This tour begins at the intersection of N.C. 130 and U.S. 17 on the outskirts of Shallotte. Proceed northwest on N.C. 130 as it twists its way into and through the Green Swamp, a 140-square-mile wilderness of pocosins, wetlands, and pine savannas.

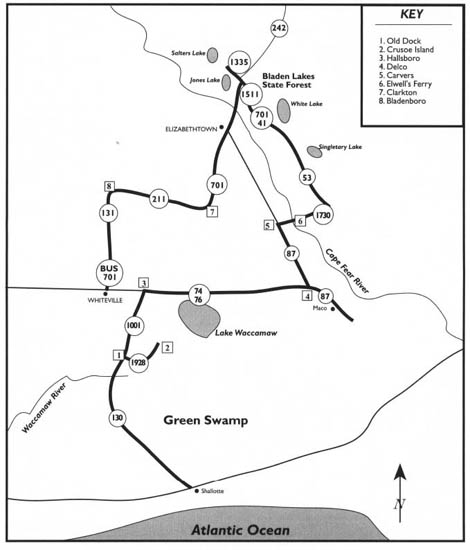

This tour begins with a drive through the Green Swamp and visits to Old Dock and mysterious Crusoe Island. It then travels to Lake Waccamaw, Maco, Bladen Lakes State Forest, Singletary Lake State Park, White Lake, Jones Lake State Park, Elizabethtown, Clarkton, and Bladenboro before ending near Whiteville.

Among the highlights of the tour are some of the most famous of the Carolina bay lakes, the story of headless Joe Baldwin, the story of Battle Royal, the two-vehicle Cape Fear River Ferry, the story of Anna McNeill Whistler, the story of the Beast of Bladenboro, and the story of Mille-Christine McCoy, the world-famous Siamese twins.

Total mileage: approximately 175 miles.

Although farming and timber production have greatly reduced the size of the Green Swamp over the past two hundred years, it still covers an enormous 20-mile swath of land in Brunswick and Columbus counties between U.S. 17 and U.S. 74. Within this forbidding jungle—portions of which have never been seen by the eyes of man—are stands of ancient cypress, impenetrable thickets of vines, and meandering creeks and streams.

Named for John Green, the man to whom the expanse was granted by the Crown, the swamp was considered worthless until the twentieth century.

Patrick Henry of Virginia once owned land here. Today, most of the swamp is owned by Federal Paper Board Company of Montvale, New Jersey. In 1977, three years after the swamp was declared a national natural landmark by the Department of the Interior, Federal Paper Board donated 13,850 acres to the North Carolina Nature Conservancy for the establishment of the Green Swamp Preserve. Subsequent acquisitions by the Nature Conservancy have increased the size of the preserve, making it one of the largest and most significant wetland areas in the state.

Much of the preserve is open to the public, but venturing into the swamp without an experienced guide is ill-advised. Numerous dangers—such as quicksand, peat holes, dense undergrowth, poisonous snakes, alligators, black bears, and bobcats—have swallowed up unwary explorers in the past.

Thirteen miles from Shallotte, N.C. 130 crosses the black, snakelike Waccamaw River. Park near the bridge for a panoramic view of the river and the surrounding swamp.

Considered one of the most picturesque and unspoiled waterways in coastal North Carolina, the Waccamaw River rises at Lake Waccamaw and flows into South Carolina, where it empties into the Atlantic. At many places within the Green Swamp, the course of the river is indistinguishable from the adjoining swamp.

The river is named for the earliest known inhabitants of its banks, the Waccamaw Indians. Although the Waccamaws aided Carolina colonists in their reprisals against the Tuscaroras in 1712, the tribe was gradually decimated throughout the eighteenth century by hostile encounters with white explorers and settlers and exposure to new diseases. Ultimately, the surviving members of the tribe fled to join the Catawbas in the western Carolinas and the Seminoles in Florida.

Permanent white settlement along the river took place in the mid-eighteenth century. Over the next hundred years, immense quantities of naval stores were brought forth from the dense swamp forests bordering the banks. Vast stands of cypress trees led to the development of a significant cypress-shingle industry in the nineteenth century.

Approximately 6 miles past the bridge over the Waccamaw River, you will reach the tiny village of Old Dock, once a key port on the river for the shipment of cypress shingles and lumber. When Old Dock was settled in 1800, and during the entire nineteenth century, the river was much wider and deeper than it is now, making it navigable for deep-draft vessels. As late as 1895, a steamer ascended the river from Georgetown, South Carolina, to Lake Waccamaw, some 8 miles north of Old Dock.

During its long-forgotten heyday, Old Dock, originally known as Pleasant View, was a bustling place, with turpentine distilleries turning out thousands of barrels of product for waiting barges and rafts, which were poled down the river by crews of up to fifteen men.

In the first quarter of the twentieth century, Old Dock was relegated to its present status as a crossroads community when the construction of a dam ended the Waccamaw’s days as a navigable river.

At Old Dock, turn right off N.C. 130 onto S.R. 1928 and head deeper into the swamp for a visit to one of the most mysterious communities of coastal North Carolina: River View. It is 2.7 miles to the intersection with S.R. 1930. Turn left and drive 2.3 miles along River View’s “Main Street.”

A quick glance at the homes and gardens in this isolated community gives the impression that it is no different from the hundreds of other rural settlements throughout coastal North Carolina. However, Crusoe Island, as River View was officially known until 1961, is an ancient place. It was home to white people long before other white settlers took up residence along the banks of the nearby river.

Why and how people of European descent came to settle deep inside one of the most remote and impenetrable swamps in the United States is one of America’s most enduring mysteries. Over the years, a wide variety of theories have been proposed. Some historians contend that the colony in this snake-and-alligator-infested wilderness was established by pirates who fled into the swamp after an unsuccessful raid on the nearby river. Others claim that the first residents were Indians and Europeans who intermarried and mixed. Still others believe that the original Crusoe Islanders were coastal residents who fled inland after being attacked by pirates. Crusoe Island has also been posited as the ultimate destination of the Lost Colonists of Roanoke Island.

Perhaps the most logical and satisfying explanation involves a group of French refugees who fled their mother country during the French Revolution. Among the refugees was a young French army surgeon, Jean FormyDuval. After being put ashore near Cape Fear, FormyDuval led his group into the Green Swamp in order to avoid being discovered by the authorities. In the heart of this jungle, the French settlers built a secret enclave so remote that few outsiders knew of its existence.

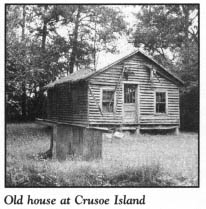

Though that theory has never been proved, and though some current residents of the swamp community doubt its validity, there are facts that lend credence to it. Traces of French heritage were discernible in natives of the village well into the twentieth century. Speech patterns, intonations, and conversational gestures of longtime residents hinted of a French background. Likewise, there is architectural evidence to support the theory. Chimneys that once stood at Crusoe Island were constructed of mud and sticks and covered with smooth white clay from the swamp. Old photographs reveal that the chimneys resembled those of cottages in Normandy.

Early national census records reveal other evidence. They disclose that a Dr. FormyDuval settled in the area just south of Lake Waccamaw between 1790 and 1800. Indeed, as you drive past the homes lining the road, you will notice last names on mailboxes—such as FormyDuval, Clewis, and Sasser—hinting of a French background. The last two names appear to be Anglicized versions of Cluveries and De Saucierre.

Local residents who discount the French-refugee theory contend that their ancestors were early English settlers of southeastern North Carolina.

Regardless of their origin, many of the first Crusoe Islanders obtained land grants from the state in the first half of the nineteenth century.

For more than a century, Crusoe Island was virtually hidden from the eyes of the outside world. Few residents emerged from their jungle settlement. Rather, the hardy settlers and their descendants developed a self-sufficient lifestyle. Men hunted and fished the swamp. Bountiful vegetable crops were produced from the dark, fertile soil. Home-grown cotton yielded thread, and hand-made looms produced cloth.

Likewise, only on rare occasions did outsiders make their way into the secluded colony before the twentieth century. In fact, Crusoe Island was not “discovered” until large timber companies sent engineering crews and loggers into the Green Swamp. From their initial contact with the Crusoe Islanders, the timber workers emerged to tell the world of an unusual people with a dialect totally unlike that spoken anywhere else.

It was not until the first bridges and roads to Crusoe Island were completed in the 1920s that the village was made accessible to the public. Prior to that time, the swamp residents forded the rivers and creeks on rare trips to Old Dock and other nearby towns.

Even though improved access to the outside world afforded children in the swamp an opportunity to attend public school at Old Dock and Whiteville, village residents were reluctant to give up their traditional ways of doing things. Outsiders who made their way to the community were shocked to find oxcarts rumbling down the unpaved roads. Reports of harsh treatment of visitors and strange occurrences in the village added to its mystery.

In the late 1950s, the state paved the road to Crusoe Island, but the community remained an isolated outpost in the jungle.

Crusoe Islanders successfully petitioned the state legislature to change the name of their community following an unflattering wire-service story that termed local residents “ignorant.” Despite the change, the village is still best known by its original name.

No one knows how this village of approximately five hundred residents came to be known as Crusoe Island. Most likely, it was named for Ben Crusoe, an early settler in the area. However, there are some who maintain that it was named for Daniel Defoe’s fictional adventurer, Robinson Crusoe.

After surviving more than seventy-five years of incursions by outsiders in this century, Crusoe Island remains a homogeneous community. Yet time and outside influences have taken their toll on the unique speech of the villagers. Even for residents who were born and have lived in the swamp all of their lives, the pattern of speech is not as pronounced as it once was. Nonetheless, some old-timers maintain the ancient drawl, which elongates the pronunciation of short words. Described as pleasant to the ear, this singsong speech is almost impossible to imitate.

Surrounded by the jungle that protected its privacy for centuries, the village rests on one of the largest “islands” of high ground in the Green Swamp.

The drive along S.R. 1930 dead-ends at the fringe of the swamp wilderness. Just beyond the terminus of the road is the wild splendor of the Waccamaw River.

Retrace your route to Old Dock. Turn right on N.C. 130 and proceed 1.8 miles to its intersection with S.R. 1001. Turn right onto S.R. 1001 for a scenic drive along the northwestern edge of the Green Swamp. Bridges cross many of the lazy creeks that twist through the pristine wilderness.

After 10 miles on S.R. 1001, you will reach the small village of Hallsboro. Turn right onto U.S. 74/76 for a 4.5-mile drive to Lake Waccamaw.

When viewed from the air, this portion of coastal North Carolina reveals a spectacular pattern of elliptical depressions spread over the landscape. Deriving their name from the area of their greatest concentration and from the place where they were first studied, the “Carolina bays” number more than half a million lakes along the Atlantic seaboard from New Jersey to Florida.

John Lawson, the early explorer of much of coastal North Carolina, first wrote about these peat-filled swamps, which range in size from four acres to thousands of acres.

Scientists have long debated the origin of the Carolina bays. The most plausible theory was espoused by Dr. W. F. Prouty, the former head of the Department of Geology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who postulated that a large meteorite shower smashed into the coastal plain during the late Pleistocene era.

Most scientists theorize that all of the bays were once filled with water. Many are now only peat-filled bogs. The tour route passes the greatest concentration of bay lakes in the world.

At the town of Lake Waccamaw, turn right off U.S. 74 onto N.C. 214, which stretches 2.5 miles along the northern shore of one of the most beautiful bodies of water in the world.

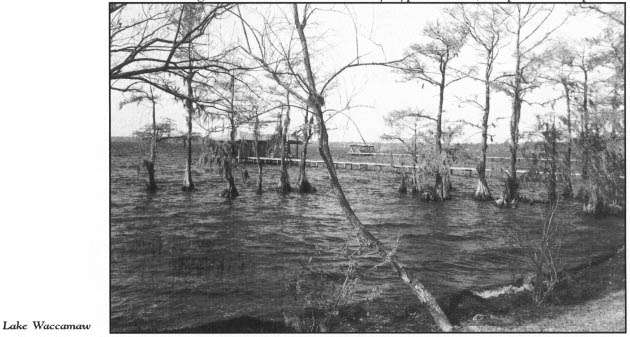

Measuring 5 miles long and 3 miles wide, and covering 8,938 acres, Lake Waccamaw is one of the largest natural lakes in North Carolina. It is little wonder that John Bartram, the famed Philadelphia botanist, fell in love with it during a visit in 1734. Its stately cypress trees, draped with Spanish moss and mirrored by shimmering waters, led Bartram to call the lake “the pleasantist place I ever seen in my life.”

There is no conclusive proof of the origin of the lake, although many geologists believe it to be a Carolina bay. If so, Lake Waccamaw is one of the largest bay lakes in existence. It differs from other local bay lakes in that it is not sterile. A limestone outcrop on the northern shore reduces the acidity of the adjacent swamp, and the lake therefore teems with fish and plant life.

John Powell, who moved here from Virginia around 1745, is thought to have been the first white settler on the lake. According to some historians, Osceola, the famous half-breed chief of the Florida Seminoles, was born on the southern shore of the lake. Tradition says that Powell was his father. The young Indian moved to Georgia as a child when the federal government removed the local Indians.

In 1852, Josiah Maultsby began development of the northeastern shore of the lake. By 1869, a small village known as Flemington had taken root, but it was not until the arrival of the railroad at the turn of the century that the lake became a summer tourist attraction. Pavilions and bathhouses sprang up along the northern shore to serve the large numbers of visitors who made their way here by train.

N.C. 214, which becomes Lake Shore Road, passes the lakeshore residential development that began after World War II. Paralleling the road is a portion of the 5-mile-long canal constructed in 1952. Though the dark waterway has a serene appearance, it is not unusual to spot an alligator basking in the sun nearby.

Follow the northern shore for an additional 3 miles by turning right off N.C. 214 onto S.R. 1947. Development on Lake Waccamaw, primarily in the form of permanent homes and summer cottages, has been limited to the northern and western shores.

Lake Waccamaw State Park, located just off S.R. 1947, remains one of the least-developed parks in the state system. Established in 1976, the park now includes the entire lake and 1,509 acres of land, primarily on the wild southern shore. As late as the 1950s, bear hunters killed as many as fifteen bears on regular hunts on the southern side of the lake, portions of which have never been fully explored.

The centerpiece of the park, the majestic lake, is an exquisite work of nature. A scenic park road extends almost a mile from the entrance to a parking lot. From there, a trail leads to the lake.

With an average depth of seven feet and a maximum depth of eleven feet, Lake Waccamaw is not very deep. Its water has a rich, dark hue but is remarkably clear. A person of average height can see the bottom of the lake when the water is up to his or her shoulders.

From the park, retrace your route to the junction with N.C. 214. If you are interested in taking a brief side trip to the southwestern shore of the lake, where the dam on the Waccamaw River is located, proceed west on N.C. 214, then follow S.R. 1900 and S.R. 1967 for approximately 5 miles.

Otherwise, turn right, or north, onto N.C. 214 for a 1.3-mile drive back to U.S. 74/76. Turn east on U.S. 74/76 for a 15-mile drive through the small communities of Bolton, Freeman, and Delco. Each of these settlements grew up alongside the railroad in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Although the ancient railroad running to Wilmington was abandoned and the rails removed more than fifteen years ago, the bed still runs parallel to the highway in the fringes of the swamp.

From Delco, U.S. 74/76 runs conjunctively with N.C. 87 for 5 miles to Maco, the home of the most famous ghost of coastal North Carolina. At Maco, follow N.C. 87 to the right when it splits off U.S. 74/76. Park near the old railroad bed after approximately 0.3 mile.

Although the railroad crossing has been paved over, the old railroad bed is visible nearby. If you visit on a warm, dark night, there is a possibility that you will encounter the spirit of Joe Baldwin, or so the legend goes.

About midnight on a rainy spring night in 1867, Joe Baldwin was working as the conductor on a freight train bound for Wilmington. Near the station at Maco, then known as Farmers Turnout, the rear car—the one in which Joe was riding—became separated from the rest of the train. Hoping to avert a disaster, Joe raced to the rear platform and waved his lantern from side to side to warn a fast-approaching train.

Despite the frantic warning, a terrible collision ensued, and Joe Baldwin was decapitated. His lantern was thrown into a nearby swamp by the force of the impact, but it continued to burn brightly. Authorities never found Joe’s head, and his body was buried without it.

Not long after the crash, local people began to notice an unusual light on the railroad tracks in the vicinity of the disaster. Appearing at fifteen-minute intervals, the light would make its way down the tracks, growing brighter and swinging up and down, until it came within seventy-five feet of the witnesses. Suddenly, it would take on a bright glow and speed away into the night. Eyewitnesses said it looked like someone was using a lantern to search for something on the ground. No other explanation being available, area residents concluded that the apparition was Joe Baldwin looking for his head.

Reports of the ghost spread far and wide. Soon, the curious were attracted to the site, especially on dark nights. Six years after the tragedy, railroad employees added credibility to the ghost story when they reported seeing the eerie light.

President Grover Cleveland was on board a train as it rumbled into the depot at Maco on a warm, muggy night in 1889. While the train was stopped, the president took a stroll to stretch his legs and to say a few words to the assembled crowd. During his brief layover in the tiny Brunswick County community, Cleveland was bewildered by a signalman holding red and green lanterns. Once the train got under way again, railroad employees related the Joe Baldwin story and explained that the dual lanterns were used to prevent confusion with the ghost light. According to some accounts, the president actually saw the light on his visit.

Over the years that followed, many trustworthy railroad men filed reports that they had seen the mysterious light. On many occasions, cautious engineers, confused by the light, brought their trains to an abrupt, unscheduled stop to avoid what they thought was going to be a collision.

Scientists have studied the phenomenon throughout the twentieth century, but no one has been able to conclusively explain the origin of the light. Foxfire, swamp gas, St. Elmo’s fire, and automobile headlights have been cited as causes. Adherents of the ghost story are quick to point out that the light is seen only on the railroad and not in the nearby swamp. Moreover, the light was observed long before the advent of automobiles.

On one occasion, a machine-gun company from Fort Bragg camped near the scene to solve the mystery. Attempts to shoot the light were unsuccessful.

Though the tracks on which the horrible accident occurred are now gone, visitors still peer up and down the empty railroad bed in hopes of seeing the phantom light that has mystified people for more than 125 years. Until a better explanation comes along, the notion that Joe Baldwin continues to search for his head is as plausible as ever.

Maco is located on the northeastern edge of the Green Swamp. Much like the community of Crusoe Island in the western portion of the swamp, an isolated, mysterious settlement existed near Maco until the first decade of the twentieth century. Known to its residents as Battle Rial or Batterial, Battle Royal was isolated from the outside world. Outsiders who braved the jungle to visit the place found “Over Creek People” whose ancestors had lived there since pre-Revolutionary War times. These people spoke Elizabethan English until the community was assimilated into the modern world in the first quarter of the twentieth century, when a public road was opened to the nearby community of Malmo.

One aged native of Battle Royal reported that his family had passed down the tradition that their ancestors “were Roe Noakers, from an island in the sea.” Perhaps this long-vanished settlement in the swamp held the answer to the mystery of the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island.

From Maco, retrace your route to Delco. When N.C. 87 splits back off U.S. 74/76 in Delco, turn right on N.C. 87, which parallels the Cape Fear River on its run to Fayetteville. It is 14 miles from Delco to Carvers, a small Bladen County community on the western side of the Cape Fear.

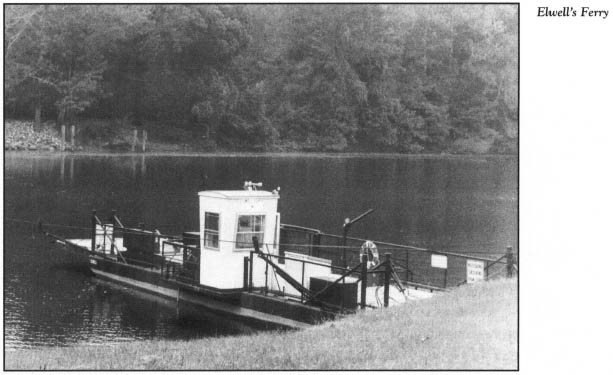

For a unique river crossing, turn right off N.C. 87 onto S.R. 1730. The road ends at the riverbank 3 miles to the east. No bridge crosses this isolated stretch of the river. Rather, the state operates the tiny, two-vehicle Cape Fear River Ferry, known locally as Elwell’s Ferry.

For almost ninety years, a small ferry has transported vehicles and passengers across the river at this spot. Though small and quaint when compared with the ferries that ply the North Carolina sounds, the river ferry is a modern bargelike vessel pulled along a cable by a diesel engine. Nearly seventy-five vehicles squeeze onto this free ferry every day. As one of only two river ferries in the state, the Cape Fear River Ferry is a remnant of a romantic bygone era of coastal history.

The upper stretch of the Cape Fear River in Bladen County was the site of many plantations that predated the Revolutionary War or the Civil War. Most of the plantation homes that overlooked the river from the high bluffs disappeared long ago. For example, all that remains of Owen Hill is an ancient burying ground which contains the unmarked grave of a servant, Omar Ibm Said, who penned his autobiography in Arabic in 1831.

After you cross the river, continue 1 mile on S.R. 1730 to its intersection with N.C. 53. Turn left onto N.C. 53 for a pleasant drive through rural Bladen County. It is 8.5 miles to the southern limits of Bladen Lakes State Forest. Named for the large, picturesque bay lakes within its boundaries, the 40,000-acre wilderness preserve is the result of one of the most comprehensive land-reclamation projects in American history.

Following the Great Depression, the forest was comprised of little more than pocosins and worn-out farmland. The federal government set about reclaiming the wasteland by relocating its owners and using the Civilian Conservation Corps to plant trees. In 1939, the land was turned over to the state and became a state forest.

Over the past half-century, this has evolved into one of the finest state-managed forests in the nation. It not only preserves rare ecological communities and offers outstanding recreational opportunities on the bay lakes, but also provides income for the state from pulpwood sales. Of even greater significance, the forest is an outstanding outdoor teaching laboratory. More than two dozen scientific research projects are being conducted within the forest at any given time.

Bladen County is the fourth-largest of North Carolina’s hundred counties. Within its massive boundaries are in excess of twelve hundred Carolina bays—more than in any other county in the nation. Singletary, White, Jones, and Salters lakes are large bay lakes within the state forest.

Continue 2.7 miles on N.C. 53 to Singletary Lake, the featured attraction of the state park of the same name.

Park roads circle most of the 572-acre lake, named for Richard Singletary, an early pioneer in the county. Hiking, swimming, fishing, boating, and camping are popular activities here and at the nearby state parks at Lake Waccamaw and Jones Lake.

Singletary Lake State Park features extensive camping facilities, including a group camp with an infirmary and dining facilities for a hundred campers, built by the federal government as a recreational demonstration project. Campers and day visitors alike are enchanted by the picturesque lake, which is framed by huge pond cypress trees and surrounded by rare plant communities which include insectivorous sundews and Venus’ flytraps. Reaching a maximum depth of twelve feet, Singletary is the deepest of the Bladen lakes.

From Singletary Lake, proceed north along N.C. 53 for 3 miles to White Lake. Turn right onto U.S. 701/N.C. 41, then right onto S.R. 1515 for a circular drive around the 1,068-acre lake.

Like the other bay lakes of five hundred acres or more in Bladen County, White Lake is owned by the state. However, in sharp contrast to the other lakes, the shore of White Lake is privately owned and has been subjected to resort development.

Without question, the most distinguishing feature of the majestic lake is its beautiful, clean water, enhanced by the white, sandy bottom. Although its average depth of 7.5 feet makes White Lake one of the deepest of the Bladen lakes, the water is so clear that the bottom can be seen even where the depth reaches 10 feet near the southeastern corner.

White Lake has no inlets or outlets, other than drainage ditches that maintain the water at sixty-six feet above sea level. Instead, it is fed by rainwater and artesian wells, some of which are visible to boaters. As a result, it never loses its clarity.

Scientists as well as visitors have long been fascinated by the crystal-clear water. Chemists have found it to be purer than that produced by municipal water systems.

Botanist William Bartram studied and wrote about White Lake in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Originally known as Granston Lake, the lake was subsequently renamed Bartram’s Lake for either the botanist or his uncle, a resident of the Cape Fear region. Since 1886, it has been known by its present name.

Despite White Lake’s recreational potential, the public did not begin to use the lake as a resort until 1907, when Ralph Melvin opened a public beach. A hotel, cottages, and a bathhouse were added in subsequent years as Melvin Beach grew in popularity. Roads were constructed in the early 1920s to link the lake with other parts of the state, thereby throwing the door open to widespread development. Within ten years, more than a half-dozen public beaches—including Goldston’s Beach and Crystal Beach, which are still in operation—were attracting vacationers from North Carolina and adjoining states.

Over the past half-century, the 4.5-mile lakeshore has been almost completely developed, with motels, campgrounds, summer homes, and various amusements. A number of public beaches offer bathhouses for visitors who want to enjoy the gentle beaches and special lake water, the carnival rides and arcades, the gift shops, and the refreshment stands.

While the resort has taken on a more pronounced local flavor in the past decade, the beaches and parking lots remain crowded with visitors from all over the state at the peak of the summer season.

After circling White Lake, you will reach the junction of N.C. 53 and U.S. 701/N.C. 41. Turn left onto U.S. 701/N.C. 41, drive 1.6 miles, and turn right onto S.R. 1511 for a 5.2-mile drive through the Bladen countryside to Jones Lake, located at the junction of S.R. 1511 and N.C. 242.

Named for Isaac Jones, the man who provided the land upon which the nearby town of Elizabethtown was built, Jones Lake is the smaller of the two bay lakes located within 2,208-acre Jones Lake State Park. Visitor facilities and the park’s headquarters are located at Jones Lake, a beautiful, tree-lined, 224-acre lake whose sandy beaches and calm waters are popular with swimmers. Extensive hiking trails around the lake offer an excellent opportunity to view the flora and fauna of the Carolina bay environment.

After visiting Jones Lake, turn left, or north, onto N.C. 242. After 1.5 miles, turn left onto unpaved S.R. 1335. Salters Lake, the larger of the two lakes in the state park, lies just south of the road after approximately 1.2 miles on S.R. 1335. This 315-acre lake, managed as a natural area, is an outstanding example of a water-filled Carolina bay. A small boat landing and a parking lot are located here, but visitors must obtain advance permission from park personnel for access to the lake.

Return to N.C. 242, turn right, or south, and proceed 4.5 miles to the junction with U.S. 701. Drive south on U.S. 701 for 1 mile to the bridge over the Cape Fear River. On the southern side of the bridge, turn right at the entrance to Tory Hole Park. This waterfront park offers picnic facilities, hiking trails, and a boat landing in a beautiful, forested setting along the river. It is named for the deep gully into which fleeing Tories leaped after a Revolutionary War battle at nearby Elizabethtown in August 1781.

From the park, proceed south on U.S. 701 for 0.2 mile to Elizabethtown, the county seat of Bladen County. Located on a 125-foot bluff above the Cape Fear River, the town was created by the colonial assembly in 1773. It was named either for the girlfriend of Isaac Jones, the man on whose land the town was established, or for Queen Elizabeth I. Today, Elizabethtown is a bustling place—the largest town in Bladen County.

In the heart of town, at the intersection of U.S. 701 and N.C. 87/41, stands the Bladen County Courthouse. Completed in 1965, this large, multistory brick building is the fourth courthouse to stand in Elizabethtown.

A monument on the courthouse grounds honors Mrs. Sallie Salters, who became the heroine of the Battle of Elizabethtown during the Revolutionary War when she hurried into town, innocently bearing an egg basket, to gain valuable intelligence about the location of the Tories. Salters Lake is named in honor of Sallie Salters and her husband, Walter.

Turn east off U.S. 701 onto N.C. 87/41 (Broad Street) and drive 3 blocks to Trinity Methodist Church, the most prominent of the historic buildings in the downtown area. This tall, frame church building, erected in 1836, towers over Broad Street at its intersection with South Lower Street.

From the church, retrace your route to the courthouse. Turn left onto U.S. 701 and follow it south from Elizabethtown on a 10.5-mile drive to the thriving agricultural town of Clarkton, on the southern border of Bladen County. Be sure to follow U.S. 701 Business when the highway divides 9.3 miles south of Elizabethtown.

Settled by Scotch Presbyterians almost 250 years ago, Clarkton was the home of the subject of one of the most recognizable paintings in the world. For a number of years prior to the Civil War, Anna McNeill Whistler, born in Wilmington in 1804, made her home at Oak Forest Plantation, just north of downtown Clarkton. The historical marker at the intersection of U.S. 701 Business and S.R. 1760 in Clarkton stands approximately 0.75 mile west of the plantation site.

At the outbreak of the war, Mrs. Whistler, by that time a widow, left North Carolina, fearing reprisals because her husband, a West Point engineer, had been an officer in the United States Army. She sailed out of the Cape Fear River on board a blockade runner, heading to Europe to join her first-born son, whom she addressed as Jamey.

Her son, an artist, persuaded his mother to pose for a painting, which he officially titled Arrangement in Gray and Black No. 1. When he completed the masterpiece in Paris in 1881, James McNeill Whistler sold it for $620. Now known the world over as Whistler’s Mother, it is the only painting by an American artist to hang in the Louvre in Paris.

Built in 1737, Mrs. Whistler’s plantation home in Bladen County was gutted by fire in 1933, some fifty years after her death.

Turn right off U.S. 701 onto N.C. 211 in Clarkton. It is 8 miles to Bladenboro, a textile town of fifteen hundred people.

Forty years ago, this community was in the national spotlight when reports came to light that a vicious, bloodsucking monster was loose in the swamps surrounding the town. The Beast of Bladenboro soon became a part of North Carolina folklore.

On the night of December 29, 1953, a young Clarkton housewife reported seeing a monster resembling a big cat in the darkness outside her house. A day later, Lloyd Clemmons of Bladenboro claimed the monster had dragged a dog into a nearby swamp. When the unfortunate animal was found, the blood had been drained from its body, though its flesh had not been devoured. Similar reports poured into the Bladenboro Police Department. The mayor telephoned the information to the Wilmington newspaper, which informed its readers in a front-page story that “a mystery killer beast with a vampire lust” was stalking the Bladenboro area.

Search parties organized by the Bladenboro police scoured the nearby swamps, but they produced only one piece of tangible evidence: large tracks the size of half-dollars, with one inch claws. Soon, reporters and curiosity seekers poured into Bladenboro. As interest in the story grew, so did wild rumors. Reports that a rabbit had been found with its head bitten off and that two beasts might be roaming the area sent panic through the townspeople.

To complicate matters, the mayor, who operated the local movie theater, rented a grade-B movie, The Big Cat, which played to a packed house. Things got completely out of hand when hordes of gun-toting, homemade-whiskey-drinking hunters and armed fraternity brothers from as far away as Raleigh took to the streets to find the beast.

When the police chief threatened to call in the National Guard to quell the widespread panic, the mayor ended the nightmare almost as quickly as it had begun. He prominently displayed a bobcat recently killed by a local hunter. Photographs of the dead “monster” were dispatched to the press.

To this day, no one knows what kind of creature the Beast of Bladenboro was. Some say it was a coyote or a feral dog, while others say it never existed at all. Some residents of Bladenboro claim that the cries of the beast can still be heard in the darkness of the swamps.

Turn left off N.C. 211 onto N.C. 131 in Bladenboro. It is approximately 9 miles to the intersection with U.S. 701 Business. Turn right onto U.S. 701 Business and drive 6 miles to Whiteville, the county seat of Columbus County.

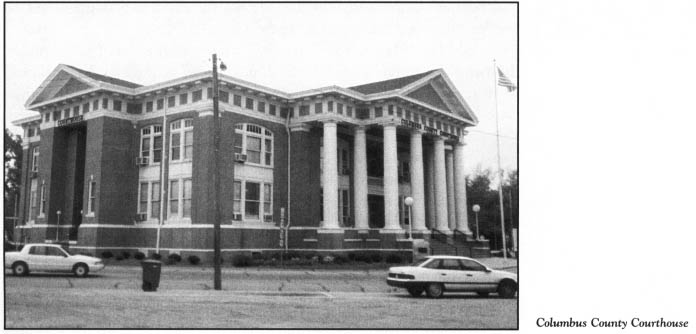

In Whiteville, U.S. 701 Business intersects U.S. 74/76 Business at the Columbus County Courthouse. Constructed in 1914 and 1915, this handsome, two-story, brick Neoclassical Revival building was designed by J. F. Leitner, a prominent architect who settled in Wilmington in 1895.

In 1810, two years after the formation of Columbus County, Whiteville was authorized to be laid out on land owned by James B. White, a local planter and politician.

Yet long before this bustling town in the heart of tobacco country was established, a true love story had its happy ending here. Duncan King, a privateer in the service of the Crown, made port at the mouth of the Cape Fear River in the fall of 1752. With him was a five-year-old girl he had rescued in the Caribbean after pirates attacked her ship and killed her French parents. King located some French-speaking residents and left little Lydia Fosque with them. Shortly thereafter, he sailed away.

While Lydia was growing into a beautiful young lady, King was serving with distinction in the British army in Canada.

In 1761, Lydia’s guardian decided that she and her ward should move to Savannah. As they waited for their ship near Fort Johnston, at modern-day Southport, Lydia’s long-vanished hero, Duncan King, walked down the gangplank. He was taken by her beauty. The two soon fell in love, and they were later married.

Duncan King used the wealth he had accumulated during his service to the Crown to purchase several thousand acres in Columbus County. There, he and Lydia lived in happiness until he died in 1793. From this Columbus County romance came many noteworthy King descendants, including Civil War heroes, the founder of Kings Business College, and a vice president of the United States, William Rufus King.

Turn east off U.S. 701 Business onto U.S. 74/76 Business in Whiteville. After 3.3 miles on U.S. 74/76 Business, turn left onto S.R. 1700. Drive 3.1 miles on S.R. 1700, then turn left onto S.R. 1719. It is 0.9 mile to Welches Creek Community Cemetery.

A granite grave monument here reads, “A soul with two hearts. Two hearts that beat as one.” Interred at this site are the remains of Mille-Christine McCoy, the world-famous Siamese-twin girls.

On July 11, 1851, on the Columbus County plantation of Jabe McCoy, the twins were born joined at the hip to slaves of African descent. Sold when they were one year old, they were exhibited in Europe, where physicians concluded they could not be separated because their spines were fused. Pearson Smith, a subsequent owner, successfully promoted them on a world tour. They were received by the royalty of many nations, including Queen Victoria, who presented them with gifts. She enjoyed their singing and requested return visits.

Following their liberation during the Civil War, the twins retained Pearson Smith as their manager. Their success continued when they performed for President Lincoln. Highly intelligent, they spoke five languages fluently. Through their world travels, Christine acquired a love of Shakespeare.

By 1892, the twins had tired of touring and retired to Columbus County. Back home, they were generous with the wealth they had acquired. Not only did they build homes for family members, but they also constructed a church and a school for black children in the county. Their generosity benefited a number of schools of higher learning, including Johnson C. Smith University, Shaw University, and Bennett College.

The twins requested that they be referred to as one. Often, they spoke in unison. They walked on two of their four legs.

When Mille died of tuberculosis on October 8, 1912, Christine told of her death before those in attendance could detect it. The surviving twin lingered another day, calmly singing hymns and praying.

From the cemetery, retrace your route to U.S. 74/76 Business, where the tour ends. A state historical marker honoring Mille-Christine stands nearby.