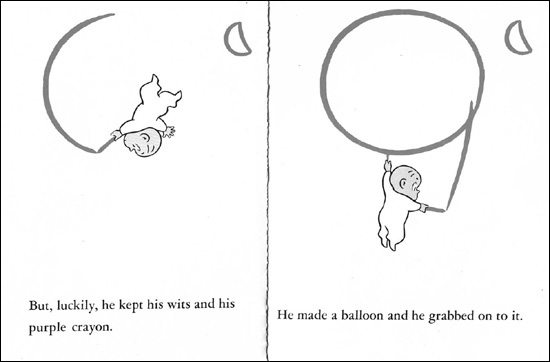

But, luckily, he kept his wits and his purple crayon.

—CROCKETT JOHNSON, Harold and the Purple Crayon (1955)

In November 1954, Dave finished dummies for Harold and the Purple Crayon. The previous year, his sister, Else Leisk Frank, and her husband, Leonard Frank, had adopted a boy, whom they named Harold David, after Harold Gold, the attorney who helped with the adoption, and her father. Though Dave was not especially close to his sister, their mother’s death eleven months earlier had brought them together, and he named his character after his nephew. The week before Thanksgiving, he sent the manuscript to Ursula Nordstrom.1

Had she known that the FBI was investigating Johnson, Nordstrom would not have cared. After learning that Howard Selsam, the husband of Harper author Millicent Selsam, was being called before McCarthy’s committee, Nordstrom replied, “I don’t care, as long as he’s not a Republican.”2

Though politically sympathetic to Johnson, Nordstrom was not initially enthusiastic about Harold and the Purple Crayon: “It doesn’t seem to be a good children’s book to me but I’m often wrong—and this post–Children’s Book Week Monday finds me dead in the head. I’d probably pass up Tom Sawyer today.” She offered to reread the manuscript when she was “more caught up” and passed it along to reader Ann Powers, whom she described as “young … and less tired than I am.” Powers was confused: “I don’t think it is anything sensational, but it is a little different” and “even bears rereadings.” She liked “falling into the sea, the sailboat” but also doubted “came up thinking fast (pun?)” and the “1st picture drawing a sail.” She thought children would enjoy “the buildings” but also wondered “why he should look for his room in both a small house and a large apt. building.” By the end of her report, she conceded, “the more I look at the book, the more I like it,” concluding, “This is undoubtedly one of those books which are indescribable in copy.”3

Three weeks later, after making a few minor changes in accordance with suggestions from Nordstrom, Johnson returned the revised Harold to Harper. Nordstrom apologized for her “lukewarm and unenthusiastic” initial reaction: “I really think it is going to make a darling book, and I certainly was wrong at first.” Her recent successes had made her overconfident in first impressions: “The Harper children’s books have had such a good fall, on so many lists, etc. etc., and I was feeling a little good—not satisfied, you understand, but I thought gosh I’m really catching on to things, I bet, and pretty soon it ought to get easier. And then I stubbed my toe on Harold and his damned purple crayon.”4

Page from FBI file of David Johnson Leisk, 20 December 1954.

On 20 December 1954, Harper sent Johnson a $750 advance and a contract for Harold and the Purple Crayon. The same day, the FBI’s New Haven office asked J. Edgar Hoover for “Bureau authority” to interview Johnson. The New Haven agents cited their uncertainty about whether Johnson “has defected from his participation in Communist front groups or from the Communist Party.” Their “informants [are] negative re current CP activity,” but the G-men wanted to be sure. They hoped that he would become an informant, which meant that the communists would have to believe that he remained loyal to them. So the FBI had to tread carefully.5

On 4 January 1955, Hoover authorized an interview with Johnson but cautioned, “Due to his employment and the extent of his activity in [Communist] front groups he should be interviewed only within the restrictions laid down by the Security Informant Program.” In January and February, the FBI’s New Haven office again had Johnson under surveillance; agents discovered that he worked mostly at home, leaving only to go to the post office, “at which time it was not appropriate to contact him.” When asked if agents might interview Johnson at home, Hoover said no: “Due to his former high position in Communist circles and due to his occupation as a writer it is not believed advisable to accede to your request. Subject should only be interviewed away from his home by experienced agents and the utmost discretion should be used in the conduct of the interview.”6

On 5 April, a federal agent visited the Rowayton house of Kay Boyle and Joseph Franckenstein and attempted to confiscate her passport on the grounds that she was then a Communist. Boyle refused and told the agent to see her lawyer. Agents had even less success with Johnson: On 22 April, the New Haven FBI office reported that attempts to interview him “have not been successful. It has required that agents stay outside of subject’s home in order to contact him. It has been noted that on the days attempts have been made to interview him, he confined himself to his home entirely. He has been observed working at a desk in his home.” In other words, they could see Johnson, he could see them, and he would not come out.7

In May, Hoover suggested that interviewing Johnson might not be worthwhile “in the light of the difficulties involved.” Fearing adverse publicity, the FBI gave up: “It is possible that if the interview were conducted under any type of adverse circumstances that it may become embarrassing to the Bureau at a later date, therefore this case is being placed in a Closed Status in the New Haven Division.” Case closed, four months before Harold’s debut.8

Though disappointed by the mixed response to How to Make an Earthquake, Krauss was looking forward to the fall publication of Charlotte and the White Horse and working on her next book. For three years, she had been collecting paintings by Rowayton schoolchildren for a visual version of A Hole Is to Dig. Where A Hole used children’s words, this new book would use their art.9

As summer approached, Ruth spent less time visiting children in the Rowayton and Norwalk schools and instead swam or sailed with Dave. Children, however, kept coming to her. As a May 1955 newspaper profile noted, “The neighborhood small fry are in and out of [Johnson and Krauss’s] comfortable house. The Johnsons are known as likely customers for Girl Scout cookies and always have a cookie available for young visitors.” Krauss explained, “I like to listen to children talking. Certain things come out that I could not catch any other way.”10

While Krauss’s busy mind gathered new material, yet another adaptation of Barnaby was in the works—this time, a weekly television show. Johnson was also contemplating other ideas for children’s books. That February, he began to consider a book about children’s imaginary friends, such as those outlined in his mock-scholarly essay “Fantastic Companions,” which appeared in the June 1955 issue of Harper’s. Though Mr. O’Malley was “a purely fictional creation,” parents had written to him about “the astonishing creatures that visited their homes.” Johnson introduced readers to six different companions, among them Bivvy, who “knocks things over and breaks things,” immediately fleeing the scene of the accident, leaving only young Mildred “by herself amidst the debris,” and Henry M.’s friend the Gumgaw, “who ‘is big, with a face like an elephant’ and who ‘talks all the time’ in a voice that surprisingly, considering his bulk, is pitched high enough to be mistaken through a closed door for Henry’s own.” Johnson asked Nordstrom about making the concept into a book, but the imminent publication of Harold and the Purple Crayon drove the idea from their minds. The book also eclipsed Johnson’s receipt of a patent for his four-way adjustable mattress, though he was optimistic about the invention’s success and told the New York Times, “I’d love to go into a motel and be asked how I’d like my bed.”11

Published in the fall of 1955, Harold and the Purple Crayon was a runaway hit. The first print run of ten thousand sold so quickly that Harper ordered a new print run of seventy-five hundred by November. The book encourages reflection on the relationship between representation and reality. Like the New Yorker cartoons of Saul Steinberg, Johnson’s drawings are metapictures, with meanings that shift as they develop. What seems to be a curve becomes a balloon, as a line of Us morphs into an ocean, and all drawings become as real as the artist character creating them.12

Harold and the Purple Crayon is also about Crockett Johnson. Where Ruth Krauss based her characters on children she observed, her husband created his child characters from his own experiences. As a child, Dave loved to draw, just as Harold does. Like Harold, Dave was a bald artist who worked mostly at night. (Of his tendency to draw bald characters, Dave said, “I draw people without hair because it’s so much easier! Besides, to me, people with hair look funny.”) Though the crayon is purple, the cover of the book is brown, Johnson’s favorite color. He lived in a brown house, furnished with comfortable brown leather chairs, and drove a brown 1948 Austin Tudor sedan. He wore chocolate-colored pants and T-shirts, often ordered from the Sears catalog. When the weather was cooler, he wore brown cardigan sweaters. If he needed to be more formal, he wore one of his brown suits. In the morning, there was no question about how to dress: brown goes with brown. The clean, unadorned style of his art, identical to Harold’s artistic style, echoes Johnson’s sartorial minimalism. That Harold should greet the viewer from a brown cover is apt because both Harold and his purple crayon are imaginative extensions of Johnson.13

Nordstrom immediately began encouraging Johnson to write a sequel: “I know you don’t want to do Harold and His Green Crayon or Harold and His Orange Crayon, but I honestly think further adventures of Harold would sell and not be a cheap idea, either.” Johnson had begun a new comic strip about a dog, Barkis, in May 1955, but it had not caught on. Brad Anderson’s Marmaduke had made its debut the summer before and cornered the market for single-panel dog-related strips, so the syndicate dropped Barkis in early November. In response to Nordstrom’s suggestion, therefore, Johnson was free to get right to work on Harold’s Fairy Tale, finishing a dummy by mid-December. From that point onward, writing and illustrating children’s books became Johnson’s primary occupation: Over the next ten years, he would create five more Harold books and a dozen others.14

Crockett Johnson, Barkis, 1955. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

It is tempting to read Harold and the Purple Crayon and its sequels as radical political commentary. The books suggest that the real world can be transformed by the imagination and encourage impulses to explore alternatives to that world, bringing to mind 1960s French student radicals’ slogan, “All power to the imagination.” The imagination, however, is neither radical nor conservative. It is amoral. By allowing us to step outside of morality, the imagination can show us that what does exist is not necessarily what ought to exist or what might exist. Echoing Percy Bysshe Shelley’s notion of the imagination as “the greatest instrument of moral good,” Harold uses his imagination with a sense of moral responsibility. In A Picture for Harold’s Room, Harold needs “rocks to step on” to climb “out of the sea and on to the hill.” Realizing that the ship he drew “was too near the rocks,” Harold “put up a lighthouse to warn the sailors.” When, in Harold and the Purple Crayon, the boy creates more pie than he can eat, he leaves “a very hungry moose and a deserving porcupine to finish” the leftovers. Harold uses his imagination to create new worlds but does so without causing harm. If the purple crayon is radical, it proposes a velvet revolution, not a violent one.15

Crockett Johnson, Harold “kept his wits and his purple crayon,” from Harold and the Purple Crayon (New York: Harper, 1955). Text copyright © 1955 by Crockett Johnson. Copyright © renewed 1983 by Ruth Krauss. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Reviewers did not see the book as radical but noted its emphasis on the imagination. Considering Harold “an ingenious and original little picture story,” the Horn Book’s Virginia Haviland wrote, “This is a little book that will be loved, for Crockett Johnson’s wide-eyed little boy and his simple lines in purple crayon are the kind of illustration to stimulate the imagination. They will suggest similar drawing adventures.” The New York Times’s Ellen Lewis Buell thought the book would “probably start youngsters off on odysseys of their own.”16

It did. Future poet laureate Rita Dove, who was three years old at the time of the book’s publication, has cited Harold as her first favorite book because “it showed me the possibilities of traveling along the line of one’s imagination,” an idea that made “a powerful impression” on her. It was the most memorable childhood book for Chris Van Allsburg, author of The Polar Express (1985) and six when Harold was published, because of both its “theme, which has to do with the power of imagination, the ability to create things with your imagination,” and its succinct presentation of “a fairly elusive idea.”17

When Harold draws a mountain to help him see his bedroom window, he climbs to the top and slips: “And there wasn’t any other side of the mountain. He was falling, in thin air.” As always, his skill at responding to an ever-changing situation saves him: “But, luckily, he kept his wits and his purple crayon. He made a balloon and he grabbed on to it. And he made a basket under the balloon big enough to stand in.” And off he goes again. Just as Harold adapts to shifting power dynamics, so did Crockett Johnson. Out of work and under surveillance, he kept his wits and began to imagine—new comic strips, a better mattress, children’s books. The purple crayon is an imaginative extension of Johnson, who had by then distanced himself from the Communist Party and had worked on Democrat Adlai Stevenson’s 1952 presidential campaign. No matter what the FBI might have thought, Harold’s crayon is definitely purple, not red. In December 1955, Johnson was asked why the crayon was purple. He replied, “Purple is the color of adventure.”18