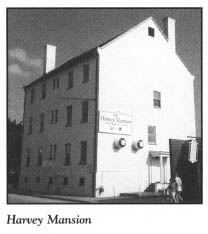

This tour begins at the intersection of S.R. 1004 (Madam Moore’s Lane) and U.S. 70 Business just across the Trent River from New Bern. Near the intersection, two state historical markers call attention to Abner Nash, Richard Dobbs Spaight, and Richard Dobbs Spaight, Jr., three North Carolina governors who are buried nearby. Another marker acquaints visitors with the Battle of New Bern on March 14, 1862.

This tour combines a driving tour and a walking tour of historic New Bern, one of coastal North Carolina’s great treasures.

Among the highlights of the tour are the New Bern waterfront, New Bern City Hall, the story of Caleb “Doc” Bradham, Christ Episcopal Church, the magnificent Tryon Palace restoration, the John Wright Stanly House, the New Bern Firemen’s Museum, the story of Fred the horse, First Presbyterian Church, the New Bern Academy Museum, and New Bern National Cemetery.

Total mileage: approximately 11 miles.

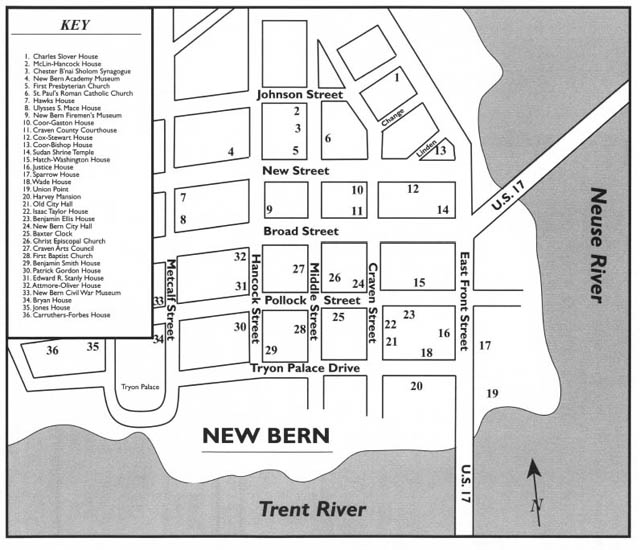

To visit the Spaight Family Cemetery, proceed 2.5 miles south on S.R. 1004.

Among the graves within the brick-wall-enclosed cemetery are those of Governor Richard Dobbs Spaight (1758–1802), a signer of the United States Constitution, Governor Richard Dobbs Spaight, Jr. (1796–1850), and Mary Dorothy Vail Moore (1735–1775). These graves and others of the Spaight family are located on property that once was part of Chermont, a 2,500-acre plantation along the Trent River. An elegant mansion built by Mary Moore graced the plantation.

Moore’s daughter was the wife of Richard Dobbs Spaight, whose tomb was desecrated by invading Union forces when they burned the mansion in 1862. The marauders took Spaight’s skeleton from its resting place and displayed his skull on a gatepost. The body of a fallen Union soldier was placed in Spaight’s metal coffin for shipment north.

Return to the intersection of S.R. 1004 and U.S. 70 Business. Turn north on U.S. 70 Business and proceed across the bridge spanning the Trent River.

Visitors approaching New Bern on any of the several bridges leading into town are treated to one of the most beautiful panoramas in all of coastal North Carolina. The broad, scenic rivers encircling the town, the church spires towering above centuries-old structures, and a living display of North Carolina’s proud past converge to welcome visitors to a modern city that retains much of the charm of a bygone era.

Prominently situated on a peninsula formed by the confluence of the Neuse and Trent rivers, the historic city has an atmosphere matched by few others on the Atlantic coast. Bathed in antiquity, yet clothed with the amenities of the modern world, North Carolina’s second-oldest incorporated town maintains a graceful and exquisite blend of old and new. Now almost three centuries old, this Craven County town, born of the dreams of Baron Christophe DeGraffenried and John Lawson, has grown into a vibrant commercial center whose citizens have done a commendable job in preserving its heritage.

Without question, the best place to begin a tour of New Bern is on its picturesque waterfront. Union Point, located at the northern end of the bridge over the Trent River, is a small spit of land marking the juncture of the two great rivers. After this historic ground was used for decades as a dumping ground for trash, a local woman’s club, in cooperation with the city, developed it into a small municipal park. Located within the park is the Woman’s Club Building, constructed in 1932 from concrete curbing that had been dumped at Union Point. Equipped with picnic facilities and a boat landing, Union Point Park is located on U.S. 70 (East Front Street) at Tryon Palace Drive.

Park at Union Point Park.

Thanks to the chronicles of John Lawson, North Carolina’s first resident historian, many details of the founding of New Bern survive. When the intrepid Lawson first caught sight of Union Point in the early eighteenth century, he was not only awed by its wild beauty, but also cognizant of its strategic value. Its two rivers and their tributaries, navigable far into the interior, provided access to the Atlantic through Ocracoke Inlet. Long before Lawson’s arrival, the future site of New Bern had been a favored spot among area Indians. They called it Chattawka, meaning “where fish are taken.”

Somehow, Lawson was able to persuade the Indians to part with some of their prime real estate. He purchased a thousand acres and constructed a cabin approximately 0.25 mile from the nearest Indian village. Impressed by the amicable nature of the Indians, Lawson sent exciting accounts of the Neuse area and its fertile, inexpensive lands back to Europe.

By 1709, he returned to London to oversee publication of his book, A New Voyage to Carolina. While in Europe, Lawson extolled the virtues of his New World paradise to three men from Bern, Switzerland. George Ritter was interested in settling a group of paupers and religious dissenters in the American colonies, while Christophe DeGraffenried and Franz Ludwig Michel were looking to obtain mining rights to the vast mineral resources lying just across the ocean.

Lawson was so persuasive that the three men successfully negotiated with the English Crown and the Lords Proprietors to obtain land in the New World. As a result, Ritter and Company acquired 18,750 acres along the Neuse and Trent rivers. DeGraffenried, the head of the company, dispatched an advance team of Lawson and Christopher Gale to select a site for the first settlement.

An attempt to settle the site in 1710 with 650 German Protestants expelled from Baden and Bavaria failed miserably. Land disputes with the neighboring Tuscaroras ensued. Finally, after these initial setbacks, DeGraffenried was able to concentrate his energies toward establishing the town he had envisioned. At the request of DeGraffenried, Lawson laid out the town on the point between the two rivers.

Lawson’s engineering genius was evident in the main streets. They were laid out in the form of a cross, one running from river to river and the other running northwest from the confluence of the two rivers. Although this design had religious implications, practical considerations were paramount in Lawson’s scheme. Ramparts constructed along the transverse road provided a measure of defense against Indians.

In honor of the capital of his native land, DeGraffenried named his town Bern-on-the-Neuse. Among the early residents, the name quickly became New Bern. Almost overnight, New Bern achieved a prominence which rivaled that of Bath and Edenton.

Unfortunately, several tragic events in 1711 seemed to lend credence to the belief that DeGraffenried’s town was ill-fated.

In September, Lawson cajoled DeGraffenried into making a canoe trip up the Neuse. A few days into the trip, the expedition fell into the hands of a war party of Tuscaroras. In a desperate plea for his life, DeGraffenried threatened the Indians with reprisals by the English Crown, promised them favors and services, and shifted all the blame for the Indians’ woes onto Lawson. At the last moment, his life was spared, but Lawson was not so fortunate. Ironically, he died a horrible death by a style of torture which he had witnessed and written about earlier: “Others split the pitch pine into splinters and stick them into the prisoner’s body yet alive. Thus they light them, which burn like so many torches, and in this manner they make him dance round a great fire, every one buffeting and deriding him til he expires, when every one strives to get a bone or some relic of this unfortunate captive.”

At dawn on the day following Lawson’s demise, DeGraffenried was told of a mighty Tuscarora assault which was about to be carried out on white settlers. He was detained as a prisoner and forced to sit by helplessly as the entire area was ravaged. During the first wave of the mayhem, New Bern was spared. However, the gruesome bloodbath was to plague the entire region for the next two years.

A financially ruined, disgusted DeGraffenried mortgaged his holdings to Thomas Pollock, a wealthy planter and acting governor of North Carolina, and moved to Williamsburg, Virginia, where he stayed with Governor Alexander Spotswood for a brief time. Finally, in 1714, DeGraffenried sailed with a group of the surviving Swiss settlers for Europe, never again to return to America.

In the meantime, the Tuscaroras were soundly defeated in March 1713 at Snow Hill, approximately 45 miles to the west, by a band of Indian fighters, white settlers, and friendly Indians. Following the defeat, the Tuscaroras moved from North Carolina to upper New York, where they joined the Five Nations. There, they gave their new land the name of their North Carolina home. Over time, Chattawka became the now-famous Chautauqua, New York.

New Bern witnessed its rebirth around 1720 under the tutelage of Cullen Pollock, the son and heir of Thomas Pollock. He worked diligently to promote the town, and due in large part to his efforts, the settlement by the rivers emerged as an important seaport and seat of government. In 1723, the town was incorporated and made the seat of Craven County, a political subdivision created in 1705 and named in honor of William, earl of Craven, the longest-lived of the eight Lords Proprietors.

As the North Carolina colony grew, choice land on the coast became scarce. Consequently, settlement spread inland and to the south. These new settlement patterns worked to the benefit of New Bern. Suddenly, the town was at the center of the state, rather than on the fringes of the frontier. By 1732, roads connected the town with the Albemarle region to the north and Charleston, South Carolina, to the south. New Bern’s central location and increasing prominence within the colony led the colonial assembly to convene here in 1737.

After years of setbacks and ill fortune, DeGraffenried’s dream was coming true. Yet events were soon to occur that would forever end his vision of a permanent German-Swiss outpost in America.

None of the original European settlers at New Bern owned their land. Once the Pollock family called in the mortgages and took control of the settlements, few of the German-Swiss colonists had the means to purchase the land on which they lived. Most of them were forced from their original plots in 1749 and dispersed inland. English-speaking settlers rapidly replaced the last of the DeGraffenried colonists, thus sealing the destiny of New Bern as a British American town.

To view the city that John Lawson designed in 1710, proceed west from Union Point Park across East Front Street onto Tryon Palace Drive.

New Bern and Wilmington stand as the two ancient cities of significant size on the North Carolina coast that have taken important steps toward the preservation of their illustrious pasts. Throughout the twentieth century, New Bern has avoided the mistakes of other cities on the Atlantic coast that have, through demolition and urban renewal, deprived future generations of the enjoyment of historic structures. Due to the efforts of various associations and countless individuals, the city possesses a superb ensemble of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century buildings of not only state, but national, importance. More than two dozen of them are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

As soon as you enter Tryon Palace Drive, you will get a sample of the historic structures of the city.

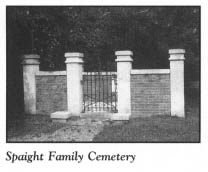

Constructed in 1843, the Wade House, located at 214 Tryon Palace, is a massive, three-story frame dwelling. When it was remodeled in the Second Empire style in the 1880s, the distinctive mansard roof was added.

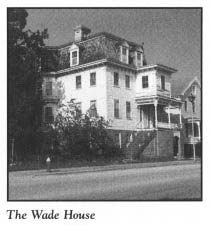

Nearby at 219 Tryon Palace stands the Harvey Mansion, a three-story Federal-style edifice erected in 1798 as a residence and office for John Harvey, a prosperous ship owner and merchant. Of particular interest is the elegant Federal woodwork in the interior, considered the finest in the city. Slated for demolition, the imposing building was saved by the New Bern Renewal Commission. It has been meticulously restored as a popular restaurant.

After 1 block on Tryon Palace Drive, turn right, or north, onto Craven Street.

Located on the eastern side of the street at 220–226 Craven, the old city hall exhibits a turn-of-the-century front that masks the original 1817 facade.

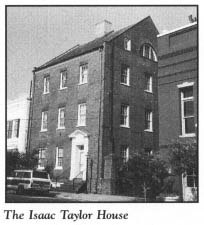

Adjacent to the old city hall, the Isaac Taylor House, at 228 Craven, is the oldest brick side-hall-plan townhouse in the city. Built in 1792 for Isaac Taylor, an affluent merchant, planter, and ship owner, the tall structure has three full stories and an attic above a full basement.

After 1 block on Craven Street, turn left, or west, onto Pollock Street. Park in the 300 block of Pollock in the heart of downtown New Bern. Much of the old city can best be explored on foot. Many of the important structures are located within an 8-block area surrounding the current tour stop. Each historic building is identified with a plaque and the Historic New Bern sign. This special area is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the New Bern Historic District.

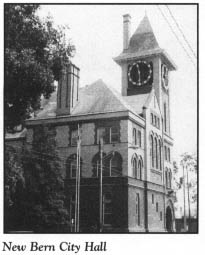

Walk east on Pollock to the intersection with Craven. Located on the northwestern corner of the intersection at 300 Pollock, New Bern City Hall is one of the most unusual buildings in the city. This striking Romanesque Revival three-story brick structure was constructed between 1895 and 1897 to house the United States Post Office, Courthouse, and Custom House. Its distinctive clock tower dominates the Pollock Street landscape. This illuminated, four-sided clock tower was added in 1910.

Since 1936, the property has served as the municipal building for the city of New Bern.

Cast-metal black bears, gifts from Bern, Switzerland, guard each entrance to the building. New Bern shares this symbol with it sister city in Europe. Inside the building hangs a framed bear banner, a gift from the Swiss ambassador to the United States in 1896. Visitors will notice the bear on signs, flags, and plaques throughout the city.

A larger-than-life bust of Christophe DeGraffenried was dedicated on the lawn of city hall on April 9, 1989. Representatives from the Swiss and German governments and a descendent of DeGraffenried were in attendance when the monument was unveiled.

Proceed east on Pollock Street. Constructed in 1845 as a brick Federal-style townhouse, the Hatch-Washington House, at 216 Pollock, now houses one of the city’s historic restaurants.

Continue east to the intersection with East Front Street. Turn right on East Front and proceed a half-block south, where two impressive antebellum brick townhouses face each other. Located at 221 East Front, the Justice House was constructed in the Greek Revival style in 1843 for local merchant John Justice. Across the street, at 222 East Front, the three-story Sparrow House, built around 1840, is one of only seven brick side-hall houses surviving in the city.

Return to the intersection of East Front and Pollock streets. Walk west on Pollock. The Benjamin Ellis House, at 215 Pollock, has an unusual architectural history. This large, two-story frame dwelling was built in 1845. In 1900, it was cut in half and widened to its present six-bay form. It now serves as a bed-and-breakfast inn.

Cross Craven Street and continue west on Pollock. Located at 323 Pollock, the tall, heavily ornamented Baxter Clock has graced the downtown streets of New Bern since 1920. Believed to be one of only three of its kind still operating in the nation, this four-sided clock was built by Seth Thomas.

A state historical marker near the intersection of Pollock and Middle streets honors Caleb D. Bradham, one of the favorite sons of New Bern. For Americans who are curious as to why Pepsi-Cola advertises its products as the “Pride of the Carolinas,” the answer is found at the southeastern corner of Pollock and Middle. A small plaque attached to the outside wall of the corner jewelry store announces to the world that Pepsi-Cola was invented at this very spot.

Caleb D. Bradham acquired the nickname “Doc” because of his ability to fashion remedies in the basement of his pharmacy in downtown New Bern around the turn of the century.

Doc Bradham formulated a soft drink for his customers and began selling it at his soda fountain. His concoction, dubbed “Brad’s Drink,” was a hit with patrons. Inspired by the local success of his beverage and the growing acceptance of Coca-Cola, Bradham envisioned a larger market for his soft drink. Dissatisfied with its name, he spent a hundred dollars to acquire a registered brand name, Pep Kola, from a New Jersey company. To make his drink more marketable, he modified the name to Pepsi-Cola.

Unfortunately, after launching the enterprise, Bradham was ruined by the collapse of the sugar market following World War I. He had invested heavily in sugar when fears of a shortage had driven up the price. When the price of sugar plummeted, Bradham’s company was forced into bankruptcy.

Pepsi-Cola was saved from extinction by a New York company that acquired the rights to the drink and by a few distributors who had hoarded barrels of Pepsi at the time it became apparent that Bradham was going under. Doc Bradham died in 1935 without ever receiving the financial windfall his concoction produced. By that time, Pepsi-Cola was a national brand and a household name.

Continue along Pollock Street. At 320 Pollock, in the heart of the historic commercial district between Craven and Middle streets, Christ Episcopal Church is the first of the magnificent church buildings on this tour. This late Gothic Revival edifice, built around 1875, was constructed over the shell of the previous building, built in 1824.

Christ Church traces its roots to the parish formed here in 1741. Portions of the original church, King’s Chapel, built in 1750, are preserved on the grounds. Some of the oldest graves in the city are located around the church.

Open to the public on weekdays, the church holds rare treasures inside. Eight years before his death in 1760, King George II of England gave Christ Church a silver communion service, said to be America’s oldest. Created by royal decree, each piece of the service bears the royal arms of Great Britain. In addition to the service, the church also owns a Bible and a Book of Common Prayer, both gifts from King George II.

That the unique silver service has survived to this day is something of a miracle. When Royal Governor Josiah Martin hastily fled New Bern in 1775, he tried unsuccessfully to take the property of the church with him. After protecting the royal gift through the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, the church almost lost it during the Civil War, despite precautions against plunder. The Reverend A. A. Waters, rector of the church, delivered the set to Wilmington for safekeeping during the conflict. From there, it was transported inland to Fayetteville, where it was placed in the care of Dr. Joseph Huske. Marauding Federal troops subsequently ransacked Dr. Huske’s home, but they failed to discover the service, hidden under a pile of rubbish in a closet. Following the war, the service was returned to New Bern.

At the intersection of Pollock and Middle, turn north on Middle. Located at 317 Middle, in the middle of the first block, the Bank of the Arts is housed in an impressive Neoclassical Revival granite building constructed in 1913 for use by Peoples Bank. Now home to the Craven Arts Council, the building features a two-story public gallery with exhibits that change monthly.

Return to the intersection of Middle and Pollock and continue south on Middle for half a block to First Baptist Church. This dignified Gothic Revival structure is the second building constructed by the church, which was organized in 1809. Thomas and Son of New York designed the existing sanctuary. Since the church’s completion in 1848, a number of notable ministers have served here. William Hooper, founder of Wake Forest University, and Samuel Wait, the first president of that institution, were two of them. Thomas Meredith and Richard Furman, the men for whom Meredith College and Furman University were named, also pastored the church.

Walk back to the intersection of Middle and Pollock. Turn west on Pollock and proceed to the intersection with Hancock. Now serving as the office for the Neuse River Council of Governments, the Edward R. Stanly House, at 502 Pollock Street, was constructed in 1850 by a wealthy local manufacturer. Of particular interest on the exterior of the two-story, brick Greek Revival structure are the cast-iron window gables, the only such gables in the city.

Turn left and proceed south on Hancock Street. Two noteworthy eighteenth-century homes are located in the 200 block.

At 213 Hancock, the Patrick Gordon House was begun in the 1760s and completed a decade later. This frame Georgian dwelling with Federal elements is one of two pre-Revolutionary War gambrel-roofed houses in New Bern.

Also displaying a mixture of Georgian and Federal elements, the Benjamin Smith House, at 210 Hancock, is a splendid brick townhouse built in 1790. It was once owned by Governor Benjamin Smith, the namesake of Smithville (now Southport) and Smith Island (Bald Head Island). Because of its spectacular view of the river, the tall structure was used by troops from both armies during the Civil War.

Return to the intersection of Hancock and Pollock. Turn west on Pollock and proceed to its intersection with Metcalf. Constructed in 1801, the Bryan House, at 603–605 Pollock, is a stately brick townhouse with exquisitely carved ornamentation. The adjoining frame office was completed in 1820 by John Heritage Bryan, a United States congressman.

Located on the northern side of Pollock opposite the Bryan House, the New Bern Civil War Museum displays one of the most comprehensive private collections of Civil War memorabilia in the nation. Among the holdings are an assortment of weapons, accouterments, uniforms, and camp furniture. Built to preserve the Civil War heritage of New Bern, the museum opened in the spring of 1990.

In the midst of the tree-shaded residences in the 600 block of Pollock Street, visitors are overwhelmed by the visual grandeur that seems to rise from the Trent River, for here is the crowning glory of the city: the Tryon Palace restoration.

Thanks to the generosity of many history-minded North Carolinians, this structure, an exact replica of the palace known as the finest government house in the colonies, claims the honor as the major tourist attraction of New Bern. Since the Tryon Palace restoration officially opened to the public on April 8, 1959, its popularity has grown annually. Now, more than seventy-five thousand people a year tour the palace.

A tour of Tryon Palace begins at the visitor center, where a short audiovisual orientation program is offered in the auditorium. The visitor center is located on the northern side of Pollock Street just across from the palace.

Mighty oaks with limbs arching over a cobblestone drive grace the entrance to the palace. Costumed guides greet visitors as they enter the main building. As they walk over the marble floors of the entrance hall or ascend the wide staircase of mahogany and pegged walnut, guests marvel at the intricate workmanship in this restoration, which has, ironically, stood longer than the original palace.

The story behind the short existence of the original is fascinating. William Tryon, the newly appointed lieutenant governor of North Carolina, arrived in the colony on October 10, 1764, buoyed by assurances from London that Arthur Dobbs, the aged royal governor, was ready to relinquish his job in favor of his native Ireland. Tryon called on Dobbs at his home at Brunswick Town, where, much to Tryon’s chagrin, the governor was in good health and spirits. He had apparently fully recovered from a stroke suffered two years earlier, just after the seventy-four-year-old chief executive had married fifteen-year-old Justina Davis.

A year later, the thirty-five-year-old Tryon was en route to New Bern from Wilmington when his servant caught up with him bearing news that Governor Dobbs had died in the arms of his youthful wife. After officially assuming Dobbs’s position the following day, Tryon penned a letter to the Board of Trade in London with news of his predecessor’s death and his choice of New Bern as the site for the colonial capital.

When the colonial assembly convened at New Bern on November 8, 1765, Governor Tryon presented his request for an appropriation with which to construct a public edifice. This structure would serve as the house of colonial government as well as the governor’s residence. On December 1, the assembly overwhelmingly passed legislation providing seventy-five thousand dollars to purchase the land and to construct the necessary buildings.

Tryon had begun plans for his grand building even before he sailed from England. To guarantee that his future government house would be of the highest quality, he had persuaded John Hawks, a talented architect, to travel with him to North Carolina.

A strong hurricane ravaged New Bern in September 1769, destroying two-thirds of the buildings in the city, but Tryon’s luxurious masterpiece, which was in the final stages of construction, survived.

A gala was held on December 5, 1770, to celebrate the official opening. Cannon at Union Point fired salutes, music filled the air, and fireworks lit the night sky. For the first time in America, a colonial governor lived in and ran the government from the same building.

Tryon and his family enjoyed the palace less than a year, as he received a rather sudden appointment to the governorship of New York. Given the volatile state of affairs in North Carolina, Tryon was glad to leave.

His successor in North Carolina, Josiah Martin, arrived in New Bern to a hero’s welcome on August 11, 1771. Martin was accompanied by his wife and six children. For the next four years, Governor Martin spent much of his time lavishly furnishing the palace, aloof to the momentous events occurring in North Carolina and the other colonies. By the last day of May 1775, Martin found his position tenuous at best, so he and his family fled the town in a coach bound for the Cape Fear region.

After Martin abandoned the palace, it fell into disrepair. But when Richard Caswell, the first governor of the state of North Carolina, took his oath on January 16, 1777, he obtained legislative authority to restore the palace buildings and grounds.

Abner Nash, a Craven County resident living across the Trent River from New Bern, succeeded Caswell as governor in 1780. His occupancy of the palace was short, due to the threat of enemy invasion during the last years of the Revolutionary War. To sustain the war effort, much of the eight tons of lead used in the construction of the palace was stripped away, to be melted into musket balls.

The victorious conclusion of the Revolutionary War did not signal brighter days for the palace. Ultimately, intruders stripped the once-grand lady of carpets, locks, and panels of glass. Vagrants sought shelter where the affairs of the colony and the state had once been administered. A bayonet fight among drunks left one of their number dead on the kitchen floor.

Governor Richard Dobbs Spaight, who had earlier owned several of the lots on which the structure was erected, took his oath of office in the palace in December 1792. After the legislature held a final session in New Bern in 1794, the building’s days were numbered.

For the next four years, New Bern Academy held classes in the council chambers, its schoolmaster residing on the second floor. On the night of February 27, 1798, he sent a young servant to search for eggs in the hay cellar. While on her mission, the servant accidentally set the hay on fire with her torch. Church bells tolled throughout the wee hours of the morning, summoning volunteers to fight the fire. In haste, a hole was cut through the grand staircase to the outside. Flames engulfed the main building. Ashes and smoldering ruins were all that remained of the historic structure the following morning, though the firefighters did manage to save the outbuildings.

Over the next 150 years, the surviving western wing bore little resemblance to the dignified government building that it once represented.

In the 1930s, Governor Gregg Cherry created the twenty-five-member Tryon Palace Commission in response to mounting interest in a possible restoration project. A legislative appropriation of $287,000 allowed the commission to purchase the lots in the original Palace Square, which by that time was covered with fifty-four deteriorating houses slated for demolition.

Were it not for the hard work, dedicated leadership, and philanthropy of the commission chairperson, Maude Moore Latham, the palace would most likely never have been rebuilt. Latham, a New Bern native who had played in the ruins of the palace as a child, established a living trust of $225,000 and bequeathed another $1,116,000 for the restoration she did not live to see completed. She also acquired $125,000 in antiques to partially furnish the new palace. Her daughter, Mrs. John A. Kellenberger, succeeded her as chairperson and steered the project to a successful completion.

William G. Perry, a noted architect from the Boston firm that restored Colonial Williamsburg, began his work in New Bern in 1951. He had the benefit of original copies of the palace drawings by John Hawks. Construction on the restoration commenced in 1953 after years of planning.

Today, virtually every nook and cranny of the palace is visible on the tour. In addition to the two main stories, the tour includes the large attic and cellar. Extreme care was taken in the $3.5-million restoration project to make the entire forty-room structure appear as close to the original as possible.

More than $5 million in period antiques adds to the elegance of the palace interior. Aided by an inventory of William Tryon’s original furnishings, the commission has assembled some seven thousand art objects and pieces of furniture to reflect the atmosphere of the palace during the tenure of the royal governor.

On one side of the main building, the eastern wing has been meticulously restored as the kitchen. On the other side, the western wing, with 85 percent of its original brickwork remaining, is the only part of the structure that has survived since 1770. It has been restored as a stable, carriage house, and granary. Among the support buildings around the palace are a smokehouse, a greenhouse, and a crafts demonstration shed. A garden shop adjacent to the eastern wing sells plants to the public.

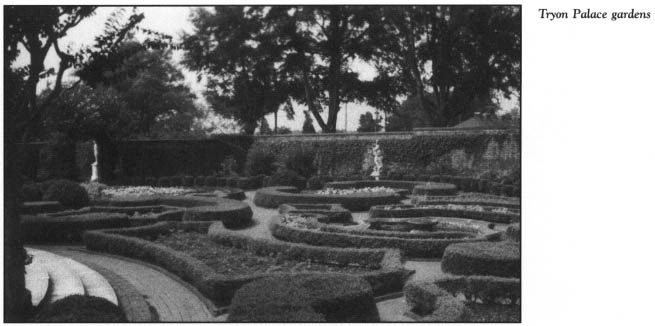

Not to be missed are the beautifully landscaped grounds and gardens overlooking the river. Most prominent among the half-dozen or so gardens is the Maude Moore Latham Garden. This formal garden of clipped dwarf yaupon in geometric patterns typifies the English garden of Governor Tryon’s time. Other nearby flower gardens are ablaze with tulips in the spring and chrysanthemums in the autumn.

Five other houses have been restored as part of the complex.

Located on the eastern front side of the palace, at 609 Pollock Street, the Stevenson House is open to the public. Portions of the two-and-a-half-story, gable-roofed, side-hall dwelling date from 1805. It was constructed on one of the original palace lots by a wealthy sea captain. On the inside, visitors are treated to original hand-carved woodwork and rare antiques of the Empire and Federal periods.

Just across the street, at the corner of Pollock and George streets, stands the Commission House (Lehman-Duffy House). Not open to the public, this two-story Italianate-style dwelling was constructed in 1886 on the frame of an earlier home. It now houses the administrative offices of the restoration complex.

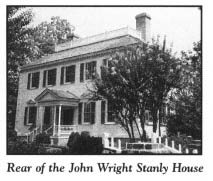

From the Commission House, turn right and proceed north to 307 George Street to visit the John Wright Stanly House, the second of the complex’s houses open to the public for tours. Built between 1779 and 1783, this massive, two-story frame mansion is considered one of the most elegant late Georgian houses in America. To the rear of the house is the unique, formal Town House Parterre garden, which was a favorite of First Lady Pat Nixon.

Architecture experts have deemed the sumptuous interior of the John Wright Stanly House the most sophisticated in New Bern, save the interior of the palace itself. The antique woodwork, especially the Chippendale staircase, is eye-catching. Historians believe that many of the craftsmen who worked at the original palace also labored at the Stanly mansion.

Not only is the existing structure fascinating, but so, too, are the stories of the Stanly family and the visitors to the house in the late eighteenth century. John Wright Stanly, the man for whom the house was built, was one of America’s foremost patriots during the Revolutionary War. Ironically, Stanly traced his lineage to the throne of King Edward I of England. Inscribed upon the Stanly family’s coat of arms were words meaning “always loyal.”

Stanly settled in New Bern in the early 1770s, after a treacherous storm in the Graveyard of the Atlantic forced him ashore on the North Carolina coast. In the years leading up to the Revolutionary War, Stanly used his business acumen to achieve great success as a shipping magnate. Guided by his longstanding rebellious attitude toward England, Stanly used fifteen of his ships to form a personal privateer fleet, which raided and even did combat with English ships throughout the war.

As one of the most prominent financiers of the American Revolution, he became a marked man, living in constant danger. On Sunday, August 20, 1781, his life was spared only because he was out of town when the enemy came calling. Though Stanly was not harmed physically, his ships, wharves, and home were torched.

In the postwar years, Stanly called on his friend and fellow church member John Hawks to design a mansion to meet the needs of his growing family. Completed at a cost of thirty thousand dollars, the structure was the home of Mr. and Mrs. Stanly until they died of yellow fever within a month of each other in 1789.

Thereafter, the Stanly descendants entertained many famous guests in the home. On his Southern tour in 1791, President George Washington spent two nights in New Bern at the mansion. He described it as “exceedingly good lodgings.” A state historical marker on Pollock Street just around the corner from the house notes Washington’s visit. General Nathanael Greene and the Marquis de Lafayette also enjoyed the hospitality of the Stanly home.

One of John Wright Stanly’s sons, also named John, was a brilliant attorney and a United States congressman who became embroiled in a bitter dispute with Richard Dobbs Spaight, the former governor of North Carolina, over a Senate election in 1802. A duel between the two politicians ensued, resulting in the death of Spaight. Ironically, when descendants of the Spaight family moved into the Stanly house in the latter part of the nineteenth century, neighbors reported seeing ghosts in and about the mansion. Stanly County, North Carolina, was named in honor of John Stanly.

Confederate general Lewis Addison Armistead, the grandson of John Stanly and the great-grandson of John Wright Stanly, was born in the house in 1817. Armistead was killed on July 3, 1863, while leading a portion of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. Ironically, Union general Ambrose Burnside chose the Stanly mansion as his first headquarters during the occupation of New Bern during the Civil War. It was subsequently used as a hospital for Union troops.

From time to time, the Stanly descendants lend family heirlooms—including fine portraits of John Wright and Ann Stanly, household items used by George Washington when he was a house guest, and the dueling pistol that killed Governor Spaight—for display at the house.

Although it now stands a few hundred yards north of the palace, the Stanly mansion was erected on New Street between Middle and Hancock streets. Around 1935, it was moved to the present location, where it was restored for use as the public library. It was given to the Tryon Palace Commission in 1966.

Return to the intersection of George and Pollock streets. On the western front side of the palace stands the McKinlay-Daves-Duffy House, at 613 Pollock. Built around 1813, this home is owned by the commission but is not open to the public. The two-story, frame, side-hall-plan house was constructed in the Federal style. It was moved to its present site in the late 1950s so the palace gardens could be developed.

Cross Eden Street, the circular drive around the palace, to the 700 block of Pollock. Located at the corner of Pollock and Eden, the two-story, frame Jones House, built around 1808, houses the palace’s gift shop. Emeline Pigott, a Confederate spy and heroine of coastal North Carolina, was imprisoned in this house during the Civil War.

Continue west on Pollock, away from the restoration complex. Three Georgian-style houses—the John Chadwick House at 712 Pollock, the John Horner Hill House at 713 Pollock, and the Green-Wade House at 726 Pollock—date from 1770 to 1795.

Located at 717 Pollock, the Carruthers-Forbes House features a 1760 cottage that became the attached wing of a two-and-a-half-story side-hall dwelling built in 1810.

Cross Bern Street to the 800 block of Pollock. At least a half-dozen Federal-style houses of note are located here: the Nathan Tisdale House at 803 Pollock, built around 1800; the Anne Greene Lane House at 804 Pollock, built around 1805; the Osgood Cottage at 807 Pollock, built around 1820; the Bryan Jones House at 812 Pollock, built around 1830; the Elizabeth Thomas House (Silas Statham House) at 816 Pollock, built around 1810; and the John H. Jones House at 819 Pollock, built around 1810.

Three other structures in the 800 block are of architectural significance. The Pendleton House at 815 Pollock, built around 1800, and the Alston-Charlotte House at 823 Pollock, built before 1770, are gambrel-roofed dwellings. Located at 809 Pollock, All Saints Chapel serves as the arts-and-crafts store of the New Bern Historical Society. Constructed in 1895 as a mission chapel of Christ Episcopal Church, the handsome, frame Gothic Revival structure was deconsecrated in the late 1930s.

Return east to the intersection of Pollock and Bern. Turn left and walk north on Bern. Located at 300 Bern, the Thomas Cottage represents an outstanding example of the efforts of New Bern citizens to restore their past. This handsome, frame story-and-a-half Federal cottage was constructed in the early nineteenth century. Its restoration in the late 1970s preserved most of its rich architectural detail.

Continue on Bern Street to the intersection with Broad Street. Turn right and proceed 1 block east on Broad to its intersection with George Street. A state historical marker for Tryon Palace stands at this corner. Located near the marker at 701 Broad, the Joseph L. Rhem House is an elegant Greek Revival and Italianate mansion built around 1855 by the owner of a turpentine distillery. Its present Colonial Revival appearance is the result of a remodeling project in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

Cross George Street and continue east on Broad. Located on a shaded lot at 613 Broad, the William Hollister House is an impressive two-and-a-half-story structure built in 1840. A widow’s walk adorns the roof of this dwelling, which combines the Federal and Greek Revival styles.

Cross Metcalf and continue on Broad. Three significant structures are found on this block.

Located at 515 Broad, the Attmore-Wadsworth House is an unusual structure built around 1850 as a combination office and residence. Subsequent additions to the sprawling one-story building have given it a combination of late Greek Revival, Italianate, and Colonial Revival details.

Next door at 513 Broad stands the Attmore-Oliver House, now the home of the Attmore-Oliver House Museum and the New Bern Historical Society. Constructed in 1790 and enlarged in 1834, the stately building features two different facades. Its Broad Street front exhibits exquisite Greek Revival ornamentation, while the rear facade features two-story porches of the late Federal period. Inside, the museum offers antiques of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and Civil War artifacts. A state historical marker near the museum chronicles the duel between Governor Spaight and Congressman Stanly.

Located on the northern side of the street at 518 Broad, the two-story Ulysses S. Mace House is one of the finest Italianate structures in the city. It was constructed in 1884 by a local pharmacist.

Walk east on Broad to the intersection with Hancock. Turn left on Hancock and proceed north half a block to the New Bern Firemen’s Museum, at 410 Hancock.

More often than not, historic gems are hidden in old cities, waiting for discovery. Housed in an old, one-story building behind New Bern’s main fire station, this museum is one such hidden treasure. It was opened to the public in 1957 by the two oldest continuously operating fire companies in the United States: the Atlantic Company, organized in 1845, and the Button Company, organized twenty years later. In 1900, the latter company set two world firefighting records for the production of steam. These records have never been broken.

Visitors to the museum enjoy an interesting, unique collection of antique fire engines and other firefighting equipment. Without question, the most sentimental exhibit is that of Fred, the most beloved firefighter in New Bern history. Fred joined the Atlantic Company in 1908 in the days before New Bern had motorized fire engines. This amazing horse was assigned to duty pulling a hose wagon, and he quickly became an invaluable member of the company. As soon as the fire alarm sounded, Fred backed into the wagon stall so his harness could quickly be dropped over his head. Firemen took pride in the special horse that always tried to get to his hose as soon as possible.

By 1915, New Bern obtained two motorized fire engines. Yet Fred’s days of service were far from over. When the opportunity presented itself, the animal attempted to race the “horseless carriage” to a fire.

Fred again proved his mettle in 1922, when he was in the thick of the fight against the worst fire in the history of the town.

No matter when a call came, the horse always responded. He dropped dead in his harness in 1925 while answering an alarm from Box 57, at New Banks and North streets. His death in the line of duty proved to be a tragedy when it was discovered that the alarm was false.

To honor Fred’s memory, the firemen of Atlantic Company decided to have his head mounted. It was displayed at the fire station until the museum opened. Since that time, it has been preserved and exhibited in a glass display case.

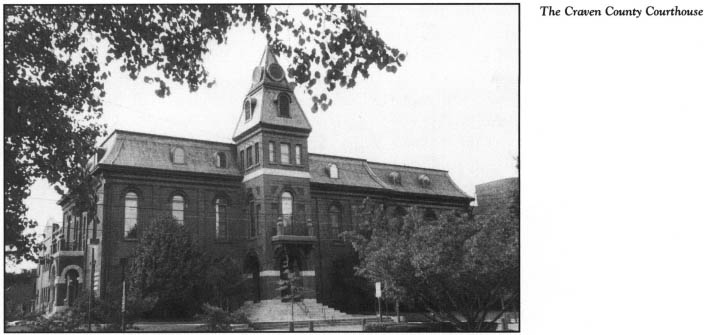

Return to the intersection of Hancock and Broad and turn east on Broad. Cross Middle Street and walk to the Craven County Courthouse, located on the northeastern corner of Broad and Craven streets.

The Craven County Courthouse is the largest Second Empire-style building in the city. Designed by Philadelphia architects Sloan and Balderson, the two-and-a-half-story brick structure was completed in 1883 as the county’s fourth courthouse.

A large boulder on the courthouse lawn memorializes the three New Bernians who have served as governor of North Carolina.

On the street in the shadow of the stately courthouse stands a pair of state historical markers that boast of two of the “firsts” for which New Bern is famous. One sign commemorates the First Provincial Congress, held in open defiance of British orders. It convened in New Bern on August 25, 1774, with seventy-one delegates present. The other marker describes the first printing press in North Carolina. This press was set up near the site of the present courthouse in 1749 by James Davis, who published the first book, the first newspaper, and the first pamphlet in the colony.

Because of its significant historical and cultural achievements during the colonial period and the early days of statehood, New Bern acquired the soubriquet “Athens of North Carolina.” Among the firsts claimed by this river town are the following: New Bern was the first town in America to celebrate George Washington’s birthday; it was the first town in North Carolina and the third in America, after Boston and Philadelphia, to celebrate Independence Day; it was the site of the first incorporated school in North Carolina and the second private secondary school in English America to receive a charter; it was the site of the first free school for white children and the first public school for blacks in North Carolina; it was North Carolina’s first state capital; it was the site of the first inauguration of state officials; it was the site of the first meeting of the state legislature; it was the site of the first post office in North Carolina under the American republic; it was the site of the first public banking institution in the state; it was the site of the first bookstore in North Carolina; and it was the first town in North Carolina to decorate its streets with multicolored electric lights at Christmas.

When you have enjoyed the courthouse, return to your car by turning south off Broad onto Craven and walking to Pollock, where the walking tour started.

Drive north on Craven to its intersection with Broad. Turn right, or east, onto Broad. On the northern side of Broad near its intersection with East Front stands the Sudan Shrine Temple, the sixteenth-largest Shrine temple in the nation.

Turn left, or north, off Broad onto East Front. Located on the waterfront near the bridge over the Neuse River are two state historical markers. One honors Christophe DeGraffenried, while the other details the Battle of New Bern.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, New Bern was recognized as an extremely significant port by both armies and by President Lincoln. Not only was the town the second-largest city on the North Carolina coast, but its east-west railroad was vital to the state’s transportation network.

On March 11, 1862, a month after General Ambrose Burnside captured Roanoke Island, Lincoln and his advisers ordered Burnside to advance on New Bern with three brigades and supporting artillery. A fleet of Union warships and transports made its way down Pamlico Sound, reaching the Neuse River on March 12.

New Bern was defended by four thousand Confederate troops under the skillful command of a native North Carolinian, Brigadier General Lawrence O. Branch. A graduate of Princeton and a former United States congressman, Branch knew that his forces were outnumbered more than three to one.

On March 14, General Burnside led Union naval and marine forces in one of the first combined amphibious assaults in United States history. Hordes of his troops stormed ashore at New Bern. Once the landing was accomplished, the Union troops battled the defenders from seven-thirty that morning until noon, when General Branch ordered his army to retreat.

Fighting valiantly side by side for the Confederates during the fall of New Bern were two young North Carolina colonels whose names would become well known to all New Bernians as the war progressed. Colonel Zebulon B. Vance would be elected governor of North Carolina later that same year, and Lieutenant Colonel Robert F. Hoke, later a general, would return to the city on several occasions in an attempt to liberate it from Union occupation.

Despite the nearly impregnable defense system of ten forts, a cavalry camp, and two blockhouses subsequently set up around the town by the Union occupation forces, the Confederates were anxious to retake New Bern. Expeditions led by Major General Daniel Harvey Hill and Major General George Pickett in March 1863 and January 1864 failed miserably. However, after his impressive victory at Plymouth in mid-April 1864, Major General Robert F. Hoke laid siege to, and demanded the surrender of, New Bern on May 4. But before he could retake the town, Hoke and his troops were ordered to Virginia, where Lee was being challenged near Petersburg.

The restored cannon on the waterfront walkway near the historical markers is not of Civil War vintage. Rather, it was unearthed in the center of town in the 1920s and is believed to be one of the original cannon from Tryon Palace.

In 1962, President John F. Kennedy visited the area to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of one of the nation’s military firsts, the combined amphibious assault on New Bern.

Continue north on East Front Street to its intersection with New Street. This site along the waterfront is known as Council Bluff. It was here that DeGraffenried and his settlers landed in 1710.

Across the street from the waterfront, at 501 East Front, is the Coor-Bishop House. This lavish Georgian mansion, remodeled in the Colonial Revival style, was built between 1770 and 1778 by James Coor, a local real-estate speculator. George Pollock, a subsequent owner and one of the wealthiest men in the state, entertained President James Monroe and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun at the residence in 1819. When the house was remodeled in 1903, it was turned ninety degrees from its original orientation on New Street.

Turn left, or west, off East Front Street onto New Street. Located at 219 New, the Cox-Stewart House was built between 1785 and 1790 in the Georgian style. An addition in 1810 gave the two-story frame structure its Federal touches.

Continue west on New across Craven. Now used as the eastern office of the governor of North Carolina, the Coor-Gaston House, at the southwestern corner of New and Craven streets, was built in 1770 by Colonel James Coor, a prominent politician who served in the North Carolina General Assembly from 1777 to 1792. At the time of its construction, the house exhibited a feature unique among New Bern dwellings: double porches engaged beneath the main gabled roof.

In 1819, the elegant, two-story Georgian townhouse was purchased by William Gaston, one of the truly great men of nineteenth-century North Carolina. Gaston served in the United States Congress and on the North Carolina Supreme Court. He also wrote the official state song, “The Old North State.” Gaston County, North Carolina, bears his name.

Located at the southeastern corner of New and Middle streets one block west of the Coor-Gaston House, Centenary United Methodist Church was the first major church building constructed in the city in the twentieth century. Built in 1904, the appealing Romanesque Revival structure features several turrets, which give it a castlelike appearance.

When the monumental Federal Building was constructed at the southwestern corner of New and Middle streets in 1935, the three-story brick structure was deemed too large and extravagant for a city the size of New Bern. Murals in the courtroom detail important events in the history of the city.

Turn right, or north, off New onto Middle Street. St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church, at 510 Middle, is not only the oldest Catholic church in North Carolina, but also the home of the oldest Catholic congregation in the state. Erected in 1839, the tall, graceful frame edifice has been altered very little since that time. William Gaston, a devout Catholic, inspired the establishment of St. Paul’s when he brought Bishop John England to New Bern in 1821 to celebrate the first Catholic mass in the city.

Located just across Middle Street, the Chester B’nai Sholom Synagogue has served as the principal house of worship for Jews in New Bern since 1908. Although it is unclear where they worshipped before this Neoclassical temple-style structure was constructed, there is evidence of a local Jewish community as early as 1824.

Adjacent to the temple, the McLin-Hancock House, built around 1810, is a Federal-style cottage known for its strict symmetry.

Proceed to the intersection of Middle and Johnson streets and turn left, or west, onto Johnson. After 1 block, turn left, or south, on Hancock.

Constructed between 1801 and 1809, St. John’s Masonic Lodge and Theater, at 516 Hancock, features a second-floor lodge room with original Federal woodwork and walls painted with symbolic trompe l’oeil Masonic decorations. Presidents Washington and Monroe visited the lodge while in the city. Located on the first floor of the building, the Masonic Theater is the oldest theater in the United States still used for that purpose.

Nearby at 521 Hancock stands the Coor-Cook House, built by James Coor in 1790. This large, two-and-a-half-story frame structure was moved from Craven Street to its present location in 1981 to make room for the expansion of the county courthouse.

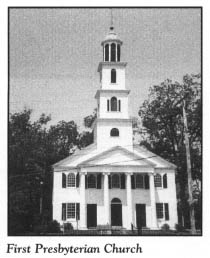

Drive to the intersection of Hancock and New streets and park in the parking lot on Hancock. Walk to the northern side of New Street to visit First Presbyterian Church, located at 412 New.

Of all of New Bern’s architectural masterpieces, none, including Tryon Palace, is more awe-inspiring than First Presbyterian. Dignified by its tidy white exterior and tall frontal columns, the majestic wooden structure is considered one of the most beautiful religious edifices in all of America.

An interior like that of First Presbyterian can be found in only one other church in America: the Congregational Church of Litchfield, Connecticut. Both structures were built from plans drawn by Sir Christopher Wren, England’s most famous church architect.

New Bern Presbyterians purchased the church site in 1819. Three years later, the building was completed under the supervision of architect Uriah Sandy.

One of the final matters to be attended to prior to the opening of the church was the sale and rental of pews. Depending upon their location, pews were sold to members for prices ranging from $350 for center seating to $150 for side pews. Members who could not afford to buy or rent pews were not denied seating. Instead, a few pews near the front, known as “Stranger’s Pews,” were free to all.

Since 1822, the exterior of the church has changed little. Visitors marvel at the classic architectural features embodied in the building: a pedimented Ionic portico, a fanlight above the central entrance, and a square tower diminishing in five stages to an octagonal cupola. On the interior, the sloping floor is an extraordinary feature for a structure of its time. A balcony encircles the entire sanctuary except for the raised “swallow’s nest” pulpit.

Return to the parking lot and drive west on New Street to the New Bern Academy Museum, at 508 New.

When noted cartographer C. J. Sauthier drew his map of New Bern in 1769, he represented New Bern Academy as a small box on the outskirts of town. The academy was a wooden building erected in 1766 as a result of legislation in 1764 that authorized the incorporation of the first school in North Carolina. After the original school building burned, the academy moved to the vacant Tryon Palace in 1790. Eight years later, the academy was once again without a home when the palace was consumed by fire.

Funds for the existing two-story, cupola-topped Federal-style building came from a state-authorized lottery. The structure was completed in 1810. From the outset, the school enjoyed an excellent reputation. An early visitor from Rhode Island deemed it “one of the best regulated schools of its kind in America.”

A second building, the Bell Building, was constructed nearby at 517 Hancock Street in 1884. Fourteen years later, the buildings were merged into the New Bern city school system. Central School, as the combined campus of the old academy and the Bell Building was known thereafter, operated until 1971.

In the fall of 1990, the New Bern Academy Museum opened as a major component of the Tryon Palace restoration. The building contains four large rooms, each filled with exhibits centered around four themes: the general history of New Bern, the architecture of the city, the Civil War in the city, and the history of education in New Bern.

Three houses of historic importance are located near the academy in the 500 block of New Street.

The Cutting-Allen House, at 518 New, was saved from demolition and moved to its present site in 1980. Constructed in 1793, this side-hall house with late Georgian and early Federal elements features a large rear ballroom.

Located next door at 520 New, the Palmer-Tisdale House was built in two sections. Its Georgian front section was constructed in 1767, and the rear section was added in 1800 for Judge John Louis Taylor, who later served as the first chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court.

Just across the street at the corner of New and Metcalf, the Hawks House dates from 1769. It was once the home of Francis Hawks, the local customs collector and the son of the architect of Tryon Palace.

Drive west 1 block on New Street and turn right, or north, onto George Street, which becomes National Avenue after 1 block.

Situated on a block bounded by National Avenue and Queen Street, the expansive Cedar Grove Cemetery was begun by Christ Episcopal Church as a response to a yellow-fever epidemic in 1798. Visitors are greeted at the cemetery entrance on Queen Street by a beautiful Roman triumphal arch made of coquina. A legend behind the arch holds that if water drips on a person entering through it, that person will soon die.

Many of the most famous citizens of New Bern, including William Gaston, are buried here. Among the many impressive monuments is the Confederate Monument, erected in 1885 atop the underground Confederate vault.

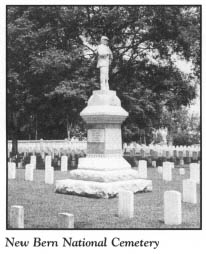

Continue north on National Avenue for 0.9 mile to New Bern National Cemetery.

In February 1867, the United States Congress authorized the development of this 7.5-acre cemetery on the outskirts of the city. Soon thereafter, the remains of approximately a thousand Union soldiers who died in New Bern of war wounds or yellow fever were moved to the new cemetery from Cedar Grove Cemetery. Four states—Vermont, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Rhode Island—have erected monuments here to honor their Civil War dead.

One of the bodies reinterred in 1867 was that of Carrie E. Cutter, the only woman buried with the initial group of soldiers. Cutter came to New Bern in 1864 to administer to her fiance, Charles E. Coolidge, a Union army private from Massachusetts who was suffering from yellow fever. After Coolidge succumbed, his weakened, heartsick girlfriend also fell prey to the disease and died shortly thereafter. Her dying wish was to be buried beside Private Coolidge.

The beautifully landscaped cemetery features one tree of particular interest. A giant redwood brought to New Bern from California just after the Civil War is said to be one of only three such trees on the entire Atlantic coast.

Retrace your route south on National Avenue to the intersection with Queen Street. Turn left and proceed east on Queen for 1 block, then turn right, or east, onto Johnson Street. Proceed 3 blocks to the 300 block, where four houses—the Captain Elijah Willis House at 311 Johnson, the Thomas Jerkins House at 309 Johnson, the John D. Flanner House at 305 Johnson, and the Jerkins-Duffy House at 301 Johnson—date from before 1855.

Continue to the next block. The Brinson House at 213 Johnson, built around 1770, and the Mitchell-Stevenson House at 211 Johnson, built around 1800, display the late Federal style.

Located at the southwestern corner of Johnson and East Front, the Charles Slover House is the oldest Greek Revival house in New Bern and one of the finest in the state. This elegant three-story brick mansion was erected in 1848 and has remained virtually unaltered since its construction. During the Civil War, General Ambrose Burnside used the house as his headquarters. It was purchased in 1908 by Caleb Bradham, the inventor of Pepsi-Cola.

Turn left, or north, on East Front. Located at 607 East Front is the birthplace and boyhood home of the famous Rains brothers. Both men, educated at West Point, were inventors and geniuses in the field of explosives. General James G. Rains invented the land mine and developed naval torpedoes for the Confederate war effort. His brother, Colonel George Washington Rains, was in charge of the procurement of gunpowder for the Confederacy. His powder mills produced 2,750,000 pounds of gunpowder during the war. Their early-nineteenth-century house was moved to its present site from Johnson Street in order to make room for an expansion of the public library.

Turn around and drive south on East Front Street. Built in 1810, the Jones-Jarvis House at 528 East Front is nearly identical in appearance to the nearby Eli Smallwood House at 524 East Front, built around 1810. Both are among the finest brick Federal side-hall-plan houses in the city.

Constructed in 1885 in the Italianate style, the Samuel W. Smallwood House, at 520 East Front, is best known for the historic trees in its backyard on the Neuse River. A famous cypress tree believed to be between seven hundred and a thousand years old is one of the twenty trees in the Hall of Fame of American Trees. Legend holds that during the Revolutionary War, General Nathanael Greene met under this tree with local patriots to receive a pledge of substantial financial assistance. When he visited New Bern after the war, President Washington asked to see the tree where America’s fortunes of war turned.

The Dawson-Clarke House, better known as the Louisiana House, is located at 519 East Front. This home is best known for its most famous resident, Mary Bayard Devereux Clarke (1827–1886). A North Carolina native, Clarke was one of the most famous poets in the state in the nineteenth century. She published a two-volume anthology of North Carolina poetry, Wood-Notes, in 1854. Clarke’s two-story frame house, built in 1807, was so named because of her stay on a Louisiana plantation prior to the Civil War.

Gull Harbor, a two-and-a-half-story, frame Federal house, was constructed at 514 East Front in 1815. It stands on the site of the birthplace of Elizabeth Shine, the mother of Admiral David Farragut.

Continue south on East Front to its intersection with Tryon Palace Drive. Turn right, or west, onto Tryon Palace Drive and park at Bicentennial Park. The tour ends here, at this expansive park on the Trent River, with its scenic view of the modern New Bern waterfront.