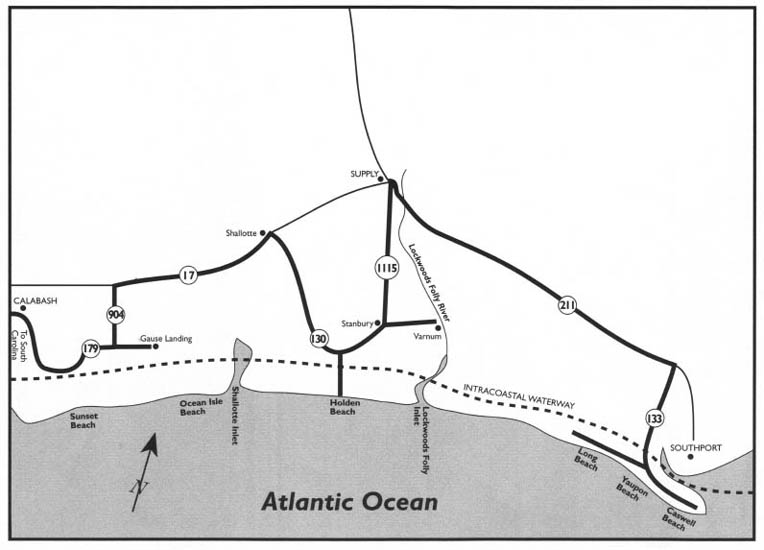

This tour begins at the intersection of N.C. 133 and N.C. 211 approximately 2 miles west of Southport. Drive south on N.C. 133.

This tour begins with a visit to Oak Island and its three resort communities: Yaupon Beach, Long Beach, and Caswell Beach. It then threads its way back and forth between mainland villages and the remaining Brunswick Islands, moving from Varnum to Holden Beach, from Shallotte to Isle Beach, and from Gause Landing to Sunset Beach. Back on the mainland, it visits Calabash before ending near the former site of historic Boundary House.

Among the highlights of the tour are the story of Hurricane Hazel, the ship-wrecks in Lockwoods Folly Inlet, the Oak Island Lighthouse, Fort Caswell, the healing waters of Shallotte Inlet, and the story of Mrs.Calabash.

Total mileage: approximately 93 miles.

As you make your way toward the Atlantic, you will pass a variety of businesses and service facilities that have proliferated over the past several decades in response to the burgeoning tourism industry on Oak Island, the largest of the Brunswick County islands on this tour.

After 2.8 miles on N.C. 133, the mainland ends at the Intracoastal Waterway, located just south of the Brunswick County Airport, a small airfield with paved, lighted runways.

When the $3.6-million bridge to Oak Island was completed over the Waterway in 1975, it was one of the first modern high-rise bridges constructed to replace the romantic, but antiquated, drawbridges that once linked most of the barrier islands to the mainland. At the crest of the 5,000-foot, arched span, you will have a magnificent panorama of the Intracoastal Waterway, Oak Island, and the Cape Fear River. A night crossing offers the comforting beam of the Oak Island Lighthouse.

Erroneously described as a peninsula by some geographers, Oak Island is the western landmass at the mouth of the Cape Fear River. Separated from Bald Head Island, to the east, by the Cape Fear, separated from Holden Beach, to the west, by Lockwoods Folly Inlet, separated from Southport and the Brunswick County mainland, to the north, by the Elizabeth River, and bordered on the south by the vast Atlantic, Oak Island is truly an island. As early as 1770, it was shown as such on the Collet map of North Carolina.

Apparently named for the live-oak trees that grow abundantly on its 14-mile-long landscape, Oak Island was relatively free of human habitation until well into the nineteenth century. Except for a handful of farmers, fishermen, shipwreck victims, and fugitives from justice, there were no permanent residents on the island until Fort Caswell was completed at the extreme eastern end of the island in 1838. Even then, the fort maintained a relatively small garrison until the Civil War.

Despite its strategic location at the mouth of the Cape Fear, the island saw limited action during the war. Three island forts were garrisoned by Confederate troops. Fort Caswell was wrested from Union control once North Carolina joined the Confederacy. To supplement Caswell, the Southern forces put up two small earthwork fortifications—Forts Campbell and Shaw—farther down the island. Nothing remains of those two makeshift outposts.

Following the Civil War, Fort Caswell was manned during irregular periods through World War II. Nonetheless, Oak Island did not begin to attract a significant population until the latter stages of the Great Depression. A pontoon bridge was put in place in the 1930s, thus providing a direct connection to the mainland for the first time. Improved access aided in the development of a vacation resort in and around Fort Caswell in the years preceding World War II. About the same time, E. F. Middleton of Charleston, South Carolina, purchased much of the island west of the Fort Caswell development as part of vast Brunswick County land acquisitions by a pulp-wood concern. His employers found the island to be of little value to their business, so Middleton arranged to take title to the Oak Island property for speculative purposes. The beach towns of Long Beach and Yaupon Beach were subsequently built on this property in the 1950s.

Immediately prior to World War II, the first bridge to the island was replaced by a concrete drawbridge. Unfortunately, the war intervened before the island’s resort potential could be realized. The drawbridge succumbed to a runaway barge on September 7, 1971. The old road approaches to that bridge are visible from the modern bridge.

Yaupon Beach, squeezed between Caswell Beach and Long Beach, begins where the bridge ends and serves as the gateway to the island. Although it plays second fiddle to Long Beach in area and population, Yaupon Beach boasts approximately a thousand permanent residents.

From the southern end of the bridge, proceed 0.7 mile south to where N.C. 133 ends at the traffic light. Continue south on Caswell Beach Drive for 0.3 mile, then turn west onto Ocean Drive.

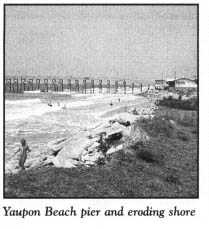

Here, the Yaupon Beach oceanfront offers visible evidence of the erosion to which many of the barrier islands of the North Carolina coast are exposed. Coastal geologists contend that erosion is a layman’s term for the natural migration of barrier islands toward the mainland. The strand at Yaupon Beach is scarred by numerous tree stumps—graphic reminders of a time when ancient maritime forests stood where beachcombers now frolic.

One of the landmarks on Ocean Drive is the Yaupon Beach Pier, the newest and tallest ocean fishing pier on the North Carolina coast. Completed in 1993 at a cost of half a million dollars, the pier replaced a 1955 structure damaged beyond repair by Hurricane Hugo. The pier is located at the end of Womble Street after 6 blocks on Ocean Drive.

After 0.5 mile on Ocean Drive, turn north on Crowell Avenue. A drive along this short residential street reveals the abundant forest canopy that distinguishes Oak Island from most of the other barrier islands of North Carolina. Although trees reach the strand only at Yaupon Beach, where the island is just over 2 miles wide, pine forests cover much of the northern half of the island.

Turn west off Crowell Avenue onto Yaupon Drive, which becomes Oak Island Drive as it makes its way to Long Beach and the western end of the island.

Tourists who come to Oak Island and its sister Brunswick Islands in search of the glitz of Myrtle Beach are disappointed. On these heavily developed barrier islands, the rush to modernity has been tempered by an abiding respect for a slow-paced lifestyle. During the peak of each summer season, upwards of fifty thousand vacationers flock to Oak Island each week in search of sea, sun, and fun at a resort lacking high-rise hotels, posh restaurants, large shopping complexes, and sprawling amusement parks.

After 4.5 miles, turn south off Oak Island Drive onto Middleton Street in Long Beach. Named for the man who was instrumental in the development of this resort community, the road is the only sound-to-sea street on the western quarter of the island.

It is 0.3 mile on Middleton to the Long Beach strand. Midway, a bridge spans Big Davis Canal, a wide, scenic tidal creek that runs the length of the western half of Oak Island, thus splitting the island into two distinct bodies. When viewed from the air or from a map, the island resembles the head of a giant alligator.

Middleton Avenue ends at Beach Drive, a long oceanfront road lined with rows of brightly painted beach cottages of all shapes and sizes. Turn west onto Beach Drive.

Although Long Beach is in its infancy compared with the historic settlements of the Cape Fear area, it has a year-round population of thirty-three hundred, making it the second-most-populous town in Brunswick County. Most of the permanent residents do not live in the oceanside retreats on Beach Drive. Rather, they live on the sheltered northern side of the island.

On the 3.5-mile drive on Beach Drive to the western end of the island, you will notice several tall, vegetated sand dunes. These survive as mute reminders of the numerous dunes and sand hills that dominated the island landscape prior to resort development. Before the bulldozer leveled most of them, these tall dunes were used as navigational guides and landmarks.

After World War II, Oak Island seemed destined to take its place as the state’s newest barrier-island resort. In the early 1950s, E. F. Middleton and his associates began selling lots on the strand at the future sites of Long Beach and Yaupon Beach. When the town of Long Beach was incorporated as the first municipality on Oak Island in 1953, there were at least a dozen families living permanently on the island.

But the development of Oak Island was temporarily blocked by a catastrophe of immense proportions. In the early-morning hours of October 15, 1954, the North Carolina coast experienced the ultimate storm when Hurricane Hazel unleashed her devastating power on the Cape Fear coast. On that fateful day, North Carolina lost every one of its fishing piers.

No North Carolina coastal community was spared the wrath of Hazel, but the most complete destruction occurred at Long Beach. On October 14, 1954, the infant resort boasted 357 houses.

One day later, only 5 were left.

The Capel House, one of the two frame houses that survived, is still visible today high atop Folly Hill. Easily identifiable as the tallest sand dune on the island, Folly Hill is located on the northern side of Beach Drive approximately 2 miles west of Middleton.

The sheer terror of a storm of the magnitude and intensity of Hazel has not often been recorded, because few people who stay to “ride out” hurricanes survive. Two such people survived Hazel on Long Beach.

Connie Ledgett, a seventeen-year-old newlywed, and her twenty-one-year-old husband arrived at Long Beach for their honeymoon in the early-evening hours of Thursday, October 14, 1954. Although they had heard news reports of a hurricane in the Bahamas, they did not give the storm much thought.

During the wee hours of the next morning, the newlyweds were awakened by a howling wind. From their third-row cottage, they could see the ocean rising above the high dunes. As conditions worsened, they realized that they had to leave the island.

By the time their car was loaded, the ocean had breached the dunes and spilled onto the road. When water reached the fenders of the car, they abandoned the vehicle and made it back to their cottage. From there, they waded in waist-deep water to a two-story apartment house and forced their way into the structure.

They survived the first half of the hurricane in a second-floor apartment. Gradually, the raging ocean reached their second-story window, and waves broke against the building. Their temporary place of refuge rocked like a boat. Connie Ledgett could hear it breaking up below her.

Recognizing that their best chance for survival was to get out of the building, the newlyweds attempted to float a chest of drawers out the window, but a wave carried it away. Finally, they put a mattress out the window, and Connie, who could not swim, lay on it while her husband held onto the straps. They also used a piece of house wall that floated by to increase their buoyancy.

Wind and water carried the couple to the tops of some scrub oaks that were twenty feet high. From their vantage point, they saw the kind of sights few people have lived to tell about. Floating houses crashed into each other. They saw several other people but could not reach them or communicate with them because of the fury of the storm. They could see nothing of the landscape, as Oak Island was completely inundated with water.

Finally, the storm began to diminish and the water receded. The terrified newlyweds climbed down and made their way off the island. Their cottage had been destroyed, but the apartment which had provided temporary refuge was one of the five surviving buildings. However, it had been moved some seventy-five feet, and the second floor had given way.

Days later, Connie’s parents found the refrigerator from their daughter’s cottage in a marsh, where it had floated during the storm. Inside was the newlyweds’ wedding cake.

Although the storm cut an inlet through the island near Folly Hill, it did not dampen the enthusiasm of developers and potential property owners. Very little time passed before work was under way to re-form dunes that had been leveled by the storm surge. Bulldozers closed the inlet; streets were cleared of sand and debris and were repaved; lots were surveyed and boundary lines were reestablished; and the basis of the modern resort towns of Oak Island was created.

Beach Drive forks near the western end of the island. Take the right fork and drive to the parking lot at the end of the road. This road once circled around the end of the island, but in the late 1970s, Hurricane David and other coastal storms destroyed such a large portion of it that repairs were never effected.

Many visitors leave their vehicles at the parking lot and take the short walk across the sand flats to Lockwoods Folly Inlet, which separates Oak Island from Holden Beach. Shell collectors, beachcombers, and fishermen are attracted to this scenic, undeveloped spit of land, known locally as “The Point.”

From The Point, Holden Beach is easily visible to the naked eye. Although the two islands are separated only by a relatively narrow inlet, the distance between them by roadway is more than 20 miles.

The name Lockwoods Folly first appeared on the Ogilby map of 1671. It is said to have originated with a man named Lockwood who built a boat up what is now Lockwoods Folly River, only to discover that it was too large to float downriver. Ultimately, the vessel was abandoned and fell to pieces.

Four Civil War shipwrecks have been discovered in the shallow waters of Lockwoods Folly Inlet near The Point. Two of them—the Ranger and the Bendigo—are visible above the surface at low tide. When the water level is extremely low, intrepid swimmers from Long Beach and Holden Beach wade to the wrecks. Both ships were steamers that were pressed into service as blockade runners.

Built on the famous Clyde River in England, the five-hundred-ton Bendigo was set afire in the inlet on January 4, 1864, to avoid capture by pursuing Union naval forces. The inlet floor around the wreck is littered with the hull, the engine, and some machinery.

A week after the Bendigo met her demise, the double side-wheeler Ranger, loaded with Austrian rifles and carpentry tools, was set afire by Confederate ground forces at Oak Island to prevent it from falling into the hands of the enemy.

Wreckage of a third blockade runner, the wooden-hulled steamer Elizabeth, lies below the surface 1,250 feet south of the Bendigo. Also nearby and hidden below the waters is the wreckage of the USS Iron Age, one of the few Union vessels sunk while engaged in blockading activities during the entire war.

From “The Point,” turn around and drive east on Beach Drive.

From time to time, shifting sands reveal the wooden skeletons of several unknown ships on the Long Beach shoreline near Thirteenth Place West and Third Place West. Farther east, the Long Beach Scenic Walkway, located just off Beach Drive at Twentieth Place East, offers unspoiled vistas of Davis Canal as it winds its way through cordgrass and marshes.

After 7 miles on Beach Drive, turn left, or north, onto Fifty-eighth Street. Follow Fifty-eighth to Oak Island Drive and turn right, or east. Oak Island Drive changes to Yaupon Drive along the 3-mile drive to the traffic light at Caswell Beach Drive back in Yaupon Beach. Turn southeast onto Caswell Beach Drive and proceed 2 miles to the final stop on Oak Island—Caswell Beach, the smallest and youngest of the three resort municipalities.

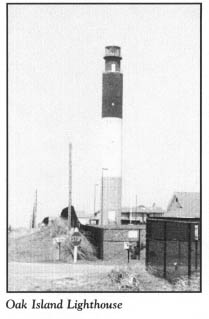

Incorporated in 1975, Caswell Beach has several hundred permanent residents. It is the home of two of the most historic landmarks on Oak Island—the Oak Island Lighthouse and Fort Caswell, both located at the eastern end of the island near the mouth of the Cape Fear River.

Located adjacent to the entrance to Fort Caswell, and towering over the Oak Island Coast Guard Station, the Oak Island Lighthouse is the newest and southernmost lighthouse on the North Carolina coast. Constructed in 1958 to mark the entrance to the Cape Fear River, the 169-foot tower was the first lighthouse to be constructed in the Fifth Coast District—which includes Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina—in fifty-four years. Due to technological improvements in navigation since World War II, this lighthouse is likely to be one of the last constructed along the coast of the United States.

In appearance, the Oak Island Lighthouse is the ugly stepsister of the romantic old lighthouses standing guard over the North Carolina waters to the north. It resembles a tall, slender silo decorated in drab colors. Designers sacrificed aesthetics for utility and economy when drawing the plans for the tower at Caswell Beach.

When construction began in 1957, the builders were forced to excavate 125 feet underground to find a rock foundation strong enough to support the tower. In order to eliminate the need for future painting, colors were mixed into the wet concrete of the three sections. Gray was used for the bottom section, white for the middle, and black for the top. Now, a third of a century later, the harsh coastal elements have caused the colors to fade.

On May 15, 1958, the light was put into operation. For many years thereafter, the 1,400,000-candlepower beacon was rated the second most brilliant in the world, with only a French lighthouse on the English Channel having a more powerful beam. At present, the main light features a four-light rotating fixture working in conjunction with twenty-four-inch parabolic mirrors and quartz bulbs. Visible up to 19 miles at sea, the light flashes four times every ten seconds. So intense is the heat it generates that Coast Guard personnel who maintain the facility must wear protective clothing while working in the aluminum-frame beacon room.

The lack of eye appeal of the concrete tower can be partly attributed to its uniform diameter of eighteen feet. Despite its relatively narrow base, the lighthouse is a sturdy structure. By design, it sways as much as three feet in a sixty-mile-per-hour wind.

Although the lighthouse is a favorite of painters and photographers, only authorized personnel are allowed inside the tower, which has 134 steps and a narrow ladder leading to the beacon. The grounds are open to the public from four o’clock in the afternoon to sunset Monday through Saturday, and from noon to sunset on Sunday.

Located behind a cottage between the lighthouse and the entrance gate to Fort Caswell is the brick foundation of an old lighthouse, one of two constructed on the island by the United States Treasury Department in 1849 to aid ships entering the river. Rebuilt in 1879, the rear beacon operated until 1958, when its wooden tower burned.

On the oceanfront directly across from the old lighthouse, a former United States Lifesaving Station has been converted into a private residence.

Fort Caswell, that ancient military bastion built when the nation was a half-century old, survives on the extreme eastern end of Oak Island. Even though this outpost was considered one of the strongest fortifications in the nation at the time of its construction, it never saw extensive military action during its 140 years of service as a vital link in America’s coastal defense system.

The War of 1812 exposed the extreme vulnerability of the American coast to attack by foreign invaders. In an attempt to fortify the major coastal inlets, the federal government initiated the postwar construction of sea fortifications. From this building program came Forts Caswell, Macon, Moultrie, and Sumter in the Carolinas.

In 1824, the government purchased 2,755 acres on the eastern half of Oak Island for a military reservation to protect the entrance of the Cape Fear. A year later, on March 2, 1825, Congress appropriated funds for the project. However, plans were not drawn until 1826, and actual construction did not begin until 1827.

By the time the project was completed in 1838, numerous cost overruns ballooned the final price tag to $473,402, almost four times the original estimate. Twelve years of work culminated in an enclosed pentagonal fort with a two-tiered escarpment flanked by gun galleries providing fire down the moat. It also featured sixty-one guns bearing on the channel, as well as a few small guns for land defense. The inner citadel contained barracks, officers’ quarters, storerooms, and an armory.

On April 18, 1833, in the midst of the laborious construction project, Fort Caswell was named in honor of Richard Caswell (1729–1789), the hero of the Battle of Moores Creek Bridge and the first governor of the independent state of North Carolina.

Following World War I, the entire reservation—save fifty-seven acres reserved for Coast Guard use—was declared government surplus and was sold to a group of North Carolina and Florida businessmen. But with the Great Depression and World War II waiting in the wings, the elaborate plans for the development of a port and resort town at Fort Caswell never came to fruition.

Less than a month before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the federal government reclaimed the 248.8 acres containing Fort Caswell for use as a submarine patrol base. After the war, the site was once again declared surplus property. Plans to include the fort in the state parks system never got off the drawing board.

On September 17, 1949, following their abandonment by the military, the buildings and grounds were acquired by trustees of the North Carolina Baptist Convention for the sum of eighty-six thousand dollars. Since then, the Baptists, while cognizant of the historic significance of Fort Caswell, have been hard at work turning swords into plowshares at this time-honored spot, using it as a spiritual retreat and recreational center. A security station is located at the retreat entrance on Caswell Drive. Visitors interested in seeing the site are permitted to enter the grounds.

The most visible remains of the fort are the inner walls. There is scant evidence of the foundation of the cross-shaped citadel which stood inside the walls. One of the three entrances into the rooms under the fort is preserved.

All of the gun emplacements and much of the concrete that made up the seven batteries constructed between 1896 and 1905 survive. Most of the buildings on the grounds are former military structures constructed to meet the needs of troops during the two world wars.

After you have enjoyed Fort Caswell, retrace your route on Caswell Beach Drive to its junction with N.C. 133 in Yaupon Beach, then follow N.C. 133 back to where this tour started at the intersection with N.C. 211 near Southport. Proceed northwest on N.C. 211 for a 13-mile drive through a rural, relatively undeveloped, forested section of Brunswick County. Throughout the eighteenth century and until the Civil War, these pine forests fueled the area’s naval-stores industry, which was a world leader.

Visitors and residents alike are mystified by the strange, rumbling booms that shake cottages and other buildings along the beaches of southeastern North Carolina. No one is sure what causes them, where they come from, or when they will come again. Residents say that while the sounds bear a similarity to thunder or a sonic boom, they are different from both. It is almost universally agreed that they emanate from the ocean. The booms last two or three seconds and are strong enough to rattle windows and shake articles off shelves. Most often, the mysterious rumblings occur in the fall and spring. On occasion, they shake the coast more than once a day. Sometimes, they strike several days in a row, while at other times, weeks pass without a single one.

There is no record of how long this weird commotion has been going on. Grandparents in the area claim that their grandparents, who lived long before the advent of airplanes, remembered the booms, so the sonic-boom theory has been thoroughly discounted.

Because all attempts to unravel the mystery have failed, many residents of the Brunswick coast are satisfied to explain the phenomenon with the legend of the “Seneca Guns.” According to this legend, the Seneca Indians, who were driven from the area by white settlers, are now returning with the white man’s own weapons for revenge.

Legend aside, seismographic instruments have indicated that the reverberations are not caused by earthquakes. Conventional wisdom is that they have a military connection. Despite denials by officials at nearby Sunny Point Ocean Terminal and other military personnel, many area residents compare the sounds to the thunder of artillery or depth charges. Some scientists believe that it is more than coincidence that the booms seem to take place when there is military traffic in the area.

Twelve miles into your 13-mile drive through the Brunswick County countryside, you will cross the black waters of the Lockwoods Folly River, one of the most beautiful rivers in southeastern North Carolina.

Just north of the river bridge at the village of Supply, turn south onto S.R. 1115.

Were there not a modern county hospital located nearby, Supply would be little more than a crossroads village scattered along U.S. 17 on the southern fringes of the Green Swamp. Indeed, its sleepy appearance belies its historic past. From 1805 to 1810, Supply was the county seat of Brunswick County, and a courthouse stood in the village.

After 5.4 miles on S.R. 1115, turn south onto S.R. 1231 and proceed 0.5 mile to the community of Stanbury. At Stanbury, turn east onto S.R. 1122 for a 1.5-mile drive to Varnum.

This village of fewer than three hundred inhabitants is one of those out-of-the-way places that give the North Carolina coast its charm. It is at coastal communities like Varnum, which are not shown in guidebooks or glossy chamber-of-commerce brochures, that the character of the coast can best be appreciated.

Located on the banks of the Lockwoods Folly River, this fishing community is also known as Varnam, Varnumtown, and Varnamtown. Locals tend to prefer the latter two names, although the state spells it Varnum on county maps.

Whatever the spelling, the settlement traces its origin to Roland Varnum, who migrated from Maine to the Lockwoods Folly area in the early eighteenth century. Many of the current residents are Varnams or Varnums. Even though their brotherly disagreement over the spelling of their last name continues, they are all descendants of the original Varnum family.

On the docks of the picturesque hamlet, visitors can purchase fresh seafood as it is unloaded from the boats and chat with fishermen whose families have known no other way of living. During the winter months, the local shrimpers fish the Florida Keys, but by springtime, they return to the Brunswick coast to trawl the local waters.

Of special interest dockside is the marine railway used for pulling the large fishing vessels from the water for cleaning. This facility is one of the few marine railways in Brunswick County, one of the biggest commercial seafood producers in North Carolina.

Begin retracing S.R. 1222 from Varnum. Turn west onto S.R. 1120 halfway to Stanbury. After 2 miles, S.R. 1120 intersects N.C. 130. Turn south on N.C. 130. It is 1 mile to Holden Beach, the second-largest island on this tour.

A twisting high-rise bridge, completed by the state in 1986 to replace an antiquated drawbridge that caused massive traffic jams in the summer, affords a spectacular view of the island and the numerous shrimp boats that make it their home port. Eleven miles in length, Holden Beach is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean on the south, Lockwoods Folly Inlet on the east, Shallotte Inlet on the west, and the Intracoastal Waterway on the north.

Once on the island, turn east onto Ocean Boulevard, the oceanfront road that runs the length of Holden Beach. The island’s eastern end—from which Long Beach can be seen across the inlet—is less than 1.5 miles distant. It is from the beach near the end of the road that beachcombers make their way to the exposed Civil War shipwrecks in the inlet.

Retrace your route west on Ocean Boulevard and drive to the guard house for the private development on the western end of the island.

Along the way, it will become evident that the island has been developed almost to the saturation point. More than seventeen hundred vacation cottages not only crowd the oceanfront, but also the leeward side of the island, where numerous concrete finger canals have been built to provide access to the Intracoastal Waterway. Though the island has a permanent population of less than seven hundred, upwards of ten thousand sun worshippers and fishermen crowd its landscape during the summer months.

It has not always been this way. When Hurricane Hazel tore into the island with winds in excess of 150 miles per hour, just twelve of its three hundred cottages remained on their foundations. The hurricane made landfall at the worst possible time: high tide during a full moon. The storm surge created a gaping inlet that severed the island. Federal funds were used to fill the inlet nearly a year later.

References to “Holden’s Beach” date back as far as 1785. The island was named in honor of Benjamin Holden, who received a land grant from the king of England that included the island and much of the mainland as far back as the present U.S. 17. Thereafter, the island was handed down through the Holden family from generation to generation. Today, the Holdens continue to maintain significant property interests on the island.

Resort development at Holden Beach began in 1925, when a creek separating the island from the mainland was bridged. A year later, the first hotel, a ten-room structure on pilings, was erected by John Holden, Jr. The Great Depression hampered further development. As the 1930s drew to a close, the island boasted fifteen cottages and a pavilion. The modern resort emerged from the devastation of Hurricane Hazel.

Much like Oak Island, its sister island to the east, Holden Beach is recognized as a family-oriented vacation spot. John F. Holden proudly proclaimed in 1988 that Holden Beach “is the only incorporated town in Brunswick County that does not have an ABC store, liquor by the drink, beer sales, or night clubs.”

The western end of the island overlooks Shallotte Inlet, which separates Holden Beach from Ocean Isle Beach. Thousands of vessels of all sizes and shapes ply the mouth of the Shallotte River on their travels along the Intracoastal Waterway. Little do most of the mariners realize that the waters of the inlet are reputed to have curative powers.

For many years, reports have flowed out of the area that people who bathe in the inlet near a place called Windy Point are mysteriously cured of infections. Such tales have brought visitors from as far away as Canada to avail themselves of the waters and take supplies of it home.

The most plausible explanation for the curative powers concerns a peculiar type of reed that grows in the inlet and nowhere else. Found in the center of the reed is a breadlike substance, on which a mold develops when the reed is inundated with salt water. As the mold is washed off, the water turns a milky color. It is in these milky waters that the miraculous cures have reportedly taken place.

Some who believe in the curative powers assert that these are the same healing waters of which Ponce de Leon wrote. Indians told him that healing waters were located to the north at the end of a journey of many moons’ duration, but the famed Spanish explorer—more interested in gold and the Fountain of Youth—apparently never searched for them.

Although the scientific community has expressed skepticism about the curative powers of the waters, a number of documented cases exist. Perhaps the best-known incident occurred in 1945, when Joseph Hufham, a newspaperman from nearby Whiteville, was fishing from a boat anchored in Shallotte Inlet. Hufham was suffering from an eye disease which was gradually worsening despite constant medical care, special glasses, and medication. At times, his pain was so excruciating that he even rubbed alcohol into his eyes to obtain temporary relief.

On this occasion, the sun’s reflection on the waters of the inlet hurt his eyes to the point that he could not keep them open long enough to bait his hook. To soothe the pain, Hufham decided to go for a swim. As soon as he resurfaced from his dive, the pain was gone, and it never recurred.

For several years thereafter, Hufham collected and published reports of the unusual cures that had occurred at Shallotte Inlet. One involved an eighty-one-year old Indian who had lived in the area all of his life and had heard tales of the waters since his youth. Hufham witnessed the cure of a twelve-year-old boy whose grotesquely swollen arm was returned to normal after it was dipped in the waters of the inlet.

He issued invitations to scientific and medical organizations to study the waters, but he was consistently turned down. In the 1950s, when the American Medical Association warned him that he would be prosecuted for practicing medicine without a license if he persisted in extolling the virtues of the waters, Hufham fell silent.

Nonetheless, the mystery persists. People continue to seek the healing powers of the waters. Science has yet to prove them wrong.

From the guard house, retrace your route to N.C. 130 and proceed over the bridge to the mainland. It is drive of 9 miles to Shallotte. Along this route, the local boat-building industry is very much in evidence. Local craftsmen, often working without blueprints, fabricate large, seaworthy fishing boats in their yards using methods that have been handed down for generations.

Until the late 1980s, when a multilane bypass was constructed around “downtown” Shallotte, the two lanes of U.S. 17 carried a heavy volume of traffic through the heart of the town of some fifteen hundred residents. Over the past forty years, a heavily developed 2-mile commercial strip has grown up along the old “Ocean Highway.”

Entering Shallotte, N.C. 130 merges with U.S. 17 Business and follows the old route through town. From the bridge, you will enjoy a spectacular view of the Shallotte River, which rises near the town and provides at least two feet of water here, with three more feet at high tide. As the river flows from Shallotte, it broadens significantly until it reaches the ocean at Shallotte Inlet.

A settlement named Shallotte has been located in Brunswick County for many years. According to the Pennsylvania Gazette of April 29, 1731, there was a Shelote as early as 1729, but the exact location of the place is unknown. The year 1840 saw an unsuccessful attempt to establish a village at the mouth of the river. Finally, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the community of Shallotte was settled at its present site. By 1899, when the town was incorporated, its population was 149.

It is believed that the town received its name from the wild onions, or shallots, that grow in local fields and on the banks of the river. For the past four decades, Shallotte has served as the commercial hub for the beach resorts on the nearby barrier islands.

At Shallotte, turn south onto N.C. 179 and proceed 6 miles to N.C. 904. Turn south on N.C. 904 and drive across the high-rise bridge that spans the Intracoastal Waterway to 7-mile-long Ocean Isle Beach. Just after crossing the bridge, turn left on Second Street and proceed 1 block east to the Ocean Isle Museum of Coastal Carolina.

In January 1988, a group of local property owners organized the Ocean Isle Museum Foundation. Three years of hard work and fund-raising culminated in the Ocean Isle Museum of Coastal Carolina, which opened in the spring of 1991 in a handsome 7,500-square-foot building. Designed to make a significant contribution to the coastal Carolinas as both an educational and cultural facility, the museum offers a wide variety of interesting exhibits, including historic artifacts, native shells, mounted wildlife of the local marshes and swamps, and displays of wave and tidal action.

Return to N.C. 904. Turn south on N.C. 904 and drive 1 block to First Street, the oceanfront boulevard. Turn left, or east, onto First and proceed 3 miles to the eastern end of the island for a tour of the local landscape.

Ocean Isle Beach is considered the most upscale of the Brunswick Islands. Virtually all the land here that is suitable for development has been sold. Some lots have been sold on land that is nothing more than filled-in marsh.

The development of the island began in 1950 as a dream of Odell Williamson, who subdivided the sparsely inhabited island into lots and began constructing concrete finger canals, now prevalent on the eastern half of the island.

Few places on the North Carolina coast suffered the wrath of Hurricane Hazel more than Ocean Isle. The storm completely destroyed thirty-three of the thirty-five structures on the island, and the two buildings that survived were found more than a mile from their original sites. Ocean Isle also sustained the highest loss of life of any place in the Carolinas. When Hazel moved northward, the grim totals at Ocean Isle were eleven dead and seven missing.

Turn around and follow First Street for 5 miles toward the other end of the island.

Particularly noticeable on the western end are two fifteen-story condominiums, the first such structures in Brunswick County. They stand incongruously on the island landscape, perhaps foreshadowing an invasion of development from the nearby South Carolina Grand Strand. The public road ends in the shadow of the tall structures.

When you are ready to leave Ocean Isle Beach, retrace your route to N.C. 904 and head back across the Intracoastal Waterway. At the intersection of N.C. 904 and N.C. 179, turn west onto N.C. 179. Less than 0.5 mile from the intersection, turn left onto S.R. 1159. Here lies a majestic place where the simple beauty of the North Carolina coast can be enjoyed in its pristine state.

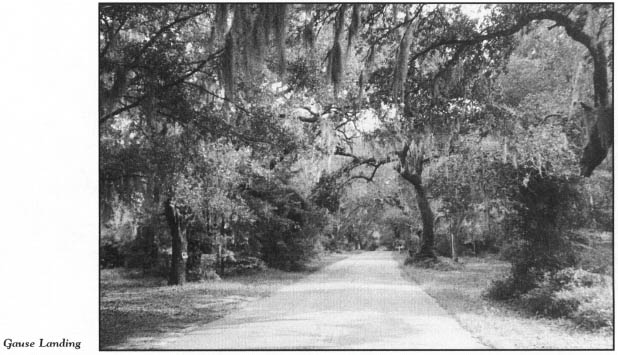

Set amid a backdrop of live oaks festooned with Spanish moss, Gause Landing is a tranquil fishing village just across the waterway from Ocean Isle. Its quiet streets are shaded by trees equal in size and beauty to those at Orton Plantation and other showplaces of the Cape Fear region.

Visitors might be surprised to learn that in the distant past, this village was a thriving center of water commerce.

Upon their arrival in the North Carolina colony from Bermuda in the eighteenth century, the Gause family established temporary roots at Town Creek in northeastern Brunswick County. However, the prevalence of yellow fever there caused the Gauses to move 40 miles down the Brunswick coast, where they founded the community of Gause Landing. In his diary, President George Washington noted that he visited Gause Landing and stayed a night as the guest of the Gause family during his famous Southern tour.

Without question, the most famous local historic site is the Gause Family Cemetery, located on the grounds of the ancient plantation built by William Gause on a bluff overlooking the modern Intracoastal Waterway. Within the cemetery is a brick burial vault constructed in 1836 under the terms of the will of John Julius Gause. Several decades ago, after vandals had broken into the tomb, a family member had it resealed. Vandals struck again by removing an inscribed stone over the door of the tomb. After the second episode of desecration, the Gause descendants removed the remains of their ancestors and reinterred them at an undisclosed location.

Although it is not readily apparent, there are eight to ten graves surrounding the tomb. Since tombstones were not easily available in the area at the time these graves were filled, small cedar trees were planted to mark the graves. Some of the trees remain today.

From Gause Landing, return to N.C. 179 and continue west for 4.5 miles to Sunset Beach, the southernmost developed barrier island in the state. This 3-mile-long island has been termed the most beautiful in Brunswick County. Located just northeast of the South Carolina line, Sunset Beach is separated from Ocean Isle Beach, located to the east, by Tubbs Inlet. It is separated from uninhabited Bird Island, to the west, by Mad Inlet.

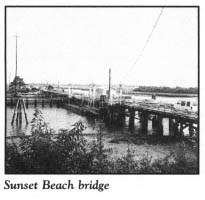

When Hurricane Hazel struck Brunswick County, property losses at Sunset Beach were less than at the nearby barrier islands, thanks to the island’s light development. In 1955, the year after Hazel, the entire island was purchased by Mannon Gore for sixty thousand dollars. During the next three years, Gore busied himself constructing roads and a bridge to the island. In 1961, the state took over responsibility for the maintenance of this unique pontoon bridge, which is the center of a great controversy today.

Within the next few years, this coastal landmark will be nothing more than a pleasant memory. It is slated to give way to a 65-foot high-rise span. Technically known as a “steel barge swing span,” the existing bridge is a single-lane, 13.5-foot-wide structure with a tender’s office in the middle. Unlike traditional drawbridges, which are raised or turned laterally on a support, the movable portion of the Sunset Beach bridge floats on a pontoon barge. The last of its kind not only in North Carolina but on the entire eastern seaboard, the bridge has been a significant part of the island’s charm since its initial development.

Turn east onto Main Street, the oceanfront road running the length of the island. You will notice that the Sunset Beach oceanfront features a wide zone of sand hills covered with beach grass and sea oats. The oceanfront structures here are set back much farther from the Atlantic than at any other beach on the North Carolina coast.

On the eastern end of the island, just south of Tubbs Inlet, the wreckage of the blockade runner Vesta, a five-hundred-ton, double-propeller vessel, is exposed at low tide. On January 10, 1864, the ship was en route to Wilmington from Bermuda when she ran aground while being chased by three Union ships. She was subsequently set afire by her crew.

Turn around and drive to the western end of the island. Bird Island, a small, undeveloped barrier beach which lies partly in South Carolina, is visible across Mad Inlet. The island can be reached only by boat or by wading or swimming across the inlet from Sunset Beach at low tide. Visitors considering making the trip should pay close attention to the tide, because the inlet is too deep to cross when the tide comes in.

For many years, Bird Island has been a popular place for picnics and shelling. Less than 2 miles in length, and too small to support large-scale development, the 1,150-acre island may nevertheless soon be overrun by bulldozers. In 1992, the longtime owner of the island began the application process to bridge the inlet and to develop 150 acres of land.

From the western end of Sunset Beach, return to N.C. 179. Proceed northwest on N.C. 179 for 4.2 miles to Calabash. At the traffic light on N.C. 179 in Calabash, turn south onto River Road, the road leading to the historic waterfront.

Few place names on the North Carolina coast are more nationally and internationally known than Calabash. For more than four decades, this tiny town nestled on the banks of the Calabash River has been a seafood lover’s paradise. No town its size anywhere can boast more seafood restaurants. Some 1,300 people call Calabash home. There is a seafood restaurant for every 75 or so of them. Strung along U.S. 179 and River Road, these restaurants serve seafood to more than 1.25 million patrons each year.

Not only has the abundance of restaurants put the town on the map, but so has the method of preparation of Calabash seafood, imitated all over the South and in other parts of the country. Restaurants that claim to cook their seafood “Calabash-style” are spread well beyond the boundaries of Calabash itself.

For most of the day, Calabash is a slow-paced, one-stoplight community. However, after four o’clock in the afternoon, automobiles bearing license plates from all over the United States and Canada begin pouring into town, bearing hungry diners to the place acknowledged by the food editor of the New York Times as “The Seafood Capital of the World.” By six o’clock, many of the waterfront restaurants have long lines of patrons.

The town had its beginnings in colonial days, when a settlement emerged on the riverbanks where planters brought their peanut crops for shipment. Over time, the village became known as Pea Landing. By 1873, when the name was changed to Calabash—a name taken from a variety of gourd, samples of which hung outside local wells—the community was a flourishing trade center.

Fifty years later, the town was fast becoming a ghost town. Had it not been for the seafood industry, Calabash might not have survived.

In 1935, a rustic wooden shed with a sawdust floor became the first seafood restaurant in the village. Five years later, Vester Beck opened an indoor restaurant. After learning Beck’s special preparation technique for shrimp, his sister-in-law, Lucy Coleman, opened her own restaurant nearby. Yet on a leisurely drive through modern Calabash, it is easy to become confused as to which of the restaurants was the original. Signs claiming that particular restaurants are the “Original” or the “First and Only” are visible throughout the town.

Before newspapers made Calabash a well-known place name throughout the country, one of America’s best-loved entertainers mentioned the town’s name at the close of his shows. Few Americans over the age of thirty will ever forget Jimmy Durante’s famous closing line: “Goodnight, Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are.”

There is little doubt that “the Old Schnozzola” was referring to the seafood town when he ended his shows. However, there are two theories about the person to whom he was speaking.

Durante dined often at Coleman’s Restaurant in the 1940s. There, he joked with Lucy Coleman and called her Mrs. Calabash. Thus, some locals contend that Durante was referring to the restaurant owner in his closing line.

Another explanation concerns a woman who once performed with Durante. This woman moved to Calabash to live near her father, who had a small house near the South Carolina border. Atop the house was an antenna, and the woman’s father was implicated in a scheme to send messages to German ships off the North Carolina coast. Jimmy Durante begged this “Mrs. Calabash” to resume her work with him, but she refused, insisting on remaining with her father. Both she and her father later disappeared.

From the Calabash waterfront, return to N.C. 179 and proceed west. It is 0.4 mile to S.R. 1168 (Country Club Road). Turn north on S.R. 1168.

Nearby is a six-hundred-pound granite post erected by surveyors in 1928 to mark the former site of Boundary House. Standing astride the state line, this house was an important landmark in the boundary survey between the two Carolina provinces in 1735.

At one time, Boundary House was the home of Isaac Marion, brother of General Francis Marion, the famed “Swamp Fox.” On May 9, 1775, the people of South Carolina learned of the Battle of Lexington when an express horseman from Wilmington delivered the message to Boundary House.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, only the chimney of the house was standing.

When the line between the two states was last surveyed in 1928, the exact location of the house had to be determined in order to achieve an accurate survey.

Continue 1.2 miles on S.R. 1168 to the intersection with U.S. 17, where the state of North Carolina has erected a historical marker for Boundary House. The tour ends here, 0.9 mile from the South Carolina line.