The heavens darkened and Nat Turner prepared to strike. Rising from the gloom of Virginia’s swamps, he resolved to slay his enemies. The February eclipse, a black spot on the sun, signaled that the time to act had arrived.

“I had a vision—and I saw white spirits and black spirits engaged in battle, and the sun was darkened—the thunder rolled in the Heavens, and blood flowed in streams.”

The visions continued—blood drops on corn, pores oozing blood, markings on bloodstained leaves. He felt the Holy Spirit within, felt awakened and ordained for some special purpose. Following the eclipse, Turner told four other slaves of the work to be done, the “work of death” to begin on the Fourth of July.

The time for violent insurrection had arrived, but no one could decide how best to proceed. The conspirators squabbled over plans and Turner became ill. The Fourth passed without a strike for freedom. And then, on Saturday, August 13, “the sign appeared again.” Across the East Coast, noted an observer in Philadelphia, the “western heavens seemed as one vast sea of crimson flame, lit up by some invisible

agent. Thousands of our citizens gazed at the spectacle—some with wonder, others with admiration, and others fearful that it was a sad augury of coming evil.” 1

Newspaper editors tried at first to contain the fear that leaped like a brushfire from door to door. Word was spreading of a general insurrection in Southampton County, Virginia, where the enslaved outnumbered the enslavers by over a thousand. Across Virginia there were nearly five hundred thousand slaves, and the total throughout the South reached two million souls. It could not be, they told themselves. The slaves were content. Slavery was a righteous institution. They were good masters. Indeed, some of them were. Even Joseph Travis, Nat Turner attested, “was to me a kind master.” But kindness did not save him at 2 A.M. on August 22 from the force of a blunt hatchet against his head, followed by the deathblow from an ax. Nor did it save Mrs. Travis. Nor four others, including an infant who was initially overlooked and then also killed. There were no innocents. In the stillness of a sultry night, the murders that fueled the rumors had begun.2

“On the road, we met a thousand different reports, no two agreeing, and leaving it impossible to make a plausible guess at truth.” How many slaves were involved? Some accounts said only three, some said four hundred, and some claimed over a thousand rebels, banditti, brigands, villains, wretches, monsters—called every name but men. At first, the papers reported that the insurrection was led by about 250 runaways who emerged from the Great Dismal Swamp for the purpose of “plunder and rapine,” “to rob and to do mischief.” They had come from a “Camp Meeting,” a religious revival, and were deceived by “artful knaves” into launching an attack. The plan, some said, extended deep into North Carolina, and was “started by a white man, for some design unknown.” But then rumor had it that the rebels were slaves, “the property of kind and indulgent masters.” It started not with hundreds, but with six, and “there appears to have been no concert with the blacks of any other part of the state.” The plan came from a slave, Nat Turner, a literate preacher who acted “without any cause or provocation.”3

Neither rumor offered much solace. “Runaways” meant the attack came from without; “slaves” meant it came from within. Although the one rumor frightened people by portraying the uprising as more widespread than it was, it also allowed citizens to explain the tragedy in terms of a need for food and clothing and as the work of outside agitators. The other rumor limited the scope of the event, but allowed it to be accounted for only in terms of retribution, a blow for freedom originating from inside the slave community. Had it been runaways, the residents of Southampton County might have gone on as before. But it turned out to be slaves, and Virginians knew they could “never again feel safe, never again be happy.”

First reports minimized the bloodshed, stating only that several families had “fallen victim.” Though editors cautioned readers not to believe “a fiftieth part” of what they read or heard, a letter written on August 24 and published two days later claimed that between “eighty and one hundred of the whites have already been butchered—their heads severed from their bodies.” An editor for the Constitutional Whig in Richmond, John Hampden Pleasants, belonged to a mounted militia unit sent to suppress the rebellion. From Jerusalem, the main town in Southampton County, he forwarded the first accounts of the tragedy. Although rumors exaggerated the number of insurgents, “it was hardly in the power of rumor itself, to exaggerate the atrocities: … whole families, father, mother, daughters, sons, sucking babes, and school children, butchered, thrown into heaps, and left to be devoured by hogs and dogs, or to putrify on the spot.” Among those murdered were Mrs. Levi Waller and the ten children in her school, the bodies “piled in one bleeding heap on the floor.” A single child escaped by hiding in the fireplace. Pleasants misidentified Turner as “Preacher-Captain Moore” and placed the death toll at sixty-two. By August 29, when his letter appeared, the two-day insurrection was over, Turner was in hiding, and those captured rebels who survived faced trial and execution.4

For the next three months, newspapers in Virginia and throughout the nation tried to explain the tragedy. Many accounts kept returning

to the innocence of children and the vulnerability of women. Near the end of the rampage, Turner’s band approached Rebecca Vaughan’s residence. It was noon. Mrs. Vaughan was laboring outside, preparing dinner, when she saw a puff of dust rising from the road. Suddenly, some forty mounted and armed black men came rushing toward the house. She raced inside, quivered at the window, and, through the snorting of horses and shouting of men, begged for her life. The shots that killed her brought her fifteen-year-old son, Arthur, from the fields. As he climbed a fence, he too was gunned down. A niece, Eliza Vaughan, “celebrated for her beauty,” ran downstairs and out the door but made it only a few steps away. One editor could not conceive of a situation more “horribly awful” than that faced by these women: “alone, unprotected, and unconscious of danger, to find themselves without a moment’s notice for escape or defence, in the power of a band of ruffians, from whom instant death was the least they could expect.”

Lurking beneath these accounts was a dread that the rebels had raped the women, that the slaveholders had failed to protect not only the lives of their wives and daughters but their purity as well. Across the centuries, accusations of rape were never far from the surface when white men thought about black men with white women. Virginians worried feverishly about it here. Many rumors took wing in the late days of the summer, but writers sought quickly to assure readers, “It is not believed that any outrages were offered to the females.”

Driven by hatred and fear, the forces that extinguished the rebellion displayed a ruthlessness that startled some observers. No one in the South, of course, defended the rebels, but the actions of the soldiers in putting down the rebellion generated controversy. Enacting scenes “hardly inferior in barbarity to the atrocities of the insurgents,” the militia beheaded some of the rebels in the field. One of the mounted volunteers from Norfolk had in his possession “the head of the celebrated Nelson, called by the blacks, ‘Gen. Nelson,’ and the paymaster, Henry, whose head is expected momentarily.” Soldiers stuck the severed heads of several dozen slaves on poles and planted them along the highway, a warning to all who passed by. Those who

survived capture would be tried, and on September 4 the state started executing the convicted, but the summary justice in the field raised concerns. Pleasants was the first to express dismay over the decapitation of the rebels. “Precaution is even necessary to protect the lives of the captives,” he concluded. He worried that revenge would “be productive of further outrage, and prove discreditable to the country.” A week later, the paper altered its stance, stating that “the sanguinary temper of the population who evinced a strong disposition to inflict immediate death on every prisoner” was understandable and extenuated by their having witnessed unspeakable horrors to their wives and children. Readers, however, did not forget Pleasants’s initial comments; perhaps here, in his call for restraint, he took the first step that would lead to his death when, fifteen years later, the editor of the Richmond Enquirer accused him of abolitionist tendencies and shot him in a duel.

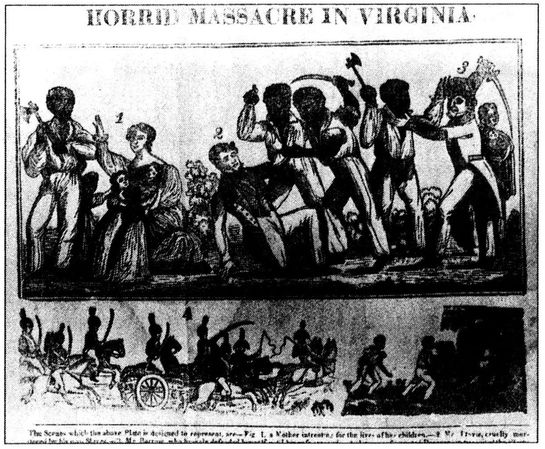

4. “Horrid Massacre in Virginia,” fold-out frontispiece from Samuel Warner, Authentic and Impartial Narrative of the Tragical Scene (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society)

Some who warned against further revenge did so out of a desire to protect the owners of those slaves who did not participate in the insurrection and to re-establish the rule of law. “A public execution in the presence of thousands,” advised the military commander, “will demonstrate the power of the law, and preserve the right of property. The opposite course, while it is inhuman and therefore not to be justified, tends to the sacrifice of the innocent … . This course of proceeding dignifies the rebel and the assassin with the sanctity of martyrdom.”

Between private revenge and public justice resided conflicting messages. Barbaric revenge told the enslaved that, should they ever try to revolt again, genocide would be the result: “Another insurrection will be followed by putting the whole race to the sword.” And yet such a threat carried with it a tacit acknowledgment that the enslaved were not loyal and contented, that slavery was not benign, and that the outnumbered white population could rule only through terror and fear. The enactment of legal, public justice demonstrated that whites could maintain civil society and that they viewed rebellion, however horrific, as an aberration. Yet it also suggested a concern with the property rights of slaveholders and a desire not to provoke the enslaved by creating martyrs to the cause of freedom. Either way, in the immediate aftermath of the rebellion, editors worried about accounts and actions that would “give the slaves false conceptions of their numbers and capacity, by exhibiting the terror and confusion of the whites, and to induce them to think that practicable, which they see is so much feared by their superiors.”5

Stories of loyal slaves provided some solace. On the morning of August 23, before dawn, Turner and the rebels attacked the house of Dr. Simon Blunt, who by this time had heard of the insurrection. Crippled by gout, he chose to defend his ground. Alongside stood his fifteen-year-old son, an overseer, and three other white men. They had six guns and plenty of powder. Entering the yard, one rebel fired his weapon to test whether anyone was home. Twenty paces from the

house, shots rang back, and the rebels scattered, one killed and one injured. Blunt’s slaves, some attested, “nobly and gallantly” stood by their aged master and pursued the rebels with “shouts and execrations.” One writer paid “tribute to our slaves … which they richly deserve … . There was not an instance of disaffection, in any section of our country; save on the plantations which Capt. Nat visited, and to their credit, the recruits were few.” The remark said to have been uttered by the loyal slaves no doubt made the slave owners grin: “If they had to choose a master; it would never be a black one.”6

In presenting Turner not as a liberator but as a false messiah, writers offered an answer to the question being asked across the country: “Who is this Nat Turner? Where is he from?” Accounts portrayed him as unremarkable-looking. A letter to the governor described Turner as “between 30 & 35 years old—5 feet six or eight inches high—weighs between 150 & 160 rather bright complexion but not a mulatto—broad-shouldered—large flat nose—large eyes—broad flat feet rather knock kneed—walk brisk and active—hair on the top of the head very thin—no beard except on the upper lip and tip of the chin.” However average he might be in appearance, his religious fanaticism distinguished him. In 1828, he had dipped into cool, dark water with a white man and emerged a baptized, self-anointed preacher. Writers called him “cunning” and “fanatical,” a scoundrel who claimed to be a divinely inspired Baptist preacher. Turner’s “preaching excursions” in Jerusalem and Petersburg allowed him, under the “cloak of religion,” to concoct his insurrection scheme. He played off the “superstitious hopes and fear of others,” using the eclipse to win adherents. “We are inclined to think,” claimed one commentator, “that the solar phenomenon exercised considerable influence in promoting the insurrection.”

His literacy also served as a means of persuasion, a way to “deceive, delude, and overawe” the minds of the enslaved. That Turner could preach and “read and write with ease” should serve as a warning: “no black man ought to be permitted to turn a Preacher through the country.” The writer did not specify why, but he did not have to.

The religion of the slaveholders tried to contain the impact of biblical stories of salvation and liberation, but itinerant preachers along the frontier spread the word that man was a free moral agent and that redemption was available to those who sought it. Some writers said Turner was drunk and some said he sought only to plunder. But one Southerner understood that Turner acted on an “impulse of revenge against the whites, as the enslavers of himself and his race.”7

The insurrection was over, and by the start of September the first of many executions had begun, but Turner remained at large and all were “at a loss to know where he has dropped to.” Some said he had fled to another state; others declared that he remained hidden in the area. Most thought Turner vanished in the Great Dismal Swamp, an enormous bog, thirty by ten miles long, between Virginia and North Carolina, a place “beyond the power of human conception” where “runaway Slaves of the South have been known to secrete themselves for weeks, months and years, subsisting on frogs, terrapins, and even snakes.” Time and again newspapers erroneously reported his capture. The Norfolk Herald told of a well-armed Turner being taken in a reed swamp. A writer to the Richmond Enquirer claimed that he spotted Turner some 180 miles away, on the road from Fincastle to Sweet Spring, headed for Ohio. One rumor had it that Turner drowned trying to cross New River. On another occasion, the body of a dead man thought to be Turner did not, on closer inspection, fit the description.8

It turned out that Turner had never left the vicinity of the insurrection, and on Sunday, October 30, around noon, he was captured. Turner had been hiding in the ground, in what some called a “cave” or a “den.” He had covered himself with branches and pine brush from a fallen tree. Benjamin Phipps, a local farmer, was walking past when he saw the earth move and a figure emerge. He pointed his gun at the spot.

“Who are you?” he shouted.

“I am Nat Turner; don’t shoot and I will give up.”

The accounts all made Turner out to be a coward who surrendered and threw his sword to the ground. Phipps and others transported Turner to Jerusalem. As word spread, the citizens of Southampton

County gathered. The Norfolk Herald said that given the feelings of the people “on beholding the blood-stained monster … it was with difficulty that he could be conveyed alive.” The Petersburg Intelligencer, by contrast, claimed “not the least personal violence was offered to Nat.” All the reports sought to diminish the rebel’s stature. Writers labeled him a “poor wretch,” “dejected, emaciated, and ragged,” a “wild fanatic or gross imposter” whose only honorable act was admitting the charges against him.9

On November 5, the state of Virginia tried, convicted, and sentenced Nat Turner. In the days prior to his trial, Thomas R. Gray, a lawyer and slave owner who had served as court-appointed counsel for several slaves tried in September, interviewed the prisoner in his cell. Gray spoke with Turner on November 1, 2, and 3; he also attended the examination of Turner by two justices on October 31. In an unsigned letter sent to the Richmond Enquirer, Gray called Turner a “gloomy fanatic” who gave “a history of the operations of his mind for many years past.” Gray expressed dismay that “I could not get him to explain in a manner at all satisfactory” how the rebel conceived the idea of emancipating the slaves. The letter-writer teased that he intended to provide a “detailed statement of his confessions, but I understand a gentleman is engaged in taking them down verbatim from his lips.”

Gray was himself that gentleman, and whatever other interests he had in Turner’s story—civic duty, public curiosity, historical documentation—financial concerns topped the list. His holdings in land and slaves had been slashed over the preceding two years, and Gray seized the opportunity to produce a pamphlet guaranteed to sell. He obtained a copyright on November 10, and two weeks later he published The Confessions of Nat Turner. Gray had accurately gauged interest in Turner; the pamphlet sold tens of thousands of copies. It provided the fullest account of what had taken place and offered Turner’s story through the prism of his interviewer’s point of view.10

As a literary genre, last words and dying confessions dated back to the seventeenth century in America and served as part of the ritualistic requirements of execution day. In these texts, the condemned provided

the details of the crime, pleaded for forgiveness, offered a warning to others, and displayed signs of true repentance. The actual beliefs and feelings of the criminal played little part in the production, which sought only to serve as a sign of the restoration of civil and religious order. The Confessions of Nat Turner stands apart from the dozens of other works in this genre. The interviewer is a presence in the text; both Gray and Turner have stories to tell; the prisoner does not warn others against following in his steps, nor does he seek forgiveness. Indeed, he pled not guilty, “saying to his counsel that he did not feel so.”

The Confessions begins and closes with Gray’s effort to establish authenticity. The opening page includes the clerk’s seal of the full title as submitted for copyright: “The Confessions of Nat Turner, the leader of the late insurrection in Southampton, Virginia, as fully and voluntarily made to Thomas R. Gray, in the prison where he was confined, and acknowledged by him to be such when read before the Court of Southampton.” The closing page includes a court document claiming that the justices used the confessions at trial to convict Turner and that when asked if he had anything to say Turner responded, “I have made a full confession to Mr. Gray, and I have nothing more to say.” The trial record suggests otherwise. Neither Gray nor any confessions were mentioned, and Turner said only that he had nothing more to say than what “he had before said,” more likely a reference to his interview with the justices than with Gray. But Gray wanted to identify himself as a central figure in the proceedings and to persuade the public not only to trust the stories told in the Confessions, but also to buy the pamphlet.

Gray offered Southerners what they needed to hear and wanted to believe. He opened the work with a signed address to the public, stating that the Confessions would at last provide an antidote to a “thousand idle, exaggerated and mischievous reports.” Here at last, in the words of Turner himself, the motives of the rebels would be revealed. The insurrection, Gray declared, was “entirely local,” the “offspring of gloomy fanaticism.” Its origins lurked in Nat Turner’s history, in “the operations of a mind like his, endeavoring to grapple with things beyond its reach.” Turner’s revolt, Gray suggested, was a terrible aberration,

“the first instance in our history of an open rebellion of the slaves,” and it should not alter the public’s view of the enslaved as submissive and docile. When confronted, the rebels “resisted so feebly, when met by the whites in arms,” and Turner himself, the “great Bandit,” was captured by “a single individual … without attempting to make the slightest resistance.” The lesson for the community was to “strictly and rigidly” enforce the laws that governed the enslaved. Gray did not have to specify that he meant especially those laws against teaching slaves how to read and permitting them to preach.

A perceptive reader might have found the brief opening more unsettling than comforting, for Gray hit upon an unresolvable tension at the core of American culture: whatever appearance might suggest, reality would prove otherwise. “It will thus appear,” Gray lamented, “that whilst every thing upon the surface of society wore a calm and peaceful aspect; whilst not one note of preparation was heard to warn the devoted inhabitants of woe and death, a gloomy fanatic was resolving in the recesses of his own dark, bewildered, and overwrought mind, schemes of indiscriminate massacre to the whites.” Who was to say that some other Nat Turner was not at this moment planning to strike? What made it worse was that Turner’s actions were “not instigated by motives of revenge or sudden anger, but the results of long deliberation, and a settled purpose of mind.” Unlike any other event, Turner’s revolt punctured the fragile worldview of the slaveholding class. As long as slavery remained, Southerners would wonder and worry about the behavior of their chattels, and they would always have to watch their backs.

Turner also spoke of appearances—the appearance necessary to sustain the belief that he was destined for some special purpose: “Having soon discovered to be great, I must appear so, and therefore studiously avoided mixing in society, and wrapped myself in mystery, devoting my time to fasting and prayer.” Turner’s story is a narrative of religious awakening. To explain the insurrection, “I must go back to the days of my infancy, and even before I was born.” As a child, Turner identified events that happened before 1800, the year of his birth. The

slave community proclaimed that he would be a prophet; his parents interpreted marks on his body as indicating that he was meant “for some great purpose.” Turner, deeply attached to his grandmother, “who was very religious,” felt emboldened by his spiritual and intellectual gifts. He had a “restless, inquisitive and observant” mind and was self taught in reading and writing. (Even Gray spoke of Turner’s “natural intelligence and quickness of apprehension.”) Turner heard the Spirit speak to him, and he believed that he was ordained for some special purpose. Twice Turner stated that he overheard others remark that “I had too much sense to be raised, and if I was, I would never be of any use to any one as a slave.”

But in his first attempt at prophecy, he seemed to defend rather than attack slavery. In his early twenties, Turner ran away from an overseer and remained in the woods for thirty days, but he returned upon hearing the Spirit command him to follow “the service of my earthly master.” The message of obedience that he brought back did not sit well with the other slaves. “The negroes found fault, and murmured against me, saying that if they had my sense they would not serve any master in the world.” The story should have deepened the despair of Gray and his readers. Turner’s decision to rebel against slavery came less from God than from fellow slaves. Immediately after being spurned, Turner had his first vision of darkened sun, rolling heavens, and red-flowing streams.

In every way, Turner’s narrative resisted the interpretation Gray strove to provide. When Turner had told his interviewer of a revelation in 1828 that “the time was fast approaching when the first should be last and the last should be first,” Gray asked, “Do you not find yourself mistaken now?” Turner responded with his own question: “Was not Christ crucified?” Asked whether the conspiracy spread beyond Southampton County, Turner inquired, “Can you not think the same ideas, and strange appearances about this time in the heavens might prompt others, as well as myself, to this undertaking.” Neither the kindness of the individual master nor the impracticability of the scheme mattered. Turner chose to “carry terror and devastation” wherever

he went, and he narrated the massacre of entire families with a dispassionate, almost scientific tone. Gray ended the Confessions by recounting the stories of individuals who by luck and grace survived, but Turner’s “calm, deliberate composure” unsettled the interviewer: “I looked on him and my blood curdled in my veins.”11

By the time the Confessions appeared, Turner had been hanged and dissected. Some said he sold his body for ginger cakes, but his body was not his to sell. Folk legends had it that he was skinned, his flesh fried into grease, and his bones ground into souvenirs. Whatever happened to his body, his voice remained, captured in the text published by Gray. One reader, at least, declined to believe that Turner spoke the words attributed to him. “The language,” he claimed, “is far superior to what Nat Turner could have employed—Portions of it are even eloquently and classically expressed.” The reader refused to accept the authenticity of Turner’s words because to do so would violate his assumptions about the intellectual capacities of slaves. But such reservations helped make the case that the words transcribed from speech to print were indeed uttered by Nat Turner. Gray did not put the Confessions into a dialect meant to imitate the supposed everyday speech of slaves; the very literacy that would seem to belie the authenticity of the text helps confirm it. Furthermore, Gray repeatedly praised Turner for his qualities of mind. Preacher and prophet, Turner early in life discovered the power of language, and he used it to win adherents: “On the sign appearing in the heavens, the seal was removed from my lips, and I communicated the great work laid out for me to do.”12

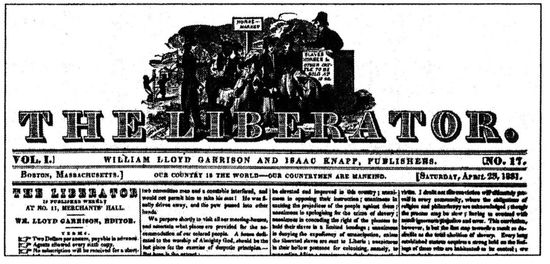

THE LIBERATOR

The work of liberation and retribution begun by Turner in Virginia opened a national debate that fueled sectional rivalries between North and South and triggered a wide-ranging discussion over what to do about slavery in Virginia. In assessing the multiple causes of the rebellion, Southern writers placed Northern interference high on their list.

Even in praising Northerners for their sympathy, Southern editors displayed acute sensitivity to sectional tensions. One writer expressed relief that in most Northern newspapers “we have seen no taunts, no cant, no complacent dwelling upon the superior advantages of the non—slave holding states … . We have no doubt, that should it ever be necessary, the citizens of the Northern states would promptly fly to the assistance of their Southern brethren.” The Alexandria Gazette quoted New York papers that expressed support and offered “arms, money, men … for the defense of our Southern brethren.” “The spirit of the times,” opined the New York Telegraph, “rebukes discord, disorder, and disunion.”13

The problem, thought most Southerners and Northerners, was a small but influential group of reformist demagogues and religious fanatics who nurtured disaffection and fomented servile insurrection. “Ranting cant about equality,” a Southerner argued, heated the imagination of the enslaved and could create the only force that might lead to a general insurrection across the South—“the march of intellect.” One writer cautioned “all missionaries, who are bettering the condition of the world, and all philanthropists, who have our interest so much at stake, not to plague themselves about our slaves but leave them exclusively to our management.” Particularly obnoxious—and dangerous, from the Southern perspective—was the circulation of Northern abolitionist newspapers which “have tended, in some degree, to promote that rebellious spirit which of late has manifested itself in different parts” of the South. Refusing to believe slaves capable of plotting an insurrection on their own, and disavowing any precedents or provocations for rebellion among the enslaved, Southerners blamed the timing and ferocity of Turner’s revolt not on the darkening of the heavens but on the actions of outside agitators. And of all the missionaries, philanthropists, politicians, and abolitionists who challenged slavery, one alone seemed culpable for the events at Southampton: William Lloyd Garrison and his newspaper The Liberator.14

In an address to the public on January 1, in the first issue of The Liberator, Garrison explained his position on slavery. Invoking the principles

of the Declaration of Independence, Garrison demanded the immediate, unconditional abolition of slavery and vowed to use extreme measures to effect a “revolution in public sentiment.” He proclaimed he would abjure politics and refuse to ally himself with any denomination. Instead, he desired a brotherhood of reformers willing to raise their voices to defend “the great cause of human rights.” He warned that he would not compromise, nor would he rein in his words: “I will be as harsh as truth, and as uncompromising as justice. On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write with moderation. No! No! Tell a man whose house is on fire, to give a moderate alarm; tell him to moderately rescue his wife from the hands of a ravisher; tell the mother to gradually extricate her babe from the fire into which it has fallen;—but urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.”

Garrison, who grew up in Newburyport, Massachusetts, began his working life as a writer and editor for assorted newspapers in New England. In 1829, at age twenty-four, he joined Benjamin Lundy in Baltimore as co-editor of the Genius of Universal Emancipation, an antislavery newspaper started by Lundy in 1821. The two men differed temperamentally. Lundy, a Quaker, had none of his associate’s zeal. He favored gradual, moderate approaches toward the abolition of slavery and wrote in careful, measured phrases. But he knew that his paper needed revitalizing, and he chose the right person for the job. Though Garrison was not yet the radical abolitionist he would soon become, in 1829 he was already pushing the boundaries of the antislavery argument. In a Fourth of July address at the Park Street Church in Boston, he proclaimed that slaves possessed inherent and unalienable rights, that the churches did nothing for the enslaved, that the nonslaveholding states were complicit in the guilt of slaveholding, and that with freedom and education blacks would be equal to whites in every way. The time to act, he declared, was now: “If we cannot conquer the monster in his infancy, while his cartilages are tender and his limbs powerless, how shall we escape his wrath when he goes forth a gigantic

cannibal, seeking whom he may devour. If we cannot safely unloose two millions of slaves now, how shall we unbind upwards of TWENTY MILLIONS at the close of the present century?”15

It did not take Garrison long to find an object for scorn and derision, a target for the words that fired forth with such intensity. When he discovered that a fellow townsman from Newburyport, Francis Todd, owned the brig Francis, which transported seventy slaves from Baltimore to New Orleans, it was too much for him to take. “I am resolved to cover in thick infamy all who are concerned in this nefarious business,” he proclaimed. In a November 1829 issue of the Genius, he excoriated Todd and the boat’s captain for their participation in the domestic slave trade. Exposing the source of their wealth, he labeled them “enemies of their own species—highway robbers and murderers.” “Unless they speedily repent,” Garrison warned, they would one day “occupy the lowest depths of perdition.” For his vituperative comments, Garrison faced criminal and civil charges of libel. Following a brief trial, the editor was found guilty and fined fifty dollars and costs. He refused to pay, and authorities imprisoned him in the Baltimore jail for seven weeks in 1830 until a wealthy New York abolitionist, Lewis Tappan, paid the fine.16

Those weeks in jail transformed Garrison. From his cell, he wrote Todd: “I am in prison for denouncing slavery in a free country! You, who have assisted in oppressing your fellow-creatures, are permitted to go at large, and to enjoy the fruits of your crime.” Garrison’s rage deepened as he contemplated the injustice of his treatment. An editorial in his former paper, the Newburyport Herald, called him vain and vehement. Garrison responded: “If I am prompted by ‘vanity’ in pleading for the poor, degraded, miserable Africans, it is at least a harmless, and, I hope, will prove a useful vanity … a vanity calculated to draw down the curses of the guilty … a vanity that promises to its possessor nothing but neglect, poverty, sorrow, reproach, persecution, and imprisonment.” As for vehemence, “the times and the cause” demanded it, because “truth can never be sacrificed, and justice is eternal. Because great crimes and destructive evils ought not to be palliated, or great

sinners applauded.” From his cell, Garrison witnessed firsthand the effects of slavery as he heard slave auctions conducted and observed as masters came to reclaim their fugitive slaves. He made eye contact with the enslaved and came to compare his own situation, his own “captivity,” to their fate.17

In prison, Garrison experienced a final awakening. His confinement led him to identify so strongly with the sufferings of the enslaved that he felt he would burst if forced to endure one more day. To be sure, one can find in pre-Baltimore Garrison the views of post-Baltimore Garrison. But his prison experience liberated him: “The court may shackle the body, but it cannot pinion the mind.” Garrison imagined what it meant to die unfree, to be made “an abject slave, simply because God has given a skin not colored like his master’s; and Death, the great liberator, alone can break his fetters!”

Garrison fled Baltimore and found his way back to Boston, where in the fall he announced plans to start a newspaper that would insist upon the immediate abolition of slavery. He called it The Liberator and proclaimed that the slaves must be freed not in death but in life. Garrison sought public absolution from what he now saw as his earlier sinful belief that “the emancipation of all the slaves of this generation is most assuredly out of the question.” On January 1, 1831, Garrison offered “a full and unequivocal recantation” of the gradualist position that left millions to die in slavery. He begged “pardon of my God, of my country, and of my brethren the poor slaves, for having uttered a sentiment so full of timidity, injustice, and absurdity.”18

No one would ever again accuse Garrison of timidity. He not only agitated for the immediate abolition of slavery in the South, he also struggled for the equal rights of free blacks in the North. In June, he attended a convention of free people of color in Philadelphia. “I never rise to address a colored audience,” he confessed, “without being ashamed of my own color.” With Independence Day celebrations a few weeks away, Garrison admitted, “If any colored man can feel happy on the Fourth of July, it is more than I can do … . I cannot be happy when I look at the burdens under which the free people of color labor.” “You

are not free,” he lamented, “you are not sufficiently protected in your persons and rights.” Garrison saw hope in the Constitution of the United States, which “knows nothing of white or black men; it makes no invidious distinctions with regard to color or condition of free inhabitants; it is broad enough to cover your persons; it has power enough to vindicate your rights. Thanks be to God that we have such a Constitution.” But just as Garrison came to see through gradual schemes of emancipation, so too did he lose faith in the Constitution when he recognized that, through such provisions as the three-fifths and fugitive-slave clauses, it defended slavery. Setting the document on fire, the flames lapping at his fingertips, he condemned the Constitution as a proslavery compact, “a covenant with death, an agreement with hell.”

Garrison urged free blacks to embrace temperance, industry, and piety as the means to rise. He recommended trades and education, seeing “no reason why your sons should fail to make as ingenious and industrious mechanics, as any white apprentices,” and calling “knowledge of the alphabet … the greatest gift which a parent can bestow upon his child.” He had special hopes for the creation of a black college in New Haven that would combine manual arts with higher education. “What Yale College … has done for the whites,” he wished, “may in time be done by the new college for the colored people.” The delegates in Philadelphia agreed to raise ten thousand dollars in support of the school.19

The citizens of New Haven had other ideas. At a meeting on September 10, the mayor and aldermen resolved that a black college would be “destructive of the best interests of the City,” and that, since slavery did not exist in Connecticut, and the college tacitly supported the immediate emancipation of slaves, a black college represented “an unwarrantable and dangerous interference with the internal concerns of other States.” Abolitionists had miscalculated. They had selected New Haven because of the “friendly, pious, generous, and humane” residents of the town and were mortified by the way in which “a sober and christian community … rush[ed] together to blot out the

first ray of hope for the blacks.” The hypocrisy about not interfering with internal concerns was galling. After all, these same citizens sent flour and supplies to support revolutionaries in Poland, and evinced outrage over Georgia’s treatment of the Cherokee Indians, yet themselves treated free blacks with the same disdain. A “Dialogue in Two Acts,” printed in the New-Haven Register, exposed the contradictions:

FRIEND: Have you heard the Georgians are driving off the Indians?

PUBLIC SPIRIT: Yes! And my blood boils with indignation at the deed … . It is astonishing that in this christian country, the precepts of religion and humanity are so grossly violated … . Let us declare in the face of the world that we wage eternal war against ignorance and oppression … .

FRIEND: Have you heard of the proposition to establish a College in this place for the improvement of the colored youth? …

PUBLIC SPIRIT: Colored youth! What do you mean, Nigger College in this place! … Have you lost your senses! … Give a liberal education to a black man! Look at the consequences! Why the first thing he will do when educated will be to run right off and cut the throats of our Southern brethren; or if he should stay among us he will soon get to feel himself almost equal to the whites … . Send them off to Africa, their native country, where they belong.20

Samuel J. May, Unitarian minister in Brooklyn, Connecticut, and contributor to The Liberator, warned of the consequences of such prejudice. He despaired that whites were “shamefully indifferent to the injuries inflicted upon our colored brethren” and declared that “we are implicated in the guilt” of the slaves’ oppression. Arguing that “men are apt to dislike most those whom they have injured most,” he concluded that the intensity of racial prejudice was deepened “by the secret consciousness of the wrong we are doing them.” “The slaves are men,” alerted May. “They are already writhing in their shackles,” he observed on July 3, and will “one day throw them off with vindictive violence.”21

Among the many subjects broached in the pages of The Liberator in its first months of publication, slave insurrections received special attention. The focus of discussion was a brief work published by David Walker in the fall of 1829 and now in its third printing: Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World. Walker had been born free in North Carolina, part of a growing, mainly urban, community of artisans, day laborers, and farmhands whose freedom dated from a spate of manumissions that followed the American Revolution. He traveled throughout the South and North before settling in Boston in the 1820s. He lectured against slavery, joined the Massachusetts General Colored Association, and served as local agent for Freedom’s Journal and Rights of All, black papers published in New York. The Appeal took the form of a preamble and four articles.

Walker began by declaring, “We (colored people of these United States) are the most degraded, wretched, and abject set of beings that ever lived since the world began.” Rejecting all gradual, ameliorative approaches to slavery, he appealed directly to his race: “Brethren, arise, arise! Strike for your lives and liberties. Now is the day and the hour.” “When shall we arise from this death-like apathy?,” he asked, “And be men!!”

Walker refuted Thomas Jefferson’s racial beliefs as expressed in Notes on the State of Virginia. According to Walker, Jefferson believed “it is unfortunate for us that our creator has been pleased to make us black,” but “we will not take his say so, for the fact.” He implored all people of color to challenge Jefferson’s judgment by showing they were men, not brutes, and by demonstrating that “man, in all ages and all nations of the earth, is the same.” The way to accomplish this was by escaping the state of ignorance in which they were kept, by overturning the tenets of slaveholding religion for a gospel of equality, and by adhering to the words of the Declaration of Independence even if white Americans would not. Sounding both millennial and revolutionary chords, Walker alerted Americans, “Your DESTRUCTION is at hand.”

Southerners sought immediately to suppress the publication and

circulation of the Appeal, which nonetheless made its way into Southern ports, carried by black sailors and ship’s stewards who had been approached by antislavery agents in Boston Harbor. One bemused writer in North Carolina found it odd that, “when an old negro from Boston writes a book and sends it amongst us, the whole country is thrown into commotion.” State legislatures met in closed session and passed laws against seditious writings and slave literacy. Across the South, prohibitions on slaves’ reading, writing and preaching were enacted. The mayor of Savannah asked the mayor of Boston to arrest Walker, and newspapers reported prices as high as ten thousand dollars on the author’s head. Walker perished in 1830 under mysterious circumstances. One writer, “a colored Bostonian,” had no doubt that Walker was murdered, a casualty of “Prejudice—Pride—Avarice—Bigotry,” a “victim to the vengeance of the public.” 22

In the second issue of The Liberator, Garrison condemned Walker’s call for violence. Garrison believed in the Christian doctrine of nonresistance, that evil should not be resisted by force; moral, not violent, means would transform public opinion and bring an end to slavery. “We deprecate the spirit and tendency of this Appeal,” he wrote. “We do not preach rebellion—no but submission and peace.” And yet, while proclaiming that “the possibility of a bloody insurrection in the South fills us with dismay,” he averred that, “if any people were ever justified in throwing off the yoke of their tyrants, the slaves are that people.” Garrison also observed, “Our enemies may accuse us of striving to stir up the slaves to revenge,” but their false accusations are intended only “to destroy our influence.”

In the spring, Garrison published an extensive three-part review of the Appeal by an unidentified correspondent. The writer acknowledged that Walker was an extremist, but denied reports that the pamphlet was “the incoherent rhapsody of a blood-thirsty, but vulgar and ignorant fanatic.” Quoting at length from the text and approving Walker’s analysis, the correspondent proclaimed that insurrection was inevitable, justifiable, even commendable. He recalled:

A slave owner once said to me, “Grant your opinions to be just, if you talk so to the slaves they will fall to cutting their master’s throats.”

“And in God’s name,” I replied, “why should they not cut their master’s throats? … If the blacks can come to a sense of their wrongs, and a resolution to redress them, through their own instrumentality or that of others, I shall rejoice.”23

When word of Turner’s revolt came, Garrison did not rejoice, but neither did he denounce. “I do not justify the slaves in their rebellion: yet I do not condemn them … . Our slaves have the best reason to assert their rights by violent measures, inasmuch as they are more oppressed than others.” Noting that the “crime of oppression is national,” he directed his comments to New Englanders as well as Virginians. Indeed, it astonished him that Northern editors opposed to slavery would express support for the South. According to Garrison, Badger’s Weekly Messenger offered the “tenderest sympathy for the distresses” of the slaveholders and the New York Journal of Commerce thought it understandable that “under the circumstances the whites should be wrought up to a high pitch of excitement, and shoot down without mercy, not only the perpetrators, but all who are suspected of participation in the diabolical transaction.”24

Among those “suspected” of inciting the slaves to revolt was Garrison himself. Within several weeks of the insurrection, Southern editors were seeking information about the dissemination of abolitionist literature. The Richmond Enquirer asked its readers to “inform us whether Garrison’s Boston Liberator (or Walker’s appeal) is circulated in any part of this State.” The Vigilance Association of Columbia, South Carolina, offered a fifteen-hundred-dollar reward for the arrest and conviction of any white person circulating “publications of a seditious tendency.” In Georgia, the Senate passed a resolution offering a reward of five thousand dollars for Garrison’s arrest and conviction. The National Intelligencer reprinted a letter claiming that The Liberator was published “by a white man with the avowed purpose of inciting

rebellion in the South” and was carried by “secret agents” who if caught should be barbecued. Northern editors also evinced hostility and pledged “to suppress the misguided efforts of … short-sighted and fanatical persons.” Garrison began receiving “anonymous letters, filled with abominable and bloody sentiments.” He published some of the letters in The Liberator on September 10. One slaveholder, writing from the nation’s capital, warned Garrison “to desist your infamous endeavors to instill into the minds of the negroes the idea that ‘men must be free.’” The prospect of martyrdom only deepened the activist’s resolve: “If the sacrifice of my life be required in this great cause, I shall be willing to make it.”25

The attention turned out to be a boon for the fledging Liberator, and Garrison used it to promote the paper and the cause. Those who had never heard of him now wondered about this Boston abolitionist. “A price set upon the head of a citizen of Massachusetts,” he cried. “Where is the liberty of the press and of speech? Where the spirit of our fathers? … Are we the slaves of Southern taskmasters? Is it treason to maintain the principles of the Declaration of Independence?” Subscriptions to The Liberator, limited largely in its first months to free blacks in Boston, now extended to New York and Philadelphia. Garrison used the momentum created by his success at the business of reform to call a meeting in November that consolidated the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts under his leadership. The constitution of the New-England Anti-Slavery Society (1832), a predecessor to the American Anti-Slavery Society (1833), declared its objective “to effect the abolition of slavery in the United States, to improve the character and conditions of the free people of color … and obtain for them equal civil and political rights and privileges with the whites.” Had Southerners ignored the Boston weekly, it might have folded or limped along. But the attention it garnered in the form of accusation boosted circulation, brought in revenue, and provided Garrison with the platform he desperately sought. “The tread of the youthful Liberator,” he thundered in October, “already shakes the nation.”26

As to the charge of inciting the slaves to murder, Garrison proclaimed

that The Liberator “courts the light, and not darkness.” He reminded readers that he was a pacifist whose creed held that violence of any kind for whatever reason was contrary to Christian precepts. With typical sarcasm, he retorted that if Southerners wanted to prohibit incendiary publications they should ban their own statute books and issue a warrant for Thomas Gray, whose pamphlet on Nat Turner “will only serve to rouse up other leaders and cause other insurrections.” The blow for freedom, he explained, originated in experiences, not words on the page: “The slaves need no incentives at our hands. They will find them in their stripes—in their emaciated bodies—in their ceaseless toil—in their ignorant minds—in every field, in every valley, on every hill-top and mountain, wherever you and your father have fought for liberty.” Garrison likened Turner to other revolutionary leaders: “Although he deserves a portion of the applause which has been so prodigally heaped upon Washington, Bolivar, and other heroes, for the same rebellious though more successful conduct, yet he will be torn to pieces and his memory cursed.”27

Garrison was not alone in viewing Turner’s revolt as part of a transatlantic revolutionary movement. “The whole firmament,” he believed, “is tremulous with an excess of light.” In 1830 and 1831, across the Western world, blows for freedom were being struck. The Belgians obtained independence. In France, the king fled. The British Parliament debated the Reform Bill. In Poland, the Diet declared independence. David Child, the editor of the Massachusetts Journal, proclaimed “that the oppressed and enslaved of every country, Hayti and Virginia as well as France and Poland, have a right to assert their ‘natural and unalienable rights’ whenever and wherever they can.” “These are the days of revolutions, insurrections, and rebellions, throughout the world,” declared a New York editor. And yet “do we hear any portion of the American press rejoice at the success of the efforts of the enslaved AMERICAN to obtain their liberty—mourn over their defeats—or shed a solitary tear of sympathy and pity for their misery, unhappiness, and misfortune?” The writer denounced the hypocrisy of those who “rejoice at the success of liberty, equality, justice,

and freedom, or mourn and sympathize at its defeat abroad,” yet say nothing of its course at “home.” By their actions, “some of the enslaved population of free America … have declared their independence.” Had the writer known that Turner originally planned to strike on the Fourth of July, he would have had even more evidence for his analysis.28

The Free Enquirer, published in New York by Robert Dale Owen, the son of the famous utopian planner Robert Owen, also warned the slaveholders of the fate that awaited them in trying to resist the spirit of the times. Southerners might “suppress partial insurrections; by shooting and hanging, they may for a time intimidate and check that reforming and revolutionizing spirit which has always been extolled when successful; but a knowledge of the world’s history, and man’s nature should teach them that there is a point beyond which oppression cannot be endured, and they ought to anticipate the horrors of the oppressor when that day shall come.” 29

Southerners could not tolerate such talk. “Has it come at last to this,” lamented Thomas Dew of the College of William and Mary, “that the hellish plots and massacres of Dessalines, Gabriel, and Nat Turner, are to be compared to the noble deeds and devoted patriotism of Lafayette, Kosciusko, and Schrynecki?” Dew and others placed the blame for the Southampton County tragedy on the mischievous effects of Garrison’s Liberator and Walker’s Appeal, not on a transatlantic revolutionary ideology of rights and liberties. Southerners sought a simple explanation for a tragedy they could not comprehend in any other way, because to do so would challenge the basis of Southern society. If slavery was wrong, if slaves were human, if liberty belonged to all and at some level every enslaved person knew it, then widespread rebellion and death would mark the future of the slaveholding states.30

The publication of incendiary publications raised another issue as well: the relationship of North and South under the federal government. Garrison often noted that “the bond of our Union is becoming more and more brittle” and thought “a separation between the free and slaves States” to be “unavoidable” unless slavery was speedily abolished. Governor John Floyd of Virginia reached similar conclusions for

different reasons. In his diary on September 27, he wondered how it was possible that no law could punish the editor of The Liberator and other “Northern conspirators” who displayed “the express intention of inciting the slaves and free negroes in this and the other States to rebellion and to murder the men, women and children of those states.” “A man in our States,” he concluded, “may plot treason in one state against another without fear of punishment, whilst the suffering state has no right to resist by the provisions of the Federal Constitution. If this is not checked it must lead to the separation of these states.”31

Travelers to America in 1831 offered their own thoughts on the future of the United States and the dilemma of slavery in a republic that espoused freedom. James Boardman, an Englishman who left Liverpool in 1829 and returned in the summer of 1831, called America “the El Dorado of the age,” a country “in which the great problem, can man be free, has been triumphantly solved.” Boardman, for one, was reticent on the subject of slavery. While noting that he never hesitated to denounce the institution whenever “opportunities presented themselves,” he expressed satisfaction that slave owners seemed reluctant to use the word “slave,” substituting instead the word “servant” so as to avoid opprobrium. Another Englishman, the barrister Godfrey Vigne, sailed from Liverpool for New York on March 24, “alone, unbewifed, and unbevehicled … with the determination … of seeing all I could of the United States in the space of about six months.” His brief comments on slavery are contradictory, a mirror of the tensions in the air. The slaves, he states, “are a very happy race,” yet “they do as little as they can for their masters” and, if educated, would not “remain long in a state of bondage.” Commenting on the aftermath of Turner’s insurrection, Vigne noted that the Southern threat to secede would be checked by “the danger they would incur from their inability to defend themselves against their black population.” “There can be no doubt,”

he predicted, “that the slaves, with an offer of liberty, would prove a most formidable weapon in the hands of an enemy.”32

Other travelers offered more pointed denunciations of American slavery. In a letter written the day before Christmas, Henry Tudor, also an English barrister, described the horrors of the New Orleans slave market, where he witnessed “about thirty of my fellow-creatures—men, women, children, and even infants at the breast—put up indiscriminately to auction, and knocked down to the highest bidder, just like pigs or oxen in a market.” “It was perfectly disgusting,” he decried, “to observe the different purchasers … feeling their joints and examining their bodies, to ascertain if they were sound and in good wind. Several of them, in no delicate manner, as you may suppose, actually opened the mouths of some of these wretched victims of the white man’s inhumanity, to satisfy themselves as to the soundness of their teeth, and possibly as to their age, as if they had been so many horses in a fair.”

Sold for fourteen hundred dollars were a young man, wife, and infant, “a picture that would have softened a heart of stone”; sold for seven hundred was an attractive eighteen-year-old girl; sold for a thousand was a handsome man of twenty, “almost as white as myself.” “Such a display as this, in a country declaring itself the freest in the world,” Tudor asserted, “presents an anomaly of the most startling character; and as long as so foul a stain shall tarnish the brightness of American freedom, this otherwise prosperous, powerful, and highly civilised country, must be content to forego its proud claims to superior advantages over the rest of mankind.”

For all his indignation, Tudor could not bring himself to advocate immediate abolition. Calling slavery “a subject surrounded by great and numerous difficulties,” he concluded that “an indiscriminate course of emancipation would become a curse to the slaves themselves.” He thought that slaves had to be prepared for freedom, educated in duties and obligations, and that only an act of gradual emancipation, completed with “the present generation of parents passing away,” would protect the republic from convulsion.33

Of all the English travelers, Thomas Hamilton, who sailed from

England in the fall of 1830 and returned the following summer, offered the most biting condemnation of American slavery. Hamilton also witnessed a slave auction in New Orleans, and he recounted the sale of an emaciated woman evidently dying of consumption:

“Now, gentlemen, here is Mary!”, said the auctioneer, “a clever house servant and an excellent cook. Bid me something for this valuable lot. She has only one fault, gentlemen, and that is shamming sick. She pretends to be ill, but there is nothing more the matter with her than there is with me … .”

Men began feeling the woman’s ribs and asking her questions.

“Are you well?” asked one man.

“Oh, no I am very ill.”

“What is the matter with you?”

“I have a bad cough and pain in my side.”

“How long have you had it?”

“Three months and more.”

The auctioneer interrupted: “Damn her humbug. Give her a touch or two of the cow-hide, and I’ll warrant she’ll do your work.”

Mary sold for seventy dollars. Buyers joked that the woman would soon be food for land crabs, and “amid such atrocious merriment the poor dying creature was led off.”

Scenes such as this one passed daily throughout the nation. Slavery, Hamilton noted, extended across “the larger portion of the territory of the Union.” Especially galling was its perpetuation in Washington, where slaves served as waiters, coachmen, servants, and artisans. “While the orators in Congress are rounding periods about liberty in one part of the city, proclaiming, alto voce, that all men are equal, and that ‘resistance to tyrants is obedience to God,’ the auctioneer is exposing human flesh to sale in another.” “That slavery should exist in the District of Columbia,” thundered Hamilton, “that even the foot-print of a slave should be suffered to contaminate the soil peculiarly consecrated to Freedom, that the very shrine of the Goddess

should be polluted by the presence of chains and fetters, is perhaps the most extraordinary and monstrous anomaly to which human inconsistency—a prolific mother—has given birth.”

For those who excused the evil by stating that Americans had inherited the institution from the British, Hamilton had a piercing response: “Now when the United States have enjoyed upwards of half a century of almost unbroken prosperity, when their people, as they themselves declare, are the most moral, the most benevolent, the most enlightened in the world, we are surely entitled to demand, what have this people done for the mitigation of slavery? What have they done to elevate the slave in the scale of moral and intellectual being, and to prepare him for the enjoyment of those privileges to which, sooner or later, the coloured population must be admitted? The answer to these questions unfortunately may be comprised in one word—NOTHING.”

As for the abolition of slavery in the Northern states, Hamilton expressed disdain. “Slavery has only ceased in those portions of the Union, in which it was practically found to be a burden on the industry and resources of the country,” he argued. “wherever it was found profitable, there it has remained, there it is to be found at the present day, in all its pristine and unmitigated ferocity.” Because Northern abolition came gradually, slave owners had time to sell their most valuable property to the South. As a result, when the “day of liberation came, those who actually profited by it, were something like the patients who visited the pool of Bethesda,—the blind, the halt, the maimed, the decrepit, whom it really required no great exercise of generosity to turn about their own business, with an injunction to provide thereafter for their own maintenance.”

Freedom, proclaimed Hamilton, entailed more than liberation from the power of compulsory labor: “If the word means anything, it must mean the enjoyment of equal rights, and the unfettered exercise in each individual of such powers and faculties as God has given him.” Free people of color, he observed, “are subjected to the most grinding and humiliating of all slaveries, that of universal and unconquerable prejudice. The whip, indeed, has been removed from the back of the

Negro, but the chains are still on his limbs, and he bears the brand of degradation on his forehead. What is it but the mere abuse of language to call him free … . The law, in truth, has left him in that most pitiable of all conditions, a masterless slave.”

The condition of free blacks served to highlight further the disingenuousness of slaveholders who pretended to acknowledge the evils of slavery but did not care at all about the fate of the black race. Southerners tried to disarm critics by inviting them to suggest a plan of abolition, to offer a “glimmering of light through the darkness by which this awful subject is surrounded.” But if the slaveholders favored abolition, observed Hamilton, it was “abolition of a peculiar kind, which must be at once cheap and profitable; which shall peril no interest, and offend no prejudice; and which, in liberating the slave shall enrich his master.” Hamilton concluded by wondering how long the slave owners “can hold out against nature, religion, and the common sympathies of mankind … . My own conviction is, that slavery in this country can only be eradicated by some great and terrible convulsion. The sword is evidently suspended; it will fall at last.”34

Some travelers who admired the South (one writer called New Orleans “one of the most wonderful places in the world”) decried state laws that prohibited anyone from teaching slaves to read. In his Guide for Emigrants, J. M. Peck declared that “to keep slaves entirely ignorant of the rights of man, in this spirit-stirring age, is utterly impossible. Seek out the remotest and darkest corner of Louisiana, and plant every guard that is possible around the negro quarters and the light of truth will penetrate. Slaves will find out, for they already know, that they possess rights as men.” The slaves, Peck predicted, were “prepared to enter into the first insurrectionary movement proposed by some artful and talented leader.”35

Rumors of widespread insurrections flowing from Turner’s revolt seemed to substantiate these travelers’ observations. Reports of a rebellion in Raleigh, North Carolina, led authorities to arrest every free black in the city. In Fayetteville, Tennessee, citizens believed they discovered a plot by a group of slaves to set fire to several buildings

and, during the confusion, “seize as many guns and implements of destruction as they could rescue and commence a general massacre.” James Alexander, another of the British travelers who toured America in 1831, noted in his Transatlantic Sketches that in New Orleans “there was an alarm of a slave insurrection … . Hand-bills of an inflammatory nature were found, telling the slaves to rise and massacre the whites; that Hannibal was a Negro, and why should not they also get great leaders among their number to lead them on to revenge? That in the eye of God all men were equal; that they ought instantly to rouse themselves, break their chains, and not leave one white slave proprieter alive; and, in short, that they ought to retaliate by murder for the bondage in which they were held.”36

A German immigrant, twenty-five-year-old Johann Roebling (who would go on to build the Brooklyn Bridge), also heard rumors that in New Orleans “the blacks … had made a plan to massacre the whites, and thus attain their freedom by force.” Roebling restated in his own words what seemed to him the common wisdom of the day: “All reasonable Americans agree … that slavery is the greatest cancerous affliction from which the United States are suffering.” He arrived in Philadelphia on August 6 and immediately began contemplating where to settle. Of one thing he became certain: “We have made our decision to settle in a free state.” “We have been frightened away from the South,” he confided, “by the universally prevailing system of slavery, which has too great an influence on all human relationships and militates against civilization and industry.” Fearing that in time “we should see ourselves compelled to hold slaves,” Roebling headed west from Philadelphia and settled outside of Pittsburgh, where, from a distance, he could “wish the blacks all good fortune in their endeavors to be free.”37

Two other travelers considered the problems of slavery and race in America; unlike others, they continued to contemplate the issues once they returned home. Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave Beaumont, twenty-five and twenty-nine years of age, were court magistrates under Charles X and opponents of Louis-Philippe’s rise to the throne in the

revolution of July 1830. Although hostile to the new king, the young magistrates took an oath of allegiance and then sought an honorable way to wriggle out of their low position in the regime. They asked for leave to visit America to examine the prison system and report back. They hoped not only to fulfill a desire to visit North America, but also to restart their careers by becoming experts on penal discipline and by playing a role in the reform of the justice system in France. The compatriots left Le Havre on April 2 and, after a voyage that early on left Tocqueville “sick and depressed” but Beaumont “well and cheerful,” they arrived in New York thirty-eight days later. In letters written shipboard, they disclosed their intentions to extend their investigation into nothing less than the nature of America and republican government itself and revealed the analytical mind-set for which they would long be remembered. Tocqueville, for example, contemplated life on a ship, where “the necessity of living on top of each other and of looking each other in the eye all the time establishes an informality and a freedom” unknown elsewhere. “This is the true land of liberty,” he proclaimed, “but it can only be practiced between four wooden planks, there’s the difficulty.” Unlike other travelers, who came simply to praise or damn, Tocqueville and Beaumont came to understand. They wrote letters, kept diaries and journals, conducted interviews, and, in an attempt to explain America, published works that combined philosophy, history, sociology, and fiction.38

A consensus emerged from the many conversations Tocqueville recorded in his notebook: Americans increasingly viewed slavery as an evil, but almost no one thought blacks and whites could live together peaceably. Calling slavery “the one great plague of America,” a Georgia planter told Tocqueville, “I do not think that the blacks will ever mingle sufficiently completely with the white to form a single people with them.” In Maryland, John Latrobe, son of the famed architect, proclaimed, “The white population and the black population are in a state of war. They will never mix. It must be that one of the two will surrender the ground to the other.” Joel Poinsett, a South Carolinian and former minister to Mexico, thought it “an extraordinary thing how

far public opinion is becoming enlightened about slavery.” While acknowledging that the idea of slavery as “a great evil” had been “gaining ground,” Poinsett also asserted that plans to buy the slaves and transport them elsewhere were impracticable and extravagant. “I hope the natural course of things will rid us of the slaves,” he confessed, but what that course was he could not say. On October 1, Tocqueville interviewed John Quincy Adams. He asked the former president, newly elected to Congress, whether he viewed slavery “as a great plague for the United States.” “Yes, certainly,” answered Adams. “That is the root of almost all the troubles of the present and fear for the future.” The lawyer Peter Duponceau, who had settled in America during the Revolutionary War, painted the darkest picture: “The great plague of the United States is slavery. It does nothing but get worse. The spirit of the times works towards granting liberty to the slaves. I do not doubt that the blacks will all end by being free. But I think that one day their race will disappear from our land … . We will not get out of the position in which our fathers put us by introducing slavery, except by massacres.”39

Added to what Tocqueville and Beaumont heard was what they saw. Prejudice and segregation permeated the states, free as well as slave. In Massachusetts, free blacks had the rights of citizenship, “but the prejudice is so strong against them that their children cannot be received in the schools.” At the Walnut Street prison in Philadelphia, Tocqueville noticed “that the blacks were separated from the whites even for their meals.” Beaumont attended the theater and was “surprised at the careful distinction made between the white spectators and the audience whose faces were black.” “The colour white is here a nobility, and the colour black a mark of slavery,” he wrote his brother. On October 29, they attended the horse races in Baltimore. A black man, “having ventured to come on to the ground with some whites,” received “a shower of blows with his cane without that causing any surprise to the crowd or to the Negro himself.” Of all the scenes touching on race that they witnessed, the most horrible occurred on November 4 at the Baltimore Almshouse. There they

encountered “a Negro whose madness is extraordinary.” A Baltimore slave trader, notorious for his cruelty, brutalized not only the body of the enslaved, but in this case the mind as well. “The Negro,” Tocqueville recorded, “imagines that this man sticks close to him day and night and snatches away bits of his flesh. When we came into his cell, he was lying on the floor, rolled up in the blanket which was his only clothing. His eyes rolled in their orbits and his face expressed both terror and fury … . This man is one of the most beautiful Negroes I have ever seen, and he is in the prime of his life.”40

Neither Tocqueville nor Beaumont had come to America to study race, but race forced itself on the sympathies of the travelers and figured prominently in their writings once they returned to France. Tocqueville concluded the first volume of Democracy in America (1835) with an essay on “The Present and Probable Future Condition of the Three Races That Inhabit the Territory of the United States.” Reflecting upon his journey and synthesizing his experiences, Tocqueville offered a somber assessment of race in the United States. “The most formidable of all the ills that threaten the future of the Union,” he began, “arises from the presence of a black population upon its territory.” Slavery, he reported, seemed to be receding, but “the prejudice to which it has given birth is immovable … [and] appears to be stronger in the states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists; and nowhere is it so intolerant as in those states where servitude has never been known.” Blacks and whites were separated in theaters, hospitals, churches, even cemeteries, where the “distinction of condition prevails even in the equality of death.” A free person of color “can share neither the rights, nor the pleasures, nor the labor, nor the afflictions, nor the tomb of him whose equal he has been declared to be; and he cannot meet him upon fair terms in life or in death.”41

Tocqueville gave little credence to the argument that enlightened attitudes had precipitated the abolition of slavery in the North. Rather, the small number of slaves and their nonessential role in the Northern economy facilitated emancipation. Moreover, the gradual abolition of

slavery in the North led to a double migration as slaves were shipped south and immigrants flooded Northern cities. In places such as New York, concluded Tocqueville, abolition “does not set the slave free, but merely transfers him to another master, and from the North to the South.” Of the remaining free blacks, segregation and diminishing numbers as a percentage of the population meant that emancipation posed little danger and the freedmen who remained in the North had time to learn “the art of being free.”

“The art of being free.” The phrase encapsulated Tocqueville’s understanding, and he applied it not only to blacks but to whites as well. Struck by the differences between Kentucky and Ohio—the one a slave state, the other free—with the two separated only by a river, Tocqueville observed, “Slavery, which is so cruel to the slave, is prejudicial to the master.” He offered a reading of American character based on the “different effects of slavery and freedom.” In Kentucky, the presence of slavery degraded work and made free men idle and enervated, “ignorant and apathetic”; in Ohio, where slavery did not exist, “active and enlightened” laborers worked for prosperity and improvement. Kentuckians contented themselves with what they had; Ohioans struggled to get more, “to enter upon every path that fortune opens to [them].” Slavery undermined the work ethic and led inhabitants to live in the world of today; freedom exalted it and spawned the energy and enterprise that led to tomorrow. No wonder, he noted, that “it is the Northern states that are in possession of shipping, manufactures, railroads, and canals.” In December 1831, while in Cincinnati, Tocqueville observed, “Slavery threatens the future of those who maintain it, and it ruins the State; but it has become part of the habits and prejudices of the colonist, and his immediate interest is at war with the interest of his own future and the even stronger interest of the country … . Man is not made for slavery; that truth is perhaps event better proved by the master than by the slave.”42

Slavery would be abolished; about that much Tocqueville was fairly certain. But he was at a loss to understand how blacks and whites could ever live together in the South. “We do not know what to do with

the slaves,” a Louisville merchant told him, and that problem perplexed Tocqueville, who, early in his visit to America, confessed to “wearing myself out looking for some perfectly clear and conclusive points, and not finding any.” Along with most Americans, Tocqueville assumed that the races could not coexist. Gradual emancipation schemes that liberated future generations could not succeed, he argued, because such laws would “introduce the principle and the notion of liberty into the heart of slavery … . If this faint dawn of freedom were to show two millions of men their true position, the oppressors would have reason to tremble.” Furthermore, emancipating the slaves without providing for their survival, leaving them in “wretchedness and ignominy,” would only worsen the condition of the freedmen. “The very instruments of the present superiority of the white while slavery exists”—control of land, wealth, and arms—exposes the former slave “to a thousand dangers if it were abolished.” Following emancipation, “the Negroes and the whites must either wholly part or wholly mingle,” but Tocqueville had already concluded that prejudice and inequality made the latter impossible. If the races “do not intermingle in the North of the Union, how,” he wondered, “should they mix in the South?” Yet emancipating and removing the black race, as some advocated, was impossible. The cost of purchasing and transporting some two million slaves exceeded the revenues of the federal government. Such a scheme “can afford no remedy to the New World.”43

Tocqueville despised slavery, but he did not believe slaves could be emancipated without being prepared for freedom. A conversation with Sam Houston on a steamboat headed for New Orleans compelled Tocqueville to think about the differences between Indians and slaves. Houston had been governor of Tennessee before temporarily abandoning his political life to live among the Cherokee Nation, where he acquired an Indian wife and a Cherokee name meaning “the Raven.” He was traveling to Washington along with a delegation to appeal to Andrew Jackson on behalf of the Southeastern tribes, who were being compelled to abandon their ancestral lands. Houston himself was in the midst of abandoning his life among the Cherokee for a career that

would lead him to fame in Texas. When Tocqueville asked Houston about the “natural intelligence” of Indians, the Southerner answered, “I do not think they yield to any other race of men on that account. Besides, I am equally of the opinion that it is the same in the case of the Negroes. The difference one notices between the Indian and the Negro seems to me to result solely from the different education they have received.” Born free, the Indian could act as a free man, with intelligence and ingenuity. But “the ordinary Negro has been a slave before he was born,” and had to be taught how to live as a free man. As a slave owner in Texas, Houston would acquire the reputation of educating his slaves, but he never emancipated them. 44