This tour begins at the intersection of U.S. 70 and Turner Street in the historic port town of Beaufort. Proceed south on Turner Street to the Carteret County Courthouse, located in the first block.

This tour examines the historic district of the old port town of Beaufort, beginning and ending at u.s. 70.

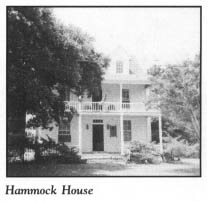

Among the highlights of the tour are the Old Town Restoration Complex, the North Carolina Maritime Museum, the Old Burying Ground, the story of Nancy Manney French, the colorful Beaufort waterfront, the Rachel Carson National Marine Estuarine Sanctuary, the horses of Carrot Island, and the historic homes of Beaufort, including Hammock House.

Total mileage: approximately 4 miles.

Beaufort-by-the-Sea, as the town is romantically called, is a place of historic distinction. While most historians have recorded that Beaufort is the third-oldest town in North Carolina, there are some who contend it is the second-oldest. Regardless of its rank, the ageless town has written a captivating history that now spans almost three hundred years.

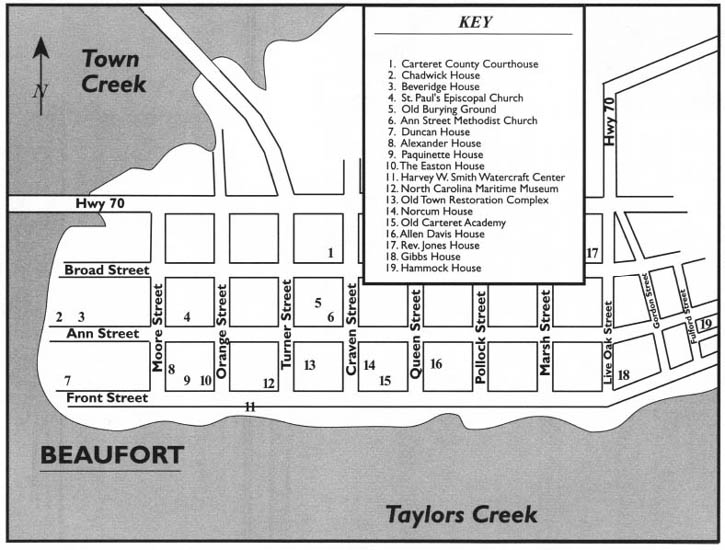

Records inside the Carteret County Courthouse date back to 1713. The imposing 1907-vintage structure is the fourth courthouse to serve the county. Designed by a New Bern undertaker, it features huge Corinthian porticoes on the southern and western sides, granite arches with keystones, and an octagonal, copper-clad cupola.

In 1983, the Carteret County commissioners considered demolition of the dignified red-brick structure because of age and deterioration. Pressure from historical groups persuaded the governing body to spare the Neoclassic Revival building. A modern annex was subsequently connected to the original structure, marring its appearance.

From the courthouse, continue south on Turner Street.

If you have never been to Beaufort before, it will soon become apparent that this is a rare and special kind of place. Simply put, it is hard for anyone not to like the old port town. Included among its treasures is a magnificent historic district containing one of the finest concentrations of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century homes for a town its size in all of America. Beaufort also boasts a world-class maritime museum, a fully accessible waterfront affording spectacular views of nearby Carrot Island and its herd of wild horses, and a compact business district chock-full of interesting antique and gift shops, ship’s stores, and restaurants.

Beaufort residents are proud of their town’s splendid ensemble of historic structures. The majority of the old homes of Beaufort are privately owned. Some of the buildings have survived wars and invasions, storms, and pangs of modernity for more than two centuries. This superior collection of more than 120 historic treasures is located in a 3-block-by-11-block area south of U.S. 70.

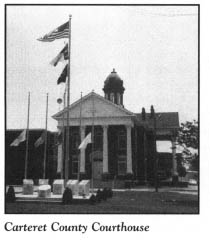

It is 2 blocks from the courthouse to the Old Town Restoration Complex. Operated by the Beaufort Historical Association, this complex of restored homes, cottages, shops, a jail, and a courthouse provides an opportunity to inspect and appreciate the distinctive architecture of Beaufort. Among the holdings are the Joseph Bell House, considered by many to be the finest house in town. Constructed in 1767, this frame house, painted conch red, was restored in 1966.

The headquarters for the complex are located at the Josiah Bell House. Constructed in 1825, this home contains a number of interesting rooms furnished with Victorian pieces.

Also located on the beautifully landscaped grounds is the Apothecary Shop/Doctor’s Office, constructed around 1859. Authentic medical instruments, bottles, and prescription files used in early country medicine are exhibited inside.

The nearby R. Rustell House, constructed in 1732, houses the Mattie King Davis Art Gallery.

Two former government buildings are also maintained as part of the complex.

The Carteret County Courthouse of 1796 is the oldest existing public building in the county. Prior to that year, the Church of England used the small frame building as a meeting place. During the War of 1812, this old courthouse quartered American troops from Beaufort, Lenoir, and Craven counties. Today, a rare, original thirteen-star American flag is displayed in the building.

Adjacent to the former courthouse is the architecturally perfect building which once served as the Carteret County Jail. Constructed in 1836, the two-story masonry structure now contains several cells, the jailkeeper’s quarters, and a small museum.

Guided tours of the Old Town Restoration Complex are available, and special programs and activities are scheduled throughout the year. A tour of the complex provides an excellent opportunity to reflect upon the long, storied history of Beaufort.

Around 1708, the site now occupied by the town was settled by French Huguenots and immigrants from Germany, Sweden, England, Scotland, and Ireland. At their arrival, the place was known to the Indians as Wareiock, meaning “Fish Town” or “Fishing Village.” On early maps, the site appears as C. Wareuuock. Archaeological evidence indicates that Indians used the area as fishing grounds.

In keeping with the Indian tradition, the earliest white settlers called their community Fishtown. Beaufort emerged from Fishtown in 1713 when Robert Turner surveyed and platted two hundred acres between the Newport and North rivers. Original plats show that his pattern of streets remains virtually intact today. Henry Somerset (1684–1714), the duke of Beaufort, one of the Lords Proprietors, was the town’s namesake.

Although its early growth was sluggish, Beaufort possessed an asset which attracted the attention of the colonial government. Its magnificent harbor along Taylors Creek made the town a natural choice as a port, and in 1722, Beaufort was formally designated a port of entry.

About the same time, there were other indications that Beaufort was coming into its own. Carteret was made a precinct in 1722, and Beaufort immediately became the seat of local government, a distinction that it continues to enjoy today. A year later, Beaufort was officially incorporated by the colonial assembly.

Early residents were constantly alarmed by the failure of the colony to provide coastal defenses against pirates and the ships of foreign navies. On August 21, 1747, Beaufort residents watched in horror as the Spanish fleet sailed into the harbor. After planting the flag of Spain, the sailors occupied and pillaged the town for several days. They were finally chased away by the militia and local farmers.

After the Spanish threat was quelled, Beaufort was able to turn its attention to commercial development. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the town had become the third-largest port in the colony, behind only Brunswick Town and the unnamed port on Albemarle Sound. By the early 1770s, approximately sixty families were living in the town.

Beaufort residents were filled with patriotic fervor at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. As a consequence, the town played a leading role in the quest for American independence.

To supply the wartime need for salt, several facilities were built in and around the town in 1776 to produce the commodity from boiled seawater.

Through its blockade of the major colonial ports, the British navy sought to choke off vital supplies intended for George Washington’s army. By providing a base for privateers and a port for Spanish and French sailing ships, Beaufort made its greatest contribution to the struggle for independence. Both the port town and Beaufort Inlet were unprotected for the duration of the war, but somehow the port remained open to serve as a vital supply line for the American cause.

It was not until after the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown that British forces attacked Beaufort. Several British warships sailed through the inlet and docked at the town on April 3, 1782. Landing troops pillaged and burned for several days. Townspeople, enraged by the attack, fought back. Finally, the determined patriots were able to cut off the invaders’ supply of fresh water. Discouraged and defeated, the warships sailed for Charleston on August 18. This skirmish has been called the last battle of the American Revolution.

Beaufort entered the nineteenth century as one of the most prosperous commercial and governmental centers in the state. In the early 1800s, wealthy planters began to bring their families to live in Beaufort townhouses to sample the happy lifestyle and enjoy the healthy environment. Thus, the local resort industry was born. Many of the beautiful white homes that now grace the streets of Beaufort were built during the prosperous years of the early nineteenth century.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Beaufort had a population of more than sixteen hundred. On March 25, 1862, the town fell under Union occupation. For the duration of the war, it served as an important base of operations for the Union offensive in the South. It was from Beaufort that the most formidable naval fleet ever assembled in the history of the world sailed in early January 1865 to deliver the death blow to the Confederacy at Fort Fisher.

One of the great ironies of the Union occupation of Beaufort was that the father of President Lincoln’s secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton, was born on the shores of nearby Core Creek.

Beaufort emerged from the Civil War relatively unscathed, and it quickly positioned itself as an important commercial port and summer resort. A profitable menhaden processing plant began operation near town in 1881. For many years afterward, the port was the home of a large fleet of menhaden boats.

Between the world wars, the town changed very little. By 1940, Beaufort counted almost three thousand residents, but its appearance resembled that of a nineteenth-century seaport, its waterfront dominated by the tall crow’s-nests of the menhaden fleet.

Beaufort entered a period of serious decline in the 1960s. Buildings on the ancient waterfront were rotting; shopping centers on the outskirts of town had begun to lure businesses from the downtown area; and suddenly, the once-abundant supply of menhaden was no more.

At the height of its decline in the 1970s, the town embarked on a path toward a remarkable recovery. Beaufort residents worked tirelessly to beautify and preserve their ancient village. Decaying buildings on the waterfront were removed in order to reveal the splendid beauty of Taylors Creek and nearby Carrot Island. A spacious boardwalk was built along the waterfront. Businesses in the form of gift and antique shops, bookstores, and art galleries returned to Front Street. An active Beaufort Historical Association spearheaded the drive to identify and preserve the 120 historic structures in town. As a consequence of these developments, Beaufort has been able to realize its potential as a tourist attraction without sacrificing its charm.

Continue south on Turner Street from the restoration complex to the waterfront. Turn right, or west, on Front Street to visit the North Carolina Maritime Museum, located at 315 Front Street. Parking is available to the rear and side.

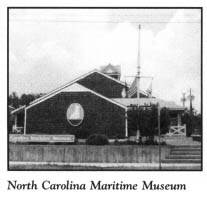

Beaufort is proud to be the home of one of the fastest-growing maritime museums in the nation. On May 18, 1985, the North Carolina Maritime Museum opened the doors to its new permanent home. Constructed at a cost of $1.5 million, the handsome building is an architectural blend of nineteenth-century Beaufort and the stations of the United States Lifesaving Service. The museum is covered with cedar shakes, a tradition on the Outer Banks, and adorned with a widow’s walk.

Though the hundred thousand visitors who tour the facility annually would never suspect it, the museum, long known as the Hampton Mariner’s Museum, had a pillar-to-post existence until recent years. It had its beginnings in the late 1930s with a crude collection of fish models and similar items assembled by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service at nearby Pivers Island. In 1951, the state acquired the museum’s holdings. Over the next quarter-century, while the collection was growing, the museum was moved to several different locations.

North Carolina yellow pine treated with flame retardants was used throughout the interior of the spacious, new 18,000-square-foot building that now houses the museum. Laminated, exposed heavy-beam construction gives visitors the sensation of being in the hold of a large wooden ship. Ceilings reaching to thirty feet enable the museum to house sailboats.

The exhibits are many and varied. The world-class shell collection is so large that only parts of it can be exhibited at one time. Aquariums filled with sea life are popular with patrons of all ages. In addition to the massive exhibit hall, the museum features a reference library, a bookstore, and an auditorium. Mariners and coastal researchers enjoy the elegantly apportioned library, which offers a wide variety of reference books on marine topics, as well as some rare volumes. Among the treasures are a Dutch book on shipbuilding dating from the 1600s and a century-old copy of “Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” illustrated with elaborate woodcuts. Classes and large events are held in the two-hundred-seat R. J. Reynolds Auditorium, the walls of which are decorated with coastal scenes painted by Winston-Salem artist Robert B. Dance.

Located directly across Front Street from the main building is the Harvey W. Smith Watercraft Center. This unique waterfront facility, dedicated to the preservation of the wooden craft and boat-building techniques indigenous to North Carolina, houses the museum’s boat shop and displays restorations and reproductions of traditional wooden boats.

Two annual events sponsored by the museum grow more popular every year.

During the last weekend in September, the museum sponsors the Traditional Wooden Boat Show. The event features a wide variety of activities, including rowing, paddling, and sailing demonstrations. It is recognized as the largest gathering of wooden boats in the Southeast.

Held on the third Thursday in August, the Strange Seafood Exhibition showcases the culinary talents of coastal cooks, who serve seafood dishes ranging from those eaten by Indians and early settlers to experimental delicacies. From its beginnings in 1977, the event has grown from eighteen dishes sampled by 150 persons to more than fifty items served to a crowd of approximately 2,000. Among the dishes featured at past exhibitions were conch salad, sweet and sour stingray wings, sea urchin eggs, shark jelly, and deep-fried silversides. The event, the only seafood festival of its kind in the country, is so popular that the museum staff has found it necessary to limit the number of seafood samplers.

Continue west on Front Street. In the 2 blocks west of the museum, there are several houses of historic note.

Located at 229 Front, the Easton House is one of many Beaufort homes listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Twelve years after the house was constructed, it was purchased by Colonel John Easton, who led the town’s defenders against the British invaders in April 1782. Jacob Henry subsequently purchased the house. In 1808, Henry was elected to the North Carolina General Assembly, but a year later, he was challenged, because, as a Jew, he “denied the Divine Authority of the New Testament.” Henry’s dynamic speech in his own behalf and the ensuing debate drew national attention and became important in the crusade for religious freedom in the United States.

Located at 217 Front Street, the Paquinette House was built by a family of French Huguenots in 1768. Its foundation is made of old ballast stones. This house is of special interest because of its eighteenth-century air-conditioning system: an opening in the attic floor allows the cool summer sea breeze to be carried through the house.

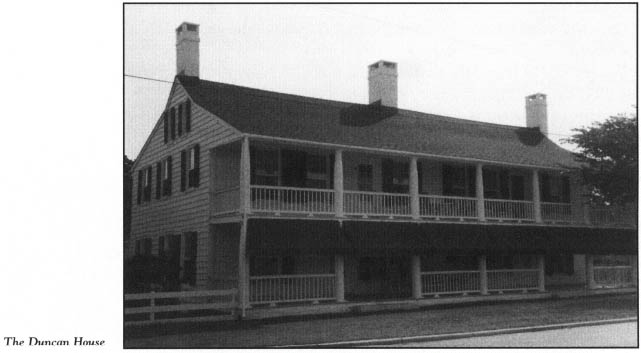

The Duncan House, located at 105 Front near the western end of the street, was built around 1790. It is an excellent example of the Beaufort gable-roof style. Most of the first houses in town were patterned after a style observed by local mariners in the Bahamas and the islands of the West Indies. Local craftsmen quickly modified the style to create the unique architectural style known as the Beaufort gable roof. Nearly seventy-five of the distinctive houses built in this style survive. They are distinguished by their unusual roof, which maintains a relatively steep pitch at the ridge and then breaks to a lesser pitch to cover porches in the front and bays in the rear. Homes built later, primarily in the middle of the nineteenth century, introduced the hip roof, common during the Greek Revival period.

Because of its waterfront location, Front Street boasts some of the most impressive homes in Beaufort. Unlike the large cities on the coast of the Carolinas, such as Wilmington and Charleston, Beaufort cannot claim a large array of sumptuous estates built by planters and wealthy merchants. Rather, much of the Beaufort townscape reflects its early days as a working seaport. The tidy white buildings tightly clustered throughout the original street grid of Beaufort present a unique view of the middle and working class of coastal North Carolina.

Retrace your route for 1 block on Front Street and turn north on Moore Street. After 1 block on Moore, turn left, or west, onto Ann Street.

Located at 123 Ann, the Beveridge House reflects the maritime heritage of Beaufort. John T. Beveridge, a native of Scotland, built the house in 1841. A sea captain, Beveridge was considered one of the most skillful navigators of his time. Although the house was moved many years ago from Orange Street to its present site, it is still owned by the Beveridge family. A number of interesting furnishings, including Captain Beveridge’s sea chest and a solid-oak bedroom suite brought back from the West Indies by Beveridge’s son, are found inside.

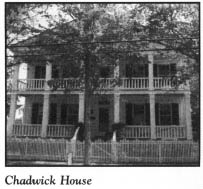

The Chadwick House, located at 117 Ann Street, is a stately, pedimented Greek Revival house constructed about 1858. Through the compassion of its former owners, Robert and Mary Chadwick, a young Chinese man was given an opportunity to achieve his true potential in the late nineteenth century.

Robert Chadwick was serving as collector of customs at the port of Wilmington in 1880 when Charles Jones, the captain of a United States revenue cutter, introduced him to the ship’s mess boy. Soong Yao-jo, as the eighteen-year-old lad was known, made a favorable impression on the Chadwicks. They adopted him and encouraged him to obtain an education.

Soong converted to Christianity, joined the Methodist Church, and enrolled at Trinity College, now Duke University. Upon his graduation, he studied religion at Vanderbilt University. Once his studies were complete, Soong went home to China in 1885 as a missionary of the Southern Methodist Church.

In China, he married and reared six children, all of whom were educated at colleges and universities in the United States. His most famous children were two of his daughters. One married Sun Yat-sen, the leader of the revolution that resulted in the founding of the People’s Republic of China. The other married Chiang Kai-shek, the longtime president of Taiwan.

From the Chadwick House, turn around and proceed east on Ann Street. St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, located on the north side of the 200 block, is considered one of the ten architecturally perfect buildings in the state. Much of the exterior and interior of the Gothic Revival edifice was constructed by shipbuilders. The most interesting of its exquisite stained-glass windows is the memorial window for Sallie Pasteur Davis, a niece of the famous French scientist Louis Pasteur. The cornerstone of the church is dated April 14, 1857.

On nearby Moore Street, the Alexander House, built around 1856, served as the rectory for St. Paul’s from 1890 to 1950. During that period, the rector’s daughter married North Carolina native Paul Green, the Pulitzer-winning playwright and author of The Lost Colony. The wedding was held in the church, and a reception followed in the garden of the rectory.

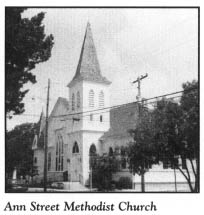

Continue east on Ann Street. Two blocks east of St. Paul’s, Ann Street Methodist Church stands proudly near the corner of Ann and Craven streets. This stately frame structure was completed in 1854 and remodeled in 1897. Intricately designed stained-glass windows highlight the sanctuary. When lit at night, the window on the Craven Street side radiates its message to passersby.

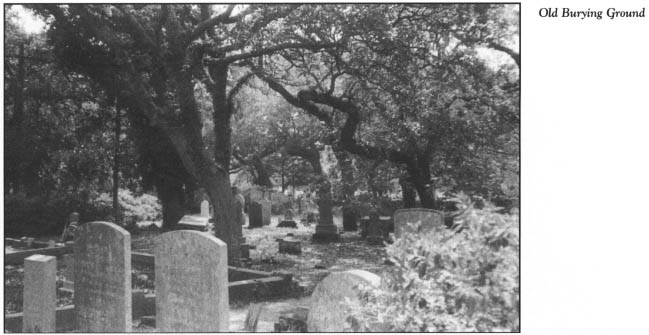

Of all the historic attractions in Beaufort, none is more interesting than the Old Burying Ground, located adjacent to Ann Street Methodist Church. This picturesque graveyard ranks as one of the oldest and most historically important cemeteries in the state.

Beaufort residents began burying their dead in this hallowed ground in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Although the cemetery site has always been deemed public property, it was officially conveyed to the town of Beaufort in 1731 by Nathaniel Taylor following an official survey.

Some of the first people laid to rest in the Old Burying Ground may have been hapless victims of the Indian wars in the second decade of the eighteenth century. Scores of the earliest burial spaces are covered with deteriorating cypress slabs, shells, or brick. Burial records were originally maintained by the Anglican Church, but these records vanished after being taken to Canada during the Revolutionary War.

There is no doubt that the oldest section of the cemetery is the northern corner. All of the graves in this section face east, because their occupants wanted to be facing the sun when they arose on “Judgment Morn.” Time and the elements have combined to obliterate the dates on some of the oldest grave markers. An inspection of the graves indicates that 1756 is the oldest legible date. However, that grave is hardly the oldest.

As a visitor to Beaufort in 1853, William Valentine described the Old Burying Ground as “the most beautiful place of the kind I ever saw, by far the choicest beauty spot of Beaufort.” Many visitors to the town more than 140 years later would still agree with Valentine. Encircled by three churches and enclosed by a handsomely crafted fence of masonry and metal, the cemetery offers an atmosphere of peace and tranquility. Ancient live oaks provide a canopy of shade over the sandy lanes and the tombstones.

Guided visits to the cemetery are included as part of the tour offered by the Old Town Restoration Complex. Self-guided tours are also permitted.

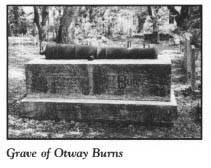

Almost every grave in the burying ground has an interesting story behind it. One of the most noteworthy persons buried here is the famous privateer and American hero of the War of 1812, Otway Burns. When he died on Portsmouth Island in 1850, his body was transported to Beaufort by boat. On July 4, 1901, Burns’s grandchildren unveiled the monument that now stands at his grave. A gun taken from his renowned ship, the Snap Dragon. surmounts the tomb.

As cruel as it may seem at first, the story behind the thirteen-year-old girl buried in a rum keg in the cemetery is actually a heartwarming tale of parental love.

This girl’s father and mother brought her to Beaufort from England when she was an infant. Her father became a prosperous merchant who made frequent trips to London. As the years passed, the child listened intently to her father’s stories about the exciting city of London. She longed to accompany him on one of his trips, but her concerned mother would not hear of it until the girl reached her thirteenth birthday.

Finally, the mother relented, but only after receiving assurances from her husband that the girl would absolutely be returned home to Beaufort. In London, the child and her father had a grand time, but on the return voyage, tragedy occurred. Fever killed the little girl. Officers of the ship made preparations to bury the child at sea in customary fashion, but the bereaved father persuaded them to allow him to keep his promise. He purchased a keg of rum from the cargo hold and sealed the lifeless body of his daughter inside. When the ship docked in Beaufort, the keg was buried on the Craven Street side of the cemetery. The impressive home of the little girl and her family, constructed in 1768, continues to grace the Beaufort waterfront at 209 Front Street.

No grave boasts a more touching story than that of Nancy Manney French, who was laid to rest in 1885 shortly after being reunited with her long-lost lover. It is a true story, yet it sounds like a plot conceived by Hollywood scriptwriters. Indeed, the tale of the bittersweet romance of Charles French and Nancy Manney reads like a legend.

Nancy Manney was a Beaufort girl, the daughter of a local physician. Charles French was a Philadelphia law student. Their paths first crossed when Nancy’s father lured Charles to Beaufort in 1836 to tutor his children. Nancy was sixteen at the time.

Charles spent two years teaching the Manney children. During that time, he and Nancy fell in love, but they kept their romance secret for fear of incurring the wrath of Dr. Manney. However, when the time arrived for Charles to resume his legal education, he revealed his love for Nancy and asked the physician to allow him to marry her upon completion of his studies. To his dismay, Charles was informed by Dr. Manney that the romance had not been a secret. The physician announced his stern disapproval and ordered Charles to end his relationship with Nancy and to leave town for good.

But as is the way with star-crossed lovers, Charles and Nancy pledged their eternal love. They vowed to marry someday. In the meantime, the couple agreed to write to each other to pass their tormented days of separation.

The infatuated pair faithfully penned love letters, but Dr. Manney made sure that none of the correspondence reached its destination. Determined to keep Nancy and Charles apart, the doctor prevailed upon the Beaufort postmaster to intercept all incoming and outgoing mail between the two. All of the letters were collected, tied in a bundle, and held secretly at the post office.

Days melted into years. Charles eventually stopped writing, assuming that Nancy no longer cared. To the contrary, Nancy’s love was unfailing. Though she heard nothing from Charles, Nancy continued to write, clinging to the faint hope that he would come for her someday.

Her father passed away, taking to the grave his terrible secret. However, when death came calling on the Beaufort postmaster, his years of guilt led him to call Nancy to his bedside. There, he detailed his sordid pact with her father. The letters at long last were given to Nancy, who was by then forty-five years old.

Nancy took the revelation with mixed emotions. Her love for Charles was as strong as ever. Knowing that he had not broken his promise was of great comfort, but she also had to face the realization that he had probably married someone else. She threw herself into the work of ministering to wounded troops during the Civil War.

Twenty years passed. Nancy did not marry. Suddenly, one day in 1885, she received word that the mail clerk at the Beaufort post office wanted to see her. A letter requesting information about the Manney family had arrived. It revealed that the writer had known the family many years before. He expressed a desire to visit Beaufort again if any members of the Manney family were living. The signature affixed to the letter was that of Charles French, the chief justice of the Supreme Court of the Arizona Territory.

Joyously, Nancy wrote Charles urging him to come to Beaufort and saying she still loved him. She was now sixty-five years old and seriously ill with consumption. Charles was a dignified but lonely old man. He had married another long ago after patiently waiting for Nancy’s letters. His wife had been dead for years.

Charles hurried to Beaufort. When his ship arrived at the waterfront, old friends greeted him, but Nancy was not there. She was sick in her bed. Her long-lost love hastened to her side. After nearly fifty years of heartbreak, the couple was reunited.

Once again, Charles proposed to Nancy. Once again, Nancy accepted. When their wedding day came, the aged groom knelt beside his ailing bride’s bed. He tenderly lifted her into his arms, and they became one.

Their long-awaited happiness ended a few days later, when Nancy died.

To continue the tour, proceed east 1 block on Ann Street, then turn right, or south, on Queen Street. Located on the eastern side of the street at 120 Queen, the Allen Davis House served as the headquarters for General Ambrose Burnside—the man for whom sideburns were named—during the Union occupation of Beaufort in the Civil War. The existing structure, an enormous Greek Revival house, is an enlargement of a small Beaufort cottage constructed in 1774.

Queen Street ends on the waterfront at Front Street. To experience the maritime atmosphere of Beaufort, park in the municipal parking lot on Front. This street is bordered by an interesting ensemble of stores and shops and the incomparable waterfront, which is the focal point of much of the downtown activity during spring, summer, and fall. A modern boardwalk separates the public boat docks from shops, restaurants, and parking facilities. Boardwalk strollers are awed by the luxurious pleasure craft from many distant ports that tie up at the docks on Taylors Creek. Since the waterfront was restored, Beaufort has become a favorite port for Intracoastal Waterway traffic.

Boat tours of the surrounding waterways and islands are available on the waterfront.

A four-foot granite monument erected on the boardwalk in July 1986 memorializes Michael J. Smith, a famous native son. America and the rest of the world watched in horror in January 1986 as the space shuttle Challenger exploded, killing the mission commander, pilot, and five-member crew. Smith, the pilot on the ill-fated mission, grew up in Beaufort.

Located across Taylors Creek from the Beaufort waterfront, the complex of small islands comprising Rachel Carson National Marine Estuarine Sanctuary stretches from Beaufort Inlet to the North River. Known nationwide by marine biologists and other scientists, the site is used for research and education. It is equally important to area residents and visitors as a recreation spot.

Carrot Island, Town Marsh, Bird Shoal, and Horse Island make up the western end of the sanctuary—that portion visible from the Beaufort waterfront. Combined, these islands are almost 3.5 miles long, covering 2,025 acres. On the eastern end, Middle Marsh, almost 2 miles long and 650 acres in size, is separated from the other islands by the North River Channel.

Coree Indians are thought to have used Carrot Island and Middle Marsh prior to the arrival of the first European settlers. Early residents of Beaufort built wharves on Carrot Island, from which they shipped lumber, naval stores, and fish and farm products. In the early eighteenth century, Carrot Island was known as Cart Island. Fishermen unloaded their nets on its southern side. A causeway of ballast stones was constructed across Taylors Creek, over which they transported their catches in carts. Mapmakers subsequently misread the name of the island and showed it as Carrot Island.

During the British invasion of Beaufort in 1782, the enemy forces camped one night on Carrot Island. A map produced during the American Revolution shows that Carrot Island was the only existing island among those now part of the preserve. Town Marsh, at that time called Island Marsh, was described as a “bunch of bushes.” Although the other islands in the present-day preserve were not yet exposed, the water in the area was extremely shallow.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, Town Marsh was known as Bird Shoal. By that time, it had grown from a mere spot of high ground just above the water line to an island nearly 0.4 mile long. Over the next thirty years, it doubled in length.

Dredging by the Corps of Engineers at the mouth of Taylors Creek in the early part of the twentieth century was responsible for the creation of the other islands in the complex. Continued dredging has built up the island chain to such an extent that it now affords protection for Beaufort during hurricanes.

When a developer announced plans to build resort homes on Carrot Island in 1977, Carteret County residents, civic groups, and environmental groups expressed alarm. To thwart the development plans, the North Carolina Nature Conservancy acquired 474 acres on Carrot Island. By 1985, the state of North Carolina had purchased the entire complex of islands.

The sanctuary can be reached only by boat. Local boating concessions and special boat trips sponsored by the North Carolina Maritime Museum provide transportation to the island during the summer season. Pleasure boaters are permitted to land their craft, but Carrot Island has few safe, sandy landing spots.

Once on the islands, visitors are surrounded by an unspoiled environment of natural beauty and solitude. Recreational activities include primitive camping, swimming, shelling, hiking, bird-watching, fishing, and clamming.

Ecologically, the sanctuary presents a diverse habitat that would not have come about except for the dredging operation. Found within the island system are tidal flats, salt marshes, ocean beaches, sand dunes, spoil areas, shrub thickets, and maritime forests.

At least 161 species of birds have been observed in the sanctuary. Because of its location along the Atlantic flyway, the complex hosts many migratory birds.

Ten species of reptiles, including the endangered Atlantic loggerhead turtle, are represented.

Of the mammal species present in the sanctuary, the feral horses that roam Carrot Island are the most interesting. For decades, visitors to Beaufort have gazed across the waterfront to catch a glimpse of these horses as they graze on the plant growth on the island. These animals are believed to be the descendants of a half-dozen horses left on the island in the 1940s by an area physician who wanted to take advantage of the free pastureland there.

For many years, drinking water was piped from the mainland for the horses. After the pipe failed, the horses had to devise ways to find fresh water, as the island has no ponds, streams, or springs. Since that time, the horses have learned to dig holes to trap the rain runoff that collects between sand dunes. At times, the underground water supply becomes so limited that the animals go to the sand flats, where they can sip thin layers of rainwater lying atop tidal pools.

In 1982, the number of horses on the island peaked at sixty-eight. Concern surfaced in the spring of that year when some of the animals died of starvation, brought about by drought and overbreeding. Attempts by Beaufort residents and state officials to feed the starving horses by boating hay to the island failed to solve the problem. Some observers watched helplessly as the dying horses fell. After falling, the animals struggled to get back on their feet. Ruts as deep as one foot were found around the legs of the fallen animals, evidence of their attempts to stand and defeat death.

Responding to the terrible plight of the horses, the state decided to cull the herd. In October 1988, the number of horses was reduced from fifty-two to fifteen during a state-sponsored roundup. Professional rodeo riders were brought to the island to rope the older, less healthy horses. After the roundup, the captured horses were transported to Beaufort, where they were subsequently adopted by animal lovers from many parts of the state.

Despite the claims of marine ecologists that the continued presence of the horses on the island will cause environmental damage, the state intends to maintain a manageable herd there.

Before returning to the parking lot, walk across Front Street to see two historic buildings in the downtown area.

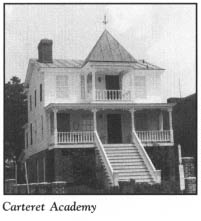

Located at 505 Front, the old Carteret Academy seems a bit out of place in the heart of the commercial district. This unusual three-story house served as a school for girls from the Outer Banks in the nineteenth century. Constructed in 1854, it is one of only two houses in Beaufort with an English basement.

Located just around the corner in the first block of Craven Street, the Norcum House, at 128 Craven, is one of a number of houses used by Federal forces during the Civil War occupation of the town. This large, two-story structure, built around 1850 from cypress lumber shipped from Plymouth, served as an army office building.

Return to the parking lot and drive east on Front Street. This scenic waterfront drive provides an excellent opportunity to view the horses on Carrot Island.

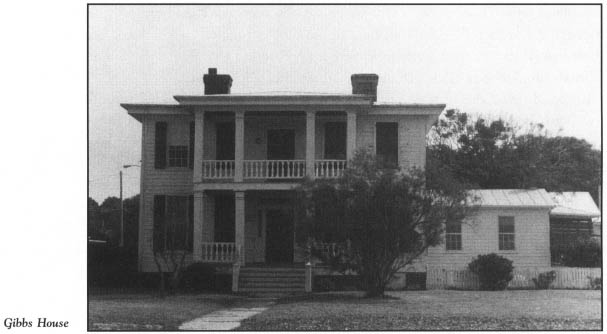

Located near the eastern end of Front Street, the Gibbs House, at 903 Front, is one of the most soundly built homes in Beaufort. It was constructed in 1850 of cypress lumber transported by sailboat from Hyde County. Six layers of wooden shakes were used to cover the hip roof. At one time, the structure housed the first United States Marine Laboratory on the Atlantic coast.

Of special interest is the brick-topped granite wall in the front and side yards, constructed in the early part of the twentieth century. This wall was designed to prevent waves from washing under the porch in the days before Front Street was filled in, when the water line in Beaufort was higher than it is at present.

Continue east on Front Street. Two blocks from the Gibbs House, turn left, or north, onto Fulford Street. Hammock Lane, an alleyway on the eastern side of Fulford, is the site of the most mysterious house in Beaufort.

No one knows for sure when or for whom the Hammock House was built. However, it is widely considered the oldest surviving house in Beaufort. Nestled in a grove of live oak, cedar, and yaupon on the highest hill in town, it has served as a guidepost for mariners since the early eighteenth century. On a 1738 chart of the North Carolina coast, the house appears as “The Hammock House.” Most likely, this ancient, two-story white house is the oldest man-made landmark used by seafarers on the North Carolina coast.

Estimates of the date of construction range from 1700 to 1735. Sills supporting the house are reported to be stamped with the year 1700. Its foundation is made of ballast stones. Before Front Street was filled in, the waters of Taylors Creek beat against the base of the twelve-foot hill on which the house stands.

Most of the seven-inch heart-of-pine boards used to cover the exterior of the house remain intact. Of the eight columns supporting the double front porches, seven are original. Nails, hand-forged on an anvil, are evident.

For many years, the Hammock House has been shrouded in mystery. Numerous eerie legends and tales about its owners and the goings-on there have evolved over the course of its long history.

The most fascinating of the stories are those involving Blackbeard. There is some belief in Beaufort that the infamous pirate built the house from plans he obtained in the Bahamas. Be that as it may, there is evidence that Blackbeard did call at the house on a number of occasions, particularly during his visits to Core Sound in 1718. He is said to have brought one of his wives to the house, leaving her to be executed after he went to sea again. Following the murder, her body was allegedly buried under nearby live oaks. Some Beaufort residents claim that on nights when the moon is full, her screaming ghost can be observed searching for her pirate husband.

Some members of Blackbeard’s crew were reportedly left at the house when the pirate sailed toward his fateful encounter with Lieutenant Robert Maynard at Ocracoke. After Blackbeard was killed by Maynard and his men, the stranded pirates decided to make Beaufort their home, becoming law-abiding citizens.

A sea captain and his wife occupied the house during the Civil War. During the early stages of the conflict, Confederate troops camped on the grounds. While the captain was away at sea, his wife grew increasingly concerned about living alone. To alleviate her fears, she invited a group of her friends to stay in the house. She took a lover as well.

One night, the captain returned to Beaufort unannounced. With his vessel anchored in the harbor, he made his way ashore in a landing craft and walked up the hill to the house, where a wild party was taking place.

The captain sneaked inside and confronted his wife’s lover. A struggle ensued. After chasing his wife’s paramour up the attic stairs, the irate husband killed him. Bloodstains from the struggle are said to be visible on the attic floor to this day.

Because of the many weird tales surrounding the Hammock House, some Beaufort parents will not allow their children to play nearby.

After 1 block on Fulford Street, turn west onto Ann Street. Follow Ann Street for 2 blocks, then turn north on Live Oak Street.

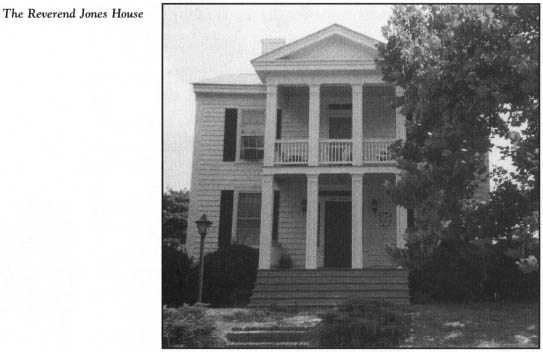

Located at the northwestern corner of the intersection of Live Oak and Broad streets, the Reverend Jones House served as a Union hospital during the Civil War. This splendid cypress-covered house was built in 1840. The first telephone in Beaufort had to be installed on a post in the yard of this house, since Mrs. Jones was too afraid of the new contraption to have it indoors.

Continue 1 block north. The tour ends here, where Live Oak Street joins U.S. 70.