A man in a daydream drifts toward the precipice of Niagara Falls unaware of the danger. On the opposite side, someone watches. Just as the man is about to plunge, the observer cries out “STOP!” The shout awakens the man from his reverie, and at the critical moment he is saved. A crowd gathers.

“That man has saved my life.”

“But how?”

“O he called to me at the very moment I was stepping off, and that word, STOP, snatched me from destruction. O, if I had not turned that instant, I should have been dashed to pieces. O, it was the mercy of God that kept me from a horrible death.”

Charles Grandison Finney introduced this Niagara Falls parable in a sermon delivered at Boston’s Park Street Church in late October 1831, and he often repeated it to answer the question “What must I do to be saved?” The wandering sinner, Finney suggested, must act immediately in response to the voice of the preacher who shouts the word that originates with God. The sinner must choose salvation. A conversion experience occurs because the preacher is an effective

instrument, the word awakens, and the spirit is present. When all works in unison, the unbeliever is “brought out of darkness into marvelous light.” 1

Finney arrived in Boston at the peak of a revivalist surge that he helped to create and define. In 1831, he later recalled, began “the greatest revival of religion throughout the land that this country had then ever witnessed.” Finney’s rival, Lyman Beecher, who questioned his colleague’s methods and tried to dissuade him from coming to Boston, went further when he declared, “This is the greatest revival of religion that has been since the world began.” The “extraordinary excitement” of evangelical enthusiasm engulfed numerous cities and towns across the United States. In August, the secretary of the American Education Society reported that as many as a “thousand congregations in the United States have been visited within six months … with revivals of religion; and the whole number of conversions is probably not less than fifty thousand.” In New England and the Mid-Atlantic regions particularly, the fires of revivalism burned intensely. Evangelical Protestantism had swept through the southwestern frontier in the first decades of the century, leading to a proliferation of Baptist and Methodist churches. Now Presbyterians and Congregationalists, employing frontier techniques such as prolonged camp meetings and extemporaneous preaching, entered into the competition for souls. Whereas the newer denominations in the South appealed to the poor and dispossessed, those in the North attracted evangelical converts from the middle and upper classes. “The Lord,” Finney proclaimed, “was aiming at the conversion of the highest classes of society.”2

6. “Camp-Meeting,” C. 1829 (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society)

Finney himself was becoming a member of those classes when his conversion came. He was born in 1792 and reared in Oneida County in western New York, an area that would come to be known as the “burned-over district” because the flames of revivalism roared most intensely there. Finney taught for a while in New Jersey and then decided to study for the law. He later claimed that at the time he had had no interest in religion and that he had begun reading the Bible only because his law books contained so many references to the Mosaic Code. One day in the fall of 1821, he took a walk in the woods and suddenly began contemplating the issue of his own salvation. Then and there, in an open space surrounded by fallen trees, he decided to give his heart to God. The struggle with his excessive pride and sinfulness took all day, and he returned to his office to pray. Though the room was dark, it appeared to him as “perfectly light.” At that moment, his religious conversion was completed, and he decided to preach the Gospel. Due in court at 10 A.M., he told his client that he could not handle his case because “I have a retainer from the Lord Jesus Christ to plead his cause.”3

Finney studied theology, and the Oneida Presbytery ordained him in 1824. For the next few years, he led revivals across western New York and Pennsylvania and in New York City. In the fall of 1830, he accepted Rochester as his client. As recently as 1821, Rochester had been a small village of fifteen hundred settlers. The opening of the Erie Canal, which provided access to market for the goods of western New

York, transformed the town. Farmers bought land and devoted their energies to wheat production. Merchants and laborers flooded the city. By 1830, the boomtown had become a bustling entrepôt of ten thousand residents. The boundaries between civilization and the wilderness were so distinct that one visitor commented, “The transition from a crowded street to the ruins of the forest, or to the forest itself, is so sudden, that a stranger, by turning a wrong corner in the dark, might be in danger of breaking his neck over the enormous stumps of trees.”4

But with growth came discord. The middle class divided on political and religious issues and united against the laboring classes on moral questions such as the consumption of alcohol. The story repeated itself in scores of other towns and cities. With expansion and wealth came dissension and strife. Only a revival of religion, many believed, could preserve the nation “from our vast extent of territory, our numerous and increasing population, from diversity of local interests, the power of selfishness, and the fury of sectional jealousy and hate.”5

When the Third Church invited Finney to preach, they were without a minister and embroiled in a controversy with the First Church. “Religion was in a low state,” Finney recalled. His friends advised against going to Rochester: too “uninviting a field,” they warned. He agreed, and prepared to head east from Utica for New York City, a far richer field for someone trying not only to win souls but also to make a career. Upon further reflection, however, he concluded that the reasons “against my going to Rochester, were the most cogent reasons for my going.” With his change of heart, he boarded the canal packet boat with his family and headed west to Rochester, where he filled the pulpit of the Third Church from September 10, 1830, through March 6, 1831.

Finney preached three evenings a week and three times on Sunday. His eyes were irresistible, deeply set and piercing blue; when they fixed on you, it was hard to look away. Hour after hour, day after day, his “clear, shrill” voice pierced the congregation. He spoke without notes, stared into the crowded aisles, and made his case. “It did not

sound like preaching,” recalled one congregant, “but like a lawyer arguing a case before court and jury … . The discourse was a chain of logic brightened by the felicity of illustrations and enforced by urgent appeals from a voice of great compass and melody.” To sway sinners, whom he knew to be particularly anxious about their souls, he reserved an area in front of the pulpit and made certain that ushers led them to these seats. These “anxious inquirers” sat in what was known as the “anxious seat,” and Finney expected them “then and there to give up their hearts.” Considering the social and psychological pressures being applied, it is not surprising that more often than not those at the front publicly renounced their ungodly ways. By the time he left Rochester, some eight hundred residents had converted and joined the churches.6

Finney’s work at Rochester culminated in a Protracted Meeting that lasted five days and blazed from morning to night, while all business in the city was brought to a stop. At the conclusion, Finney was exhausted. Physicians diagnosed him with consumption and advised him to rest. They told him he would not live long. Decades later, Finney chuckled at how the “doctors did not understand my case.” He kept going, and after leaving Rochester, he led a revival in Auburn and then participated in a Protracted Meeting in Providence. The evangelist had his eyes set on Boston, a city crowded with Calvinists (orthodox Presbyterians and Congregationalists) and Arminians (liberal Unitarians and Universalists), the city where Lyman Beecher held sway. For years, Beecher had challenged Finney’s beliefs and methods, claiming that they violated the strictures of Calvinist doctrine: innate depravity, predestination, limited atonement. Although the two had thrashed out their differences at meetings in New Lebanon, New York, in 1827 and Philadelphia in 1828, tensions and suspicions remained. Beecher tried to be diplomatic, telling Finney, “Boston was not the best place of entrance for you into New England,” but Finney knew that Beecher had “solemnly pledged himself to use his influence to oppose me.” The Union Church Committee of Boston decided to send a minister to Rhode Island to hear Finney preach, “to spy out the land

and bring back a report.” But after hearing several sermons, Benjamin Wisner, from Boston’s Old South Church, converted to Finney’s side and embraced the minister. “I came here a heresy-hunter,” he confessed, “but here is my hand, and my heart is with you.”7

Finney arrived in Boston the first week of September and began preaching at the Park Street Church, where Beecher’s son, Edward, was pastor. Toward the end of October, Finney delivered a new sermon, “Sinners Bound to Change Their Own Hearts.” The year and the text were one: Ezekiel 18:31—“Make you a new heart and a new spirit: for why will ye die, O house of Israel?” The sermon encapsulated Finney’s beliefs, displayed his oratorical gifts, and initiated a protracted debate over its meaning. Dispensing with the Calvinist idea of man’s helplessness, Finney proclaimed, “All Holiness … must be voluntary.” How could it be, he inquired, “that God requires us to make a new heart, on pain of eternal death, when at the same time he knows we have no power to obey; and that if ever the work is done, he must himself do the very thing he requires of us.” It made no sense that the sinner was expected to be “entirely passive” in his own salvation, as if waiting for “a surgical operation or an electric shock.” Changing one’s heart was no different from changing one’s mind. The heart was “something over which we have control; something voluntary; something for which we are to blame and which we are bound to alter.” Conversion was the requirement to change our “moral character; our moral disposition; in other words, to change the abiding preference of our minds.” The “actual turning, or change, is the sinner’s own act,” and not “the gift and work of God.” God induces one to turn, but still it must be “your own voluntary act” and it must come now—“another moment’s delay and it may be too late forever.”

Finney offered the Niagara Falls parable and several other stories to illustrate his point. “Tell stories,” Finney advised in his Lectures on Revivals of Religion (1835), “it is the only way to preach.” Here was one key to Finney’s success: his democratic style. He rejected the formality and obscurity of the educated ministry, and his preaching was theatrical, conversational, and practical. He defended his approach

with an anecdote. The bishop of London once asked the actor David Garrick why actors, playing fictional roles, moved audiences to tears, whereas ministers, representing sober realities, were ignored. Garrick replied: “It is because we represent fiction as a reality and you represent reality as a fiction.” Finney made reality palpable and forced congregants to participate in the drama of salvation. He talked in terms well understood by his audience, using analogies to professional ambitions, commercial arrangements, and domestic relations, going so far as to mention “improper intimacy with other women.” The spirit of God was necessary to promote conversion, he reasoned, in the same way that the power of the state was necessary to compel debtors to pay their obligations. The sinner should see himself as a member of a jury who weighs the arguments of the lawyer “and makes up his mind as upon oath and for his life, and gives a verdict upon the spot.”8

As Finney spoke, one man sat scribbling. Asa Rand, Congregationalist minister and editor of The Volunteer, a monthly publication devoted to traditional theology, copied down an abstract of the sermon. He published it, along with critical commentary, and issued his thoughts separately as a pamphlet titled The New Divinity Tried. Rand rejected the theological innovations of the previous decade (variously called New Divinity, New School, or New Haven theology) and remained true to eighteenth-century Calvinist strictures holding that salvation was a gift of divine agency and that regeneration was a physical, not moral, transformation. Rand’s summary read like an indictment. Finney preached “that a moral character, is to be ascribed to voluntary exercises alone, and a nature cannot be either holy or unholy;—that the heart, when considered in relation to God, is nothing but the governing purpose of man;—that the depravity or moral ruin of man has not abridged his power of choosing right with the same ease that he chooses wrong;—and that conversion is effected only by moral suasion, or the influence of motives.”

Simply put, Finney ascribed too much power to the individual and not enough to God. Rand challenged Finney’s parable, arguing, “If the Spirit only cries to the sinner stop, and does not stop him, he will go on

to destruction. If the Spirit only warns, alarms and persuades, the awakened sinner is gone forever.” Conversion and salvation, Rand restated, did not flow from the decision of the sinner and did not come instantaneously, “on the spot.” Regeneration was not a career choice, not “like a man resolving to be a lawyer or a merchant, or changing his purpose about his worldly affairs as people do every day;—changes which might require no sacrifices, no regrets, no self-denial, no surmounting of inward obstacles.” Change came not through choice but entirely through the inaudible, invisible, imperceptible “special agency of the Spirit of God.”9

Rand objected not only to Finney’s doctrines, but also to the measures he employed. Along with other orthodox ministers, he denounced the anxious seat as likely to produce “a selfish or spurious conversion.” Ministers fretted deeply that, “at a time when true conversions are multiplied with such unprecedented rapidity, it is difficult for Christians to detect those which are false.” How to tell the truly penitent from the false had always been a dilemma in Christian theology, but never more so than during a revival that invited sinners to reveal themselves and gave them a platform to enact their conversion. Rather than drawing out genuinely troubled sinners, the anxious seat would likely be filled by “the forward, the sanguine, the rash, the self-confident, and the self-righteous,” not “the modest, the humble, the broken-hearted.” In the hands of Finney, religion had been turned into a “business of self-examination,” in which “conversion is simply an act of will,” based almost exclusively upon a “self-determining power.” Like “the morning cloud and the early dew,” such a faith, Rand predicted, would soon dissipate.10

Rand misjudged. The essence of Finney’s religious belief—indi—vidual action—flooded the American firmament. To be sure, he faced persistent opposition. The orthodox continued to hunt heretics, eventually trying even Lyman Beecher and his son for wandering away from strict religious tenets. In 1836, Finney withdrew from the Presbyterian Church altogether. Denunciation of revivals also rained down from the other side of the religious spectrum, not from Calvinists who denied

free will but from the increasing power of Arminians who reveled in it. In Boston especially this meant the Unitarians, who controlled Harvard, as well as the Universalists. These liberal denominations differed from all Calvinists in their view of doctrinal matters. But, like the orthodox, they decried revivals for the measures employed to win converts: Protracted Meetings, emotional appeals, and uneducated ministers. Revivals, they argued, were being contrived by evangelicals. Women in particular, “young, simple, inexperienced, and uninformed are the very materials suited to the purpose of the actors.” Once converted, they created a “petticoat government in religion.” Speaking at the First Universalist Church in Boston, Walter Balfour snorted that “some clergymen now, can calculate when a revival of religion is to take place, yea, can produce one any time they please. Getting up revivals, is now a thing so well understood, and the means of producing them so well known, that some religious sects, draw their plans, and proceed with such certainty to produce them, as a mason, or a carpenter does to build a house. But an astronomer, though he can calculate to a moment the time of an eclipse, has as yet discovered no measure to produce one at his pleasure.”11

The immediate concern of the Unitarians and Universalists was that, by emphasizing free will and free agency, Finney poached on liberal ground and threatened to increase the power and numbers of what, to them, remained the orthodox party. Revivals, protested one opponent, “are promoted as the last expedient for maintaining the sinking cause of orthodoxy.” Had liberal ministers been able to look past doctrinal and denominational differences, they might have recognized what they shared with the New Divinity ministers: an abiding faith in the power of the individual.12

If Finney led a rebellion against orthodox Calvinism, there also loomed in Boston an incipient rebel against liberal Arminianism—Ralph Waldo Emerson. In February, the twenty-seven-year-old Unitarian minister faced a spiritual crisis when his wife died. “My angel is gone to heaven this morning & I am alone in the world and strangely happy,” he confessed to his aunt. To read Emerson’s journals for the

year is to see how he and Finney, each moving away from starkly opposed religious tenets, galloped in stride: “self makes sin”; “we were made to become better”; “because you are a free agent, God can only remove sin by the concurrence of the sinner.” Emerson shunned the denominations of the day. “In the Bible,” he reasoned, “you are not directed to be a Unitarian or a Calvinist or an Episcopalian.” Denouncing both religious and political strife, he proclaimed that “a Sect or Party is an elegant incognito devised to save a man from the vexation of thinking.” Emerson would emerge out of the “dim confusion” of 1831, resign his pulpit, repudiate “corpse-cold” Unitarianism, and establish himself as the premier philosopher of American individualism in what he called, for better and worse, the “age of the first-person singular.” 13

Finney and Emerson, evangelicalism and transcendentalism, worlds apart yet part and parcel of an American spirit. Reform yourself, they proclaimed, and then reform society. No idea was more important to the day than the belief that man had the power to improve society, perhaps even to perfect it, and in so doing help usher in the millennium. Institutions and behaviors that only a few years earlier had received little notice now became the objects of organized moral-reform efforts: slavery, alcohol, criminality, deviance. Organizations such as the New England Anti-Slavery Society, the American Temperance Society, the Prison Discipline Society, and the Infant School Society competed for membership and funds. Leading ministers, politicians, and social activists frequently joined more than one society, but neither Finney nor Emerson ever embraced organized social activism to the extent of their friends and followers. When they did speak out, they did not go far enough (Finney banned slaveholders from his New York congregation in 1833, but he refused to abolish segregated seating and sought to avoid “angry controversy” on the subject of slavery). Or they regretted it (Emerson delivered a speech and public letter denouncing the removal of the Cherokee from their homeland, but the experience dragged him down “like dead cats around one’s neck”). Compared with denominations, Emerson confessed that he

preferred a “sect for the suppression of Intemperance or a sect for the suppression of loose behaviour to women,” but he never warmed to the idea of organized reform.14

If revivals and reforms disturbed some Northerners, they disgusted at least one Southern visitor to New York. John Quitman, who as governor of Mississippi promoted secession, observed in July from Rhinebeck, New York: “Among the masses in the Northern States, every other feeling is now swallowed up by a religious enthusiasm which is pervading the country. Wherever I have traveled in the free states, I have found preachers holding three, four, six, and eight days’ meeting, provoking revivals, and begging contributions for the Indians, the negroes, the Sunday-schools, foreign missions, home missions, the Colonization society, temperance societies, societies for the education of pious young men, distressed sisters, superannuated ministers, reclaimed penitents, church edifices, church debts, religious libraries, etc., etc.: clamorously exacting the last penny from the poor enthusiast, demanding the widow’s mite, the orphan’s pittance, and denouncing the vengeance of Heaven on those who feel unable to give … . They are not only extortionate, but absolutely insulting in their demands; and my observations lead me to believe there is vast deal of robbery and roguery under this stupendous organization of religious societies.”15

Some men might have mocked and resisted (in Boston, one group posted a broadside for the formation of an “Intemperance Society”), but middle-class women in particular embraced religion and reform. Where women “were most active, revivals were most powerful,” observed one western New Yorker. Women constituted a higher percentage of converts than did men, often joining the church first and then inducing their husbands, sons, and brothers to enlist. Finney’s first convert in Rochester, he recalled, was “a lady of high standing, … a gay, worldly woman, very fond of society,” who renounced “sin, and the world and self.” “From that moment,” he observed, “she was outspoken in her religious convictions, and zealous for the conversion of her friends.” Unlike other ministers, Finney allowed women

equality with men during services by permitting them to pray aloud in mixed gatherings, a practice that scandalized the orthodox. Opponents cried, “Set women to praying? Why, the next thing … will be to set them to preaching.” Finney responded with sarcasm: “What dreadful things,” he mocked. The wife of one pastor summarized one of the ways women believed evangelical religion empowered them: “To the Christian religion we owe the rank we hold in society, and we should feel our obligation … . It is that, which prevents our being treated like beasts of burden—which secures us the honorable privilege of human companionship in social life, and raises us in the domestic relations to the elevated stations of wives and mothers.”16

Bolstered by Christian encomiums, the ideal of domesticity reigned over the middle-class household. One of the best-selling volumes of the year was The Mother’s Book, by Lydia Maria Child. Capitalizing on the success of The Frugal Housewife (1829), Child’s contributions to the advice literature genre added to her growing reputation as a writer of children’s stories and sentimental fiction. “She is the first woman in the republic,” hailed William Lloyd Garrison in 1829. Child despaired over the moral condition of the nation. “If the inordinate love of wealth and parade be not checked among us,” she warned, “it will be the ruin of our country, as it has been, and will be, the ruin of thousands of individuals. What restlessness, what discontent, what bitterness, what knavery and crime, have been produced by this eager passion for money!”

The burden fell to mothers to check the appetites of husbands and children and to use their position to inculcate principles of domestic economy and moral restraint. “What a change would take place in the world if men were always governed by internal principle,” she argued. For women as well as men, all change “must begin with her heart, and religiously drive from thence all unkind and discontented feelings.” Child’s belief that “the mind of a child … is a vessel empty and pure,” to be formed and filled by environmental influences, contradicted Calvinist notions but fit comfortably with the emphasis on individual volition that reached from Finney to Emerson. Child herself moved from Congregationalism to Unitarianism. The “tone of radicalism” perceived

by one reviewer—a tone evident in Child’s contempt for the idleness of the upper classes—became a clarion call when she sacrificed her literary reputation, embraced immediate abolition, and published An. Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans (1833), a work that asked readers to “try to judge the negro by the same rules you judge other men.”17

The question that echoed, like the tolling of the steeple bell, was how to judge one’s self. Henry Ware, Jr., thought he knew the answer, and he explained how in his essay On the Formation of the Christian Character. No other American work articulated the middle-class vision of self as clearly as Ware’s; it passed through at least fifteen editions. Readers, Ware reported, “speak to me of it with tears in their eyes.” The author was a Unitarian minister and professor of pastoral theology, the son of the man whose election as Hollis Professor of Divinity at Harvard in 1805 led orthodox members to resign and establish a more conservative seminary at Andover. Ware’s work sounded again and again the themes of self-denial, self-discipline, and self-improvement. The state of society made individuals “anxious about themselves, about their characters, their condition, their prospects.” Only by “vigilant self-examination,” by replacing external, superficial, public standards for internal, spiritual, private ones, could one obtain a Christian character. This work must be “the business of … life,” because God has opened “a free highway to the kingdom of life, through which all may walk and be saved.” Religion, he claimed, “is a personal thing,” and men “should first and most seriously study its relation to their own hearts.” “Man’s own labors are essential to his salvation,” Ware insisted. Advising Christians to exert themselves immediately in prayer, meditation, and reading, he reminded them, “The work before you is wholly within your power.”18

It is not surprising that orthodox reviewers condemned Ware’s book as “defective” in its religious understanding. “The sinner is directed to be a philosopher,” wrote a bemused Calvinist in Spirit of the Pilgrims, “and by retiring into himself and forming good resolutions” to achieve salvation. But what some found faulty, others found sound.

Ware preached a gospel of self-help that offered a solution to the problems that afflicted Americans: anxiety, ambition, competition, dislocation. Through solitude one achieved “quiet self-possession” and then was suited to enter the public world of business to partake in “secular affairs.” The home, nurtured by women, became sacralized as a haven against the disordering effects of “the distractions of common life.” An emphasis on self-help and individual responsibility also offered a ready explanation for why some succeeded and others failed. The urban laboring classes in particular suffered from long hours, low wages, mounting debts, and increasing poverty and unemployment. The solution to their problems, some argued, rested not with unions, or public relief, or reconfiguring relations between capital and labor, but with the workers themselves. Anyone could rise if he applied himself by gaining an education. At the inaugural Franklin Lectures in Boston, aimed “to promote useful knowledge … among that class from which [Franklin] himself sprung,” the speaker told the assembled laborers and mechanics that “we are all equal” in the ability “to compare, contrive, invent, improve, and perfect.” “It depends mainly on each individual” whether or not he or she advances.19

The laboring classes had their own perspective on the religious and moral enthusiasm that surrounded them. The Working Man’s Advocate denounced the revivals as “a gigantic effort” on the part of “a certain class of theologians … to get power into their hands, to be used for the destruction of our republican institutions.” Citing Jefferson, the paper reminded its readers that, “of all the forms which ambition assumes, the ecclesiastical is the most dangerous.” Particularly upsetting was the movement on the part of evangelicals to prohibit Sunday public activities, such as mail delivery and stagecoach rides, and to introduce religious education into the public schools. If the evangelicals seemed suspicious, the myriad new religious societies germinating from the spiritual preoccupations of the day seemed insane. Most curious of all were the Mormons, led by Joseph Smith, who claimed that he could perform miracles and that angels revealed to him a lost portion of the Bible. Focusing on cooperative enterprise, theocratic rule, and male

authority, the Mormon Church won converts by the thousands. Opponents denounced them as “a strange and ridiculous sect” led by “knaves pretending to have found some holy writings” and peopled by “blind and deluded” followers from “the lazy and worthless classes of society.” One editor condemned the religion as “mental cholera morbus.” In 1831, the Mormons, persecuted in western New York, settled in Kirtland, Ohio, the first stop on a trail west that would eventually lead them to Salt Lake City, Utah. Religious enthusiasms from evangelicalism to Mormonism, concluded the editor of the Working Man’s Advocate, had created not only a class of “fanatics, but lunatics and maniacs” all bent on “enslaving the minds, preparatory to enslaving the bodies, of the rising generation.”20

Questions of religion, gender, and class became linked when the Magdalen Society in New York issued its first report in June. This society, established in 1830, sought to provide an “asylum for females who have deviated from the paths of virtue, and are desirous of being restored to a respectable station in society by religious instruction and the formation of moral and industrious habits.” As its name suggested, the Magdalen Society focused on prostitution and set out to build a “place of refuge” where fallen women could be reformed through religious conversion and education. Arthur Tappan, a wealthy New York merchant who, along with his brother Lewis, supported various reform efforts including the abolition of slavery, presided over the society. The report claimed, “The number of females in this city, who abandon themselves to prostitution is not less than TEN THOUSAND!!” That figure comprised only “public” prostitutes; the figure doubled if one considered the “private harlots and kept misses, many of whom keep up a show of industry as domestics, seamstresses, and nurses in the most respectable families.” These prostitutes, the report insisted, generate six million dollars a year, “a waste of wealth … when weighed beside

the loss of hundreds of thousands of immortal souls.” The author of the report claimed to have a list of names of “the men and boys who are the seducers of the innocent, or the companions of the polluted.” Proclaiming that many of these prostitutes came from the working-class neighborhoods of the city and were “harlots by choice,” the report made clear the society’s objective of succeeding “not merely by rescuing and reforming them, not merely by affording a refuge from misery, but by providing a school of virtue; not simply to destroy the habits of idleness and vice, but to substitute those of honorable and profitable industry, thus benefiting society, while the individual is reclaimed.”

It was the clearest statement of the objectives of evangelical middle-class reform yet written. Substitute for the prostitute the criminal, the drunkard, the pauper, even the slave, and the same formula applied. Not everyone in New York, however, shared the worldview of Tappan and his associates. The public received the report with “unbounded indignation,” denounced it as “grossly revolting and disgraceful,” and declared it a calumny upon the working classes of the city. In addition to newspapers, tracts, and handbills condemning the report, two anti-Magdalen meetings were held at Tammany Hall, and salacious drawings that portrayed Tappan’s “real” interest in prostitution circulated widely. Opponents directed part of their attack against the facts presented in the report, facts that “are nearly impossible to be true.” If the Magdalen Society numbers were accurate, then, based on a population of just over two hundred thousand, “one out of three of the marriageable females of New York at this moment received the wages of prostitution. One out of every six, is an abandoned, promiscuous prostitute … [and] more than half of the adult males, married and unmarried, visit prostitutes more than three times a week!” If, as the report claimed, thirteen million dollars were spent annually on prostitutes, then each male, assuming a fourth of the men between the ages of fifteen and sixty contributed, paid $1,177.68 per year for sexual gratification. Using the word as an adjective rather than a noun, one writer concluded that it was the statistics that were prostitute.21

The Magdalen Society needed such outrageous numbers, opponents

claimed, to bolster their evangelical aims: “Motive is always to be suspected when religion seems to be the real or ostensible one.” The society acted as an auxiliary to “the church and state party” that sought to fuse religion with politics. Those who blew orthodox bubbles did not realize that “fear of punishment in another world has never yet restrained people from the practice of vice in this,” and that the failure of religion to prevent immorality “is the very proof of its inefficiency.” Indeed, corruption progressed most easily under the cloak of religion. In Confessions of a Magdalen, one woman told of being seduced and forced into prostitution by her pastor. “The presence of darkness,” she warned, “sometimes appears as the angel of light.” If these ministers and seminary students who located prostitutes “were as pure and honest as they ought to have been, they could not know anything of this vice.” Wondering about the private asylum planned by the Magdalen Society and echoing fears of conspiracy that ran deep in the American character, one writer inquired, “How is the public to know what is done within these secret walls? What is to prevent it from becoming an engine of religious torture to some?”

Readers found the profiles of the prostitutes as infuriating as the statistical impossibilities and religious homilies of the Magdalen Report. Though conceding that prostitutes came from all backgrounds, the report focused on the working classes as the source of the evil: “Hundreds, perhaps thousands of them, are the daughters of the ignorant, depraved, and vicious part of our population, trained up without culture of any kind, amidst the contagion of evil example, and enter upon a life of prostitution for the gratification of their unbridled passions.” In October, months after the initial controversy, the board of directors of the Magdalen Society issued a second report, in which they acknowledged “inaccuracies” and “ambiguities” in the statistics but reaffirmed the view that the “lower classes crowded together in our cities who come under no favorable moral influence” turn to prostitution.22

If some working-class women turned to prostitution, it was because of economic hardship, not cultural inferiority, responded opponents. Men like Tappan, who shielded themselves behind religious intentions,

actually did more to promote prostitution than abate it. After all, as a leading retailer in the city, he forgot “that his own traffic is the cause, indirectly, of making more prostitutes than all the distilleries in the country.” Instead of “prayers, bibles, and tracts,” why not “afford them the means of an honest living by an honest employment.” At the time the report appeared, the tailoresses of New York went on strike to raise their wages and receive a fair price. The Working Man’s Advocate struggled to awaken interest in the cause of the “oppressed and almost enslaved Tailoresses,” whose condition, “as regards the necessities and comforts of life, is undoubtedly worse than that of the Southern slaves.” Several writers made the connection between the Magdalen Society and the plight of the women workers: “Those who work as tailoresses, are at present standing out for higher wages, in order to prevent being crushed to the earth, sunk to utter degradation. Let this society assist them in their laudable endeavors to get an honest living.” Though the critique of the Magdalen Society as an engine of religious oppression and an elitist assault upon the working classes and urban poor of New York did not win citywide support for the working women, it did have its effect: on December 7, the board of directors of the Magdalen Society voted to cease operations.23

Organized as never before, the working classes sought to advance their interests. Newly formed workingmen’s societies served as self-improvement and self-empowerment associations. In an address at Dedham, Massachusetts, Samuel Whitcomb explained to the audience why farmers, mechanics, and laborers were more useful and important to society than lawyers, merchants, and capitalists. Arguing that the trading and commercial portion of the population constituted one million out of ten, he asked whether this fraction merited its disproportionate control over at least half the property in the nation. “Suppose some providential dispensation should at once remove the whole of this class of persons from our country—would the remaining nine million starve and perish? Would our Republic be brought to an end—our Union be dissolved—our civil institutions be abandoned—our churches and school-houses be shut up, think ye, for the loss of a million

of merchants, lawyers, and capitalists?” Whitcomb then reversed the inquiry: “Suppose all our farmers, and mechanics, and manufacturers, and artisans and labourers, were to be suddenly removed from the country—what would become of the rest? What would … this delicate and enterprising million of people do for food to eat, raiment to put on, dwellings to shelter, fire to warm, and comforts of every sort to cheer them on their journey to heaven?”24

Buoyed by a growing awareness of their power in society, mechanics and laborers formed political parties. In Philadelphia, the party grew out of the Mechanics Union of Trade Associations in 1828. In New York, the Working Men’s Party showed considerable strength in the city elections of 1829. The New England Association of Farmers, Mechanics & Other Working Men was formed at a meeting in Providence in December. For the first time, newspapers devoted to worker’s interest appeared: the Mechanics’ Free Press, the Working Man’s Advocate, the New England Artisan and Farmers, Mechanics, and Laboring Man’s Repository. Every issue of the Working Man’s Advocate—edited by George Henry Evans, a recent British emigrant—carried a list of Working Men’s measures:

EQUAL UNIVERSAL EDUCATION

ABOLITION OF ALL LICENSED MONOPOLIES

ABOLITION OF CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

ABOLITION OF IMPRISONMENT FOR DEBT

AN ENTIRE REVISION OR ABOLITION OF THE PRESENT MILITIA SYSTEM

A LESS EXPENSIVE LAW SYSTEM

EQUAL TAXATION ON PROPERTY

AN EFFECTIVE LIEN LAW FOR LABORERS ON BUILDINGS

A DISTRICT SYSTEM OF ELECTIONS

NO LEGISLATION ON RELIGION

It seems like a motley list, but all lists have their logic, and this one was guided by workers’ fears of the encroachment of power upon liberty.

In its control of laws and elections and institutions, the state held excessive power. And with the power to coerce came the power to imprison, enslave, and execute. Religion, with its strictures and secrecies, posed the greatest threat against liberty. Only education—free, public, universal—offered hope that through knowledge and self-improvement workers could resist the forces of capital that pressed down upon them. In his Working Man’s Manual, Stephen Simpson, a leader of Philadelphia’s labor movement and the editor of the Mechanics’ Free Press, declared that the workers had not yet commenced their own American revolution. “Let the producers of labor but once fully comprehend their injuries and fully appreciate their strength at the polls,” he declared, “and the present oppressive system will vanish like the mists of morning, before the rising sun.”25

Of the various issues identified by the Working Men’s movement, the abolition of imprisonment for debt received the most action, in part because politicians and reformers other than workers found problems and injustices with the practice. “It seems to be now almost universally admitted that the present system imperiously demands a reform,” reported one commentator in the North American Review. The board of managers of the Prison Discipline Society reported the numbers of those imprisoned for debt annually in various states: three thousand in Massachusetts, ten thousand in New York, seven thousand in Pennsylvania, three thousand in Maryland. The majority of these debtors, they found, were imprisoned for trifling sums, often less than five dollars. Of conditions in all the states surveyed, they found “nothing worse, in the whole length and breadth of the land, than in New Jersey,” where a high proportion of debtors languished in filthy facilities and the state spent more than the original debt to recover the debt, while providing no support at all for those in prison—just “walls, bars, and bolts.”

The arguments against imprisonment for debt came from all directions. Some focused on the injustice and inexpedience of the punishment, pointing to the wretched prison conditions and arguing that incarceration would not increase the creditor’s chances of recovering

the debt. Others focused on the paltry sums for which debtors could be confined. In the examinations of the causes of debt, a distinction emerged between fraud and honest debt, the one deserving the harshest penalties and the other deserving sympathy and understanding. “The inability to pay one’s debts is itself no proof of crime,” declared Edward Everett, senator from Massachusetts. “It may, and often does, arise from the act of God, and misfortune in all its forms. A man may become insolvent in consequence of sickness, shipwreck, a fire, a bad season, political changes.” Bad luck, not bad intentions. Stephen Simpson shifted the focus from the honest worker to the despotic capitalist. Since a complaint from the creditor led to the imprisonment of the debtor, the law thereby “invests the creditor with the power over the PERSON, the BODY, and consequently the LIFE of the debtor, who in vain pleads the will to pay, but appeals to God to show that he has no ability to second his will … . Capital and law have usurped a power, contrary to the natural laws of labour, as well as repugnant to the principles of the American Declaration of Independence.”26

A number of states had already instituted changes in the laws governing debtor’s prison (eliminating the jailing of female debtors, raising the minimum amount of debt, compelling creditors to pay an allowance for bread money), but New York went a step further and, on April 26, passed a law abolishing imprisonment for debt. Responding to the governor’s address to the Assembly, in which he proclaimed imprisonment for debt “repugnant to humanity,” legislators prepared a report that recommended abolition. Intentions, they argued, mattered. Not paying a debt afforded “no evidence of moral turpitude or criminal intent, and without such evidence, we have no authority to invade the right of personal liberty.” Imprisonment was an appropriate punishment for fraud, but not for debt. Further, under current laws, the presumption of innocence and the right to a speedy trial before an impartial jury were abandoned in favor of the “presumption of fraud arising in the mind of one individual,” the creditor. The debtor “is put to the torture and starved into a compliance with the wishes or designs of his creditor.” The effect of the punishment in this case was retribution

against an individual, not reformation of a criminal, because “indebtedness is not a crime, … misfortune is not an offence.” Jail serves only to “swell the amount of [the debtor’s] afflictions, and press him more heavily to the earth than before.”

In passing an act that abolished imprisonment for debt as a civil procedure and established guidelines for the criminal prosecution and punishment of fraudulent debtors, the legislature acted on a growing consensus within the community. To be sure, the language of working-class radicalism found its way into the discussion, particularly where the writers of the Assembly report presented themselves as counterweights to the oppression of the poor and the weak by the wealthy and influential: “The cries of the slave will long be heard before the sympathies of the master will be awakened—the voice of the poor is feeble and petitioning, that of the rich, powerful and commanding.” But the creditors also saw their own interests advanced by abolition and a different line of reasoning swayed them. Not only did it cost time and money to pursue debtors, but many of these creditors were themselves in debt to others. Misfortune could visit anyone. It was the responsibility of the creditor to demand some collateral for the debt, because accidents were “among the ordinary occurrences of life.” The creditor “trusted to the good fortune of the debtor as the merchant to the prosperity of the voyage. If the one be unfortunate and the other unsuccessful, the loss must rest where the risk occurred. The debtor promises to pay if he has ability to do so; the creditor agrees to trust to his ability, consequently if the debtor has not the ability to pay, he has not forfeited his promise … . If a man agrees to go to London and dies before he can arrive there, it will scarcely be said he has violated his promise; and is it not equally impossible for a man to pay a debt, when he had nothing wherewith to pay it?”27

The harsh winter in New York made abstract questions of misfortune palpable. Within a week’s span in February, more than three thousand people applied for poor relief. Philip Hone, the former mayor, noted, “The long continuance of extreme cold weather and the consequent difficulty of bringing wood to the city have occasioned great distress

to the poor.” George Evans reported, “Poor creatures are to be seen at every corner, in every alley, shivering with cold and hunger, unable to procure employment, and doomed to utter starvation.” Frozen conditions clotted the commercial arteries of the city and the working classes suffered acutely. Whatever joy the Working Men’s Party felt over the abolition of imprisonment for debt, they lamented the little progress in other areas. The militia system, which required citizens to stop working and turn out for a three-day period every fall or pay a fine, remained intact; a lien law, to protect workers from builders who did not fulfill contracts, was not passed, although procedures for recovery were put into place; an attempt to organize public meetings to call for a ten-hour workday failed. Some workers feared it would lower wages, and others mocked the very idea that the expectation of twelve hours’ labor made the “employer … oppressive and the employed a slave.”

The Working Men of New York, like similar groups in other cities, claimed not to be a political party (“they disclaim connexion and sympathy with all parties, except that great party which includes the nation”), but the factionalism of politics accelerated their demise. Two of the leaders of the movement that emerged in 1829, Thomas Skid-more and Robert Dale Owen, battled each other publicly in 1831 over the question of birth control. The men had already parted ways in their approach to Working Men’s activism. Skidmore, the author of The Rights of Man to Property (1829), called for the abolition of all inheritance laws and the reallocation of wealth. He rejected the concept of private property, seeing it as a violation of natural rights: “Why not sell the winds of heaven, that man might not breathe without price? Why not sell the light of the sun, that man should not see without making another rich?” Whereas Skidmore advocated redistribution, Owen stressed reform. The son of the famous utopian Robert Owen, who created a communitarian society at New Harmony, Indiana, in 1825, Owen came to New York in 1829 from New Harmony and joined Frances Wright, the advocate of free thought and women’s rights, whom he had met two years earlier. They published the Free Enquirer, a

weekly paper devoted to rational inquiry and reform. Unlike Skidmore, who sought equal wealth, Owen and Wright stressed equal education. Sounding as much like middle-class reformers as like working-class radicals, they advocated the creation of nonsectarian state-run schools that would educate all children equally and inculcate the values of industry, temperance, and discipline. It was not that Skidmore did not believe in education, but, as one Owenite put it, “he thinks that if means were equal, education would be universal; I think if right education were universal, means would be equal.”28

Birth control fit into Owen’s education scheme, and he raised the delicate subject in a work that quickly went through several editions, Moral Physiology; or, A Brief and Plain Treatise on the Population Question. It was not a new issue. Political economists and philosophers such as Thomas Malthus and David Ricardo had shocked the post-Enlightenment world by arguing that population increased faster than society’s ability to provide sustenance; as a consequence, poverty and misery, not progress and happiness, would mark the future. Despairing that nations relied upon war, famine, and disease as checks upon unrestrained population growth, Owen sought rational measures that returned autonomy and control to the individual. He spurned celibacy as unnatural and unhealthy. Owen sympathized with the Shakers, a religious sect who had taken vows of celibacy and whose name came from an elaborate dance that was part of their service; he urged, however, that the reproductive instinct need not contribute to misery and profligacy but, rather, that “its temperate enjoyment is a blessing.” Though preferable to a life of dissipation, “a life of rigid celibacy,” Owen proclaimed, “is yet fraught with many evils. Peevishness, restlessness, vague longings, and instability of character are among the least of these.” The key was individual self-control, and Owen advocated “the desirability and possibility” of denial and restraint. Only by self-mastery over his instincts did man distinguish himself from “brute creation” and demonstrate the “power to improve, cultivate, and elevate his nature, from generation to generation.” To restrain population growth further, Owen recommended various measures for preventing

conception—withdrawal, the insertion of a sponge, and the use of a covering. After reading Moral Physiology, one writer exclaimed, “A new scene of existence seemed to open before me. I found myself, in this all important matter, a free agent, and, in a degree, the arbiter of my own destiny.”29

In Moral Physiology Exposed and Refuted, Thomas Skidmore denounced Owen’s proposals as an assault upon the working classes. Owen, in essence, argued that “the gratification of one of the most important appetites of our nature and the consequent production of beings like ourselves is a criminal act with all who have not a certain amount of property, [that] poor men may not have as large families as their wealthy neighbors.” Labeling Owen’s work “morose and chilling” and calling the author an “imposter-reformer,” Skidmore argued that a “life of unremitting toil and poverty is not the consequence of having a large family … . It is the effect, directly, immediately, and wholly, of an unjust and vicious organization of government.” With “meretricious sophistry,” Owen was “guilty of throwing out false lights to decoy the wretched from the discovery of the true remedy of their distresses”: the unequal division of property. “Better, far better, it appears to me,” proclaimed Skidmore, “to set about discovering the means of preventing the existence of enormous incomes, derived from the labor of others … . Destroy this, and it will be a long time before Robert Dale Owen, or any other man, will have any cause to complain of the number of mouths.”30

With the debate over birth control, the Working Men’s movement in New York reached its denouement. At the end of the year, Owen left New York for a journey to Indiana and back. He married, traveled to Europe, and on his return settled at New Harmony. Skidmore, the oldest of ten children, died in 1832 in the cholera epidemic that ravaged the city. Evans maintained his ideals but, by 1833, folded the Working Man’s Advocate “because of insufficient patronage.” Elsewhere, the story was much the same. In Philadelphia, Stephen Simpson discontinued his Mechanics’ Free Press, changed political allegiances, and started the Pennsylvania Whig. Workers in New England, late to organize,

never had as much impact as their brethren did elsewhere. The demise of the Working Men’s movement was symbolized by the closing of the Hall of Science in New York. Established by Wright and Owen when they came to the city, the Hall served as a lecture lyceum, printing office, and lending library for the advance of secular knowledge and free thought. For the price of three cents for men and no charge for women, visitors heard talks on astronomy, anatomy, and perspectival drawing as well as debates on such questions as whether “the light of reason is a trustworthy and sufficient guide to happiness.” But economic reality impinged on the pursuit of knowledge and, in a move that represented the triumph of religious revivalism over radical reform, Owen announced in November that he had sold the Hall to a Methodist congregation.31

As a political party, the Working Men’s movement could not sustain itself. But political frenzy pulsated through the nation like an electrical force. “Party politics and prices current,” lamented Owen, “are the alpha and omega of men’s thoughts.” Most foreign travelers thought it remarkable that Americans agreed on the basic principles of government, but as a result “it was not easy to become master of the distinctions” on which parties rested. “America has had great parties,” proclaimed Tocqueville, “but there are not any more now.” He thought that the Federalists and the Republicans of the Revolutionary era held to high moral principles but he did not recognize in the National Republicans and Democrats, the immediate descendants of these parties, similar virtues. “In the whole world,” declared Tocqueville, “I do not see a more wretched and shameful sight than that presented by the different coteries (they do not deserve the name of parties) which now divide the Union. In broad daylight one sees all the petty, shameful passions disturbing them which generally one is careful to keep hidden at the bottom of the human heart.”32

Whatever one called them—coterie, faction, or party—one group that galvanized American politics was the Anti-Masons, who became the first third party in American history and invented the presidential nominating convention. As their name disclosed, the Anti-Masonic Party set itself against Masonry, a private, fraternal organization that originated in England early in the eighteenth century. At the time of the Revolution, there were some one hundred lodges and several thousand members in America, including Ben Franklin and George Washington. Freemasonry continued to expand as entrepreneurs, professionals, and artisans sought social camaraderie and business connections. In January, the New York Register posited the existence of two thousand fraternities with a hundred thousand members. Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay, among many other leading statesmen, belonged at one time or another to a Masonic lodge. Though its exclusive membership, private oaths, and hierarchical orders may have seemed anathema to republican America, Masonry stirred little controversy until 1826, when one mason, William Morgan, disappeared.

Morgan, a fifty-two-year-old artisan in western New York, had planned to publish a pamphlet, Illustrations of Masonry, that exposed the secret rituals of the Masonic order. Local officials, many of them Masons, used all means possible to prevent publication: they burned down the shop that intended to print it and arrested Morgan, first for theft and then for a small debt that he owed. Morgan was languishing in a chilly prison cell in Canandaigua, New York, when someone paid his debt of $2.69 and carried him off in a carriage. They carried him to Rochester and Lewiston and Fort Niagara and, ultimately, to someplace where secrets are never revealed and silence is permanent.

Investigators never found Morgan’s body. Between 1826 and 1831, New York launched over twenty grand-jury investigations and at least eighteen trials but never secured a conviction. Each indictment and trial served only to inflame passions. It seemed that judges, lawyers, and jurors were all Masons; with each acquittal came a new chorus of denunciation for what could only be seen as a conspiracy against liberty. Masonry became a dividing line in American politics, and local

candidates in New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont, and eventually across New England and the Midwest, gained office by running against the seemingly antidemocratic fraternal organization.

Morgan’s was not the only story that roused suspicions that Masonry was akin to tyranny. The case of Pastor George Witherell, a Mason who sought to leave his Masonic temple, was widely discussed throughout the spring of 1831. A Knight Templar in the Masons, Witherell decided he would no longer attend meetings or abide by the oaths and signs that bound members to each other. One evening while the pastor was away, Lucinda Witherell and her son heard footsteps in the darkened house. “Father, have you got home?” the son called. Suddenly, two men with black silk handkerchiefs covering their faces cried out: “Now you damned, perjured rascal, we will inflict upon you the penalty of your violated obligations.” They seized Mrs. Witherell by the throat, but fled when the son came at them.

Investigations failed to identify the culprits, though most citizens suspected they were two Masons seeking to silence the apostate pastor. Shortly after the incident, newspapers throughout western New York printed a bogus trial transcript that purported to be the testimony of the Witherells before a magistrate. Lucinda comes across as little more than a prostitute, and the pastor incriminates himself in the planning and execution of the assault. The forged transcript outraged the community as much as the original assault. Here was deviousness at its worst, accusing Anti-Masons of feigning the assassination in order to win adherents to their cause. “To what acts of depravity,” people wondered, “will not Masonry descend to be revenged on Seceders?”

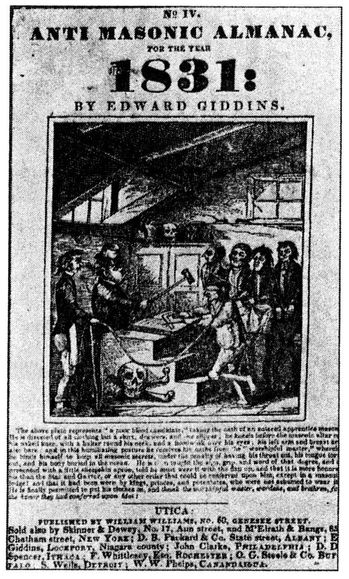

7. Anti Masonic Almanac for the Year 1831 (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society)

Political Anti-Masonry flourished from the cultural anxieties that had been unleashed. In local elections in western New York, Massachusetts, and Vermont, more than 80 percent of the electorate turned out to vote. Anti-Masonic candidates won seats in state assemblies and helped send candidates to Congress. More than a hundred AntiMasonic newspapers sprouted across the nation. With an eye toward nominating a candidate for president, Anti-Masons began soliciting the opinions of leading politicians. Deeming Freemasonry “dangerous to our political and moral welfare,” the Anti-Masonic Committee of Correspondence for York County, Pennsylvania, asked Richard Rush if he was a member. On May 4, Rush, who at various times held the positions of attorney general, secretary of state, minister to England, and secretary of the Treasury, published a response. He offered a lengthy denunciation of the place of secret societies in America:”Of all governments existing, ours is the one, which would be most justified in watching, with constant and scrupulous care, the conduct of societies profoundly secret.” He expressed shock that Morgan’s murderers remained free and outrage”at seeing human life and liberty so sported with, by a power [that] rides in darkness.” “A secret combination,”

capable of thwarting the law, contaminated “the heart of the republic.” Rush condemned the editors of newspapers for failing to uphold the role of a free press “to raise and keep up the alarm.” “Silence,” he believed, “is participation,” but “the press on this occasion has fallen into stupefaction, or turpitude.” Had the press done its duty, “this conspiracy against Morgan would long since have been laid bare, and public justice been vindicated.” Rush concluded by complimenting the Anti-Masonic movement for the efforts they were making against Masonry,”to root out its bad influence from the face of our land.“33

Rush would have made an ideal Anti-Masonic candidate for president, but he privately declined any nomination. John Quincy Adams, the former president who at the end of the year took a seat in the House of Representatives, also entered into Anti-Masonic politics. On July 11, he attended an Anti-Masonic oration at Faneuil Hall in Boston. Lyman Beecher opened the meeting with a prayer, but Adams was struck by how few of his Boston friends were in attendance, evidence of how Anti-Masonry brought new faces into the political arena. Adams declared that he would not take part in the next presidential election but acknowledged that “the dissolution of the Masonic institution” was the most important issue facing “us and our posterity.” In September he allowed a series of letters against Masonry to be published, and for several years he continued to decry the institution. He even ran as Anti-Masonic candidate for governor of Massachusetts in 1833. As a “zealous anti-mason,” Adams made his position clear: because of the atrocious crimes committed in the Morgan affair, it was the duty either of every Masonic lodge to dissolve itself or of respectable Masons to repudiate all “vices, oaths, penalties and secrets.”34

Throughout the winter of 1830—31, state conventions elected delegates to attend a national Anti-Masonic convention in Baltimore in September. One skeptic observed that the meetings, filled with delegates from the burned-over districts where Anti-Masonry had first ignited, resembled revivalist gatherings: “They all become fanatic or like all new converts manifest an extraordinary degree of Zeal—They break at once from all political ties & associations.” “Disclaiming all

association with Jacksonism and Clayism,” with the Democrats and the National Republicans, Anti-Masons decided to build on their success in local elections and nominate candidates for president and vice-president of the United States. “The course we espouse,” declared delegates at the Massachusetts Anti-Masonic convention, “has been driven by necessity to the BALLOT BOX.”35

On September 28, on a motion from Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, delegates nominated William Wirt of Maryland for the presidency. But the nomination did not come easily. Stevens had zealously supported Supreme Court Justice John McLean, who toyed with the idea of accepting the nomination before finally turning it down. McLean’s refusal, recalled William Seward of New York, “fell as a wet blanket upon our warm expectations.” Stevens and Seward roomed together in Baltimore, and the two spent much of the night discussing the nomination. By morning, Stevens had agreed to support Wirt. An exhausted Seward wrote his wife, “If it were an agreeable subject, I would describe to you all the bustle, excitement, collision, irritation, enunciation, suspicion, confusion, obstinacy, foolhardiness, and humor, of a convention of one hundred and thirteen men, from twelve different States, assembled for the purpose of nominating candidates for President and Vice-President of the United States.”36

The attorney general under James Monroe, Wirt was one of the most distinguished lawyers in the nation. Earlier in the year, he had defended a judge in a Senate impeachment trial and had argued before the Supreme Court the case of the Cherokee Indians, who claimed to be an independent nation free from the laws of Georgia. When the nomination came, Wirt was in the midst of a personal crisis, still mourning the death of his daughter from scarlet fever. “The charm of life is gone,” he conceded in March. If running for president did not reinvigorate him, it did provide him with a field for action. In his letter of acceptance, he acknowledged surprise that he had been chosen, ratified the principles of the party, and confessed something that not everyone knew: he had been a Mason. Wirt said he had always regarded Masonry as “nothing more than a social and charitable club,” and only

recently had come to be persuaded that it was a “political engine … at war with the fundamental principles of the social compact.” If anything, public confession and conversion made him that much more appealing, and his candidacy went forward.37

Wirt’s nomination received mixed reviews in the party press. “His conversion to anti-masonry was remarkably sudden,” snorted the New York Evening Post (a pro-Jackson paper), “almost coeval with his nomination to the Presidency.” Another editor accused the Anti-Masons of hypocrisy and “sinister motives.” National Republicans denounced Wirt as ambitious and unscrupulous and joked that Anti-Masons offered him the nomination only after trying everybody else, including Justices John McLean and John Marshall, John Quincy Adams, Daniel Webster, and Richard Rush. But the New Jersey Journal of Commerce (an anti-Jackson paper) thought Wirt had “all the talents and all the qualifications necessary to make a splendid President.” Wirt knew the price he would pay for running: “I shall be laughed out, abused, slandered.” But he also knew who he was. “I am perfectly aware,” he told his friend Salmon Chase (who would seek the Republican nomination for president in 1860), “that I have none of the captivating arts and manners of professional seekers of popularity. I do not desire them. I shall not change my manners; they are a part of my nature. If the people choose to take me as I am—well. If not, they will only leave me where I have preferred to be, enjoying the independence of private life.”38

Wirt had only two years to enjoy that life; he died in 1834. In the election of 1832, he garnered fewer than thirty thousand votes, winning only Vermont and its seven electoral votes. For the most part, the Anti-Masonic moment had passed. Some denounced Anti-Masonry along with Masonry: “I renounce Anti-Masonry,” proclaimed one writer, “because anti-masons are doing precisely what they condemn in the Masonic fraternity: namely, attempting to engross power and office.” One Mason associated Anti-Masonry with a leveling spirit loose in the land, and he urged caution: “A strong and deep-moving excitement is, at this time, shaking the whole earth; and, in a fearful paroxysm, is madly grasping at us. In either hemisphere are observable

the strife of passion, and the thirst for aggrandizement and power, as well as the struggle for freedom and the searching for light. We see systems, institutions, and governments, honored and made venerable by time, and, to human view, fixed and changeless as the sun, in a moment swept away by the tide of popular power.” Most voters silently agreed with one working-class advocate who thought it absurd to believe that “all evils which afflict human nature are of masonic origin.” “To attempt to establish a political creed upon Anti-Masonry,” he reasoned, was “like turning a sugar loaf upside down and expecting it to stand on the smaller end.” “Twenty years hence,” he predicted, “the citizens of these States will have half forgotten that there ever was such a thing in the world of politics as an Anti-masonic excitement.”39

Seward left the convention realistic about Wirt’s chances and the fate of Anti-Masonry. On the steamboat to New York, an accident occurred that moved him to deeper reflections than politics. A man fell overboard. “There was a fearful moment of uncertainty as to who it might be,” confided Seward to his wife. “If every passenger on board the boat thought and felt as I did, he thought only of that person, nearest and dearest to himself, who was among the passengers. Tedious minutes elapsed until it was known. I cannot describe to you the intense, painful anxiety that bound in silence all the crowd, which looked upon the man, as he seemed to stand erect in the water, waiting, and waiting, and waiting for the boats to approach him. What a possession is human life, to be exposed to such hazards; and what must have been the solicitude of that poor mortal, while the boats were getting toward him! And yet, had he sunk beneath the waves, to rise no more, what would it have been but hastening for a few days, or months, or years, a catastrophe which is inevitable; and how very soon would the surface of human society, momentarily agitated by the event like the face of the waters disturbed by his struggle, have become smooth and borne no trace of the commotion!”40

Seward returned home safely and watched as the National Republicans, following the example of the Anti-Masonic Party, held a convention in Baltimore on December 12 and nominated Henry Clay for

president. The smooth-talking, slaveholding Kentuckian had served in the House from 1811 to 1825, and as secretary of state under Adams. One traveler described him as “tall and thin, with a weather-beaten complexion, [and] small gray eyes.” Elected to the Senate in November, Clay had been implored to stand with the Anti-Masons. A fusion of Anti-Masons and National Republicans seemed undefeatable against a wobbly Jackson administration. But Clay refused to make any public statement on the issue. “I tell them,” he said, “that Masonry or Anti-Masonry has, legitimately, in my opinion, nothing to do with politics.” Clay recognized that with Anti-Masonic support, which would deliver New York, Pennsylvania, and Vermont, he would secure the presidency, and he recognized that the two parties agreed on “every thing the general Government can or ought to do.” They differed only on Masonry, but that difference was enough. Clay, seeing himself as planet rather than satellite, felt “we ought to draw them to us, instead of being drawn to them.”

The National Republican convention concluded with an address to the people of the United States. In reviewing Jackson’s administration, delegates proclaimed, “The political history of the Union for the last three years exhibits a series of measures plainly dictated … by blind cupidity or vindictive party spirit, marked throughout by a disregard for good policy, justice, and every high and generous sentiment, and terminating in a dissolution of the Cabinet, under circumstances more scandalous than any of the kind to be met within the annals of the civilized world.” Citizens from every region should vote against Jackson because of his “inconsistent and vacillating” positions. How, for example, wondered the Republicans, could the president “be regarded at the North and West as the friend of the Tariff and Internal Improvements when the only recommendation at the South is the anticipation that he is the person through whose agency the whole system is to be prostrated?” A year earlier, voters were reminded, Jackson had vetoed as unconstitutional the Maysville Road Bill, which would have provided funds for construction of a highway in Kentucky, Clay’s home state. Jackson had also pledged himself against the Bank of the United

States, “this great and beneficial institution,” six years before the issue of renewal was even to emerge before Congress. If the president was re-elected, warned National Republicans, “it may be considered certain that the Bank will be abolished.” Jackson’s behavior as president seemed so tyrannical that, by 1834, the National Republicans renamed themselves the Whigs, after the English party that had traditionally opposed the excesses of the monarchy.41

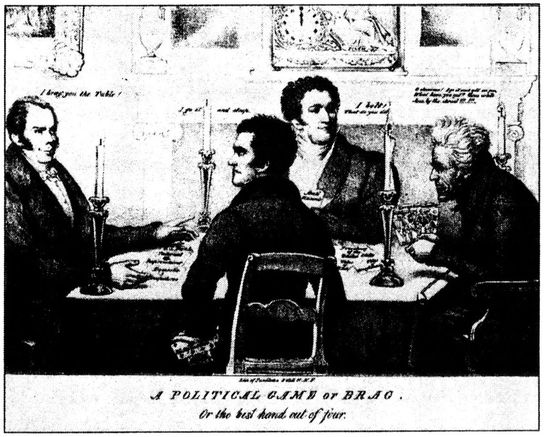

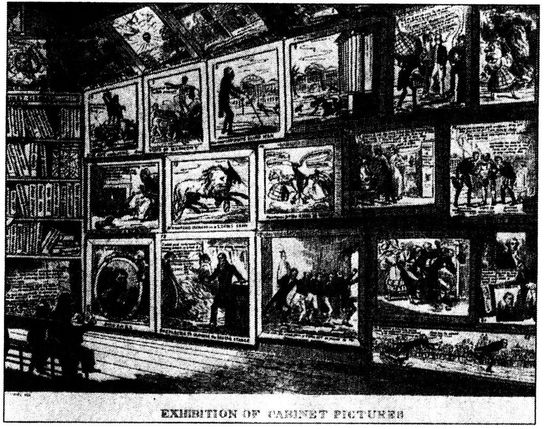

In addressing such issues as the tariff, internal improvements, and the Bank, the convention identified a cluster of policies at the core of the National Republican belief system, policies they believed would carry them to the White House. A pro-Clay cartoon depicted the candidate as playing a card game against his leading political opponents. His hand of three aces, which features the economic policies advocated by Clay, defeats William Wirt’s Anti-Masonic card, John C. Calhoun’s hidden hand of nullification and antitariff, and Andrew Jackson’s three kings of intrigue, corruption, and imbecility. At stake is the presidency of the United States. Supporters heralded Clay as the father of the “American system,” a shorthand name for those measures endorsed by the party. Protective tariffs, National Republicans claimed, supported domestic industry against foreign imports; investments in roads, canals, and, most recently, railroads created a transportation infrastructure that promoted commerce; a national bank provided a uniform currency and regulated credit. As a consequence of these measures, all sections of the nation had prospered, and the United States had emerged as an international power.

8. “A Political Game of Brag” (Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society)

The system, Clay believed, sustained both slaveholding and non-slaveholding states; as if to bolster his point, he even argued against introducing any schemes of gradual emancipation in Kentucky. Clay’s first oration before the Twenty-second Congress, delivered over several days in February 1832, defended the economic principles on which he had staked his career: “This transformation of the condition of the country from gloom and distress to brightness and prosperity, had been mainly the work of American legislation, fostering American industry … . There is scarcely any interest, scarcely a vocation in society, which is not embraced by the beneficence of this system.” The American system, he asserted, benefited not just a single state or a region but “the whole Union.”42

By invoking the Union, Clay echoed the sentiments of another leading national republican, Daniel Webster, who was elected to the House from Massachusetts in 1822 and the Senate in 1827. Webster had gained fame as a lawyer and orator; when he was firing at full throttle, one observer noted, “his power is majestic, irresistible.” On January 26, 1830, he reached the capstone of his career. A Senate debate with Robert Hayne of South Carolina had started over the sale of public lands and ended with a discussion of the tariff, slavery, states’ rights, and the nature of the Union itself. The Constitution, he argued, was not created by the states but “made for the people, made by the people, and answerable to the people.” Webster concluded with a paean to American nationalism: “When my eyes shall be turned to

behold for the last time the sun in heaven, may I not see him shining on the broken and dishonored fragments of a once glorious Union; on States dissevered, discordant, belligerent; on a land rent with civil feuds, or drenched, it may be, in fraternal blood! Let their last feeble and lingering glance rather behold the gorgeous ensign of the republic, now known and honored throughout the earth, still full high advanced, its arms and trophies streaming in their original lustre, not a stripe erased or polluted, not a single star obscured, bearing for its motto no such miserable interrogatory as ‘What is all this worth?’ nor those other words of delusion and folly, ‘Liberty first and Union afterwards’; but everywhere, spread all over the sea and over the land, and in every wind under the whole heavens, that other sentiment, dear to every true American heart,—Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!”43

The speech made Webster a hero among National Republicans and a household name throughout the nation; its echoes would sound in an address delivered at Gettysburg more than three decades later. Always ambitious, the senator considered a run for the presidency. He thought it increasingly possible that Jackson would not be re-elected and believed the prospect of electing Clay “not promising.” And although Anti-Masonic sentiment was gaining, Anti-Masonry as a political party did not offer “a principle broad enough to save the Country.” The key, he felt, was to unite the Anti-Masons and National Republicans behind a candidate who, in the election of 1832, could secure New York and Pennsylvania. Webster undoubtedly thought of himself as that candidate, and his performance at a public dinner in New York on March 24 served to test political waters.44

Before 250 guests, the commercial and mercantile elite of New York, Webster spoke for an hour and a half. Once again, he defended the Constitution and the nation. He praised Hamilton, Jay, and Madison, the authors of The Federalist Papers, and he credited the principles of the American system for New York’s emergence “as the commercial capital, not only of all the United States, but of the whole continent:” Webster anointed America a place of “refuge for the distressed

and the persecuted of other nations.” But he warned that the nation “can stand trial, it can stand assault, it can stand adversity, it can stand every thing, but the marring of its own beauty, and the weakening of its own strength. It can stand every thing but the effects of our own rashness and our own folly. It can stand every thing but disorganization, disunion, and nullification.”45