As with the majority of branches of the armed forces, the conditions experienced by the pilots of RAF Fighter Command varied hugely, depending on the theatre of war. While the living conditions would never be as hard as those experienced by their brethren in the infantry, front-line life overseas was often far from comfortable, and defending Britain from the well-equipped airfields of the home front still brought its own unique difficulties.

For pilots at the beginning of the war the prospect of being drawn into a conflict not dissimilar to that experienced by their parents’ generation was a very real threat. However, in the opening days of the war very little contact with the enemy actually occurred, giving rise to the term the ‘Phoney War’ to describe these opening rounds. Pilots were still stationed around Britain, with little actual change in their day-to-day routines.

Created by Bill Hooper, Pilot Officer Prune was a cartoon fighter pilot whose escapades and buffoonery were intended to teach valuable lessons to aircrew, in a light-hearted and amusing fashion. (RAF Museum, FA02055)

In September 1939 the majority of Fighter Command’s pilots were based at large, purpose-built RAF airfields, such as Biggin Hill and Tangmere in No. 11 Group in the south-east, and Duxford and Wittering in No. 12 Group further to the north. Squadrons of different commands were kept on separate airfields wherever possible and Fighter Command’s airfields were, owing to the performance of its aircraft, relatively simple compared to those of other commands. Airfields would often be built around four runways, the longest of which would be some 1,200m (1,300 yards) in length, and they were often grass, concrete runways being something of a rarity. Officers were given the option of accommodation in the officers’ mess, although those with families often opted to live off base in their own housing. Accommodation in the mess was also variable, but most pre-war officers’ messes offered single rooms with ablutions, showers and baths provided on each corridor. NCO pilots would likewise live in the sergeants’ mess, their living conditions being slightly more austere than their commissioned counterparts. Large bases also had their own sports facilities, with pitches for football, rugby and cricket, and gymnasiums or tennis and squash courts – these facilities were far too expensive and time-consuming to build in the smaller airfields that were constructed after the outbreak of war.

Food, accommodation and medical and dental care were free; flying clothing was provided free of charge, although officers were expected to pay for their uniforms. The working day consisted of breakfast at one’s respective mess, before being transported over to the squadron building, often on the far side of the airfield from the mess, so as to separate the noisy working areas from the accommodation area of an airfield. Squadron buildings also varied greatly from purpose-built, permanent buildings to hastily constructed Nissen huts, made up of little more than simple brick walls and corrugated iron roofing. Flying consisted of training sorties to keep essential skills current, as well as Air Tests – flying aircraft with recent repairs or maintenance to ensure that they were fully serviceable.

Evenings were often spent in pursuit of the time-honoured interests of young men in the armed forces: drinking and socialising. Alcoholic drinks were on sale in messes, but local pubs or journeys into nearby towns and cities were also popular alternatives for a change of scenery. Formalized rules governing drinking and flying were yet to be instigated, as Flt. Lt. David Price-Hughes recalled:

David was tight [drunk] at a Hunt Ball in which there was a cabaret show. One of the turns was a ventriloquist, whose act was completely ruined because David, despite violent ejection and cautious re-entry through a window, put into the dummy’s mouth language that should not normally proceed from the mouth of babes… Alban… in a similar condition, went into an ice-rink to retrieve a hat. Being skateless he found the surface slippery, and the evening ended with Alban on all fours proceeding rapidly round the rink in one direction, while his fellow inebriates did likewise in the other.

Price-Hughes goes on to describe his feelings towards working with members of the Womens’ Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), at a time when female members of the armed forces was something of a rarity: ‘There are some very pretty WAAFs here, and they are hardworking and uncomplaining. Most of them are from decent families… yet, owing to some stupid regulation laid down by some idiot or idiots unknown… they are not allowed even to speak to the officers… which is damned silly and only serves to focus the attention on them more.’

He summed up the experiences of many RAF pilots in the Phoney War: ‘For us at home, so far, the war has been a little vague, an affair of petty inconveniences, higher prices, blackout… but mostly second-hand news.’

The situation overseas varied markedly from these early war conditions on the home front. With the French Air Force still active, RAF squadrons sent to France were relegated to suitable fields with hurriedly erected facilities to serve as their bases of operations. Flight Lieutenant Price-Hughes recalls his first experiences of France:

The first sight of the French coastline was a thrill which was not lessened by the discovery that we were right on track… the only observable differences were the lack of hedges or any sort of division between fields, and the comparative sparseness of houses and villages… we found it difficult to locate the aerodromes, as they were nothing more than fields: no buildings save a tin hut, the only signs of activity being picketed aircraft. Having delivered our (aircraft)… a ‘bus service’… took us to flight HQ in a village 1½ miles away. Squadron HQ… was 6 miles away in another village. And such a squalid village, tawdry houses, and mud, mud, mud everywhere. Our lunch consisted of bread, butter and cheese which did not suit us at all… 57 squadron told us that they are not popular with the local inhabitants… (they) believe that France is fighting for England, that the war is really for the sake of England… they render all possible assistance, but, as we saw, leave us strictly alone, and show no signs of friendliness.

Relations between French civilians and RAF servicemen supporting the British Expeditionary Force alike were unfortunately often far from cordial, as described by Flight Lieutenant James Patterson, a New Zealander.

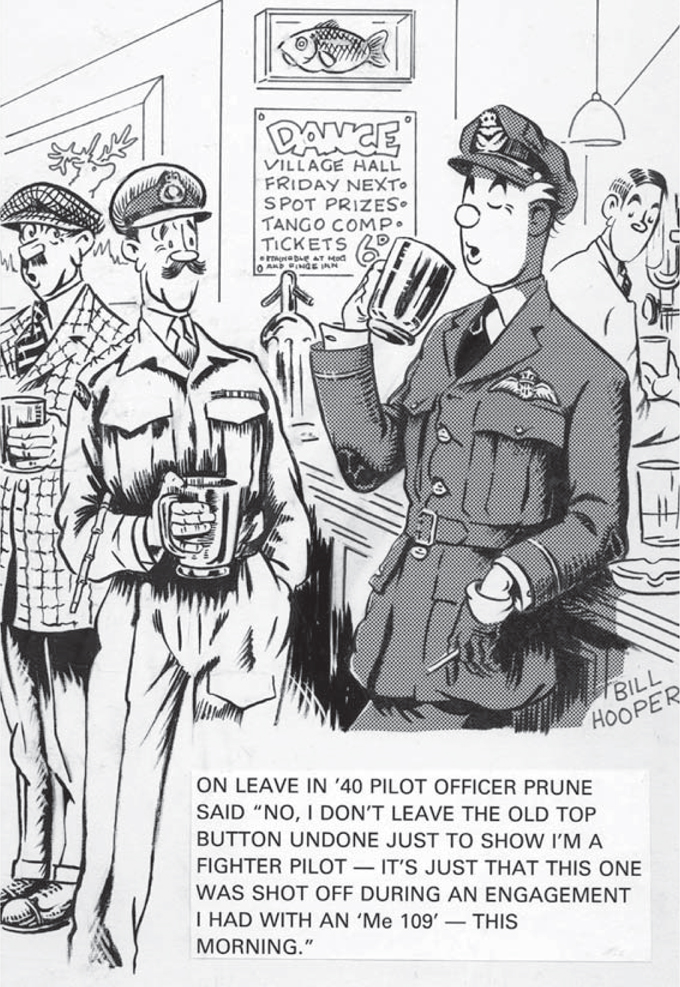

Field conditions experienced at a typical improvised airstrip in France. The Hurricane proved robust and well capable of adapting to the rigors of life in the field, and was popular with its pilots and ground crews alike. (RAF Museum, P001858)

On arriving I did a normal circuit before landing, but noticed everything seemed so deserted until I was taxiing in, then bullets began to come whistling from everywhere about the hangars, and Frenchmen advanced, not content to cover me… but to let go every now and then at the aircraft… I was promptly searched and my revolver taken away, and with some bayonets to my back I was marched into a waiting car, driven off to Rheims and imprisoned in the Palace Royal.

After this misunderstanding was resolved, Patterson was released and returned to his aircraft, only to find one of his ground crew had been shot by a soldier serving in the French army. ‘My fitter [was] groaning like hell… [he] stopped a plug of lead in his arm, a half-caste Moroccan troop did it – I felt so mad that when I got my revolver back I threatened to shoot him; finished by beating him up in front of his Captain, not strictly done but justified.’

However, experiences of France were far from universally negative. Flight Lieutenant David Price-Hughes described his accommodation once his squadron was properly established:

The billet is a farmhouse, with a high wall around, through which one passes by a heavy gateway. Geoff’s room opens off mine, which is large, about 15 feet square, with a dominant light green colour. My bed is of antique design in brass, but comfortable enough, and there is no danger of suffering from cold at night. A built in cupboard, which forms a fine bookcase and wardrobe, a table in the corner on which are two tin bowls and a tumbler, a slop pail, a towel rack, and a larger table on which I am writing from the furnishings of this luxury hotel. The floor is bare, but the boards are polished. Returned to the mess for supper, and as complete sprogs were invited to sit at the CO’s table… there were champagne and Vittel water to drink, and being a teetotaller I took the latter. This was not to the CO’s liking and I was ordered to drink champagne… which I found not unpleasant… it is apparently a standard drink for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

While the pilots of Fighter Command were not living and working in the conditions to which they had become accustomed, there is no doubt that, for the majority of the French campaign, aircrew living conditions were far superior to those of the front-line forces in the army.

However, the conditions experienced by squadrons sent to Norway were considerably harder. After Germany invaded Norway and Denmark on 9 April 1940, No. 46 Squadron’s Hurricanes and No. 263 Squadron’s Gladiators were moved into theatre. As Norway was covered in a thick blanket of snow, the campaign lent itself more to carrier-borne air power, rather than host nation support, but although aircraft of the Fleet Air Arm were heavily involved in the air war it was the high-performance Hurricanes of No. 46 Squadron which could potentially provide the greatest threat to the modern aircraft employed by the Luftwaffe.

|

GLOSTER GLADIATOR IN ACTION, NORWAY, MAY 1940 A Gloster Gladiator II of No. 263 Squadron engage a Heinkel 111 bomber over Norway in May 1940. Prior to deploying to theatre, the squadron should have had its unit identification codes removed from the fuselages of its aircraft for security purposes, but the few surviving photos of the Norwegian campaign show that this was only achieved on some of its aircraft. Number 263 Squadron operated from Bardufoss during late May and early June, with a detachment of two aircraft flying from a hastily prepared landing strip at Bodo. The squadron was involved in almost daily combat, protecting British ground forces from German bombers in poor weather conditions with barely adequate logistical support. Whilst outclassed by German fighters, the nimble Gladiator with its excellent rate of climb and manoeuvrability, proved to be an effective interceptor, and gave a laudable account of itself against enemy bombers and reconnaissance aircraft during the campaign. |

A pilot of No. 263 Squadron is photographed amid bomb damage in Bardufoss, Norway, in May 1940. This was the squadron’s second outing to Norway, having sustained heavy losses the previous month. (RAF Museum, PC73-91-004)

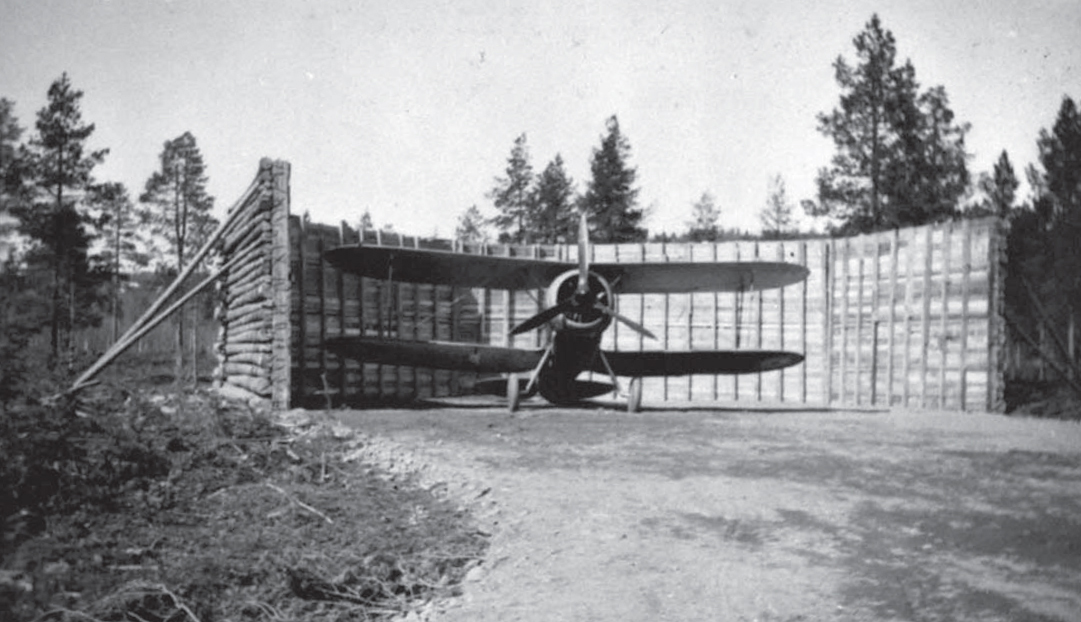

As the country was still covered in a thick layer of snow, finding bases for the RAF fighters was a problem. Improvised airstrips and frozen lakes were all that could be provided, with protection for the aircraft being made up from pens constructed by felled trees. Accommodation for pilots was, as with France, provided by locals, although the relationship with the Norwegians was by and large far more cordial: the RAF squadrons were more dependent on local knowledge and expertise to survive the harsh climate, whilst the Norwegian armed forces were in some ways less capable than those of the French, leading to a greater reliance on each other from both parties, a significant factor towards a better working relationship. The local conditions did lead to their own, unique difficulties – two of No. 46 Squadron’s Hurricanes crashed on landing in Norway after launching from the carrier HMS Glorious because of the soft landing ground, unfamiliar to many British pilots. Simple factors which had been taken for granted, such as keeping roads to and from airstrips clear, now became a full-time job after snowfall.

A work party carrying out road repairs in Bardufoss. Heavy rain as well as snow proved to be a problem in maintaining adequate lines of communications to improvised RAF airstrips, well away from areas of modern infrastructure. (RAF Museum, 006)

A Gladiator Mk II of No. 263 Squadron inside a blast shelter built up of locally sourced timbers. Operating from field conditions, pilots lived and worked in very different conditions to their colleagues in Britain. (RAF Museum, PC73-91-009)

Norwegians help to move a stranded vehicle from No. 263 Squadron. Whilst pilots were subject to working in harsh conditions, they praised the bravery and hospitality of the Norwegian people they worked alongside. (RAF Museum, PC73-91-005)

The move back to Britain following the campaigns in France and Norway certainly provided more comfortable conditions in many cases, but the tempo of operations presented its own problems. As the threat of German invasion was at the forefront of the nation’s collective consciousness, pilots of RAF Fighter Command were now stationed across the entire country, some at main sector airfields, others at the smaller grass strips of satellite airfields. The working routine for pilots was largely similar across all groups. The day began at around an hour before dawn, with pilots having breakfast before being transported to Dispersal – the building which housed them during the working day. By this stage the aircraft had been thoroughly checked by ground crews overnight, and were being run to warm up the engines. Pilots were informed which aircraft was allocated to them for the day, which Section they would be flying in, and with whom. For many squadrons, keeping these parameters as fixed as possible was desirable. Although they all rolled off similar production lines, individual aircraft had unique handling characteristics to which pilots grew accustomed, and working with the same pilots in the same section also bred familiarity, which was vital in combat.

Having been allocated an aircraft and section, pilots would then collect their flying kit and walk out to their aircraft. The modern practice of pilots conducting a detailed walk-around was not carried out; ground crews had already completed pre-flight checks. Great care was then taken in setting out seat and parachute harnesses, and arranging kit efficiently so that take-off was as quick as possible. Oxygen masks and gunsights were also checked, and if the weather had been poor overnight pilots would assist ground crews in polishing the fighter’s windscreen, as good visibility was paramount in air combat.

With the aircraft ready in all respects to scramble, pilots then reconvened at Dispersal. During the height of the battle, time in between sorties was spent playing cards, chess or darts in Nissen huts or outside, reading, or for those who were able to overcome the nerves of waiting to be scrambled, sleeping in chairs or on cot beds inside the huts. The Dispersal telephone became an object of fear; each ring had the potential to be a scramble, but was often something far more trivial or mundane. When scrambles were ordered, the number of aircraft depended on the size of the raid – scrambles could be ordered by sections of three aircraft or flights of six fighters, but were often full squadron scrambles of all 12 aircraft.

|

HAWKER HURRICANE Is, NO. 46 SQUADRON, FLIGHT DECK, HMS GLORIOUS, JUNE 1940 |

| Hawker Hurricane Is of No. 46 Squadron land on the flight deck of HMS Glorious during the early hours of 8 June 1940. This feat was nothing short of remarkable for many reasons – none of the pilots were trained in deck-landing techniques, the aircraft were not fitted with arrestor hooks, a high-performance, land-based fighter of the era had never before been landed on the deck of a carrier, and the light levels were poor, making the whole procedure even more difficult. The Hurricanes were fitted with sandbags aft of the centre of gravity, so that full brakes could be applied immediately upon landing without the tail rising to cause a propeller tip strike on the deck. Squadron Leader Kenneth ‘Bing’ Cross led from the front, attempting the first landing. Referring to the scepticism shown to his pilots by the Royal Navy, he later said, ‘We showed them they were wrong’. The tremendous skill displayed by No. 46 Squadron paid dividends to the Fleet Air Arm, who now had proof that modern aircraft could be operated successfully from aircraft carriers, and the event led directly to the development of the Sea Hurricane. Unfortunately, the success of 8 June was overshadowed by tragedy, when Glorious was sunk the next morning by the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. 1,207 men were lost during the sinking of Glorious, or in the water afterwards, including eight of the ten No. 46 Squadron pilots and ten pilots of No. 263 Squadron. |

A Hurricane destroyed on the ground in France. Anticipating losses, the numerically inferior Spitfires were confined to Britain and kept out of the campaigns in France and Norway. (RAF Museum, PC79-19-749)

After the confusion of combat, squadrons rarely returned in strength to their airfield, as they were likely to have been separated and returned in small formations or individually. Ground crews would eagerly wait for ‘their’ pilot and aircraft to return. If guns had been fired in anger, the tape over the gun ports to stop the guns freezing at altitude would now be torn, causing a distinctive whine of air across the wings as the fighters descended to land. Ground crews would quickly refuel, rearm and top up oxygen on their aircraft, turning them back round and ready to fly again in as little as ten minutes. Meanwhile, pilots would return to the crew rooms at Dispersal for debrief, giving details of any enemy engagements to the squadron intelligence officer. Not knowing when the next opportunity to eat would occur, pilots would often grab food immediately on completion of debriefing, and the squadron would be returned to readiness. The actual degree of readiness varied – if a squadron was ordered to be at five minutes’ readiness, this would necessitate sitting in the cockpits of their aircraft, fully kitted and ready to start engines. The number of scrambles per day varied greatly, but a busy day could involve up to five scrambles, although often some of these could be false alarms or result in no enemy contact for other reasons, such as poor weather or arriving on scene too late.

The pace of operations and the constant waiting for the Dispersal telephone to ring would invariably cause strain on any pilot’s nerves. For the vast majority, the overwhelming importance of the battle and loyalty to one’s squadron mates was more than enough to overcome this fear, but Flt. Lt. Al Deere recalled watches being placed on ‘suspect’ pilots. After the initial attack, when aircraft were scattered in each direction, it was nearly impossible for squadron leaders and flight commanders to observe individual pilots, who, in an act of self-preservation, had the opportunity to flee an engagement. However, while this temptation was understandably strong, by far the greater part of Fighter Command was able to overcome it. Deere commented that the danger was strongest when fatigue allowed self-preservation to overcome the sense of duty.

The dangers of operating continuously at this pace were not lost on Fighter Command; Dowding was keen to allow each squadron one day’s rest per week, but this was not always possible. The sheer pace, exhaustion and rate of casualties is highlighted in a letter by Flying Officer James ‘Jas’ Storrar to his father during the height of the Battle of Britain:

so much has happened I have lost so many friends and been in too much trouble not to be affected by it… 145 Squadron was practically entirely wiped out, we saw the first of the Battle of Britain and in the last 6 days took the brunt of it. You probably read of the squadron that got 21 aircraft in one day, well that was the start for us and it kept on like that until there were only four of us left and one aeroplane, so they decided that we were no longer operational, we dined with Lord Beaverbrook met the Prime Minister talked on the wireless and were finally sent up to a place called Drem in Scotland to recuperate and reform.

Whilst squadrons were rotated wherever possible out of No. 11 Group in the south-east which bore the brunt of the fighting, pilots still needed an escape after the working day which typically ended at around 8pm. Pubs were common for socializing in evenings and for those stationed near large cities, night clubs provided a popular pastime until the early hours before returning to accommodation blocks or messes for a few hours’ sleep before repeating the whole daily routine.

With the onset of autumn in 1940 and the threat of invasion significantly reduced, pilots could settle down into a much more workable routine. The working day now had a later start and an earlier finish, and with the changing role of Fighter Command, including ‘rhubarb’ ground attack missions over occupied France as of December 1940, squadrons could now be more proactive rather than reactive in their planning cycles. Ground attack or escort missions over occupied Europe meant that pilots would now know in advance when they would be flying, leading to working routines which were far more manageable than in the dark days of summer 1940. German raids over the British mainland continued throughout the war, with Fighter Command still using RDF to scramble and intercept incoming raids, but with the more versatile role of the fighter aircraft, and the Luftwaffe changing its concentration of operations to other theatres, pilots of RAF Fighter Command based in Britain between 1941 and 1942 had more favourable working conditions.