And me I am writing a poem

for you

look! No hands—

—RUTH KRAUSS, “Drunk Boat,” There’s a Little Ambiguity over There among the Bluebells (1968)

In that same January 1959 letter, Ruth Krauss announced, “I have become a Poetry Nut. I’m not kidding. It has become the major interest of my life—at this point.” She was reading and writing poetry for an adult audience and wondered whether Nordstrom would be interested in a book of children’s verse. It would “have every kind of poem in it from strict ballad form to dramatic poems, looser narrative forms, little couplets just coupled (honeymooners), rhyme, unrhyme, assonance, alliteration, strict meters of every kind and no meters of every kind too.” She knew that it would “never sell like a Hole in the Head, but it will probably amble along and gather its own moss.”1

To pursue her new interest, Krauss began taking Kenneth Koch’s poetry courses at Columbia University in 1959. Though he joined the faculty only that year, Koch was an up-and-coming poet of the literary avant-garde, a founder (with John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara) of what would be known as the New York School of poetry. Some of his students (and Krauss’s classmates) in the early 1960s included Ron Padgett, David Shapiro, Gerard Malanga, and Daphne Merkin. As a teacher, Koch promoted the aesthetic sensibilities he would later summarize in “The Art of Poetry” (1975): “Remember your obligation is to write, / And, in writing, to be serious without being solemn, fresh without being cold, … Let your language be delectable always, and fresh and true.” While “poetry need not be an exclusive occupation,” Koch wrote, “You should read / A great deal, and be thinking of poetry all the time. / Total absorption in poetry is one of the finest things in existence.” Krauss considered dropping out of the children’s book field so that she could immerse herself in poetry.2

Krauss, who turned fifty-eight in 1959, was the oldest student in Koch’s class but also one of the most active participants, poet and filmmaker Gerard Malanga remembered. She “spoke up” in class, unafraid to “put [her] two cents in.” She was “really the best one in the class.” Although Koch and other teachers knew of Krauss’s successes in children’s books, most students did not; they were impressed by her poetry.3

Crockett Johnson remained immersed in an impressive array of projects. Though earlier attempts to adapt Barnaby for a weekly television show never got off the ground, in March 1959 Johnson found that it was “so live a TV property that I am almost constantly involved with some packaging outfit, network, or sponsor claiming to be on the verge of bringing it to the idiot’s lantern in a big way.” He suggested that Harper add a reference to Barnaby on the dust jacket of the forthcoming Ellen’s Lion, since a TV Barnaby “just might possibly happen about the time the book comes out.” The jacket was already in production, but Barnaby kept making progress toward the small screen, and Johnson worked on a new, more philosophical book for children.4

In October 1958, Nordstrom had asked if Johnson would be interested in writing a Harold story for the I Can Read series, Harper’s response to the Why Johnny Can’t Read crisis. Nordstrom had been planning this series for years, but Random House beat Harper into the field of reading instruction with Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat (1957), published four months before Harper’s first I Can Read book, Else Holmelund Minarik and Maurice Sendak’s Little Bear (1957). At the time that Nordstrom suggested that Johnson write an I Can Read book, Harper had just published Syd Hoff’s Danny and the Dinosaur and was recruiting other authors: Both Esther Averill’s The Fire Cat and Gene Zion and Margaret Bloy Graham’s Harry and the Lady Next Door would be published in 1960.5

Johnson said he would be interested. Working to keep his vocabulary at a slightly lower reading level than he had for his other Harold tales, he began work on a Harold I Can Read book. Inspired by the legend of the Fisher King, however, Johnson found himself writing not about Harold but about loss and imagination in what would be his most beautiful, poetic, and abstract story yet, Magic Beach, which he sent to Nordstrom in early April 1959.

In the story, two children, Ann and Ben, walk along a beach. Ann says, “I wouldn’t mind if we were in a story” because “interesting things happen.” Ben replies, “Stories are just words. And words are just letters. And letters are just different kinds of marks.” (As Maurice Sendak later observed, these are two “Beckett-like kids.”) When Ann is hungry, Ben spells JAM in the sand. A wave washes over the letters, receding to reveal “a silver dish” full of jam. They have a snack. Ben observes that “things like this don’t happen … except in stories.” Ann agrees: “In stories about magic kingdoms, usually.” After Ben draws the word KING and a wave washes over it, the king appears, sitting on a rock, fishing. The two children explain to the king how the beach works, and they summon a horse so he can ride to his castle. Then he gives them a seashell and orders them to “leave the kingdom.” With the tide coming in, Ben and Ann rush back up the steep sandbank to safety. Watching the kingdom disappear beneath the ocean, they wonder whether there was time for “a happy ending” or if the “tide came in too soon.” Ann concludes, “The story didn’t have any ending at all! … When we left, it just stopped!” She then revises her claim: “The king is still there, in the story…. Hoping to get to his throne.” Ben says nothing but puts his ear to the shell, listening to the sea.

When he sent the manuscript of Magic Beach to Nordstrom, Johnson acknowledged the Fisher King influence, adding, “I am happy to say that I have avoided adding to the confusion by making sociological analogies as [T. S.] Eliot did.” He continued,

I believe I have restored to the legend some of its pre-Christian purity by making the grail a mollusk shell. You will notice I have used no part of Mallory’s or de Troyes’ cloak and dagger crap. Perceval (or Parsifal) becomes in this version a couple of typical American kids and the wasteland is nothing but an ordinary old sandbar. I am just telling you all this in case you happen to publish the book and somebody writes in, say a librarian, asking what it is supposed to be about. It is a variation on a poetic theme, a lesson in physical geography, a Safety council message, and a spelling bee, all rolled into one.

Though he added an “‘I Can Spell’ gimmick” to the tale by having the children spell out words on the beach, Johnson noted that unless the series had “made considerable headway in stamping out illiteracy in the age group, this is not an ‘I Can Read’ book.” While confident of the quality of his story, he worried about the “limitations” of his artistic style and whether the spelling device might remind people too much of Harold’s Fairy Tale (1956), where he had “touched on the wasteland and a fisher king (albeit sans flyrod).”6

In her reader’s report, Susan Carr thought that Magic Beach “misses all around. It is not funny, it is not serious, and it is not a lovely combination of the two…. I truly do not see any way to rewrite this story to make it successful.” This “is no book with which to follow up Ellen’s Lion. It is almost impossible to believe they are written by the same man.” Nordstrom called Johnson later in April to break the news to him more gently. He conceded, “I know it is the kind of thing that has to hit somebody just right or it must go as a miss entirely.” He asked her to send Magic Beach back, and she did.7

In July 1959, Johnson wrote the I Can Read book about Harold, A Picture for Harold’s Room. As was typical, he was not sure whether the book worked, but Nordstrom and her editors thought it did. Ann Jorgensen wrote, “This would be an excellent Harold book. I like it even more than some of the already published ones.” The editors made a few suggestions about the ending. Through a trick of perspective, Harold finds himself “half the size of a daisy” and “smaller than a bird,” and Johnson originally had him walk home across the mountains and sea. Jorgensen wondered, “Is it enough to simply have Harold draw himself in his room?” If he did, then children would worry less about Harold’s ability to return. Johnson agreed, and instead of walking, Harold says, “This is only a picture!” He then crosses out the picture and draws the door to his room and the mirror hanging on its back. After drawing himself in the mirror, he says, “Yes…. I am my usual size.” In addition to more dynamic storytelling (moving forward is more compelling than backtracking), the new version grants Harold’s imagination the power to change his world.8

A Picture for Harold’s Room explores the boundary between art and life but does so without Magic Beach’s sadness and sense of loss. Picture’s title page alludes to René Magritte’s Human Condition 1 (1933), in which an easel depicts precisely what the viewer would see were the canvas not obscuring the view. Like Magritte’s art, A Picture for Harold’s Room challenges its audience to reconsider the relationship between experience and representations of experience. When Harold draws a picture on his wall and literally steps “up into the picture to draw the moon,” Johnson blurs the border that separates real from imaginary worlds, an idea he again invokes when Harold crosses out his picture and steps onto a blank page to begin drawing himself home. Though the framed picture Harold draws on the final page reasserts that border, it does so only within the broad canvas of his imagination. Since Harold never steps out of the drawing and goes back to a bedroom that is the exclusive creation of his crayon, Johnson leaves these boundaries ambiguous. This open-endedness is part of what makes the Harold books so powerful: After the final page, the unsolved mysteries of Harold’s universe linger.

Though he and his most famous character are artists, Johnson did not use that word to describe himself. Instead, he said, “I make diagrams.” This comment on his minimalist style reflects his doubts about his abilities as well as his ambivalence toward the idea of becoming an Artist. Though Johnson and Krauss had the wall space for paintings, they hung only one, an ersatz Mondrian, positioning it above the telephone to serve as a message board. As Gene Searchinger said, “It was kind of a mock painting to show what he thought. And he expressed contempt … for paintings on walls—you know, you didn’t do that.”9

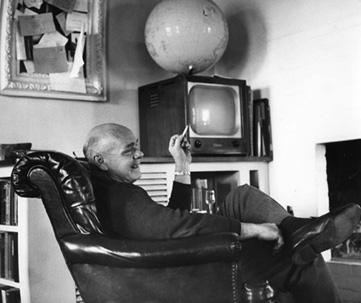

Crockett Johnson in the living room at 74 Rowayton Avenue, 1959. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Reproduced courtesy of the New Haven Register.

After Johnson reviewed the text with Nordstrom to check that the vocabulary was not too advanced, Harper put A Picture for Harold’s Room into production while Dave and Ruth put their aging dog in a kennel and took a late August vacation to New England. They drove more than three hundred miles north, spending the night atop New Hampshire’s Mount Washington, before heading to coast and taking a boat ten miles out to Monhegan Island. There, they relaxed, wrote letters, and swam together, enjoying the break from their daily routine. They had become “two of the most successful authors of children’s books in America,” in the words of the New Haven Register, which ran a profile of the couple in July. Krauss had published twenty-one children’s books in fifteen years, while Johnson had authored a dozen children’s books in seven years. They were “not really competitors,” however; as Krauss explained, “I use the children’s material and return it to them in a way they will appreciate. I call it writing from the inside out. I guess you could say I’ve learned to speak children’s language.” In contrast, Johnson described himself as working “on the principle that small children and adults are amused by the same things.” He elaborated, “Teen-agers are different, but as you get older you sort of revert to your childhood.” Krauss pointed out that her husband was “lucky he can do everything himself. He writes and draws pictures, and even lays out the pages. He can work mostly from home and hardly has to consult anyone. But I have to work with so many different people and I have to take so many trips to New York.” Poetry, however, was a solo pursuit, enabling Krauss to avoid the trials of collaboration.10

Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss in front of 74 Rowayton Avenue, 1959. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Reproduced courtesy of the New Haven Register.

Back in Rowayton, Krauss resumed work on Philosophy Book, which she had begun to call The Book from Outer Space and which would be published in 1960 as Open House for Butterflies. Sendak had drawn some illustrations, and Krauss invited him up to the house to do some more work—a few tiny figures for the corners and some double spreads to give it “more ‘fullness’ in look.” After spending a day in Connecticut, Sendak returned to New York un-enthusiastic about the project. “I felt like this was A Hole Is to Dig II,” he later said, “a non-spontaneous version” of the earlier book. As a result, his drawings of little people “had hardened. They had none of the evanescence and silliness and clumsiness of the drawings in A Hole Is to Dig.” Sendak’s feelings may have resulted in part from his perfectionism as well as from the fact that Krauss had turned her attentions more toward her poetry. As she wrote when the book came out, “I guess I like Open House for Butterflies. I’m not sure of course. Now that I’ve turned poet, I’m not sure of anything.”11

Krauss’s focus on poetry and Sendak’s independent success ended their close relationship. “I’d been launched, and once I’d been launched, not only was our collaboration ceased but even the friendship did,” he says. Sendak and Johnson would send each other signed copies of their latest books, but he felt that “that wonderful nest which lasted almost ten years was just gone. There was no discussion.” Sendak thought that Ruth and Dave had grown to dislike him, but he was wrong. They saved every card or letter he sent, newspaper articles on him or his work, and copies of essays he wrote. Though they might never have told him so, they both cared about him and were proud of him.12

Krauss began to identify herself primarily as a poet, not a writer of children’s books. She often signed her letters to Nordstrom with fanciful pseudonyms—“Ruthie Kraussie,” “Ruthless K.,” “La Krauss,” “Ruth the ‘Mad,’” “Kruth the Sauss,” and “your dear friend, Ruthie Kruthie the last of the Lausses.” In August 1959, she added “Onward Folly,” describing it as her “poetry name” and using that alias regularly over the next few years. She was fashioning a new identify for herself—Ruth Krauss, poet.13

If the humor in A Hole Is to Dig or Open House for Butterflies offered a laugh of recognition at the perspective (and perceptiveness) of children, some humor in Krauss’s poems addressed serious subjects. As David Lehman says of Frank O’Hara, “The prejudice against humor and lightheartedness in poetry has caused some readers to overlook … the incisive way his work captures a world, a time, and a place” as well as the poems’ “news and cultural commentary.” This claim captures the sensibility of Krauss’s “Poet in the News,” a brief prose poem composed in 1959:

A crowd of twenty-three thousand coy mistresses is expected to turn out this morning for the forty-four day ruby-finding meet by the Indian Ganges’ side. Eighth race on the card is scheduled for quaint honor to succumb to the tide at 4:35 P.M. and will be telecast. Thus while her willing soul transpires she who wins shall take her due except she come up with the same bruised thigh that put her out of action last week.

Couching commentary in comedy, Krauss combines the diction of the evening news with that of Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress.” Transforming the carpe diem poem into the latest news, she underscores the absurdity of both genres. She mocks the news’s insistence on quantifying everything by parodying its objective-sounding numbers. She highlights the ridiculousness of figuring love-making as a race against time. Alluding to Marvell’s violent imagery in her line “the same bruised thigh,” Krauss also pokes fun at the blunt, unromantic entreaties—“scheduled for her quaint honor to succumb at 4:35 P.M.” makes sex sound more like keeping an appointment than an expression of passion.14

“Poet in the News” was the first of Krauss’s news poems, all inspired by Koch’s and O’Hara’s “headline” method. Both men liked to sit down with the day’s New York Times and create poems from the words they found there. Most of Krauss’s headline poems are purely absurdist. One of her many prose poems called “News” reads, “‘This measure,’ the Attorney-General stated, ‘This legislation—which I endorse—requires some thirty thousand skylarks to register for the first time with my office.’ And he left the room.” One of many poems titled “Weather” reports, “Drizzle tonight off the east coast of my head.” These poems lack any definite political goal, focusing instead on startling the reader with their freshness. As Lehman says of Koch, Krauss writes “as if it were the first obligation of the poet to provide a continual sense of surprise.”15

Krauss’s “If Only,” one version of which is dedicated to Koch and George Annand, developed from an assignment Koch gave his students. He brought in André Breton’s poem “The Egret,” which begins, “If only the sun were shining tonight / If only in the depths of the Opera two breasts dazzling clear / Would ornament the word love with the most marvelous living letter” and asks such questions as “Why doesn’t it hail in the jewelry shops?” Koch used Breton’s poem “as a model for an ‘If only’ poem” because “Breton’s poem is full of wishes for the impossible.” Krauss clearly enjoyed the exercise, writing her first iteration of “If Only” in 1959 and revising and publishing different versions of it for the next decade.16

“Poet in the News” first appeared, along with three of Krauss’s other prose poems, in the December 1959 Bards’ Bugle, a mimeographed publication that was, as its masthead noted, “dedicated to the great unpublished. So far, that is.” In her first published poems as an “adult” poet, Krauss combines the spontaneous verve of a child’s words with some of the diction of “grown-up” writing. One of the poems reads, in part, “Words cannot express me. But as someone said, they really don’t have to. They are more like hands across the sea or toes under the table. What fun!” She saw herself as “becoming an avante-garde poetess.”17

In early December 1959, Johnson and Krauss flew to Hollywood to attend rehearsals for Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley, a full-color pilot episode for a new Barnaby series starring Bert Lahr as Mr. O’Malley, five-year-old Ronny Howard as Barnaby, and Mel Blanc as the voice of McSnoyd. Johnson loved meeting Lahr and thought he was great as Mr. O’Malley. Filmed at CBS, this Barnaby had one big advantage over previous dramatizations: Since it was not live, director Sherman Marks had more room to manipulate the performance, including doing multiple takes and adding music and sound effects after the fact.18

Marks’s fine-tuning paid off. Introduced by Ronald Reagan, the half-hour program aired on CBS’s General Electric Theater on 20 December and received strong reviews. The New York Times’s Jack Gould called it “a charming and hilarious holiday spree” and thought Howard “the most engaging child performer in many a day.” Variety predicted that Howard’s agent would soon find his phone ringing “with enough offers to keep [Howard] busy until next Yule time.” Variety was right: In 1960, Howard landed the role of Opie Taylor on the Andy Griffith Show.19

Back in Connecticut after Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley’s success, Ruth and Dave faced the final months of Gonsul’s life. Though their seventeen-year-old dog had been ailing for the past couple of years, he had been their companion for nearly all of their life together. He was the inspiration for both Barkis and Toby. In March 1960, as the winter’s snow last began to yield to spring, Gonsul died. However, as Dave said, “By the comparable longevity standard for mammals, figuring his puberty period at less than a year and ours at less than twenty, he lived 350 years. Quite a while.”20

Crockett Johnson, drawing of Bert Lahr as Mr. O’Malley, 1959. Image courtesy of the Estate of Ruth Krauss. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Krauss found herself wanting to focus solely on poetry but unable to leave her children’s books behind. Nordstrom suggested that Johnson or Sendak illustrate Krauss’s next one, but she wanted someone new: “You know, Dave & I really do not want to work together; after all we’ve been married some 20!! years.” She also did not “think Maury & I want to work together particularly either, although we get along that way.” Moreover, both men were busy with other projects. Sendak was illustrating three books a year as well as writing and illustrating The Sign on Rosie’s Door (1960) and the four-volume set The Nutshell Library (1962). Johnson published four books in 1959 alone.21

Early in the new decade, however, Johnson’s pace slowed dramatically. He published only one book in 1960 and no more until 1963. The rejection of Magic Beach had been discouraging, and other commercial projects demanded his attention. By early 1958, he had begun doing some work for Punch Films, run by his old friend, Lou Bunin. When Dave Hilberman organized Film Designers in 1959, he invited Johnson to join his roster of artists. A cofounder of United Productions of America and leader of the 1941 Disney animators’ strike, Hilberman had since 1946 been running the Tempo Productions commercial cartoon studio New York, where he would often meet Johnson for lunch. For Film Designers, Hilberman enlisted Johnson’s friend, Antonio Frasconi, already acclaimed as a painter and woodcut artist; Tomi Ungerer, then the author of a new picture book about Crictor, a boa constrictor; and Punch illustrator Ronald Searle, cocreator of the four Molesworth books (1953–59). Johnson was in good company.22

In March 1959, taking advantage of a chance to explore his interest in math and science, Johnson worked on a series of animated films about Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. Educational films intrigued Johnson, but films designed purely to sell products did not. In April 1959, when Bunin invited him to work on some ad campaigns, Johnson confessed, “It is my old trouble in dealing with these people. For the length of time it takes to do a job properly I find I can’t keep myself pretending that advertising men and their problems are real.” On another occasion, he sent Bunin a mock advertisement for Bosco chocolate syrup that was even more sarcastic than the parodies then running in Mad magazine.23

Under very narrow conditions, however, Krauss agreed to let her work be used for other purposes, including advertising. In April 1960, she wanted to sue Whittlesey House for publishing Phoebe Wilson Hoss’s Noses Are for Roses (1960), which paraphrased her “Toes are for wiggling” and “Arms are for hugging” as “Toes are to wiggle” and “Arms are to hug with.” However, when Merck offered to pay and give credit to A Hole Is to Dig, she and Sendak agreed to the book’s use in a campaign for a drug. With Sendak’s art and Krauss’s text, each ad used three definitions from the book, concluding with the slogan “Redisol is so kids have better appetites.” Krauss also granted dancer Margot Harley permission to adapt A Hole Is to Dig for a March 1960 Contemporary Dance Productions performance in New York.24

In late April, Krauss and Johnson walked up the street to bring some of their books to the new Rowayton Arts Center. A minute’s walk from their home in what had previously been Nelson’s Lobster House, the Arts Center recognized the town’s growing community of artists and writers. The first board of directors included Jim and Jane Flora, and among the center’s first programs were an exhibit by Jane Flora and a lecture by Kay Boyle. Krauss was amused by the location but pleased by the attention it was bringing to local artists. As she told Nordstrom, “The place is a ‘shack’ over the River (well, not quite), but the amazing number of people filing through it this weekend resembles the opening of the Guggenheim.”25

One of the books Krauss brought to the Arts Center was Open House for Butterflies, which was receiving mixed reviews for her text but praise for Sendak’s pictures. Echoing the artist’s assessment, Kirkus felt that the new book “lacks the spontaneous charm of” A Hole Is to Dig, though the reviewer praised the “irresistible diminutive drawings”; the text was “charming, funny, sometimes wise.” Not trusting his own judgment, the New York Times’s George Woods sought the opinions of children: “Not only does its point and purpose escape me, but it also baffled six children to whom it was carefully, hopefully read.” However, the children “loved Maurice Sendak’s abundant and enchanting miniatures.” The Saturday Review’s Betty Miles offered a more thoughtful assessment, noting that, to “a young child the comment that ‘grownup means to go to nursery school’ is flatly logical. To an adult it has a poignancy no child could understand.” Lamenting what she saw as Krauss’s decision to talk over children’s heads to adults, Miles hoped for “more of the children’s books that Miss Krauss used to write with such verve and insight: The Carrot Seed, The Growing Story, The Big World and the Little House were real juveniles, the kind that real children beg to have read to them in real living rooms.”26

On 5 May 1960, Dave and Ruth were having martinis and dinner in their living room with two other couples, Ken and Jackie Curtis and Jimmy and Dallas Ernst. After dinner, a news bulletin interrupted the game they were watching on TV. The Soviet Union had shot down an American U-2 plane, claiming that it was a spy plane. According to the U.S. government, the plane had been “studying meteorological conditions found at high altitude, had been missing since May 1,” when the pilot reported difficulty with his oxygen equipment while flying over Turkey, near the Russian border. Dave immediately said, “Oh, what a cock-and-bull story.” Though they were liberals, the Curtises and the Ernsts did not share his skepticism. Jackie Curtis asked, “Well, why would the U.S. government lie about such a thing?” Within a week, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev would produce the pilot, Francis Gary Powers, who had survived the crash, along with the film in the plane’s surveillance camera. Dave’s suspicions were warranted.27

As the news grew stranger, Krauss’s “surrealist-type news-items,” as she called them, were finding readers—in June 1960, the Village Voice agreed to publish a dozen. Krauss also thought that if Nordstrom would publish “If Only” in “picture-book form” but “not for children,” the result “could be pretty popular.” Nordstrom disagreed but was willing to help reissue A Good Man and His Good Wife with new illustrations. They tossed some names back and forth. Jules Feiffer had drawn up a dummy for the book some years earlier, but “he’s terribly popular” now and has “never done a children’s book.” Krauss added parenthetically, “probably never will now,” not knowing that Feiffer was then illustrating Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth (1961). She and Nordstrom also considered R. O. Blechman, author-illustrator of The Juggler of Our Lady (1952), and Marc Simont.28

The original illustrator of A Good Man, Ad Reinhardt, came up to Darien and Rowayton on 30 July to visit Jimmy and Dallas Ernst, Abe and Betty Ajay, and Johnson and Krauss. A few years had passed since they had seen Reinhardt, now a famous abstract painter. The visit reconnected the two men, and they began to correspond.29

Spending time with old friends who had become successful artists and with Abe Ajay, who was abandoning his commercial art career to become a painter and sculptor, prompted Johnson to ponder his own future path. He was creating fewer children’s books and hoped Barnaby might yet prove an on-screen hit, but he was growing creatively restless. His wife also served as a role model: She was now submitting her poems for publication in both smaller venues and larger ones. The year 1961 would be the first since the start of her career without a new Ruth Krauss children’s book.