And, if they weren’t exactly in their right order, none of them complained.

—CROCKETT JOHNSON, Harold at the North Pole (1958)

As she considered pursuing new directions, Ruth Krauss still had to earn a living. To find ideas for her children’s books, she continued to do what had worked in the past—visiting the Rowayton Kindergarten and the Community Cooperative Nursery School. Even though they knew she was older, children accepted her as one of them. If Krauss wondered what the children were discussing, she would ask. They were happy to answer and to let her take notes.1

By the first few months of 1957, Krauss had gathered enough of their stories to show Ursula Nordstrom. In April, the two women began debating which ones to include in a new book. Nordstrom liked “The Happy Egg” so much that she thought it “could make a tiny little book by itself! … 2 year olds would love it.” However, “The Mish-Mosh Family,” a story about a “whole family inside of a child,” should go. They eventually settled on seventeen tales, and Maurice Sendak began creating drawings for each. Marking a change in Sendak and Krauss’s collaborative style, the layout was uncharacteristically straightforward—the text on each left-hand page, the illustrations on each right-hand page. By late July, Sendak had finished his pictures, and he and Krauss had had settled on a title, Somebody Else’s Nut Tree, after the book’s final story, in which a child finds and adopts a pretty little nut tree, only to learn that it is not hers. That tale’s sudden shift in perspective underscores the book’s major theme—transformations.2

During the summer and fall of 1957, two major changes came to Ruth and Dave’s social circle. First, on 21 July, Simon and Schuster editor Jack Goodman died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of forty-eight. Once central to the social life of Rowayton’s artistic community, the Goodmans’ parties came to an end. Then, Phyllis Rowand remarried. Her new husband was Sidney Landau, the cofounder of Mayles Textiles, and he legally adopted Nina Rowand Wallace, joining his new family as a regular dinner guest at the Johnson-Krauss house.3

Published in the fall of 1957, Krauss and Rowand’s Monkey Day met a mixed reception. Library Journal thought it “cluttered” and “in poor taste” and marked it “Not recommended.” The New York Times Book Review’s George Woods called it “a silly, excessive story of monkey-cult devotion.” Other reviewers, however, thought Monkey Day classic Krauss. “Again it seems that Ruth Krauss has built a simple little phrase into a series of happenings that very little children will savor with delight,” wrote the New York Herald Tribune Book Review’s Margaret Libby.4

The fall of 1957 also saw the publication of Harold’s Trip to the Sky, in which Harold rides a rocket, overshoots the moon, and meets an alien “thing.” As Barbara Bader suggests, Harold’s Trip to the Sky can be read as a dramatization of the “fears of the Fifties”: “To Jung and others, the widespread sighting of UFO’s at the time stemmed from fear of nuclear destruction, and the whole of Harold’s Trip to the Sky can be seen as an expression of [these] anxieties, absorbed and transformed.” Contemporary reviewers, however, noted no political subtext and praised Harold’s Trip to the Sky as “just as funny and unexpected as ever,” in the words of the New York Times’s Ellen Lewis Buell. Booklist alleged that “some of the concepts may be too advanced for the youngest of Harold’s usual audience” but ultimately praised Harold’s Trip to the Sky as “good fun for kindergarten-age space travelers.”5

October 1957 also saw Harold take a journey to the big screen in David Piel’s film version of Harold and the Purple Crayon, narrated by Norman Rose. Johnson urged Harper to be prepared to capitalize on the movie’s imminent release. For the past year, he had been concerned that the publisher was not keeping the Harold books in stores—half a dozen people had told him that they could not find Purple Crayon—and that sales were lost as a result. The movie was due in theaters before Christmas, and he thought Harold would “get quite a bit of attention, at least enough to move a lot of books.” If Harold and the Purple Crayon “really is out of print,” he asked Harper’s Mary Russell to “please rush around the office for me, screaming.” Johnson offered to “subsidize a ‘vanity’ printing of fifty or a hundred thousand of each of [the three Harold books], to be stored in sheets ready for quick binding when a demand is indicated.”6

Harper had no intention of letting Harold and the Purple Crayon go out of print. The publisher was considering launching a line of paperback children’s books and executives thought the Harold series would sell particularly well and “could rival Pogo if we had him in paper.” Nordstrom pursued the idea, though no paperback version of Harold would be produced until Scholastic’s 1966 edition.7

When Johnson, Krauss, and assorted Harper employees went to a screening of the film in late October 1957, they loved it. By December, Piel was in negotiations with British industrialist and producer J. Arthur Rank, who expressed interest in “a series of Harold pictures, to be made with Rank money (and British government subsidy) and using less expensive British production facilities.” But the plan came to naught, and Piel had difficulty finding a distributor for his Harold. A member of the family that made Piels Beer, thirty-one-year-old David Piel was new to filmmaking: Harold and the Purple Crayon was his first. He had financed the production with a lien on the film itself, and when investors foreclosed, the animated Harold and the Purple Crayon fell into legal limbo. As with Barnaby a decade earlier, Johnson’s potential profits evaporated.8

These near misses and Johnson’s involvement in other projects may have dampened his enthusiasm for a new Barnaby book. In June 1957, a year after promising Nordstrom that he would work on it “soon,” he wrote again to say he would be in touch about it “next week.” Six months later, he had “made a start on a middle-of-the-book Barnaby sample. But I keep getting interrupted by more urgent little jobs. I still want to write it.” He never did.9

As Johnson passed on developing Barnaby’s commercial potential and bet on Harold’s, Krauss discovered that other companies were attempting to profit from A Hole Is to Dig without her permission. In 1956 and 1957, Tide, a trade magazine, sold its business services by “borrowing” phrases from the book (“arms are to hug”) and creating similar ones (“a faucet is to splash”). Extolling the benefits of advertising in Tide, one such ad announces, “A business paper is to serve.” Krauss was upset, and Harper not only asked the magazine to stop but appealed to the Joint Ethics Committee of the Art Directors Club, the Artists Guild, and the Society of Illustrators.10

A Hole Is to Dig also inspired many imitators—notably Joan Walsh Anglund’s A Friend Is Someone Who Likes You (1958), Phoebe Wilson Hoss’s Noses Are for Roses (1960), Sandol Stoddard and Jacqueline Chwast’s I Like You (1965), and Art Parsons and Leo Martin’s A Library Is to Know (1961). Parsons and Martin’s work was a tribute—an affectionate satire for librarians—but the others merely echo the Krauss-Sendak aesthetic. Advertisers embraced the child-centric definitions as adorable and sweet, and parodists mocked them out of distrust toward what they perceived as the book’s rosy view of childhood. In September 1961, Mad magazine’s “A Hole Is What You Need This Book Like in Your Head” featured cynical definitions: “A Mother is to hide behind when Daddy gets mad at you,” “Tears are to get your own way,” “A brother is to blame things on.” Though Nordstrom was not amused, Krauss had begun referring to the book as A Hole in the Head even before the Mad parody.11

A bona fide success both critically and commercially, A Hole Is to Dig embodied the best of the relationship between Nordstrom and Krauss. In early December 1957, Nordstrom showed her appreciation for Krauss and Sendak by presenting them with commemorative editions of A Hole Is to Dig, which had sold well over eighty thousand copies and was generating two-thirds of Krauss’s income. Sendak was so touched by the gesture that he promised to put it “on his table right next to the Bible and Shakespeare and Sophocles.” Nordstrom told Krauss, “We’re very glad you stepped off the Harper elevator that day so long ago with the anthropology material. And we hope you are glad too.” Krauss was: “What an absolutely wonderful surprise! I am truly touched!” Since Sendak was keeping his copy in such august company, Ruth said she would put hers on her table “right next to Jimmy Joyce and the play written by Picasso.”12

In August, Johnson turned in a new picture book, receiving the contract (with its thousand-dollar advance) in late October. The Blue Ribbon Puppies is Johnson’s most gentle book. Though it retains his characteristic ironic humor, there is no edge to it. The tone is sympathetic and the story is sweet: A little boy and a little girl decide to award a blue ribbon to the best of their seven pups but discover that each one is so adorable that they must name it the best at something.

It was the last time he did a Harper book with such complicated color separations. Problems had previously arisen with Terrible Terrifying Toby, prompting a June 1957 telegram from the author to Nordstrom: “Hold up printing of Toby at all costs colors wrong very many flagrant errors.” When he submitted detailed color art for The Blue Ribbon Puppies two months later, the work somehow was lost. Johnson had to redraw the entire book and redo the color separations, a prospect he did not relish. To achieve different colors, the offset-lithography printing process used screens to filter out a percentage of each of the inks then available—probably black, red, blue, and yellow. In this process, 40 percent blue would create light blue. To create other colors, printers combined inks by printing one layer on top of another: combining 40 percent blue with 40 percent yellow would result in a shade of green. He vowed “that my next book will be in black and white, complete in one piece, and no trouble to anybody.” Though Harper’s insurance reimbursed him $480 for the lost artwork, his next book, The Frowning Prince (1959), was indeed in black and white.13

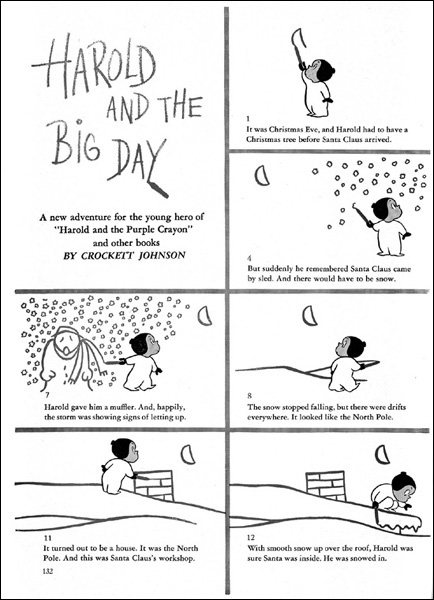

Crockett Johnson, page from “Harold and the Big Day,” Good Housekeeping, December 1957. The story read left to right across two pages. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Ruth Krauss in the living room at 74 Rowayton Avenue, 1959. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Reproduced courtesy of the New Haven Register.

Harold of course continued to draw in purple. By September 1957, Johnson had written a fourth Harold story, “Harold and the Big Day,” which would appear in the Christmas issue of Good Housekeeping. Harper then published a longer version, Harold at the North Pole in 1958. Since Johnson saved no drafts of the Harold books, comparing the thirty-page “Harold and the Big Day” to the forty-six-page Harold at the North Pole offers a rare glimpse into the mind of Crockett Johnson at work. The primary difference between the two tales is a fuller development of the narrative style characteristic of the Harold books: free indirect discourse, a third-person narrative closely aligned with a first-person point of view. In “Big Day,” “The snow stopped falling, but there were drifts everywhere. It looked like the North Pole.” In the book, “The snow stopped falling but it lay in big drifts everywhere. It covered everything.” Extending the scene to a second page, the narrative adds, “From the looks of things, Harold thought, he might very well be at the North Pole.” “It covered everything” both better conveys a child’s sense of size (the vastness of “everything”) and allows Harold to consider the scene before deciding where he is. Adding “From the looks of things” and “Harold thought” reminds us that we are seeing the world as Harold does. Johnson also delivers the insights and language of a more sophisticated, wry narrator—perhaps Johnson himself. “But Harold went speedily to work rounding up the reindeer” becomes “But Harold confidently went to work lining up the reindeer.” Lining up plays on the fact that the lines of Harold’s crayon literally create this line of reindeer. Juxtaposed with Santa’s “doubtful” look, confidently better conveys Harold’s resolve and optimism. These seemingly small differences illustrate Johnson’s genius at creating Harold’s universe—a place where every detail of the crayon’s trail is important and where the imagination has the power to change the world.

In contrast, Krauss’s method of composition focused much more on the process than on the final result. Where Johnson would write out a complete story and then modify it according to the suggestions of his editors, Krauss made many drafts. Where Johnson would send either a complete book or a selection of complete stories, Krauss often sketched out her ideas in a letter, using Nordstrom’s interest (or lack of it) to determine whether to proceed. On one occasion, Krauss asked Nordstrom if she would be interested in “a sort of bastard form between a record & a book.” The song would be something that children recognized, but adults might be unable to “finish its middle” or “to begin it right” and indeed might “get it all mixed up, instead of just not being able to remember it.” However, she wondered, “Does the child want the song to be mixed up, revolutionary, or want to have it straight?” The implication of her idea, she said, would “be that kids know things adults have long forgotten.” In another instance, Krauss envisioned a conversation between a little boy and his mother in which he announces what he would like to be, and she responds: When he wants to be a “wee mousie” so he can “run over the table,” she would be a “mother-mousie.” Krauss held onto all of her ideas, whether or not Nordstrom liked them, and sometimes reworked them.14

Krauss also continued to dream of writing for adults, joining a writing group that included Kay Boyle, Doris Lund, Bet Hennefrund, Pat Brooks, Cay Skelly, and sometimes others. Boyle and Krauss were the most accomplished of the group, followed by Skelly, the author, under her maiden name, Cathleen Schurr, of a popular Little Golden Book, The Shy Little Kitten (1946). Such a group would help Krauss in three ways. First, it would compel her to write rather than wait for inspiration, as was her inclination. Second, uncertain of her own abilities, she relied on others’ judgment in determining what worked and what did not. Third, apart from a few early pulp magazine stories, she had never succeeded at writing for adults.15

Krauss’s work for children began receiving critical praise from unlikely quarters. In 1958, W. D. Snodgrass, whose Heart’s Needle would win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry in 1960, compared the record version of The Carrot Seed (which Krauss apparently adapted) to Thomas Grey’s “Elegy in a Country Churchyard” as well as to the writings of Philip Larkin, Rainer Maria Rilke, Randall Jarrell, and Robert Frost. All, Snodgrass said, exemplify the poet’s tact, able to shape meaning “by crucial words or phrases which are never spoken.” In this essay, Krauss’s children’s story appears not just as an interesting anecdote but as an expression of a core belief about aesthetic quality.16

Although reviewers and readers liked Krauss’s new books, the sales figures did not approach those generated by the phenomenal A Hole Is to Dig. The Harold series remained a strong seller for Harper, and with Johnson producing a new volume each year, the potential income was substantial. Nordstrom made sure to let both authors know that Harper was doing its best to keep their works on the bookstore shelves. In December 1957, the F. A. O. Schwarz toy catalog featured Terrible Terrifying Toby, which could lead to big sales and was, Nordstrom explained, quite “an honor.” Both Johnson and Krauss were also “well represented” in Harper’s catalog, and the publisher was running ads for their books in the New Yorker and the New York Times. Nevertheless, fissures would soon develop in the author-editor relationship.17