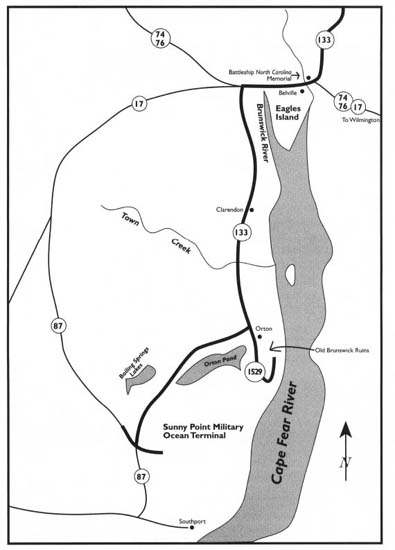

This tour begins on U.S. 421 just north of the intersection with U.S. 17/74/76 on the western side of the Cape Fear River, 2 miles from downtown Wilmington. Follow the giant red and blue sign for the Battleship North Carolina, which directs you down S.R. 1352 to Eagles Island.

This tour begins at Eagles Island, home of the Battleship North Carolina Memorial, then follows the course of the Cape Fear River to Belville, Orton Plantation, and Brunswick Town State Historic Site before ending near Boiling Spring Lakes.

Among the highlights of the tour are the legendary Battleship North Carolina, the story of “the Ghost Fleet of Wilmington,” the story of the Cape Fear plantations—chief among them Clarendon, Old Town, Pleasant Oaks, and Orton—and the story of Brunswick Town and Fort Anderson.

Total mileage: approximately 37 miles

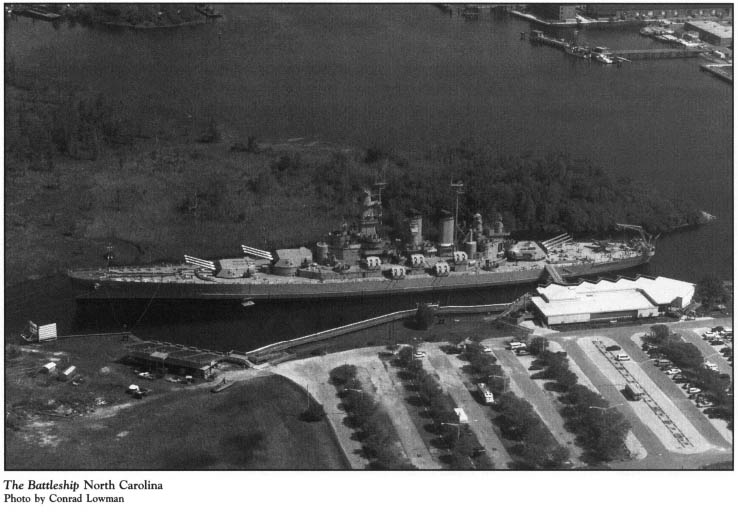

Eagles Island is the home of one of the most captivating sights in all of coastal North Carolina. Three decades have now passed since a Southport river pilot, Captain B. M. Burris, skillfully guided the USS North Carolina (BB-55) into the Cape Fear River en route to its permanent berth here, on the New Hanover County-Brunswick County line.

Named for Richard Eagles of Bristol, England, an early planter in the region, the island was linked to Wilmington in pre-Revolutionary War times by a causeway built of large ballast stones and sacks of soil thrown overboard from ships from all over the world. Almost 250 years later, flowers and plants foreign to North Carolina, including the bonny bluebells and thistle of Scotland, thrive on the marshy, semitropical island. Known as “the Granary of the Commonwealth,” the island produced abundant quantities of rice in the eighteenth century. Eagles Island helped make Carolina rice world-famous.

At the end of the short, scenic drive looms the enormous warship, moored in the shadow of the Wilmington waterfront. A green picnic area and a spacious parking lot shaded by live oaks laden with Spanish moss greet the 250,000 visitors who annually walk the teakwood decks, climb onto the once-potent guns, and examine the bowels of one of the most battle-tested, highly decorated ships in the history of the United States Navy.

Still emblazoned on the hull of the North Carolina is the number 55, signifying that the ship was the fifty-fifth battleship laid down for the navy. Of the fifty-four that preceded her, two bore the proud name USS North Carolina.

The first North Carolina, launched in 1820 and commanded by Master Commandant Matthew C. Perry, quickly became the envy of the navies of the world. Much like her namesake now berthed at Eagles Island, the original North Carolina was the “show ship” of her day. She was invited to call at ports all around the world, where dignitaries and heads of state marveled at her beauty and power.

The keel for the second North Carolina (BB-52) was laid in 1919. Had this ship been completed, it would have been the largest, mightiest, and most modern battleship in the world. But the post-World War I “Five Power” treaty called for a ten-year period during which no new warships could be completed. Thus, the hull of the second North Carolina was sold for scrap in Norfolk in 1923.

On June 9, 1940, four days before the hull of the current North Carolina slid down the ways at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, German troops entered Paris.

When the United States Navy commissioned this, the mightiest naval vessel in the world, at an elaborate ceremony ten months later, on April 9, 1941, correspondents from all over the world were on hand to witness the unveiling of the first modern battleship. The $77-million ship was the first to incorporate new shipbuilding technology with heavy armament, strong protection, and speed.

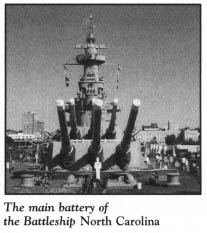

Stretching more than 728 feet, the 45,000-ton battleship was more than 200 feet longer than World War I battleships. When she was launched, no ship in the world could match the North Carolina in firepower. The main battery of nine 16-inch guns could accurately fire armor-piercing, 2,700-pound projectiles up to 22 miles.

As the forerunner of the mighty battleships to follow, it was the North Carolina that wrestled with new equipment, ironed out wrinkles, and generally set the standard for future ships in the American fleet. Chosen to be a class leader, the awesome battleship wore its crown well.

In the course of her six-month shakedown cruise, the dreadnought made her way back to the Brooklyn Navy Yard many times for technical conferences and adjustments. New Yorkers, including radio-newspaper personality Walter Winchell, grew so accustomed to seeing the graceful ship entering and leaving New York Harbor that they nicknamed her the “Showboat,” after the riverboat in the Edna Ferber novel and the subsequent musical of stage and screen.

The North Carolina and her sailors were in port at New York City when the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Less than six months later, the ship was ready to take her place as one of the greatest fighting vessels in world history.

On May 29, 1942, the North Carolina put in at Hampton Roads, Virginia, to take on ammunition. From there, she sailed for the Panama Canal Zone on June 4. Six days later, the Showboat earned the distinction of being the first battleship to pass through the Panama Canal during World War II. On June 24, the ship arrived in San Francisco, where she spent ten days while final plans were formulated for her entry into the war for the control of the Pacific. Departing from San Francisco under the guise of a training cruise on July 5, the battleship received orders at sea a day later to proceed to Pearl Harbor.

After the virtual destruction of the American fleet in the Pacific, the aged, battered remnants of the United States Navy struggled valiantly for survival against an overwhelming opponent, the Imperial Navy of Japan. The news from the Pacific in the early days of the summer of 1942 painted a bleak picture. Against this backdrop, the United States prepared to unleash the mightiest ship the world had ever known.

On the afternoon of July 11, 1942, the sailors of the beleaguered fleet at Pearl Harbor witnessed a sight they would never forget. Looming on the horizon, under the escort of a carrier and several cruisers, appeared the largest, mightiest, and most modern ship on the seas. Tumultuous cheers rang out all along the harbor as the Showboat made her way past the twisted wreckage of the USS Arizona.

Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, the commander of the United States Navy in the Pacific, reflected upon the arrival of the North Carolina: “I well remember the great thrill when she arrived in Pearl Harbor during the early stages of the war—at a time when our strength and fortunes were at a low ebb. She was the first of the great new battleships to join the Pacific Fleet, and her presence in a task force was enough to keep our morale at a peak. Before the war’s end, she had built for herself a magnificent record of accomplishment.”

Soon after her arrival at Pearl Harbor, she went on the offensive, becoming the first American battleship to fire into Japanese territory. During the three and a half years that followed, the North Carolina spent more than forty months in combat zones. In the long history of the United States Navy, only a handful of ships have served longer stints in the face of the enemy.

Her most significant contribution to the war effort was the protection she provided for aircraft carriers. With cover from the North Carolina, thousands upon thousands of bombing missions were successfully flown by carrier-based airplanes against enemy targets.

Her long Pacific tour covered some 307,000 miles. Along the way, the mighty warship was the only American battleship to take part in all twelve major naval offensives in the Pacific theater. Her unsurpassed fighting ability and the bravery and savvy of her crew earned the battleship twelve battle stars, covering operations from Guadalcanal to the Japanese islands.

Ironically, the war that the North Carolina helped win produced the technology that spelled doom for virtually all battleships. At the Battle of Leyte Gulf and other struggles in the Pacific, the fallibility of big battle wagons was apparent. Aircraft from modern carriers could swiftly strike devastating blows against the relatively slow ships.

With her obsolescence as a weapon of war assured, the life expectancy of the North Carolina diminished rather quickly after World War II. On June 27, 1947, the proud warship was decommissioned. For the next fourteen years, she swung at anchor in relative obscurity as one of the many fighting vessels in the “Mothball Fleet” at Bayonne, New Jersey.

Concern grew in North Carolina over the future of the battleship when on June 1, 1960, naval officials confirmed rumors that the vessel would be scrapped. Exactly five months later, the ship was stricken from the official United States Navy list.

Working against time, state officials, public-minded citizens, and schoolchildren all over North Carolina rallied to raise money to save the ship from the blowtorch. By September 12, 1961, people from all walks of life had contributed nearly $236,000 to acquire the ship, to prepare the site at Eagles Island, and to transport the ship to the berth. More than seven hundred thousand schoolchildren brought nickels and dimes to school in a herculean effort that raised a third of the necessary funds.

On October 14, 1961, the dream of many North Carolinians came true when the Showboat welcomed visitors to its decks for the first time as a battleship memorial.

In March 1986, the memorial was designated a National Historic Landmark. Later that year, the name was changed from the USS North Carolina Battleship Memorial to the Battleship North Carolina Memorial amid speculation that there might one day be another USS North Carolina in the active service of the United States Navy.

Since the ship was first opened to the public, additional portions of its interior have been made accessible to visitors. Among the areas now open are the teakwood decks, the engine rooms, the cobbler shop, the ship’s store, the laundry, the print shop, the crew’s mess and quarters, the officers’ quarters, the sick bay, the combat information center, and the pilothouse. Several of the turret chambers of the 16-inch guns are open. Audio stations provide messages of interest along the self-guided tour.

Prominently displayed on deck near the stern is a restored OS2U Vought Kingfisher airplane. Three of the aircraft were carried by the ship during the war. These low-wing monoplanes were launched from two sixty-eight-foot catapults on the stern. The planes were used for observation of long-range gunfire, antisubmarine patrol, message drop, sea rescue, aerial photography, and shore liaison. Upon returning from a mission, they landed in the water near the battleship and were hoisted from the water by a deck crane.

Only fifteen hundred of the special aircraft were built during World War II, and very few remain in existence. In 1968, the wreckage of the craft featured aboard the battleship was discovered by the Royal Canadian Air Force in the rugged mountain wilderness of Alaska, where it had crashed in 1942. After the plane was salvaged, it was shipped to Dallas, Texas, where retired workers of the Vought Aeronautical Company volunteered to restore it. After the painstaking task was completed, the wings and fuselage were trucked to Wilmington for assembly.

Inside the Battleship Memorial Museum, located aboard the ship, are many photographs and artifacts related to the history of the North Carolina. One of the prominent exhibits is the “Roll of Honor”—a list of every North Carolinian who died during World War II in the service of the United States.

In the late 1980s, a new visitor facility—which includes an orientation center, a ticket office, a gift shop, a snack bar, and restrooms—was completed adjacent to the ship.

No summertime tour of the battleship is complete without an appearance by the resident alligator, Charlie, who often swims in the waters alongside the vessel.

Not one cent of government money—state or federal—has ever gone toward the operation of the battleship memorial. Managed by a sixteen-member commission appointed by the governor, the ship is maintained with funds generated from admissions, gift-shop and snack-bar revenues, and gifts.

The great battleship at Eagles Island is one of the premier attractions on the North Carolina coast and a significant landmark of American history. Except for the New Jersey, which served the nation for a much longer period of time, the North Carolina is the most-decorated vessel in the history of the United States Navy.

From the grassy picnic area at the battleship, visitors can enjoy the spectacular beauty of one of America’s greatest rivers. Of all the historic rivers in eastern North Carolina, none has been more important in the settlement, development, and economic growth of the coastal plain than the mighty Cape Fear.

The only river in the state that offers a direct deepwater outlet to the Atlantic, the Cape Fear has dominated the history of southeastern North Carolina. Its wide, deep channel welcomed the first settlers to the area, served as a primary avenue of transportation and communication before the swampy lowlands along its banks were made accessible by bridges, opened the fertile farmlands and vast forests of the region, provided North Carolina with its first artery of maritime commerce, supplied the Confederacy with munitions and a variety of goods until the waning days of the Civil War, and gave the state its only modern, world-class port: Wilmington.

Its silt-laden waters begin their meandering, 320-mile run at the junction of the Deep and Haw rivers on the Chatham County-Lee County line. As it flows southeast through Harnett, Cumberland, and Bladen counties, the Cape Fear gains strength. Its high banks gradually flatten into marshy wetlands once the river makes its way into New Hanover and Brunswick counties.

It is at Eagles Island that the river gains its great power. Here, at “The Forks,” the waters of the Northeast and Northwest Cape Fear join forces to provide a deep, wide river for the Wilmington port facilities, located across the river from, and just south of, the battleship. The Cape Fear is the only coastal river in the state that is significantly affected by lunar tides far upstream. At Eagles Island, the tides average three to five feet.

Over the course of its long run, the Cape Fear drains more than 5,275 square miles. Its oblong basin is 200 miles long and as much as 60 miles wide. Had the river carved a course due east from its headwaters, it would empty into the Atlantic north of Cape Hatteras. However, geologic forces at work more than twenty-five thousand years ago and the rotation of the earth forced the river into its southeasterly route. It is the only river on the East Coast between the Hudson in New York and the Savannah in Georgia that reaches the Atlantic without being intercepted by a sound.

At Eagles Island, the majestic river begins its 30-mile final leg, widening up to 3 miles as it prepares to empty into the ocean. Although the balance of the tour parallels this course, the river will be mostly hidden from view.

To continue the tour, return to the intersection of U.S. 421 and U.S. 17/74/76 and proceed west on U.S. 17/74/76.

After 2 miles, you will cross the Brunswick River, a 5-mile-long branch of the Cape Fear. South of the bridge, this lazy tributary appears to be devoid of modern use, with only rotting pilings to mar its pristine appearance.

Yet few motorists who made their way into Wilmington in the 1950s and early 1960s will ever forget the spectacular sight they saw from this bridge. On the banks of the Brunswick River—where rice plantations once prospered—many of the survivors of America’s World War II cargo fleet were tied up as part of the nation’s postwar reserve fleet. For as far as the naked eye could see and beyond, hundreds of vessels—mostly aging Liberty ships, each measuring up to five hundred feet in length—stretched down the river. At its peak, the ghost fleet contained 649 ships and extended 2.5 miles along both banks, making it the second-largest merchant-ship graveyard in the world.

From August 8, 1946, when the SS John Boyce became the first ship towed to the basin, to February 27, 1970, when the SS Dwight Morrow was the last of the ships to leave the river, the massive reserve fleet was anchored within sight of the place where many of the ships were constructed: the North Carolina Shipbuilding Company at Wilmington.

Although the long, gray line of ships in the Brunswick River is nothing more than a memory now, those who saw it often catch themselves craning their necks as they drive along the river bridge, hoping they might catch one more glimpse of the spectacle known as “the Ghost Fleet of Wilmington.”

Just beyond the bridge over the Brunswick River, turn off U.S. 17/74/76 onto N.C. 133 at the small community of Belville. From Belville, N.C. 133 runs roughly parallel to the Cape Fear for a distance of approximately 10 miles. Until the early 1950s, when the military shipping installation at Sunny Point was built downriver, the ancient road linking Wilmington and Southport ran adjacent to the river. To accommodate the needs of the Sunny Point complex, N.C. 133 was moved inland, to the west.

Approximately 0.2 mile south of Belville, N.C. 133 offers a view of the Brunswick River. Through the trees, the dark, shimmering waters yield no clue that they once floated the great mothball fleet of Liberty ships. On the shoulder of the road opposite the river, a long row of eight historical markers erected by the North Carolina Division of Archives and History commemorates many of the significant events and persons in the long history of the Cape Fear.

The road makes its way past several modern subdivisions, then winds through forested savannas and swampy lowlands. Nearly a half-dozen large antebellum plantations once graced the banks of the river in this area.

Some of the old plantations vanished when they were consumed by larger plantations. For example, Lilliput, once held by Royal Governor William Tryon, and Kendall, the home of Major General Robert Howe—the highest-ranking American general of the Revolutionary War born south of Virginia—were absorbed by Orton Plantation. Nevertheless, sizable portions of four of the most historic of the river plantations are still intact.

Located 6.2 miles south of Belville, Clarendon remains one of the finest colonial rice plantations in the state. The plantation is situated on the eastern side of N.C. 133 but is not visible from the highway.

Established in 1730 on the site of the old Charles Towne settlement of the seventeenth century, the Clarendon grounds hold a wealth of historically significant artifacts. A powder magazine built in 1666 by early Cape Fear settlers is believed to be one of the oldest buildings in the state. Two canals on the property are of extreme importance. One, running a distance of several hundred yards through the ancient rice fields, is the only survivor of the numerous river canals once found on the plantations. The other canal, a fifty-foot-wide waterway along the river, was dug by Indians as a time-telling device. It is so perfectly oriented that the sunrise at the summer solstice still ascends dead center in the canal. Some historians and scientists contend that this canal represents the first calendar ever used in the Cape Fear region.

Clarendon was acquired after the Revolutionary War by Governor Benjamin Smith. In 1834, the Watters family came into ownership of the plantation and erected a magnificent two-story plantation house, which still stands on a high bank at the end of a magnificent lane of yaupon and silver maples. It was in this house that renowned author Inglis Fletcher penned her famous historical novel Lusty Wind for Carolina.

Unfortunately, Clarendon is not open to the public.

Town Creek, a long, scenic waterway which flows from the center of Brunswick County into the Cape Fear, intersects N.C. 133 approximately 1.5 miles south of Clarendon. On the northern banks of the creek are the ruins of perhaps the oldest plantation of the Lower Cape Fear: Old Town Plantation.

Colonel Maurice Moore was granted this thousand-acre site in and around the mouth of the creek in 1725. The massive plantation house was constructed several years later. Located near the mouth of the creek, the Old Town graveyard contains some tombs of the colonists who settled the area in the 1660s.

A private, unpaved road leads from the highway into the heart of Old Town Plantation.

One of the most majestic colonial plantations in all of America lies on the banks of the Cape Fear 0.3 mile south of Town Creek, at the intersection of N.C. 133 and S.R. 1518. Pleasant Oaks, originally named The Oaks, was established from a 1725 land grant to the Moore family. Its stately entrance—magnificent wrought-iron gates enclosed by white brick facades—is similar in appearance to, and often confused with, that of Orton Plantation, the famous plantation next door.

From the entrance to Pleasant Oaks, a mile-long lane winds through a wooded area of white oaks, then crosses a dam that forms an artificial cypress lake. Beyond the lake, the road makes its way up a slight hill to the antebellum plantation house, located at the junction of Town Creek and the river.

The fields and gardens of Pleasant Oaks have long enjoyed a reputation for their productivity and beauty. In the decade before the Civil War, the plantation earned the distinction of producing the finest and largest-grain rice in the world. Its camellia gardens later came to be considered among the most beautiful in the nation.

Today, a 2-mile avenue of live oaks, still regarded as one of the most picturesque lanes in all the South, leads to the gardens. Several decades ago, the plantation was open to the public, but it is now closed.

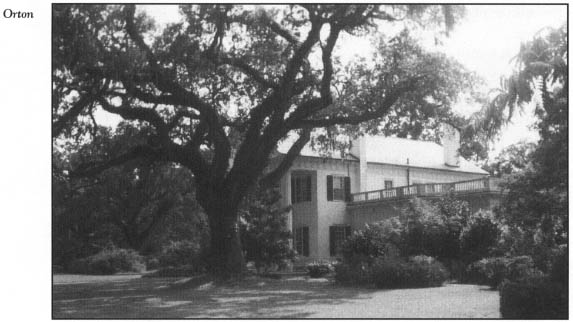

Continue 5.3 miles south from Pleasant Oaks to see one of the best-known colonial-era showplaces in the United States. Orton, that ancient estate of the pre-Revolutionary War era, has survived the ravages of time, war, and economic change to emerge as a magnificent historic portrait of coastal North Carolina.

To reach Orton, turn off N.C. 133 onto S.R. 1529. The entrance is marked by massive gray stone pillars surmounted by eagles with outspread wings. This splendid 10,000-acre estate boasts the only surviving colonial mansion on the Cape Fear River and some of North Carolina’s most beautiful gardens.

Orton was born of the efforts of the Moore brothers—Maurice, James, Roger, and Nathaniel—who settled in the area in the first quarter of the eighteenth century, after leading efforts to suppress uprisings by local Indians. In 1725, Roger Moore was granted an enormous tract of land along the river just north of the site of Brunswick Town. There, he established a lavish plantation, which he named Orton for the village of the same name in the Lake District of England, the ancestral home of the Moore family.

Roger Moore wasted no time in erecting a plantation house, choosing a site on a bluff separated from the river by picturesque meadows and marshland. Indians subsequently attacked and destroyed the original structure. Moore rebuilt in 1730, and it was from this second plantation that the existing mansion emerged.

Because his estate was located in the northernmost section of the lucrative rice-growing region, Moore built dikes to flood the fertile marshes for rice cultivation. His leadership, wealth, penchant for opulent living, and hospitality brought him a large measure of fame. Consequently, he became known far and wide as “King Roger.”

By 1880, the estate lay in virtual ruin. The great domain of King Roger was about to be reclaimed by the coastal wilderness.

Colonel Kenneth M. Murchison, a Confederate veteran, stepped forward in 1884 to purchase the plantation house and grounds. He promptly set out to recapture Orton’s former grandeur.

Orton entered the modern age in 1905 at the death of Colonel Murchison. Dr. James Sprunt purchased the estate for his wife, Luola Murchison Sprunt, Murchison’s daughter. Through the vision and imagination of Mrs. Sprunt, work on the majestic, colorful gardens—enjoyed by thousands of visitors each year—began in 1910. She was also responsible for adding the wings on either side of the plantation house.

When Dr. Sprunt died in 1924, Orton passed to his son, James Laurence Sprunt. At that time, the plantation was accessible only via the river. Sprunt promptly opened the Colonial Road to Wilmington, thereby setting the stage for the birth of the tourism industry at the plantation. In the late 1920s, the grounds and gardens were opened to the public.

Visitors to the estate may be able to hear the thunder of the mighty Atlantic on tranquil days, as waves culminate their 3,000-mile journey by crashing upon the beaches just across the river.

Countless tides have rolled in since Roger Moore rebuilt his home on the river bluff. Despite extensive modifications and additions in 1840 and 1910, critics have acclaimed the house as one of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture in the country. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the mansion at Orton is one of the few houses on the North American continent that has been continuously occupied since 1730. At present, the house is the private residence of the Sprunt family. Nonetheless, visitors strolling the gardens and grounds are treated to a splendid closeup view of the exterior of the magnificent structure.

Its classic lines and postcard-perfect appearance have made the mansion one of the most recognizable landmarks in the state. It is little wonder why artists, moviemakers, and writers have used Orton as a setting for their work. In 1954, the mansion was selected as the subject of a mural in the dining room of the famous Blair House in Washington, D.C. Orton also served as a backdrop for the Stephen King movie Firestarter, in which a fake facade was used to give the illusion that the house was being consumed by fire. Renowned novelist James Boyd set his classic work, Marching On, at Orton.

Of the historic plantations of the Cape Fear region, only Orton opens its grounds and gardens to the general public.

Your drive down the entrance avenue of towering, ancient oak trees festooned with Spanish moss leads past an expansive, dark lake rimmed by dogwoods, Indian azaleas, and shrubs to the storybook gardens. Park in the lot adjacent to the ticket office, just south of the mansion.

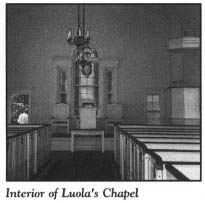

Near the parking lot, a brick path flanked by white pines leads to Luola’s Chapel, a gleaming white chapel designed as a memorial to Luola Murchison Sprunt, who died in 1916. Simple yet beautiful in design, this private house of worship seats 150.

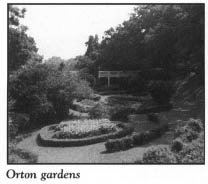

From the chapel, a walking tour leads to the Radial Garden, the first of many gardens on the estate. Spread about the sweeping green lawns and shaded by stately live oaks, magnolias, and pines, these gardens showcase some seventy-five species of ornamental plants.

At various points along the garden tour are man-made structures of special interest. Two white, frame belvederes look out over the old rice fields, now leased to the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission as a wildlife refuge, and over a slate-blue lagoon. North of the belvederes, a bridge crosses the water and offers a spectacular view of Orton’s northwestern lagoon. This lovely vista is known as “the Water Scene.” During the heat of the summer months, alligators can often be observed swimming in the lagoon or sunning on its banks.

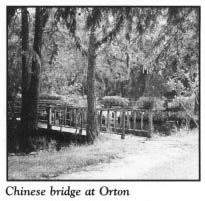

On the western side of the gardens, an unusual Chinese bridge zigzags its way over the fringes of the lake and a waterway leading to the lagoon. It was Robert Swan Sturtevant, the famed landscape architect who laid out the modern gardens at Orton, who tackled the problem of getting garden visitors from one side of the lake and waterway to the other. The builders of this unusual bridge have long claimed that its design prevents evil spirits from crossing, since spirits can only walk in a straight line.

The path loops around the northern edge of the gardens to the colonial-era cemetery where King Roger Moore is buried. Moore’s tomb dominates the ancient family burial ground.

Once you have enjoyed your walk through Orton Plantation, return to your car and continue driving in your original direction on S.R. 1529. After 0.8 mile, turn left, or east, on S.R. 1533 for a 1.1-mile drive to the ruins of Brunswick Town, on the banks of the Cape Fear.

Museum artifacts and the foundations of eighteenth-century buildings scattered about the riverside landscape are the only tangible reminders of the ancient port that was once the leader in colonial North Carolina. Brunswick Town was the setting for the first armed resistance to British colonial rule in the American colonies, yet by the time independence was won fifteen years later, it was virtually a ghost town. Eighty years later, when the South fought to end the union born of the American Revolution, a mighty earthwork fortress, Fort Anderson, was constructed on the old town site as part of the defense system for the Cape Fear region.

Now a state historic site, Brunswick Town affords visitors an opportunity to walk among the stone foundations of dwellings where royal governors once lived and climb upon the well-preserved mounds of the Civil War fort.

Brunswick Town was the creation of the enterprising Moore family, who in 1726 set aside a 320-acre parcel for the establishment of a town to handle the export of vast quantities of naval stores. In 1731, the fortunes of the fledgling town received a boost when Brunswick Town was declared one of the five official ports of entry in the province. Over the next century, Brunswick Town was one of the leading seaports in North Carolina. For a portion of that period, more than 70 percent of the world’s naval stores were shipped from the harbor here. Mariners from the world over called at the Cape Fear port, giving the town a cosmopolitan atmosphere.

But even as the port was enjoying commercial success, there were clouds on the horizon. In 1740, the town lost its status as county seat to an upstart river village to the north: Wilmington. Eight years later, the vulnerability of Brunswick Town to foreign attack was made evident when, during the War of Jenkins Ear—which started when Spanish soldiers captured the brig Rebecca and cut off the ear of an Englishman named Jenkins—three Spanish sloops invaded and plundered the town.

When Brunswick County was created in 1763, Brunswick Town again became a county seat. And although the port never had a population of more than four hundred, it was home to men whose names are etched on the honor roll of early North Carolina history. Among its residents were three Revolutionary War generals, three royal governors, and a justice of the United States Supreme Court.

On the morning of February 21, 1766, less than four months after the Stamp Act went into effect, Brunswick was the setting of one of the most dramatic moments in the years leading up to the American Revolution. Cornelius Harnett, a local leader who grew up in Brunswick Town, and some 150 armed citizens known as “the Sons of Liberty” encircled customs officials and other agents of the Crown at Brunswick Town and watched triumphantly as each took an oath to refrain from issuing any stamped paper in North Carolina.

George Davis, the gifted nineteenth-century statesmen from Wilmington who served as attorney general of the Confederate States of America, lamented the lack of significance accorded the confrontation at Brunswick in 1766: “This was more than ten years before the Declaration of Independence and more than nine before the Battle of Lexington, and nearly eight before the Boston Tea Party. The destruction of tea was done at night by men in disguise. And history blazoned it, and New England boasts of it, and the fame of it is world wide. But this other act, more gallant and more daring, done in open day by well-known men, with arms in their hands, and under the King’s flag—who remembers it, or who tells of it?”

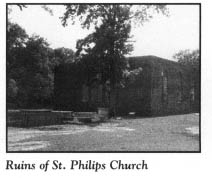

On May 24, 1768, St. Philips Church, planned as far back as 1745, was consecrated in a dignified ceremony at Brunswick Town. Its thirty-three-inch-thick exterior walls, containing four slender, arched windows on each side, still stand today.

As the winds of war began to sweep over the Cape Fear region in the 1770s, most of the inhabitants of Brunswick Town—already dispirited by the destructive hurricanes that frequently hit the area, the high humidity, and the malaria-infested swamps—abandoned the port. On the heels of this exodus, the British attacked in 1776, and in a cruel twist of fate, the town that provided the initial spark of the American Revolution was razed.

A few families returned after the war to live among the ruins, but for all intents and purposes, Brunswick Town was finished. On a visit to the area in 1804, Bishop Francis Asbury, the renowned Methodist circuit rider, noted that Brunswick Town was nothing more than “an old town, demolished houses, and the noble walls of a brick church, there remains but four houses entire.”

By 1832, the town was completely devoid of humanity. Title to the site reverted to the state. In 1845, the late, great port of Brunswick Town was conveyed to the owner of Orton Plantation for the sum of $4.25.

Fifteen years later, as the nation stood on the precipice of the Civil War, the ruined buildings of Brunswick Town were hidden in a veritable jungle. To protect the vital port of Wilmington, the Confederate government constructed an earthwork fortress on the ruins of Brunswick Town in 1862. The fort consisted of two five-gun batteries and numerous smaller emplacements set along the giant sand banks, which towered as high as twenty-four feet. Its original name, Fort St. Philip, was quickly changed to Fort Anderson, in honor of General Joseph Reid Anderson, an early commander of North Carolina coastal defenses during the Civil War. Fort Anderson remained in Southern hands until the waning days of the Confederacy.

For almost 90 years after the war, Fort Anderson and Brunswick Town were abandoned to the forces of nature. In 1955, the 119-acre tract was dedicated as a state historic site. Following extensive archaeological work, ground was broken for a combination visitor center and museum in 1963.

With archaeologists assigned to the site on a permanent basis, important research and excavations have been carried out on a daily basis over the past thirty years. The visitor center/museum features interesting displays of many of the artifacts extracted from the ruins.

More than sixty excavated foundations can be seen during the pleasant walking tour of the historic site. Stop at the visitor center to pick up a printed tour route.

From the visitor center, the walking tour proceeds across the parking lot to the most identifiable ruins of the site—those of St. Philips Church. Within the church’s roofless walls are twelve graves, including those of Royal Governor Arthur Dobbs, Justice Alfred Moore of the United States Supreme Court, and the infant son of Royal Governor William Tryon.

From the ruins of the church, the walking tour proceeds south along old Second Street and veers sharply east toward the river, passing the ballast-stone foundations of a number of dwellings erected in the first half of the eighteenth century.

Near Brunswick Pond, the walking tour divides. The northern route follows Front Street to the well-preserved remains of Fort Anderson, where the path runs along the top of Battery B. Near the parking lot, this path intersects Brunswick Town Nature Trail, a short route that winds its way along the banks of Brunswick Pond. During the summer months, this pond, covered with green vegetation, often resembles a swamp. It is the remnant of a spring-fed swamp located in the heart of the town during colonial times.

Admission to Brunswick Town State Historic Site is free. A public picnic area is located north of the visitor center/museum.

After you have enjoyed the historic site, retrace your route to Orton Plantation and turn west onto S.R. 1530, the 0.3-mile connector road to N.C. 133. Turn south onto N.C. 133 for a 7.3-mile drive that runs parallel to the Military Ocean Terminal at Sunny Point, the nation’s largest shipper of weapons, tanks, explosives, and military equipment. This lifeline for the defense of the free world is situated on an 8,502-acre site.

When the decision was made to construct the nation’s only military terminal devoted entirely to ammunition, experts conducted a meticulous search for a relatively isolated spot close to inland transportation. The site at Sunny Point was determined to be ideal, and in 1951, the $26-million, four-year project was commenced.

To minimize the effect of a potential explosion at the facility, a maze of bunkers as high as forty feet has been constructed around the area where hazardous cargo is held and handled. Because of the dangerous and confidential nature of the activities here, access to the installation is highly restricted. The base entrance is located at the junction of N.C. 133 and N.C. 87.

At the entrance to Sunny Point, turn north off N.C. 133 onto N.C. 87 for a 2-mile drive to Big Lake, located in the heart of Boiling Spring Lakes, the youngest of the towns on the tour.

More than fifty crystal-clear spring-fed lakes in a variety of sizes and shapes dot the sixteen thousand acres of pinelands encompassed by this sprawling, sparsely populated community. Since two enterprising businessmen purchased the enormous tract thirty-five years ago with a dream of creating a large resort and retirement development, an assortment of modest residential dwellings, retirement homes, and vacation cottages has been constructed along the 110 miles of roads that weave their way through the forests and around the lakes and ponds.

Unlike most of the lakes, three-hundred-acre Big Lake, the town’s center-piece, is man-made, having been constructed in 1961. Fifteen years later, the Corps of Engineers threatened the vitality of the town when it drained the lake to prevent damage to the railroad supplying Sunny Point and the Brunswick Nuclear Plant at nearby Southport. The lake has since refilled.

Long before the first white settlers arrived in the area, Indians made their way to the site of Boiling Spring Lakes, where they refreshed themselves with the water from the springs. Although the waters were neither curative nor hot, they provided an oasis for the Indians on their annual hunting and fishing pilgrimages to the sea. From the days of the Indians, a popular local legend evolved that whoever drank from the effervescent springs would always return.

In the 1950s, Bill Keziah, noted Southport journalist and self-styled publicist for the Cape Fear area, “discovered” a spring long known to some locals as Bouncing Log Spring, which spews forth 42 million gallons of water every day. To enhance the beauty of the bubbling spring, the developers of Boiling Spring Lakes decided to construct a four-foot-high wall around Bouncing Log Spring. No sooner had the wall been built than the natural fountain stopped flowing. Within a few hours, however, a full flow of water began bubbling forth from the ground fifteen feet from the well.

A railroad bridge constructed in 1988 closed the only paved road leading to Bouncing Log Spring. Now, the fountain bubbles forth in a junglelike thicket of scrub oak and ivy accessible only by a maze of unpaved roads. Pesky biting flies swarm about the site, which is marked by a wooden sign.

Retrace your route from Big Lake to the junction of N.C. 87 and N.C. 133, where the tour ends. Southport is located 4 miles south.