This tour begins at the intersection of U.S. 17/74 and N.C. 132 on the northern side of Wilmington.

This tour begins with a visit to Carolco Studios, on the northeastern side of Wilmington, then heads toward the Wilmington Historic District for a walking tour of the area along the river, which is packed with historical and architectural treasures. The driving tour wraps up with visits to Greenfield Park and the North Carolina State Port at Wilmington.

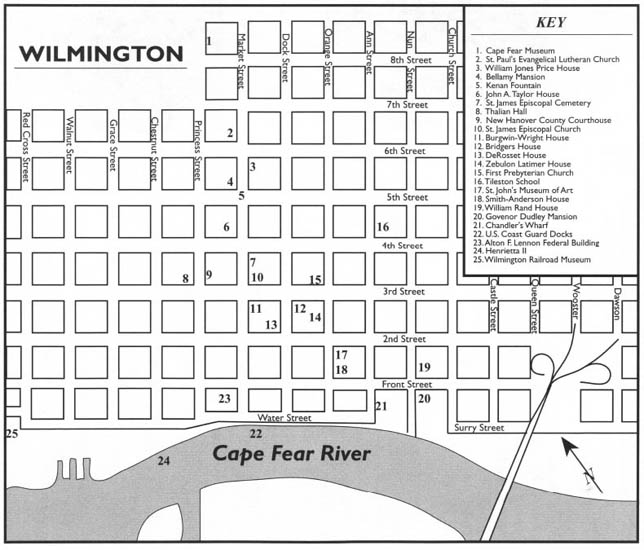

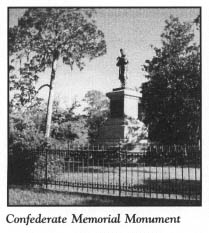

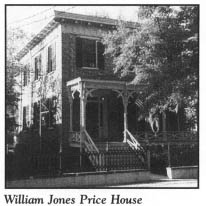

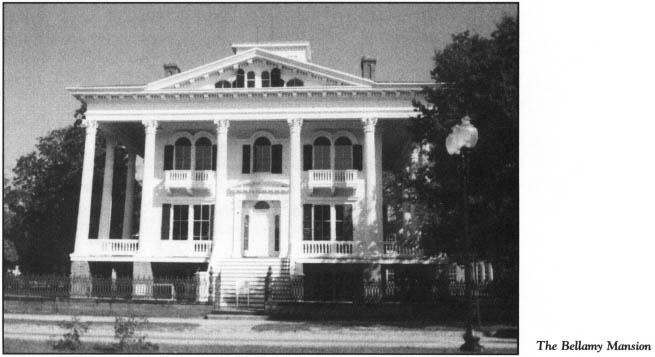

Among the highlights of the tour are Wilmington National Cemetery, Oakdale Cemetery, the Cape Fear Museum, the William Jones Price House, the Bellamy Mansion, the Wilmington Railroad Museum, Riverfront Park, the Governor Dudley Mansion, the St. John’s Museum of Art, the Burgwin-Wright House, the story of the tunnels under Wilmington, St. James Episcopal Church and its cemetery, the Zebulon Latimer House, and Thalian Hall.

Total mileage: approximately 9 miles.

Of the many jewels of the North Carolina coast, none sparkles more brightly than the magnificent port city of Wilmington. Strikingly beautiful both naturally and architecturally, historically significant, and economically dominant in the coastal region, Wilmington wears many hats well.

Proceed west on U.S. 17/74 (Market Street) for approximately 2.5 miles to Twenty-third Street. En route, you will glimpse the suburbs and sprawling commercial development of the city that remains the largest on the North Carolina coast. In a state that has been predominantly rural throughout its history, Wilmington has long been a population leader. Until the dawn of the twentieth century, it was the most populous city in the state. While other cities to the west have since surpassed it in size, none has been able to match the unique grace and charm bestowed upon Wilmington by history.

Turn right on Twenty-third Street and drive 8 blocks north to the entrance to Carolco Studios, at 1223 North Twenty-third.

As the undisputed king of commerce in coastal North Carolina, Wilmington boasts a diverse business community. Since the 1980s, the local economy has received a substantial boost from the film industry, which has made Wilmington “the Hollywood of the East.”

Located on thirty-two acres, Carolco Studios owns one of the largest movie and television production facilities outside Hollywood. Although the complex is not open for public tours, a cafe adjacent to the lot provides an opportunity for tourists to watch the comings and goings at the studios. Moreover, feature films and television shows are regularly shot in and around Wilmington, thereby giving the public closeup views of the industry. Screen stars can often be seen patronizing local restaurants and businesses.

In 1984, Italian movie mogul Dino De Laurentiis chose Wilmington over Charleston, South Carolina, as the location for his only active permanent studio. He had become enamored with Wilmington while filming Stephen King’s Firestarter at nearby Orton Plantation in 1983. After De Laurentiis settled on Wilmington, a huge motion-picture complex—complete with more than a half-dozen sound stages, a two-hundred-seat commissary, a gourmet food shop, a cinema, and production facilities—went up almost overnight in the sandy, gray soil just a few blocks from Wilmington International Airport.

From 1984 to 1987, DEG Studios, De Laurentiis’s parent company, churned out twenty-five full-length films at the Wilmington facility. On occasion, downtown Wilmington was transformed into New York’s Times Square or downtown Boston. Nearby Airlie Gardens temporarily became King Kong’s boyhood home in Borneo. However, in late 1987, the sound stages suddenly grew quiet. Financial problems forced DEG Studios into bankruptcy, and for a short period, it appeared that “Hollywood East” would be no more.

Carolco Pictures, the independent production company that brought such blockbusters as Rambo, Total Recall, Cliffhanger, and Basic Instinct to the screen, took control of the Wilmington studio in 1989. Since that time, Carolco Studios has become one of the busiest film facilities in the nation. It encompasses eight sound stages, the world’s largest backlit blue screen for special effects, and a back lot featuring a three-block-long, four-story-high urban street that has been used to portray New York, Chicago, Detroit, and New Orleans.

More than eighty motion pictures—among them Betsy’s Wedding, Sleeping with the Enemy, Billy Bathgate, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, The Crow, Date with an Angel, Silver Bullet, Marie, Year of the Dragon, The Hudsucker Proxy, Maximum Overdrive, Super Mario Brothers, Amos and Andrew, Blue Velvet, Loose Cannons, and King Kong Lives—have been produced at the Wilmington studio. Additionally, the television series “Matlock” and “The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles” have regularly been filmed here. This heavy activity at Carolco has helped North Carolina rank third—behind only California and New York—in movie production in the United States.

Return to the intersection of Twenty-third and Market streets. Turn right and drive west on Market to Twentieth Street. Turn right, or north, at the entrance to Wilmington National Cemetery.

Although the two large, historic cemeteries of the city—Wilmington National and Oakdale—are not listed among the museums of Wilmington, they probably should be. Located on a beautiful five-acre tract along Burnt Mill Creek, Wilmington National Cemetery was established in 1867. It was intended for the proper interment of Union soldiers who had been hastily buried near the spots where they fell—along the railroads leading out of the city, along the Cape Fear River, and at Fort Fisher and Southport, near the mouth of the river. Most of the Civil War dead were removed to the cemetery in 1867.

The low brick wall surmounted with ironwork along the Market Street side of the cemetery was constructed in 1934. It allows a spectacular view from the street. This wall replaced the original high wall, which, ironically enough, was fabricated of sandstone from Manassas, Virginia, near the site of the early Civil War battle. The brick walls enclosing the other three sides of the cemetery were built between 1875 and 1878.

Inside the walls, white gravestones, virtually all of them government issue, have been neatly placed in long, straight rows. Each of the stones faces east, in conformity with the belief that the dead should face the rising sun. Most of the stones mark the resting places of American soldiers from every war in which America has been involved, from the Civil War to Vietnam. Nearly sixteen hundred unknown soldiers are interred at the cemetery.

Not all of the people buried here are veterans of the armed services. One of the most famous civilians is novelist Inglis Fletcher. Her funeral in 1969 attracted many well-known authors to Wilmington. She was buried in a grave northwest of the flag circle beside her husband, John A. Fletcher, a veteran of the Spanish-American War.

Return to Market Street and continue west. In the 1700 block of Market, towering, ancient oaks veiled with Spanish moss form a canopy over the relatively narrow highway into downtown Wilmington. Gracing both sides of the street are handsome mansions built in the early nineteenth century, when this area was the streetcar suburb of the city.

Continue west on Market to its intersection with Fifteenth Street, the location of a state historical marker for Oakdale Cemetery. Turn right and drive north on Fifteenth to the historic cemetery, located at the end of the street.

This cemetery is one of the special places in Wilmington that visitors often overlook. Its secluded location deep within a residential section keeps it hidden from many tourists. Still others intentionally leave the ancient graveyard off their itinerary due to the misconception that it is nothing more than an ordinary burial ground.

To the contrary, Oakdale is one of the most peaceful, beautiful spots in all of coastal North Carolina. Considered by some experts to be one of the finest examples of mid-nineteenth-century landscape architecture in the state, the cemetery is situated on high land surrounded on three sides by streams. Since 1855, it has been the burial site of thousands of people, many famous and some unknown.

Oakdale was born in early 1852 at a meeting of prominent Wilmington businessmen who desired to establish a new burial ground outside the town limits. Dr. Armand J. DeRosset, a local physician, was elected the first president of the cemetery company. Ironically, the first burial at Oakdale took place on February 5, 1855, when Annie DeRosset, the doctor’s six-year-old daughter, was interred.

During the Victorian era, Oakdale was a popular place for Wilmington residents to socialize on weekends and holidays. To accommodate the crowds, two summer houses were constructed on the grounds in the 1870s. Streetcars ran to the cemetery every ten minutes in the early part of the twentieth century. By 1950, the original 65-acre cemetery site had grown to more than 128 acres.

The beauty of the cemetery is almost beyond description. At first sight, its layout appears to be the product of a Hollywood set designer rather than of dedicated city residents and mother nature herself. Breathtaking live oaks draped in Spanish moss thrive on the hilly terrain and create a cover of shade. Winding paths, old carriageways curving in graceful crescents, and narrow roads wind their way around hundreds of individual family plots. Stone steps inscribed with family names lead to the plots, most of which are bounded by low stone walls or iron fences with elaborate designs. Many sections are furnished with wire chairs and settees cast in iron, with fern and grapevine motifs.

The Victorian-era grave markers in a variety of shapes and sizes are of special interest. Located on the grounds are Egyptian obelisks, simple slabs, rustic logs with flower garlands, Gothic pinnacles, floral bouquets of stone, cast-iron crosses, and imposing Greek Revival mausoleums constructed of stone.

Each spring, the beauty of the cemetery is enhanced when thousands of flowers burst forth in bloom. Many of the plants that now beautify the grounds were planted by descendants of people buried in the cemetery long ago.

In many ways, Oakdale is a history book detailing the story of Wilmington since the mid-nineteenth century. Various sections of the cemetery exhibit the racial, ethnic, and religious heritage of the port city—for example, there is a Masonic section. Some of the finest ironwork in the cemetery is on the arched gate to the Hebrew section, opened on March 6, 1855, by the local Jewish community.

A large plot with few markers is the site where more than three hundred victims of the yellow-fever epidemic of 1862 were buried in unmarked graves. At the time, not one of the ten local physicians had even seen or treated the disease, and as a consequence, none of them could recognize the early symptoms: chills, headache, backache, and fever, followed by a flushed face, nausea, and vomiting. By the time the telltale signs of the disease—the jaundice, the stomach and intestinal hemorrhages, and the terrible “black vomit”—appeared, the doctors were virtually helpless.

Panic struck the city. Many wealthy residents fled upcountry by carriage and railroad, until most towns would no longer accept refugees from Wilmington. For those who could not leave or chose to remain, there was a month of horror to survive. John D. Bellamy, Jr., a future congressman, watched from the steps of his father’s mansion on Market Street as wagonloads of corpses were transported to Oakdale.

Throughout the ordeal, which ended in mid-November 1862 with an early cold snap, many stories of self-sacrifice and duty were written. Despite the exodus of many prominent citizens, the physicians and the clergy of Wilmington remained to minister to the suffering city. Dr. James H. Dickinson, one of the finest physicians of the Cape Fear area, spent every waking hour treating those afflicted with the disease. When he realized that he himself had contracted it, Dr. Dickinson wrote out instructions for his patients and returned to his own home to die. Father Thomas Murphy of St. Thomas the Apostle Church, the Reverend John L. Prichard of First Baptist Church, and the Reverend Robert B. Drane of St. James Episcopal Church tended the sick, provided Christian guidance, and worked tirelessly until each clergyman himself became a casualty of the epidemic. Dickinson, Prichard, and Drane are buried in the cemetery.

Of the many monuments gracing the grounds, the most impressive marks the burial site of 467 unknown men. Unveiled on May 10, 1872, the Confederate Memorial Monument consists of a tall bronze statue of a Confederate soldier on a marble and granite pedestal. Bronze likenesses of Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson are on the front and rear faces of the pedestal. Resting under the monument are the remains of Confederate soldiers who died at Fort Fisher in the waning days of the Confederacy.

Much of the fame of Oakdale Cemetery comes from the illustrious individuals buried here.

Perhaps the most famous woman interred in Oakdale is Rose O’Neal Greenhow, the talented, clever Confederate spy who was one of the few women to lose their lives in active service during the Civil War. Her grave is marked by a simple cross bearing the notation “a bearer of dispatches to the Confederacy.” Her body was brought to Wilmington after she drowned near Fort Fisher in September 1864 while attempting to avoid capture by Union forces.

Among the other famous Confederate heroes buried in the cemetery are Generals W. H. C. Whiting, Alexander MacRae, and John D. Barry; George Davis, the attorney general of the Confederacy; Captain John Newland Maffitt, naval hero; and Benjamin Beery, Confederate shipbuilder.

Also on the list of honored dead laid to rest in Oakdale are Edward B. Dudley, the first governor of North Carolina elected by popular vote, and Henry Bacon, Jr., the brilliant American architect.

Some graves of the not-so-famous have become noteworthy because of the intriguing stories behind the people buried in them.

A heartwarming tale surrounds a grave marker erected by the citizens of Wilmington in memory of a man and his best friend who gave their lives fighting a fire on February 11, 1880. Captain William A. Ellerbrook, a native of Hamburg, Germany, happened to be in town on that fateful day. When a cry went out along the waterfront for volunteers to assist in fighting a fire at a store at the corner of Front and Dock streets, Ellerbrook responded. From inside the blazing inferno, his cries for help could be heard. Recognizing his master’s call, the captain’s big Newfoundland dog raced into the burning building.

A day later, after the ruins cooled, the body of Ellerbrook was discovered pinned face-down to the floor by a rafter. Beside him was the body of Boss, his faithful dog. In the dog’s mouth was a portion of Ellerbrook’s coat, which Boss had torn away while attempting to pull his master to safety.

So moved were the citizens of Wilmington by the heroism of the twenty-four-year-old sea captain and his pet that they donated funds to erect a monument in Oakwood Cemetery, where the two were buried together. On one side of the marker are the details of Ellerbrook’s life. On the other is a design of a sleeping dog with the words Faithful Unto Death.

Oakdale Cemetery is open daily to the public. Information on specific grave sites and a free brochure giving directions to numbered plots are available at the office, located at the entrance gate.

Return to the intersection of Fifteenth and Market, turn right, and drive west to New Hanover High School, at 1307 Market. Rising two stories over a full basement, the enormous sand-colored building is one of the few structures in the city with an exterior of glazed tile. Construction of the central block was completed in 1922. The two wings were added three years later.

Several Wilmingtonians who have achieved national and international fame in the second half of the twentieth century attended this school.

David Brinkley, the beloved NBC and ABC television journalist and author, was a student here. Born in 1920 in a two-story frame house at the corner of Eighth and Princess streets, he began his career in journalism as a reporter with the local daily newspaper.

Robert Ruark, the noted newspaperman, novelist, and world traveler, also graduated from New Hanover High. Born in Wilmington in 1915, Ruark used his experiences as a child on the Cape Fear as the basis for three of his most famous novels: The Old Man and the Boy (1957), Poor No More (1959), and The Old Mans Boy Grows Older (1961).

Two former superstar quarterbacks of the National Football League, Sonny Jurgensen and Roman Gabriel, began their stellar athletic careers at New Hanover High School.

Continue west on Market Street to the Cape Fear Museum, formerly the New Hanover County Museum of History, located at 814 Market. Since April 1970, the museum has been housed at the present location, but its roots go back to 1897, making it the oldest local-history museum in the state. It was founded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy “to collect and preserve relics and objects of local value … relating to the recent war.”

The collection was originally assembled and displayed in the John A. Taylor House (Wilmington Light Infantry Building), located farther west on Market Street. Over the years, the holdings were transferred to Raleigh, where they remained until 1925, when the museum was reestablished in the New Hanover County Courthouse on North Third Street.

The present museum building, built in a modified late Gothic Revival style, was constructed as an armory in the mid-1930s by the Public Works Administration. After its acquisition for use as a museum, the expansive brick building was extensively renovated. Numerous additions and modifications have since taken place. Neatly displayed throughout the multilevel exhibition area, the eclectic collection chronicles the cultural and natural history of Wilmington and the surrounding area.

Wilmington was born of a crude settlement that took root on a high bluff on the Cape Fear River in 1732. A year earlier, John Maultsbury had received a grant of 640 acres at the fork of the river, on which he began a village, New Liverpool. About the same time, John Watson obtained a patent for adjoining lands from Governor George Burrington. James Wimble, a Boston mariner, was employed to lay out a town on Watson’s grant. By 1733, he was selling lots in the town he called Carthage.

As the community grew, its name was changed to Newton. Its quick rise in stature was accentuated when Governor Gabriel Johnston ordered the county government and court to meet in Newton in 1735.

Legislation was introduced in 1739 to establish the town of Wilmington at the site of Newton. Governor Johnston selected the new name to exalt his patron, Spencer Compton, the earl of Wilmington. In February 1740, the colonial assembly passed an act that incorporated the town of Wilmington and made it the county seat of New Hanover County.

A variety of factors combined to make Wilmington the most important port in the colony soon after it was chartered. Its fine harbor was located upstream from the storms and the pirates of the Atlantic. Of equal importance were the vast forests of virgin pine encircling the town. From these forests came tar, pitch, turpentine, and similar products which were badly needed by Britain and other European powers. From 1720 to 1870, North Carolina led the world in the production of naval stores, and Wilmington was the primary center for their export. Museum exhibits showcase the naval-stores industry.

Wilmington was mostly spared the hostilities of the Revolutionary War until early 1781. Prior to that time, the closest fighting was 20 miles to the north at Moores Creek Bridge.

On April 12, 1781, the battered, demoralized army of Lord Cornwallis straggled into Wilmington after its costly “victory” over the American forces of General Nathanael Greene at Guilford Courthouse. For almost two weeks, the British army rested and took on supplies at Wilmington. Then, on April 25, Cornwallis began his fateful journey north to Yorktown, Virginia.

A fleet horse carrying famous cavalry officer Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee galloped into Wilmington on November 17, 1781, bearing the jubilant news of the surrender of Cornwallis.

Of all the museum’s holdings, the most impressive is the collection of artifacts related to Civil War history. Many of the items were acquired in 1983 from the defunct Blockade Runner Museum at Carolina Beach. Included in the acquisition were two large dioramas—one of Fort Fisher and the other of the Wilmington waterfront during its days of critical importance to the Confederacy.

In the annals of the Civil War, the names of certain Southern cities appear over and over again. By 1864, Wilmington, North Carolina, had become the most important city in the entire South, with the possible exception of the Confederate capital of Richmond.

No sooner had the rumblings of war commenced in early 1861 than Wilmington began its rise to prominence as an industrial center, a supply depot, the chief port of the blockade runners, and “the lifeline of the Confederacy.” Over the next four years, the armies of the Confederacy were fed, clothed, and equipped thanks to goods delivered to Wilmington by sleek vessels that had eluded the Federal blockade along the North Carolina coast.

By the second half of 1864, Wilmington was the last major Southern port open to the Confederacy. Just a month after Fort Fisher fell to Union forces in January 1865, Wilmington was abandoned to the approaching blue-clad soldiers. As a result, the fate of the Southern war effort was sealed.

Among the most popular museum exhibits are the displays of memorabilia from hometown sports legends. Exhibited are a number of items that once belonged to favorite son Michael Jordan, the man many observers consider the greatest basketball player ever.

From the museum, proceed west on Market Street toward the waterfront. This route will take you into the heart of the Wilmington Historic District. In a speech before the Historic Wilmington Foundation in November 1975, David Brinkley told his audience, “I’m on the Board of Trustees at Colonial Williamsburg, which is really only a big restoration project…. It may be a startling fact, but true, that Wilmington has a greater number of interesting houses than Williamsburg does.”

Indeed, Wilmington possesses residential, commercial, and governmental buildings that are the envy of the other historic cities of the Atlantic coast. Bounded by Ninth Street on the east, the Cape Fear River on the west, Harnett Street on the north, and Wright Street on the south, the two-hundred-block Wilmington Historic District has been entered on the National Register of Historic Places. Encompassing the oldest part of the city, it contains buildings dating from the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Within the district are structures representing every major architectural style used in the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

In 1757, a visitor named Peter DuBois provided a glowing account of the city, noting that “the Regularity of the Streets are equal to those of Philadelphia and Buildings in General very good. Many of Brick, two or three stories high with double piazzas which make a good appearance.”

Laid out in a style popular in Europe throughout the eighteenth century, the Wilmington grid plan was established in 1739 and modified in 1743. It remains virtually intact. With the exception of Water and Front streets, the north-south streets are designated by numbers. The named streets begin at the river and run east.

A leisurely walk or slow drive along these ancient streets allows visitors to savor the history and architectural heritage of the city. Some of these ancient thoroughfares seem too narrow to allow two lanes of traffic. Paradoxically, others nearby are extremely wide, giving the impression that they were constructed in the modern age to handle vehicular traffic. Three boulevards—Market Street, Third Street, and Fifth Street—measure ninety-nine feet in width, instead of the sixty-six standard for streets. Market and Fifth are decorated with landscaped center plazas and curbside greenery. Some city streets are still paved with brick.

Follow Market Street to St. Paul’s Evangelical Lutheran Church, located 2 blocks from the museum at 603 Market. On September 6, 1859, the cornerstone of this handsome Gothic Revival structure was laid by the local German community. Construction was not completed until 1869, and the brick exterior was stuccoed four years later. This church’s most striking architectural feature is the square central tower, from which rise four pinnacles and a small spire topped with a cross.

Continue west to the William Jones Price House, at 514 Market.

Wilmington has its share of ghost stories, and one of the most interesting has to do with this two-story brick dwelling, built in the Italianate style in 1855 for a local physician. Before the house was built, the eastern boundary line of the city ran along what is now Fifth Street. The lot on which the house was constructed was situated at the top of a bluff overlooking the city. Known as Gallows Hill, the bluff had previously been the place where criminals were executed. After each execution, if the victim’s body was not claimed, it was buried at the site. Legend holds that the unclaimed souls continue to roam the property.

Tales of strange happenings and wandering spirits came from members of Dr. Price’s family as soon as they moved in. In the basement, where the physician maintained his offices, and in the twelve large rooms of the upper floors, eerie sounds were heard in the dead of night. Sometimes, after every family member was safely tucked in bed, doors opened and closed. Footsteps were heard on the elegant staircase. The sound of metal on metal emanated from the house.

In 1934, the Gause family came into possession of the property. The reports of the hauntings continued. Experts on the supernatural have been unable to explain the mystery after spending night after night in the house. In recent years, several old brick tombs containing the bones of unknown criminals have been unearthed by workmen laying pipe in the backyard. Some believe that the unexplained occurrences are the work of the condemned men, who are said to be seeking peace.

From the William Jones Price House, proceed to the Bellamy Mansion, located in the same block on the northeastern corner of Market and Fifth streets.

The Bellamy Mansion is one of the last great antebellum houses built in America. Noted architect James F. Post was assisted by Connecticut draftsman Rufus Bunnell in the creation of the splendid twenty-two-room wooden castle, constructed between 1857 and 1859 for Dr. John Dillard Bellamy and family. An ardent supporter of the Confederate cause, Dr. Bellamy allowed Southern soldiers to use the cupola as an observation post throughout the war. When Wilmington fell under Federal control in February 1865, the mansion was used as the headquarters of Union general Joseph Hawley, a native of North Carolina. Accordingly, many slaves were granted their freedom on the steps of the house.

As early as 1903, the magnificent structure made its appearance on postcards of the city. Later, it was featured in several books and magazines on architecture.

Ellen Douglas Bellamy, one of Dr. Bellamy’s daughters, was the last member of the family to live in the mansion. At her death in 1946, the house was inherited by more than fifty relatives. Years passed while the heirs debated what should be done with the house.

In 1971, a potentially destructive fire of suspicious origin spurred the owners to action. Although the fire did only $6,000 worth of damage to the structure, more than $70,000 in antique furnishings were lost. Consequently, in 1972, the heirs formed a nonprofit foundation—Bellamy Mansion, Inc.—to fund the preservation of the house. From 1972 to 1990, the foundation pumped more than $240,000 into the restoration project.

On a cold, windy December afternoon in 1989, more than fifteen hundred people waited in a line that stretched a couple of blocks down Market Street to see the mansion, which was being opened to the public for one day only. It was the first time the mansion had been opened in many years.

Encouraged by the public’s interest, and satisfied that the house could be saved for future generations, the Bellamy family donated the mansion and grounds to the Historic Preservation Foundation of North Carolina, Inc. Now operated as the Bellamy Mansion Museum of History and Design Arts, the house celebrated its grand opening in April 1994.

Even though the restoration project continues, the museum offers exhibits related to preservation, decorative arts, regional architecture, and landscape architecture. A glassed-in portion of an unrestored interior wall is used to illustrate the damage sustained in the fire of 1971.

This structure has been unashamedly known as a mansion ever since it was built. Probably the most visually impressive house in the city, the Bellamy Mansion deserves its title. Regarded as an architectural maverick, the enormous white palace is a combination of Greek Revival, Italianate, and Classical Revival styles. The imposing multi-story masterpiece rests on a raised basement. The two-story porch wrapping around three sides of the house features fourteen massive Corinthian columns. Atop the tall, pedimented gable roof rests the ornately decorated cupola.

The mansion’s appearance is enhanced by its location on a large corner lot. Giant magnolias and tropical plants grace the front and side yards, which are enclosed by an elaborate cast-iron fence. Several outbuildings, including a two-story slave quarters, a privy, a cistern, and a dairy cooling room, survive in the rear corner of the lot.

Before leaving Market and Fifth, take a moment to enjoy the Kenan Fountain, unmistakable in the center of the intersection.

Wilmington has earned its place as one of the nation’s most historic cities. Its citizens have honored significant local events and people with a variety of markers and monuments. Although modern traffic engineers have reduced it in size and splendor, the Kenan Fountain remains one of the most significant monuments of the city.

Erected in 1921, the fountain was given by native son William Rand Kenan, Jr., to beautify the city and to honor his parents. Carrere and Hastings, the firm with such credits as the New York Public Library, the United States Senate Office Building, and the old United States House of Representatives Building, designed and sculpted this majestic fountain in New York. It was erected there, dismantled, and then shipped to Wilmington in more than thirty boxcars.

Water is sprayed from a limestone bowl and splashes into a circular pool. Secondary fountains featuring sculpted turtles and fish are situated around the pool.

In 1953, a street-level section of the fountain was removed following a recommendation by state highway engineers that the entire intersection be cleared “in the interest of public safety.”

William Rand Kenan, Jr., the donor of the fountain, was born in Wilmington in 1872 to parents whose families had already left their imprint on the history of the state. He descended from the famous Kenan family of nearby Kenansville and the Hargrave family, who provided the land on which the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill was built.

In 1894, Kenan graduated from that school—an institution which would thereafter benefit substantially from his affluence. In Chapel Hill, he gained worldwide attention for his discovery of calcium carbide, the basis for the manufacture of acetylene. From that discovery emerged the Union Carbide Company. As a principal in the company, Kenan made important connections with America’s wealthiest industrialists.

His scientific genius caught the attention of Henry Morrison Flagler, a partner of John Rockefeller in the Standard Oil Company. At the time, Flagler was beginning to develop the eastern coast of Florida. He secured Kenan’s services as a consultant over all of his Florida enterprises, which included railroads and a chain of resort hotels. In 1901, Flagler married Kenan’s sister, Mary Lily, further cementing the relationship between the two men.

Drive west to the 400 block of Market.

Constructed between 1859 and 1870, First Baptist Church, at 421 Market, is little changed from the plans drawn by Samuel Sloan, who later designed the Governor’s Mansion in Raleigh. Inside the massive brick sanctuary, the original pews, galleries, and other wooden features—all constructed of heart of pine—survive. Of the exterior architectural features, the most interesting are the double towers, one at either end of the facade. The eastern tower is the taller, stretching 197 feet above the street. At the time it was completed, the tower was the tallest church spire in the United States.

Constructed in 1847 as the residence of a local businessman and ferry operator, the John A. Taylor House (Wilmington Light Infantry Building), at 409–411 Market, is an unusual Classical Revival structure that has been used for a variety of purposes. This sturdy, two-story, pressed-brick building has a marble-veneer exterior. In 1892, it was acquired by the Wilmington Light Infantry and used as an armory until 1951. Wilmington Light Infantry members placed the existing cannon atop the corner of the roof parapet. The building was later used for a time as the public library.

The Harnett Obelisk, set in the center of Market Street just before the intersection with Fourth Street, memorializes Cornelius Harnett, Jr., and the other Cape Fear patriots who offered the first armed resistance to the Stamp Act in the American colonies. From the bottom of the marble base to the tip of the obelisk, the monument rises thirty feet. Its cornerstone was laid in mid-1906.

At the intersection of Market and Fourth streets, turn right on Fourth and drive north to the intersection with Red Cross Street. Turn left on Red Cross and proceed west 4 blocks to the junction with Water Street on the Wilmington waterfront. Turn left on Water Street and park in the on-street spaces just south of the Wilmington Railroad Museum to begin a walking tour of the downtown area.

Located at 501 Nutt Street, near the intersection of Water and Red Cross, the Wilmington Railroad Museum pays homage to an industry that has been an integral part of the city since the first half of the nineteenth century.

In 1835, a meeting of the most influential businessmen of the city at the home of future governor Edward B. Dudley resulted in a revolutionary innovation in the local transportation system: the railroad. Construction of the Wilmington and Raleigh Railroad commenced a year later. However, the failure of Raleigh interests to raise their construction obligations caused the rails to be rerouted to Weldon, near the North Carolina-Virginia border. After four years of arduous labor, the final spike of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad was driven near Goldsboro on March 7, 1840, completing the 161.5-mile track. At that time, the track was the longest in the world.

During the Civil War, the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad was of extreme importance to the Confederate war effort. Weapons, shoes, clothing, and food from the blockade runners at Wilmington were hastily transported via the railroad to the battlefields of Virginia. So vital was the railroad that it was known the world over as “the Lifeline of the Confederacy.”

In 1902, the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad, the successor of the Wilmington and Weldon, selected Wilmington as its home office. Until December 10, 1955, when the announcement was made that the general offices of the Atlantic Coast Line would be moved to Jacksonville, Florida—a day still known to many older Wilmingtonians as “Black Thursday”—the railroad shops and buildings dominated waterfront activity. At the time of the unwelcome announcement, the railroad employed 1,350 people locally, and its annual payroll constituted 10 percent of the income in the city.

In the late 1970s, a group of former railroad employees and train buffs, concerned that Wilmington was about to lose a significant part of its history, formulated plans for a museum. Since it opened in 1984, the Wilmington Railroad Museum has been housed in one of the few surviving buildings from the great railroad empire that once flourished here.

Before entering the brick building, visitors are at liberty to examine the steam engine and bright red caboose on the grounds. Inside the museum, the exhibits transport patrons back to the era of the passenger railroad. Among the interesting artifacts displayed are a four-ounce conductor’s timepiece, a bar of soap from a Pullman car, and station equipment. Historic photographs line the walls, and model trains fascinate young and old alike.

Adjacent to the museum, the Downtown Area Revitalization Effort has developed the Coast Line Convention Center, a $7-million complex of lodging, dining, meeting, and shopping facilities. Housed in the complex is the Greater Wilmington Chamber of Commerce, thought to be the oldest organization of its kind in the state.

From the museum and convention center, walk south on Water Street.

In accordance with the original town plan, the street on the waterfront was named Front Street, rather than taking its place among the numerically named streets running parallel to the river. A new street named Water Street, located closer to the water, was authorized by the legislature in 1785. Thus, Water Street became the scene of the waterfront activity that has made Wilmington a business and industrial giant for more than two centuries.

Stop at the United States Coast Guard Docks, located 3 blocks from the museum at the foot of Princess Street. Visiting military ships from foreign countries frequently tie up here. Public tours of the vessels are sometimes available.

Just beyond the United States Coast Guard Docks is Riverfront Park. Here, visitors can stand where busy piers and wharves were once located and enjoy the salty flavor of the port city. Just across the river, the once-potent guns of the Battleship North Carolina seem to be turned on Wilmington.

This municipal park offers a scenic vista of the Cape Fear River, the very essence of the old city. Although Wilmington is nearly 30 miles upriver from the mouth, the deep Cape Fear has made it an important port of call for ships from all over the world since the middle of the eighteenth century.

From the park, visitors can gaze south down the river to see the Cape Fear Memorial Bridge. When this engineering marvel was completed in October 1969, it was the first lift-span bridge in the state.

Of the many interesting architectural features embodied in the bridge, the 408-foot lift span is the most spectacular. In elevator-like fashion, the span is raised and lowered to allow large ships to clear the bridge. Two enormous support towers rise 200 feet above the river.

A mind-boggling list of materials—including 82,500 pounds of wire rope and cable, 258 railroad cars full of concrete, and 3,000,000 pounds of reinforced steel—were used in the bridge’s construction.

Park visitors who wish to see more of the town via the river can use either of two tour vessels that dock on the river at the park.

The Captain J. N. Maffitt, a fifty-four-foot World War II launch, operates as a river taxi between Wilmington and the Battleship North Carolina. Named for John Newland Maffitt—a Wilmingtonian who acquired the title “Sea Devil of the Confederacy” for his exploits as an officer in the Confederate navy—the boat treats passengers to a panorama of the historic city.

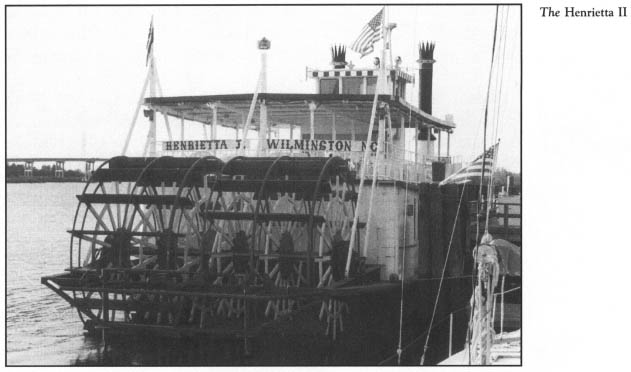

On a much grander scale, the Henrietta II offers narrated dinner cruises on the river. When Wilmington native Carl Mashburn brought his new, eighty-six-foot boat to the port city in 1988, the vessel earned the distinction of being the only true stern wheeler in the state. The original Henrietta, this ship’s namesake, was constructed in 1818 at Fayetteville. The first steam-boat built on the Cape Fear, it made regular trips between Wilmington and Fayetteville for forty years.

Towering above Riverfront Park on the eastern side of Water Street is the massive Alton F. Lennon Federal Building. On December 9, 1916, the cornerstone was laid for this magnificent stone edifice. Designed to house the United States Customs Office, this stately, three-story Neoclassical Revival structure has dominated the Wilmington waterfront since its completion. Few cities of comparable size in the nation can boast such an imposing federal structure.

James Wetmore, architect of the United States Treasury Building in Washington, D.C., is credited with the design of the building. Rising from an enormous stone base, the central block is adorned with Doric pilasters and engaged columns. Projecting wings on either side add balance to the block, which is capped by a stone balustrade.

Continue 3 blocks south on Water Street to Chandler’s Wharf, at the foot of Ann Street. Developed in the 1970s on a site where wharves and warehouses stood in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, this five-acre shopping and dining complex features a cluster of restored buildings in a shady waterfront setting, along with an elegant warehouse mall across the street. Cobblestone streets and nautical antiques spread about the grounds lend a maritime atmosphere. Of special interest on the waterfront is the tugboat John Taxis, thought to be the oldest in the United States.

Proceed east for 1 block on Ann Street to its intersection with South Front. Turn right and walk south along the 300 block of South Front. Of the half-dozen or so houses in this block built prior to the Civil War, the Wells-Brown-Lord House, at 300 South Front, is the oldest. Constructed in 1773, the tall, two-story frame dwelling rests on a high bluff overlooking the river.

Cross Nun Street to see the Governor Dudley Mansion, at 400 South Front.

Of the numerous mansions gracing the streets of the Wilmington Historic District, this elegant showplace is the oldest and one of the most beautiful. Constructed around 1825 by Edward B. Dudley, governor of North Carolina and the first president of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad, the Federal-style mansion was subsequently renovated and enlarged after being damaged by two fires.

Dudley made the house a center for social and political activities. Subsequent owners, including socialite Pembroke Jones, maintained the tradition. As a consequence, the house has hosted more notable people than any other residence in the city. In 1844, during his presidential campaign, Henry Clay stayed in the mansion. Four years later, Daniel Webster was entertained here. Future Union general William T. Sherman attended the wedding of Governor Dudley’s daughter in the mansion’s dining room. Mr. and Mrs. Pembroke Jones welcomed Cardinal Gibbons and twelve bishops to the mansion in January 1890. Woodrow Wilson, then a professor at Princeton, visited the house in January 1901, while historian James Sprunt owned the mansion. President William Taft breakfasted with Sprunt on his visit to Wilmington that same year. Included in the Taft party was Captain Archibald Butt, who later had the dubious distinction of being the only North Carolinian to die aboard the Titanic. When he came to Wilmington to lecture at Thalian Hall, William Jennings Bryan was feted at the Governor Dudley Mansion by Sprunt.

The brick house originally consisted of just the two-story main block. Flanking recessed wings were subsequently added. After he acquired the house in 1895, James Sprunt put a second story on the wings and enclosed the property with the existing brick walls. The tall palm trees growing on the grounds were planted a year later.

At the intersection of South Front and Nun streets, turn east along the 100 block of Nun. There is a fine ensemble of houses, many built in the second half of the nineteenth century, in this block. Of particular interest is the William Rand Kenan House, at 110 Nun. Built in the Italianate style in 1870, the house was the birthplace of William Rand Kenan, Jr., and his siblings. Its present Neoclassical appearance dates from renovations in 1910.

Across the street from the William Rand Kenan House, the 1910-vintage dwelling at 117 Nun was the boyhood home of author Robert Ruark.

After 1 block on Nun, turn left onto South Second Street and walk north along the 300 block of South Second. Here, a trio of houses—the Louis Poisson House at 308 South Second, built around 1886; the McRae-Beery House at 303 South Second, built around 1850; and the Walker-Cowan House at 302 South Second, built around 1869—display the classic Italianate style that dominated Wilmington residential architecture throughout much of the nineteenth century.

At the intersection of South Second and Ann streets, turn left and walk west 1 block on Ann. Turn right on South Front and proceed 1 block north to Orange Street. Turn right onto the 100 block of Orange.

Located at 102 Orange, the Smith-Anderson House is thought to be the oldest structure in the city. Erected in 1740, the dignified two-and-a-half-story building stands directly on the sidewalk of an avenue that was nothing more than a narrow, unpaved path when the house was built. Constructed in the Georgian style, the imposing house has been modified on several occasions.

The St. John’s Museum of Art is located at 114 Orange in a complex of historic structures that includes the former St. John’s Masonic Lodge (1804), the Cowan House (1830), and the former St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church. The museum opened its doors on April 5, 1962. Since that time, it has earned a reputation as an outstanding regional art museum.

Its permanent collection is housed in the former St. John’s Masonic Lodge, one of the most historic landmarks in the city. Constructed as the first permanent home of St. John’s Lodge No. 1, the oldest Masonic lodge in the state, it exhibits a Georgian style, even though it dates from the Federal era.

St. John’s was one of the few buildings south of Market Street that survived the disastrous fire of November 4, 1819, which destroyed over three hundred buildings in downtown Wilmington. Members of the lodge were able to salvage their meeting house by covering it with wet blankets. They managed to keep the blankets saturated with water from a bucket brigade of members stretching in a long line all the way to the river.

A need for larger quarters led to the relocation of St. John’s Lodge to Front Street in 1824. Thomas Brown, a prominent local jeweler, thereafter purchased the property for use as his personal residence. It remained in his family until 1943. Frame additions to the original brick structure were in place before 1849.

James H. McKoy acquired the house in 1943 and converted it into a popular restaurant, St. John’s Tavern. For the duration of World War II, the eating establishment proved a favorite of the multitude of armed-services personnel stationed in the area. Following the war, its reputation spread far and wide. By the time it closed in 1955, the tavern had a reservation book that read like a who’s who of world-famous personages.

Some of the original English locks and hinges are evident on the doors of the old lodge building. The lamp beside the entrance steps is the only survivor of the first electric streetlights installed in the city in 1886.

On the interior, a map entitled “Plan of the Town of Wilmington” graces the eastern wall. Reproduced from the original drawn in 1810 by J. J. Belanger, a French cartographer, the map depicts the old section of the city and details the nine public buildings in existence when St. John’s was erected. Today, only St. John’s survives.

The museum maintains the Hughes Gallery at the former St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church. Twelve diverse temporary exhibitions are held in this gallery each year.

Art classes, workshops, and other educational programs are conducted in the Cowan House.

The museum’s ever-expanding collection features two centuries of North Carolina art. By far the most significant acquisition to date took place in 1984, when the museum received a bequest of a set of original color prints by nine-teenth-century American artist Mary Cassatt, who worked with the Impressionist masters of France. Fewer than ten such sets exist in the entire world.

After 1 block on Orange, turn left onto South Second and walk north for 2 blocks.

Located at 23 South Second, the DeRosset House ranks with the Bellamy Mansion as the two finest antebellum homes in the city. The beauty of this enormous, five-bay, two-story frame mansion is heightened by its splendid setting on a brick-terraced hill overlooking the river.

Built in 1841 by Dr. A. J. DeRosset III, the house exhibits a Greek Revival portico supported by fluted Doric columns. Two significant changes were later made to the house. In 1874, the Italianate cornice and the tall cupola, reminiscent of an Italian bell tower, were added. Only three such cupolas exist in the city today. At the same time, an ell was attached to the rear and an enclosed porch was added on the Dock Street side. To enlarge the house, the ell was extended to Dock Street in 1914.

At the intersection of Second and Market, turn right and walk east 1 block on Market.

One of the few historic houses in Wilmington that is open to the public, the Burgwin-Wright House, at 224 Market, affords an opportunity for visitors to appreciate the wealth and prestige of John Burgwin, who built the beautiful house in 1770.

Constructed on the massive stone walls of an old jail that appeared on the Sauthier map of 1769, the two-story frame structure is the most opulent of the few remaining Georgian-style houses in the city. Its most prominent exterior features are its double piazzas, front and back, covered by the overlapping roof. Ionic columns support the porch canopy.

Of special interest is the detached three-story kitchen. Separating the kitchen from the main house is a courtyard surrounded by well-landscaped grounds and a magnificent garden. The garden plan is characteristic of eighteenth-century English gardens. Enormous magnolia trees shade the front lawn.

John Burgwin, an unrepentant Tory who served as colonial treasurer under Royal Governor Arthur Dobbs, found it necessary for his personal safety to flee to England at the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. He remained there until the hostilities ended. In Burgwin’s absence, Lord Cornwallis and his staff occupied the house for two weeks in 1781. The house’s original floorboards display marks made by British muskets.

An intriguing story that unfolded more than two hundred years ago surrounds the stately house. Before his arrival in Wilmington, one of the young officers on Cornwallis’s staff was smitten by a young lady in South Carolina. While sequestered at the Burgwin-Wright House, this officer used his diamond ring to etch his true love’s name in a windowpane. The war soon ended, enabling him to return to South Carolina. There, he married the woman of his dreams and took her to England.

Several years later, the young couple sailed to America and took up residence in New York. In 1836, the couple’s son visited Wilmington as the guest of Dr. Thomas H. Wright, who had inherited the house. As fate would have it, the visitor was quartered in the bedroom occupied by his father almost a half-century earlier. He noticed the etched pane of glass and at once recognized the name as his mother’s.

Forty years later, John W. Barrow, the grandson of the British officer, having been told the story of the windowpane by his father, came to Wilmington in search of it. Calling at the Burgwin-Wright House, he learned from the owner that the house had been remodeled. Barrow and the owner descended to the cellar, where prisoners had once been confined during wartime. There, they found the special pane, which had been put in storage after the renovations. Barrow returned to his home with the prize in his possession.

Every day, thousands of drivers and pedestrians travel the streets and sidewalks of Wilmington without realizing that a mysterious labyrinth of tunnels lies beneath them. Throughout the twentieth century, workmen demolishing buildings and digging utility lines have unearthed ancient, bricked-over tunnels in various parts of downtown. At least four distinct passageways—one of which is evidenced by a bricked-over opening in the northwestern wall of the cellar of the Burgwin-Wright House—are known to exist. This tunnel leads to a second tunnel that connects with the Jacob’s Run tunnel, the most famous of the passageways.

While clearing a site at the northeastern corner of Second and Market streets for a construction project in 1958, workers unwittingly smashed a hole in the top of the Jacob’s Run tunnel. An examination of the arched passageway disclosed that it ran with the flowing waters of Jacob’s Run, an underground stream which originates at springs near the intersection of Fourth and Princess streets and flows west to the Cape Fear. Wooden flooring covers the stream in the tunnel to allow human passage. Constructed of handmade bricks of various sizes, the tunnel measures two feet in width and six and a half feet in height.

Although the origin and initial purpose of the subterranean passages remain a mystery, several explanations have been posited. In colonial times, dark, damp passageways were used to store and cure hides. A more plausible explanation is that the tunnels were escape routes for early citizens of the town, who lived under constant threat of Spanish privateers. Legend has it that during the Revolutionary War, secret passageways allowed American prisoners to escape from the British jail in the subbasement of the Burgwin-Wright House.

Just beyond the Burgwin-Wright House, the George Davis Statue stands in Market Street at its intersection with Third. Erected to memorialize the native son who served as senator and attorney general of the Confederate States of America, the handsome statue depicts Davis with an arm outstretched toward the west. Sculpted by F. H. Packer, it was dedicated on April 20, 1911. In late 1987, the statue was restored to its original beauty by Van Der Stock, an internationally known sculptor from Holland. Fittingly, the northwestern corner of the intersection where the statue stands was the site of the local Confederate headquarters, the nerve center of the “Lifeline of the Confederacy.”

Turn right on South Third. Located at 1 South Third, St. James Episcopal Church stands proudly as the oldest church in continuous use in the city. It is actually the second church building constructed by the local Episcopal congregation. Construction of the first church was authorized in 1751, and work commenced on the simple brick building on Fourth Street in 1753. Funds for the construction came from goods recovered when an invading Spanish privateer was sunk in the Cape Fear downriver, near Brunswick Town. One treasure salvaged from the ship—a painting of Christ entitled Ecce Homo, “Behold the Man”—hangs in the vestry of the existing church.

Nationally known architect Thomas U. Walter, who later gained fame when he designed the cast-iron dome of the United States Capitol, drew the plans for the existing St. James edifice. Its cornerstone was laid in 1839. The most distinctive architectural feature of the Gothic Revival building is its square entrance tower. Accented with octagonal pinnacles at its corners, the bell-and-clock tower rises through the body of the building. Every year since the end of the Civil War, an Easter sunrise service has been conducted from atop the tower.

The Reverend Alfred A. Watson was rector in January 1865. At the height of the second battle at Fort Fisher, amid the sounds of the ferocious bombardment by the Federal fleet, Watson led the Episcopal congregation in a prayer of intercession: “From battle and murder, and from sudden death, Good Lord deliver us.”

A month later, upon the surrender of the city to the Union army, Watson was ordered to include the president of the United States in his prayers. He resolutely refused. His open defiance apparently infuriated the invaders, because the 104th Ohio Volunteers halted church services on February 26 and seized the church. After they removed the pews, the Union troops converted the church building into a hospital.

Included among the parade of important houses on South Third Street is a rare residential unit designed by hometown hero Henry Bacon, Jr., architect of the Lincoln Memorial. Located at 15 South Third, the Donald MacRae House represents one of only four residential designs ever drawn by Bacon. Despite its designer’s apparent lack of interest in residential architecture, this 1901-vintage dwelling is tangible evidence of the Bacon genius. It is a splendid example of the shingle-style house that became popular in the city in the early part of the twentieth century.

Wilmington and Raleigh are the only cities in North Carolina that possess monuments designed by Bacon. Located in the plaza at South Third and Dock streets, the Confederate Memorial is another of Bacon’s hometown masterpieces. He collaborated with sculptor F. H. Packer to produce this monument. Bacon died before it was unveiled in 1924. Set atop the granite pedestal and silhouetted against the fifteen-ton shaft are two bronze soldiers, one representing courage and the other sacrifice.

Continue south to the 100 block of South Third.

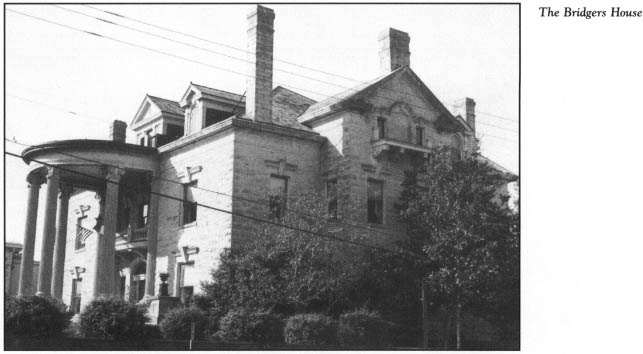

Of the mansions built in the city in the first decade of the twentieth century, the most spectacular is the Bridgers House, at 100 South Third. Constructed in 1905, this monumental Neoclassical Revival structure was for many years the pride of Elizabeth Eagles Haywood Bridgers. Mrs. Bridgers came from a family long distinguished in local, state, and national history. Her father-in-law, Rufus Bridgers, was a nationally known official of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. Her grandfather John Haywood was the treasurer of the state of North Carolina. Mrs. Bridgers was also a descendant of Richard Eagles, the man for whom nearby Eagles Island—the site of the Battleship North Carolina—was named.

Majestically situated at the top of a hill rising from the river, the two-and-a-half-story structure is constructed of stone quarried in Indiana and shaped in South Carolina. It features a magnificent semicircular portico buttressed by tall Ionic columns.

Nearby at 114 South Third is the Savage-Bacon House, constructed in 1850 as a bracketed and vented Italianate dwelling. Its Neoclassical appearance dates from renovations in 1909. This house is best known for its residents from 1891 to 1899: noted engineer Henry Bacon, Sr., and his family, including sons Henry Jr., the future architect, and Francis, the future archaeologist and furniture designer of national fame.

Among the great churches of Wilmington, First Presbyterian Church, at 121 South Third, has the youngest building. Construction of the late Gothic Revival sanctuary began in December 1926. Designed by noted church architect Hobart Upjohn, the limestone-trimmed building is covered with a gable-roofed basilica and a square, four-story tower from which rises a stone spire. Elegantly designed stained-glass windows punctuate the sanctuary walls. Above the altar is a beautiful rose window.

Among the famous ministers who have preached in the present sanctuary was Peter Marshall, who stood in the pulpit in 1939 and 1940.

Located just north of the sanctuary, the small stone chapel is of Norman and Gothic design. Located to the rear, the educational building was designed in the Tudor style by architect H. L. Cain. All of the handsome buildings blend harmoniously to form a spectacular architectural portrait.

Fire destroyed three sanctuary buildings that preceded the existing church. It was in the third building that the Reverend Joseph R. Wilson preached. He served as minister of the church from November 1, 1874, to April 1, 1885. A splendid memorial plaque honoring the Reverend Wilson’s famous son, Tommy, was dedicated in the narthex of the current sanctuary in 1928.

A teenager when he lived in the city, Tommy Wilson spent many hours on the river swimming, watching ships, and chatting with sailors from distant ports. He played shortstop on a local baseball team. He also owned the city’s first high-wheel bicycle, a gift purchased by his father to help Tommy gain strength after a digestive disorder.

In preparation for college, Tommy was tutored in Greek and Latin by Mrs. Joseph R. Russell, an outstanding local teacher. She could see that her bright pupil was destined for greatness. His intense interest in government caused her to remark to him on one occasion, “Someday, you are going to be president of the United States.”

Soon thereafter, he departed for college, where he dropped the name “Tommy.” Although Mrs. Russell died long before her prophetic remark came true, Thomas Woodrow Wilson was elected to two terms as president of the United States.

The Zebulon Latimer House is located at 126 South Third. Zebulon Latimer, the man who constructed this graceful house, was a prosperous Wilmington merchant who migrated to the city in the 1830s from Connecticut. Not only is this stuccoed masonry home an outstanding example of the affluent architecture of the antebellum period, but it also represents a subtle variation on the Italianate style so popular in the city. It is much more ornamented than other houses of the same period.

Built in 1852, the house remained in the Latimer family until 1963, when the Lower Cape Fear Historical Society purchased the property and the home’s elegant furnishings. Meticulously restored and furnished, the grand house is open to the public.

Of special interest in the yard of the Zebulon Latimer House is a three-tier cast-iron fountain that was moved from the street plaza when South Third was widened to accommodate modern traffic.

Continue across Orange Street to the 200 block of South Third, where you will see another piece of “street furniture” in the plaza of South Third. This combination cast-iron water fountain and watering trough was installed in the 1880s as part of a beautification project in the city.

At the intersection of South Third and Ann, turn left and walk east on Ann.

Tileston School, located at 400 Ann Street, is a living memorial to the early public-education system in the city. Included on the campus are the original nineteenth-century building, the Ann Street annex of 1919, and later additions. The construction of the school was financed by Mary Tileston Hemenway, a Bostonian, who also underwrote the school’s operation for nearly twenty years after it opened as Tileston Normal School in 1872. In 1897, the school became Wilmington High School. It was later converted into a junior high and continues to serve as a public school today.

While attending this school, Woodrow Wilson was a member of its baseball team. His team roster, a diagram of the playing field, and the team cheers were later found inscribed in Wilson’s geography book.

Even though much of the original two-story, Italianate brick building is hidden behind the annexes, an examination of the splendid structure reveals windows set in ornate brick arches. Adorning the interior walls of the Classical Revival annexes are more than a half-dozen early-twentieth-century bas-relief sculptures reflecting cultural and patriotic themes.

An ancient live oak stands on the school grounds near the southeastern corner of South Fourth and Ann streets. No one is certain of the exact age of the enormous tree, but it is believed to have served as a boundary marker for the town in the first half of the eighteenth century and as a site of many important political gatherings.

At the intersection of Ann and South Fifth, turn left and walk north along the 200 block of South Fifth.

St. Mary’s Catholic Church, at 220 South Fifth, is a majestic Spanish Baroque cathedral built without steel, wooden beams and framing, or nails. Brick and tile were used throughout the structure not only for aesthetic purposes but also for structural strength. The church’s exterior is dominated by a pair of tall towers topped with domed cupolas.

When the building was completed in 1911, the St. Mary’s congregation moved from a Gothic Revival edifice at 208 Dock Street, which subsequently became the Catholic church for the black community.

In October 1868, Father James Gibbons moved to Wilmington, where he ministered to area Catholics for four years. From Wilmington, he moved to Richmond and then to Baltimore. It was in the latter city that he was notified by the Vatican on May 18, 1896, of his elevation to cardinal.

But Wilmington was the site of his most enduring contribution to his faith and mankind. On an extended visit to the city in early 1876, Gibbons began work on his celebrated Faith of Our Fathers. His inspiration came from his dynamic work with converts to Catholicism in North Carolina. Since its publication, the book has become one of the most widely read books on religion in the world. Still in print after more than a century, it has sold nearly three million copies.

Just across the street, at 219 South Fifth, stands the house where Carolina Balestier, the future wife of Rudyard Kipling, lived during a portion of her youth.

At the intersection of South Fifth and Orange, turn left on Orange and walk west 1 block to the intersection with South Fourth. Turn right and proceed north on South Fourth.

Located at 1 South Fourth, the Temple of Israel is the first Jewish synagogue erected in the state. Although the building was not completed until 1876, the Jewish community has played an important role in the life of Wilmington since David David settled here in 1738.

The Moorish-style synagogue features square towers covered with small onion domes. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the father of American Reformed Judaism, described the Wilmington house of worship in glowing terms: “For simple elegance, this temple is unsurpassed in the United States.” A state historical marker for the Temple of Israel stands on the street near the synagogue.

Located across South Fourth from the Temple of Israel, at the southwestern corner of South Fourth and Market, St. James Episcopal Cemetery is of great historic importance. Some of its ancient gravestones, more than 250 years old, are weathered to the point that they are no longer legible. Begun as a public burying ground in June 1745, the cemetery was conveyed to St. James Parish two years later. When Oakdale Cemetery opened in 1855, some of the graves at St. James were relocated to the new cemetery.

Approximately 125 marked graves remain in the St. James churchyard. They are shaded by massive oaks and cedars. Grave markers range in style from intricately carved upright stones to tabletop designs.

Among the people of note buried in this peaceful setting is playwright Thomas Godfrey. In 1758, Godfrey moved to Wilmington from Philadelphia. Several years after his arrival, he wrote The Prince of Parthia, the first play written and produced in America by an American. Godfrey died in Wilmington in 1763, four years before the play was first performed in Philadelphia. A nearby state historical marker calls attention to his grave.

Turn left off South Fourth onto Market and walk west for 1 block. Turn right on North Third and proceed 1 block north to the New Hanover County Courthouse, at the southeastern corner of North Third and Princess.

This structure is the city’s only representative of a once-popular national style: Victorian Gothic. Constructed in 1891 and 1892, the symmetrical, two-story brick structure sits upon a full basement. From the second story rises a tall bell and clock tower. The top of the tower is 110 feet above the sidewalk. From its exaggerated pyramidal roof, dormers extend outward to protect the clock faces. Still in working order, the clock and its chimes keep downtown workers and visitors apprised of the time throughout the day. Below the clock hangs the century-old, 2,000-pound bell.

Cross Princess Street to the 100 block of North Third. Located at 102 North Third, the building that houses city hall and Thalian Hall would be an invaluable asset to the largest, most sophisticated city in the United States. That such an imposing structure stands in a city the size of Wilmington is a pleasant surprise to many visitors.

In 1788, the Thalian Association, the oldest amateur theatrical group in the United States, was formed in Wilmington. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the group used an auditorium that stood on the present site of Thalian Hall. Upon acquisition of the property by the city, plans were announced for a city hall at the same location. However, the Thalians had become such an institution in the city that the citizenry rejected the construction of any building that did not include a theater.

John M. Trimble, the New York architect whose credits included the New York Opera House, was selected to design the combination municipal building and theater building. Local architect James F. Post interpreted the plans, added his creativity to them, and acted as supervising architect. Post had settled in Wilmington in 1849. His previous credits included a residence he designed for millionaire John Jacob Astor in 1840.

Completed in 1858, the original portion of the L-shaped Wilmington masterpiece fronts 100 feet on Third Street and 170 feet on Princess. As originally constructed, city hall measured 100 feet by 60 feet, while Thalian Hall stretched an additional 10 feet. The entire building is 54 feet in height. A gigantic Classical Revival portico supported by four fluted Corinthian columns dominates the Third Street facade. A second floor ballroom runs the length of city hall.

When the theater opened to a performance of The Loan of a Lover in the autumn of 1858, it boasted state-of-the-art equipment. A special apparatus raised and lowered the stage curtains. The sound of thunder could be simulated with what was called the “Thunder Run”—a trough through which cannonballs were rolled.

In 1867, the theater was leased to John T. Ford of Washington, D.C., because Ford’s Theatre in the national capital had been closed when President Lincoln was assassinated there. Years after the Washington theater reopened, experts restored it to its antebellum splendor using Thalian Hall as their basic source of information.

Throughout its long and storied history, the stage at Thalian Hall has been graced by many of America’s most famous actors, orators, and musicians. Included on the list of star performers are playwright Oscar Wilde, dressed in his English walking suit; Maurice Barrymore, father of Lionel, John, and Ethel; James O’Neill, father of Eugene O’Neill; lecturer Charles Dickens, son of the famous British novelist; Tom Thumb; William Jennings Bryan, who lectured on Prohibition; Buffalo Bill; John Philip Sousa; Lillian Russell; Marian Anderson; and Agnes Moorehead.

Unexplained occurrences have taken place in the theater for many years. Some people claim that James O’Neill haunts the place. Seances have even been held to rid the building of its ghosts. In 1966, actors noticed three figures in Victorian attire watching a rehearsal. By the time crew members reached the balcony, the figures had vanished, but three seats were turned down, as if spectators had been sitting in them.

Upon entering the restored theater building, patrons are awed by the proscenium arch, encrusted with Victorian rosettes and gilded with leaves. Ionic columns are located on both sides of the arch and outside the box seats that flank the stage. Double balconies are located above the main seating area.

As one of the very few surviving antebellum theaters in the United States, Thalian Hall is an extremely important historical and architectural treasure. After visiting the building in 1983, Tony winner Jessica Tandy remarked, “I would give anything to act on that stage.” However, it was actor Tyrone Power who best summarized the value of the historic theater. In a letter to Governor Luther Hodges dated April 10, 1958, Power wrote, “I wish I could adequately convey to you my surprise and delight upon entering Thalian Hall. It has been years since I have seen anything of its kind in this country. In fact, very few such examples exist anywhere in the world. Upon inquiry, I discovered that many of the greats of the golden age of the theatre had played there…. It has atmosphere and a history shared by all too few remaining theatres of its kind in this country.”

Continue on North Third to the intersection with Chestnut Street. Turn left and proceed 1 block west on Chestnut. Located at the corner of Chestnut and North Second, the Cape Fear Club stands as a vestige of the port city’s past. Housed in the brick Neoclassical Revival building at 124 North Second, the organization was founded in 1866 by thirteen gentlemen who wanted a common downtown meeting place. A plaque on the outside of the two-story structure bears witness to its long-established purpose: “Founded 1866, oldest gentlemen’s club in South in continuous existence. Host to many famous men.”

Turn left onto North Second and proceed 2 blocks south to the intersection with Market. Turn right, walk 1 block west on Market, and turn right on Front Street. Here, the downtown area showcases 4 blocks of century-old commercial buildings. Among the surviving architectural gems are two cast-iron storefronts.

At 2–4 North Front stands the first of Wilmington’s two skyscrapers. Completed in 1912, the Atlantic Trust and Banking Company Building was the first building in the city to rise above five stories. At nine stories, this Neoclassical Revival structure held its title as the city’s tallest building for only two years.

Walk 2 blocks north on North Front. In 1914, the eleven-story Murchison-First Union Building, at 201–203 North Front, opened its doors as Wilmington’s tallest building, an honor it retains today. Its two-story stone base is highlighted by huge Doric columns and massive windows. Crowning the skyscraper is a two-story entablature ornately decorated with a copper palmetto crown, Ionic pilasters, and other architectural features.

A few doors from the skyscraper is the site of the Bijou Theatre. When a motion-picture theater opened in a tent at 221–225 North Front in 1903, it became the first in North Carolina and one of the first in the South. Eight years later, a theater building was constructed at the site. It was demolished in 1963, but a section of the tile floor of the lobby with the name Bijou inscribed on it has been preserved in a pocket park in the busy downtown area.

Continue 2 blocks on North Front to its intersection with Walnut Street. Here, in the 300 block of North Front, the Cotton Exchange occupies the restored turn-of-the-century buildings that once housed the international cotton-exporting firm of Alexander Sprunt and Son. Today, this complex of unique shops and restaurants is connected by a maze of narrow brick walkways and wooden staircases.

Turn left onto Walnut Street and walk west 1 block to Water Street. Turn left on Water to return to your car.

Drive south on Water to its intersection with Market. Turn left on Market and proceed east 3 blocks to Third Street. Turn right on South Third and drive 7 blocks to the junction with U.S. 17/74/76/421.

En route, you will notice a large number of state historical markers lining the street. Of all the historic cities in North Carolina, Wilmington possesses the greatest number of such markers. Many of the signs on South Third honor the long list of famous people who were either born in Wilmington or called the place their home.

Among the people in Wilmington’s hall of fame are William Hooper, signer of the Declaration of Independence; Judah Benjamin, the only man to hold three different posts in the Confederate cabinet; Anna McNeill Whistler, the mother of artist James McNeill Whistler; Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of the Church of Christian Science; General Joseph Gardner Swift, the first graduate of the United States Military Academy; Johnston Blakely, naval hero of the War of 1812; Rear Admiral John Ancrum Winslow, Union naval hero during the Civil War; Admiral Edwin Alexander Anderson, winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor; Major Generals William Wing Loring and William Henry Chase Whiting, heroes of the Confederate army; Sammy Davis, Sr., entertainer and father of the legendary star of song, stage, and screen; Charlie Daniels, country-music star; Charles Kuralt, noted television journalist and author; Sugar Ray Leonard, world boxing champion; Luther “Wimpy” Lassiter, billiard champion; Althea Gibson, 1951 Wimbledon tennis champion; Meadowlark Lemon, longtime star of the Harlem Globetrotters, “the Clown Prince of Basketball”; Edwin Anderson Alderman, the only person to serve as president of three major American universities; and James F. Shober, the first known black physician with an M.D. degree in the state.

At the intersection with U.S. 17/74/76/421, South Third becomes U.S. 421 (Carolina Beach Road). Continue south on U.S. 421 across the intersection and drive 9 blocks to Lake Shore Drive. Turn left onto Lake Shore and proceed on a circular, 5-mile route through Greenfield Park.

Considered by some experts the most beautiful municipal park in the nation, Greenfield is the pride of Wilmington. Its centerpiece is a majestic, 180-acre, five-fingered lake. Hundreds of cypress trees festooned with Spanish moss dot the lake and color its placid waters coffee brown. Surrounding Greenfield Lake are more than 20 acres of colorful gardens filled with more than a million flowers, shrubs, and trees.

Prior to the American Revolution, Greenfield was a 500-acre rice plantation. For much of the nineteenth century, a gristmill operated on the lake, which was known at the time as McIlhenny’s Mill Pond. Despite its use as a millpond, the lake is not man-made. Rather, it is hundreds of years old, fed by scores of springs that bubble up from the sandy bottom.