T. J. Tollakson could have been a bodybuilder, but he became a professional triathlete instead. After giving up soccer in college, Tollakson, in search of a new physical outlet, entered the popular Body-for-Life physique transformation contest. He lifted weights and ate a high-protein diet. His muscles grew so fast that he could almost see the transformation happening bit by bit. At the end of the 12-week contest, Tollakson was named a finalist. He weighed 200 pounds (at 5'10") when his “after” photos were taken.

Soon afterward Tollakson, who in addition to playing soccer had been a successful cross-country runner in high school, decided to do a triathlon. He knew he needed to lose weight to be competitive. Although his body-fat percentage was low, Tollakson understood that the excess muscle on his frame would slow him down just as much as an equal amount of excess body fat. He put himself on a 1,200-calories-a-day diet and lost 35 pounds in a matter of weeks.

A diet that supplies 1,200 calories a day is, of course, unsustainable for a competitive triathlete. After finding an ideal racing weight of 163 pounds, Tollakson went back to eating normally, always making sure he took in enough energy to support his training. But he had to be careful. While his exercise routine had changed, his genes had not. Tollakson still had a propensity to pack on muscle. The more he swam, the bigger he chest became; the more he rode his bike, the more his quadriceps inflated. Tollakson found himself sometimes gaining weight instead of losing it as he built up his training for races such as the Eagleman Ironman 70.3, which he won in 2007 and 2011, and Ironman Lake Placid, which he won in 2011.

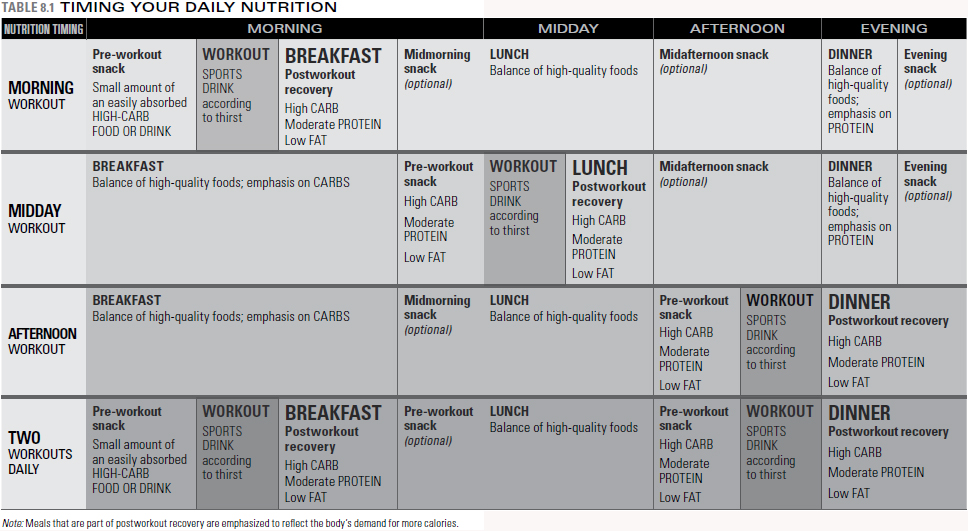

Eating less was not an option for the strapping Iowan, and his diet quality was already very high. Tollakson ultimately found success in his performance weight management efforts not by changing how much or what he ate but rather by changing when he ate. He frontloaded his daily energy intake in accordance with the dictum “Eat breakfast like a king, lunch like a prince, and dinner like a pauper.” He shifted around his macronutrients so that most of his carbohydrates were consumed before dinner and most of his protein was consumed in the evening. He became diligent in the practice of taking in recovery snacks immediately after workouts.

Tollakson often runs right after riding his bike, but he always squeezes some kind of snack into his transition between the two sessions. If he’s home, he often eats peanut butter and jelly on toast. Otherwise, he gobbles an energy bar. As soon as he’s really done training, Tollakson drinks a recovery smoothie while soaking in a cold bath. Heavy on dairy-based protein, the smoothie contains milk, Greek yogurt, whey protein powder, and frozen fruit.

Tollakson did not invent these practices. Many elite endurance athletes practice nutrient timing, as it is known, to maximize their training performance and recovery and manage their weight. It works as well for all who commit to it as it did for Tollakson. The beneficial effects of nutrient timing on body weight and body composition are also well documented in scientific literature. This is why timing nutrition is a part of the Racing Weight system.

The effects of nutrients on the body are usually ascribed to properties intrinsic to specific nutrients. Protein builds muscle, sugar causes an energy rush followed by an energy crash, and so forth. But this view is overly simplistic. The effects of nutrients on the body are actually determined as much by the context in which they are consumed as by their intrinsic properties. For example, protein is much more likely to become incorporated into muscle tissue in someone who regularly lifts weights than in someone who is inactive. In a person who lifts weights regularly, protein is much more likely to be incorporated into muscle tissue when consumed immediately after a workout than at any other time. And in a person who lifts weights regularly and has just completed a workout, protein is more likely to be incorporated into muscle tissue if it is consumed with carbohydrate than if it is consumed alone. (I’ll explain why later in this chapter.)

As our example shows, there are three major contextual factors that influence the effects of specific nutrients on our bodies: the status of the body in which they are absorbed (weightlifter versus sedentary individual), the timing of the intake (after a workout versus at any other time), and other nutrients that are ingested at the same time (protein with carbohydrate versus protein alone). In this chapter we will focus on timing.

In simple terms, nutrient timing has a significant impact on energy partitioning. You may recall from the Introduction that energy partitioning refers to the ultimate fate of the calories your body absorbs from food. There are a few primary destinations for food calories:

•Fat may be stored in ADIPOSE TISSUE, making you fatter.

•Protein, carbohydrate, and fat may be stored within MUSCLE CELLS to power muscle work.

•Carbohydrate, fat, and, to a lesser extent, protein, may be used to supply IMMEDIATE ENERGY NEEDS.

Naturally, you become leaner by shifting the balance of energy partitioning away from fat storage and toward muscle storage and immediate use. If you time your nutrient intake well, you will store less fat in your fat cells, store more protein and carbohydrate in your muscle cells, and use more calories to supply immediate energy needs than you would if you ate precisely the same nutrients but timed their intake poorly.

Effective nutrient timing is a matter of pairing your intake of calories to your body’s usage of calories throughout the day. Your body will tend to store body fat and lose muscle mass when you habitually eat more calories than your body needs to meet its energy demands for the next few hours and also—counterintuitively—when you take in fewer calories than you need to meet short-term energy requirements. On the one hand, when you take in too much, your body stores most of the excess as fat in adipose tissue. On the other hand, when you habitually consume too little at certain times of the day, your metabolism will slow so that more of the calories you consume at other times are stored as body fat, and your body will break down muscle tissue to make up for the deficit of food energy.

This negative effect of short-term food-energy deficits on body composition was shown in a study involving elite female gymnasts and distance runners, which found a strong inverse relationship between the number and size of energy deficits throughout the day (that is, periods when the body’s calorie needs exceeded the calorie supply from foods) and body-fat percentage (Deutz et al. 2000). In other words, the athletes who did the best job of matching their calorie intake with their calorie needs throughout the day were leaner than those who tended to fall behind.

Your body’s energy requirements are not consistent throughout the day. They are much greater at some times than at others. To practice nutrient timing effectively, you must maintain an eating schedule that anticipates and responds to these fluctuations in energy needs. Here are seven rules of nutrient timing that you can use to match your calorie intake with your body’s calorie needs throughout the day.

EAT EARLY. Numerous studies have shown that regular breakfast eaters tend to be leaner than regular breakfast skippers, but the reasons may surprise you. You have probably heard and read a thousand times that you should eat a good breakfast because doing so will rev up your metabolism so that you burn more calories throughout the day. In fact, however, there is very little scientific evidence for such an effect. A 2008 review published in the Journal of International Medical Research (Giovannini et al. 2008) did not include increased metabolism on a list of three possible mechanisms by which eating breakfast may promote a healthy body weight. The researchers did, however, identify three mechanisms other than metabolic increase that may explain why starting the day with breakfast is a good idea.

EAT EARLY. Numerous studies have shown that regular breakfast eaters tend to be leaner than regular breakfast skippers, but the reasons may surprise you. You have probably heard and read a thousand times that you should eat a good breakfast because doing so will rev up your metabolism so that you burn more calories throughout the day. In fact, however, there is very little scientific evidence for such an effect. A 2008 review published in the Journal of International Medical Research (Giovannini et al. 2008) did not include increased metabolism on a list of three possible mechanisms by which eating breakfast may promote a healthy body weight. The researchers did, however, identify three mechanisms other than metabolic increase that may explain why starting the day with breakfast is a good idea.

Overall reduced appetite and reduced eating throughout the day (really just two facets of a single mechanism) are both outcomes of eating breakfast. Less overall appetite is experienced throughout the day when a person eats early in the day compared to waiting longer to eat the first meal. Men and women who eat little or not at all in the morning wind up very hungry in the afternoon and evening, and as a result they overeat, more than making up for the “fasting” they did earlier in the day. A study from the University of Texas–El Paso (De Castro 2007) found that the fewer calories subjects ate early in the day, the more total calories they ate during the day as a whole.

If you plan to work out more or less immediately after waking, your preworkout nutrition should consist of a small dose of easily absorbed carbs and little else. Eight ounces of sports drink, an energy gel, or a banana will do the trick. If you have an hour or so to get ready, something more substantial—but still high in carbs and low in protein and fat—will give you an even greater lift. Consider a 12- to 16-ounce fruit smoothie, 6 to 8 ounces of low-fat yogurt, or a small bowl of oatmeal.

Improved diet quality is another potential mechanism connecting breakfast with leaner body composition. Research has shown that regular breakfast eaters typically eat more high-quality foods and fewer low-quality foods than regular breakfast skippers. This is harder to explain. More than likely, regular breakfast eaters are more conscientious eaters generally, and both their breakfast eating habit and their selection of quality foods are manifestations of their conscientiousness. In my own experience I have found that eating breakfast promotes a higher-quality diet by giving me another opportunity to work toward eating my daily quota of high-quality foods (my typical breakfast is whole-grain cereal with fresh berries and organic whole milk, orange juice, and black unsweetened coffee) and by keeping my appetite under control throughout the morning. That way, I am less likely to eat low-quality foods later, as the hungrier I am, the harder it is for me to resist the temptation of junk food.

Another benefit of eating early that is specific to endurance athletes who train in the morning is that it boosts performance and thereby enhances the training effects of the workout, including its overall fat-burning effect. When you wake up in the morning, your liver is approximately 50 percent glycogen depleted owing to having powered your nervous system as you slept. Endurance capacity is related to liver glycogen content, so your endurance capacity is reduced after the overnight fast. This is no big deal if you are doing a light workout; you won’t be limited even if you eat or drink nothing before starting it. But if your morning workout will be taxing, you will perform at a higher level by consuming some calories before starting.

EAT CARBS EARLY AND PROTEIN LATE. In their 2011 book, Hardwired for Fitness, Robert Portman, a biochemist who has developed a number of ergogenic products for endurance athletes, and John Ivy, a respected exercise physiologist at the University of Texas, argued that the macronutrient needs of athletes are not fixed throughout the day. While the overall diet should be relatively high in carbohydrate, the body’s need for carbohydrate is proportionally even greater in the early part of the day. Protein, on the other hand, is most needed late in the day. Eating in accordance with these fluctuating needs will promote favorable nutrient partitioning and a leaner body composition.

EAT CARBS EARLY AND PROTEIN LATE. In their 2011 book, Hardwired for Fitness, Robert Portman, a biochemist who has developed a number of ergogenic products for endurance athletes, and John Ivy, a respected exercise physiologist at the University of Texas, argued that the macronutrient needs of athletes are not fixed throughout the day. While the overall diet should be relatively high in carbohydrate, the body’s need for carbohydrate is proportionally even greater in the early part of the day. Protein, on the other hand, is most needed late in the day. Eating in accordance with these fluctuating needs will promote favorable nutrient partitioning and a leaner body composition.

Carbohydrate needs are elevated in the morning because, as already described, liver glycogen stores have been depleted during the night. People tend to be most active in the morning as well, and carbohydrate is the nutrient best able to supply immediate energy requirements. Athletes who work out in the morning need an early dose of carbs especially. Because the body is hormonally “primed” to convert dietary carbs to energy in the early part of the day, it does so more efficiently than it does later in the day. Carbs consumed at night are more likely to be converted to fat and stored.

Another thing to consider is that cortisol levels are high in the morning, and exercise brings them even higher. Cortisol is a “catabolic” hormone that breaks down fats, carbs, and protein for energy. Without cortisol you couldn’t swim, bike, or run very fast. But when cortisol levels get too high, a lot of muscle protein is broken down, compromising recovery. Consuming carbs before and during morning workouts lowers cortisol levels and helps recovery.

There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with eating high-protein foods for breakfast. It’s just that you can only eat so much and carbs are more important at this time. Also, the synthesis of proteins inside the body from amino acids derived from protein in food requires energy—energy that is best reserved for your daily activities and training in the first part of the day.

Many traditional breakfast foods—including cold cereal, oatmeal, bagels, and fruit smoothies—are high in carbs. These are excellent choices for your breakfasts as an endurance athlete. Dinner is another story. In the evening the body switches from energy supply mode to tissue rebuilding mode. Protein is the raw material for tissue rebuilding. Nutrient timing is all about supplying your body with what it needs when it needs it. Concentrating your protein intake in the latter part of the day will maximize muscle regeneration in the evening and through the night. Over time such favorable energy partitioning will make you leaner than if you ate more protein for breakfast and lunch and more carbs at dinner.

CONCENTRATING PROTEIN INTAKE LATER IN THE DAY WILL MAXIMIZE MUSCLE REGENERATION IN THE EVENING AND THROUGH THE NIGHT.

CONCENTRATING PROTEIN INTAKE LATER IN THE DAY WILL MAXIMIZE MUSCLE REGENERATION IN THE EVENING AND THROUGH THE NIGHT.

Again, from day to day your diet should have a consistent balance of macronutrients that favors carbohydrate, but ideally this will not be the macronutrient balance of every meal. For example, let’s suppose that your normal diet is 65 percent carbohydrate and 15 percent protein. In this case your breakfast should be closer to 80 percent carbs and 10 percent protein, your lunch 65 percent carbs and 15 percent protein, and your dinner 50 percent carbs and 25 percent protein. The exact numbers don’t matter. What’s important is that you make some effort to frontload your daily carbohydrate consumption and backload your protein intake while maintaining the right overall balance of macronutrients from day to day.

EAT ON A CONSISTENT SCHEDULE. How many times a day should you eat? Three times? Four times? More? There is no single optimal meal frequency for everyone. While three meals a day seems to be a universal minimum requirement for controlling appetite and maintaining energy levels, whether it is necessary to eat one or more snacks in addition to breakfast, lunch, and dinner is an individual matter. Even though a “grazing” approach to diet is recommended by many diet authorities, the results of research on its effects are equivocal, and in the real world many successful endurance athletes, including Olympic and World Championships bronze medalist Shalane Flanagan, seldom snack between meals.

EAT ON A CONSISTENT SCHEDULE. How many times a day should you eat? Three times? Four times? More? There is no single optimal meal frequency for everyone. While three meals a day seems to be a universal minimum requirement for controlling appetite and maintaining energy levels, whether it is necessary to eat one or more snacks in addition to breakfast, lunch, and dinner is an individual matter. Even though a “grazing” approach to diet is recommended by many diet authorities, the results of research on its effects are equivocal, and in the real world many successful endurance athletes, including Olympic and World Championships bronze medalist Shalane Flanagan, seldom snack between meals.

There is a popular belief that eating frequently increases metabolism and thereby promotes weight loss, but research does not support such a mechanism. A 2008 study by Dutch researchers compared the outcomes of normal-weight women who spent 36 hours in a metabolic chamber under two different conditions (Smeets and Westerterp-Plantenga 2008). In one session they consumed two meals per 24-hour period, and in the other they consumed three meals. Measurements taken in the two sessions revealed no differences in either resting metabolic rate or the amount of energy subjects expended through voluntary activity.

This study was limited by its short duration and the small difference in the number of meals eaten. It did not rule out the possibility that metabolic rate increases as a long-term adaptation to greater eating frequency or that those who habitually eat 6 times a day have a higher resting metabolic rate than those who eat just 2.7 times per day, as the average person does. But other studies have addressed the limitations of the Dutch study. For example, an interesting study by undergraduate researchers at the University of Wisconsin–La Crosse (Goodman-Larson, Johnson, and Shevlin 2003) compared the resting metabolic rate and eating frequency of 22 women on their habitual diets. Statistical analysis revealed no correlation between the two variables.

RESEARCH HAS SHOWN THAT EATING ON THE SAME SCHEDULE EVERY DAY IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN EATING MORE FREQUENTLY THROUGHOUT THE DAY.

RESEARCH HAS SHOWN THAT EATING ON THE SAME SCHEDULE EVERY DAY IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN EATING MORE FREQUENTLY THROUGHOUT THE DAY.

Grazing is also recommended on the grounds that it reduces appetite and total calorie intake over the course of a day. This idea appears to be a myth as well. In 2011 researchers at the University of Missouri analyzed past studies addressing the effects of meal frequency on appetite and food intake (Leidy and Campbell 2011). They found that reducing meal frequency below the standard three meals a day caused a significant increase in appetite and a tendency to overeat at the next meal. However, increasing meal frequency above the standard three meals a day had minimal effects on appetite control. In other words, increasing your meal frequency is likely to strengthen your appetite control only if you currently eat just once or twice a day.

What seems to be more important than eating a certain number of times every day is eating on the same schedule every day. In other words, once you’ve found a daily eating schedule that works for you, whether it entails three meals a day or three meals and three snacks, stick with it. Research has demonstrated a few advantages of a consistent eating schedule. A 2004 study by British scientists found that two weeks on a diet characterized by irregular meal frequency increased blood lipid levels and reduced insulin sensitivity in lean, healthy women (Farschi, Taylor, and Macdonald 2004b). A companion study involving the same subjects found that regular meal frequency increased the thermic effect of food, or the spike in metabolism that followed eating, compared to irregular meal frequency (Farschi, Taylor, and Macdonald 2004a). Together these effects indicate that an erratic eating schedule likely creates energy partitioning that favors fat storage while a consistent eating schedule creates partitioning that favors immediate energy use and muscle maintenance.

Determining your optimal eating schedule requires a little experimentation. It does not, however, require invasive measurements of insulin sensitivity and metabolic rate. You can simply go by feel. The factors to consider are appetite, energy level, and the effect of eating on your workouts. If you find that you cannot keep hunger at bay on three meals a day, you may need to snack. Nibbling between meals may also be necessary if your energy level plummets between breakfast and lunch or between lunch and dinner. If you perform poorly in late-morning workouts undertaken a few hours after breakfast or in late-afternoon workouts undertaken a few hours after lunch, snacking may correct the problem. If, however, you tend to experience gastrointestinal discomfort when you exercise too soon after eating, it may be best to avoid snacking.

While your eating schedule should be consistent from day to day, be open to adjusting your habitual meal frequency in response to changes in your training and appetite. During periods of moderate training I seldom get hungry between meals and snack once a day at most. At the height of training for marathons or triathlons, however, I’m hungry all the time and routinely eat three snacks a day in addition to three meals. What I don’t do is arbitrarily bounce around between the extremes of three and six meals from one day to the next.

EAT BEFORE EXERCISE. Eating before exercise is a nutrient timing method that will help you reach and maintain your racing weight in two ways. First, it will enhance your workout performance and thereby enhance the results you get from workouts, including that of fat burning. Second, it will directly affect your body composition by increasing the number of food calories you burn and decreasing the number of calories you store.

EAT BEFORE EXERCISE. Eating before exercise is a nutrient timing method that will help you reach and maintain your racing weight in two ways. First, it will enhance your workout performance and thereby enhance the results you get from workouts, including that of fat burning. Second, it will directly affect your body composition by increasing the number of food calories you burn and decreasing the number of calories you store.

It is not a good idea to eat a full meal immediately before working out, of course. The jostling that a full stomach undergoes during vigorous exercise may cause gastrointestinal distress. And even if it doesn’t, your workout performance is likely to be compromised by the shunting of blood flow to the gut, and away from the extremities, which normally occurs after a meal. The ideal time for a pre-exercise meal to maximize workout performance is two to four hours out. Four hours allows enough time for a large meal to clear the stomach but not so much that liver glycogen and blood sugar levels begin to drop. Two hours allows enough time for a medium-sized meal to clear the stomach.

Carbohydrate is the most important nutrient to consume in a pre-exercise meal. To maximize performance, aim to consume at least 100 grams of carbohydrate within the four hours preceding a hard workout. It does not matter whether these carbs come from high-glycemic (i.e., rapidly absorbed) food sources or low-glycemic (i.e., slowly absorbed) food sources. Studies indicate that there is no difference in their effects on subsequent exercise performance. That said, most or all of your carbs should come from high-quality foods for the simple reason that eating high-quality foods generally will help you get lean and stay lean.

WHEN THE MUSCLES BURN MORE CARBOHYDRATE DURING A WORKOUT, THEY TEND TO BURN MORE FAT AFTER THE WORKOUT.

WHEN THE MUSCLES BURN MORE CARBOHYDRATE DURING A WORKOUT, THEY TEND TO BURN MORE FAT AFTER THE WORKOUT.

Within these parameters, the precise timing and composition of the pre-exercise meal that works best are an individual matter. Most athletes naturally find a routine that suits them. To find the routine that works best for you, pay attention to how your gastrointestinal system feels and to your energy level and performance after meals of different sizes and compositions eaten at different times before exercise and heed your body’s messages.

In most circumstances the timing and composition of your preworkout meals should be optimized for performance. Nonathletes are sometimes coached to work out within an hour after eating for the sake of other benefits, including increased calorie burning (Davis et al. 1989), reduced fat storage (Aoi et al. 2012), and reduced appetite (Martins et al. 2007). While there is research to support these benefits, they are not relevant to endurance athletes. As an endurance athlete you will gain greater improvements in body composition by focusing on eating for performance.

The exception to this rule occurs within quick starts, when fat loss becomes a higher priority than performance. During quick starts I recommend weekly fat-burning workouts that are performed early in the day on an empty stomach. While you won’t perform as well in these workouts, you will burn more fat.

EAT DURING EXERCISE. It is seldom necessary or practical to eat solid food during exercise, but it is beneficial to drink and consume semisolids such as energy gels. Scores of studies have demonstrated that performance in harder workouts and races is enhanced by the consumption of water, carbohydrate, and, to a lesser extent, protein or amino acids. Consuming these nutrients regularly in your harder workouts will help you become leaner by enhancing the training effects that you derive from them, including that of fat burning.

EAT DURING EXERCISE. It is seldom necessary or practical to eat solid food during exercise, but it is beneficial to drink and consume semisolids such as energy gels. Scores of studies have demonstrated that performance in harder workouts and races is enhanced by the consumption of water, carbohydrate, and, to a lesser extent, protein or amino acids. Consuming these nutrients regularly in your harder workouts will help you become leaner by enhancing the training effects that you derive from them, including that of fat burning.

Some endurance athletes limit their consumption of calories during workouts for fear that using a sports drink or carbohydrate gel will cancel out the calorie-burning effect of training and impede their efforts to shed excess body fat. But in fact calories—specifically carbohydrates—consumed during workouts are canceled out by reduced calorie intake after workouts. A study conducted at Colorado State University found that when subjects consumed no carbohydrate during a workout, they ate 777 calories at their next meal (Melby et al. 2002). But when they took in 45 grams of carbs during a workout, they ate only 683 calories in their next meal. What’s more, the subjects consumed fewer total calories—including workout carbs—during the day in which they exercised with carbs than they did during the day when they exercised without carbs.

Consuming carbohydrate during exercise increases the muscles’ reliance on carbs as fuel and decreases their reliance on fat. Therefore less fat is burned during a workout in which a sports drink or gel product is used than in an identical workout in which the athlete drinks only water or goes thirsty. This is another reason some endurance athletes limit their use of sports drinks and carbohydrate gels in training. However, when the muscles burn more carbohydrate during a workout, they tend to burn more fat after the workout. In the Colorado State study the lesser amount of fat burning that occurred during the workout done with carbohydrate intake was almost completely compensated for by greater fat burning after the workout compared to the workout done without carb intake.

At the end of the day what matters is not what kind of calories you burned during your workout but how many calories you burned. You will tend to burn more calories in harder workouts when you consume carbs because it will elevate your performance. Like the matter of general carbohydrate intake that we discussed in Chapter 4, carb intake during workouts is another matter where you can trust that doing what’s best for your performance will also yield the best results for your body composition.

It is not necessary to take in carbohydrate in every workout. Only longer and faster workouts challenge the body enough for carb intake to make a difference in performance. As a general rule, any workout lasting longer than two hours and any high-intensity workout lasting longer than one hour will be aided by carb intake. Aim to take in at least 30 grams of carbs per hour and up to 60 grams per hour.

It is advisable to drink according to thirst and stomach comfort to minimize dehydration and its effects on performance in challenging workouts as well. A sports drink addresses both fluid and carbohydrate needs, but drinking according to thirst and comfort may not provide enough carbohydrate to maximize performance, especially during running, an activity in which tolerable drinking rates are lower. In such cases you’ll want to supplement with carbohydrate gels. You may also choose to rely on carbohydrate gels entirely to meet your carbohydrate needs. In this scenario you’ll want to hydrate with plain water or an electrolyte-fortified water.

Research has shown that there are benefits associated with consuming a small amount of protein along with carbohydrate during challenging workouts. Protein appears to delay fatigue by mechanisms that are partly independent of those by which carbohydrate works. Consequently, sports drinks and gels containing carbs and protein are more effective calorie for calorie than those that exclude protein. A study conducted at the University of Texas and published in 2010 found that a carbohydrate-protein sports drink (Accelerade Hydro) with 55 percent fewer calories per serving than Gatorade improved endurance performance as much as Gatorade (Martinez-Lagunas et al. 2010). The addition of protein to sports drinks and carbohydrate gels is also proven to reduce muscle damage during challenging workouts and thereby improve performance in a subsequent workout compared to conventional drinks and gels.

EAT AFTER EXERCISE. Eating soon after exercise is completed also promotes leanness both directly and indirectly. It promotes leanness directly by shifting energy partitioning toward muscle protein and glycogen synthesis and away from body-fat storage. It does so indirectly by accelerating muscle recovery so that an athlete can perform at a higher level in the next workout and derive a stronger training effect from it. How soon is soon? Research has identified a two-hour postexercise nutritional recovery window. What this means is that recovery proceeds significantly faster if the right nutrients are consumed less than two hours after exercise than if precisely the same nutrients are consumed more than two hours after exercise. But it is generally agreed that even within this window, the sooner you eat or drink, the better.

EAT AFTER EXERCISE. Eating soon after exercise is completed also promotes leanness both directly and indirectly. It promotes leanness directly by shifting energy partitioning toward muscle protein and glycogen synthesis and away from body-fat storage. It does so indirectly by accelerating muscle recovery so that an athlete can perform at a higher level in the next workout and derive a stronger training effect from it. How soon is soon? Research has identified a two-hour postexercise nutritional recovery window. What this means is that recovery proceeds significantly faster if the right nutrients are consumed less than two hours after exercise than if precisely the same nutrients are consumed more than two hours after exercise. But it is generally agreed that even within this window, the sooner you eat or drink, the better.

The most important nutrients to consume after exercise are carbohydrate for replenishing muscle and liver glycogen stores, protein for repairing and remodeling muscles, and water for rehydrating. For the best results, aim to consume at least 1.2 grams of carbohydrate per kilogram of body weight in the first several hours after exercise (beginning within the first hour), along with roughly 1 gram of protein per 4 grams of carbohydrate and enough water (or other fluid) so that your urine is pale yellow or clear within a few hours after the workout is completed. Again, timing is important. In a study conducted by John Berardi and colleagues, cyclists were found to have synthesized 55 percent more muscle glycogen six hours postexercise when they consumed a carbohydrate-protein supplement immediately, one hour, and two hours after exercise and then ate a small meal four hours after exercise, than when they consumed the same total number and types of calories in a larger meal consumed four hours after exercise (Berardi et al. 2006).

In this particular study, the different nutritional protocols and their disparate effects on muscle glycogen replenishment had no effect on performance in a subsequent one-hour time trial, but in other, similar studies better postexercise nutrient timing and muscle glycogen replenishment boosted subsequent exercise performance (Williams et al. 2003). Habitually consuming carbs, protein, and fluid soon after completing workouts will generally lift your performance and accelerate your fitness gains, which, again, occur primarily through the recovery process.

Proper postexercise nutrition also promotes fat burning. A meal eaten after exercise has a very different effect on the body than a meal eaten at any other time. No matter when you eat, your metabolism increases, because your body has to burn calories to digest and absorb food. But this “thermic effect of food” is greater when the food is consumed after exercise. More important, however, is the type of calories your body burns. When a meal is not preceded by exercise, carbohydrate burning increases most. But when a meal does follow exercise, fat burning increases while carbohydrate is spared so that it can be delivered to the muscles to replenish depleted glycogen stores. Thus, an athlete who routinely eats within an hour after working out will burn a little more fat and store a little more glycogen each day, and eventually she or he will wind up a little leaner than an athlete who routinely waits two hours after working out to chow down.

Not only is more fat burned, but also more muscle is built or preserved when a meal is consumed soon after exercise, as long as that meal includes both carbohydrate and protein. Several studies have shown that individuals engaged in strength training programs gain significantly more muscle when they consume carbohydrate and protein immediately after exercise instead of waiting to eat. While most endurance athletes have no interest in adding weight of any kind to their bodies, every endurance athlete benefits from maximizing his or her muscle-to-fat ratio at any given weight. Studies showing that endurance athletes build more new muscle proteins when they consume carbohydrate and protein immediately after exercise offer reason to believe that this nutrient timing practice helps endurance athletes maximize their muscle-to-fat ratio.

MINIMIZE EATING AFTER DARK. Our bodies are clocks. Recent advances in understanding circadian rhythm, or the 24-hour cycle of sleep and wakefulness and related processes, have revealed that the functioning of our bodies is affected far more extensively by circadian rhythm than was previously known. We now know that 1 out every 10 genes in human DNA operates in a 24-hour cycle. Many of these genes affect metabolism.

MINIMIZE EATING AFTER DARK. Our bodies are clocks. Recent advances in understanding circadian rhythm, or the 24-hour cycle of sleep and wakefulness and related processes, have revealed that the functioning of our bodies is affected far more extensively by circadian rhythm than was previously known. We now know that 1 out every 10 genes in human DNA operates in a 24-hour cycle. Many of these genes affect metabolism.

Our circadian hardwiring causes the same foods to be metabolized in different ways depending on when they are eaten. If first thing in the morning is the best time to eat, late at night may be the worst. Research suggests that exposure to artificial light at night disrupts natural circadian rhythms in ways that influence the timing of food intake, alter metabolism, and promote weight gain. Mice housed in a constantly lit environment eat more at night and are significantly fatter than mice housed in an environment with a natural light/dark cycle, despite eating the same total number of calories and burning the same number of calories through activity.

You’re not a mouse, of course, and it is difficult to perform this kind of controlled experiment in humans to determine whether what’s true for mice in this case it true for us. But there is reason to believe it is, because nightshift workers are known to be fatter than dayshift workers. So try to restrict your eating after sundown.

The overall body of research on the effects of nighttime eating on body weight and body composition in humans indicates that a habit of snacking in the evening does not automatically sabotage efforts to get leaner. The evidence that eating breakfast is good for weight management is much stronger than the evidence that nighttime eating is bad.

It is noteworthy, however, that many successful endurance athletes strictly limit their snacking after dark in the interest of attaining their racing weight. Triathlete Peter Reid, in addition to keeping an empty kitchen, as we saw in Chapter 5, once confessed that during the run-up to a big race he often went to bed so hungry he had a headache. I don’t think that’s quite necessary for most of us. T. J. Tollakson has said he tries to go to bed “mildly hungry.” That sounds better.

Of course, if you need a snack at night to avoid going to bed so hungry that you can’t sleep, go for it. At this time a high-protein snack is best; remember, your body is in rebuilding mode at the end of the day, and protein supports this metabolic objective. A 2012 study by Dutch researchers reported that a high-protein snack consumed at bedtime after strenuous exercise increased overnight muscle protein synthesis (Res et al. 2012). It’s all about giving your body what it needs when it needs it.