BELIEF AND BELONGING

Men from a vast spectrum of differing social backgrounds came together to form the pilot cadre of Fighter Command. The myth that the Battle of Britain was won by a handful of ex-public school officer pilots is a complete fallacy; thousands of pilots throughout the war served in all commands of the RAF as NCOs. Just as there was a myriad of different people entering Fighter Command, so too were the reasons behind enlisting, and the personal motivation for individuals to continue flying operational sorties.

David Price-Hughes, then a pilot officer, went into some detail on his feelings towards war and his reasoning behind joining the RAF in his diary: ‘Although I have neither fixed principles or beliefs, I am nevertheless logically an execrator of war as being the negation of reason, apotheosis of the principle of destruction and evil, and I find it hard, therefore, to explain to others or to myself for what reasons and from what motives I am fighting in this war. That there are things worth dying for I can no longer believe, greatly though I should rejoice to find myself wrong.’

|

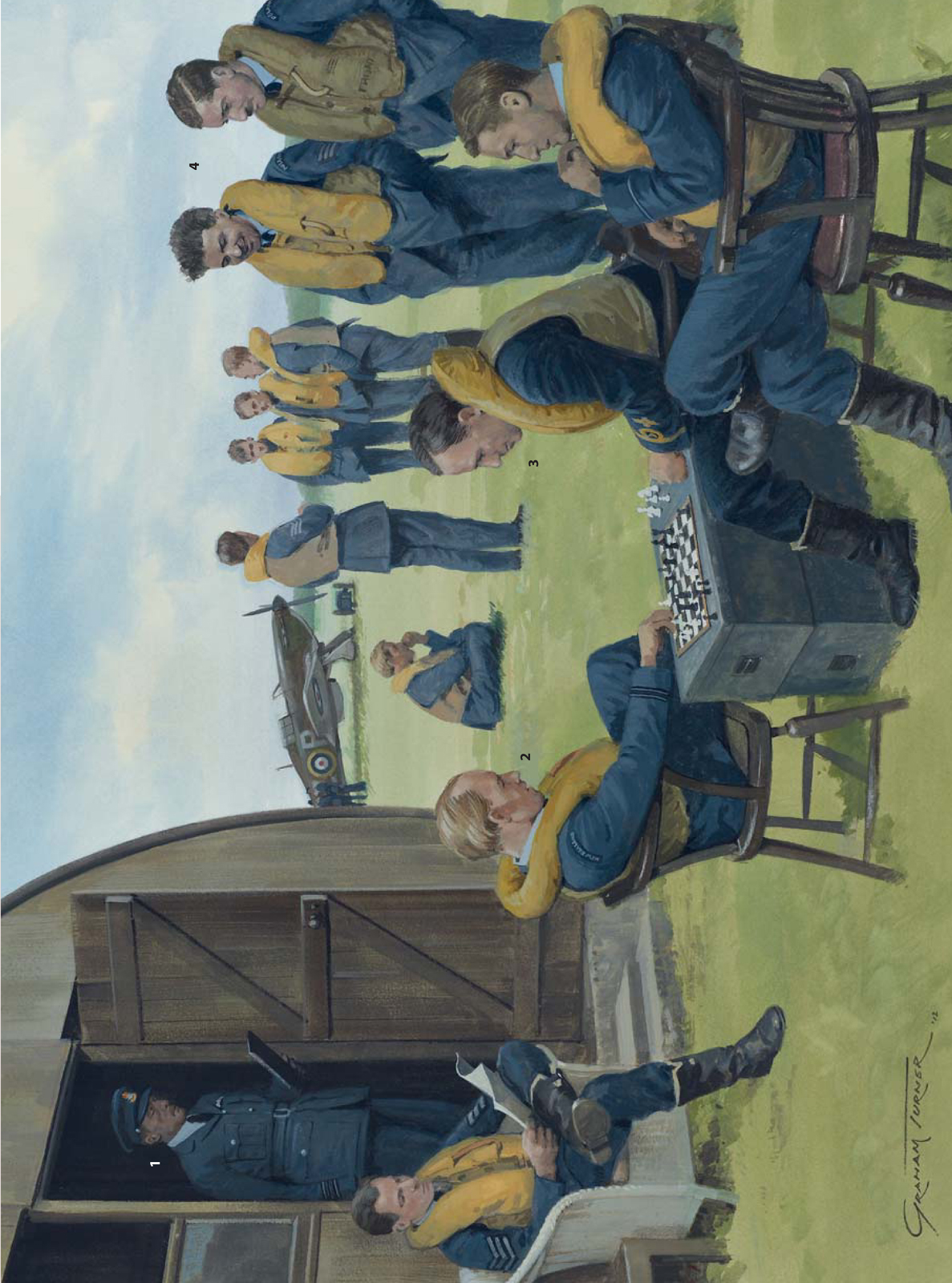

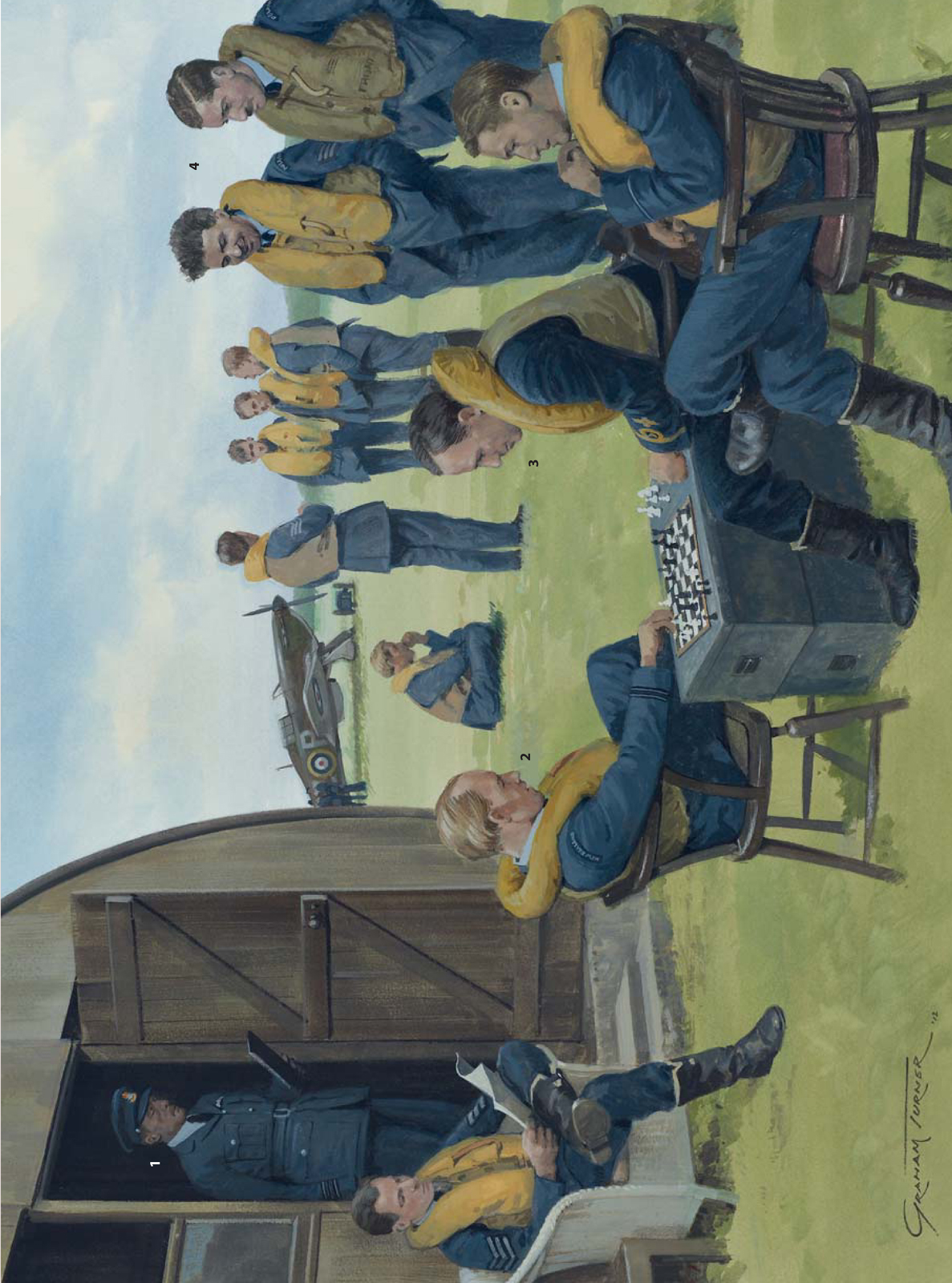

DISPERSAL, A FIGHTER SQUADRON OF NO. 11 GROUP, SEPTEMBER 1940

The ‘old hands’ are able to catch up on a little sleep between sorties or try to relax over a game of chess, while the newer pilots nervously smoke or sit in silence, waiting for the telephone to announce the next scramble. Most pilots wear their ‘Mae West’ life jackets but leave their helmets and parachutes by their aircraft. Running to the aircraft was extremely awkward when the parachute was worn properly. The squadron CO stands in the doorway, reviewing a report of the last intercept (1). ‘B’ Flight’s leader, a New Zealander flight lieutenant (2), plays chess with his wingman, a naval officer on attachment from the Fleet Air Arm (3). Two Polish pilots stand together (4), further evidence of the lengths taken by Fighter Command to bolster its numbers from outside its normal pools of recruitment. The table below illustrates the diversity of backgrounds employed by Fighter Command during the Battle of Britain, although the numbers still show the vast majority to be of British origin. |

| Nationalities of Pilots and aircrew |

Number taking part in the Battle |

Number Killed |

| United Kingdom, including Commonwealth who cannot be identified separately |

2,365 |

397 |

| Fleet Air Arm |

56 |

9 |

| Australian |

21 |

14 |

| New Zealander |

103 |

14 |

| Canadian |

90 |

20 |

| South African |

21 |

9 |

| Southern Rhodesian |

2 |

0 |

| Jamaican |

1 |

0 |

| Irish |

9 |

0 |

| American |

7 |

1 |

| Polish |

141 |

29 |

| Czech |

86 |

8 |

| Belgian |

29 |

6 |

| Free French |

13 |

0 |

| Palestinian |

1 |

0 |

| Total |

2,945 |

507 |

| Approximate number of wounded – all nationalities |

|

500 |

| Total casualties – all nationalities |

|

1,007 |

Price-Hughes goes on to describe his feelings towards the enemy and what motivation he has been able to find:

I have no hatred of Germany, quite the reverse: that perverse streak in my nature which causes me inevitably to react counter to popular opinion has led me to prefer Germans as an abstract mass to Englishmen. Why therefore am I fighting? The mainspring of my actions can, I think, be found in my vanity. I have an overwhelming desire to be the centre of attraction… at the end of the war I see a figure standing, upon his left breast rows of medals I see this hero returning in triumph from the war, feted by all as a reincarnation Rudolph Valentino, the cynosure of all eyes.

Whilst Price-Hughes’ viewpoint gives but one account, an opposite view is described by Flying Officer James ‘Jas’ Storrar in a letter to his mother during July 1940, written in several sittings during a busy period of operations at the beginning of the Battle of Britain.

It was the convoy and we got there too late… [the German aircraft] got one of our chaps, but worst of all they sank these ships blast them and we arrived to find them sinking and people wallowing about in the water. It makes me even more realise the utter futility of war, and Oh God it makes me so wild that I could scream when you see things like that. I’d like to shoot every German there is, alone [they’re] alright but as a nation they are cowardly bullying swine, and I hope that I have the good fortune to shoot down many more.

Storrar, understandably emotional in his response due to his own experiences and the fatigue of a busy period of operational flying does, however, give a very different viewpoint of the enemy once he meets a German aviator face to face: ‘I helped shoot down another Dornier this morning. We got the pilot into the mess he was absolutely green with fright to start with. I think he thought he was going to be publicly tortured. He was quite a young chappie quite decent really but very fed up with the war.’

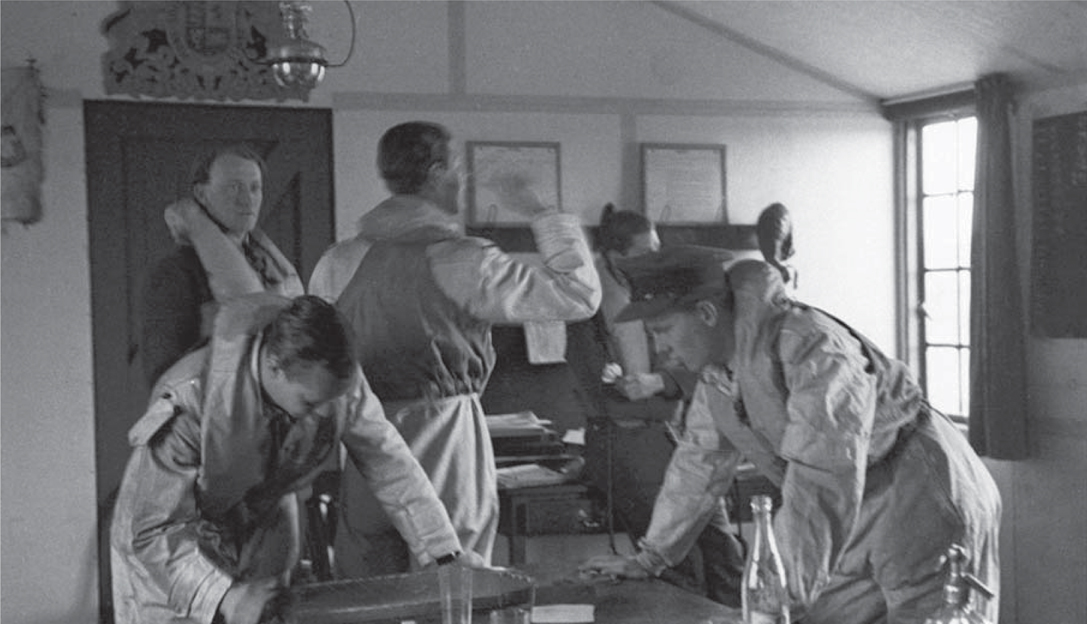

Pilots of No. 601 Squadron wait to be scrambled at RAF Tangmere. Darts, chess and other games requiring little in the way of facilities proved to be popular distractions for pilots nervously waiting for the Dispersal telephone to announce a scramble. (RAF Museum, PC98-173-171-17A)

Storarr also gives a fascinating look into the feeling of belonging within the fighter pilot fraternity within the same letter home:

I have noticed army captains look upon my dirty tunic and hat as I went into the Euston Hotel the other day with disgust and two waiters twitter about something in my dress, if they only knew how they amused me they’d think again. It is honestly amusing to meet people and be introduced as a fighter pilot, the different reactions are amazing, some think I reckon that a chappie who flies Hurricanes must be a golden-haired Adonis it rather startles them to meet nothing more than a boy, too fat to be well built too young to be able to control himself, far too dirty and untidy looking to be a figure in the public’s eye but nevertheless a fighter pilot, and typical of them all.

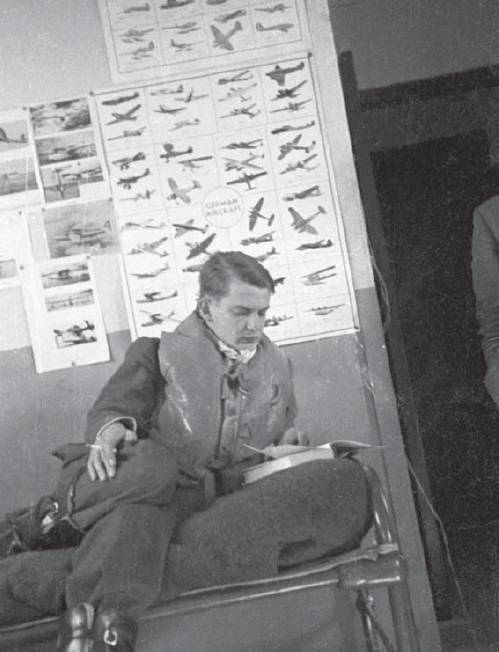

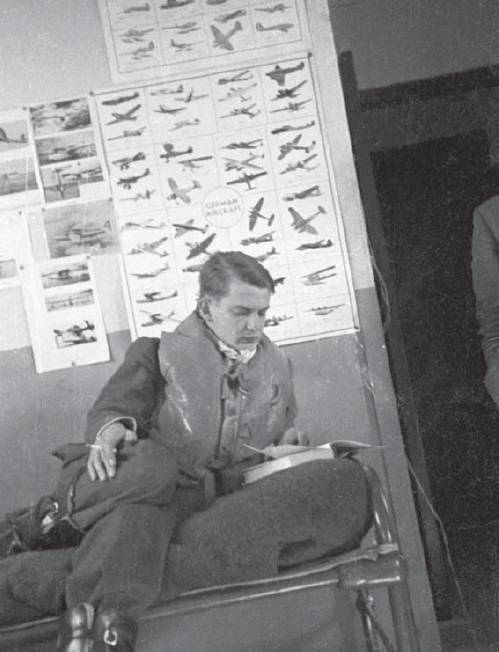

A fighter pilot reads a book in between flights. Behind him are recognition posters. In the confusion of air-to-air combat it was all too easy to mistake a friendly aircraft for that of a foe. The first fatality suffered by Fighter Command during the war was when a Spitfire of No. 74 Squadron shot down two Hurricanes of No. 56 Squadron on 6 September 1939, resulting in one fatality, and tragically, the Spitfire’s first recorded kill. (RAF Museum, PC98-173-213-1)

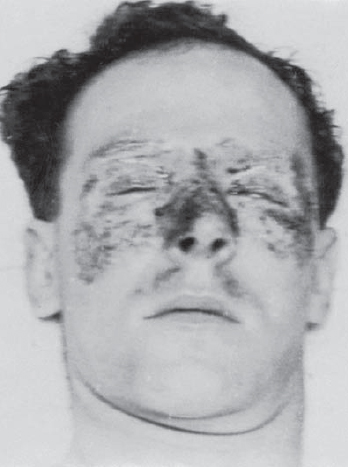

Facial burns suffered by a pilot of Fighter Command in the summer of 1940. The Hurricane was notorious for cockpit fires, resulting in the phrase ‘Standard Hurricane Burns’ being applied to the injuries of many unfortunate pilots. The renowned plastic surgeon Archibald McIndoe and his staff worked tirelessly with RAF aircrew to advance the science of plastic surgery and improve their treatment and rehabilitation. (RAF Museum, PC95-54-7)

This view ran directly against the stereotype of the fighter pilot, although this common misconception was not only a hang-up from the previous war, but also something more Germanic. The RAF entered World War II with a similar attitude to that of World War I; personal motifs on aircraft were strictly forbidden, and for Fighter Command the term ‘ace’ was not officially recognized, although it was believed by most to be any individual with five confirmed kills or more. By 1940, adding a row of kills in the form of Iron Crosses or swastikas beneath the cockpit of one’s fighter was more commonplace, but certainly not the norm. Some pilots even began to adorn their aircraft with the name of their wives or girlfriends, or even full nose art, as famously adopted by No. 242 Squadron. However, these personalized touches never became as popular as in German or American Air Forces, partly because individual aircraft frequently changed hands within a squadron as opposed to being assigned to individual pilots.

The severity of the nation’s situation was not lost on the pilots of Fighter Command, and many believed so strongly in their cause that they were willing to make the ultimate sacrifice for it, even consciously so. Flying Officer Ralph Hope was killed during the Battle of Britain – his final action was described in a letter to his family by Flight Lieutenant Archibald McKellar:

he died, quite literally giving his life for others. His plane was shot out of control over a thickly populated area and he could have baled out with every chance of success. This, though, would have meant the machine crashing where it pleased, in a factory, shop, private house or anywhere, and rather than take this risk, on behalf of the people he chose to take the risk himself, and attempted a forced landing in a large field of allotments. The plane however dived out of control before he effected the landing. Ralph was thrown clear, but it was too late for the parachute to function. It is a consolation to know that this grand action was successful: the plane did crash in the allotments and no one was injured.

Fighter Command’s aircrew not only consisted of a cross-section of British society, but also included men from nations of the British Empire. The ranks were joined by pilots from Australia, New Zealand, Canada and South Africa, eager to help stop the Nazi advance in Europe before it threatened their own homelands. Other pilots had already experienced the German advance first hand – men from Poland, Czechoslovakia and France who were fanatical in their hatred of the German foe and only too happy for the opportunities afforded to them by the RAF: a modern fighter aircraft and the chance to engage the hated enemy.