This tour begins at the junction of U.S. 70 and N.C. 24 near the western limits of Morehead City. Proceed east 0.5 mile on U.S. 70 to the K-mart shopping center, on the southern side of the highway.

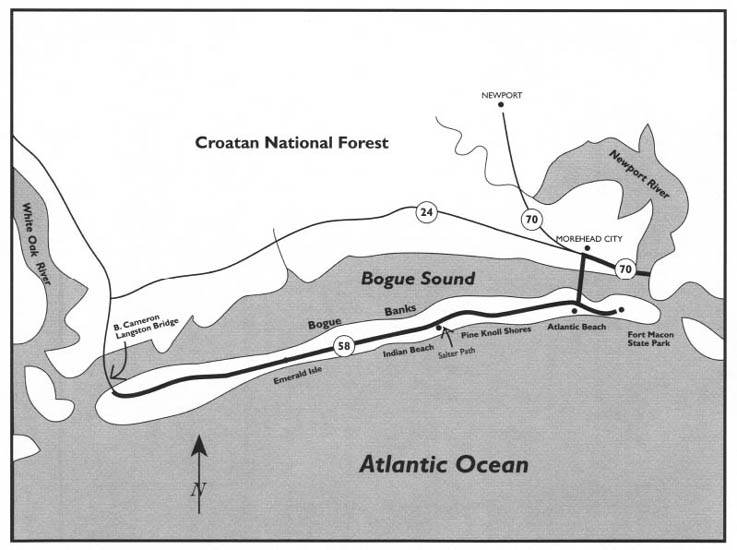

This tour begins in the historic port of Morehead City and travels across the Newport River to Radio and Pivers islands. It then crosses Bogue Sound to Bogue Banks, where it visits Fort Macon State Park, Atlantic Beach, Pine Knoll Shores, Indian Beach, Salter Path, and Emerald Isle.

Among the highlights of the tour are the North Carolina State Port at Morehead City, the Morehead City waterfront, the story of Old Quawk, historic Fort Macon, Theodore Roosevelt State Natural Area, and the North Carolina Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores.

Total mileage: approximately 42 miles.

On this site, a dog-racing track, the Hollywood Kennel Club, successfully operated from 1948 to 1953. An elaborate racing facility complete with grandstands and a press box attracted large crowds on summer evenings. The Miss North Carolina Pageant was once held at the track. When the state legislature made gambling at the track illegal in 1953, it was closed and abandoned. The track was torn down in 1970.

Drive 1.5 miles east on U.S. 70, which takes the name of Arendell Street on its run through Morehead City.

For almost two hundred years, the sun, the sand, and the moderate climate of Carteret County have made the place a favorite resort area for North Carolinians. Over the past several decades, Morehead City and Beaufort, the twin sound-side towns of mainland Carteret, and Bogue Banks, the barrier island lying just across Bogue Sound, have been collectively billed as “the Crystal Coast” by the local tourism industry.

Turn south off U.S. 70 onto Wallace Street at the sign for the Crystal Coast Civic Center. Located at 100 Wallace Street, the Carteret County Museum of History is based in a 1907-vintage frame building which once housed the school for Camp Glenn, a large World War I military encampment. A state historical marker on U.S. 70 describes the camp.

Owned and operated by the Carteret County Historical Society, the Carteret County Museum of History features exhibits dedicated to the study and preservation of local history. Among the displays are old photographs, artwork, seashells, Indian artifacts, quilts, and antique farm implements, furniture, and kitchen utensils. A research library containing materials on local history is available for visitors.

Located adjacent to the museum, the civic center is a modern thousand-seat facility owned and operated by Carteret County. Its outdoor plaza provides an outstanding panorama of Bogue Sound and Bogue Banks.

Several marine-research facilities are based in and around Morehead City. One of the most important is the Institute of Marine Sciences, located on the waterfront near the museum and the civic center. This facility is the product of a 1944 project designed to develop a fisheries institute for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Following World War II, biologists began their work in former naval facilities on the sound shore. The existing building was constructed in 1968. Through its programs of research and instruction, the institute serves the University of North Carolina and other universities, as well as state agencies.

Return to Arendell Street and proceed east. Located on the southern side of the highway just after it widens for the railroad median, the Crystal Coast Visitors Center and the adjacent picnic area and park offer a picturesque sound-side setting. The quiet picnic area shaded by live oaks is located on the former site of Carolina City, a nineteenth-century community that was subsequently swallowed up by Morehead City.

Unlike many coastal towns that developed without specific purpose or design, Morehead City was the product of extensive planning. It was the brainchild of John Motley Morehead, governor of North Carolina from 1841 to 1845. Prior to his service as the state’s chief executive, Morehead conceived the idea of developing a deepwater port in the Beaufort area. He envisioned a railroad linking the port to the Piedmont and cities on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

Upon completion of his term as governor, Morehead began to survey the Carteret coast for a desirable location for his port town. After much consideration, he concluded that the ideal spot was Beaufort harbor. But the prohibitive cost of a railroad trestle over the Newport River, which runs between Beaufort and Morehead City, forced Morehead to look for a site west of Beaufort. He and his associate, Silas Webb, settled upon a six-hundred-acre site just across the river at Shepard’s Point, where they set about developing “a great commercial city.” In 1853, working under the name of Shepard’s Point Land Company, they purchased the tract for $2,133.33 from the Arendell family, the namesake of the modern thoroughfare.

While Morehead was acquiring Shepard’s Point, he was also busy championing plans for the construction of the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad from Goldsboro to the site of his proposed port. Having laid the groundwork for the railroad during his term as governor, Morehead shrewdly enlisted the support of the state and a coalition of counties, towns, businesses, and citizens to complete the project.

Laid out by Morehead in 1855, Carolina City was to be the terminus of the railroad. However, the town met an early demise in 1857, thanks in part to the boom enjoyed by a new neighbor.

At the time the railroad and port were nearing completion, Morehead decided to subdivide most of his Shepard’s Point holdings into 50-by-100-foot lots. This newly laid-out town was located just east of Carolina City.

Preliminary lot sales began in November 1857, and regular railroad service from Goldsboro began on January 1, 1858. Over the next few months, excursion trains hauled thousands of interested North Carolinians to the new development. An official three-day opening celebration in late April brought more than ten thousand visitors to the town which bears Governor Morehead’s name. In less than thirty days, every lot in the new town had been sold, earning Morehead $1 million in the process.

A post office was established at Morehead City on February 28, 1859. Prominent families from the rural areas of the county settled in the town, causing it to expand rapidly westward. Pier Number One, as the early port terminal was called, was a beehive of activity. Large shipments of rails were unloaded at the port for use in the construction of the railroad.

Continue east along Arendell Street. The railroad tracks that split the street are reminders of the great enterprise started by Morehead.

Two state historical markers on Arendell call attention to the role that the new town played during the Civil War.

One of them stands fifty yards north of what was the largest Confederate saltworks in Carteret County. In the early stages of the Civil War, the state sought to alleviate the scarcity of salt by extracting the badly needed commodity from seawater. Morehead City was chosen as the site of the first saltworks. In April 1862, when the Union army invaded the area, the salt-processing operation was well under way. It was seized by the invading forces and destroyed.

As the Federal forces began to implement their plans to capture Fort Macon on Bogue Banks, they established a large army camp near the old site of Carolina City. Prior to their arrival, the Confederate army had maintained a large encampment there, covering approximately 1 square mile.

The second historical marker on Arendell Street designates the site of the camp. After Fort Macon fell to Union bombardment, the Federals maintained a sizable force at the camp for the duration of the war.

As you drive through the commercial district of modern Morehead City, you will be hard-pressed to find evidence that the city predates the Civil War.

At 301 Arendell Street stands the Jefferson Hotel, built around 1946. Its predecessor, the famed Atlantic Hotel, towered above the sound at this spot for more than a half-century. Constructed in 1880, the massive three-story frame structure contained 233 rooms. Its architectural design was similar to the famous spas of Victorian America. Throngs of vacationers and distinguished persons enjoyed the hospitality of the grand hotel, which became one of the most popular resort hotels in the state. Its immense popularity helped make Morehead City the unofficial summer capital of North Carolina during the last decade of the nineteenth century. Railroad officials, keenly aware of the value of the hotel to the growing resort economy, purchased it for use as a promotion in rail travel. A fire on April 15, 1933, destroyed the structure. A state historical marker on Arendell Street chronicles the history of the Atlantic.

Located on the waterfront just east of the Jefferson are the facilities of the North Carolina State Port. Motorists get a spectacular vista of the port as they cross the elevated bridge over the Newport River on the eastern side of the complex. Guided tours of the 116-acre port are available to the public. Tour participants enjoy a closeup view of the massive cargo ships that call on Morehead City from ports all over the world. All tours must be scheduled in advance with the ports authority.

Although John Motley Morehead established port facilities on the waterfront in the nineteenth century, the terminal was abandoned in 1904 and soon fell into disrepair. In 1933, the state legislature resurrected the port with the creation of the Morehead City Port Commission. A grant from the Public Works Administration enabled port construction to begin on November 1, 1935. Shortly after completion of the facilities in August of the following year, the SS Warzaristan docked at the new terminal with a load of salt from Africa, thereby earning the distinction of being the first ship to unload cargo at the new port. The first ship to be loaded, the SS Fernwood, left Morehead City on April 16, 1937, filled with scrap iron and steel bound for Japan.

Unfortunately, Morehead City has never been able to successfully compete with the ports of neighboring states. While a controversy boils over the reasons for this, there is no dispute that the facility has geographic advantages over Norfolk, Wilmington, Charleston, and other Atlantic ports. It is located in a natural harbor connected to the ocean by a 3-mile-long channel. Nearby Cape Lookout provides shelter from the fierce storms of the Atlantic. In nautical terms, Morehead City is closer to the Panama Canal and both South America coasts than most major Atlantic ports, with the exception of the Florida ports. Because of Morehead City’s proximity to the Gulf Stream, port traffic is the beneficiary of a temperate climate. Unlike the better-known ports to the north, navigation into the Carteret County port is rarely affected by fog, ice, and snow.

Approximately 130 persons are employed locally by the ports authority. However, almost 1,000 workers from various agencies and companies are involved in the daily operations. Texasgulf, with its expansive facilities in Beaufort County, is one of the largest exporters. Nearly two million tons of phosphate are barged down the Intracoastal Waterway from the town of Aurora each year. Accordingly, Morehead City has become known as a port for bulk cargo. Coal and phosphate, stored in the huge bins located on the northern side of Arendell, are loaded onto waiting ships by conveyor belt. Scores of tank cars stretching from the port to the central business district are a common weekday sight on Arendell.

Its proximity to the Second Division of the United States Marine Corps, based at Camp Lejeune, has made Morehead City the port of embarkation and debarkation for the marines and equipment from that huge installation. Military activity was particularly hectic at the port in 1990–91 during the deployment of troops and war material for Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm.

Continue to the eastern end of the port facilities, where U.S. 70 makes its way across the Newport River Bridge. Not only does the tall span provide a bird’s-eye view of the port, but it also affords a panoramic glimpse of the Newport River and its extensive marsh islands. This wide, but shallow, river runs 23 miles from central Carteret County to its entry into Bogue Sound near the bridge.

Newport River Park is located at the eastern end of the bridge on the northern side of the U.S. 70 causeway linking Morehead City and Beaufort. Situated on a dredge-spoil site, this new river-access facility features sandy beaches, a pier, picnic facilities, and restrooms. Trails lead to fishing spots on the river, and boardwalks yield splendid views of the port facilities and the river.

Radio Island, created by the Corps of Engineers in 1936 with dredge spoil from the Morehead City channel, is located on the southern side of U.S. 70. Turn south off U.S. 70 onto S.R. 1175 to drive onto the island.

On maps, the 390-acre island, which measures 1.4 miles by 0.7 mile, has the appearance of a miniature South America. It was named by a local radio station, but some locals refer it to as Inlet Island.

Until the North Carolina State Ports Authority recently purchased most of the island, area residents and vacationers used Radio Island as a playground where four-wheel-drive and all-terrain vehicles buzzed over the undeveloped landscape while fishermen, sunbathers, and picnickers crowded its beaches.

A twelve-acre site on the island has now been leased to Carteret County as a day-use public-access area. Divers and marine researchers are attracted to a nearby rock jetty around which teems marine life. Radio Island offers the only walk-in dive beach in the state. Ship watchers are treated to unlimited views of oceangoing traffic from the nearby state port.

Return to U.S. 70 and continue east along the causeway to the entrance to Pivers Island. After 0.6 mile, turn south onto S.R. 1208.

Although Pivers Island is much smaller than neighboring Radio Island, it is the center of the growing marine-research industry in the Morehead City-Beaufort area. Its importance is exemplified by the fact that Carteret County currently boasts one of the largest concentrations of marine scientists in the world. Of the six area marine-research facilities, four are located on the island: the Duke University Marine Laboratory, facilities of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries, and the North Carolina State University Seafood Laboratory.

In 1988, the Duke University Marine Laboratory celebrated its fiftieth anniversary on Pivers Island. Located on an eleven-acre tract on the southern portion of the island, the Duke campus contains approximately twenty buildings. Its appearance is deceptive. The six cabin-style dormitories housing more than a hundred students resemble a summer camp, rather than a major research facility.

More than 120 employees work at the laboratory, recognized worldwide as an outstanding interdisciplinary research and teaching facility. In addition to the Duke marine-science program, the campus also houses the Marine Biomedical Center, the Duke University/University of North Carolina Consortium, and other public and private research projects.

Chief among the programs of the Duke University/University of North Carolina Consortium is the operation of the 135-foot coastal-zone research ship, R/V Cape Hatteras. Since 1982, the consortium, under an agreement with its owner, the National Science Foundation, has operated the large steel-hulled ship for scientific expeditions. It is at sea about 250 days every year on cruises and research trips from Nova Scotia to the Caribbean.

Return to U.S. 70 and retrace your route west to downtown Morehead City. It is 1.9 miles on U.S. 70 to Fourth Street. Turn south onto Fourth, which dead-ends on the water at Evans Street. Turn right on Evans and drive west for a block or so.

Of the jewels in Morehead City’s crown, the most precious is the scenic commercial waterfront located on Evans and Shepard streets between Fourth and Tenth streets. Visitors are favorably impressed by the attractive appearance of the waterfront business district, the direct result of a revitalization project inaugurated by the city in 1984. Streetlights and sidewalks of hexagonal stones where installed in a 3-block area. A new bulkhead replaced the old sea wall constructed along Harbor Channel in the early part of the twentieth century.

Park in one of the lots or one of the street spaces along Evans Street. You will be greeted by a picturesque row of fish markets, famous seafood restaurants, and shops offering nautical gifts, books, and crafts.

Though they are indeed competitors for the tourist dollar, the two historic restaurants on the Morehead City waterfront exist harmoniously as matching bookends. The Sanitary Fish Market and Restaurant and Captain Bill’s Restaurant, located within sight of each other on Evans Street, are firmly established as institutions on the North Carolina coast.

Tony’s, as The Sanitary is popularly known, is the older of the two. Although it has achieved a worldwide reputation for its seafood and is the largest seafood restaurant on the North Carolina coast, it evolved from humble beginnings. A news story in a local newspaper on February 16, 1938, announced the opening of a waterfront fish market by two enterprising Morehead City businessmen, Ted Garner and Tony Seamon. Thus began a partnership that lasted forty years until Garner’s death on January 1, 1978.

In the early years, Tony and Ted housed their restaurant in a building that rented for $5.50 per week. Total seating in the original facility was twenty—twelve at the counter and eight at the tables. Tony used his party boat to supply fresh seafood for the new business, enabling the restaurant to advertise that its menu selections “slept in the ocean last night.”

Almost overnight, the restaurant was a hit. Anxious patrons began to wait in line to enjoy Tony’s famous “Shore Dinner.” By 1942, the restaurant had become so popular that Tony gave up his boat to devote all of his time to the eating establishment. Finally, in 1949, the ever-growing need for more space resulted in the construction of a new building on the present site. Subsequent additions increased the seating capacity to 650.

When the first Morehead City-Beaufort bridge was completed in 1927, Jesse Lee “Tony” Seamon was the first person to cross it. Thirty-seven years later, he was the first to drive across the replacement bridge. Tony died in Morehead City on May 28, 1985, at the age of eighty-one. Although Ted Garner, Jr., purchased the restaurant in December 1979, Tony’s name remains synonymous with the landmark.

Located west of The Sanitary, Captain Bill’s Waterfront Restaurant began as the brainchild of Captain Bill Ballou. Prior to World War II, Ballou operated a restaurant on Arendell Street. In 1945, he converted a waterfront officers’ club into a restaurant and gave it the name it enjoys today.

At Ballou’s death in 1960, Thomas Wade and Ken Newsome purchased the restaurant. After Wade and his wife were killed in a boating accident in 1967, Newsome continued the operation alone for a number of years. Many North Carolinians became familiar with the Wade-Newsome partnership through a popular Pilot Life Insurance Company television commercial during the 1970s.

Visitors to the Morehead City waterfront are fascinated by the fleet of for-hire sportfishing boats docked between The Sanitary and Captain Bill’s. From the adjacent boardwalk, pedestrians can share in the joy of happy fishermen as their bounty from the sea is unloaded and weighed. In the late afternoon, as twilight draws near, blackboards appear on boats, detailing the availability of the craft for future fishing expeditions.

Of the festivals and special events that attract visitors to the Morehead City waterfront, the largest and most popular is the North Carolina Seafood Festival. Inaugurated in 1987, the three-day event is held each October to showcase the maritime culture of Carteret County. More than 150,000 people flock to the event annually to enjoy a variety of activities, including historic tours and reenactments, ship tours, music, and local storytelling.

One of most enduring legends of Morehead City involves an old salt who shipwrecked on the sand banks of Carteret County. Where the creature came from, no one could ever ascertain. Local beachcombers called him a South American Indian because of his strange voice and language. His ship veered off course from either South America or Arabia during one of the frequent nor’easters that plague the Outer Banks.

Once ashore, the irreligious, bad-tempered sailor chose to stay in Carteret County. He wore a long pigtail, common to seagoing men of his time, and spoke with a squawking voice that locals could only equate with the guttural sound emitted by the black-crowned night heron. This unusual bird was locally known as a “quawk,” and so it came to be that area fishermen referred to this odd fellow as “Old Quawk.”

On occasion, the citizens would fish with Old Quawk. They would always end up shaking their heads in disgust at the stranger’s foul mouth and bad temper.

One Sunday morning in mid-March, hurricane-force winds lashed the Carteret County coastline with torrential rains and heavy seas. The local fishermen realized that the storm would force them to stay in port. Nonetheless, Old Quawk was determined to fish on that blustery March day. Even though they did not particularly like him, the veteran seafarers urged him not to defy the forces of nature. Rather than heeding their pleas, Old Quawk cursed and shook his fist at the angry sky.

In the midst of the tempest, he put out to sea. A lone night heron took flight after the boat. As man and bird united their voices in an unusual harmony, they disappeared into the storm and became legend forevermore.

In recent years, Morehead City has gained international attention because of its annual Bald Headed Men’s Convention.

Since it was founded by local resident John Capps in 1973, the Bald Headed Men of America Club has held its annual convention in the appropriately named Morehead City. Each year, club members from all over the United States travel to Carteret County to enjoy activities dedicated to baldness. In past years, guest speakers have included the likes of nationally syndicated columnist Erma Bombeck. Convention entertainment varies from the “Bald as a Golf Ball” tee-off tournament to the “Most Kissable” and “Sexiest” bald head contests. New members of the Bald Hall of Fame are announced at the convention.

Return to your car and continue in your original direction on Evans Street. West of the commercial waterfront are a number of historically significant buildings. Located at the corner of Evans and Eighth streets, the Morehead City Municipal Building, constructed in 1928, is an excellent example of Florentine Renaissance architecture.

Still farther west, the mainland shore of Bogue Sound is lined with a fine ensemble of beautiful multistory frame houses dating to the first half of the twentieth century. These majestic structures are located along Shepard and Shackleford streets. Interspersed among them are some dwellings that were originally constructed on Core and Shackleford banks and were later moved to their present location. A few of these old “C’ae Banker” houses are identifiable.

From the Morehead City Municipal Building, drive 2 blocks west on Evans to its intersection with South Tenth Street. Located on South Tenth near the intersection is the James Lewis House, which was originally constructed at Wade’s Shore on Shackleford Banks. When that community was abandoned, the house was floated to Morehead City on a skiff. A second story was later added with lumber salvaged from a shipwreck. This house is marked with a plaque that identifies it as a “C’ae Banker” structure.

Continue 2 blocks west on Evans. The Abram Lewis House, located at 1205 Evans, was built on Shackleford Banks by its namesake, Thereafter, the home was dismantled, floated across the sound, and reassembled at its current site.

Turn south off Evans onto Twelfth Street and proceed 1 block to Shepard Street. Kilby Guthrie, a recipient of the Congressional Gold Medal for heroism as a member of the United States Lifesaving Service, built the house now located at 1200 Shepard Street. Originally located on Shackleford Banks, it was later floated across the sound.

Turn around and proceed 2 blocks north on Twelfth Street to the intersection with Arendell Street. Turn left, or west, and drive 11 blocks on Arendell to Twenty-third Street. Turn left, or south, onto Twenty-third, which becomes Atlantic Beach Road.

Almost immediately, the road begins to rise as it makes its way across the four-lane high-rise bridge that spans Bogue Sound and connects Morehead City with Bogue Banks. Completed at a cost of $8 million in April 1987, the bridge has alleviated the long lines of summertime traffic that resulted when the old drawbridge was raised.

On the other side of the bridge lies Bogue Banks, generally considered the southern terminus of the famed Outer Banks of North Carolina. A causeway lined with motels, restaurants, and other businesses ushers motorists onto the island, which, at 29 miles, is the longest island on the North Carolina coast south of Cape Lookout.

Atlantic Beach, the popular beach town on the eastern end of the island, is the granddaddy of the resorts on Bogue Banks. When compared to the venerable resorts of the North Carolina coast, such as Nags Head, Wrightsville Beach, and Carolina Beach, Bogue Banks is a newcomer. Yet over the past seventy years, the island has emerged among the most popular vacation destinations on the entire coast.

In Atlantic Beach, at the busiest intersection on Bogue Banks, the causeway junctions with N.C. 58, the only east-west road running the length of the island. Turn east onto N.C. 58 and drive 3.5 miles to the end of the island. En route, N.C. 58 gives way to S.R. 1190.

This drive displays the widespread private resort development that has engulfed much of Bogue Banks. Chief among the reasons for the immense popularity of the island is the beautiful ocean strand stretching almost 30 miles. Not only is the island one of the longest on the North Carolina coast, but it has perhaps the most development potential. Unlike the other sizable islands of the Outer Banks, very little land on Bogue Banks has been reserved for government, military, or public use.

Located at the terminus of S.R. 1190, Fort Macon State Park is an exception.

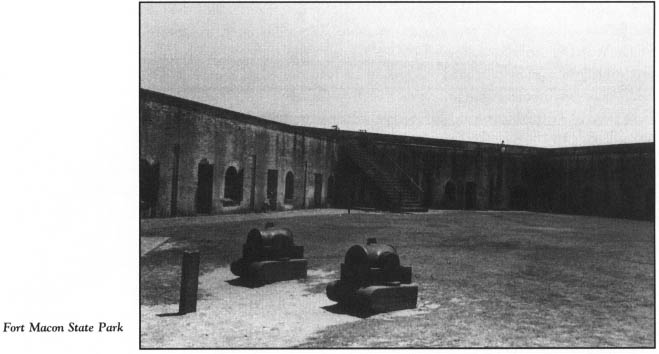

Each year, more than 1.25 million people visit Fort Macon State Park, making it the most-visited state park in North Carolina. At the park complex, patrons not only enjoy and learn about state history, but about the coastal environment as well For more than 150 years, Fort Macon has maintained a vigil over Beaufort Inlet, and thanks to the preservation efforts begun by the state more than a half-century ago, it appears much as it did when the first United States Army troops were stationed here in 1834.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the pentagon-shaped fortress is a well-preserved example of the nation’s early coastal defenses. Its magnificent architectural design is attributed to General Simon Bernard, a French military engineer who designed a number of forts on the East Coast. More than fifteen million bricks were laid by laborers working under the supervision of master masons.

When the fort was completed in December 1834, it was named in honor of Nathaniel Macon, a North Carolinian who became Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. He was subsequently elected to the Senate. A political favorite of Thomas Jefferson, Macon was dubbed “the last of the Romans” by Jefferson.

Not long after it was garrisoned, the fort began to be plagued by the kind of problems that had spelled the demise of its predecessor, Fort Hampton: erosion and storms. To remedy the problem, the United States Army sent one of its young West Point-trained engineers in the 1840s. While at Fort Macon, Captain Robert E. Lee designed and supervised the construction of a system of stone jetties still in use today.

In open defiance of President Lincoln’s request for North Carolina troops to suppress the rebellion of its Southern neighbors, Governor John W. Ellis ordered state troops to seize the coastal installations at Forts Macon, Caswell, and Johnston on April 15, 1861. Little did Ellis know that Fort Macon had been seized by state volunteers a day earlier. Over the next twelve months, Southern forces of about five hundred men garrisoned and fortified Fort Macon.

With Roanoke Island, New Bern, and much of the Outer Banks and the northern coastal plain under Federal control by mid-March 1862, the Union high command sensed that if the North Carolina coast fell, the entire Confederacy would be cut in half. Fort Macon was the logical next step in the quest for complete domination.

On March 22, 1862, General Ambrose Burnside dispatched General John G. Parke to initiate the preliminary work toward the capture of Fort Macon. Within a week, Union forces secured a beachhead on Bogue Banks. One month later, Lieutenant Colonel Moses J. White, the Mississippian who was in command of the fort, surrendered to General Burnside after the Confederates had weathered an eleven-hour battery from an overwhelming land and sea force.

For the duration of the war, Fort Macon remained under Union control. It was used as a penitentiary and a coaling station. Following the Civil War, the fort remained an active military installation, since there was no other such facility in either of the Carolinas at the time. Additional casemates were converted into prison cells. Visitors to the fort can still observe prison bars.

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the federal government changed its national defense policy. It developed a modern navy to command the seas, thereby eliminating the need for many of the existing coastal defense installations. One of the casualties of the new policy was Fort Macon. It was closed as a garrisoned military base on April 18, 1877.

During the Spanish-American War, the fort was briefly manned once again by the army. In 1903, the federal government officially closed Fort Macon. It remained closed during World War I. In 1923, defense officials deemed the fort obsolete and the property expendable. Two years later, the United States War Department conveyed the property to the state of North Carolina under the condition that Fort Macon be maintained as a state park.

Elaborate ceremonies highlighted by a speech by Governor J. C. B. Ehringhaus were held at Fort Macon on May 1, 1936, to celebrate the opening of the second park in the North Carolina’s state parks system. The opening was scheduled to coincide with the hundredth birthday of the fort.

Several weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the park was closed in order that the fort could once again be used for coastal defense. Throughout the war, it was manned by the 244th Division, Coast Artillery, of the United States Army. In June 1946, the last troops departed, and the site was released to the state.

A highly unusual accident took place at the fort during World War II. Troops stationed here found that their only heating system was fireplaces. In 1942, soldiers attempting to warm themselves used some unexploded Civil War shells as andirons. When they built a fire on the deadly ordnance, which they had mistaken as solid iron shot, the shells exploded, killing two and wounding others. So bizarre was the incident that it made “Ripley’s Believe It or Not,” a case of Civil War casualties occurring more than eighty years after the battle at Fort Macon was over.

The centerpiece of Fort Macon State Park is the ancient fort, considered by military historians and architectural experts to be one of the best-preserved forts in the nation. At first glance, knowledgeable visitors are impressed by its striking resemblance to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida.

The outer and inner walls are separated by a deep, twenty-five-foot-wide moat. Although now dry and covered with grass, the moat was at one time deeper than it is at present. It was filled with tidal water from nearby Bogue Sound.

More than twenty feet thick, the Covertway, as the outer walls are collectively called, is built of sand and masonry. It affords magnificent views of Beaufort Inlet, Shackleford Banks, Bogue Sound, Bogue Banks, and the Morehead City and Beaufort waterfronts. There are four rooms with cannon placements on the outer walls. Beneath these outer ramparts are dungeons, now filled with water.

On the northern side of the fort, a wooden walkway located at the site of the old drawbridge crosses the moat to the main entrance—the sally port. Directly through the sally port lies the half-acre parade ground. Surrounding the parade ground are the five-foot-thick inner walls. These walls, of beautiful brick construction, actually form the fort proper. Three handsome staircases, adorned with wrought-iron handrails crafted to resemble the originals, lead to the terreplein—the top platform.

Twenty-six casemates, or vaulted rooms, are situated around the parade grounds. A number of the casemates have been restored since 1977. One of the rooms was restored to represent the quarters of enlisted men, complete with bunk beds. Lieutenant Colonel Moses White’s room has been furnished with a bed, chairs, and a table constructed in the shop at the park. Swords, hats, uniforms, and other Civil War memorabilia are also on display. An audiovisual program detailing the unfortunate story of Lieutenant Colonel White is presented in the commanding officer’s quarters. White was plagued by epilepsy throughout much of his career. He died at the age of twenty-nine.

Although other casemates have not been restored, most are open to the public. Visitors are free to examine the masterful military engineering which went into the domed rooms, the delicately curved brick arches, and the vaulted stairways. Throughout the fort, you will marvel at the hundreds of bricks that were bent and shaped to fit the unique design of the arches, walls, and floors. Some of the most intricate and unusual brickwork of nineteenth-century America can be observed at the fort. It has been suggested that few modern architects could replicate the arches that have endured here for more than a century and a half.

Attendants on duty throughout the fort answer questions and provide information about the installation. Guided tours are conducted daily, and Civil War reenactments are held on the parade grounds on spring and summer weekends. A museum and a bookstore are located in the casemates.

Although the fort covers only eight acres, the park covers 398 acres. In addition to tours of the fort, a variety of activities is offered at the park. Nature-study programs and beach walks conducted by park rangers cover topics ranging from shells to brown pelicans.

Near the parking lot at the fort entrance, visitors can enjoy the Elliott Coues Nature Trail. Named for the army physician who was stationed at Fort Macon in 1869 and 1870, this easy 0.4-mile loop trail passes through dense shrub thickets to Beaufort Inlet. At the inlet, visitors can observe the jetties constructed by Robert E. Lee. Often found on the jetty rocks are invertebrates such as starfish and sea urchins.

The hiking trail passes near the site of the two military installations that preceded Fort Macon. In response to the Spanish attack on Beaufort in 1747, work began on Fort Dobbs on the eastern end of Bogue Banks in 1756. However, this fort was never completed. In 1808, construction began on Fort Hampton, a small masonry installation at a site three hundred yards east of the present fort. Almost as soon as it was completed, the fort fell prey to erosion.

West of Fort Macon and near the park entrance, a park road takes visitors to picnic grounds, a bathhouse and pavilion, and a public beach. From the bathhouse building, a boardwalk provides access to the beautiful Bogue Banks strand. Dolphins and whales can occasionally be observed in the ocean.

Located adjacent to the state park is the Fort Macon Coast Guard Station, the successor to the old Fort Macon Life Boat Station. This base serves as the command post for the Coast Guard units at Hobucken, Swansboro, Wrightsville Beach, and Oak Island. In November 1990, the Fort Macon installation achieved a historic milestone when Lieutenant Commander Cynthia A. Coogan was named its commander. She became the first woman to command a Coast Guard group in the two-hundred-year history of America’s smallest branch of military service.

Retrace your route to the intersection of N.C. 58 and the causeway in Atlantic Beach.

Although the eastern portion of the island—that lying between Fort Macon and this intersection—falls within the corporate limits of Atlantic Beach, it is referred to locally as Money Island Beach, a name that can be traced to the Civil War.

One of the vital elements of General Burnside’s plan to assault Fort Macon was the construction of rafts to float troops and artillery across Bogue Sound. In charge of the raft construction was a cunning Yankee sergeant. Once the crude vessels were built and loaded, the sergeant assembled his soldiers and announced, “Gentlemen, we are going on a very dangerous mission, and we have been instructed not to let anything of value fall into the hands of the enemy, so I want you to bring me all of your money and jewelry. We will bury it here on the banks of Bogue Sound. When the battle is over, we will return here and I will give you back your belongings.”

A big cedar tree on Bogue Banks was selected to mark the spot for the burial of the valuables. Each soldier watched intently as his property was carefully placed in a hole dug at the roots of the tree. Although the troops left a mark on the tree to identify it, they took care to leave no evidence of the excavation.

After the swift capture of Fort Macon, the troops whose belongings were buried on Bogue Banks were dispatched to other battlefields, save one. Somehow, the crafty sergeant was able to remain in Beaufort for the remainder of the war. Once the hostilities ceased and he was satisfied that all the others had forgotten the cache, he made his move. He engaged a local fisherman to row him across the sound to retrieve the hidden riches. For his services, the fisherman was promised half the booty.

As fate would have it, about halfway across the sound, the fisherman noticed that the sergeant had taken sick. A closer examination revealed that he was burning up with fever. Immediately, the fisherman maneuvered the boat back toward the mainland. By the time they reached the doctor’s office in Beaufort, the sergeant had lapsed into unconsciousness. The physician diagnosed the illness as typhoid fever. Without ever revealing the location of the treasure, the sergeant died. Since his death, many cedar trees on Bogue Banks have been dug up, but no one has ever found the valuables hidden long ago.

At the busy intersection in Atlantic Beach, the name of the causeway changes from Morehead Avenue to Central Avenue. Drive south on Central Avenue to its terminus at Atlantic Avenue, the street that runs parallel to the strand, and park your car. Parking is available on East and West drives, which combine with Central Avenue to form a Y in the heart of the old resort. Amusement parks and beach clubs have come and gone in this area since the 1920s.

A two-story frame hotel was constructed in the fledgling resort in 1923. Prior to that time, this stretch of strand attracted day visitors from Morehead City and other mainland points. Once they were boated across the sound, early beach enthusiasts found little more than a crude bathhouse to accommodate them.

Things began to improve in 1928 with the construction of the first bridge to Bogue Banks. Until 1938, when it was sold to the state, the bridge at Twenty-eighth Street was operated as a toll bridge. Completion of the Atlantic Beach Hotel in 1938 further propelled the resort toward becoming an important tourist destination. Until it was destroyed in 1965, the old hotel stood as a beach landmark.

By World War II, Atlantic Beach, incorporated in 1937, was enjoying widespread popularity. Spread along the strand were numerous cottages and amusement facilities, including a bowling alley and a large pavilion. Following the war, the island began luring so many visitors that the state was forced in 1953 to build a new bridge at Twenty-fourth Street to replace the original structure.

From the parking area, walk to the boardwalk running along the strand. No longer a boardwalk in the true sense of the word, this concrete walkway provides an opportunity to see the numerous half-century-old beach houses that grace the Atlantic Beach oceanfront. To the west, down the strand, the towering hotels and condominiums of Pine Knoll Shores loom on the horizon. Beachcombers will also notice the long sea wall on the strand, evidence of the relentless, costly battle that the town continues to wage against erosion.

Return to the parking area and drive back to the intersection of N.C. 58 and Central. Proceed west on N.C. 58.

Although it was little more than a sandy lane, the first road from Atlantic Beach to Salter Path, 9 miles to the west, was completed during the Depression. Earning $1.25 per day from the federal government, local residents used axes and brush knives to hack their way through the dense maritime forest of live oaks and yaupon. In the 1940s, the state assumed maintenance of the road, and in the process widened and improved it with a clay foundation. The road was not paved until the next decade.

Because of the almost uninterrupted development along N.C. 58, the boundaries of the five resort villages on Bogue Banks are often difficult for visitors to ascertain. Atlantic Beach gradually gives way to Pine Knoll Shores after 2.5 miles.

In appearance, Pine Knoll Shores presents a stark contrast to Atlantic Beach. Newer, fresher, and less densely developed, this resort community of more than a thousand permanent residents contains the most suitable land for development on the island. Remnants of maritime forests are still in evidence along the highway.

A state historical marker on N.C. 58 in Pine Knoll Shores honors famed Florentine navigator Giovanni da Verrazano, who first explored Bogue Banks in 1524.

There remains, however, some dispute as to the origin of the island’s name. Most historians believe that it was named for Joseph Bogue, who settled in the area in the early eighteenth century. On the other hand, some writers have noted that “bogue” is a Choctaw Indian reference to a stream or water passage. Along the coast, a bogue is taken to mean a swampy area. There is also some evidence that the word comes from a Spanish term denoting movement to the leeward. Lending credence to the Spanish origin are the incontrovertible facts that Bogue is one of the oldest place names on the North Carolina coast and that Spaniards frequently visited, raided, and were shipwrecked on the Outer Banks in the sixteenth, seventeenth, and early eighteenth centuries.

Regardless of the source of its name, the island was known as Bogue Banks by the eighteenth century, as evidenced in the Moseley map of 1733.

Located on the ocean side of the highway approximately 6 miles from Atlantic Beach, the Iron Steamer Fishing Pier in Pine Knoll Shores marks the site of the wreck of the Confederate blockade runner Prevensey, a side-wheel steamer. A Federal warship ran the five-hundred-ton iron ship aground here in 1864.

Park in the pier lot and walk out onto the east wing of the pier. The Prevensey’s rusting axle and boiler are visible below the surface. Portions of the ship can be seen from the strand at low tide.

Near the pier, turn north off N.C. 58 onto S.R. 1201 for a drive of 0.4 mile to the Theodore Roosevelt State Natural Area and the North Carolina Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores.

Located on a 297-acre sound-side site, the Theodore Roosevelt State Natural Area preserves one of the few areas of undisturbed vegetation and wildlife habitats on Bogue Banks. This unique remnant of maritime forest was given to the state by the Roosevelt family. Upon its acquisition, it became the state’s second officially designated natural area. As such, the site has been subject only to such development as is necessary to preserve the area and to provide interpretive programs.

Although few visitor facilities are provided, visitors may hike through the natural area on the Alice G. Hoffman Nature Trail. This 0.25-mile route offers an excellent overview of the complicated ecosystem of salt marsh, inland freshwater slough, and ancient dunes now stabilized by maritime and shrub-forest communities. At the East Pond Overlook and at other lagoons in the natural area, alligators are commonly observed.

The trailhead for the Alice G. Hoffman Nature Trail is located adjacent to the North Carolina Aquarium at Pine Knoll Shores. Like its sister facilities at Manteo and Fort Fisher, this marine center serves the public and scientific communities. Visitors enjoy attractive displays and artifacts relating to the natural and human history of the North Carolina coast. Special “hands-on” tours on board the trawler First Mate are frequently sponsored by the aquarium.

Return to N.C. 58 and continue west. Approximately 2 miles from the turnoff to the state natural area and the aquarium, you will leave Pine Knoll Shores and enter the eastern portion of Indian Beach. Numerous high-rise condominiums have changed the landscape of this part of the island.

Salter Path, located 0.7 mile farther west, presents a sharp contrast to the dense development of the two sections of Indian Beach to the east and west. As N.C. 58 winds its way through the picturesque village, you will pass by white frame dwellings that remain in the possession of the descendants of the original settlers.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, fishermen took up permanent residence on Bogue Banks, fleeing their homes on Core and Shackleford banks. Few, if any, bothered to acquire title to the land on which they settled. By the turn of the century, two settlements started by these squatters had grown into the distinct communities of Salter Path and Rice Path. The word path was once part of the vernacular of residents of the southern Outer Banks. It refers to a locality on the island used by people from the mainland for specific activities.

Perhaps they did not bother to obtain deeds to their property because it was considered relatively worthless. Or perhaps they simply could not afford to pay the meager amounts that would have constituted the purchase price. For whatever reason, almost all of the original settlers of the village of Salter Path were squatters.

Although some of the early residents of the village claimed that Salter Path was named for the Salter family, who supposedly lived on the island in the nineteenth century, the actual community dates from 1900. A more likely explanation is that the name was adopted from the dunes-to-saltwater patch of ground on which the settlement grew.

Few, if any, of the early residents of the village bothered to ask the owner of the land for permission to live there. John A. Royal, a native of Carteret County and a Boston resident, owned not only the middle portion of the island, but the eastern portion to Atlantic Beach and the entire western half as well. However, Royal did little to interfere with the lifestyle of the squatters.

In 1917, Royal sold the stretch of property from Salter Path to Atlantic Beach. The squatters were quick to realize that the new owner might not be as lenient as Royal. No sooner had Mrs. Alice Hoffman acquired the property than she announced that she would no longer allow residents to settle where they pleased or to rummage about collecting firewood. Villagers were also told to stop their cattle from roaming.

A bitter controversy ensued. Mrs. Hoffman, a socialite from New York and Paris, ensconced herself at her fine home on Bogue Sound. Finally, irate squatters proceeded en masse to Mrs. Hoffman’s estate, where they openly displayed their hostility to her policies. For several days, the protestors marched around her house and fired their guns.

Mrs. Hoffman would not bow to the pressure of the villagers. Determined to bring the controversy to a conclusion, she chose to have the matter litigated in Carteret County Superior Court. At one point, she said, “I’d rather go to court than to the theater.”

A judgment rendered by the court in 1953 ended the dispute. Under its terms, the thirty-five squatters were not evicted, but their settlement was restricted to eighty-four acres. A further judicial restriction required that every house had to be handed down from generation to generation and occupied by the descendants of the original owner. Otherwise, the property would revert immediately to Mrs. Hoffman or her estate.

Until her death on March 15, 1953, at the age of ninety-three, Mrs. Hoffman spent much of her time at her estate on Oakleaf Drive in Pine Knoll Shores. Approximately three hundred people were living at Salter Path at the time of her death. Her holdings of more than 2,000 acres were inherited by the children of Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. Subsequently, the Roosevelt family sold or gave away all but 175 acres.

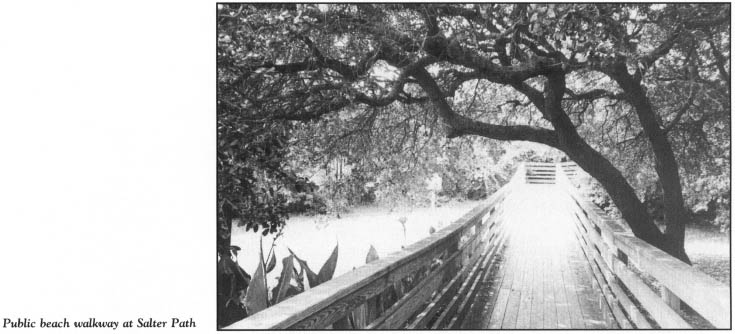

In the heart of Salter Path alongside N.C. 58, Carteret County has developed a picturesque twenty-two-acre site providing access to the strand. From the parking area enclosed by a picket fence, a boardwalk leads through a majestic maritime forest to an undisturbed dune field and the public beach. Picnic facilities, restrooms, and a bathhouse are provided.

Continue west on N.C. 58. The western portion of Indian Beach presents a different appearance from the village of the same name on the eastern side of Salter Path. Its landscape is punctuated by a high density of mobile homes. For many years, it has been a favorite spot for fishermen.

At the western limit of Indian Beach, the island narrows drastically as U.S. 58 carries motorists on a 9.5-mile drive through the resort town of Emerald Isle. A permanent population of approximately twenty-five hundred is spread throughout the town, which extends down the western third of Bogue Banks. Property development here has been characterized by single-family cottages, versus the condominiums and hotels in the Atlantic Beach-Pine Knoll Shores area.

As you drive by the sand dunes and beach houses lining the highway, there is little to distinguish one mile from another in Emerald Isle. Had the early-twentieth-century dreams of one man come true, Emerald Isle might have become one of the premier resorts of the entire Atlantic coast.

Henry K. Fort, a wealthy industrialist from Philadelphia, purchased a 12.5-mile stretch of Bogue Banks from Salter Path to Bogue Inlet in 1918. He acquired an additional tract of 496 acres on the mainland at present-day Cape Carteret six years later. Both parcels were purchased from John Royal.

Fort, a pencil-manufacturing magnate, became interested in the island because of its abundance of cedar trees. However, he soon discovered that the cedar could not be harvested and shipped economically. Soon after his acquisition of the mainland parcel, he dispatched a crew of engineers from New Jersey to Bogue Banks. For several months, the team surveyed Fort’s holdings and reduced its findings to maps.

Once the engineers and architects completed their work, an artist painted Fort’s conception of a resort comparable to Atlantic City, New Jersey. It depicted streets, summer homes, businesses, fishing piers, and amusement centers. On the mainland portion of the Fort holdings, plans called for year-round homes, businesses, and recreation areas.

Essential to the realization of Fort’s dream was the construction of a bridge at the western end of the island. His efforts to persuade state and county officials to provide assistance with the bridge were unsuccessful. Determined to complete his project, Fort proceeded with his plans until the grand dream became one of the many casualties of the Depression.

Fort died in 1943, leaving his vast holdings to his daughter. Ultimately, she sold nearly 10 miles of the land to a group of seven men from the North Carolina communities of Smithfield and Red Springs. Once the deal was consummated, the seven individuals divided the land into two-thousand-foot oceanfront sections. It was on this property that the resort of Emerald Isle began to take shape in the 1950s.

The town of Emerald Isle was incorporated in 1957. Its growth was spurred by the establishment of a state-operated toll-free ferry from the western end of the island to the mainland.

Once you have toured Emerald Isle, drive across the B. Cameron Langston Bridge over Bogue Sound. Completed in 1971, this high-rise span affords a magnificent view of the shallow sound and its green marsh islands. To the west lies Bogue Inlet, the southern boundary of Bogue Banks. Only three inlets along the entire North Carolina coast are known to have been open continuously since 1585. Two of the three—Bogue and Beaufort inlets—serve as boundaries for Bogue Banks.

The tour ends on the mainland at the far end of the B. Cameron Langston Bridge.