Chapter Eight

David Giammarco is a Canadian television personality and author of a coffee table book on the James Bond movies. My father became acquainted with him when Giammarco interviewed him on the failings of the CIA in the aftermath of 9/11. When Giammarco was working on his Bond book he asked my father to write a short introduction. Unfortunately, my father was too ill to write, so Giammarco wrote the intro himself and gave my father credit. This was a nice gesture, which my father deeply appreciated. In the course of their friendship Giammarco mentioned that Kevin Costner was one of his best friends. Costner, as we know, starred in the Oliver Stone film JFK, and had since become somewhat of a conspiracy enthusiast. Giammarco prodded my father about the assassination and Papa told him the same thing he’d told Oliver Stone: If the money was right, he would tell all he knew.

Later, in an incident that I was unaware of for over a year, Costner and Giammarco had flown to Miami to discuss what my father thought was a film project about his life. When they arrived at the house Laura and Austin were there, and after some small talk Costner blurted out “So, tell me Howard, did you kill the President?” They sat stunned for a moment, and my father finally said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” The meeting ended and Costner left without getting the story.

There were several things wrong with his approach. First of all he should have never asked my father anything about JFK in front of Laura and Austin. Laura would have never married my father if he’d admitted to having any involvement or knowledge of the Kennedy assassination, and I think she would have divorced him if she found out he’d been lying all those years. Without Laura to care for my father, his life probably wouldn’t have lasted as long as it did. Secondly, Costner should have been prepared to discuss a ballpark dollar amount and, thirdly, he didn’t take the time to get to know my father or for my father to get to know him. Costner came across as just another opportunist looking to make a buck. He was insensitive to the fact that the events in my father’s life, including the JFK period, had destroyed his first family and he was very protective of his second family. So, I have to wonder: was $5 million the magic number that would ease family pain?

Before I returned to California I got Giammarco’s address and phone number from my father’s Rolodex and decided to write him a letter. My reasoning was purely selfish; I had been working on a memoir and thought that Giammarco would be useful in helping me find a publisher. I wrote to him, and he called back saying that, from a marketing point of view, if my father were willing to go public with the information he felt sure about concerning JFK’s murder, it would give my book a greater chance at success.

At this point my father had only hinted to me that he had secrets. This didn’t surprise me; his whole life had revolved around secrets. To keep a secret all you have to do is keep quiet; to protect a secret you have to lie. I knew a few facts; that my father had been accused and questioned about the JFK murder; he had denied under oath any knowledge; he had lost a court case in which he was unable to satisfactorily establish that he hadn’t been in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963. A witness had testified that she had seen him in Dallas handing out envelopes of cash to Frank Sturgis, and, whether my father admitted it or not, he was a key figure in just about every sinister covert operation from Guatemala, the Bay of Pigs, the assassination attempts on Castro, to Watergate. I also knew that my father had made a career using disinformation, plausible deniability, and dirty tricks. He had well-known links to the Cuban underground and shared their deep hatred for Kennedy. How could he not have inside information on the assassination of JFK?

Something else clicked; the cryptic words my mother had said to me: “Papa was in Dallas.” I swear upon her memory that she told me this. Could there be another explanation? Maybe, but I don’t know what it is.

I told Giammarco I would give it some thought. As a word of encouragement I told him that if my father were going to trust someone it would be me. I composed a letter in which I implored him to reveal to me what he knew, if anything, about JFK’s murder. Aside from the monetary gain, I tried to appeal to him on a deeper, more personal, level. After devoting his life to the service of his government, he had been abandoned by those he trusted and served under. He had been imprisoned and stripped of his dignity. His name had been dragged through the mud by the media in connection with all manner of terrible things. His principles and his patriotism had been challenged. He lost his wife, and his family had been damaged beyond repair. Authors had profited by using his name to sell their conspiracy stories. He had never been appreciated for his own writing talents. Even though he was published some eighty times, the stain of Watergate and the media portrayal of him as a bungling burglar and second-rate writer had forever marked his career. Now, in his last years of life, shouldn’t he marshal his strength and get back at everyone by finally telling the truth? Didn’t he owe it to himself, the Nation, and his family to leave a legacy of truth instead of doubt?

I sent the letter off and waited for a reply. A few days passed and then Laura called me. “Saint, your father wants to talk to you.” I could hear Laura hand him the phone and then he said “Saint, in regards to your letter … this is something that I’m not averse to, however you need to understand that my time and cooperation is directly proportional to the financial prospects.”

“I understand that, Papa. Papa … are you there?” The phone went dead and I hung up. Conversations with my father were often one-sided; he was so deaf toward the end he couldn’t hear me on the phone and when I talked to him in person, I had to shout. He would often nod in agreement even if he couldn’t really hear you. I called Giammarco and spoke with both him and Costner about my father’s willingness to talk to me. My plan was to fly down to Miami and evaluate what information my father knew and report back to them. I wasn’t sure at this point what he knew. Flying was not something I was fond of and even less so when I realized that my flight was on Dec. 7, 2003, one day short of 31 years since my mother’s plane crashed. Laura picked me up at the airport.

“Your father’s been in the hospital for a few days … high fever and loss of appetite, but he’s home now and I know he’ll be very glad to see you, Saint.” I dropped her off at her school, drove to the house and let myself in. Austin and Hollis were both out of the country, so I knew I’d have some one-on-one time with my father. I didn’t discuss the reason for my visit with Laura because I knew she would be against dredging up all the bad old stuff. I wondered how my father would be able to cooperate with this project while keeping it a secret from Laura, but I decided to leave that up to him.

Pushing open the bedroom door, I walked quietly over to my sleeping father. He looked frail and gaunt, but as I placed my hand on his, he woke up. “Papa, its Saint.”

“Saint, so good to see you. Is Laura here?”

“I dropped her off at school. We’re here alone.”

“Good, let’s go into the kitchen. I’d like to have some soup. Are you hungry?”

“I’ll have some soup with you.” I transferred him into his wheel chair and pushed him into the TV room, where he liked to watch Fox News with the volume up full blast. I prepared some soup and we sat watching TV and discussing current events. “Papa, can we talk about my letter?”

“Okay, why don’t you take me back to my bed in case Laura comes home early? We don’t want her getting upset by this.”

“How are you going to work this out; I mean with Laura?”

“Well for the moment, she’s willing to let us talk as long as she doesn’t hear anything unpleasant. She believes what I told her: that I don’t know anything about JFK’s murder.”

“I think Laura’s very naïve about the darker side of politics.” I added.

“Well, that’s one of the reasons I love her so much.” he said. “Now let’s understand that what I tell you must be kept in secrecy and you’ll never reveal any of this without my approval. Understood?” I nodded in agreement and wheeled him back to his bedroom. I made him comfortable, and this is what he told me.

In 1963 my father and Frank Sturgis met with David Morales, a contract killer for the CIA, at a safe house in Miami. Morales explained that he had been picked by Bill Harvey, a rogue and unstable CIA agent with a long history of black ops, for a secret “off the board” assignment. It was Morales’ understanding that this project was coming down through a chain of command starting with vice-President Lyndon Johnson. Intrigued, my father listened on.

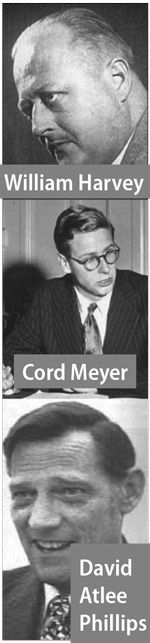

Harvey had told Morales that he’d been brought in by Cord Myer, a CIA agent with international connections, who in turn was working with David Phillips and Antonio Veciana. Phillips was CIA station chief in Mexico City and deeply involved in the dangerous world of the Cuban underground. Veciana was the Cuban founder of the violent Alpha 66 group, bent on overthrowing Castro by any means necessary. All these men shared common ground: a hatred for Kennedy. He was dangerous to their vision of America’s political future, and had abandoned them in their time of need by refusing to bail out the Bay of Pigs fiasco.

Cord Myer had his own reason to hate John Kennedy. His ex-wife Mary was one of Kennedy’s numerous mistresses, and the gossip surrounding them infuriated Cord. After the assassination, Mary Myer was mysteriously murdered and her personal diary stolen from her apartment, allegedly by James Angleton, chief spook of counterintelligence. The rumor was that Mary Myer had kept detailed notes about Kennedy and perhaps had information about his death.

Of the men mentioned thus far, my father knew Cord Myer, David Phillips, Frank Sturgis and Bill Harvey. He’d never met nor heard of Morales until that night and claimed he’d never heard of Antonio Veciana. This seems unlikely. Alpha 66 was the leading anti-Castro faction in the Cuban underground. David Atlee Phillips worked with my father closely and was actually recruited into the CIA by him when Phillips was working as a journalist in Santiago, Chile. When Lee Harvey Oswald allegedly visited the Russian Consulate in Mexico City in the summer of ’63, Phillips was station chief there. Although Phillips denied ever meeting Oswald, Antonio Veciana gave evidence that he had met with Oswald and his case officer, a man known to him only as Maurice Bishop, in Mexico City. Although unwilling to identify Phillips as Bishop, Veciana did provide a detailed description of Bishop to a sketch artist and the resulting drawing looked very much like Phillips. I sat by my father’s bedside and asked, “What happened then?”

“Well, I asked them what this assignment was.”

Sturgis looked at Morales and then at my father and calmly said, “Killing that son of a bitch Kennedy.” My father said he was stunned, but I don’t think he would have been that surprised; getting rid of Kennedy was a common topic of conversation among the Cuban exiles. The truth of the matter is that Kennedy was also hated by much of the military-industrial complex. He was viewed as soft on Communism, and many factions of the government, the exiles, the Mafia, and millions of racists were looking to get Kennedy out. My father then simply asked, “You guys seem to have enough people, what is it you need me for?”

“Well,” Frank said, “you’re somebody we all look up to … we know how you feel about the man. Are you with us?” My father looked around the room for a minute and said, “Look, if Bill Harvey has anything to do with this, you can count me out. The man is an alcoholic and a psycho.”

“You’re right,” laughed Frank, “but that SOB has the balls to do it.” The meeting ended, and my father thought it nothing more than the usual “Death to Kennedy” ranting.

The next day when my father and I were alone in the house, we discussed ways that we could divulge certain information to Giammarco and Costner without giving anything away. My father came up with a good solution: put it in code. With that plan in mind, my father provided me with a hand-written diagram outlining the chain of command, a list of people who were involved, and a descriptive time line of the events that led to the “Big Event.” This was the code for JFK’s murder. The Greek alphabet provided the code for most names, such as “Nu” for LBJ, “Beta” for Cord Myer and so forth. He also wrote a few pages of background material on Sturgis, Phillips, and Cord Myer. The reason for this was that he wanted me to type out a descriptive outline in code form and fax it to Giammarco. Hopefully it would be enough to initiate a formal agreement and a good faith payment. My father wanted $150,000 to be deposited in an account. In view of the fact that Costner and Giammarco had been dangling a multi-million dollar figure for a documentary, a book, and DVD sales and rentals, I didn’t think that $150,000 was too much. I had to wait until Laura was out of the house to type it up and fax it off.

Before I returned to California I had one more conversation about JFK with my father. He related to me that it was his understanding that Oswald had in fact fired on the President that day, but there was also another man, a French assassin, firing from the famous grassy knoll. The man’s name sounded something like Sarte or Satre, and he may have been recruited for the job by Cord Myer, who had connections to the Corsican underworld. In his own diagram, my father outlined “French con. Man … grassy knoll.”