Although it entered service only a few months before the much more modern Hawker Hurricane, the Gladiator was in many ways a development of the Gloster Gauntlet biplane fighter and was considered by some to be the pinnacle of the biplane fighter concept. Gloster submitted the design to the Air Ministry in 1935, and the first production variants were delivered in February and March of 1937. Powered by an 830hp Bristol Mercury radial engine, the Gladiator Mk II, which was in service by the beginning of the war, was capable of speeds in excess of 400km/h (250mph), with a range of some 700km (440 miles). It was armed with four .303in. Browning machine guns, two carried underneath the lower wings and two mounted to each side of the engine. With its enclosed cockpit and automatic mixture control, the Gladiator did possess some modern features. Many pilots noted its exceptional handling characteristics and near perfect harmony of controls. However, as a fixed undercarriage biplane it was arguably obsolete when it entered service, particularly when one considers the opposition it would soon encounter. Nevertheless, when facing foes such as the Italian Air Force in North Africa and Malta, the Gladiator performed commendably, with Flt. Lt. ‘Pat’ Pattle claiming 15½ kills in Gladiators, with a further four probables. While popular with its pilots, the Gladiator was unable to contend with modern opposition such as the Bf 109, and was ultimately replaced by the Hurricane and Spitfire, although it continued to fly in communications, liaison and meteorological roles until 1944.

The Gloster Gladiator represented perhaps the ultimate evolution in the design of the biplane fighter, but was outclassed by modern, high-performance monoplanes even before war broke out. (RAF Museum, P006781)

The Blenheim entered service in March 1937 as a light day bomber, stunning the world’s aviation journalists with its modern appearance and features, such as its all-metal construction (apart from its fabric-covered control surfaces), split trailing edge flaps, Frise mass balanced ailerons and a top speed of 450km/h (285mph); it was faster than many fighters of the era. Modified for service as a long-range fighter, the 1F variant was equipped with a tray of four .303in. machine guns in the belly to augment its single .303in. gun turret. However, although the Blenheim’s range of over 1,600km (1,000 miles) made it theoretically useful in its role as a long-range fighter, its cumbersome handling characteristics in comparison to modern, single-engine fighters made it poor in a dogfight, and early clashes left the Blenheim squadrons suffering heavy casualties. More useful were approximately 200 examples that were fitted with pioneering Airborne Interception (AI) radars for use as night-fighters. A Blenheim 1F scored the first AI radar success in combat on the night of 2–3 July 1940, but even with a limited run of more powerful Blenheim IVs converted to the fighter role, the type was not well suited to air-to-air combat and was replaced by more manoeuvrable aircraft such as the De Havilland Mosquito.

With its prototype being capable of reaching speeds far greater than any fighter operated by the RAF when it first flew in 1935, great things were expected of the Blenheim in the opening stages of the war. However, it proved vulnerable to enemy fighters in daylight operations and the 1F fighter variant was restricted to night-fighter duties. (RAF Museum, P001667)

A low-winged monoplane, with retractable undercarriage and an enclosed cockpit, powered by a single Rolls-Royce Merlin engine, the Defiant had all the appearances of a truly modern fighter. However, what separated the Defiant from its contemporaries was its armament: its four .303in. Browning machine guns were packed in a power-operated gun turret fitted behind the pilot’s cockpit. The theory was that placing the guns in a turret gave the aircraft a far greater field of fire, and allowed the pilot to concentrate solely on flying the aircraft, leaving his gunner to aim and operate the weaponry. However, the extra weight and drag imposed by the turret were nothing short of crippling – the Defiant’s maximum speed was only just over 500km/h (310mph) and its manoeuvrability was poor. The Defiant scored notable successes early on in its career, with No. 264 Squadron claiming 65 enemy aircraft destroyed in May 1940. However, once German fighter pilots had stopped confusing this new type with the Hurricane it closely resembled from some angles, they learned that the Defiant could be attacked head-on or from underneath, out of range of its turret guns. In the ensuing dogfights, the cumbersome Defiant was easy prey, and they were withdrawn from daylight operations in August 1940, after suffering disastrous losses. Fitted with AI radar, the type faired far better as a night-fighter, although the Defiant was replaced in this role, too, by faster and more manoeuvrable aircraft, seeing out the rest of its service as a target tug or in the air/sea rescue role.

Nicknamed the ‘Daffy’, the Defiant was a turret fighter, carrying no forward firing guns to be operated by the pilot. The concept of being able to attack formations of unescorted enemy bombers proved unsound, and the Defiant was easy prey for German fighters. (RAF Museum, P014432)

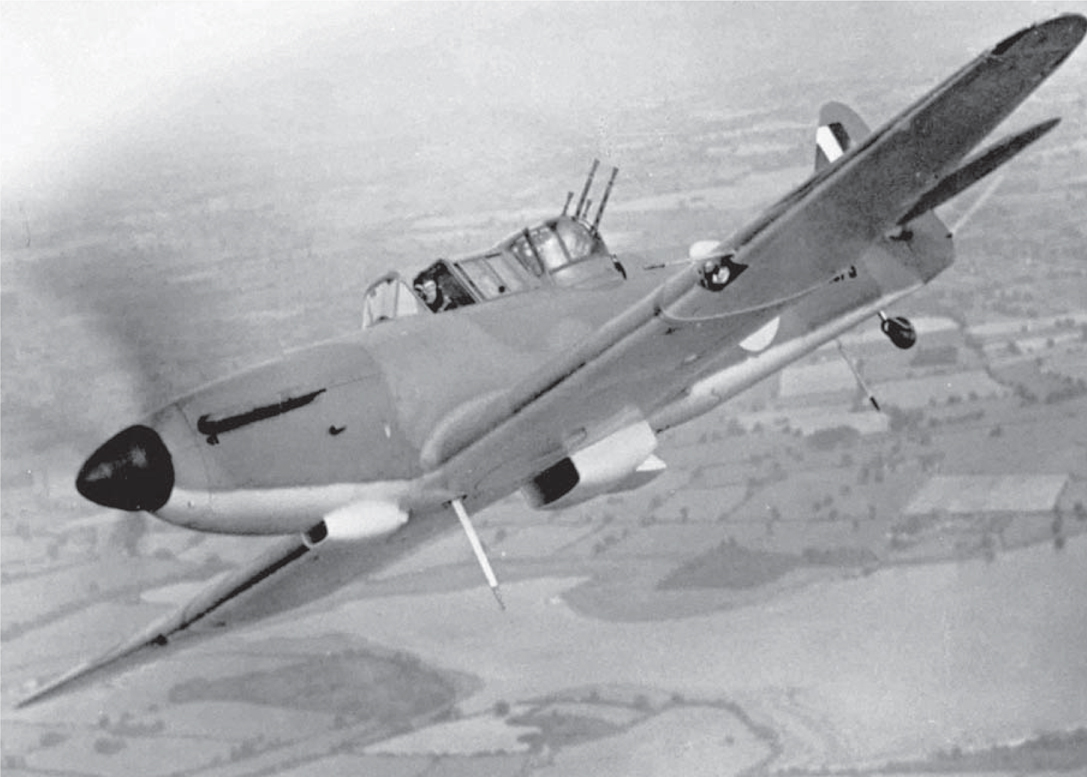

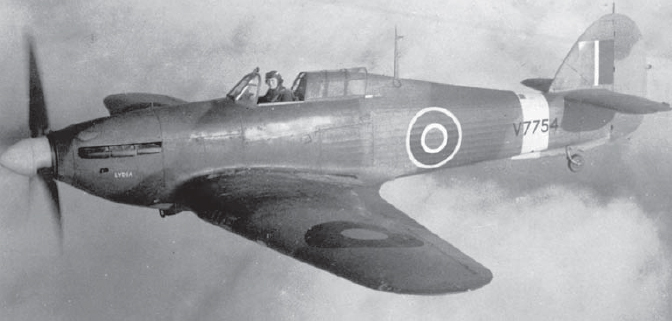

A low-winged monoplane with retractable undercarriage, enclosed cockpit and eight .303in. machine guns, the Hurricane was the RAF’s first truly modern fighter when it entered service in December 1937. Powered by a Rolls-Royce Merlin II engine rated at 1030bhp, the Hurricane Mk 1 was capable of speeds in excess of 520km/h (320mph); the Hurricane’s performance was further improved by the implementation of a variable pitch, three-bladed propeller, which replaced the two-bladed, fixed pitch propeller found on early examples.

At the outbreak of hostilities, 19 squadrons of Fighter Command were equipped with the Hurricane. It was a Hurricane of No. 1 Squadron which became the first RAF aircraft to destroy a German aircraft on the Western Front, when Plt. Off. P. W. Mould claimed a Dornier 17 near Toul on 30 October 1939. Initially, four squadrons of Hurricanes had been sent to France shortly after the outbreak of the war, but this number would double over the next few months. Combat over France would identify several shortcomings in the Hurricane’s performance, and the Bf 109 outclassed it in several key aspects. While the Hurricane was a sturdy machine with a good rate of turn at low altitudes, the Bf 109 was faster, more manoeuvrable and armed with 20mm cannon to augment its 7.7mm machine guns, giving it considerably more punch. However, the Hurricane proved robust in operating from field conditions, and was more than a match for any other German aircraft in theatre. Nevertheless, nearly 200 Hurricanes were destroyed or damaged to the point of having to be abandoned in France, a huge loss for the RAF as it represented nearly a quarter of the front-line strength of Fighter Command. The Hurricane further proved its flexibility and adaptability in the Norwegian Campaign, with men of No. 46 Squadron being the first pilots to launch modern, land-based fighters from the decks of a Royal Navy aircraft carrier (HMS Glorious) and thus proving to the Admiralty that carrier-borne air power need not be confined to lower-performance aircraft. Furthermore, after operating successfully in the harsh climates of Norway, the squadron successfully returned to Glorious for recovery back to Britain. Weights were placed aft of each fighter’s centre of gravity to allow harsher braking upon landing on deck, with less fear of the tail rising, as the land-based Hurricanes were not equipped with arrestor hooks.

By August 1940, Fighter Command could field a strength of 32 squadrons of Hurricanes, compared to 19 of Spitfires. The numbers in which the Hurricane were available made it perhaps the most integral part of Britain’s defence; Hurricanes accounted for more confirmed kills in the summer of 1940 than all other British aircraft and ground defences combined. While the Hurricane did not have the speed and manoeuvrability of the Spitfire, its thicker wing provided a more stable platform for its machine guns, and if both RAF fighters were involved in the same combat it was a common tactic for the Spitfire to engage escorting German fighters, leaving the Hurricane to tackle enemy bombers. It was in August 1940 when Fighter Command won its only Victoria Cross of the war; Flt. Lt. J. B. Nicholson of No. 249 Squadron remained at the controls of his badly damaged Hurricane, sustaining severe burns in the blazing cockpit, to shoot down a Bf 110 before baling out.

The Hawker Hurricane was the first truly effective fighter employed by Fighter Command in the lead-up to World War II. Although not as fast or as manoeuvrable as the Bf 109, it was still a potent fighting machine in the hands of a skilled pilot, and more than able to hold its own in a dogfight. (RAF Museum, P005110)

Hurricane development continued in 1941 with the Mk II, whose Merlin XX engine gave an increase in reliability and power. The IIB was equipped with 12 .303in. machine guns, and could carry up to 225kg (500lb) of bombs. The IIC variant replaced its machine guns with four 20mm cannon, whilst the IID was designed as a tank-buster, with two under-wing 40mm cannon pods. However, although these stages of the Hurricane’s development showed a great versatility of roles, its performance continued to slip further behind that of the latest enemy fighters and its days as a dedicated fighter aircraft were numbered. The Hurricane would go on to serve in many theatres throughout the war, scoring notable successes in the deserts of North Africa and in the defence of Malta. It also performed admirably in ground attack and anti-shipping roles, as a carrier-based fighter with the Fleet Air Arm, and as an export fighter to several Allied nations.

Capturing the imagination and affection of the British public perhaps more than any other aircraft of the era, the Spitfire was, in many ways, the most capable asset available to Fighter Command at the beginning of World War II. The Spitfire first entered service in July 1938, with nine squadrons being operational by the outbreak of the war. Powered by the same Rolls-Royce Merlin II as the Hurricane I, the Spitfire was faster and more manoeuvrable, possessing a performance comparable to the Bf 109. Early Spitfires were fitted with two-blade, fixed-pitch propellers and armed with only four .303in. machine guns, but improvements were quickly introduced, including the fitting of variable pitch propellers, a further four machine guns, bullet-proof windscreens and hydraulically operated wing flaps and undercarriage. The Mk IB experimented with early 20mm cannon, but was withdrawn from service following problems with jamming.

Considered too valuable an asset to be employed in France, Spitfires initially saw far less action than other types in Fighter Command, but it was a Spitfire of No. 603 Squadron that was responsible for the first German aircraft to be shot down over Britain, when a Heinkel 111 was claimed over the Firth of Forth in October 1939. The Spitfire proved itself in combat during the Battle of Britain, where it reached such a state of notoriety amongst German aircrew that some claimed to have been damaged or shot down by Spitfires when it was actually the more numerous Hurricanes which was responsible. This opinion was even echoed at command level; at the height of the battle, when Hermann Göring asked a group of his squadron commanders what they required from him, fighter ace Adolf Galland replied ‘I should like an outfit of Spitfires for my group’, (although he would go on record to say he preferred the Bf 109, which he believed was faster than the Spitfire but less manoeuvrable).

By December 1940, the Spitfire Mk II had achieved operational status; the Mk II was equipped with the slightly more powerful Merlin XII, and a Mk IIB cannon variant which proved barely more successful than its predecessor. This was followed in February 1941 by the next major production variant of the Spitfire: the Mk V. The Spitfire V was strengthened significantly to absorb the power of the new 1,470bhp Merlin 45 engine, and Mk VA retained the same armament as previous models, whilst the far more numerous VB was armed with two 20mm cannon and four .303in. machine guns. A VC was also developed with a universal wing, capable of carrying either the VA or VB armament, or four cannon. The Mk V was also able to carry a drop tank beneath the fuselage to increase its endurance. The Mk V was a significant development from earlier models, now placing a more reliable cannon feed in Fighter Command’s premier fighter aircraft. The Mk VB was also the first Spitfire variant to be released for overseas service, shipped on board HMS Eagle for the defence of Malta in March 1942.

Although less numerous than the Hurricane in the early years of the war, the Supermarine Spitfire captured the imagination of the British public. After the Battle of Britain, the Spitfire continued to develop through a myriad of variants, forming the backbone of Fighter Command in most theatres throughout the war. This Spitfire is a cannon-armed Mk Vb of No. 243 Squadron. (RAF Museum)

However, once the German Focke-Wulf Fw 190 entered service, the Spitfire was placed on the back foot. The Spitfire was forced to undergo constant developments and improvements throughout its operational life, until later marques, equipped with Rolls-Royce Griffon engines, a tear-drop shaped canopy and clipped wings, bore little resemblance to the earliest Spitfires. The RAF’s last operational Spitfire mission was flown in Malaya in April 1954.

Designed as a replacement for the Hurricane, the Typhoon initially entered service in summer 1941, rushed to front-line squadrons in an attempt to counter the threat posed by the new Fw 190. However, the Typhoon was initially plagued with problems. Its Rolls-Royce Sabre engine was unreliable, particularly when starting in cold weather, and its poor exhaust system caused a threat of carbon monoxide poisoning to pilots so severe that they had to wear their oxygen masks immediately upon starting up. Worse still, structural weaknesses in the Typhoon caused by a combination of factors, including harmonic vibration, resulted in instances of the entire tail unit detaching, often in a high-speed dive. These problems were to greater or lesser extents solved or alleviated by a series of modifications, but the Typhoon suffered mixed reviews from those who operated it for the remainder of its service life. However, equipped with four 20mm cannon, a top speed of over 645km/h (400mph) and noted for being a very stable gun platform, particularly at high speeds, the Typhoon did achieve notable successes in combat. It performed admirably in the ground-attack role and as a low-altitude interceptor.

The Beaufighter was based, in part, upon Bristol’s Beaufort torpedo bomber, which in turn also had its roots in the Blenheim. Its wings, control surfaces, gear and part of the fuselage were identical to those of the Beaufort. With the outbreak of hostilities looking all but unavoidable, the Air Ministry was faced with the problem of producing as many fighters as possible in a short time. Intended as little more than an improvised long-range escort fighter/night-fighter, the Beaufighter first flew in July 1939. Powered by two 1,500bhp Bristol Hercules radial engines, the Beaufighter was capable of speeds in excess of 500km/h (320mph) and was armed with four powerful 20mm cannon in the nose, plus four .303in. machine guns in the starboard wing, and two in the port. It became clear in the early stages of the Beaufighter’s life that it had ample room within its fuselage for the cumbersome AI radar kit of the period, and the 1F variant was fitted with the AI Mk IV to be used as a night-fighter.

The first Beaufighter AI kill for Fighter Command was in November 1940, but it was not until January 1941, when partnered with Ground Controlled Interception that the Beaufighter began to excel in its night-fighter role. Having performed well in the Mediterranean and Western Desert, as well as with Coastal Command, the Beaufighter was developed into several variants, with the Mk VI, equipped with more powerful 1,670bhp engines, entering service in 1942. The Beaufighter continued to serve throughout the war, finally being withdrawn from service in 1960 when the last examples had been converted into target-towing aircraft.