in the back of the line to be lord of his father’s manor. Today was Clarke’s twenty-fourth birthday and this mission could make his name.

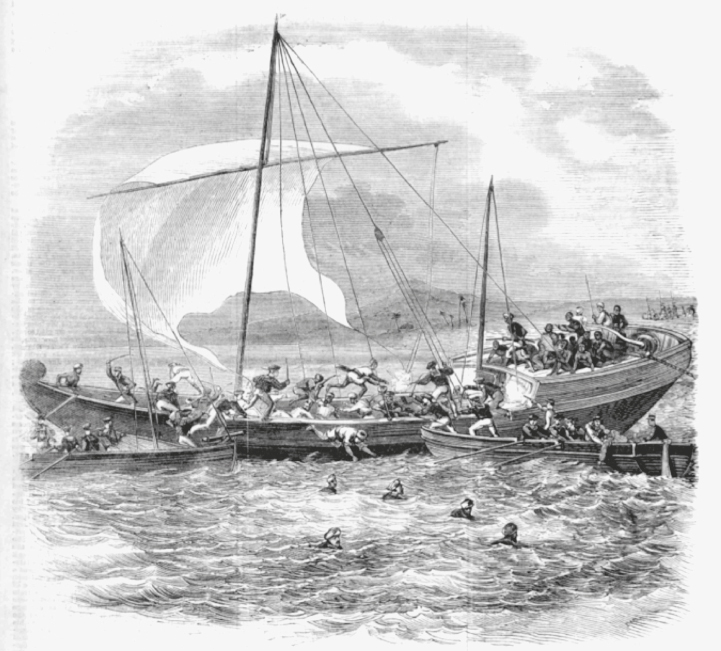

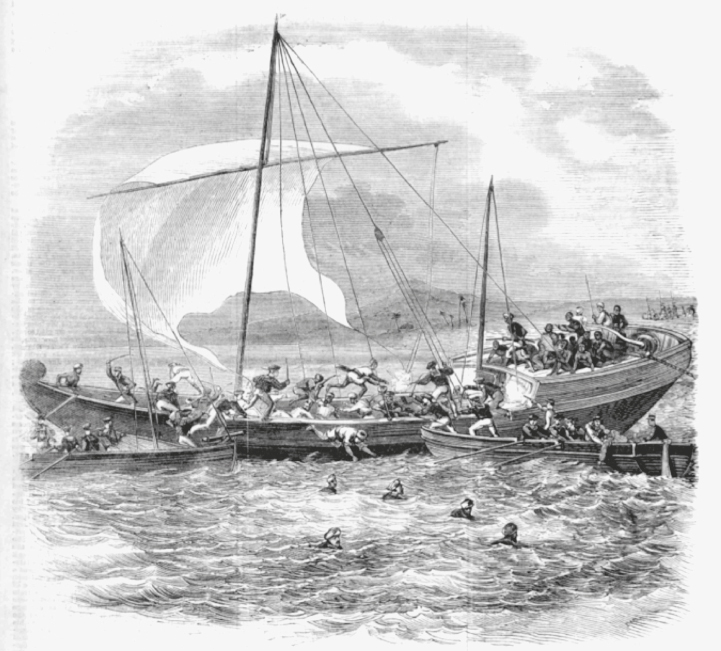

The crew of the Nymphe swung the cutters out over the water and lowered them, manned and armed the boats, and raised their masts and ran up their sails. Clarke and his men crossed the harbour in the dark and found the large dhow where it was promised to be loading. It was only about twenty yards from shore, held off it by a stern line, while there was busy movement on shore close by. Clarke gave the order to board and the boats’ crews climbed the ship’s sides. Immediately the dhow’s crew began jumping from the ship, splashing and swimming toward the beach.

The crew of the Nymphe boarding a dhow in Zanzibar

There were Africans on deck, more apparently below: a full slaver. A crewmember – the captain? – began cutting the stern line, apparently hoping the ship would drift on the breeze to shore where the men on the beach might then be able to retake the dhow from the boarders.

Now came a shot from the shore. Now perhaps thirty muskets firing on the raiding party. Clarke returned fire with his revolver and his men with their rifles. But beyond the muzzle flashes, their targets on the beach were hard to see: they could only fire into darkness at the flashes. Still, Clarke expended his revolver. Then he drew his dirk and rushed a man in the stern who was hacking at the cable tethering the ship. The man turned, holding a spear. Clarke cut, striking the man’s arm, but he fought on, thrusting his spear low. The point entered Clarke’s thigh and came bloodily out of the other side. By now the man was long since the last defender of the dhow. With Clarke wounded, he leapt overboard to join his men on shore, but he was shot by one of the Nymphe’s crew and never reached it.

Firing continued, and it seemed the slavers on the shore had a far better view of the dhow and the sailors against the sea and horizon. Musket balls zipped past Clarke and his boarders. A bullet passed through Clark’s cap like an unrealistic scene in a penny dreadful. Then more blood, as a bullet burst out of the hand of Sub-Lieutenant Tom Hodgson. It had entered his elbow, burrowed down his arm, irrupted from his hand and flown on. Then able seaman William Mitchell was hit in the thigh: a dangerous wound – blood was leaving him quickly.

Norman Clarke ordered that the dhow be tethered to one of the cutters as musket balls continued to rip through the air. He ordered Sub-Lieutenant Hodgson on board the other cutter, while some boatmates helped the heavily bleeding William Mitchell onto it. It cast off and hurried for Nymphe.

Though outnumbered, the Nymphe crewmen on board the dhow and the remaining cutter did their best to cover for the retreating boat with their rifles. Pull back the hammer half way – flip open breech block – pull the extractor back a bit to free the empty case – flip the rifle to drop the case – slide in a heavy cartridge – flip breech block closed – pull the block back to fully cocked – aim and pull the trigger. An echoing pop and a little cloud of dark smoke. Repeat. Ten shots a minute, a terrifically quicker rate of fire than that of the muskets. Fifteen minutes of fighting passed. Beside the man dead in the water, it was unclear how many slavers were shot. Another fifteen minutes. The men on shore began to break rank until, before another quarter hour passed, the firing from the shore stopped. Then Clarke and the remaining boat’s crew hauled off the dhow and headed out for Nymphe.

On the ship, Meara had heard the storm of firing within half an hour of his boats’ departure across the harbour. First he saw one cutter return with Tom Hodgson bleeding, William Mitchell bleeding far worse. Then, finally, life finished pouring out of William Mitchell, whose twenty-fifth year proved his last.

Then forty-five minutes later the second cutter returned, towing a dhow covered with freed captives, 136 men, women and children. The British consul came up the side of the Nymphe soon after that, still well before dawn. He spoke Swahili and began asking the East Africans where they had come from and who their captors had been.

Then came dawn, came distant thunder, but little wind, and what rain fell did not cool the air. It was Sunday, but no awning was spread for Bible text and prayers. Throughout the afternoon, the hands cleaned the slave ship lashed alongside. Then shortly after four in the afternoon, twelve hours after he had died, young William Mitchell was lowered into one of the boats. Meara descended with other officers and sailors.

The boats pulled for a little coral island just outside the harbour to the north-west, a narrow islet, uninhabited; a green, pleasant place that the sultan had reserved for Christian burials. The boats touched shore, the first dry land Mitchell had occupied in some time. They took him to his place, they lowered him down, said the words over him. As darkness came on, Edward Meara and the others left the island. And William Mitchell was alone when night came.2