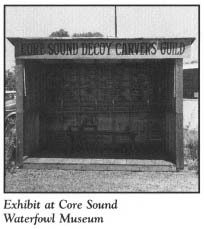

This tour begins northeast of historic Beaufort at the junction of U.S. 70 and S.R. 1300. Proceed north on S.R. 1300.

This tour begins with a drive through the area known as the “Open Ground,” visiting the villages of Merrimon and South River. Next, it examines the tiny maritime villages along Core Sound, collectively known as “Down East”: Bettie, Otway, Straits, Harkers Island, Gloucester, Marshallberg, Smyrna, Williston, Davis, Stacy, Sea Level, and Atlantic. It then visits Cedar Island before ending at the landing for the Cedar Island-Ocracoke Ferry.

Among the highlights of the tour are the largest farm in the eastern United States, the Down East villages, Harkers Island, the story of Shell Point, “the Miracle at Davis,” Sailors’ Snug Harbor, and Cedar Island National Wildlife Refuge.

Total mileage: approximately 104 miles.

This route will take you on a 15-mile odyssey to a wilderness region rarely seen by anyone other than locals. Bounded by Adams Creek on the west, the Neuse River on the north, U.S. 70 on the south, and Cedar Island on the east, the Open Ground Prairie Swamp—alternately known as “Open Ground” or “Open Land”—is a desolate 50,000-acre expanse of sand and peat bogs.

In 1926, an attempt to reclaim this vast wilderness was unsuccessful. A wealthy Philadelphian, Georgiana Yeatman, subsequently acquired huge chunks of land just west of Adams Creek, a large waterway at the northwestern corner of Carteret County, in the early 1930s. For several years, she ran an experimental dairy operation with a sizable herd of Guernseys. Later, she spent a fortune transforming a portion of the Open Ground into pastureland. Trainloads of lime were trucked in, and extensive drainage canals were dug. Ultimately, the project was abandoned.

More than forty-five thousand acres of the Open Ground were sold to an Italian conglomerate around 1970. That company invested more than $20 million to begin the largest farming operation in the history of the county. Following several years of difficulties with state and local health agencies, the agricultural enterprise began to prosper. Today, Open Grounds Farm, which produces corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, and beef cattle, is the largest farm east of the Mississippi River.

There are only two communities within the confines of the Open Ground.

Merrimon is a small farming hamlet of several hundred persons. To reach it, turn left off S.R. 1300 onto S.R. 1318 approximately 12.3 miles north of the intersection of U.S. 70 and S.R. 1300. Proceed 1.5 miles on S.R. 1318 through Merrimon. The village is located near the banks of Adams Creek, a scenic water course that serves as the route of the Intracoastal Waterway, linking the Neuse River with the Newport River via Core Creek Canal. On clear days, visitors to Merrimon can see the sailing town of Oriental just across the Neuse River.

Retrace your route to the junction with S.R. 1300 and continue 3.3 miles on S.R. 1318 to South River, the second human outpost in the open expanse. Set on the banks of the river of the same name, this small village is a fishing community. A boat ramp provides access to the 9.5-mile-long river.

From South River, retrace your route toward the junction with U.S. 70. For an interesting side trip, turn west off S.R. 1300 onto S.R. 1163 approximately 9.8 miles south of Merrimon. After 2.3 miles, S.R. 1163 intersects N.C. 101. Turn north on N.C. 101 and drive 4.2 miles to Harlowe Creek.

Prior to the completion of the Adams Creek link of the Intracoastal Waterway, the Clubfoot-Harlowe Canal, of which Harlowe Creek is a part, was the main water route from mainland Carteret to the Neuse. Known locally as the Slave Canal because it was deepened to five or six feet by slave labor in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, it is one of the oldest canals in the United States. It was created untold centuries ago by Indians who dragged their canoes across the lowlands to the Neuse. Though the canal is long and straight, it is extremely narrow and shallow, and lack of maintenance has made it perilous to navigate.

Return to the junction of S.R. 1300 and U.S. 70. Proceed east on U.S. 70.

The only bridge spanning the North River crosses the water 0.8 mile east of the junction. The wide, 10-mile-long North River empties into Back Sound, a body of water separating Harkers Island from Shackleford Banks. An imaginary line runs north from the North River across mainland Carteret County, marking the boundary between the Beaufort-Morehead City-Bogue Banks resort areas and the northeastern peninsula of the mainland. “Down East Carteret,” as this peninsula is known, is one of the last vestiges of the rural fishing and farming economy that once dominated most of coastal North Carolina.

Until World War II, the Carteret communities lying east of Beaufort existed in a state of virtual isolation. Bridges, electricity, and other modern conveniences have come to the area only in the past fifty years. Nevertheless, Down East has not sacrificed its quaint charm. The residents live in peace with the land and sea, as their ancestors did for centuries. Boats, fishing nets, and vegetable gardens are in evidence in the yards of most of the modest white frame homes. In this land of stark natural beauty, man and the coastal environment exist in harmony.

Located 0.8 mile east of the bridge over the North River, Bettie, a small hamlet of three hundred persons, is the first of the Down East communities you will encounter on U.S. 70. Known as the “Gateway to Original Down East,” it was named for the daughter of an early settler in the area.

Despite the incursion of the outside world through the automobile and television, Bettie and its sister villages remain among the last places in the nation where visitors can hear “the queen’s English”—English spoken as it was when America was first settled. To the uninitiated, this strange brogue may seem uncultured. However, words and expressions still in use by lifelong residents of Down East are found in English literature of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Twice a day, the “toide” (tide) gets “hoigh” (high) for the “Down Easters.”

Continue 2.4 miles east on U.S. 70 to the community of Otway, which is separated from Bettie by Ward Creek, a tributary of the North River. Bearing the name of Carteret County hero Otway Burns, this is one of two towns in the state named in honor of the famous privateer. Burnsville, in western North Carolina, is the other. Approximately five hundred people live in Otway.

At Otway, the tour veers away from U.S. 70, making a southern loop around a neck of land separated from Harkers Island by a strip of water known as “The Straits.” Turn right, or south, off U.S. 70 onto S.R. 1325. After 0.3 mile on S.R. 1325, turn left onto S.R. 1331 and drive 0.2 mile to S.R. 1333. Turn right on S.R. 1333 and proceed 3 miles to the village of Straits. Along the route to this small farming and fishing village, you will enjoy a panorama of beautiful farm country and semitropical woodlands. Approximately 0.5 mile north of the community, a bridge affords a spectacular view of the North River at one of the river’s widest points.

Because Straits is located just north of the bridge to Harkers Island, it has a high volume of traffic. However, the village was an isolated place until World War II, since the unpaved road from Otway was virtually impassable in bad weather and the ferry landing for the trip to Harkers Island was located 2 miles east, at Gloucester.

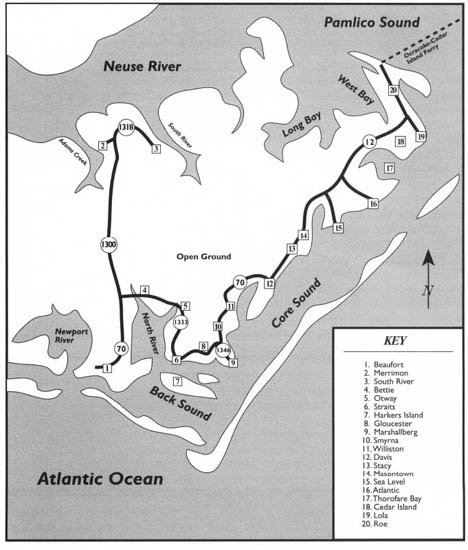

Straits is the home of the oldest Methodist church in Down East. This church was built around 1778.

In 1813, the Methodist minister in Straits played an important role in an event that was the basis of one of the most enduring Down East legends. Village residents were starving in the winter of that year. A crop-killing drought the previous summer was followed by deadly winter cold that choked the nearby sounds with ice. Fishing was impossible, and there was no food stored in the village. A wartime blockade by the British fleet prevented trade with the outside world. When almost all hope had faded, the Reverend Starr sought divine intervention. Lifting his voice to heaven, the pastor prayed, “If it is predestined that there be a wreck on the Atlantic coast, please let it be here.” Whether by coincidence or providence, a ship with a cargo of flour wrecked on nearby Core Banks a few days later, saving the community from disaster.

In the modern village, Starr Methodist Church memorializes the minister who uttered the famous prayer.

In Straits, turn south off S.R. 1333 onto S.R. 1335 for the 1.8-mile drive to Harkers Island. The Straits Fishing Pier, located along this route, is a public facility maintained by the Carteret County Parks and Recreation Department. It affords a beautiful vista of the surrounding waterways.

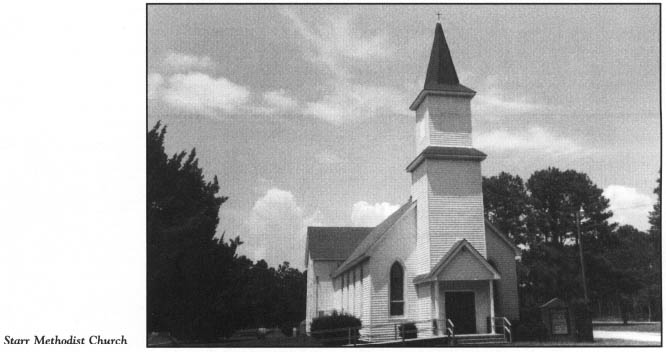

Many visitors get their first real taste of the salty flavor of Down East Carteret at Harkers Island. Situated almost due east of Beaufort near the mouth of the North River, the 5-mile-long, 1-mile-wide island is bounded on the north by The Straits, on the south by Back Sound, and on the east by Core Sound. Its location on the sounds offers protection from the fury of the wind and sea, which often plagues the nearby barrier islands.

The bridge across The Straits delivers vehicles to the western end of Harkers Island. On the island, S.R. 1335 becomes Harkers Island Road. Proceed east as the road winds its way for 5 miles to the eastern end of the island on Core Sound.

More than three thousand people currently live here, making Harkers Island the most populous of the Down East communities. Over half the population is clustered in the village on the southern shore. Hundreds of other homes and cottages are located along the winding, shady island road.

Its Down East charm and its proximity to the Carteret County beaches have made Harkers Island increasingly attractive to vacationers. At the height of the summer season, the population doubles. Motels and restaurants have been built over the past thirty years to accommodate the growing number of tourists.

On the drive down the island, you will note that the yards of many homes disclose evidence of one of the oldest industries of the island: boat building. Wooden boats of all sizes and in various stages of construction can be seen throughout the year all over the island. This “backyard boat building” has evolved into an important industry that includes a half-dozen boatyards.

Early boatbuilders on the island worked without blueprints. They developed the distinctive Harkers Island flared bow, now the trademark of island craftsmen. Despite a nationwide decline in sales of wooden boats, boat buyers all along the eastern seaboard are attracted to Harkers Island boats because of their excellent construction and dependability.

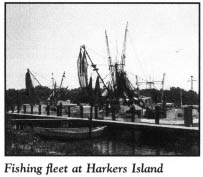

Located approximately 3.1 miles from the bridge, the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum is dedicated to the preservation of traditional decoy carving and the history of waterfowl hunting in Down East. Operated by the Core Sound Decoy Carvers Guild, the facility is housed in temporary quarters until a $1.5-million complex containing a museum and gallery can be completed. During the first weekend in December, the guild sponsors the Core Sound Decoy Festival, during which dealers, collectors, and carvers showcase decoys, artwork, and publications.

From the museum, drive east to the end of the island. The recently completed Cape Lookout National Seashore Headquarters/Visitor Center overlooks Core Sound at the end of the road. Park in the parking lot and take a few minutes to enjoy the exhibits and programs at the facility.

Walk across the road to the scenic park overlooking Back Sound. Picnic tables are spread about the grassy area at the water’s edge. From the park, you can catch a glimpse of the Cape Lookout Lighthouse on Core Banks, just across Back Sound.

Since the completion of the Cape Lookout National Seashore Headquarters/Visitor Center, Harkers Island has served as a gateway to the lighthouse and the southern portion of the park. At a marina near the visitor center, a passenger ferry licensed by the National Park Service provides access to Shackleford Banks and the lower portion of Core Banks during spring, summer, and fall. (For more information on the national seashore, see The Cape Lookout National Seashore Tour, pages 3–32.)

From the waterfront park, walk to the end of the road. Here, at the confluence of Back and Core sounds, is Shell Point. This ancient tip of land holds clues to the history of Harkers Island. Evidence found in this area proves that the island was the site of human habitation for untold centuries. Well into the twentieth century, huge mounds of oyster, clam, scallop, and conch shells left long ago by the Coree Indians were dominant landmarks.

Excavations at the mound in 1928 unearthed three Indian skeletons. On other occasions, teeth, bones, pipes, arrowheads, clubs, tomahawks, and various pieces of Indian pottery have been discovered in the pile of shells.

One piece of Indian pottery is reported to have the word CROATOAN carved upon it, leading some island residents to claim that Harkers Island was the location of the Lost Colony. CROATOAN was the word John White and his men found carved in a tree on Roanoke Island when they returned from England in 1590 and discovered the colony deserted. Although no other tangible evidence has been brought forth to support their claim, numerous historians have concluded that Manteo, the Indian friendly to Sir Walter Raleigh’s colonists, was indeed born on Harkers Island.

Conjecture aside, the shell mound covered at least three acres when the first white settlers took up residence on the island. Since that time, it has been significantly reduced in size. So substantial were the shells that Confederate soldiers constructed a horseshoe-shaped fort at Shell Point.

Around 1920, hundreds of tons of the shells were ground up for fertilizer and used on Hyde County farmland. At about the same time, huge quantities of shells were removed and transported to Hyde, Pamlico, and Carteret counties for use in road construction. Apparently, the Indians who were responsible for the mound had discovered many years earlier that shells could be used to build roads. Using shells, they attempted to construct one of the earliest causeways in North Carolina, from Shell Point to Shackleford Banks. Remnants of this early engineering effort can still be traced on the bottom of Back Sound.

In 1926, vast quantities of shells from the mound were used in the construction of the first hard-surfaced road on Harkers Island.

Yet even after all these projects started depleting the mound, it still measured ten to fifteen feet high and extended into the water about seventy-five yards.

From the days of the earliest European explorations along the North Carolina coast, Harkers Island has been known by several names: Crane Island, Craney Island, Davers Island, and Marker Island. Thomas Sparrow acquired the island by grant on March 21, 1714. Ebenezer Harker subsequently purchased the island in 1730 for four hundred pounds. At that time and for the next half-century, the island was known as Craney Island. Ownership of the island eventually fell into the hands of three Harker brothers, who in 1783 gave it their last name.

Until the late nineteenth century, the island was sparsely populated. Dense, junglelike thickets and virgin forests of oak, pine, cedar, and yaupon made travel from one end to the other almost impossible. Several small settlements grew in clearings at the edge of the wilderness.

In August 1899, the island’s population more than doubled with the arrival of refugees from the terrific hurricane that lashed Diamond City and the other barrier-island villages just across the sound. Many current residents of Harkers Island trace their ancestry to the “Ca’e Bankers.” (For more information on the evacuation of Diamond City, see The Cape Lookout National Seashore Tour, pages 29–32.)

From Shell Point, retrace your route on Harkers Island Road to the bridge.

Before the turn of the century, travel on the island was limited to the shoreline. At high tide, the only way to get from one end of the island to the other was by boat. Around 1900, island residents banded together to cut a narrow path that ran the length of the island. Gradually, this path evolved into the existing east-west road.

When the United States Post Office Department opened a post office at Sea Island—the name arbitrarily assigned to the island—on December 3, 1904, mail was delivered by boat. After the islanders were united by a road, they began to seek improved access to the mainland. An unscrupulous automobile dealer promised a group of Harkers Island men that the government would build a bridge from Beaufort to the island if they would buy at least fifteen automobiles. Not until ten vehicles had been purchased did the naive men realize that the promise was a hoax. They were left with automobiles they could use only on rare occasions.

When the county took over road maintenance in 1926, access to the island began to improve. A north-south road was built to link sea to sound, and a ferry operation between the island and the mainland community of Gloucester was instituted. In the late 1930s, a visitor from inland mistakenly thought he was on U.S. 70 and drove his automobile down the ferry road and into the water. Several occupants of the vehicle drowned, creating a public outcry for a bridge, which was completed in 1941.

Return to Straits on S.R. 1335, then continue 1.9 miles as the road loops south to Gloucester. Named for the coastal town in Massachusetts, this tiny settlement overlooking The Straits has less traffic than it did a half-century ago, when the ferry to Harkers Island departed from the Gloucester waterfront. During the Revolutionary War, a saltworks operated in the village.

To continue the tour, proceed 1.2 miles on S.R. 1335 as it loops north to the intersection with S.R. 1346. Turn right on S.R. 1346 and drive 0.9 mile to Marshallberg.

Of the many great pleasures awaiting visitors to the North Carolina coast, one of the most rewarding is the discovery of an out-of-the-way place where the romance of the sea lives. The mainland shore of Core Sound is one of those places. Marshallberg is the first of many salty Down East communities on the remainder of the tour, which clings to Core Sound for almost 40 miles.

Up and down the North Carolina coast, much of the mainland waterfront has been deemed virtually uninhabitable since the arrival of the first white settlers in the sixteenth century. However, Down East Carteret has been an exception. Here, the interior coastline, punctuated by numerous rivers, bays, and creeks, has been the site of prosperous farms and fishing settlements for more that 250 years.

Marshallberg, one of the most eye-appealing Down East communities, rests on a spit of land bounded by Sleepy Creek and Core Sound. When the first white settlers arrived here around 1800, they found evidence of the existence of a large Indian village at the site. Since that time, many Indian graves have been uncovered. Among the relics are pottery, stone weapons, and large shell mounds similar to, but smaller than, the ones at Harkers Island.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, Marshallberg was known as Deep Hole Creek, a reference to the deep hole left by workmen who excavated swampy soil for use in the construction of Fort Macon on Bogue Banks. A post office opened in the village on February 17, 1889, under the name Marshall. It was so named by the less-than-modest first postmaster, Matt Marshall.

On the picturesque waterfront at Marshallberg, a spectacular panorama of Core Sound awaits visitors. Named for the Coree Indians who once inhabited the area, the sound is one of the most beautiful bodies of water on the North Carolina coast. Though it is relatively narrow—generally no more than 3 nautical miles in width—it is approximately 28 miles long, stretching from Pamlico Sound in northern Carteret County to the bight at Cape Lookout. Probably the most interesting geographic feature of the sound is its lack of depth. Boaters cruising these waters pass by local fishermen standing in the middle of the sound in search of clams.

Some ancient maps lend credence to the local belief that a long, slender island once existed in the middle of the sound. Such an island would explain the shallow depths.

Although Harkers Island is now said to be the center of Down East boat building, the shallow-draft boats that brought fame to the area were first constructed at Marshallberg. George Milney, a New England native, brought the first “sharpie” to the community in the 1880s. Local fishermen discovered that this sailboat, with its high bow and rounded stern, was perfect for the shallow waters of Core Sound. Island craftsmen improved the buoyancy of the sharpie by flaring its bow and exaggerating its fantail. The resulting craft became known as the “Core-Sounder.” Boatyards at Marshallberg, Harkers Island, Hatteras, and other places on the North Carolina coast still produce this type of boat.

Numerous well-preserved, whitewashed, turn-of-the-century homes grace the streets of Marshallberg. More than six hundred people live in the community, making it one of the largest Down East villages.

In Marshallberg, S.R. 1346 merges into S.R. 1347. Drive north on S.R. 1347, which tightly hugs the sound for 2.4 miles until it rejoins U.S. 70 at Smyrna.

Situated at the head of Middens Creek, the fishing village of Smyrna boasts 650 residents and is believed to be the oldest settlement in the area. It was named for Smunar Creek in 1785, but the spelling changed over the years.

For more than 140 years, Smyrna has been the center of education in this part of Down East. A one-room school opened in the village in 1850. County funds were used to build a large school building with an auditorium in 1914, and a consolidated high school was completed around 1922. At present, Smyrna Elementary School draws students from Smyrna, Marshallberg, Gloucester, Straits, Otway, Bettie, Davis, and Williston.

At Smyrna, turn north off S.R. 1347 onto U.S. 70. It is 2.6 miles to Williston. This old fishing community rests peacefully on the shores of Jarrett Bay and Williston Creek. For many years, the only bridge in the village was a four-foot-wide drawbridge spanning the creek. It was subsequently widened to accommodate vehicular traffic.

From Williston, continue 3.5 miles on U.S. 70 to Davis. En route, you will cross still another bridge, one of a dozen or more between the North River and Cedar Island. These water crossings are visual reminders of the difficulties encountered earlier in the century by the builders of the highway through Down East and the settlers who preceded them. Each of these bridges yields a magnificent vista of green marshland and placid bays and creeks.

Of all the Core Sound communities, Davis is the least changed by the passage of time. It is one of the oldest of the settlements, tracing its roots and name to William Davis, who received a grant of 360 acres from King George II in 1763.

Davis lies directly on the shore of Core Sound at the midpoint of a dogleg peninsula formed by Jarrett Bay and Oyster Creek. Prior to the construction of the highway from Beaufort, this village and those to the north were completely isolated from the outside world except by water travel.

Geographic isolation played an important role in a dramatic true story that symbolizes the courageous spirit of the residents of the North Carolina coast. Local people refer to the event as “the Miracle at Davis.”

The hardy villagers were accustomed to harsh winters, but no one was prepared for the winter of 1898. Cold weather came early that year, and as it grew harsher, Davis residents found themselves caught in the grip of the coldest winter ever recorded in the area. Food supplies were depleted; fowl that were hunted in happier times sought refuge in warmer climates; and boats could not get out of the harbor because ice choked the sound.

During the bleakest, coldest part of the winter, Core Sound froze solid from the mainland to Core Banks. Many residents became ill. Passage over land for help was impossible. A sense of futility spread through the settlement. In an act of desperation, Uncle Mose Davis, a black leader in the community, recommended that the villagers hold a prayer meeting. All able-bodied people assembled north of the village on the banks of Oyster Creek, where Mose Davis led them in a simple, beautiful prayer: “O Lord, we’re gathered here to ask you to help us out of our troubles. We’ve done everything we can for ourselves, and unless you do something to help us, we are all gonna starve to death. Amen.”

Almost as soon as Uncle Mose raised his bowed head, he saw a column of smoke stretching into the eastern sky. Everyone in attendance immediately recognized the smoke as a signal for help from Core Banks. An intense debate followed. Some villagers argued that it would be tantamount to suicide to attempt a rescue. No boat could get through the ice, and, if walked upon, the ice would likely crack, sending a would-be rescuer to certain death. Finally, Uncle Mose chided the reluctant members of the group by asking them how they could ask God for help if they were unwilling to help others in need.

Goaded into action, the rugged seamen of the village tied three lines to the bow of a twenty-foot skiff. Then three brave individuals attached the lines to their waists and began pulling the boat on the ice behind them. They slipped and struggled on the 3-mile sheet of ice, but it proved thick enough to support their weight.

When the rescuers reached Core Banks, they hurried to the top of the dunes, from where they could see a group of stranded sailors huddled around a fire on the beach. Their ship, the Pontiac, had wrecked on the nearby shoals. After caring for the victims of the wreck, the Davis residents went about salvaging the ship’s cargo. They were delighted to find vast stores of molasses and grain. Because of their efforts to rescue seafarers in trouble even in the face of personal danger, the people were saved from starvation.

Furnishings salvaged from the captain’s cabin of the Pontiac now decorate a Williston home.

Because of Davis’s expansive waterfront on Core Sound, pleasure boaters have made the village one of the favorite ports of Down East. Several marinas and boat landings are in evidence on the waterfront.

The present population of the village is approximately five hundred.

Davis counts among its favorite sons William Luther Paul, born in the village on October 8, 1869. It is believed that Paul was experimenting with a flying machine similar to a helicopter at the time the Wright brothers achieved their success at Kill Devil Hill in 1903. Due to the isolation of Davis, Paul was never able to obtain an engine with enough power to lift his invention into the air. Local historians claim that Igor Sikorsky used Paul’s model in the development of the helicopter.

Continue north from Davis. U.S. 70 crosses Oyster Creek during the pleasant 3.6-mile drive to Stacy. This picturesque community of three hundred inhabitants rests on a low, marshy area called Piney Point. No spot in the village rises more than five feet above sea level.

At the waterfront, you will see evidence that Stacy, like most Down East villages, owes its heritage to, and hinges its future on, fishing. Generations of Stacy residents have gone to the sea in boats.

Long before remote coastal villages received advance warning of hurricanes, fishermen had to depend on savvy and raw nerve to survive the horrible storms that often blew up out of nowhere. Lessons learned from a tragic storm in August 1899 have been handed down to successive generations of local fishermen.

On the morning of August 15, a group of fishermen from Stacy and nearby Sea Level set sail for Swan Island, located near the mouth of the Neuse River in Pamlico Sound. They were completely unaware of the massive hurricane, later named San Ceriaco, that was fast approaching from the Caribbean. When the storm struck the Core Sound area two days later, some of the fishermen decided to make the 10-mile run home. But when they were 3 miles into the voyage, the storm swamped their vessels with a twelve-foot wall of water.

All men on board lost their lives. Months passed before the bodies of the victims, save one, were found. Ten wives became widows, and twenty children were rendered fatherless. Now, almost a century after the calamity, the people of Down East maintain a healthy respect for approaching storms.

Beyond Stacy, the highway closely follows the waters of the sound and Nelson Bay as it heads to the three remaining Down East villages. It is approximately 1.5 miles to Masontown, the smallest of the three. This tiny fishing hamlet has a few stores and churches.

Three miles from Masontown, the highway forks. U.S. 70 veers sharply southeast onto a beautiful peninsula bounded by sound and bay, and N.C. 12 makes its way north to Cedar Island. At the fork, continue on U.S. 70 for 1.4 miles. Turn right on S.R. 1373. After 0.2 mile, turn right on S.R. 1385 and proceed 1.5 miles as the road loops around the shore of scenic Nelson Bay. Nestled on the southern tip of the peninsula is the village of Sea Level (or Sealevel), unequaled in charm and beauty in Down East.

Although no one knows why the village was originally called Whit, the name was still in use when a post office was established here on March 11, 1891. Whit became Sea Level twenty-four years later.

Around the turn of the century, four sons were born into the Taylor family, an old family in the village. Daniel, William, Alfred, and Leslie Taylor grew up learning the ways of the sea and acquiring a genuine love for the people of Down East. As adults, the brothers became extremely successful businessmen. Their lucrative commodity brokerage maintained offices in Norfolk and the North Carolina towns of Wilmington, New Bern, and Washington. Despite the wealth they accumulated, the Taylors never forgot their roots in Sea Level. To facilitate access to Ocracoke from their old hometown, they purchased a ferry and operated it between the nearby village of Atlantic and Ocracoke until the state assumed control of the route.

Their concern for the medical needs of the residents of the small coastal communities led the brothers to build a seventy-six-bed hospital at Sea Level. In 1951, this long, one-story facility on the shore of Nelson Bay was dedicated by the Taylors as a memorial to their friends in the area. Homes for staff, a pier, and a motor inn to accommodate hospital visitors were constructed to complete the medical complex. Over the years, the inn has become a popular overnight stop for people taking the early-morning ferry to Portsmouth and Ocracoke islands.

In 1969, the Taylor Foundation donated Sea Level Hospital to Duke University for operation by Duke Medical Center. During the 1970s and 1980s, the university gradually converted sixty of the seventy-six acute-care beds to extended-care and nursing-home use. In February 1991, the long-feared decision to close Sea Level Hospital was announced by Duke University. Although many Down East residents realized that the hospital did not draw enough patients to make it profitable, a desk clerk at the Sea Level Inn expressed their lingering sentiment: “If the Taylor brothers were still here, it wouldn’t have closed.”

Following the termination of hospital operations, the old facility was turned over to Carteret County for use as a nursing home.

Despite its small size and isolated location, Sea Level is the home of a nationally known institution. Sailors’ Snug Harbor, a retirement home for merchant sailors, relocated to Sea Level from Staten Island in 1976 after an extensive legal battle in New York.

Opened in 1833 on Staten Island’s Kill Van Kull, Sailors’ Snug Harbor has a fascinating history. It was the brainchild of Captain Robert R. Randall, who earned a fortune from privateering during the Revolutionary War. Upon his death in 1801, his will, penned by his famous friend Alexander Hamilton, established a trust to provide a home for “aged, decrepit, and worn-out sea-men.” His trust was funded with twenty-one acres in the middle of what became Greenwich Village. Much of the property is still owned by the trust, and rent from it provides income for the operation of the home.

The Sailors’ Snug Harbor facility was built on an eighty-acre site on Staten Island. It grew substantially during its 143 years of operation in New York. At one time, there were seventy major buildings with a capacity for nine hundred retired and disabled seamen.

In the late 1960s, mounting difficulties with the Staten Island location caused trustees to begin a search for a new site for the home. Negotiations with the Taylor family for a tract at Sea Level began in 1971. Once New York authorities learned of the decision to move the facility, the state attorney general filed suit to block the relocation on the grounds that the charter for the home stipulated that it “overlook the East River or vicinity.” The legal dispute was settled in late 1972 with an agreement whereby fifteen acres of the original Staten Island site were transferred to the city of New York for use as a park.

At Sea Level, new facilities were constructed on a 105-acre site. Built to house 122 retirees, the complex features a 100,000-square-foot brick building containing a private room for each resident, a forty-bed infirmary, a physical-therapy center, and a cafeteria. All the artwork and artifacts from the former New York facility are housed at the current home.

Without any advertisements, the home received more than six hundred applications from prospective residents in its first seven years of operation at Sea Level. Admission requirements are few: applicants should have at least ten years of merchant service at sea and a need for a retirement home. In 1981, for the first time, the facility began charging newly admitted residents 40 percent of their income to help defray ever-increasing costs.

At the Sea Level waterfront, turn left, or north, off S.R. 1385 onto S.R. 1373 and drive 1 mile to the intersection with U.S. 70. Turn northeast and proceed 2.5 miles to where U.S. 70 ends at the town of Atlantic.

Oddly enough, the town at the end of the long, serpentine highway is among the most populous of the Down East settlements. Close to a thousand people live in this village, where generations of residents have made their living from the sea.

Throughout Atlantic’s long history, other forms of employment have come and gone, but fishing has remained constant. Many residents worked as guides and lodge keepers when duck hunting was popular in the area in the late nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth century. The popularity hunting once enjoyed in the Atlantic area is evident from the town’s earlier name: Hunting Quarters.

Historians believe that the first white settlers arrived in the Atlantic area as early as 1740. Over the years, the villagers developed a keen interest in education. In 1896, the Atlantic Academy opened as the first high school in Carteret County. The town was incorporated in 1905.

In the aftermath of World War II, Atlantic gained a well-deserved reputation for the commercial seafood it produced. By 1954, the town had become one of the largest seafood producers in the state. Today, its waterfront seafood dealers boast of selling the freshest seafood anywhere.

Motorists who venture to the northern reaches of Down East are delighted to find this comfortable, picturesque village near the end of their trail. It is perched on a bluff overlooking Core Sound, Thorofare Bay, and Styron Bay. Myrtle, yaupon, and wind-stunted oak trees grow in the yards of the tidy homes set at odd angles along the winding village streets.

In Atlantic, turn northwest off U.S. 70 onto S.R. 1387. It is 2.9 miles to the junction with N.C. 12. Along this route, the remnants of a World War II landing field used by the United States Marines are visible.

Turn right, or north, onto N.C. 12, which will carry you to the far corner of Down East Carteret. One mile into the journey, you will cross the Thorofare, a channel that connects Pamlico and Core sounds and separates Cedar Island from the mainland.

Cedar Island is bounded on the west by Long Bay, West Bay, and North Bay—arms of the western section of Pamlico Sound. A cluster of islands in Pamlico Sound forms the northwestern boundary. Core Sound lies to the east.

Covering more than 17,000 acres, the island is a vast untamed wilderness, inhabited only on its northern fringes. Almost 80 percent of Cedar Island has been saved from development by its inclusion in the Cedar Island National Wildlife Refuge. Established in 1964 as a nesting and feeding area for migrant and wintering birds, the refuge encompasses some 13,700 acres of irregularly flooded salt marsh and woodlands. The island’s hummocks and ridges are covered by red cedar, pine, and gum trees. More than 270 species of birds can be observed throughout the refuge, which is a major breeding area for black rails.

Although the refuge is undeveloped, N.C. 12 runs through it, and other roads provide access to its interior. Approximately four thousand acres of the refuge have been set aside for hunting. Boat landings are located at the bridge over Thorofare Bay and Lewis Creek. Group tours can be arranged at the refuge headquarters, which is located on S.R. 1388 on the northern end of the island.

For nearly 5 miles north of Thorofare Bay, N.C. 12 passes through a desolate grass savanna that stretches as far as the eye can see on both sides of the highway. Because of the rugged, forbidding appearance of the landscape, it is difficult to imagine how humans have survived for centuries at this isolated outpost. Nevertheless, artifacts found on the island and in the surrounding waters disclose that Indians lived in the area many centuries ago. Well into the twentieth century, large mounds of shells similar to, but not as large as, the ones at Shell Point on Harkers Island were found on Cedar Island and nearby Hog Island. When they were excavated for use in road construction, the mounds yielded human and animal skeletons. At low tide, fragments of Indian pottery are often found on the island beach.

Between 1650 and 1700, the first literate white settlers began to make their home on Cedar Island. Strangely enough, these settlers discovered white people already living there. A large Indian population also inhabited the place. Harmony existed between the two groups, some of their number living together as neighbors.

Though the existing white inhabitants spoke English, none of them could read or write. Their lifestyle was that of the Indians, rather than that of Anglo-Saxon Europe. Upon being questioned about their roots, the mysterious people answered that they had always lived there. For many, many years, historians and the residents of Down East have struggled to solve the mystery surrounding the early white residents of the island.

Throughout the recorded history of Cedar Island, families bearing last names identical to those of members of the Lost Colony have lived here. Accordingly, some amateur historians have speculated that Cedar Island may have been home to the Lost Colonists. An ancient oak tree which formerly stood in Croatan National Forest may have been a tangible piece of evidence to support the theory. Early in this century, Ellis Fondrie, a Carteret County native, discovered the giant tree, which bore the letters C-R-O-A-T-A-N. The letters had either been burned or carved into the bark. Unfortunately, the tree was destroyed by lightning prior to World War II.

At the northern end of Cedar Island, N.C. 12 veers sharply to the northwest. After approximately 6.2 miles on N.C. 12, turn east onto S.R. 1388 for a 2.4-mile drive to the eastern shore of the island.

Despite its size, the island has never supported a large population. In the nineteenth century, two separate communities 4 miles apart developed on the northern shore. The remnants of the village of Lola are located along S.R. 1388.

Retrace your route to N.C. 12 and continue in your original direction. Roe, Lola’s sister village, is located in this section.

It is 3.5 miles to the landing of the state-operated Cedar Island-Ocracoke Ferry. Virtually all of the five hundred or so residents of Cedar Island live along the highway near the landing. The Cedar Island docks were constructed in 1964. Since that time, the route has ranked as one of the most popular in the state ferry system.

Several small islands with interesting histories of human habitation are visible from the northern shore.

Hog Island—actually a cluster of sound islands grouped between Back Bay and Pamlico Sound—is the site of Lupton, now a ghost town. A post office operated in the now-deserted village until May 15, 1920.

Located northeast of Lupton, Harbor Island has been greatly reduced by erosion over the past century. In 1867, a screw-pile lighthouse was built on the island to facilitate navigation of Core Sound. A hurricane subsequently destroyed the lighthouse, and no trace of it remains today. In the 1930s, a hunting and fishing club was constructed on the western tip of the island. The ruins of the old clubhouse are still visible.

Horse Island, located in the northern portion of Core Sound, also contains the ruins of a clubhouse. For many years, the island has been the source of eerie stories. Two persons are said to have been murdered there. Fishermen have reported seeing ghosts roaming the island.

The tour ends here, at the northern tip of Cedar Island.