The Wrightsville Beach to Pleasure Island Tour

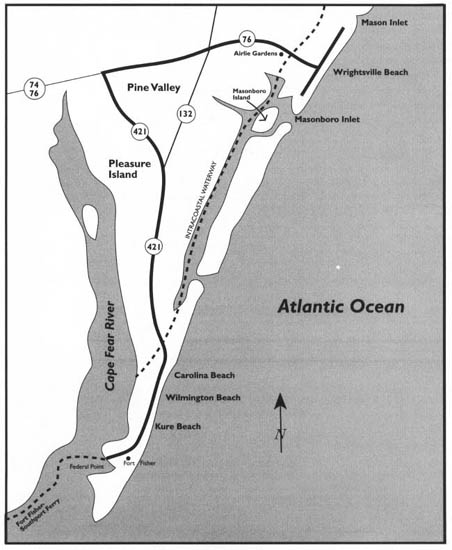

This tour begins at the intersection of U.S. 74 and U.S. 76, 9 miles east of downtown Wilmington. Proceed south on U.S. 76 for 0.7 mile and turn east on Airlie Road. The entrance sign for Airlie Gardens will come into view after 0.25 mile. Because the gardens are open for public tours for a limited time each spring, be sure to inquire in advance about the schedule.

This tour explores the islands east and south of Wilmington. From its starting point on the mainland east of town, it proceeds to Wrightsville Beach, then returns to the mainland and skirts the eastern edge of Wilmington before exploring the length of Pleasure Island, from Carolina Beach to Wilmington Beach to Kure Beach to Fort Fisher. It ends at “The Rocks,” near the southern tip of Pleasure Island.

Among the highlights of the tour are Airlie Gardens, the story of the Lumina, the story of Money Island, Carolina Beach State Park, the famous Carolina Beach Boardwalk, the story of the Ethyl-Dow Chemical facility at Kure Beach, Fort Fisher State Historic Site, the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher, and the story of the Fort Fisher hermit.

Total mileage: approximately 34 miles.

This magnificent sound-side estate of 155 acres was the country home of Mr. and Mrs. Pembroke Jones during the early years of the twentieth century. Pembroke Jones, a Wilmington native and a Confederate naval officer who served aboard the famed Merrimac, parlayed his business acumen into enormous wealth after the Civil War. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Mr. and Mrs. Jones purchased several large tracts east of Wilmington on a heavily wooded, thirty-foot bluff overlooking Wrightsville Sound.

Jones named his new country estate Airlie in honor of the home of his ancestors in Scotland. With the old Sea Side Park Hotel as a nucleus, he constructed a sprawling, multigabled, three-story mansion that contained thirty-three bedrooms and a combination ballroom and theater.

With visions of entertaining the nation’s elite, Jones commissioned his son-in-law, John Russell Pope of New York City, to design a palatial lodge nearby. Pope was at that time acquiring a reputation as one of the most able architects in America. It was Pope who collaborated with Henry Bacon of nearby Wilmington in the design of the Mall in Washington, D.C. The overall plan of the Mall and the Lincoln Memorial were products of Bacon’s genius, while the Jefferson Memorial, the National Archives Building, and the National Gallery of Art were designed by Pope.

For his father-in-law, Pope created an Italian villa so magnificent that the visiting Italian ambassador once called it “the most perfect note of Italy in America.” When completed in 1916, Pembroke Lodge was a spectacular sight. Its two-story main block and adjoining north and south wings were built of cement and covered with a tile roof. Priceless works of art, including tapestries and paintings, adorned the sumptuous interior.

Pembroke Jones lived less than three years after the lodge opened, but during that short time, he entertained the wealthiest people in the United States. Private trains brought the Vanderbilts, the Astors, and other noted families of the Gilded Age.

After the master of the lodge died in 1919, it was used infrequently by the Jones family. Gradually, thieves made their way into the compound. Looting began on a large scale in the 1930s. A fire attributed to vandals caused severe damage to the lodge in 1955.

By 1970, the terraced lawns had become a veritable jungle. Finally, the site was bulldozed for exclusive residential development, with only the three-story mansion left standing. All the while, the adjacent 155 acres of Airlie had been undergoing development as a garden showplace.

After Pembroke Jones’s death, his widow, desirous of creating one of the most beautiful flower gardens in the world, employed an internationally known gardener to achieve her goal. R. A. Toppel, a German who had for many years served as gardener to the kaiser, created what one observer called “earth’s paradise in all its glory.” In the course of his work at Airlie, he developed the Toppel tree, an unusual hybrid created by grafting yaupon to another holly.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Jones married an old friend, Henry H. Walters, a major stockholder in the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. Inside the palatial home at Airlie, Walters installed a stairway of English oak from the former home of Sir Walter Raleigh in England.

After Mrs. Walters died, her daughter sold the estate to Albert Corbett and wife, Bertha Barefoot Corbett. They demolished the rambling old mansion and in its place erected a dignified modern residence overlooking the sound.

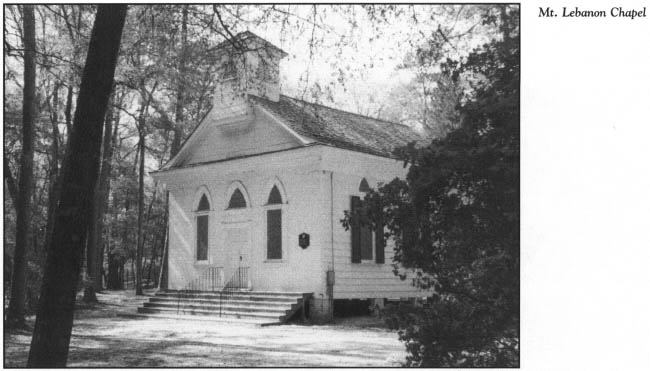

At their deaths, the Corbetts were buried in the cemetery behind old Mt. Lebanon Chapel, located on the grounds of Airlie. Erected in 1835, the small frame structure is believed to be the oldest surviving church building in New Hanover County.

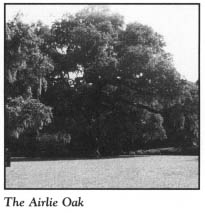

Mrs. Pembroke Jones’ dream becomes a true vision of beauty every spring, when the gardens of Airlie are opened to the public. A winding 5-mile drive enters the estate through a hand-forged gate embroidered with leaves and flowers. Along the route, ancient live oaks draped with Spanish moss shade banks of multicolored azaleas and camellias. Scientists believe one of the ancient oaks, known as the Airlie Oak, to be more than five hundred years old.

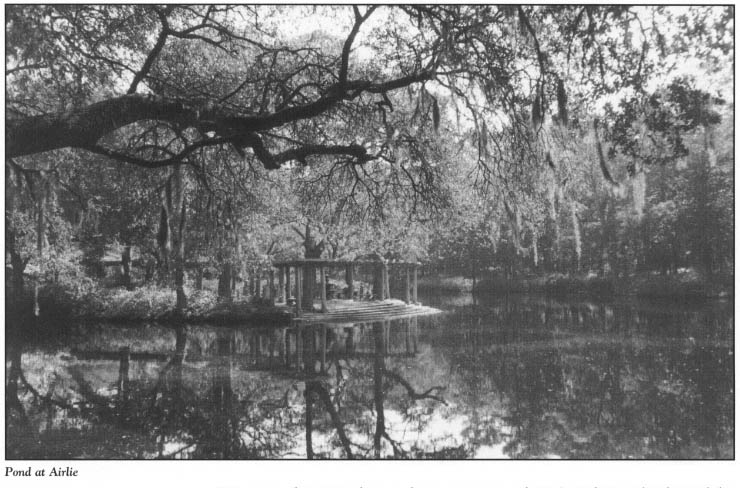

Virtually every known variety of azalea is found among the landscaped gardens. Swans swim on tranquil ponds, and lagoons mirror the colors of the seasons in their dark waters. Designed as a natural garden, Airlie has fully matured into a visual masterpiece.

Return to the entrance to Airlie Gardens and continue in your original direction on Airlie Road, which loops around to parallel the Intracoastal Waterway for 1.4 miles until it junctions with U.S. 74/76 at the foot of the drawbridge over the Waterway. This short drive provides a spectacular view of the colorful marinas, where pleasure boats of all sizes and shapes are docked and stored. Wrightsville Beach, located across the bridge from the mainland, has made a name for itself as one of North Carolina’s foremost pleasure-boating centers. Since 1853, Wrightsville has been home to the Carolina Yacht Club, one of the oldest such associations in America.

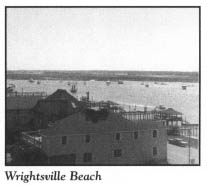

Turn right on U.S. 74/76 at the end of Airlie Road. Once you cross the drawbridge, the panorama of the granddaddy of all the resorts on the lower North Carolina coast will unfold before you. Wrightsville Beach is a 4-mile-long barrier island bounded on the north by Mason’s Inlet, on the south by Masonboro Inlet, and on the west by Banks Channel. Geographically, the barrier island is separated from the mainland by the Intracoastal Waterway, Harbor Island, and Banks Channel, from west to east. Harbor Island, a part of the incorporated town of Wrightsville Beach, is connected to the barrier island by two short bridges spanning Banks Channel.

U.S. 74/76 forks on Harbor Island. Proceed east on the U.S. 74 prong across the Banks Channel bridge to the Wrightsville Beach strand. Turn left, or north, onto North Lumina Avenue and drive 1.9 miles to the end of the paved road at the Shell Island Resort.

This northern portion of the island is known today as Shell Island. Until it was artificially filled in 1965, Moore’s Inlet, a highly unstable inlet, separated Shell Island from Wrightsville Beach. Before it was attached to Wrightsville Beach, Shell Island was for many years an uninhabited shell collectors’ paradise. Accessible only by boat, its beautiful strand was backed by imposing sand dunes.

Despite its appearance at the time Moore’s Inlet was closed, Shell Island was not without a history of human habitation. In fact, on November 15, 1910, the island hosted the flight of the first airplane ever constructed by North Carolinians. Built by two prominent businessmen from Wilmington—M. H. F. Gouverner, vice president of the Tide Water Power Company, and H. M. Chase, manager of the American Chemical and Textile Company—the airplane flew a short distance over the island landscape.

Another group of businessmen from Wilmington took an interest in Shell Island in February 1923, when an exclusive resort for blacks was begun. Before the summer season rolled around, the entrepreneurs had installed a waterworks, sewers, and electric lights. Bathhouses, restaurants, refreshment stands, a large pavilion, piers, a boardwalk, and private beach houses were quickly built. Large numbers of blacks from many states and foreign countries patronized the resort until it was abandoned after a series of fires of unknown origin destroyed many of the improvements.

Today, visitors cannot readily discern where Shell Island and Wrightsville Beach were joined. Over the past quarter-century, Shell Island has been extensively developed. By the summer of 1985, advertisements in North Carolina newspapers announced sales of the last major property to be subdivided on Wrightsville Beach, at a development called South Shell Island.

Turn around and drive south from Shell Island on Lumina Avenue. The Wrightsville Beach Holiday Inn, located 1.3 miles from the northern end of Lumina, is known to coastal geologists as “the Holiday Inlet” because it stands at the exact site of Moore’s Inlet. The pool at the hotel was featured in a 1992 episode of the television series “Matlock.” Numerous episodes of the series have been filmed in the area.

After reigning for a century as one of the premier resorts on the eastern seaboard, Wrightsville Beach remains among the best-known coastal playgrounds. On the drive down the island, you will not be able to see the ocean because of the uninterrupted hotels, motels, condominiums, cottages, restaurants, and shops that now stretch from end to end and strand to sound on the island.

Because of its long history as a heavily developed resort, the island is lacking in high dunes and maritime forests. Yet Wrightsville Beach has been able to maintain a special charm that has lured tourists here for more than a century. Located just 10 miles from Wilmington, the most populous city in North Carolina until the first decade of the twentieth century, Wrightsville Beach was the logical choice for nineteenth-century Wilmingtonians in their quest for seashore recreation.

By 1888, a steam-operated train transported passengers from Wilmington across a trestle to Harbor Island. Until that time, Harbor Island was an uninhabited island covered with gnarled live oaks. A footbridge over Banks Channel gave visitors access to Wrightsville Beach.

To meet the needs of the public, two bathhouses and a restaurant were built at Wrightsville Beach in July 1888, thus giving the resort its humble beginnings. A year later, the railroad was extended across Banks Channel. Today, South Lumina Avenue runs over the old bed of that first island railroad.

In early 1897, the island’s property owners met to formulate an agreement concerning a uniform name for the beach. Since the resort had been advertised as Ocean View for some time, the owners chose that name. Three years later, however, the resort was incorporated under its present name. The name was adopted from the nearby mainland village of Wrightsville and the sound of the same name. At the time the resort was incorporated, more than fifty houses and several rambling hotels stood on the island.

Trolley cars brought their first passengers to Wrightsville Beach on July 25, 1902. An electrified rail line carried passenger cars, each with a fifty-five-person capacity, to seven stations along the strand. Just south of the intersection of Lumina Avenue and U.S. 76 in the heart of the old Wrightsville Beach commercial district, there is a spot still called “Station One,” in honor of the first stop on the old trolley line.

As facilities were developed, Wrightsville Beach quickly emerged as the premier resort of southeastern North Carolina. In 1902, a 400-seat theater, The Casino, was completed. Fourteen years later, a huge, 2,000-seat auditorium was built on Harbor Island. Until it was demolished in 1936, this massive auditorium, which featured modern conveniences such as gas heating, served as a convention facility.

Once automobile use became widespread, the need for vehicular access to Harbor Island grew acute. A causeway to Harbor Island was constructed in June 1926. When the state purchased the Wrightsville Sound Causeway less than a decade later and announced plans to extend the highway across Banks Channel to the barrier island, the future of Wrightsville Beach as one of the state’s premier coastal resorts seemed secure. However, on January 28, 1934, a terrible fire ravaged the island, destroying more than a hundred structures, including the majestic Oceanic Hotel. Twenty years after the great fire, the island lost most of its remaining original structures to the wrath of Hurricane Hazel. Among the losses were the historic Carolina Yacht Club and the old Seashore Hotel.

North Lumina Avenue ends 0.9 mile from the Holiday Inn, at the intersection with U.S. 76 at Station One. Continue south on South Lumina Avenue, the oceanfront road on the southern part of the island. South Lumina Avenue frequently leaves and rejoins Waynick Boulevard (U.S. 76), the main road on the southern end of the island.

Located at 275 Waynick Boulevard, at old Station Three on the ocean-front, the famous Blockade Runner Resort Hotel stands at the site of the old Seashore Hotel, one of the first hotels constructed on the beach. An episode of “Matlock” has also been shot at this location.

The first public pier on the lower coast of North Carolina was a steel pier constructed at this spot as part of the Seashore Hotel complex. It is believed that the seven-hundred-foot, festively lighted metal pier, subsequently destroyed by a storm, was the only one of its kind on this entire portion of the Atlantic coast when it was erected in 1910.

Continue on Waynick Boulevard. Turn left on Nathan Avenue. A second steel pier, the Lumina Steel Pier, was constructed on the strand at 703 South Lumina in 1939. A modern fishing pier, the Crystal Pier—now the Oceanic Pier—was later built at the site.

Underneath and on the southern side of the existing pier are the remains of the Fanny and Jenny, one of the many blockade runners that were either destroyed by enemy attack or scuttled by their crews in the waters along the Cape Fear coast during the Civil War. This vessel ran aground and sank in February 1864 after being attacked by the Federal cruiser Florida.

Not just an ordinary victim of the Federal blockade of the North Carolina coast, the Fanny and Jenny carried a very special cargo that remains buried somewhere in the ship’s watery grave. A magnificent cavalry saber laden with gold and precious stones was listed on the ship’s manifest. The sword was a gift from the people of England to a man they held in high esteem. On the beautifully engraved blade was inscribed the following message: “To General Robert E. Lee from his British Sympathizers.”

Throughout the twentieth century, many divers have attempted to recover the sword, but the waters off Wrightsville Beach have not relinquished the treasure.

The pier and the shipwreck at 703 South Lumina Avenue are not the reasons that this site is considered the most nostalgic on the island. A magnificent structure once stood at this spot on the strand: the incomparable Lumina. Other than the historic lighthouses, perhaps no other structure on the North Carolina coast has achieved more fame than this nightclub, which enjoyed a fabulous sixty-eight-year run from 1905 to 1973.

In February 1905, the Consolidated Railway Light and Power Company of Wilmington decided to build the Lumina to induce visitors to ride the railway to the beach.

Elaborately constructed, the original building had a foundation of pilings driven deep into the white sand. The sills and joists of solid heart pine were of such quality that they were not moved until the building was demolished.

When the Lumina opened on June 3, 1905, it rose two stories above the Atlantic. On the first floor, a broad hallway led to bowling alleys, bathrooms, a ladies’ parlor, snack bars, slot machines, and other amusements. A broad stairway in the center of the building led to the second-floor dance hall, which measured fifty by seventy feet. Encircling the dance floor was an area from which seated spectators could watch the dancers. An orchestra balcony was located at the southern end of the dance hall and a restaurant equipped with an open fireplace at the northern end.

From the day the great pavilion opened, it aptly bore the name Lumina, a reference to the thousands of incandescent lights that illuminated the building at night. Success was instantaneous. The fame of the fabulous nightclub spread like wildfire throughout southeastern North Carolina. Capacity crowds forced several expansions of the pavilion, the first of which occurred in 1909. Four years later, bleachers were constructed on the beach, from which Lumina patrons could enjoy a spectacular view of the ocean during the day. At night, they could sit in the bleachers and view movies projected on a giant screen that rose on stilts from the Atlantic.

After it was sold to a Wilmington businessman in 1939, the Lumina no longer burned its many outside lights, and its place of dominance on the beach was lost. By the end of World War II, the grand old lady was in the twilight of her storied career, as poor maintenance, a lack of parking, and competing attractions robbed her of her vitality.

With its roof sagging and its once-glittering ballroom covered with mildew, the Lumina met the wrecking ball in May 1973. Suddenly, this palace of lights—where the likes of Tommy Dorsey, Guy Lombardo, Cab Calloway, Louis Armstrong, Kay Kyser, Woody Herman, and Lionel Hampton once performed—was no more.

The lower North Carolina coast has no truer legend than the Lumina. For years, sea captains used its brilliant lights, which could be seen for miles at sea, as a navigational aid. Long known as “the Fun Spot of the South,” the Lumina was a topic of conversation all over the world. During World War II, upon meeting a soldier from Wilmington on a remote Pacific island, a soldier from Atlanta asked, “Do they still go to the Lumina?”

From the Oceanic Pier, continue on South Lumina Avenue to the end of the island at Jack Parker Boulevard. Nearby is the dock for the Wrightsville Beach Coast Guard Station. From a vantage point on the strand on the southern end of the island, Money Island, only a few acres in size, looms on the horizon. Despite its diminutive size, this uninhabited island has generated many tales of buried treasure since the golden age of piracy.

Tradition has it that Captain William Kidd, one of colonial America’s most infamous pirates, chose the small island at the mouth of Bradley Creek to deposit two chests filled with coins and silver.

Kidd was born in Greenock, Scotland, in the middle of the seventeenth century. By the time he started plundering the North Carolina coast in the last years of the century, he was one of the world’s most dreaded pirates.

Upon completion of a particularly lucrative voyage to the Spanish colonies, Kidd returned to ravage the Carolina coast near Wilmington. After he hid some of his riches at Money Island, he sailed to New England, where he was promptly arrested. He was transported to England, where he was tried, convicted, and hanged for murder in 1701.

Whether his treasure has ever been recovered remains an unanswered question. If the chests remain where the pirate buried them, it is not because they have been forgotten. In 1858, the Wilmington Herald reported that a fisherman watched one night under the light of a full moon as several men worked on Money Island. Afraid to interrupt their activities, the man waited until the next morning to go to the deserted island. There, he found a pile of fresh earth beside a huge hole under a tree. Lines of rust were apparent on the walls of the pit, perhaps from the metal bands of one of Kidd’s treasure chests. To this day, no one knows what the men were doing or what they took that night from the sands of Money Island. Yet it was because of this incident that the island acquired its name.

In the years that followed, Money Island’s reputation as a site of hidden pirate’s treasure grew. In fact, it became pitted with holes left by treasure hunters.

Two young men from Wilmington were rummaging around the island in 1939 when they discovered a large, badly corroded iron chest with an enormous lock. Inside the chest, the youths reportedly found a rotted wooden interior but no treasure.

Nonetheless, Money Island continues to be a popular place for treasure hunters. There is probably no spot on the island that has not been subjected to a shovel. It is quite possible that any remaining treasure lies offshore in the waters of Greenville Sound, due to the migration of the island.

Just south of the tip of Wrightsville Beach lies Masonboro Island, the largest undisturbed barrier island on the lower coast of North Carolina. Squeezed between two of the most densely populated islands on the entire coast—Wrightsville Beach and Pleasure Island—the 8.4-mile-long island covers some 5,046 acres. Eighty-seven percent of the total acreage is composed of marsh and tidal flats. The remaining 619 acres make up the island’s “firm ground”—beach uplands and spoil islands.

It is one of the great ironies of coastal North Carolina history that what was perhaps the very first stretch of American shoreline to have been visited, explored, and written about by a European explorer remains uninhabited and in a pristine state more than 470 years later. Giovanni da Verrazano, a Florentine navigator in the service of King Francis I of France, caught sight of Masonboro Island in May 1524 and thereafter issued a report to the French monarch detailing what he had seen. His glowing narrative described a land of “faire fields and plains … good and wholesome aire, … sweet and odiferous flowers … [and] trees greater and better than any in Europe.”

Until 1991, Masonboro Island was the subject of a battle over preservation. The state of North Carolina, assisted by concerned citizens, has now acquired virtually all of the island so that it might be spared from development. Administered by the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management as part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve system, the island is used by the public for swimming, sunbathing, fishing, shelling, boating, and nature study.

Masonboro is not connected to the mainland by either bridge or ferry. Access is limited to private boat.

From the southern end of Wrightsville Beach, drive 1.8 miles north on Waynick Boulevard, then turn west where U.S. 76 splits off to the left. This route crosses Banks Channel onto Harbor Island and passes the former Saline Water Research Station. This facility was constructed by the federal government after World War II to serve as a world center for research into saline water conversion. The buildings in the complex are now used as municipal offices by the town of Wrightsville Beach.

As you cross the drawbridge to the mainland, you will notice a large, multistory yellow-brick building on the right. This structure once housed the famous Babies Hospital, an institution established by Dr. J. Buren Sidbury in 1920 for the medical care of babies and children. Built in 1928 to replace a building destroyed by fire, the existing Mediterranean-style structure was enlarged in 1956. The facility closed in 1978.

From the Babies Hospital, follow U.S. 76 for 4.5 miles to its intersection with N.C. 132 on the southeastern side of Wilmington. Much of this route is along Oleander Drive, the modern highway that follows the old “Shell Road”—built of crushed shells, rock, and marl—that linked Wilmington and Wrightsville Beach when the resort was in its infancy.

Turn south onto N.C. 132 (South College Road) and drive 1.2 miles to the Pine Valley Estates subdivision. Turn east on Pine Valley Drive. After 0.2 mile, turn south on Robert E. Lee Drive. As this circular road makes its way for 2 miles around Pine Valley Country Club, you may find it hard to imagine that it was here that the Confederate army made its stand to defend Wilmington—the last Southern port open to the Confederacy—in the waning days of the Civil War.

To delay the advance of Union troops making their way up the Cape Fear from Fort Fisher, Confederate forces commanded by Major General Robert F. Hoke fortified a neck of high ground between two swamps at the site now occupied by this sprawling subdivision. On February 20 and 21, 1865, the Southern troops held stubbornly and repulsed the Union forces, inflicting heavy casualties. After the Union troops regrouped and built their own defensive works, General Braxton Bragg ordered the Confederate positions abandoned, thus bringing to a close the Battle of Jumpin’ Run.

Today, other than a complex maze of streets named for Confederate heroes, there is little evidence of the final battle for Wilmington. Most of the remaining Confederate entrenchments, located in the southwestern part of the subdivision near Robert Hoke Road, fell prey to the bulldozer in 1993, when the city of Wilmington extended Seventeenth Street.

Leave the subdivision by completing the circle of Robert E. Lee Drive. Turn south on N.C. 132 and drive 3.8 miles to its intersection with U.S. 421 at a place known locally as Monkey Junction. Now a busy intersection dominated by shopping centers, the area received its name many, many years ago when a Mr. Spindle built a simple gas station and grocery store here. Behind the store, the owner kept a rather large monkey in a cage as a way to attract business. Later, he added more monkeys. Despite efforts by state highway officials to rename the intersection Myrtle Grove Junction, in deference to the nearby sound, area residents still refer to it as Monkey Junction.

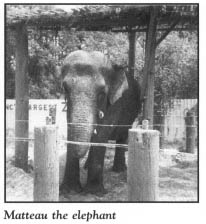

Proceed south on U.S. 421. Located 1 mile south of Monkey Junction on the eastern side of the highway, the Tote-Em-In Zoo is the largest privately owned zoo in North Carolina. More than 130 different wild animals, reptiles, and birds are exhibited. African animals include a zebra, a tiger, a lion, a camel, and numerous apes. In addition to the live animals, the facility boasts a wide variety of military artifacts and curios from the South Pacific, Africa, and South America. The zoo is the realized dream of George Tregembo, a native of Maine, who came to North Carolina in 1953.

For many years, as motorists drove past the zoo, they got a free glimpse of Tregembo’s pride and joy: Matteau. This female Asian elephant, the long-time main attraction at the zoo, could be observed in a shelter near the highway, swinging rhythmically to and fro while munching on bread doled out by zoo patrons. Matteau was by no means an ordinary elephant. When Tregembo acquired the five-ton animal in 1966, she was fifty-five years old, a rather advanced age for an elephant. When she died of a stroke on November 22, 1992, the eighty-year-old elephant was the world’s oldest living Asian elephant and one of the oldest ever recorded. She is buried near the zoo on a hill behind Tregembo’s home.

Continue south on U.S. 421. The Intracoastal Waterway separates Pleasure Island from the mainland 4.2 miles from the zoo. Before crossing the bridge over the Waterway, turn west onto River Road (S.R. 1100) and drive 0.25 mile to Snows Cut Park. Located on the northern banks of the Waterway, this twenty-four-acre recreational area, equipped with picnic facilities, restrooms, and a gazebo, is administered by New Hanover County. Park visitors are treated to a scenic view of the Waterway and the massive bridge overhead. Named for the engineer who designed it, Snows Cut is a canal linking the Cape Fear River with Greenville Sound.

Return to U.S. 421 and proceed south over the bridge to Pleasure Island.

Geographically, Pleasure Island has been called a peninsula, as has the whole of New Hanover County. Until its extensive commercial development in the twentieth century, Pleasure Island was known as the Federal Point Peninsula, named for the spit of land at its southern terminus. However, this 7.5-mile-long triangle now qualifies as an island because it is completely surrounded by water—Snows Cut on the north, the Atlantic on the east, and the Cape Fear River on the west.

Pleasure Island’s tourism industry—now its raison d’être—was born in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Prior to the Civil War, much of the island was owned by a few planters and wealthy families. All that remains of Gander Hall, one of the magnificent antebellum plantations that thrived here, is a grove of ancient oaks located thirteen hundred feet north of the intersection of Snows Cut and the Cape Fear River.

For many years, the ruins of Gander Hall had an aura of mystery. Rumors of gold hidden at the estate led a number of people to search among the ruins. Local legend has it that when a search was begun on a clear day, the sky would suddenly begin to cloud, the wind would pick up, and cries and groans would be audible over the howling wind.

Carolina Beach, the largest of the three resort communities on Pleasure Island, and one of the oldest beach towns on the lower North Carolina coast, stretches along the northern third of the island. Before visiting the bright lights, the amusements, and the general hustle and bustle of “downtown” Carolina Beach, turn west off U.S. 421 onto Dow Road approximately 0.2 mile from the bridge to Pleasure Island. It is 0.3 mile on Dow Road to the entrance to Carolina Beach State Park.

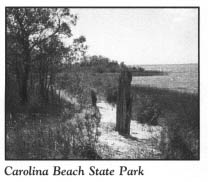

Encompassing 1,773 acres along the Cape Fear River, this park traces its roots to 1969, when the state purchased a 400-acre tract and developed Masonboro State Park. In 1974, the name was changed to Carolina Beach State Park. Created to save part of the unique natural environment along the river from development and to provide a public recreational area for visitors to the nearby resort beaches, the park continues to fulfill its original mission.

The land within the park is an evergreen shrub bog. Preserved within the park’s boundaries are a variety of important coastal ecosystems: dune ridges covered with longleaf pine and turkey oak, longleaf-pine and evergreen savannas, pocosins covered with pond pine and evergreen shrubs, swamp forests of gum and mixed hardwood, “limesink” depressions holding freshwater ponds, and brackish tidal marshes along the river. Growing in the bogs and grasslands are a number of carnivorous plants. Venus’ flytrap, parrot and trumpet pitcher plants, yellow butterwort, red sundew, and terrestrial bladderwort all thrive in the acidic, mineral-poor soil.

Five distinct hiking trails make up the 5-mile trail system in the park. Sugar Loaf Trail offers an opportunity to visit the island’s most historic natural landmark. Sugar Loaf, an ancient, sixty-foot-tall sand dune, has been used as a landmark since early European explorers charted the area. During his exploration of the Cape Fear River in 1663, William Hilton gave the dune its name. However, long before Hilton’s exploration, Indians used the Sugar Loaf area for a camp.

In 1730, the only road leading south from the Wilmington area was a sand road called “the Road to Brunswick.” It terminated near Sugar Loaf, where a ferry ran across the river to the port of Brunswick Town.

A small community grew up around the dune prior to the Civil War. In the waning months of the war, Major General Robert Hoke’s Confederate division made its camp at Sugar Loaf. From its summit, Hoke observed the battle action at Fort Fisher to the south. The entrenchments dug by his men remained in existence prior to World War II. Today, park visitors can climb to the top just as Hoke did more than 130 years ago to enjoy a panoramic view of the mighty river, the adjacent marshes, and the nearby islands.

The amenities in the park are varied. The park office is located just inside the entrance. Camping is permitted at a family campground close to Snows Cut. An amphitheater near the family campground hosts interpretive programs led by park rangers. Well-equipped picnic grounds are set amid stately oaks towering above the banks of Snows Cut. A marina, located at the end of the park road 1.3 miles from the entrance, looks out on the confluence of Snows Cut and the Cape Fear River. Parking is available at a lot midway between the amphitheater and the marina.

Retrace your route to the intersection of Dow Road and U.S. 421. Proceed south on U.S. 421 for 1.2 miles to the intersection with Harper Avenue. Turn east onto Harper Avenue, which ends after 2 blocks at the intersection with Carolina Beach Avenue in the heart of the old seaside resort. Park near this intersection and walk south to the famed Carolina Beach Boardwalk, still the focal point of local activity.

Recent restoration efforts along the boardwalk, including a $1.6-million project unveiled in 1987, have brought new life to the old taverns and nightspots, the bingo parlors, the amusements, the eateries, and the gift shops, many of which have remained in the same spot for four decades. Generations of tourists have feasted on foot-long hot dogs at The Landmark, played bingo at Red and Eve’s, and sampled donuts at Britt’s Donuts.

As they have for years, game booths line the boardwalk adjacent to the area once covered by the Seaside Amusement Park. Until it closed several years ago due to competition from Jubilee Park, a newer facility located 1 mile north on U.S. 421, the old amusement park had been a summer fixture since Hurricane Hazel. Though smaller in size, it once rivaled similar facilities at Coney Island and Atlantic City. A chairlift ride named the Skyliner, long since gone, carried passengers over a steel pier that extended well out into the Atlantic.

After visiting the boardwalk, return to your car and drive north on Carolina Beach Avenue for 1.5 miles to the end of the road.

One of the state’s oldest coastal resorts, Carolina Beach is a blend of old and new structures. Extending along the strand on the drive to the northern end of the island are countless family-style motels, apartments, condominiums, and private cottages revealing varying degrees of sophistication, and in various states of repair. Most of the structures along this route are less than forty years old, because Carolina Beach suffered cataclysmic damage when Hurricane Hazel struck her deadly blow on October 15, 1954. More than 362 cottages and other buildings were leveled, and another 375 were severely damaged.

Despite its lack of old buildings, the beach town dates back to the 1880s, when Joseph L. Winner, a Wilmington merchant, envisioned a resort on the island. Winner purchased several tracts comprising 108 acres on the northern end of the island, laid out streets and lots, and named his town St. Joseph. Because of its remote location, St. Joseph never took hold, and only scant traces of the town remain. Within the corporate limits of modern Carolina Beach, St. Joseph Avenue winds through the original tract acquired by Winner. One of the large headboats of the extensive sportfishing fleet harbored at Carolina Beach bears the name Capt. Winner.

Although Winner’s town was unsuccessful, it took less than a decade for other Wilmingtonians to recognize that his dream was a good one. By 1890, a number of residents from the nearby port city had constructed summer homes at the site of the existing resort town. Several beach hotels were completed over the next two decades.

In 1912, the Southern Realty and Development Company unveiled a five-year plan to create the finest resort on the North Carolina coast at Carolina Beach. To accomplish its goal, the company purchased almost a thousand acres on the island, including 2 miles of oceanfront. After the property was surveyed and divided into lots a year later, hordes of salesmen were dispatched around the South to sell Carolina Beach.

In 1915, an electrical plant was erected to provide the new resort town with its first electric lights. That same year saw the completion of a paved highway linking Carolina Beach to Wilmington. Five highways connecting Wilmington with other parts of the state were in place by 1922. These road projects led to the birth of the modern resort town of Carolina Beach. Motorists eager to enjoy the sand and sun began making their way to Pleasure Island from the interior of North Carolina and nearby states. In 1925, the town of Carolina Beach was incorporated.

Near the northern terminus of Carolina Beach Avenue, the effects of the severe erosion to which this portion of the island has been subjected over the past forty years are evident. There is no beach here. Instead, the shoreline consists of a thousand-foot-long sea wall of granite and rubble constructed in 1970 to control the erosion that threatens the economic vitality of the resort.

To understand the cause of the erosion that has claimed two thousand feet from the northern end of the island, park at the Carolina Beach Fishing Pier and walk onto the pier. To the north, Carolina Beach Inlet is visible. This artificial inlet was created by private interests in 1952 in response to the demands of boaters and local groups for a shorter route to the ocean from the yacht basin at Carolina Beach. At the time, boaters had to make a 12-mile trip to reach the open sea. Almost as soon as the new inlet was proposed, the Corps of Engineers warned that it would disturb the delicate balance of nature by interrupting the southerly flow of sand to the beach.

Dire warnings notwithstanding, the proponents of the new inlet prevailed. Work on the project progressed to the point that on September 2, 1952, a dynamite blast brought the tide through the new, 3,900-foot inlet.

Ten years later, a spring storm swept away an entire block at the northern end of Carolina Beach. Since the inlet was created, more than $10 million has been spent in beach renourishment and shoreline engineering projects to counteract the detrimental effects of the inlet. The battle against erosion continues.

From the pier, proceed south on Canal Drive—which runs parallel to Carolina Beach Avenue 1 block to the west—for 1.4 miles as it makes its way toward the heart of the resort. The body of water on the western side of the street is the southern portion of Myrtle Grove Sound. Located at the foot of the sound, the Carolina Beach Yacht Basin is home to one of the largest recreational fleets north of Florida.

Just north of the Carolina Beach Yacht Basin, Canal Drive intersects Harper Avenue. Turn right, or west, on Harper. After 2 blocks, turn left, or south, on Lake Park Boulevard (U.S. 421).

As you wind your way toward the middle portion of Pleasure Island, the southern section of Carolina Beach blends into Wilmington Beach, now merely an extension of its larger neighbor to the north. Over the past twenty years, numerous condominiums and high-rise towers have been constructed along this mile-long stretch of strand.

The history of Wilmington Beach is another story of shattered coastal dreams. In 1913, the Wilmington Beach Corporation brought forth grandiose plans for a magnificent resort that was to include a pavilion, several ocean piers, tennis courts, a waterworks, and an electrical plant.

The centerpiece of the new vacation spot was to be a large hotel. When The Breakers finally opened to the public in May 1924, the modern, fifty-room building towered three stories above the Atlantic. Unfortunately, this sturdy structure, the first brick hotel erected on the New Hanover County seashore, was no match for the fury of Hurricane Hazel. So severe was the damage to The Breakers that it was demolished several years later. No evidence of the great hotel remains at Wilmington Beach, but bricks and rubble from its ruins were used to line the seaward face of Fort Fisher in the ceaseless battle against erosion there.

Even with the construction of The Breakers, Wilmington Beach never reached the stature envisioned by its developers. Many individual lots were sold, but when the Dow Chemical Company purchased a tract of 310 acres for the construction of a plant near the hotel, the future of Wilmington Beach as a resort was doomed.

Continue south on U.S. 421. Until it was developed with beach cottages in the early 1990s, the 1.5-mile stretch of strand between Wilmington Beach and Kure (pronounced Cure-ee) Beach was a popular public beach that attracted hordes of sun worshipers during the summer season.

Nearby is the site of a federal-government project that draws stares from passing motorists. Located on both sides of the highway are chain-link enclosures containing various metal contraptions that resemble solar panels. For decades on this site, various metals have been exposed to the marine environment to test their susceptibility to corrosion. In recent years, a national magazine advertisement has spotlighted this federal project.

Other than a marker erected by the state south of the metal-testing area, modern Kure Beach gives no hint of the vital, unique, and successful scientific experiment that took place here more than a half-century ago. In 1931, the Dow Chemical Company and the Ethyl Corporation pooled their resources to begin construction of the world’s first installation for the extraction of bromine from seawater.

Several important developments in the 1920s led to the need for the facility. During that decade, not only were more automobiles being built and sold in the United States, but the new vehicles were bigger and better than those of previous years. Ordinary gasoline was no longer satisfactory for the high-performance needs of the newer engines. The discovery of tetraethyl lead fostered the development of “high test” gasoline, or ethyl, as it was known in the trade. When added to gasoline, tetraethyl lead increased the antiknock capacity of an engine, thus improving its performance. When the new gasoline product was introduced in 1923, it was enthusiastically accepted by the motoring public, but the concern of health officials over its lead content resulted in a federal ban of the sale of ethyl gasoline for two years.

Meanwhile, intensive research showed that the addition of ethylene dibromide, of which bromine is a major component, made the fuel safe. When ethyl was once again made available for public use in 1926, sales skyrocketed. The industry was thus forced to search for a source of bromine, because supplies of the mineral were rapidly being depleted. Laboratory tests convinced officials from Dow Chemical and the Ethyl Corporation that the critical need for bromine could be satisfied by its extraction from seawater.

Experiments conducted on a floating laboratory in the continental waters of the United States convinced officials from both companies that bromine could be extracted from water close to shore with minimal difficulty. After considering a number of sites for the location of a revolutionary plant, the newly formed Ethyl-Dow Chemical Corporation selected Kure Beach as the ideal spot.

In 1933, some fifteen hundred workmen were employed in the construction of the massive facility. Seawater first entered the intake valves in January 1934. For eleven years thereafter, much of the nation’s bromine was supplied by the facility on the northern side of Kure Beach. The plant, a complex network of pipes and towers, captured scientific attention as the first of its kind in the world. By conclusively proving that the riches of the oceans could be mined in a practical way, the installation came to be considered one of the scientific marvels of the twentieth century.

Expansions at the plant allowed scientists to discover a wealth of by-products in the bromine extraction process. Among the riches contained in the massive quantities of water processed at the plant were enough gold to make a five-inch ball; enough silver to make a twenty-five-inch ball; enough epsom salts to supply every American with nine pounds each; enough potassium chloride to fertilize a million acres of farmland; enough copper to fabricate 1,120 miles of twenty-gauge wire; enough aluminum to make sixty-eight thousand automobile pistons; and enough common salt to put down pavement one foot thick and twenty-six feet wide from New York City to Washington, D.C.

Security was given the highest priority during World War II, because of the facility’s vulnerable coastal location and the vital product it produced. Patrol squadrons flying out of Elizabeth City provided twenty-four-hour surveillance. Nonetheless, the plant was the target of a U-boat attack in the wee hours of a Saturday morning in 1943. An army pilot spotted a German submarine 5 miles offshore just as it was firing its deck gun at the plant. Five shots were fired, all of them errant, either landing in the Cape Fear River or beyond in Brunswick County.

Once the submarine was sighted, the pilot dispatched a radio report which resulted in an air-raid alert in the Wilmington area. As sirens pierced the night, the entire area was blacked out while American warplanes searched in vain for the U-boat.

Shortly after the war, the decision was made to phase out operations at the Kure Beach facility, due to the construction of a large, modern plant in Texas. By January 1946, the plant that pioneered the production of bromine from seawater was closed forever. Finally, on February 1, 1956, a demolition crew from Florida began a complex, nine-month job of dismantling the facility. Once that task was completed, the site of one of the great experiments in the history of science was given back to nature.

On the 1.6-mile drive south from Wilmington Beach to Kure Beach, you will notice a marked change in the age and sophistication of structures on the strand highway. Kure Beach is dominated by family vacation cottages and mom-and-pop motels, restaurants, and businesses, much as it has been since its birth in the last decade of the nineteenth century.

Though not as large and well known as Carolina Beach, Kure Beach is almost as old. In 1891, Hans Kure, a native of Barnholm, Denmark, was fishing with a group of Wilmington businessmen near the wreck of the blockade runner Beauregard when he conceived the idea of a commercial enterprise at the place which today bears his name.

As a young sea captain, Kure had become familiar with the North Carolina coast when his ship wrecked near Beaufort in the early 1870s. After recuperating in a Beaufort hospital, he returned to his native land, but he could not forget the excellent care and genuine friendship extended to him by the people of the North Carolina coast. By 1879, he settled in Wilmington, where he operated a ship chandlery and a stevedoring business.

Immediately following his 1891 fishing trip to Pleasure Island, Kure acquired oceanfront property 2 miles south of Carolina Beach in an area of rolling sand dunes, beach grass, and scrub oaks. By early summer, his beach holdings included a bowling alley and a saloon.

More than a century later, Kure’s resort remains a small, unpretentious vacation town. Missing from Kure Beach are the bright lights and amusements that have made Carolina Beach one of the state’s most popular resorts.

To sample the easygoing atmosphere of Kure Beach, park near the traffic light on U.S. 421 in the heart of town and walk to the Kure Beach Fishing Pier, the resort’s claim to fame.

Not only is the 950-foot pier the oldest on the coast of the Carolinas, but it is also believed to be the oldest on the entire Atlantic coast. Constructed of untreated wood by L. C. Kure in 1923, the original pier was 120 feet long and 12 feet wide. After only a year, it succumbed to the elements, but Kure rebuilt. In the process, he substantially enlarged the pier and strengthened it with concrete posts reinforced with railroad iron.

Since that time, the pier has been rebuilt eleven times. When Hurricane Hazel struck Kure Beach, the concrete pilings were not broken by the savage wind and waves. Instead, they were knocked over. They now lie on the ocean floor near the pier.

After visiting the pier, continue south on U.S. 421. Much of the land on Pleasure Island south of Kure Beach is owned by the state and federal governments. Consequently, the southern end of the island has been spared widespread commercial development. The only exception is a strip of oceanfront property just north of the old Fort Fisher Air Force Base. Here, the resort village of Fort Fisher has fallen prey to condominium construction.

To the south of the former base, the northern limits of which are marked by two imposing concrete pillars on the shoulder of U.S. 421, the government holdings are put to various uses: a recreational retreat for military personnel from North Carolina bases; Fort Fisher State Historic Site; Fort Fisher State Recreation Area; the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher; the Fort Fisher-Southport Ferry; and “the Rocks.”

One of coastal North Carolina’s newest museums opened on the grounds of the former air-force base in August 1991. Housed in a National Guard building on the western side of U.S. 421 approximately 1 mile south of Kure Beach, the North Carolina Military History Museum offers exhibits of uniforms, firearms, and other military memorabilia. It was founded by the North Carolina Military Historical Society.

Continue to Fort Fisher State Historic Site. The combination visitor center and museum is located on the western side of U.S. 421 south of the old air-force base.

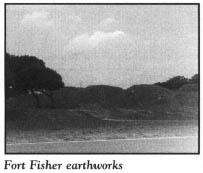

In spite of a constant struggle for funding since it was established in 1961, Fort Fisher State Historic Site remains the most-visited state historic site in North Carolina. And although the visitor center-museum was never completed as designed—the architect envisioned a structure that would give visitors the feeling of entering a bunker—it remains one of the focal points of the mighty Civil War fortification. The visitor center-museum offers information about the history of the fort, the famous battles fought here, and the preservation of the remaining earthworks. Without this information, unwary visitors who expect to see a stone or cement fortification might pass right by the remains of the fort without noticing them.

Inside the museum, a short audiovisual presentation documents the vital role that Fort Fisher played in protecting the Cape Fear area and local blockade runners, which successfully ran the Federal blockade 1,835 times out of 2,054 attempts. Interpretive exhibits display letters, maps, and charts concerning the fort, as well as artifacts recovered from the area. Shells and cannonballs are grim reminders of the massive sea-to-shore bombardment that took place here.

To the rear of the building is all that remains of the once-massive fortification, a complete model of which was used for study in classrooms at West Point after the Civil War. Even though a road and an airstrip were constructed through the fort during this century, a significant portion of its land face remains. To preserve the half-dozen or so mounds that still exist, the state has seeded them with grass. A palisade similar to the one that protected the land face has been constructed.

A trail winds around to the other side of the mounds and leads to the end of the earthworks near the Cape Fear River. It is here that visitors can best visualize how the interior walls of the fort looked, thanks to the work of state archaeologists and site officials.

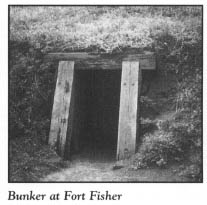

In the late 1970s, archaeologists unearthed the “bombproof’ nearest the river. From the information gained in that project, a bombproof has been reconstructed, the entrance to which is on the side of the mounds opposite the museum.

Just north of the museum and adjacent to the parking lot is the Underwater Archaeology Laboratory, operated by the North Carolina Division of Archives and History. The laboratory, with its five-person staff, is an outgrowth of the centennial celebration of the Civil War and the attendant activities at Fort Fisher. Its curator promptly took steps to salvage some of the forty blockade runners that had been lost just offshore.

Since the facility’s opening, divers from the lab have located and explored more than three hundred shipwrecks in North Carolina waters. In addition to preserving Civil War artifacts, the lab has preserved twenty-six dugout canoes used by the prehistoric Indians of Lake Phelps.

The cannon that greets visitors at the museum entrance was discovered by the Fort Fisher laboratory. It came from the USS Peterhoff, which went down in nearby waters in 1864 after colliding with another United States Navy vessel.

Several years ago, the laboratory was honored as one of the top five of its kind in the nation. Today, it may very well be the best. Throughout the past quarter-century, its staffers have pioneered many of the processes now in widespread use to protect iron after long periods of exposure to seawater.

Directly across U.S. 421 from the visitor center-museum and the parking lot is a picnic area, located in a majestic oceanfront setting under a canopy of live oaks gnarled by the wind blowing off the sea.

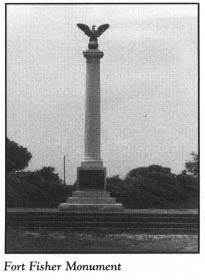

Just south of the picnic area, and within walking distance, stands the Fort Fisher Monument. Since 1932, this tall stone shaft has towered above the ever-encroaching Atlantic. Surmounted by a large eagle atop a sphere, the monument is located at a spot known as Battle Acre. At its unveiling, the Confederate flag flew over Fort Fisher for the first time since its surrender.

Proudly displayed at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, is the magnificent, 150-pound, mahogany, carriage-mounted Armstrong gun presented to the officers and men of Fort Fisher by Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president.

In the not-too-distant future, that gun and other relics like it may be all that remain of the old fort. Nothing man has tried over the past six decades has halted the onslaught of erosion. More than three-quarters of the original fort has been eaten away by the sea. Nonetheless, from the parking lot at Battle Acre, visitors can gaze up and down the beach and imagine how the sprawling fortress must have looked.

Named for Colonel Charles Fisher, a North Carolina hero who died at First Manassas, the fort was constructed and enlarged throughout the four years of the Civil War. Major General William H. C. Whiting, the adopted North Carolinian who had the highest grades at West Point prior to the matriculation of Douglas MacArthur, and Colonel William Lamb, a young newspaper editor and attorney from Virginia, were the geniuses behind this coastal citadel, which quickly earned the nickname “Gibraltar of America.” Embracing a sea face of more than a mile (1,898 yards) and a land face of more than a third of a mile (683 yards), the L-shaped fort was enormous. Stretching down the long sea face were seventeen heavy gun emplacements.

The earthwork walls rose twenty feet above the sea. They were constructed with a forty-five-degree slope to make it difficult for an assaulting land force to gain entry. As a cushion against heavy gunfire from enemy ships, the walls of the parapet were twenty-five feet thick.

At the southern end of the sea face stood the imposing Lamb’s Mound Battery. Towering sixty feet, this gun emplacement was armed with long-range guns for the defense of New Inlet, the primary river entrance used by blockade runners en route to Wilmington. Farther to the south, at the tip of the island, was a tall, oblong fortification called Battery Buchanan, an auxiliary part of the fort.

Many of the thousands of treatises written on the Civil War have failed to relate the extreme importance of the Union capture of Fort Fisher to the ultimate demise of the Confederacy. Six months before the war ended, General Robert E. Lee warned, “If Fort Fisher falls, I will have to evacuate Richmond.” Indeed, half the supplies for Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia were flowing through the port of Wilmington at that time.

In retrospect, Alexander H. Stephens, vice president of the Confederate States of America, commented, “The fall of this Fort was one of the greatest disasters which had befallen our cause from the beginning of the war—not excepting the loss of Vicksburg or Atlanta.”

Fort Fisher fell to combined Union forces on January 15, 1865. General Lee surrendered at Appomattox less than three months later.

The Confederate garrison of fewer than two thousand men did not surrender the Cape Fear installation until it exhausted its entire supply of ammunition. Those men waged a three-day battle against the largest war fleet ever assembled to that time and an invading land force of some ten thousand Union soldiers, sailors, and marines. During the struggle, the guns of the fleet hurled more than fifty thousand shells at the fort. After Fort Fisher capitulated, the federal government excavated a thousand tons of iron from the battle site. Yet after three days of the heaviest sea-to-land bombardment the world had ever witnessed—and since surpassed only by the assault on Normandy eighty years later—not one of the forts bombproofs or magazines was damaged.

Just south of the Fort Fisher Monument, the state has established the Fort Fisher State Recreation Area, a 237-acre tract along the undeveloped strand. First-time visitors to the shore in this area are surprised, and often alarmed, to see huge chunks of concrete and riprap which have been deposited at the edge of the embankment running along the shore in the vicinity of the old fort. This rubble fortification has been put in place to stem the tide in the constant battle against erosion.

Rocks are abundant in this area, both in the tidal zone and submerged in the shallow waters. However, these rocks are not remnants of an earlier fight with erosion. They are coquina outcrops—the only natural rock exposures on the entire North Carolina coast.

Coquina is a combination of shells and estuarine fossil fragments cemented together in a natural process by calcite. Most of the rock formations are now submerged at high tide. At low tide, much of the rocky area is exposed, disclosing potholes and cracks filled with various sea creatures and algae.

Continue south to the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher, located on the ocean side of the highway 0.2 mile from Fort Fisher State Recreation Area.

The North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher is the southernmost of the state’s three public marine centers. Housed in a modern multilevel building, the center features aquariums, exhibits, conference rooms, research laboratories, and offices. On the lower level, the 20,000-gallon shark tank, the largest aquarium in the state, is the most popular exhibit at the facility. Films and programs dealing with many aspects of coastal life are offered by the aquarium. Off-site excursions are offered as well.

The several hiking trails developed on the twenty-five-acre oceanfront complex afford visitors an opportunity to enjoy the coastal habitat in its natural state. One of the nature trails leads to the former home of one of the most colorful residents of the area. Throughout the year, the aquarium offers guided hikes to the structure where the Fort Fisher hermit once lived. From 1955 until his death in 1972, Robert Edward Harrell called Fort Fisher home.

When he arrived at Fort Fisher at the age of sixty-two, Harrell lived in a tent near the Fort Fisher Monument. As to why he left his hometown of Shelby, the native North Carolinian would only say that he came to write his book. That he did. However, A Tyrant in Every Home was never published. In Shelby, Harrell had earned a living as a newspaper typesetter and itinerant jewelry salesman. His wife and children had left him in the 1930s.

Regardless of what led him to the Cape Fear area, Harrell never wanted to leave after he arrived. He quickly exchanged his tent home for an abandoned World War II bunker in the desolate salt marshes in the vicinity of the present aquarium. Both the federal and state governments were displeased with Harrell’s use of the bunker as a dwelling, but the man used his wit, charm, and personality to dissuade all agencies from evicting him.

Harrell lived alone except for a pack of mangy dogs which kept him company. He kept his few worldly possessions hidden in piles of debris around the bunker. His diet consisted primarily of berries, shrimp, oysters, fish, and other seafood caught at nearby Buzzard’s Creek. To supplement his diet, he cultivated a small garden. He drank rainwater coffee. Island residents brought food to him on occasion, and he made trips to Carolina Beach to shop at the nearest supermarket.

Except in extremely cold weather, the hermit’s dress was nothing more than an old bathing suit and a floppy straw hat. Only on the coldest days did he don an overcoat and shoes. His hair and beard were untrimmed, and he bore a striking resemblance to Ernest Hemingway. Years of exposure to the sun toughened his skin to the point that he did not even feel the bite of coastal deer flies, which bring pain to most people. As he grew older, his hunched back made him look shorter than his five-foot-three-inch height.

As his presence became known, hordes of visitors descended upon his domain. Harrell claimed that as many as seventeen thousand people visited him in a year. His visitors almost always left highly impressed with the hermit’s intelligence. He often engaged those invading his solitude in conversation about politics, religion, and the coast. Visitors were required to sign a register maintained by Harrell, who did not object to being photographed.

The hermit was not only well read, but shrewd as well. When visitors called, they were greeted by an old frying pan outside the bunker. In the pan, Harrell put “seed money”—a half-dollar, a quarter, a dime, a nickel, and a penny. By doing so, he said he was using psychology on people. When they saw the penny, they knew that a penny was welcome, and likewise a nickel, a dime, a quarter, or a half-dollar. In return for a donation, the hermit always gave his visitors something, whether it be a piece of shrapnel or a seashell.

On June 4, 1972, some boys ventured to the bunker to call on the hermit. They found his dead body, his raincoat bunched around his neck. His legs were bloody. Shoe prints in the sand seemed to indicate that his body had been dragged.

A coroner’s report concluded that Harrell died of natural causes. His body was taken back to Shelby for burial. Harrell’s son, Ed, was not convinced that his father’s death was natural. At his request, the body was exhumed in 1984 for an autopsy. Once again, no evidence of foul play was found.

To those who knew him on the island, Harrell had expressed his desire to remain at Fort Fisher. He told people not to worry about burying him—he advised them to leave his body for the crabs to eat.

On the seventeenth anniversary of his death, friends and relatives reburied the hermit in a grave on the island he had affectionately called home. The grave is covered with shells and a tombstone, which prophetically reads,

Robert E. Harrell

The Fort Fisher Hermit

“He Made People Think”

February 2, 1893

June 4, 1972

Continue south on U.S. 421. It is 1.3 miles from the aquarium to the Fort Fisher-Southport Ferry landing, located near the tip of the island, known as Federal Point. From this point, a state-operated ferry carries passengers and vehicles across the Cape Fear River to Southport, thereby avoiding a 50-mile trip by road.

Two historic sites are located adjacent to the ferry landing. Within walking distance is the last point of rendezvous for Confederate forces during the final assault on Fort Fisher: Battery Buchanan. A small sign erected by the state directs visitors to this rather tall, grassy mound, where the sun set on the Confederacy. A parking lot and a public boat-access area are located at the site.

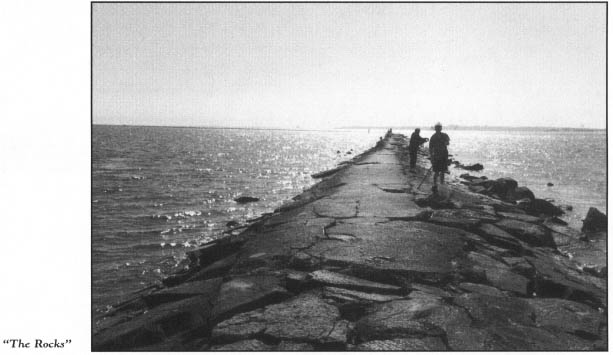

Located on the riverfront just south of Battery Buchanan, “The Rocks” is a popular recreational spot. Hordes of people fish, swim, picnic, and sightsee on or near the dam that saved the port of Wilmington. Yet few visitors who walk atop this architectural masterpiece realize the magnitude of the dam below them.

“The Rocks” closed New Inlet, which had been opened by a raging storm in 1761. The inlet was used by countless ships during the Civil War. Anna McNeill Whistler, better known as “Whistler’s Mother,” made her way through New Inlet during the conflict to join her famous artist son in Europe.

In order to maintain a navigable river channel to the port of Wilmington, the Corps of Engineers recommended in 1874 that New Inlet be closed with a dam. Captain Henry Bacon, an engineer from Wilmington, was the mastermind of the project.

To construct the dam, large rafts of logs and brush weighted with massive quantities of stone were sunk for almost a mile from Federal Point to Zekes Island. When the base of the dam was completed, it was 90 to 120 feet wide. Sufficient quantities of rock were barged in and dumped onto the base to raise the dam to the water level—a height of 20 to 25 feet. Since the dam’s completion, engineers have determined that the rock used in the project would build a stone wall 8 feet high, 4 feet thick, and 100 miles long.

Few engineering feats in American history have surpassed “The Rocks.” Recognized internationally as an engineering landmark, the project has been designated one of the twelve “Best Ever” projects completed during the two-hundred-year history of the Corps of Engineers.

The tour ends here, near the southern tip of Pleasure Island.