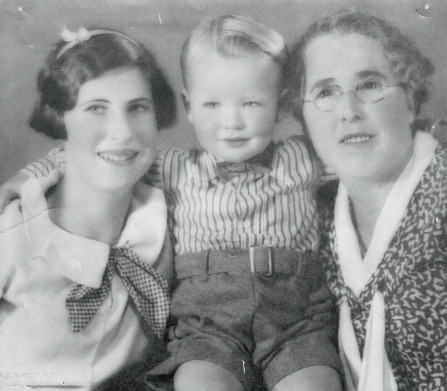

IN APRIL 1934, SIX YEARS AFTER Jimmy’s death, George and Alice again made the journey to Newcastle in the old green kerosene-powered truck, this time with ten-year-old Charlotte squeezed between them. At Newcastle Hospital they signed the final papers and collected a healthy three-month-old boy with wisps of white-blond hair. Who knows why his mother had been forced to abandon him. Well, I’m sure that Alice suspected why, and that she was relieved she hadn’t ended up pregnant with John Henry Edwards’ child. I wonder if the relief of not having to face an unwanted pregnancy, and a likely forced adoption, had softened the pain of his lies and her humiliation. Pregnancy by a bigamist would not have been a good look in Partick parish in 1918—and especially not for the choirmistress.

But now, Alice and George officially had a new son: John. Did it bother Alice that her son shared the name of the bigamist? Perhaps, being such a common name, it was easier to bear as sheer coincidence. According to my aunt Charlotte, John was the name that his biological mother had chosen for him, and that was good enough for Alice. Staring at her new baby, I can only imagine how Alice’s heart burst with love for him as she yearned for James, the son she had lost. I wonder if she thought much over the years about the woman who gave my father up for adoption—and about whether the agony of giving up a baby and wondering, year in, year out, where he was, how he was, who he was, and dying without ever seeing him again, would be even more difficult than burying one’s own child.

Under any circumstances, the decision to adopt a child is enormous. But for Alice and George Lloyd, having raised a daughter for ten years and having endured the loss of a son, to take on the care of a newborn baby was an act of almost unfathomable hope. Their generosity in adopting John does not quite gel in my mind with the apparent lack of maternal feeling Alice displayed toward Charlotte, or her severity to other members of her family. Such as her daughter-in-law, my mother.

‘Your father was Mummy’s little soldier,’ Aunt Charlotte told me. ‘She always preferred boys.’

John, who grew up knowing he was adopted, never felt compelled to find his birth mother. Over the years, whenever I asked him about it, he said, ‘I had a happy childhood, and I knew I was loved.’ John survived the inherent life-limiting risks of a bush upbringing, endured every minute of school until he could leave at fifteen, and worked in his father’s stock and station agency. Too young to go to war, John moved to Sydney to live with Charlotte, who had married and moved there five years earlier. In 1955, when he met my mother Pamela at Vic’s Cabaret at Strathfield, in Sydney’s inner west, John was twenty-one, and a busy subcontractor to builders and property developers.

‘He was the nicest man I’d ever met,’ my mother told me.