One

LIVING ON THE WATER

Water has always been the common denominator of life in Accomack County. Years ago, Native Americans gathered shellfish on tidal flats, caught sturgeon in weirs, and traded goods with other Indian nations using bays, rivers, and creeks as avenues of commerce.

Europeans arrived shortly after the Jamestown settlement of 1607, exploring the Eastern Shore peninsula by boat and eventually establishing permanent settlements. Fish and shellfish from Accomack fed the young colony, and salt distilled from seawater was a valuable preservative, enabling the settlers to survive winters when food was scarce.

So the waters surrounding Accomack provided both food and transportation. When inland settlements began and people started clearing land to grow crops, the produce was moved to market by ships that docked at many wharfs on seaside and bayside creeks. Most of these exist now as place-names only. Some examples are Pitt’s Wharf in northern Accomack, Boggs’ Wharf and Evans’ Wharf on Pungoteague Creek, Finney’s Wharf on Onancock, Davis’ Wharf on Occohannock Creek, and Burton’s Shore on the seaside.

After the railroad came through, people depended less on waterways for transportation, but the seafood industry in Accomack gained national attention. Salty Chincoteague oysters made the island famous. Terrapin stew was such a hit in city restaurants it nearly drove the animal to extinction, and speedy rail travel and refrigerated cars ushered in a new product for the seafood industry, freshly processed crab meat and soft crabs. The railroad also ushered in an era of tourism, with Northern visitors flocking to the sandy beaches in the summer and coming in winter for the superb waterfowl hunting.

Working on the water is still a way of life in Accomack, but most local residents think of a day in the boat as recreation. Sportfishing is an important aspect of tourism, and popular beaches such as Assateague draw hundreds of thousands of people each year. Visitors no longer come by rail, but the attraction has not changed. Few places in the East offer miles of ocean beach, great expanses of salt meadows, and plentiful seafood there just for the taking.

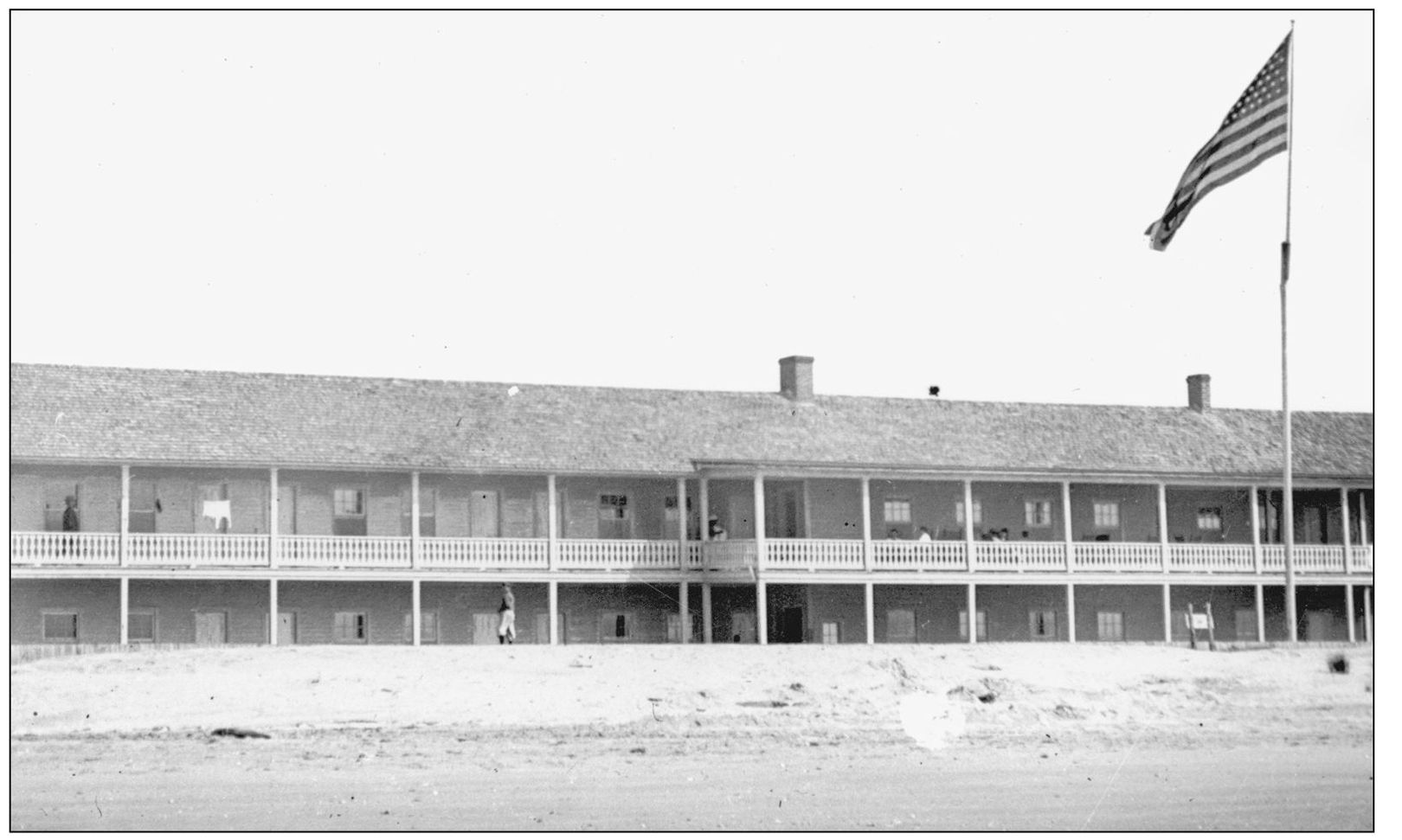

The clubhouse at Wallops was a rambling, two-story frame building. Accessory structures included staff housing, stables, boathouses, and a large pier and wharf. William Conant of Chincoteague was awarded an $8,000 contract to build the clubhouse in the summer of 1890. The consortium paid $8,000 for Wallops Island, which at that time was about a mile wide and 7 miles long. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

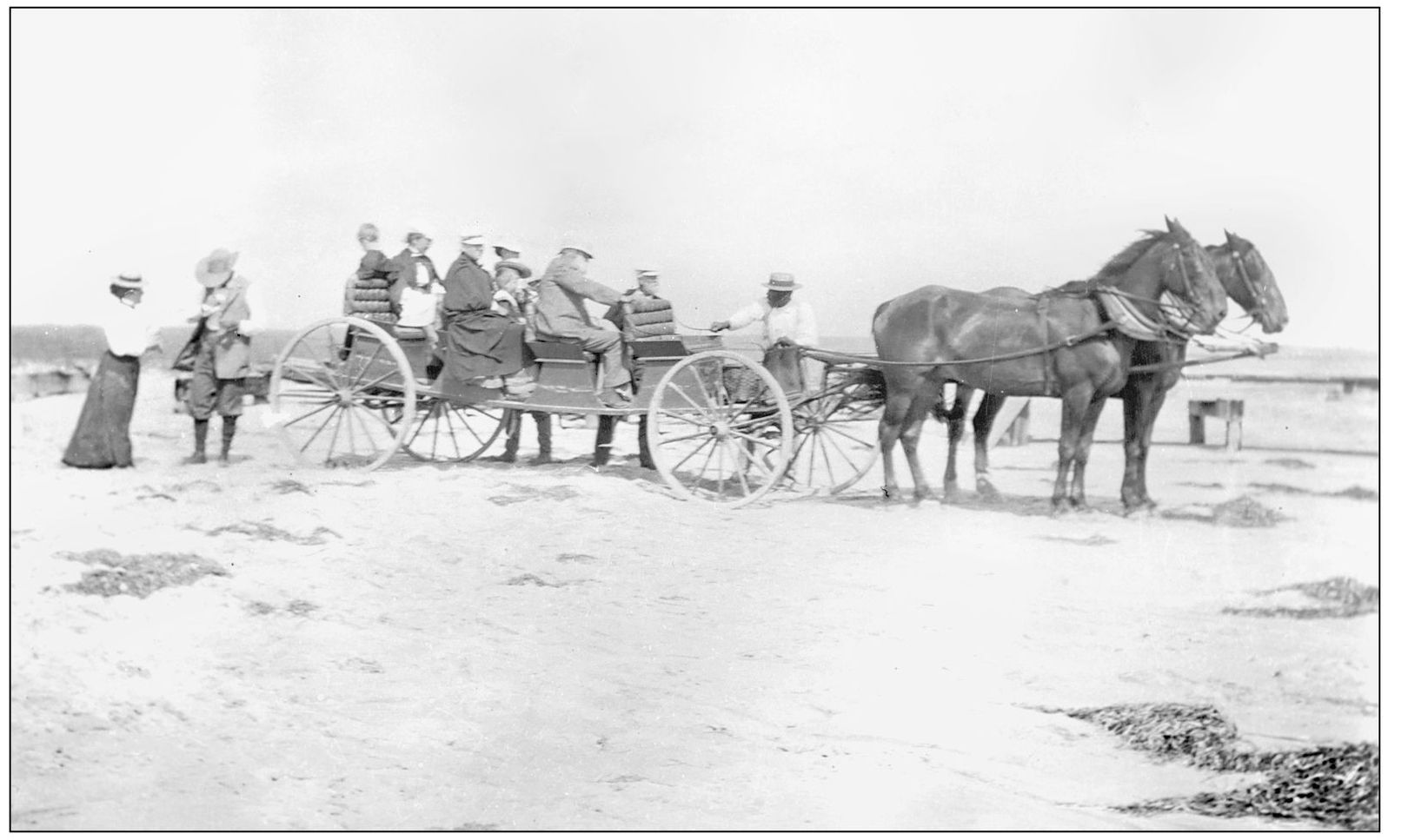

Guests at the Wallops Island Club traveled by the “dune buggy” of their time. The club had a flock of about 300 sheep, 100 ponies, and various other livestock. Nearby Chincoteague Island is famous for its annual pony penning, but in those days, Wallops had a similar event of its own. Newspapers advertised a sheep penning in June 1888, with a large number of sheep and lambs to be offered for sale. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

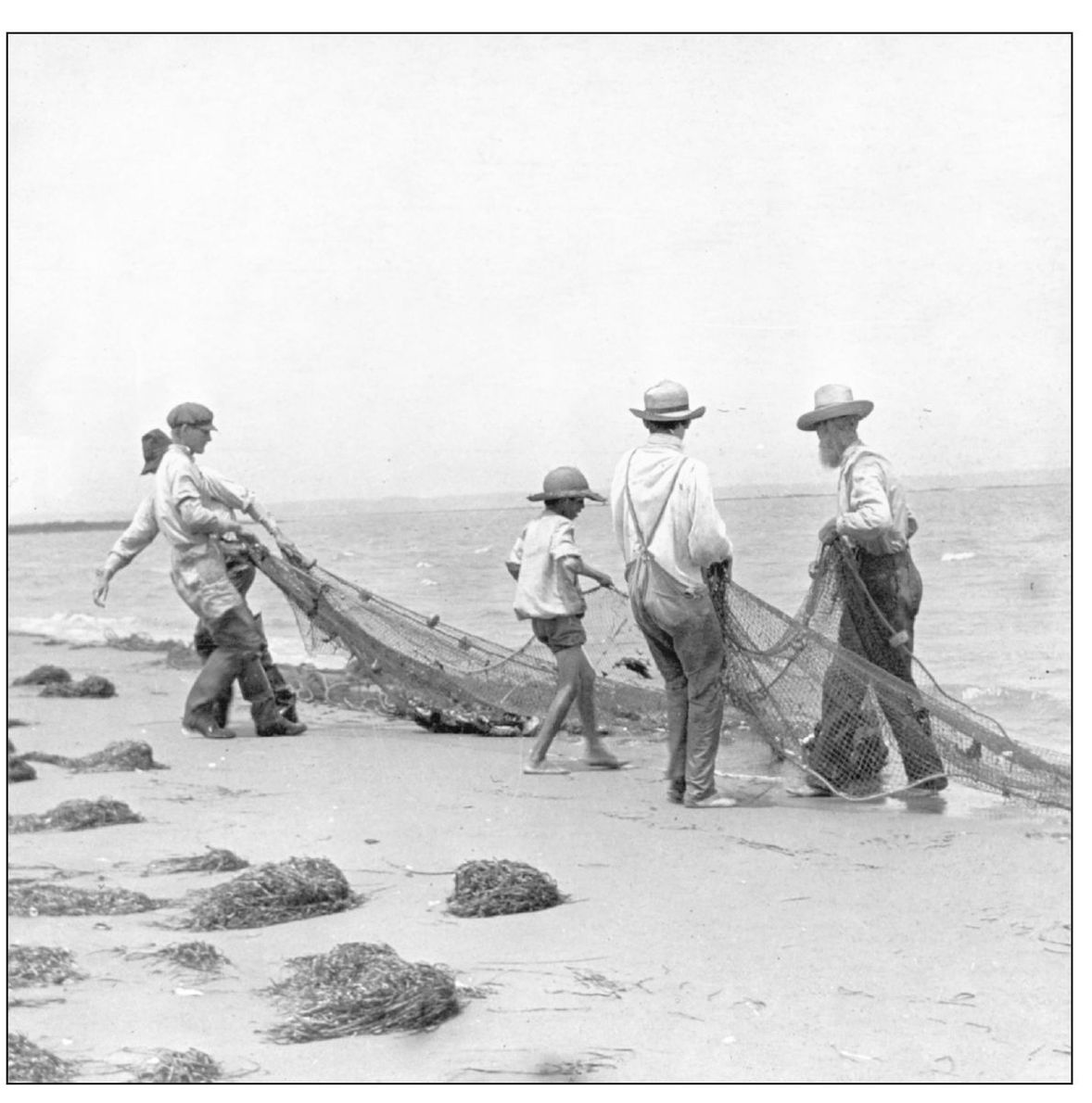

Dinner at the club usually featured fresh seafood, and guests of all ages participated in gathering it. Wallops was one of three clubs on the seaside of Accomack County in the 1890s. Others included the Accomack Club and the Revel’s Island Club, both near Wachapreague. Guests enjoyed fishing in the summer months and waterfowl hunting in winter. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

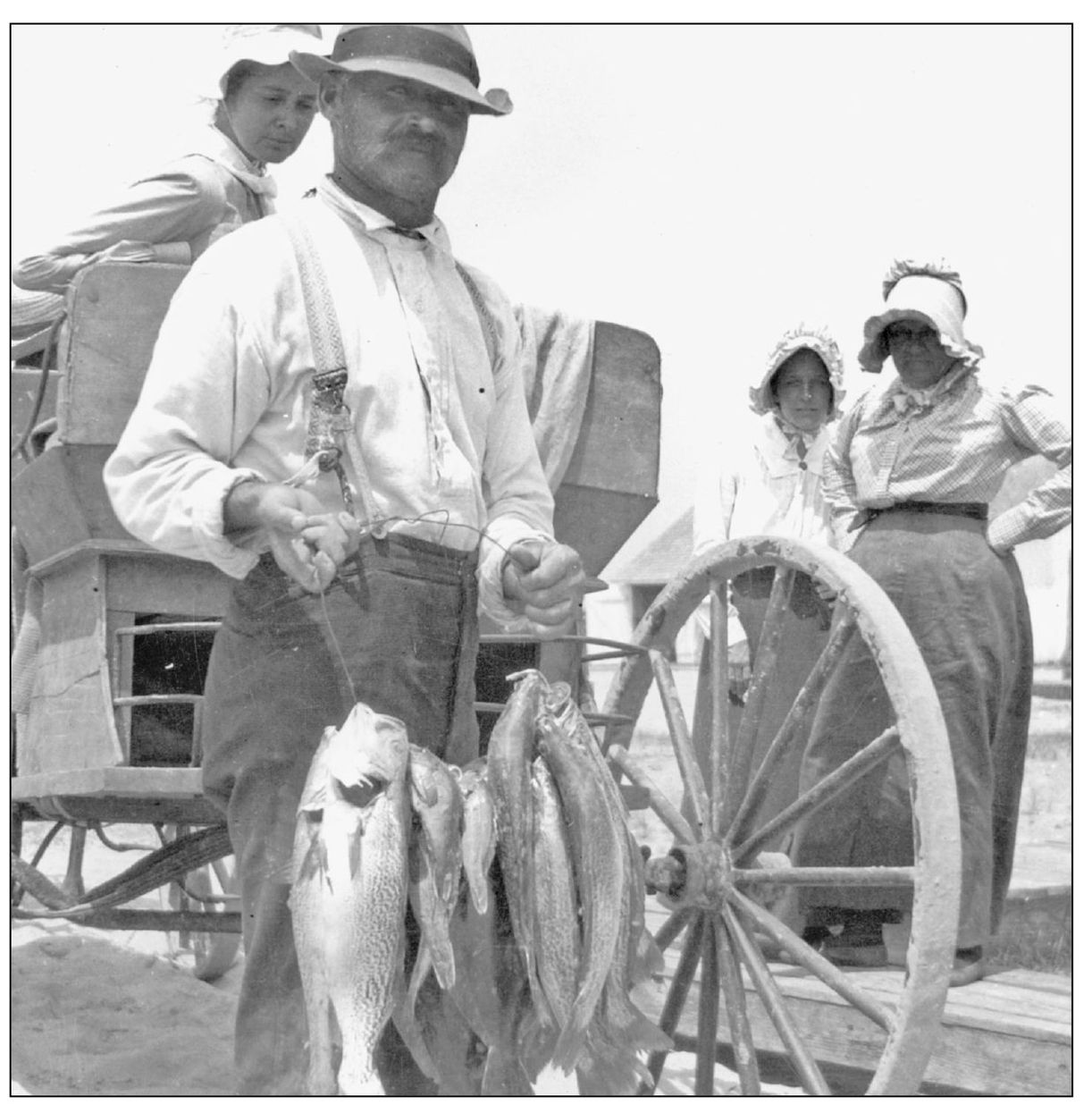

On the menu tonight are sea trout, croakers, and possibly spot. While club guests helped gather the catch, the kitchen duties were left to the paid staff, who lived full-time on the island during the summer season. The everyday business of the club was conducted by a manager. One of the longest tenured was Benjamin Franklin Scott, who served until 1906, when he left to open a dairy business on Chincoteague. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

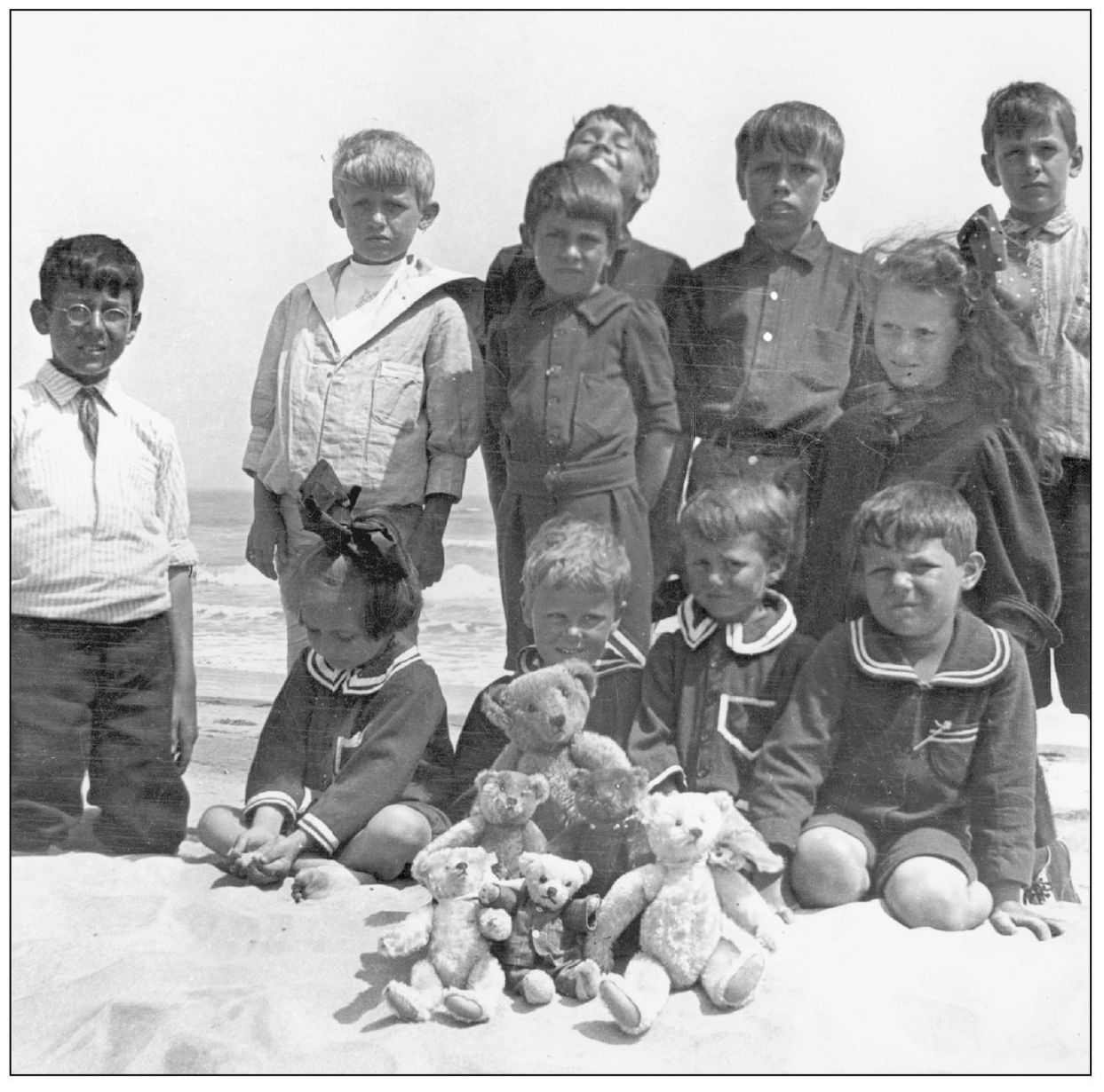

Toy collectors would be envious of the Steiff bears on display in this photograph. A visit to the Wallops Island Club was the highlight of the summer season for the children of club members. In many cases, wives and children would come to the island for the entire summer, while the men attended to business in the city, taking breaks of a week or two to enjoy the shore. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

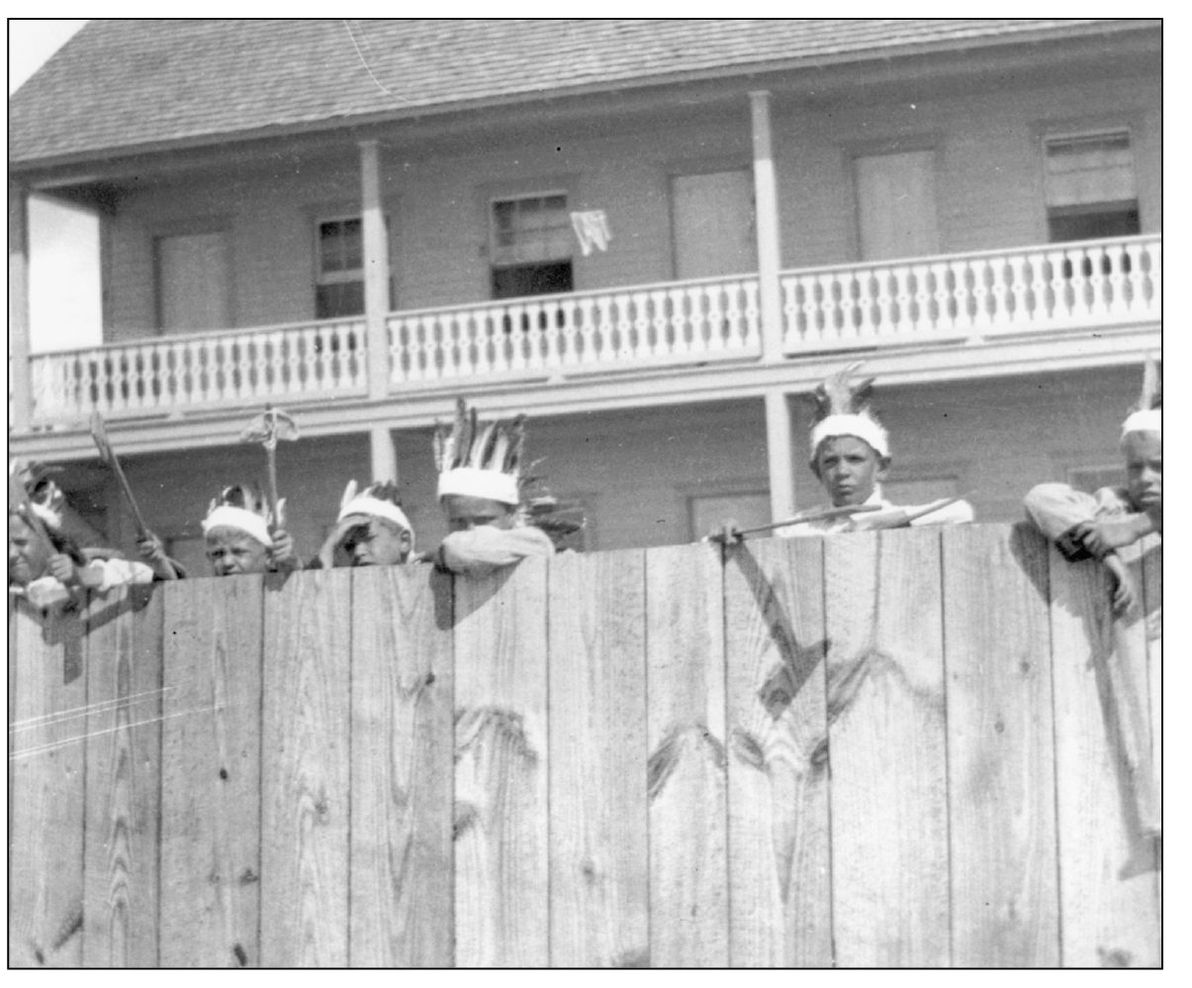

Fishing and exploring the beach could take up only so many hours in a young person’s life at the Wallops Club. These children enjoy a game of cowboys and Indians, complete with homemade headdresses and tomahawks. A close look at the tomahawk on the left reveals that it was made with an oyster shell, an appropriate weapon for an island Indian. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

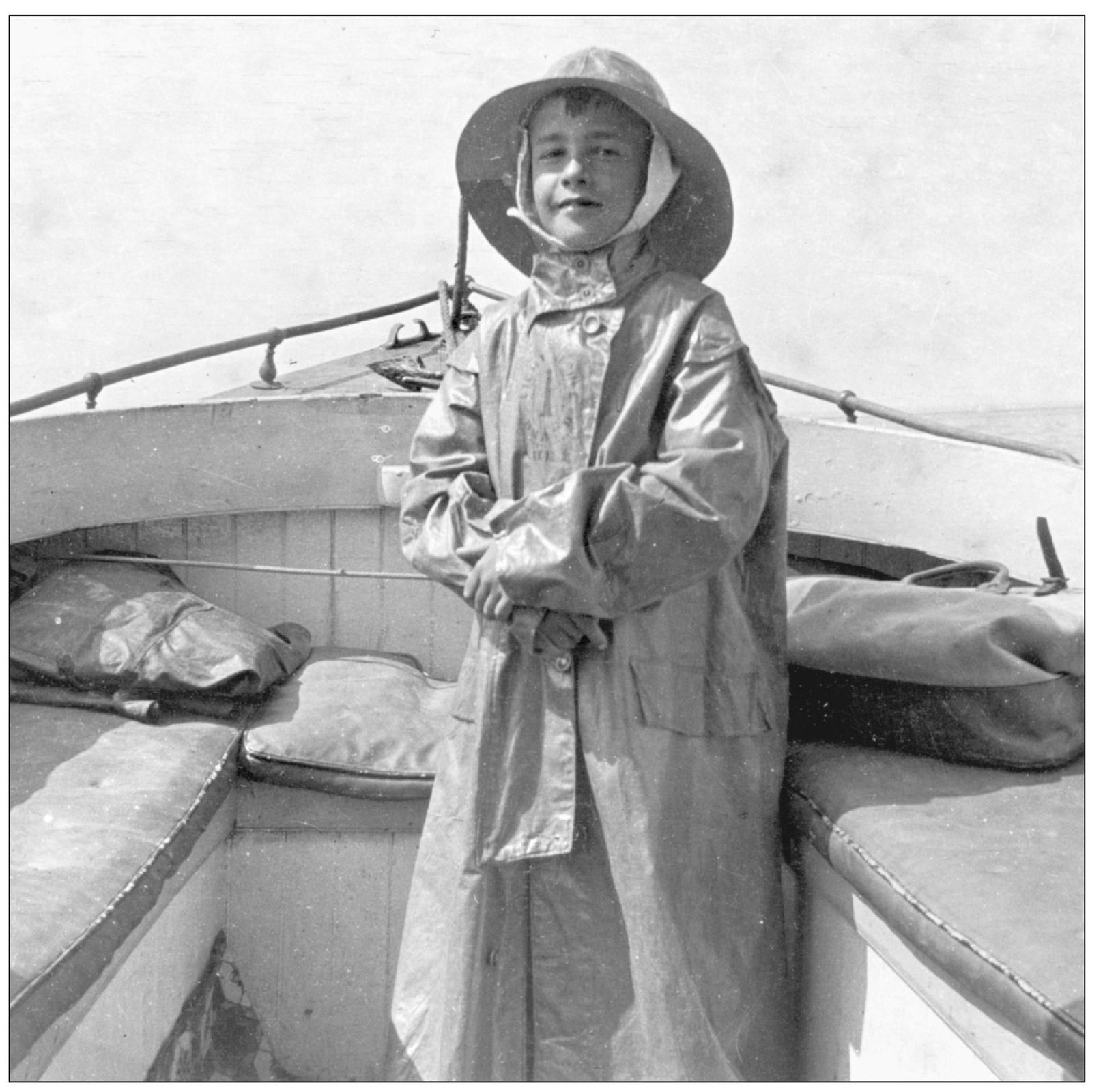

This young man in his oilskin was taking one of the club’s launches between the island and the mainland Eastern Shore. These remarkable photographs were taken by Robert Stout, a club member from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, during the first decade of the 20th century. The original negatives were donated by the Stout family to NASA Wallops in the 1990s, and NASA made prints for the ESVHS and the Eastern Shore BIC. Many are currently on display at the center’s museum in Machipongo. They are remarkable because they show not only the barrier island landscape, but they also depict people enjoying the beach, the ocean, the boats, and each other, a wonderful visual record of life on these barrier islands. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

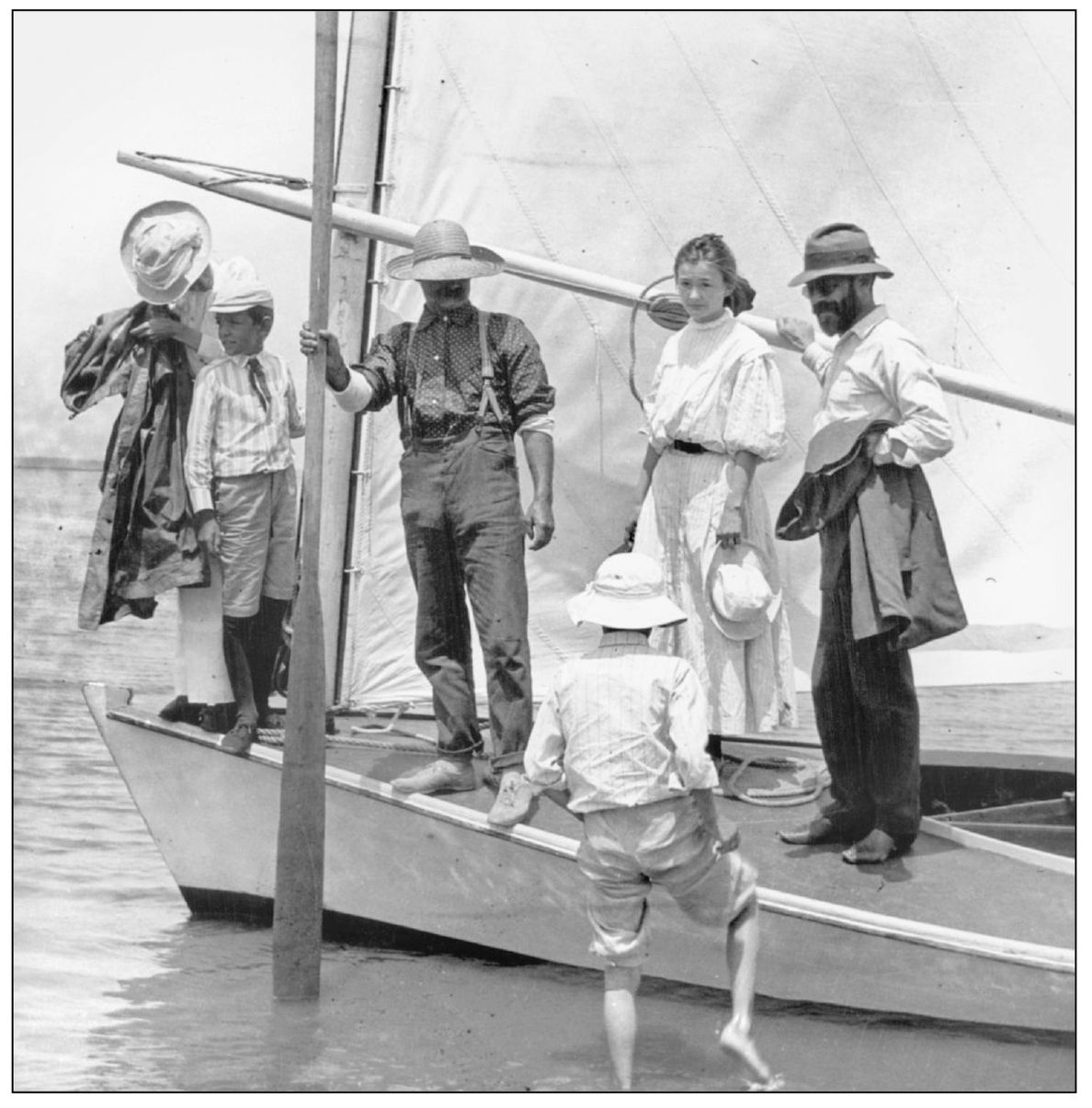

Boats served as the conveyance of the day at Wallops. They ferried guests to and from the island, and they were used for fishing and for pleasure. This group had no luggage so it was probably heading out for a day-sail. The large oar being held by the man in the center was used by women to get on and off the boat without getting their dresses wet. The boat would get as near as possible to the beach, the woman would grab the oar, and then swing out on it toward shore. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

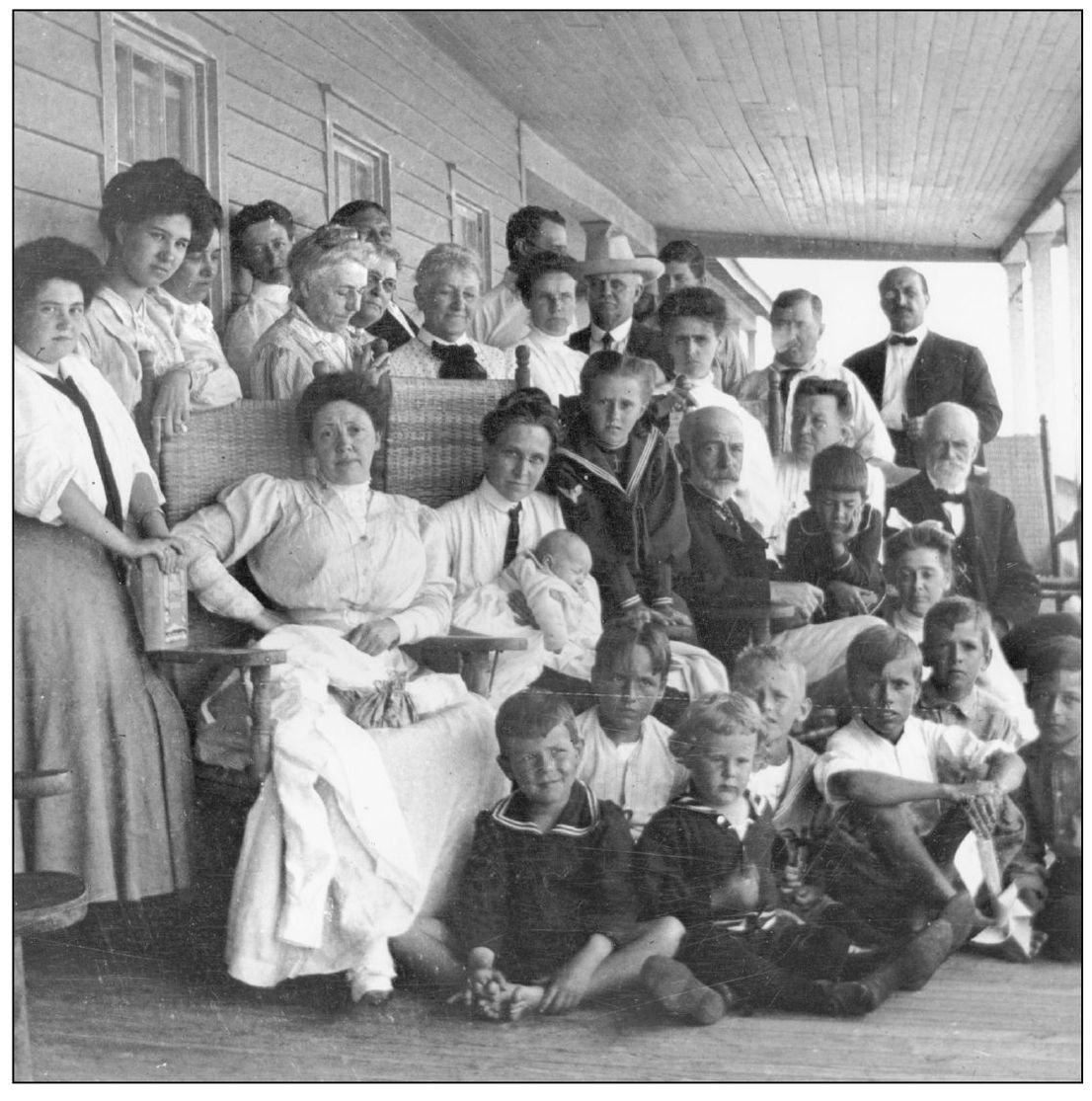

Club guests gathered on the porch for a group photograph around 1905. The majority of the members were businessmen from Pennsylvania. Newspaper accounts from 1897 report that a group of men led by O. Beecher of Pine Grove and W. K. Woodbury of Pottsville bought the island from Capt. John W. Bunting, a prominent Chincoteague businessman, and other shareholders. The Wallops Island Association was chartered in 1899 and held annual meetings until the group dissolved nearly 60 years later. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

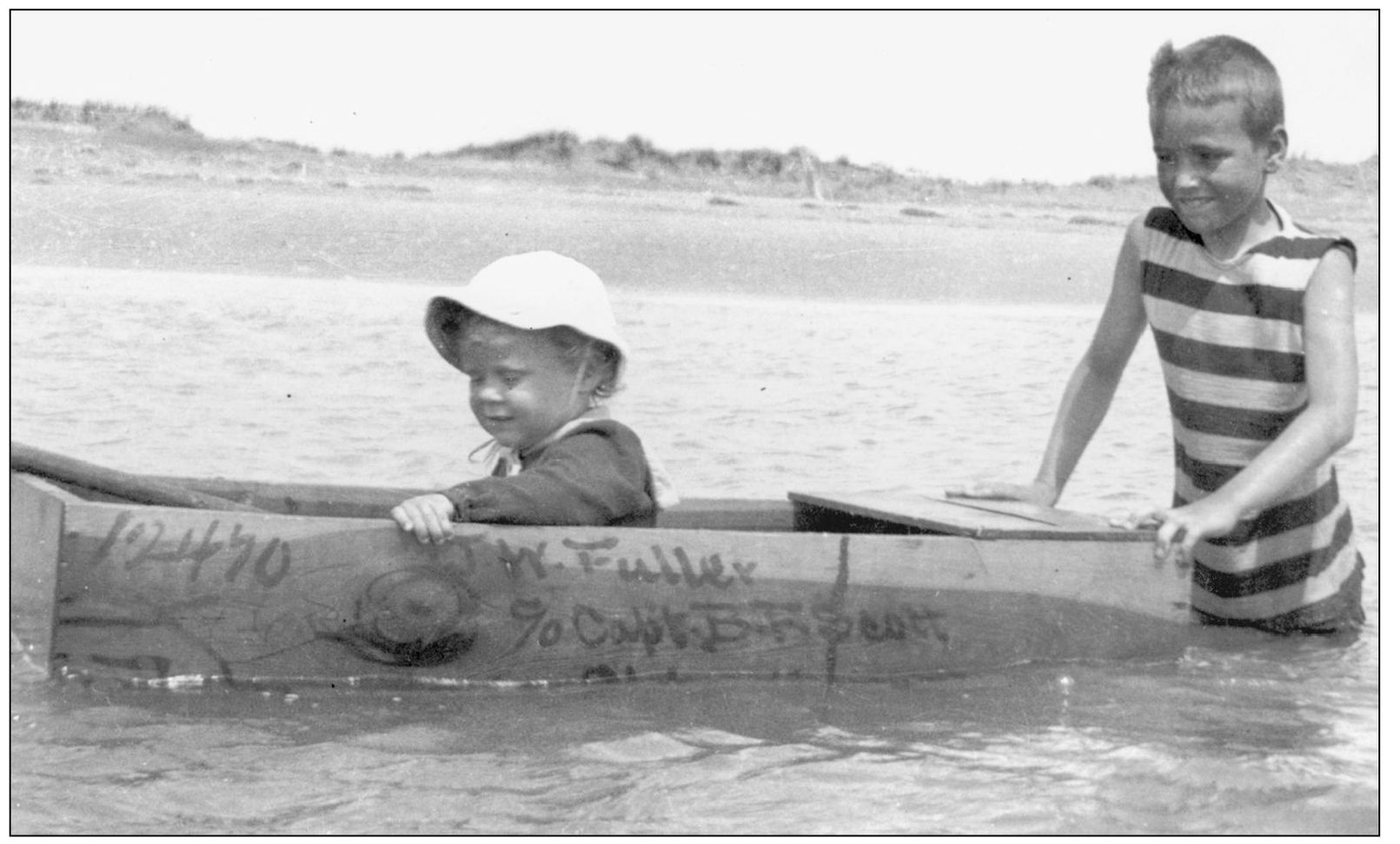

Wallops Club children provided a great example of early-20th-century recycling, turning this wooden shipping crate into a fine boat. The crate is addressed to club member J. W. Fuller in care of Capt. B. F. Scott, the longtime caretaker who lived in a cottage on the island prior to construction of the clubhouse. Scott later moved to Chincoteague and became something of an island legend. He died in January 1944 at age 105. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

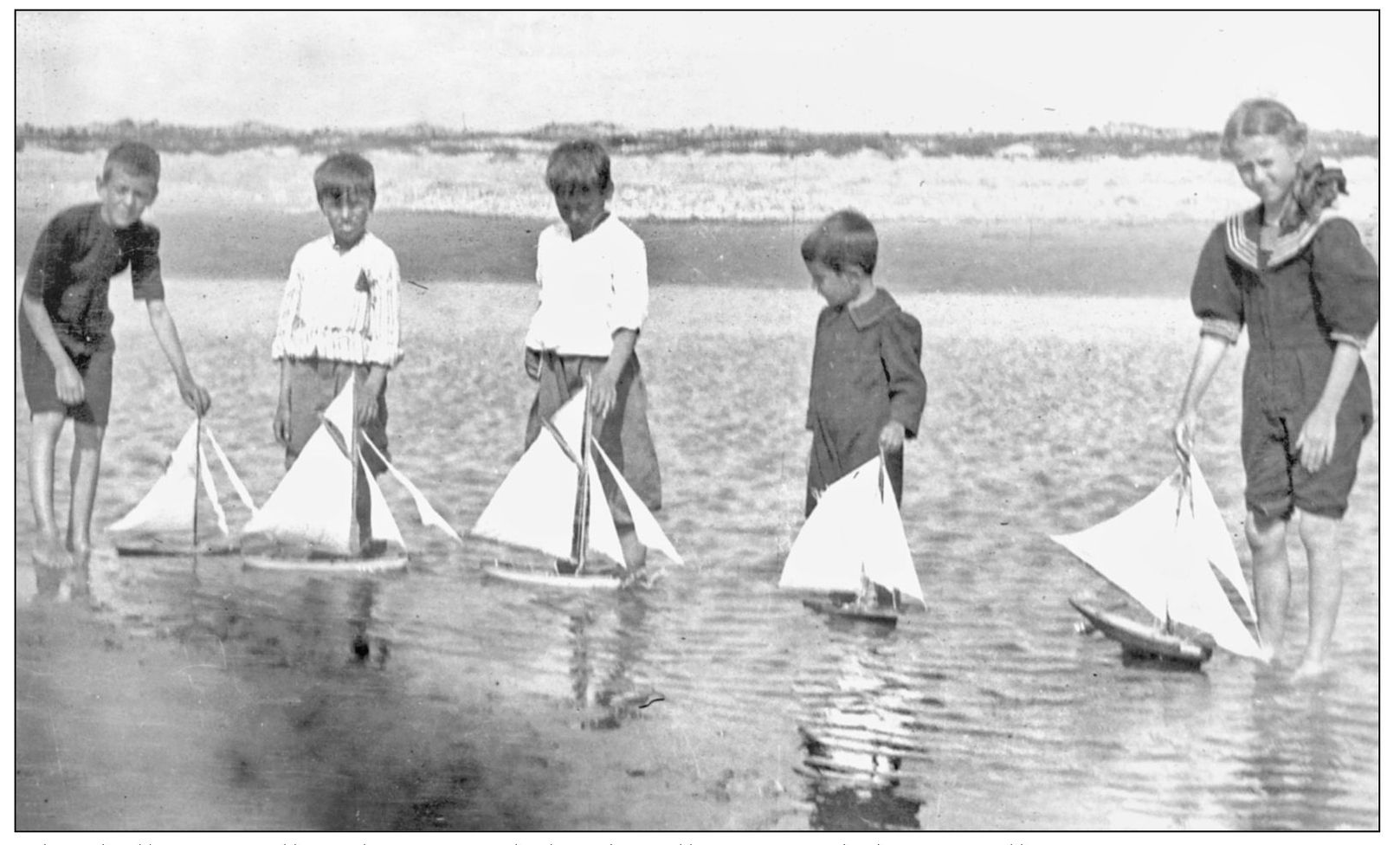

The shallow, usually calm waters behind Wallops provided an excellent venue for trying out toy sailboats. These boats were probably made by hand and, like models of today, were copies of full-size versions that were popular with boaters. As this photograph attests, model boating was not a sport strictly for boys. The girl on the right has one of the more elaborate rigs of the group. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

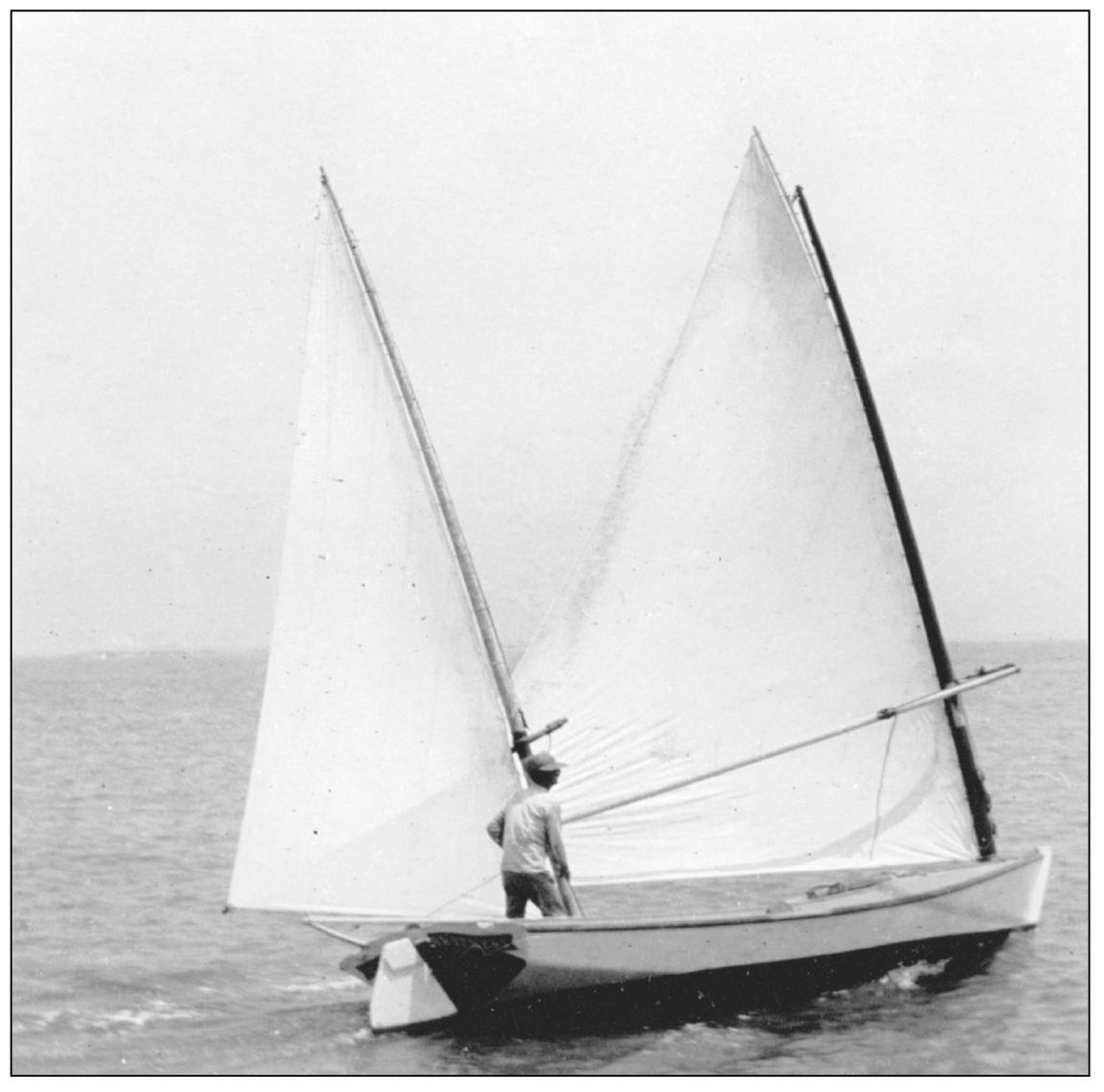

Sailboats were an everyday mode of travel when this photograph was taken around 1905. But graceful sailboats such as this are great examples of the theory of form-follows-function. The best boatbuilders were artisans whose works not only performed an everyday function, but whose craft also were pleasing to the eye and a joy to use. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

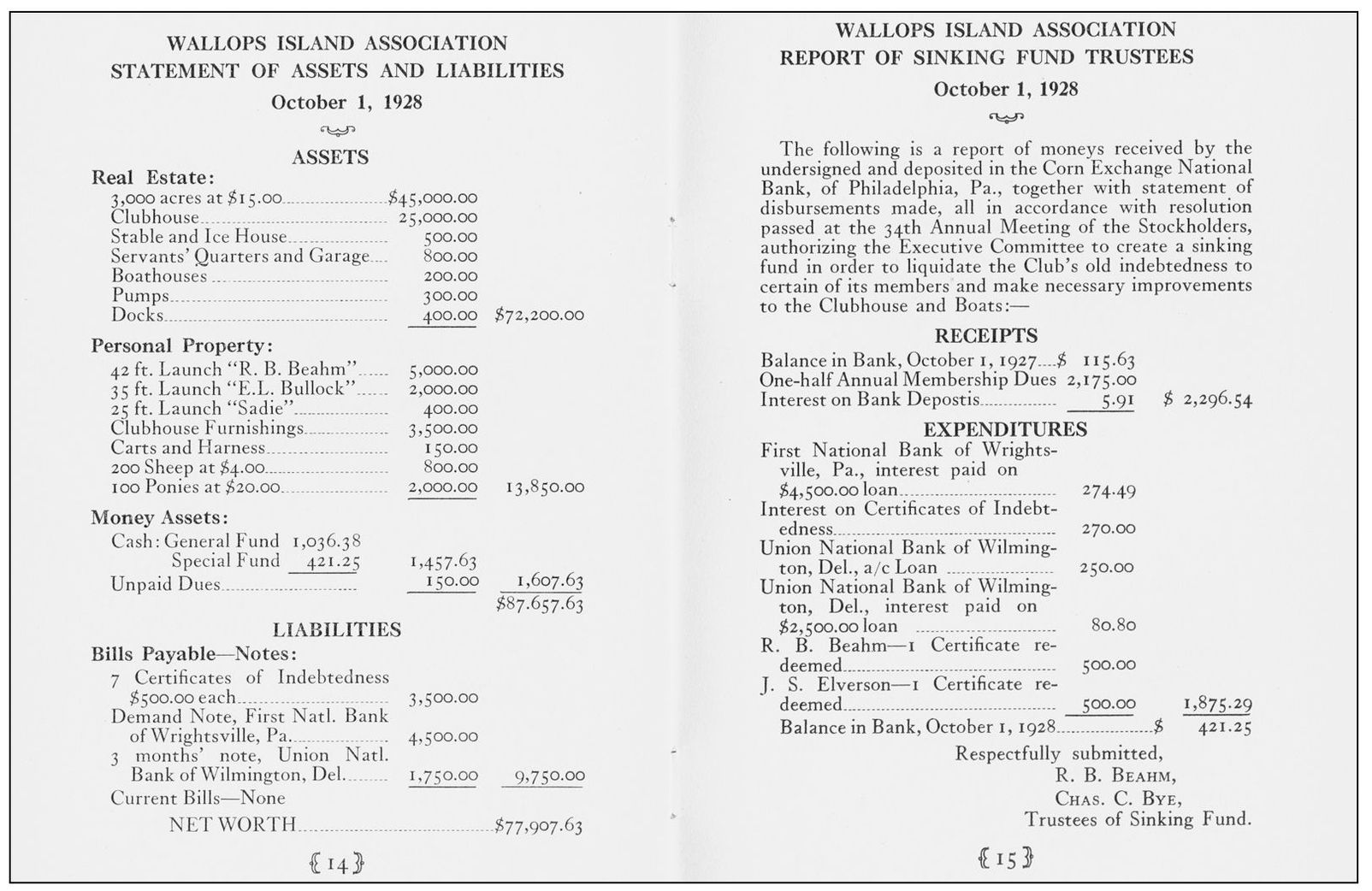

The Wallops Island Association was founded and run by businessmen, so it is not surprising that the group was governed like any good corporation. The shareholders held annual meetings, voted on business matters, approved budgets, and elected officers. This is a statement of assets and liabilities presented at the annual meeting of 1928, held at the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

These photographs, made from original negatives more than a century old, provide a wonderful record of what life was like on Accomack County’s barrier islands. Those who frequent these barrier beaches today find the costumes amusing. Women dressed head to foot in dark outfits had to have suffered from heat, and as for men wearing neckties to the beach, it is a scene not often encountered today. The clubhouse at Wallops has been gone for generations, a victim of storms and a rising sea, and the role Wallops plays today has to do with space exploration, not recreation. Fortunately, these photographs document an era that is part of its history. (Stout family, courtesy of NASA Wallops.)

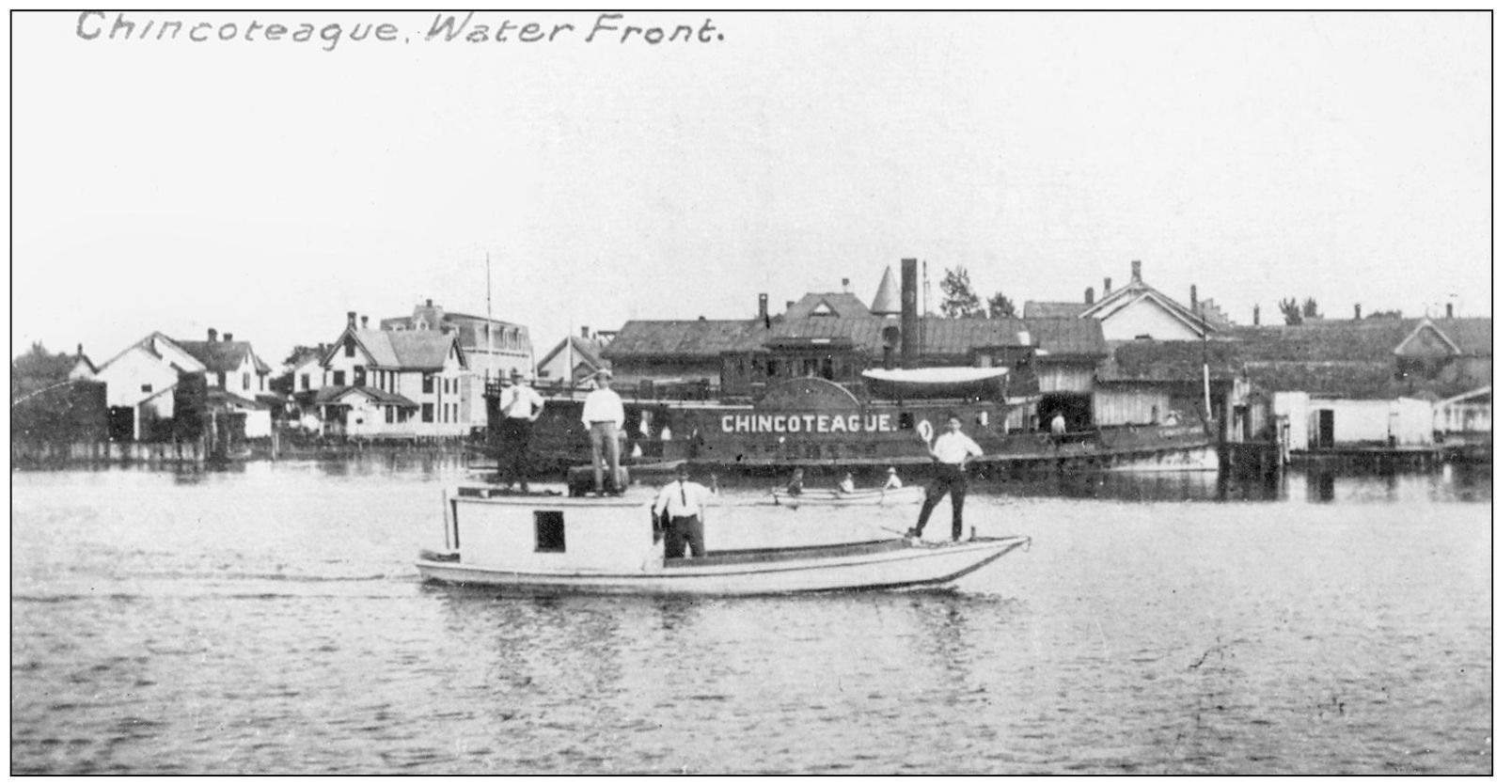

Chincoteague Island is a community whose history is centered on the water. Here a traditional Chincoteague scow workboat is shown in this early-1900s photograph. A cabin has been added to provide shelter for watermen during winter months. In the background is the side-paddle steamer Chincoteague, which ferried passengers and goods between the island and Franklin City, near Greenbackville. (Courtesy of Dino Johnson.)

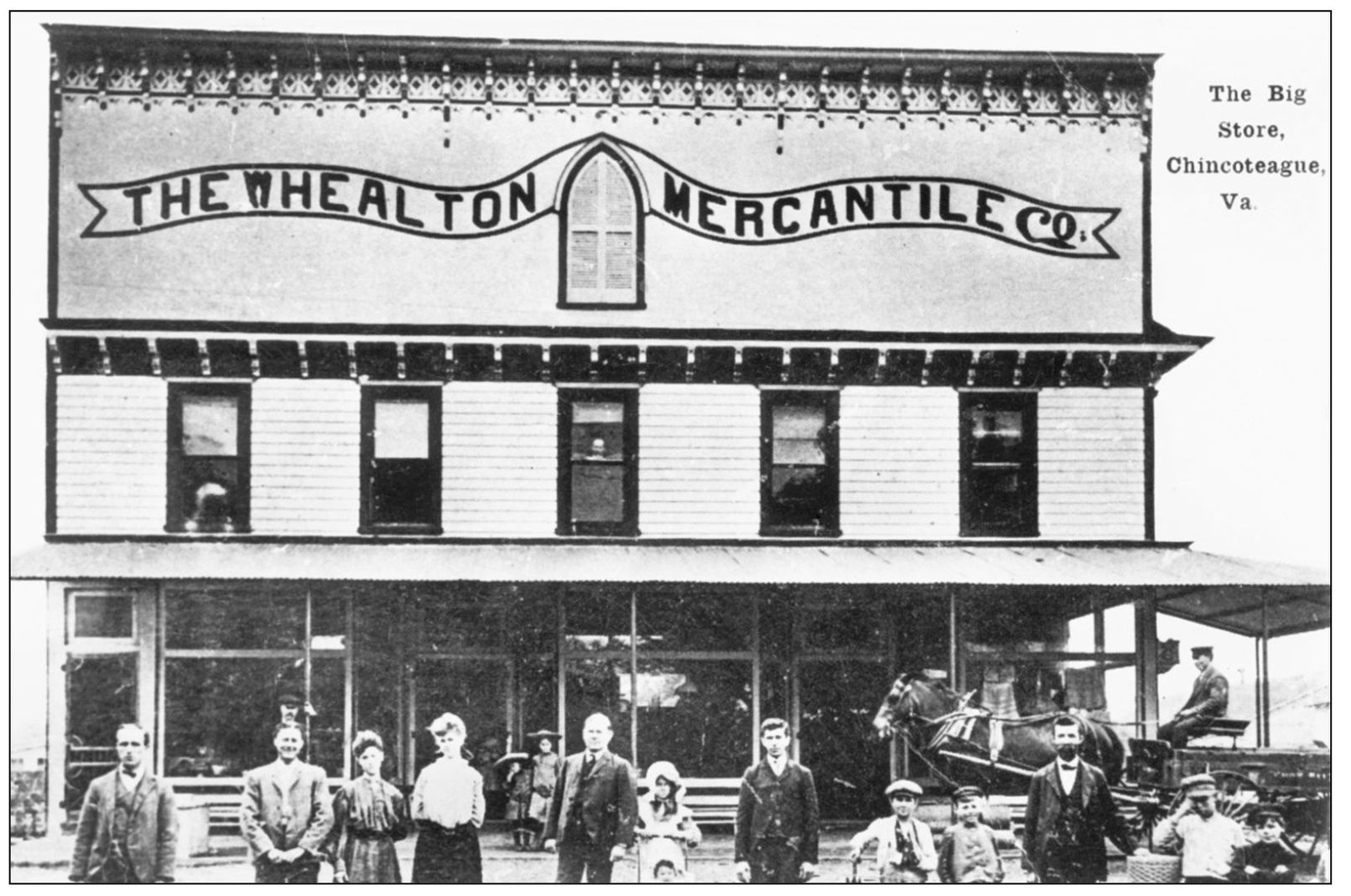

J. A. Whealton’s general store on Main Street in Chincoteague was known as the Big Store and was one of the largest retailers in Accomack County in the early 1900s. It was destroyed by fire in 1924. Pictured here are, from left to right, John Anderton Jr., Edward Gillis, Harry White, Annie Timmons, Flossie Messick, Marion Marshall, Elizabeth Coulbourne, Clayton Richardson, Nora Baker, Wilbur Twilley, Dr. Charles Turman, Robert Holston, B. H. Hurdle, Joe Baker, Vincent Tolbert, William Munger, and Jay Smith in the wagon. (Courtesy of Christ United Methodist Church.)

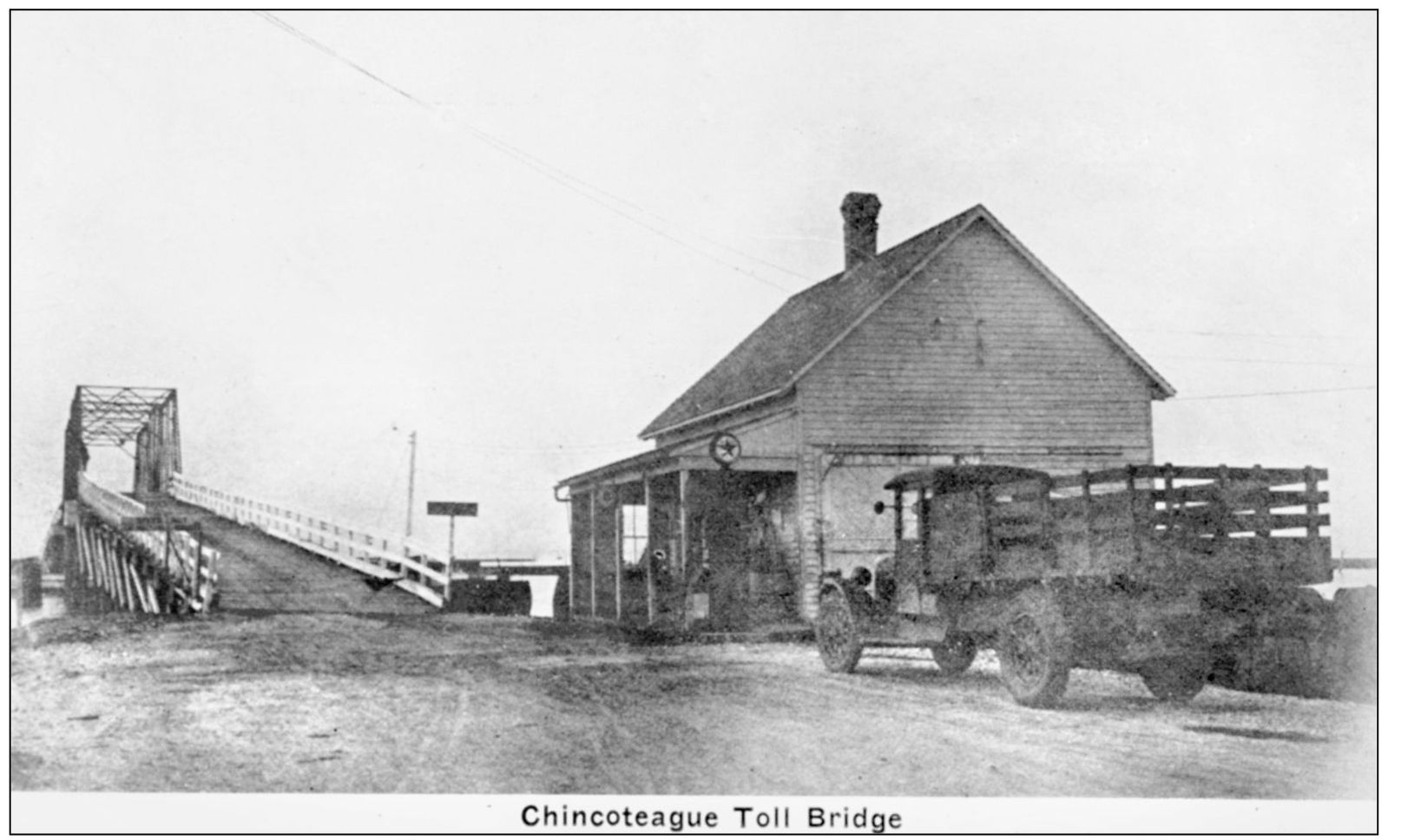

Chincoteague’s toll bridge and causeway, built by John B. Whealton, opened to traffic in November 1922, with dignitaries coming from all over the state to commemorate the opening of the span. The causeway was built from dredge spoil and shells, and was often treacherous during rainy periods. The state took over the roadway in 1930, paved it, and eliminated the toll. This is the bridge as it enters Main Street in downtown Chincoteague. (Courtesy of Dino Johnson.)

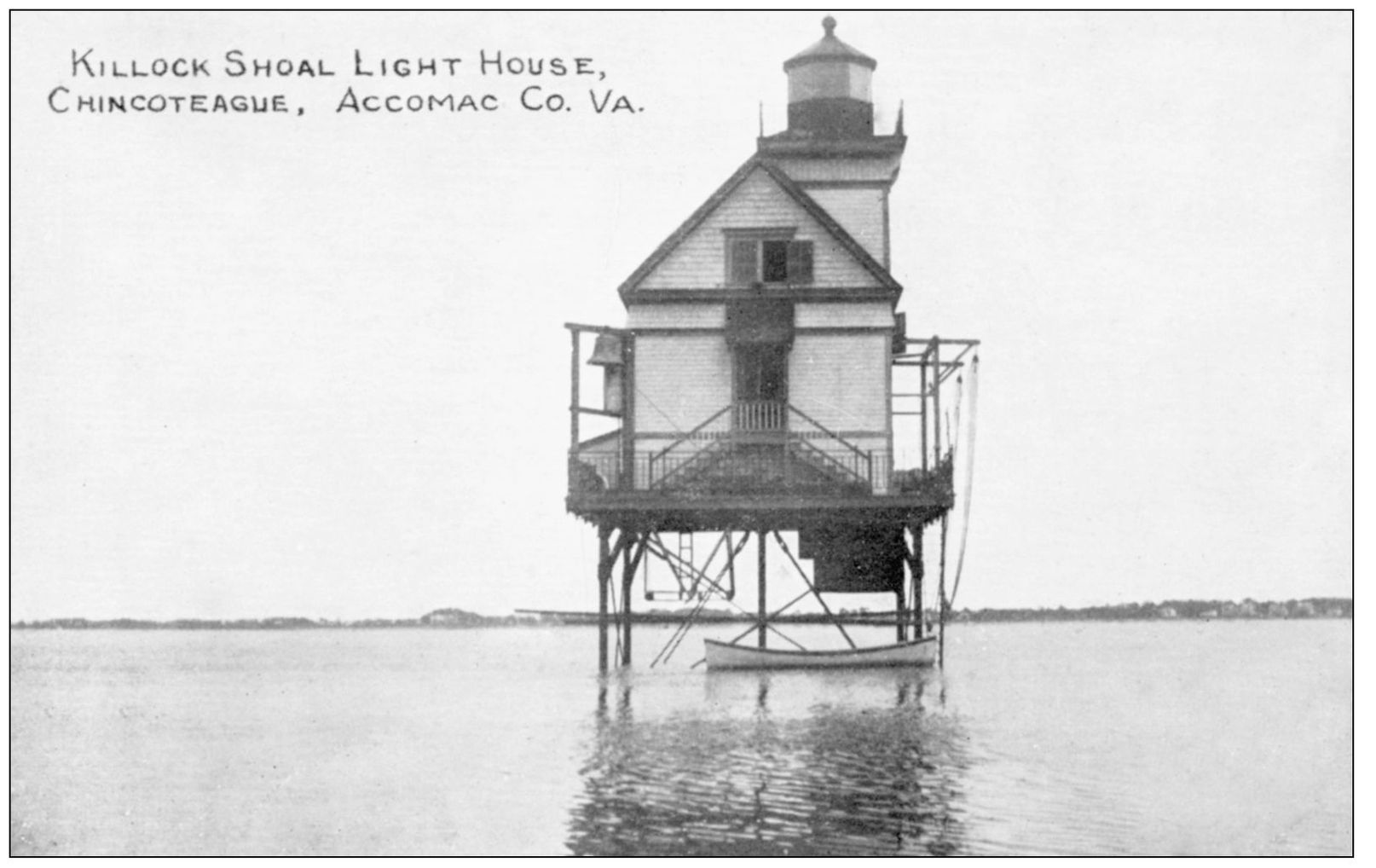

The Killock Shoals lighthouse opened in 1876. The light was located west of Chincoteague, marking the channel between the island and Franklin City. The railroad ran to Franklin City, and a steamship made regular trips to Chincoteague. The lighthouse was decommissioned in 1939. (Courtesy of Dino Johnson.)

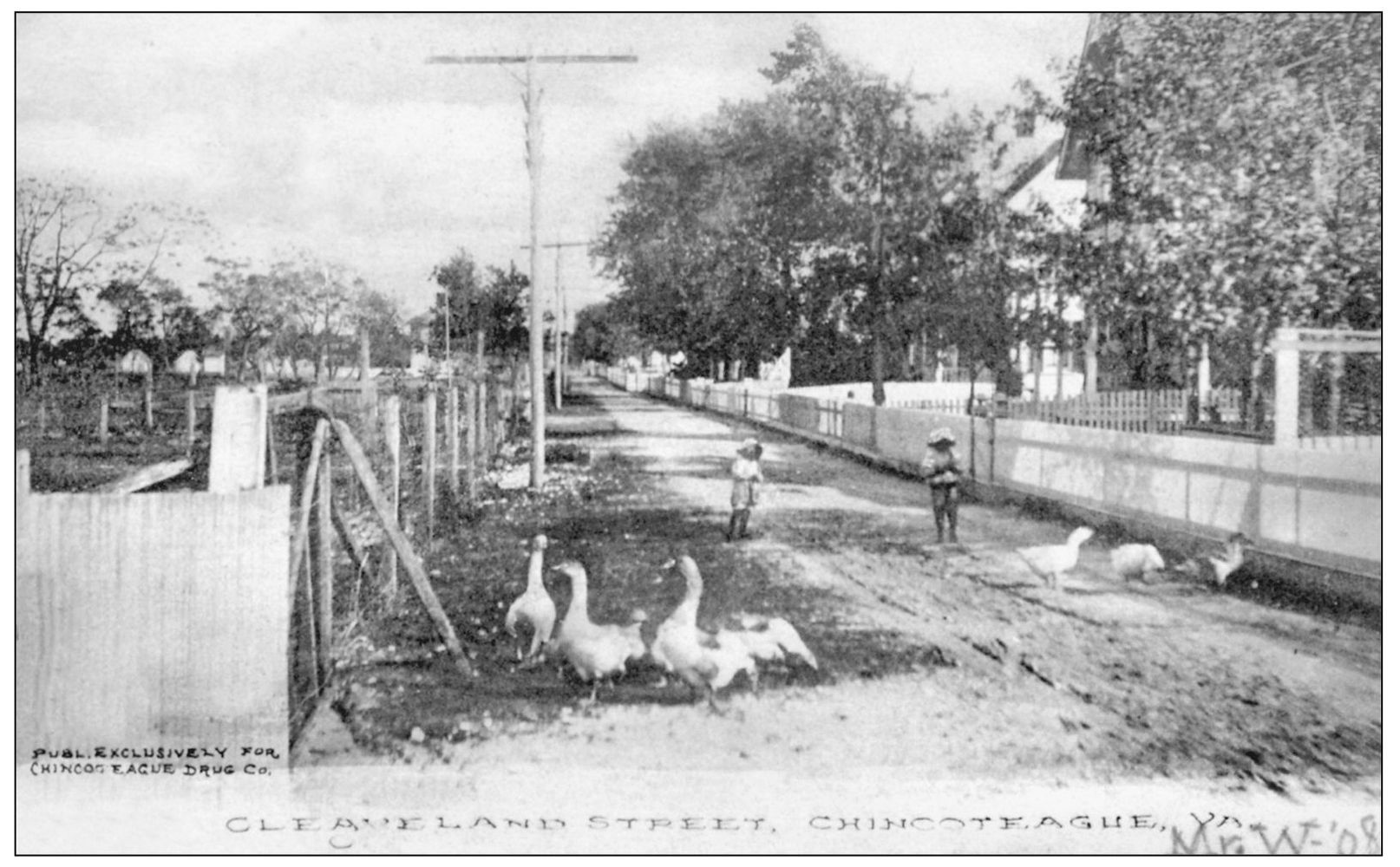

Cleveland Street in Chincoteague was a quiet residential neighborhood in 1908, with white picket fences, a tree-lined street, and barnyard geese sharing the sandy roadway with children. The area to the left, apparently an orchard in 1908, is the site today of the Fresh Pride grocery market. (Courtesy of Dino Johnson.)

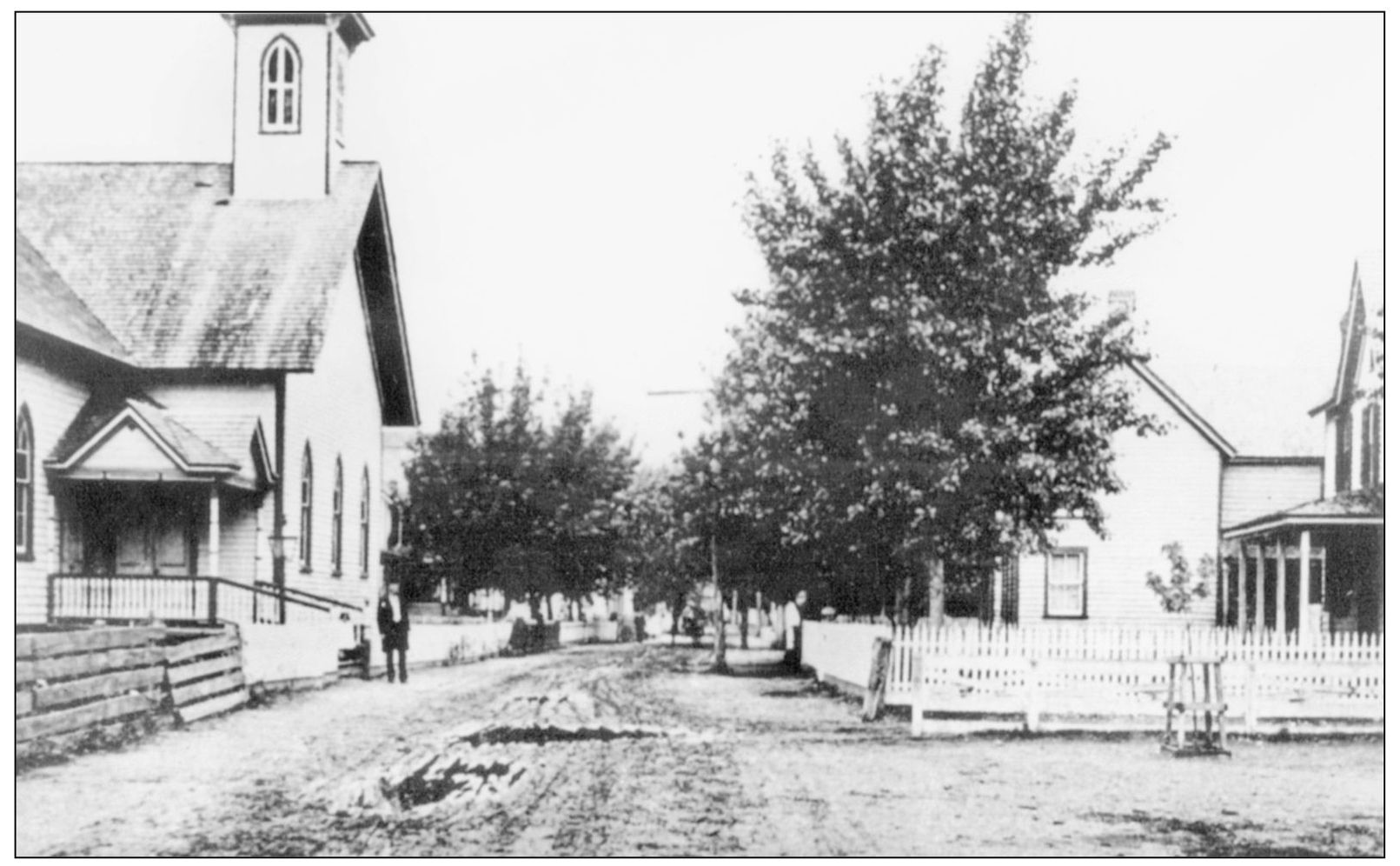

The church on the left in this 1906 photograph of Chincoteague was the Bethel Methodist Protestant Church. The original building was constructed in 1853 on Church Street, and in 1887, it was replaced by this structure. The church has had many different congregations over the years, and in World War II, it served as a lunchroom for school students and temporary housing for soldiers. (Courtesy of Dino Johnson.)

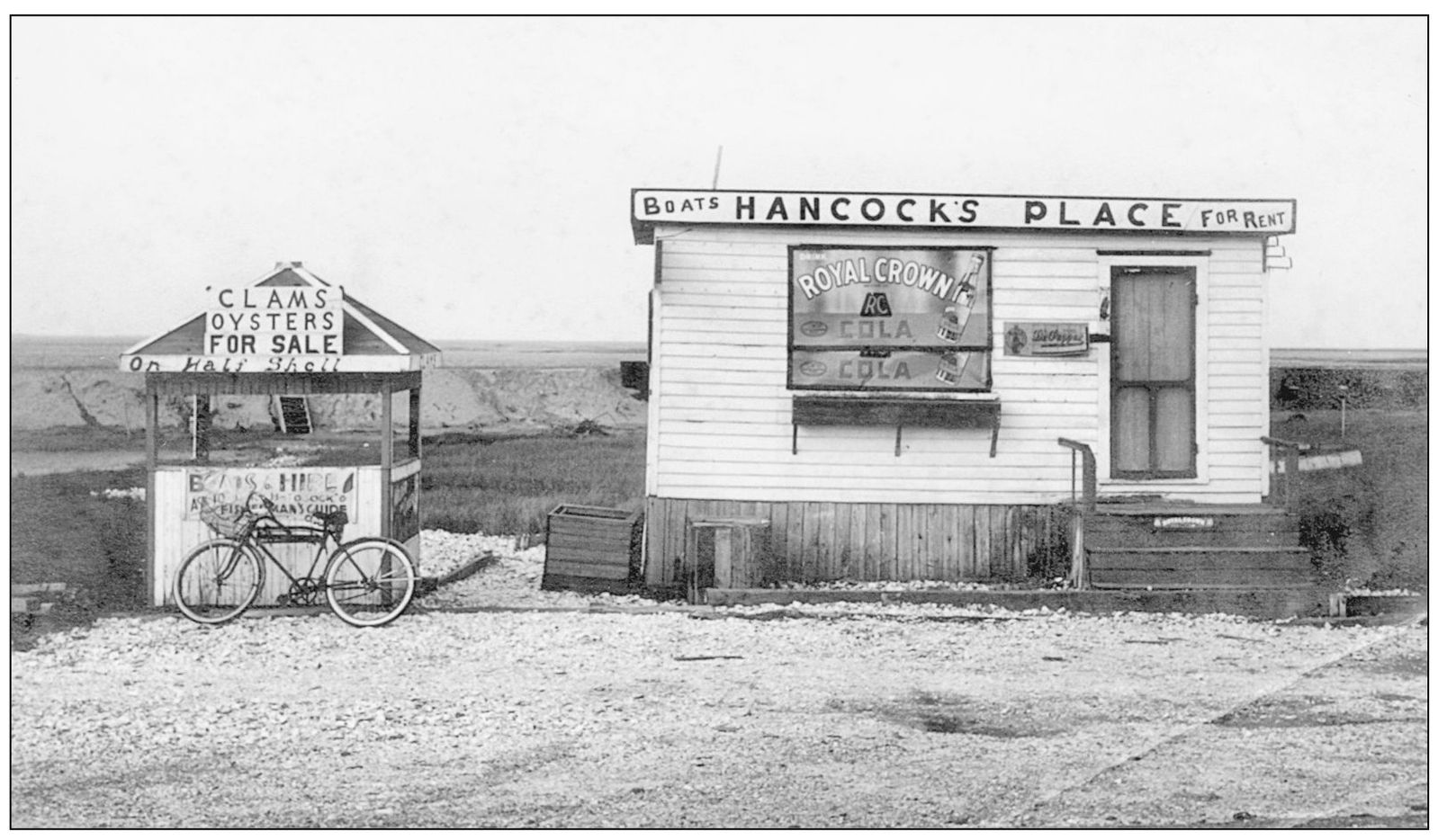

Chincoteague has for years been known for its seafood, especially those salty, sweet Chincoteague oysters that have always been much in demand. But sportfishing has been an important part of the local economy since the days of reconstruction. This little business, Hancock’s Place on Queen’s Sound, took advantage of both seafood and sportfishing. The stand on the left advertised oysters and clams on the half-shell, while the larger building offered boat rentals for visiting fishermen.

(Courtesy of O. W. Mears.)

Saxis Island, like Chincoteague, was off the beaten path, but it was an important base for commercial fishing. Saxis is located on the opposite side of the county from Chincoteague, on Pocomoke Sound and the Chesapeake Bay. Saxis was a busy port when the oyster fishery was going strong, and in more recent years, watermen have focused on blue crabs and fish. (Robertson Collection, courtesy of ESVHS.)

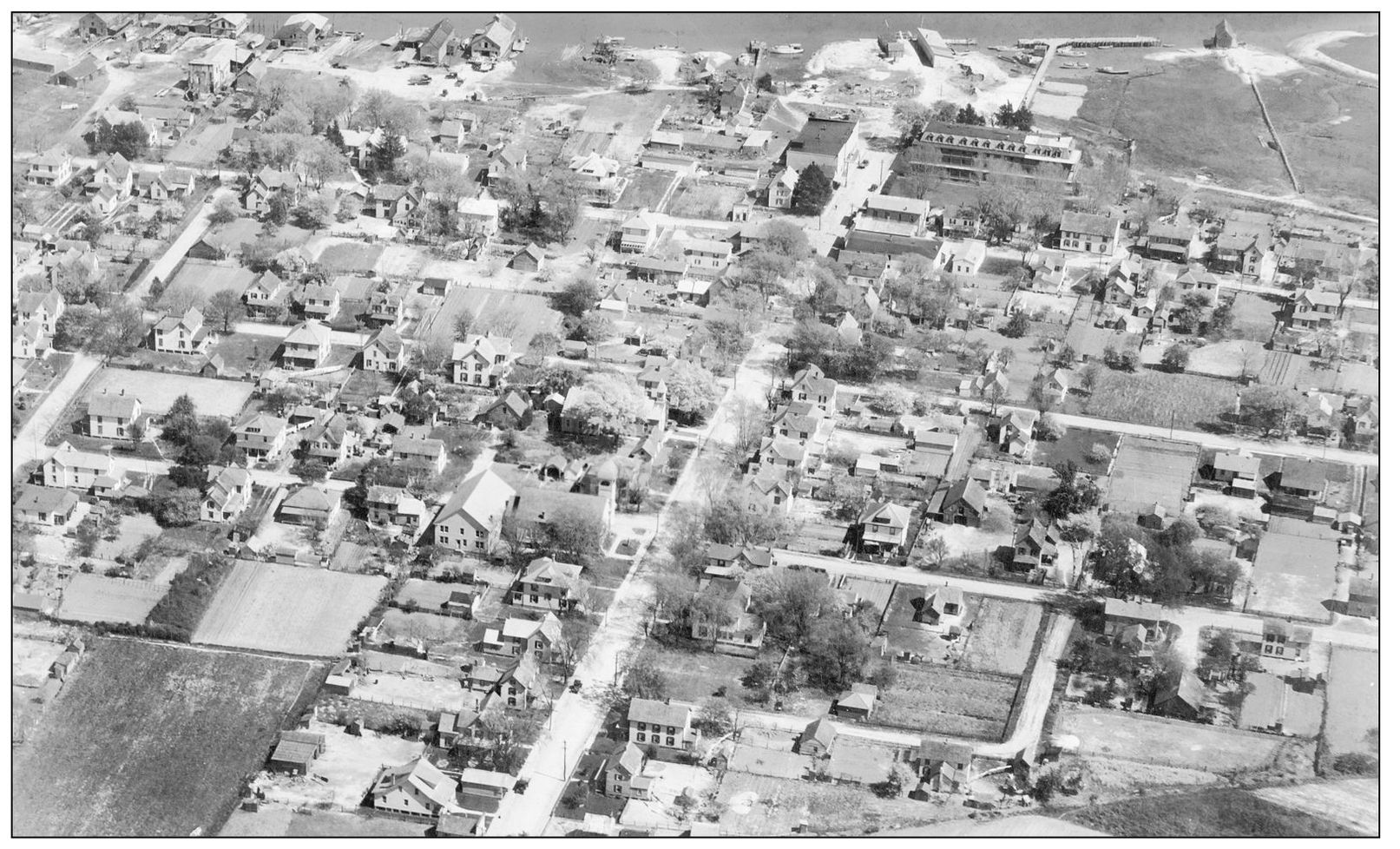

This aerial photograph shows the town of Wachapreague around 1940. The Hotel Wachapreague is at the top right, with a walkway leading to a large pier. The fish packinghouses are along the waterfront to the left of Main Street. Wachapreague was originally known as Powelton, but when an application was made for a post office in 1884, it was discovered that Virginia already had a Powelton, so a name change became necessary. (Photograph donated by L. Floyd Nock, courtesy of ESVHS.)

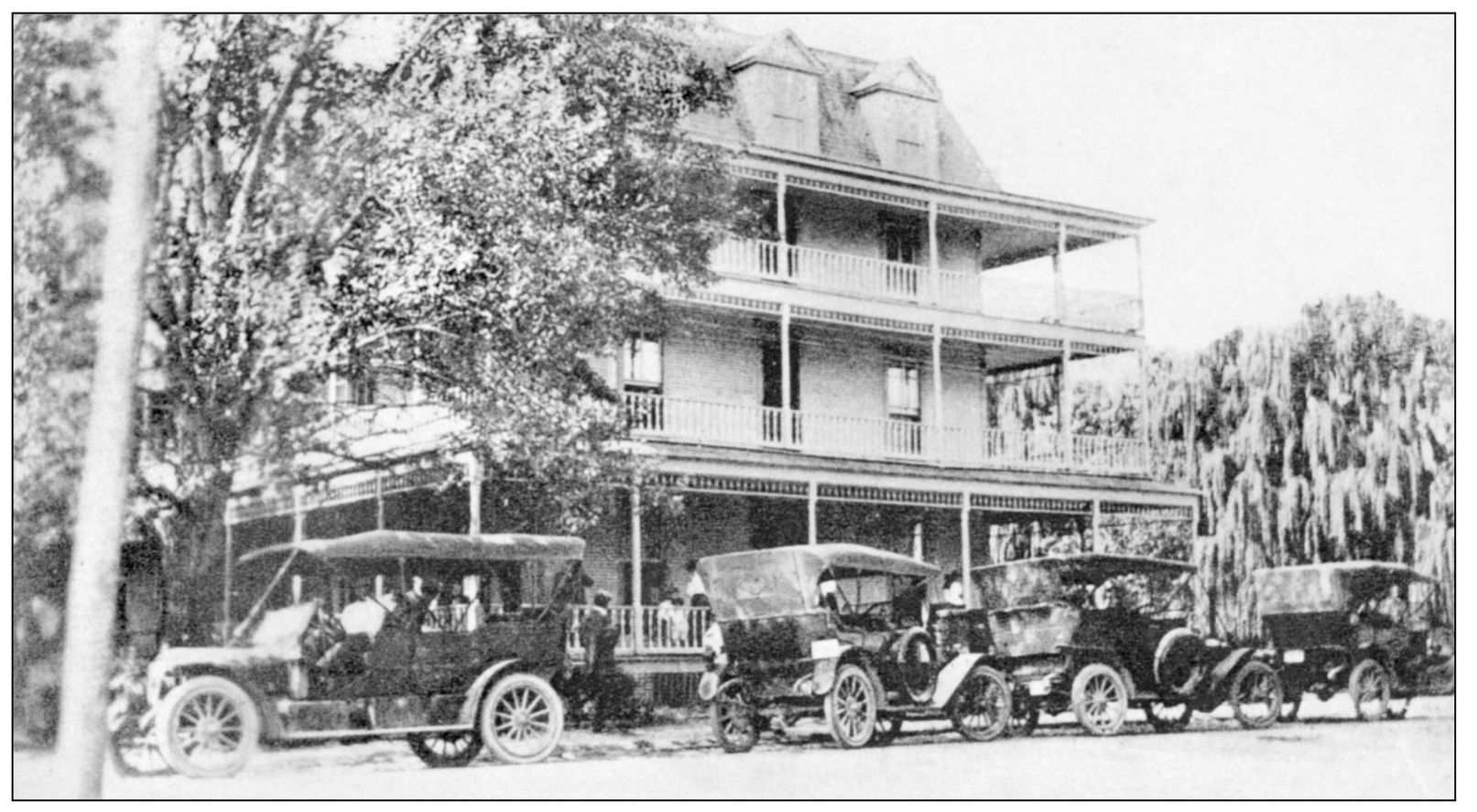

Hotel Wachapreague was built in 1902 by A. H. G. Mears, a local businessman, who reasoned that the nearby railroad, ocean beaches, and excellent sportfishing would combine to attract tourists to a well-appointed hotel. He was right. Hotel Wachapreague and the Island House on nearby Cedar Island became well known nationally among sportsmen and vacationers. Visitors would take the train to Keller, where they would be picked up in these limos and driven a few miles to the hotel. (Andy Killmon collection, courtesy of the Barrier Island Center.)

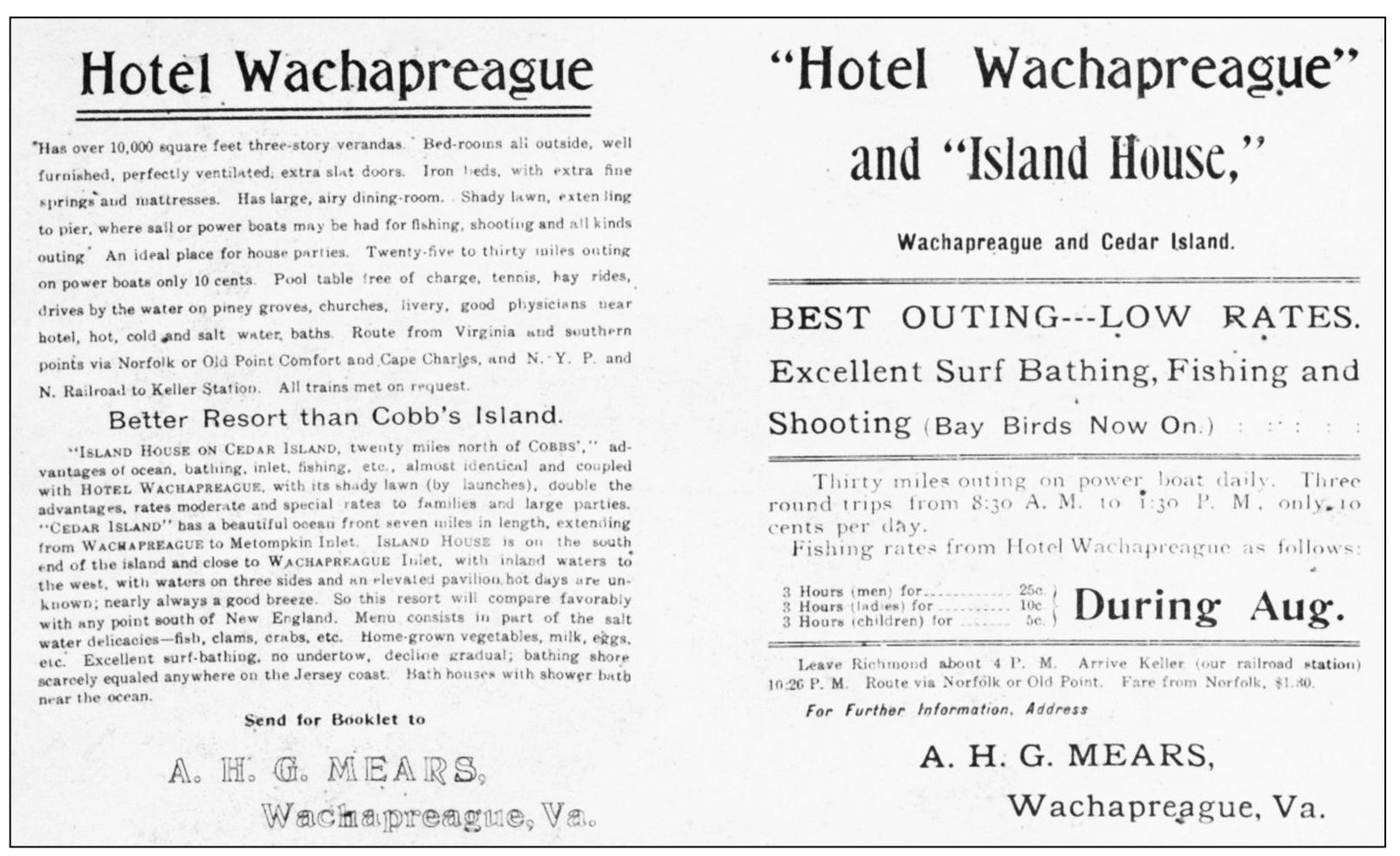

A. H. G. Mears advertised his hotel widely in sporting publications, travel journals, and newspapers, often providing exact travel instructions. This flyer, for example, points out that a train leaves Richmond at 4:00 p.m. and arrives at Keller at 10:26 p.m. Newspaper accounts of the day called Hotel Wachapreague the best-equipped country hotel in Virginia. (Andy Killmon collection, courtesy of BIC.)

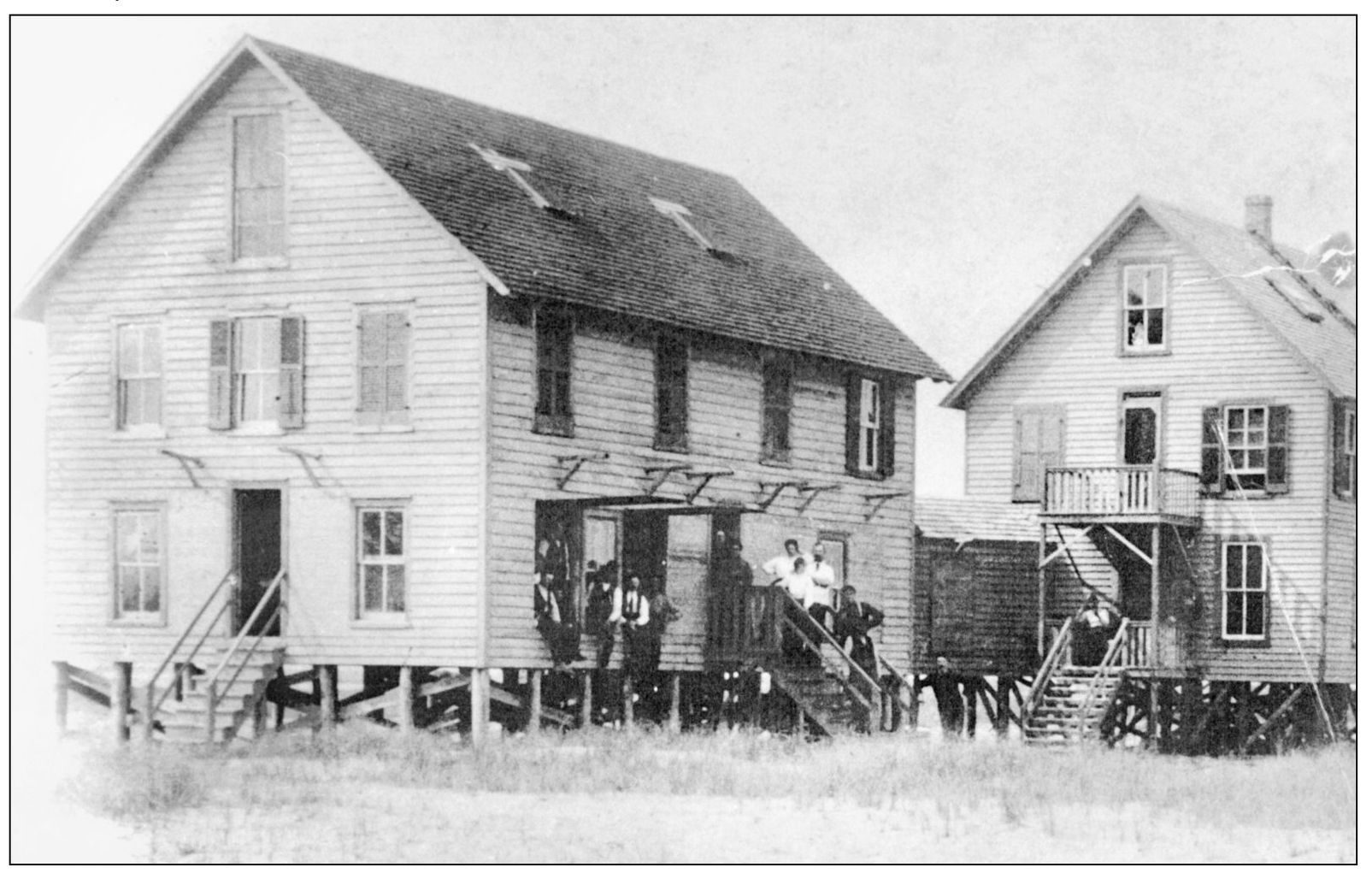

This was the Island House, sister lodge of Hotel Wachapreague. The Island House lacked some of the elegance of its mainland counterpart, but it had one significant advantage. The Atlantic Ocean was just a short walk away, so visitors who enjoyed surf bathing or fishing preferred this more spartan accommodation. (Andy Killmon collection, courtesy of the BIC.)

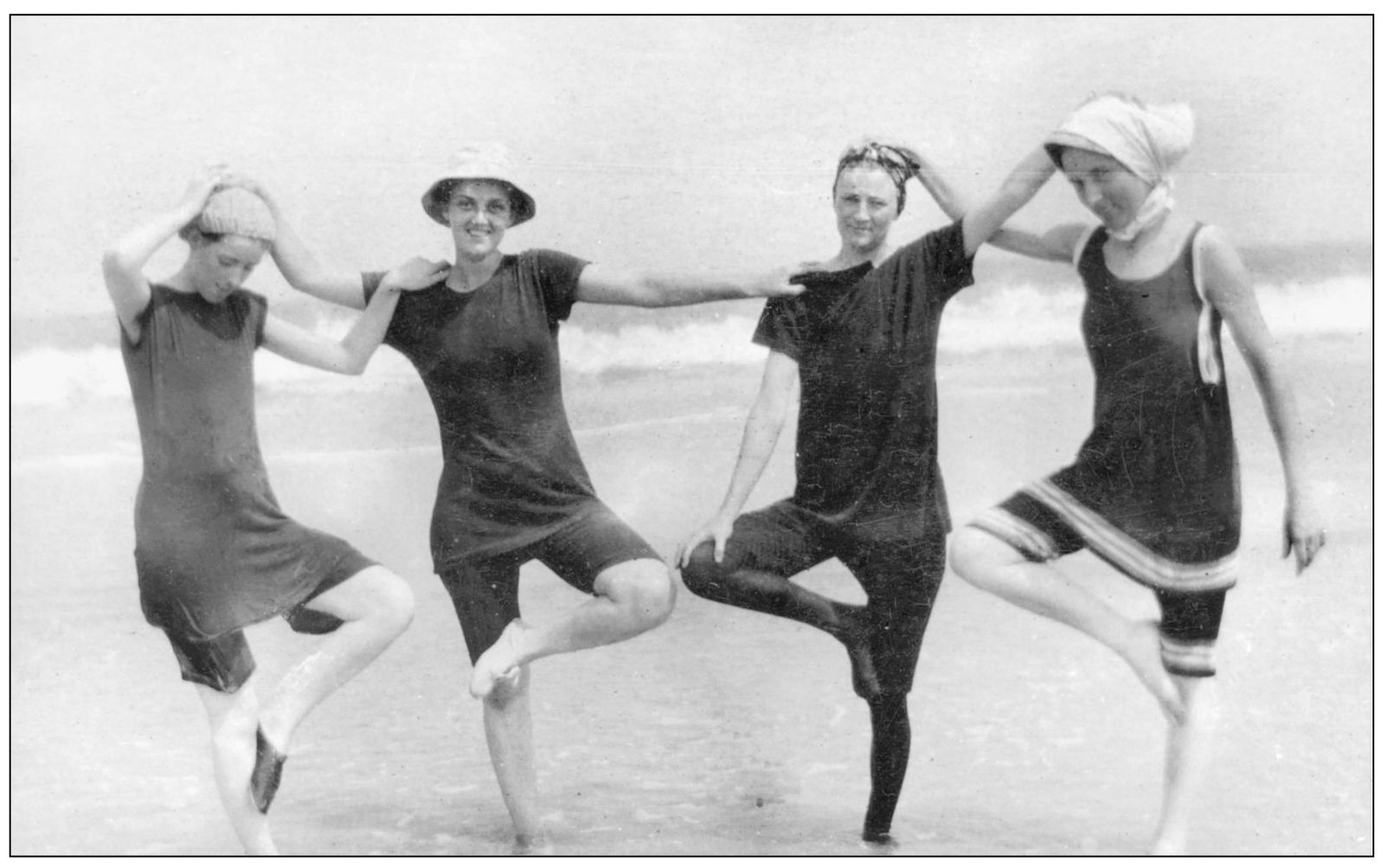

These four young people hammed it up for the camera on the beach at Cedar Island in the early 1900s. Then as now, Cedar Island was a popular destination for Sunday afternoon picnickers. People who lived in the Wachapreague area usually went to the southern end of the island. Accomac area residents took Folly Creek out to the northern end. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

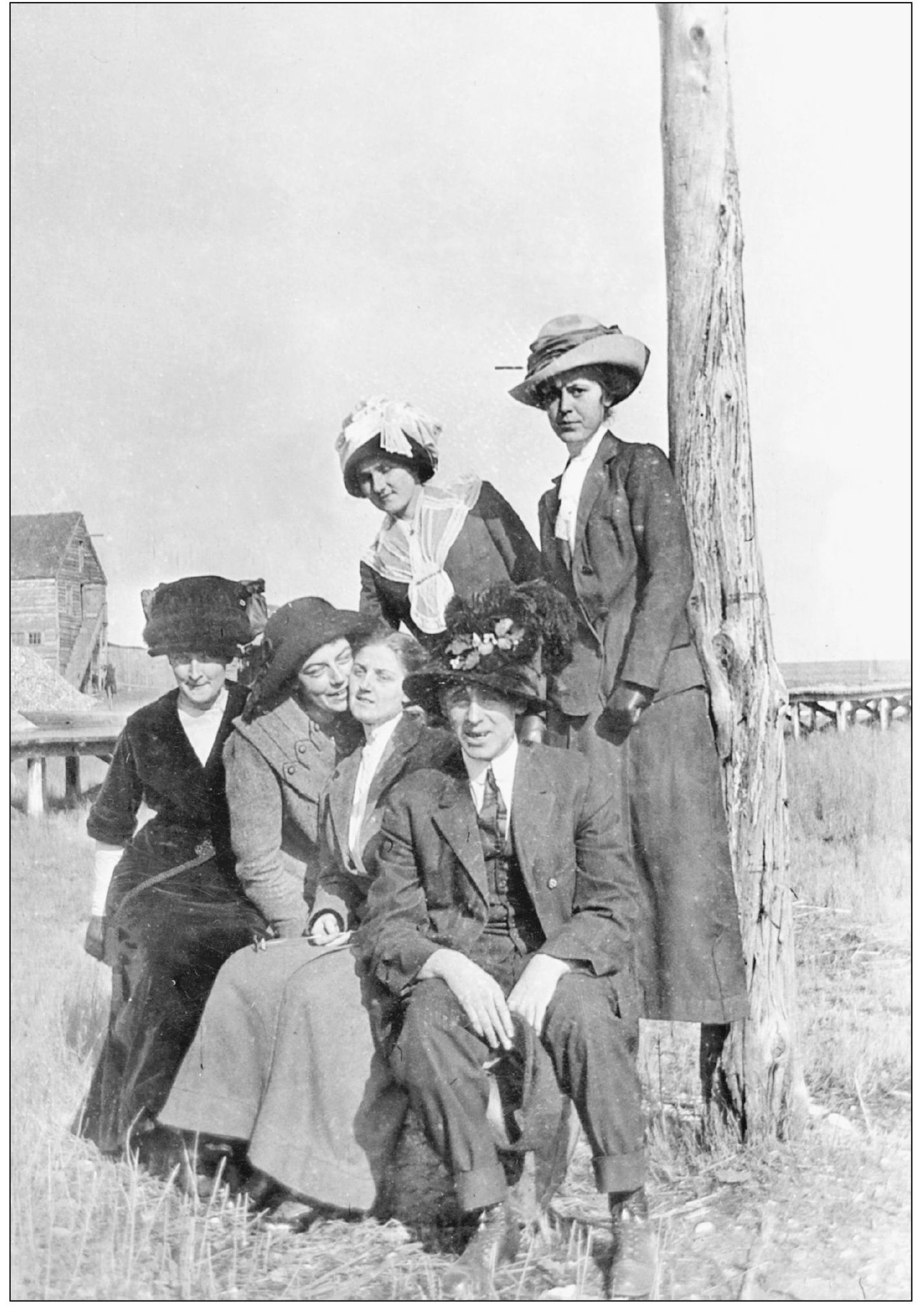

Burton’s Shore, east of Locustville, was a popular launching site around 1900, and there was a small public beach. These folks were likely heading for Cedar Island, across Burton’s Bay. In those days, Burton’s Bay was considerably deeper than it is today. It has since silted in and is no longer navigable by large boats. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

Visitors at the Island House on Cedar Island pose for the camera, the man in the foreground having borrowed a lady’s hat. The Island House can be seen on the left in the distance. Cedar Island is the only island in Accomack, other than Wallops, to have been developed. A fish guano plant operated there in the late 1800s, and more recently, lots were subdivided and sold, and a few vacation homes were built. Cedar is one of the less stable barrier beaches, however, and most of the cottages have been destroyed by storms and an encroaching sea level. Over a brief time period, the island can build up on one end and retreat on the other. Storms can open an inlet where none had been and close others. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

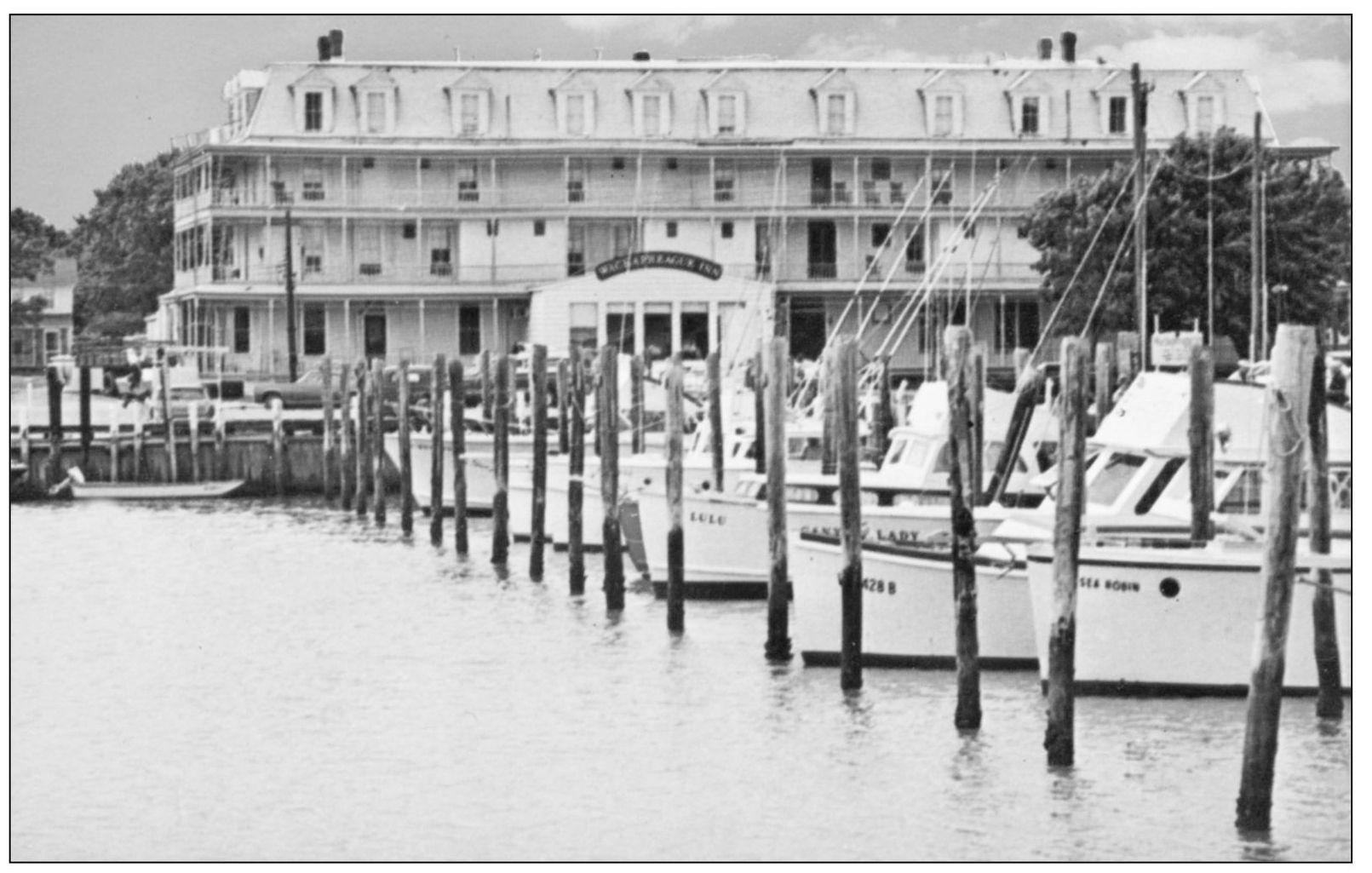

In the years following World War II, Wachapreague was a favorite destination for fishermen. Most came for inshore fishing for flounder, but offshore fishing for tuna and marlin became increasingly popular in the 1980s and 1990s. This c. 1950 photograph shows part of the fishing fleet with the Hotel Wachapreague in the background. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

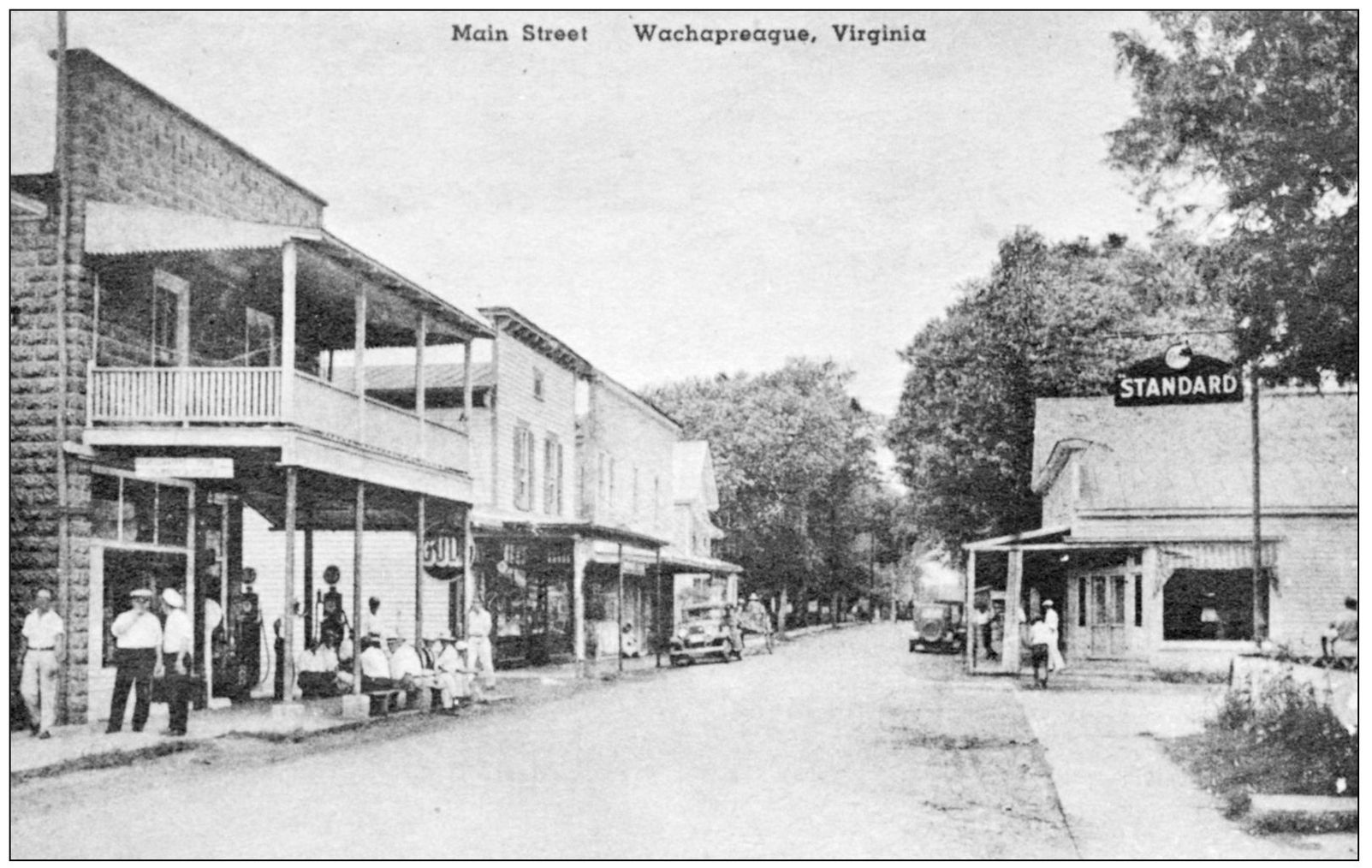

Wachapreague was not strictly a fishing community. The downtown part, shown here in the 1930s, had grocery stores, drugstores, a theater, a pool hall, and numerous other retail establishments. This part of town was significantly damaged during the storm of 1933. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

While Wachapreague was popular among sportfishermen, the economic backbone of the community centered on commercial fishing in the early to mid-1900s. This photograph shows part of the town’s commercial fishing fleet. Wharves and fish packinghouses lined the Wachapreague waterfront, and fish buyers would meet incoming boats to contract for the day’s catch. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

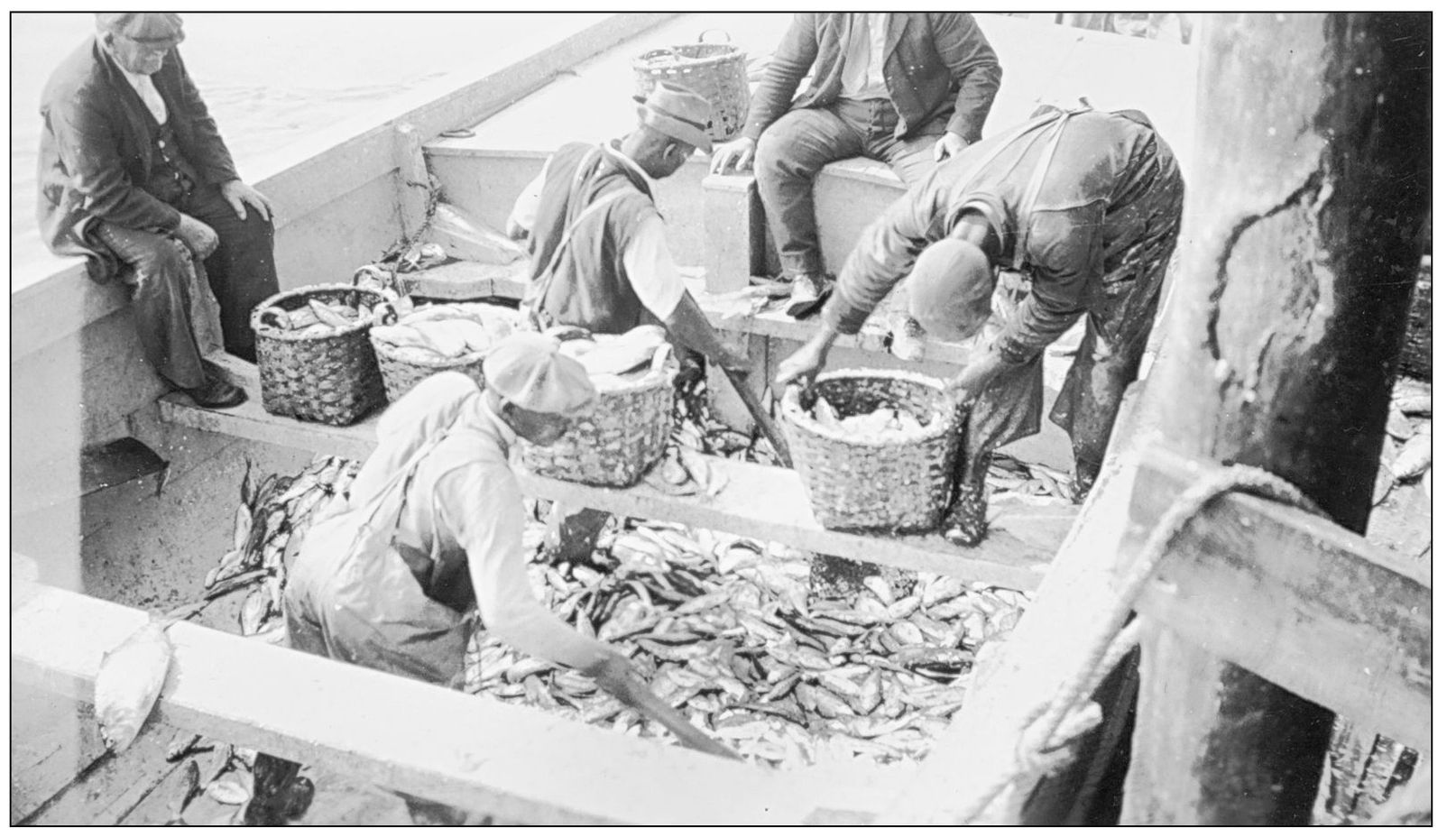

Fish were caught in pound nets, dumped into the bottom of skiffs, and then sorted and placed in baskets. Fish not sold locally were packed in ice in barrels, driven to the railroad station at Keller, and shipped to markets in Norfolk, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and other cities. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

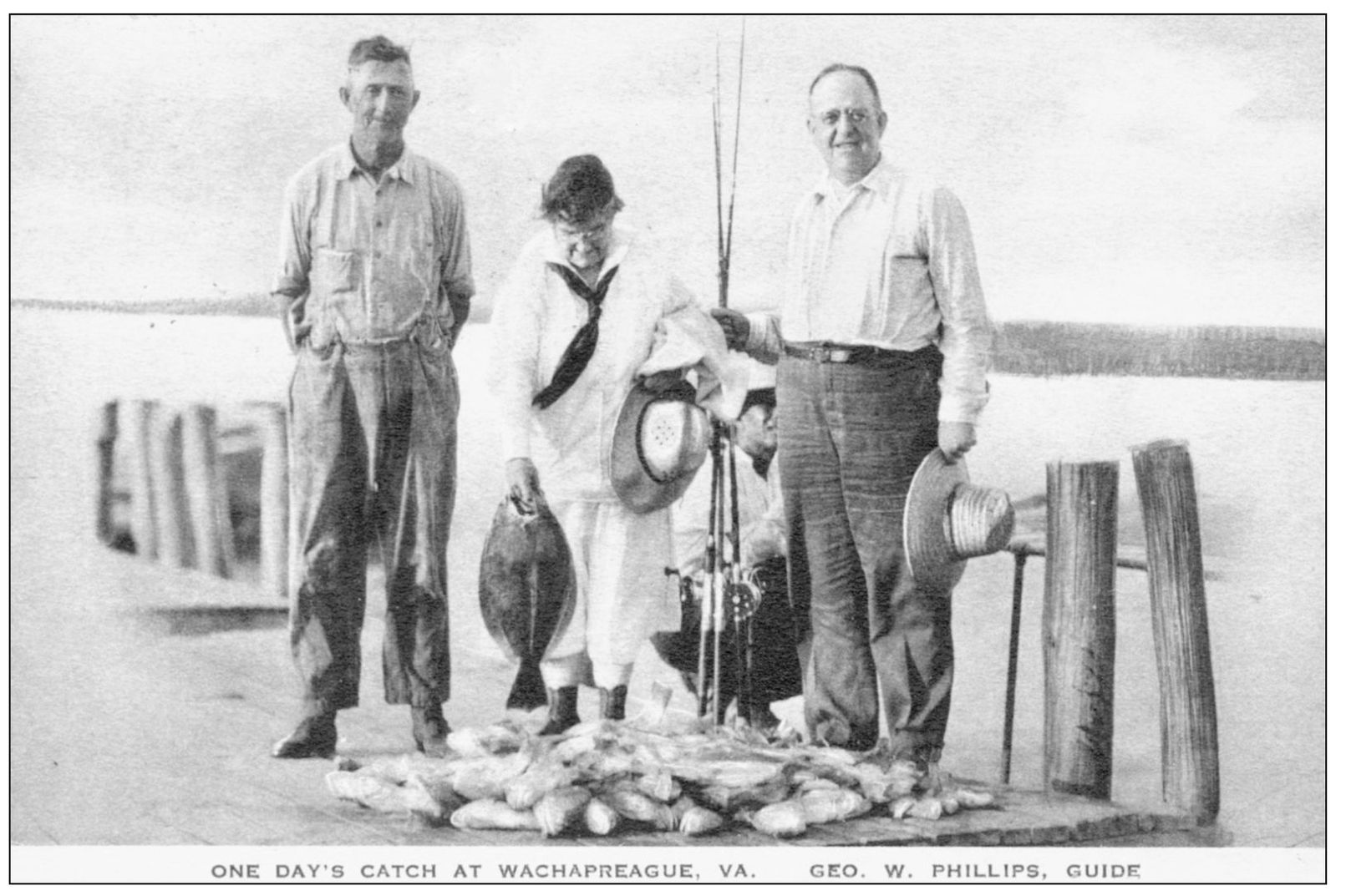

Postcards were a popular advertising medium in the 1930s. This one shows “one day’s catch, Wachapreague, Va., George W. Phillips, guide.” Phillips (left) poses with an unidentified pair of anglers who obviously had a successful day. (Courtesy of ESVHS.)

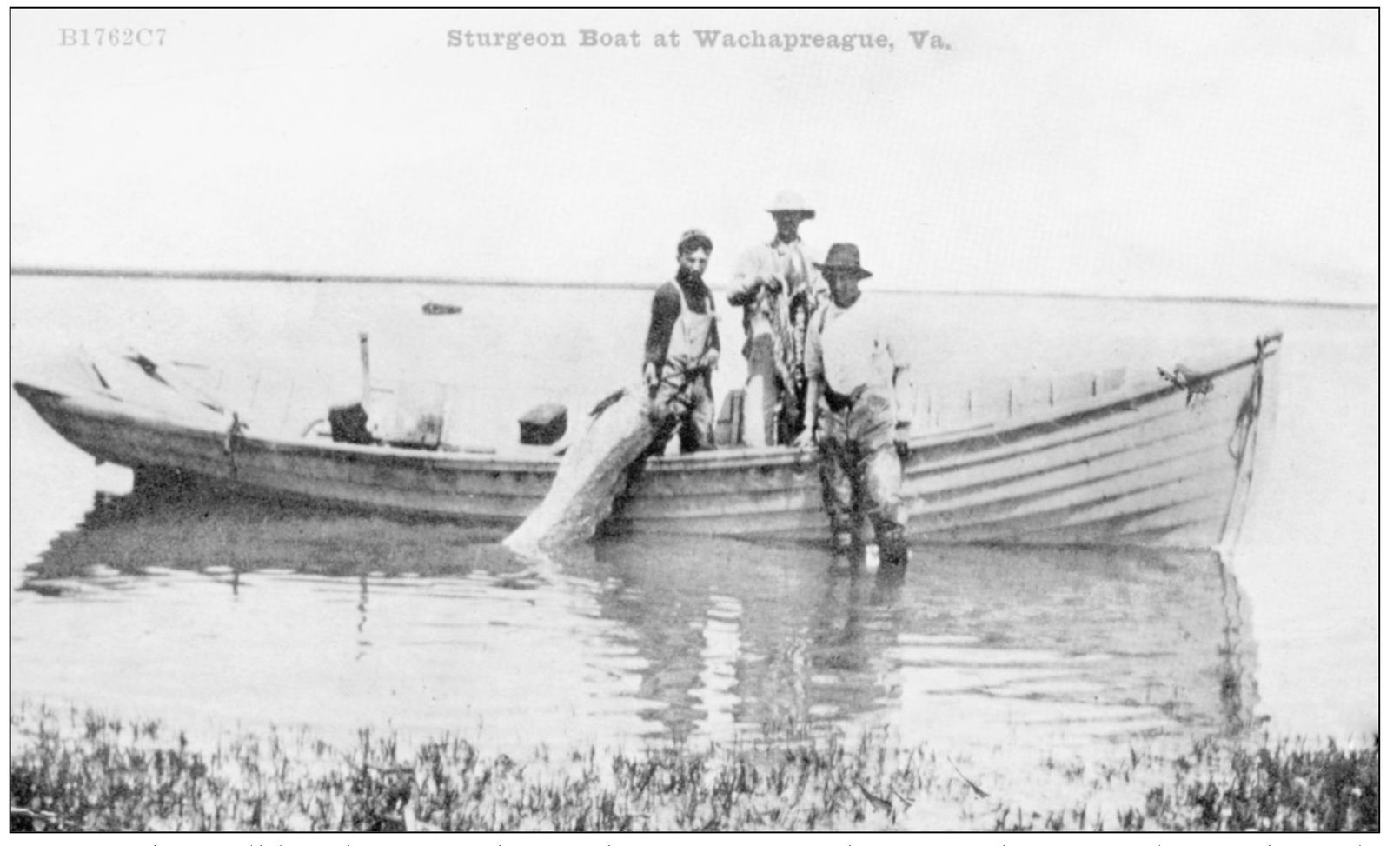

Sturgeon have all but disappeared from the waters around Accomack County, but in the early days, they helped sustain the early Jamestown colony. A 1612 account written by William Strachey told of “great shoals of herring and sturgeon and shad a yard long.” This postcard shows fishermen with a huge sturgeon supposedly taken from inshore waters near Wachapreague. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

East of Wachapreague, in the salt marsh between the town and Parramore Island, stood the Accomack Club, one of the most lavish of the private clubs established by Northern businessmen. The relationship between the club members and local residents was apparently very cordial. In the 1890s, the club sponsored a spring regatta, which was attended by some 700 local people. Prizes were awarded to the skippers of the fastest boats, and the club hosted lunch for all. (Andy Killmon collection, courtesy of BIC.)

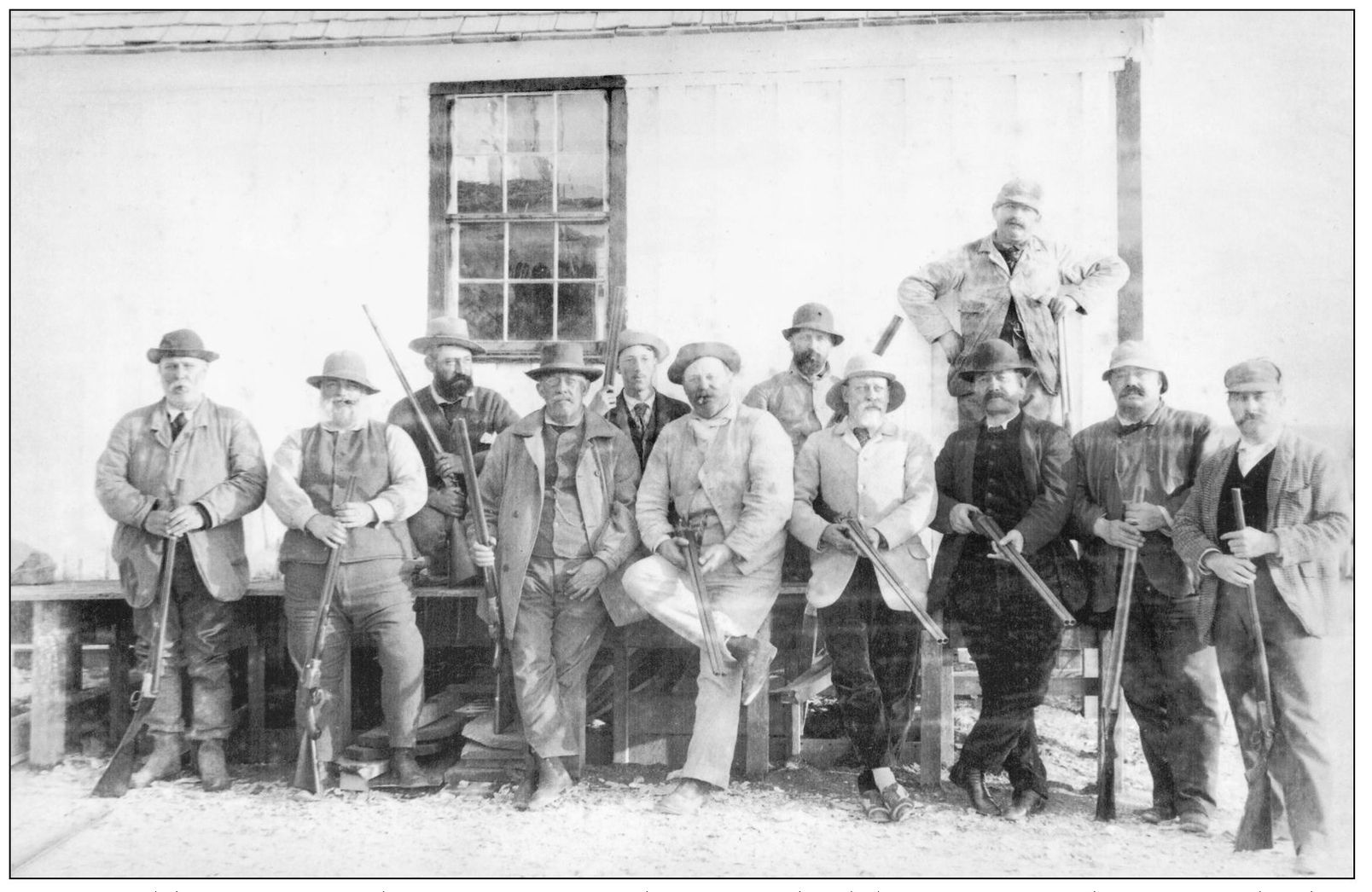

Waterfowl hunting was the prime reason these seaside clubs were formed. Business leaders entertained their clients at the clubs, and there are numerous news accounts of presidents and politicians spending time waterfowl hunting on the seaside. This photograph is believed to include Pres. Grover Cleveland, second from right. (Andy Killmon collection, courtesy of BIC.)

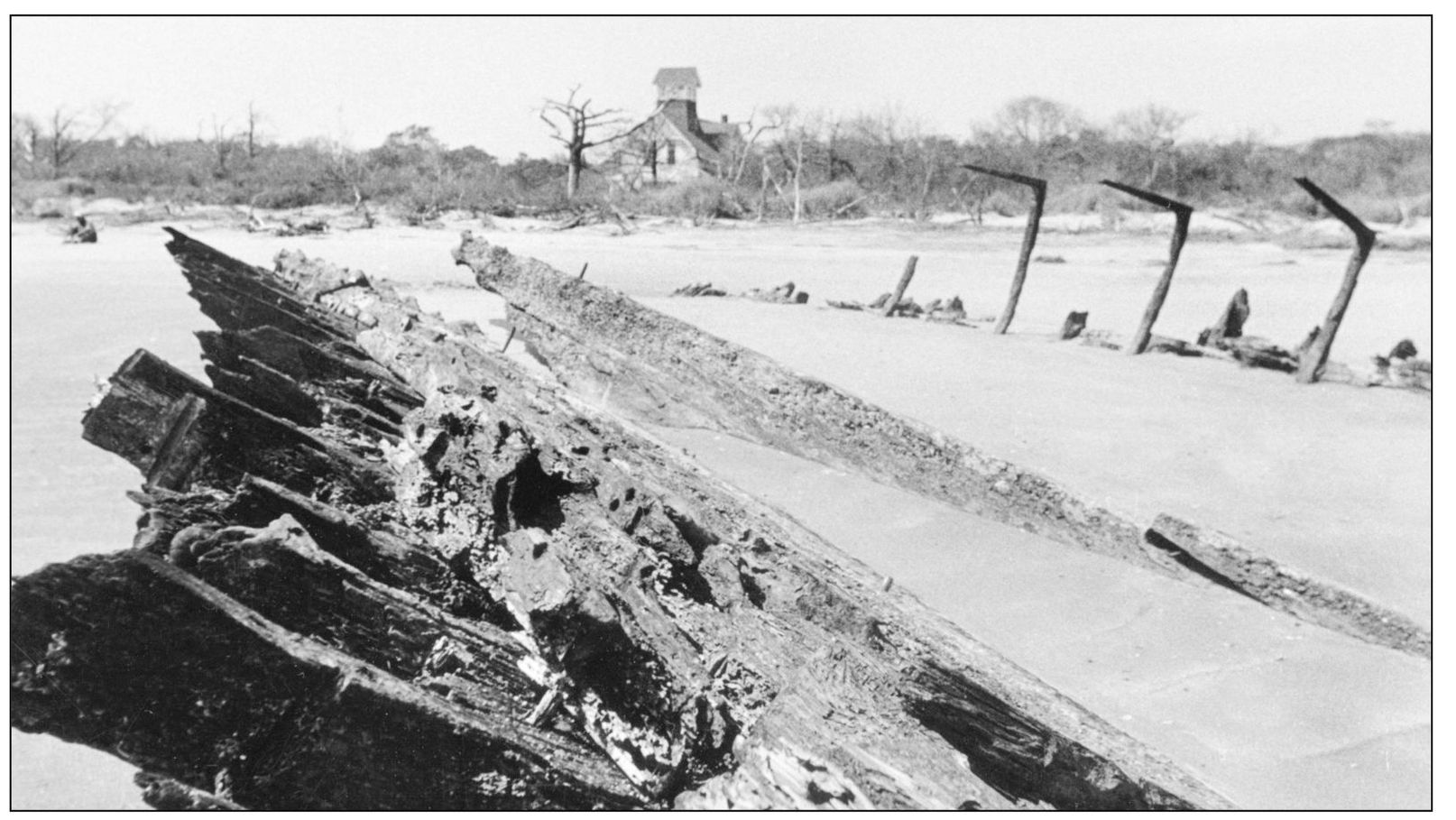

Sporting clubs were not the only buildings on the barrier islands. The U.S. Lifesaving Service had an active presence there beginning in 1874, when it authorized five stations between Assateague and Smith Island in Northampton County. This is the Parramore station, authorized in 1882. In front of the station is the wreck of the merchant ship De Braak. This station was struck by lightning and burned around 1990. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

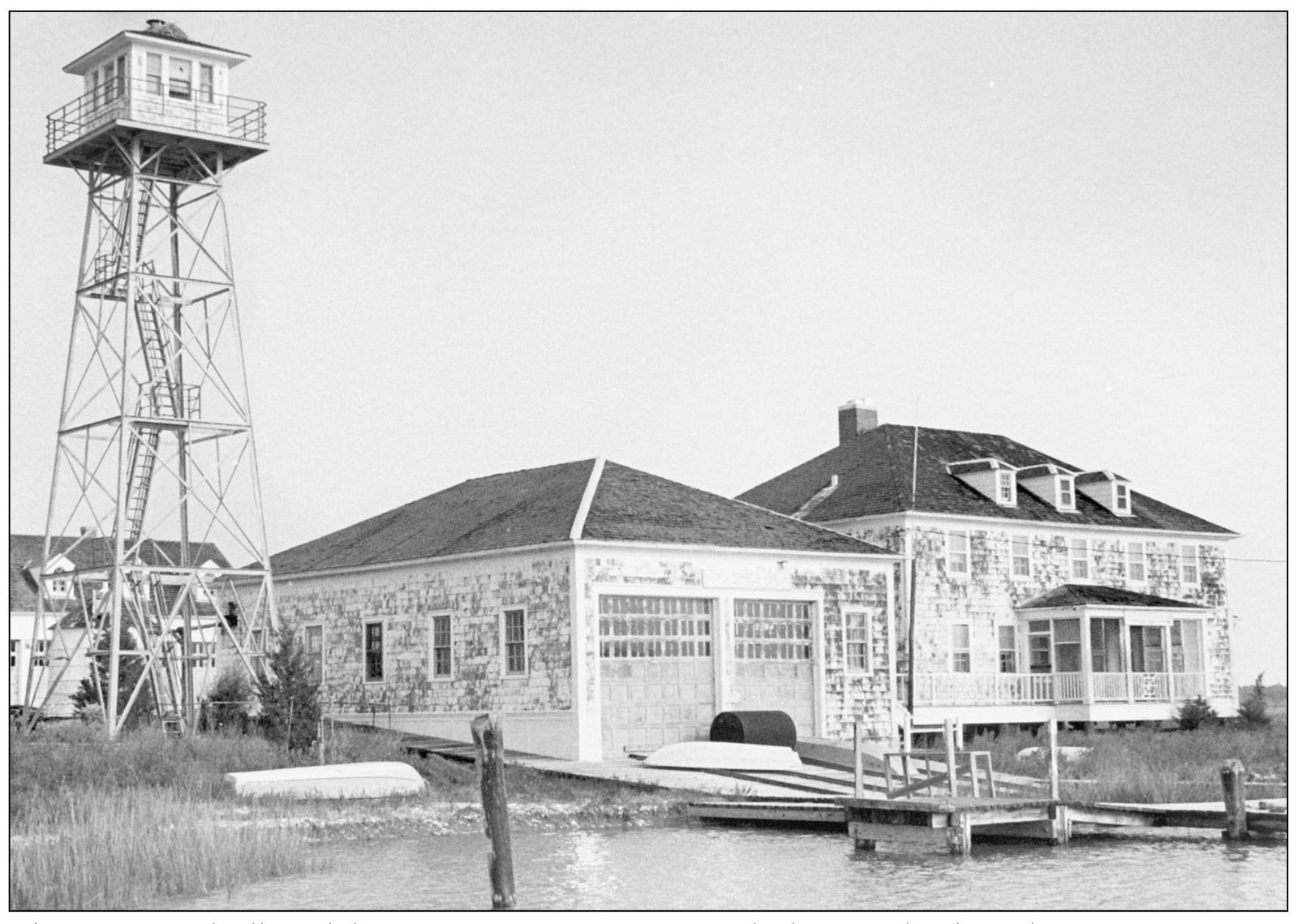

The coast guard followed the U.S. Lifesaving Service on the barrier islands, with numerous stations along the coast. This is the one on the north end of Cedar Island. The station was decommissioned in the late 1950s and is now a private clubhouse. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

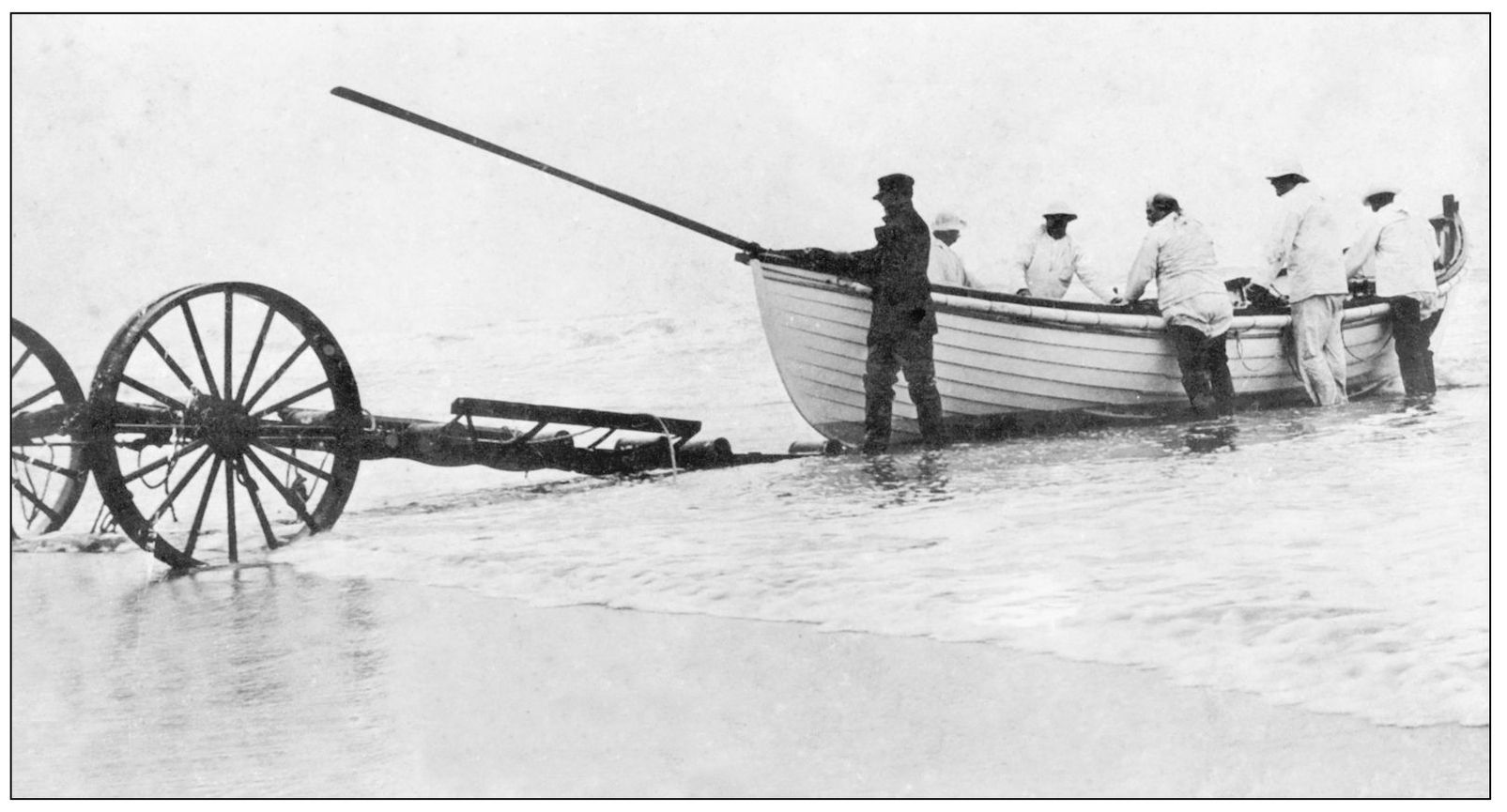

Prior to the lifesaving service, volunteers were depended upon to aid ships in distress. The service was a vital presence along the barrier beaches of Accomack, providing a level of professionalism not seen before. Each station had a keeper who was a commissioned officer, and the crew drilled on a regular basis, as seen here. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

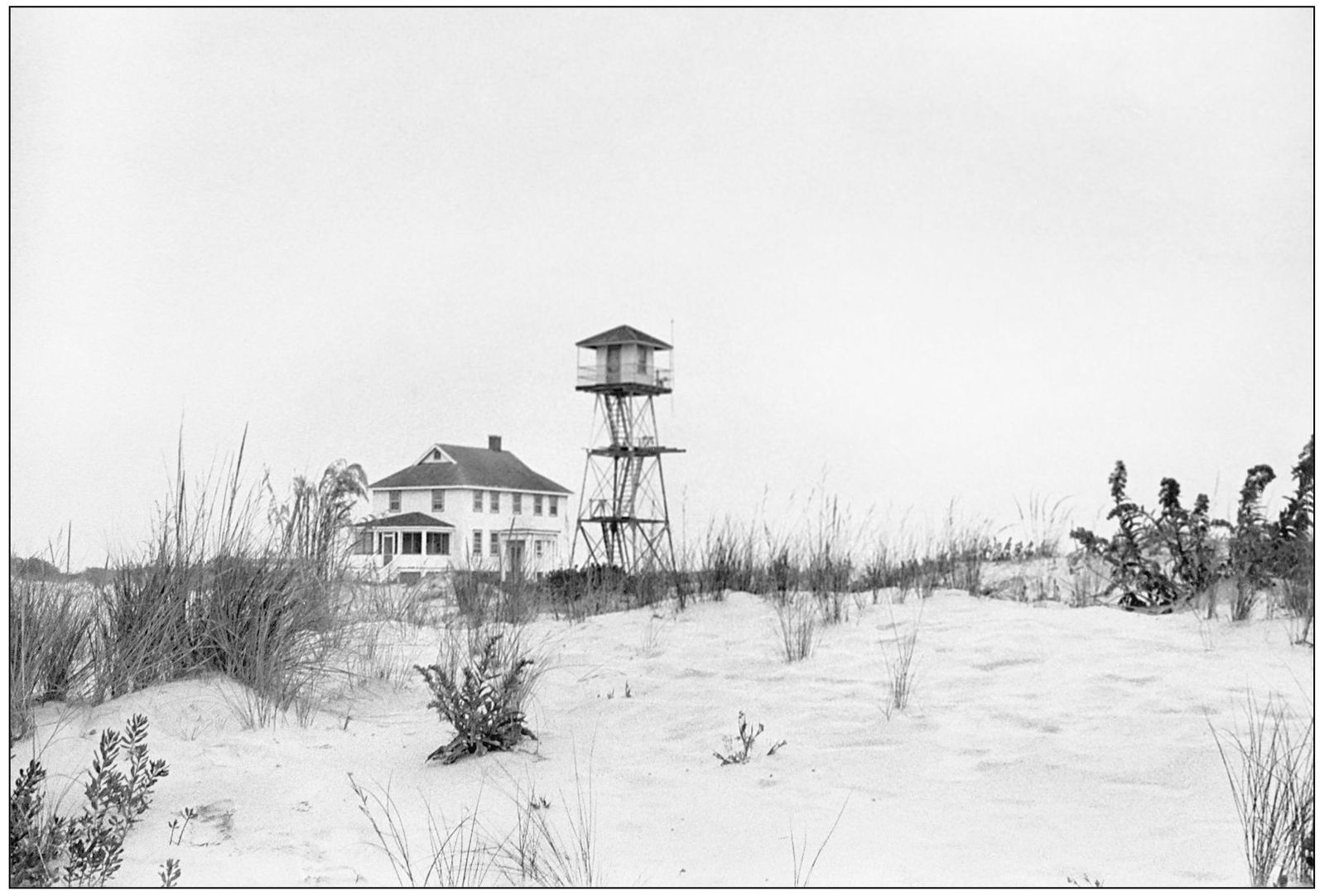

This is the station on the south end of Assateague Beach. It was decommissioned in the 1960s and is now owned by the Department of the Interior and is used by park service staff. All of the old lifesaving stations and coast guard stations on the barrier beaches have now been decommissioned, modern communications and air rescue having made them obsolete. The last station to be closed was Parramore, whose staff now works out of the town of Wachapreague. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

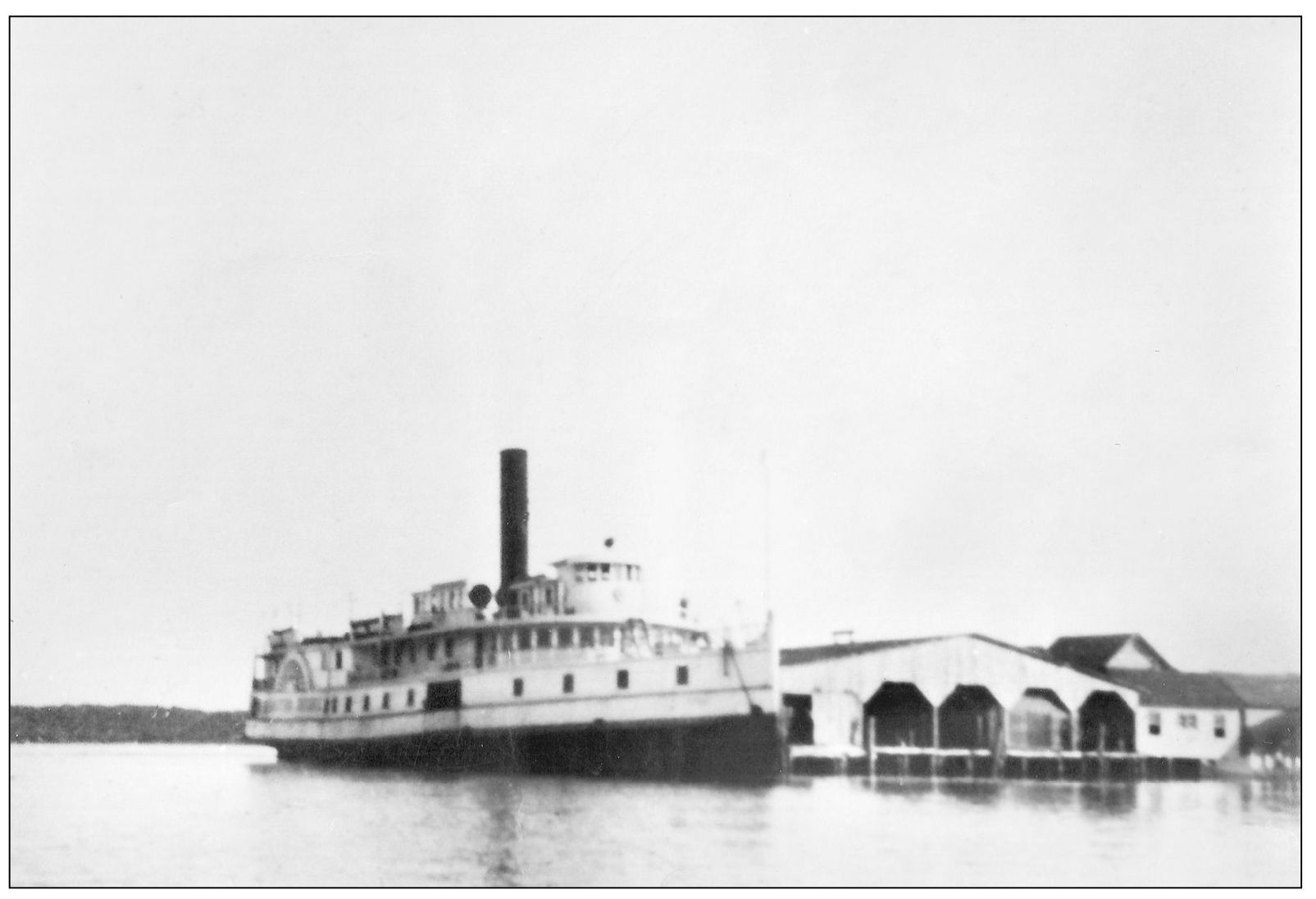

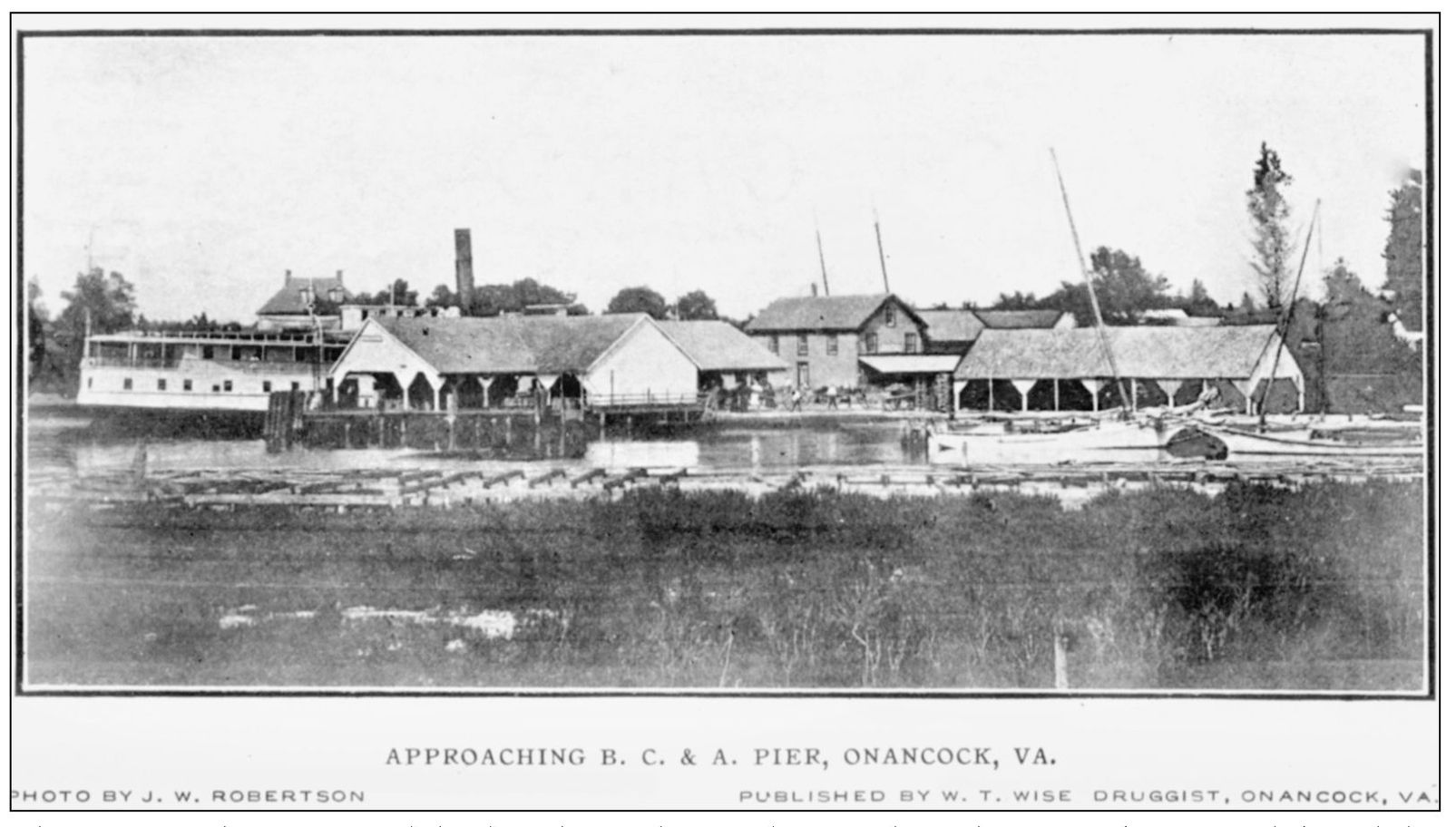

Onancock has long been Accomack’s chief link with the Chesapeake Bay and beyond. The Virginia General Assembly in 1680 passed a law requiring each county to have a town of 50 acres to serve as a port of entry, making it easier to collect taxes on items imported and exported. A site between the forks of Onancock Creek was purchased from Charles Scarburgh to be the port of entry for Accomack. The land was surveyed in 1681, and construction soon got underway on Port Scarburgh, which later became Onancock. The steamer Virginia is docked at the Baltimore,

Chesapeake, and Atlantic (BC&A) Pier in this 1927 photograph, probably loading potatoes heading for market in Baltimore. Even though the railroad opened in 1884, steamboats continued to carry a large amount of freight. The link between Onancock and Baltimore was especially popular among local passengers who wanted to spend a few days shopping in the city. (Courtesy of the Cape Charles Historical Society.)

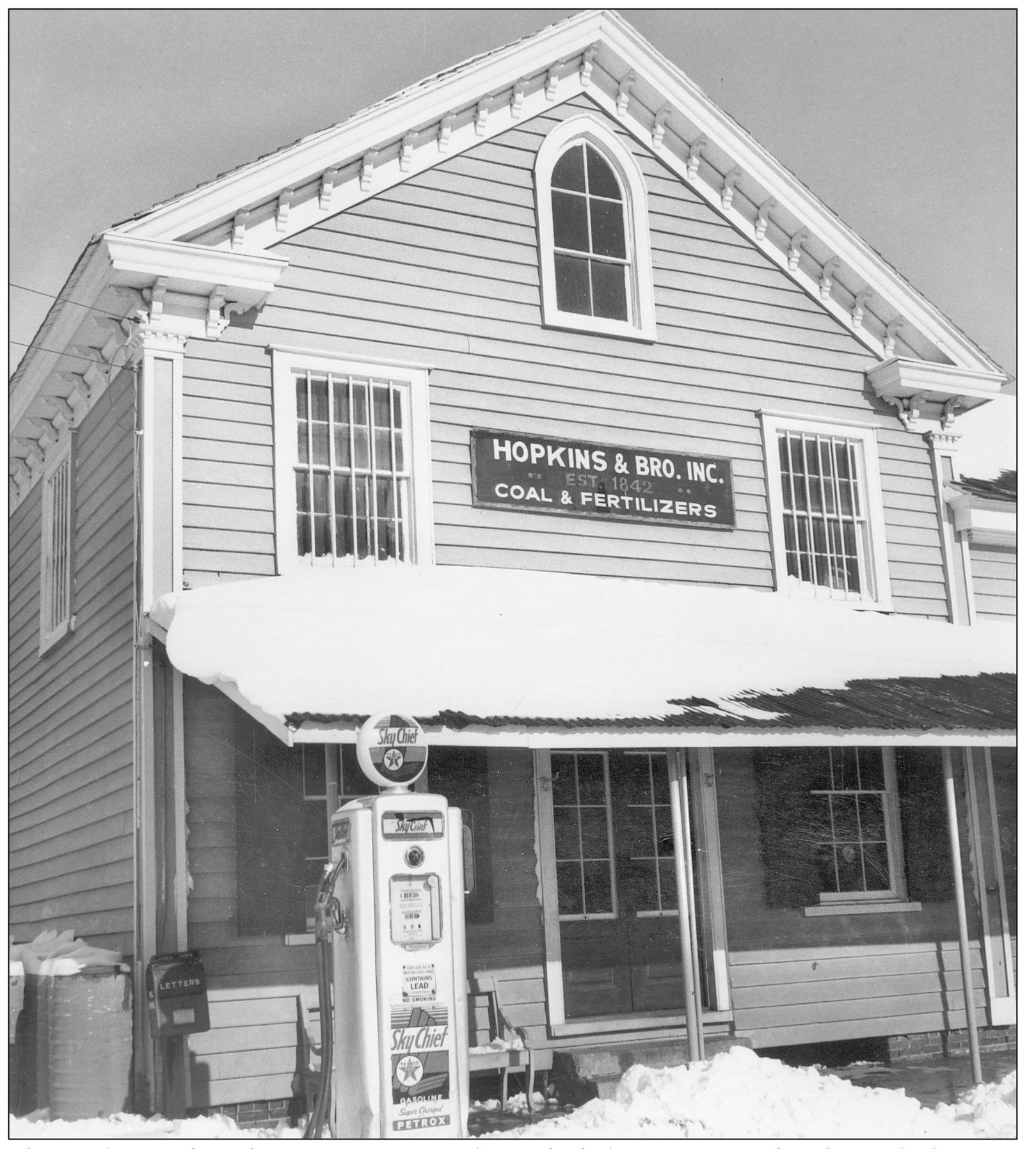

The Hopkins and Brother store in Onancock was the hub of activity at the wharf. The business began in 1842 and was in operation until the 1960s. At its peak in the late 1800s, Hopkins and Brother operated a fleet of sailing ships to import and export goods and produce. Local farmers and watermen would bring their goods to the store to have them shipped to market, and they could stock up on farm supplies and other items. The store at the time was located a short distance north of its present location. Currently it is owned by the Eastern Shore of Virginia Historical Society and is used as a restaurant. (Robertson Collection, courtesy of ESVHS.)

This snowy view of the central branch of Onancock Creek was taken in the 1950s before the wooden Ames Street bridge was replaced by a concrete structure. The area to the right is Prospect Heights, one of the residential areas of Onancock. The business district is across the bridge on the left. (Robertson Collection, courtesy of ESVHS.)

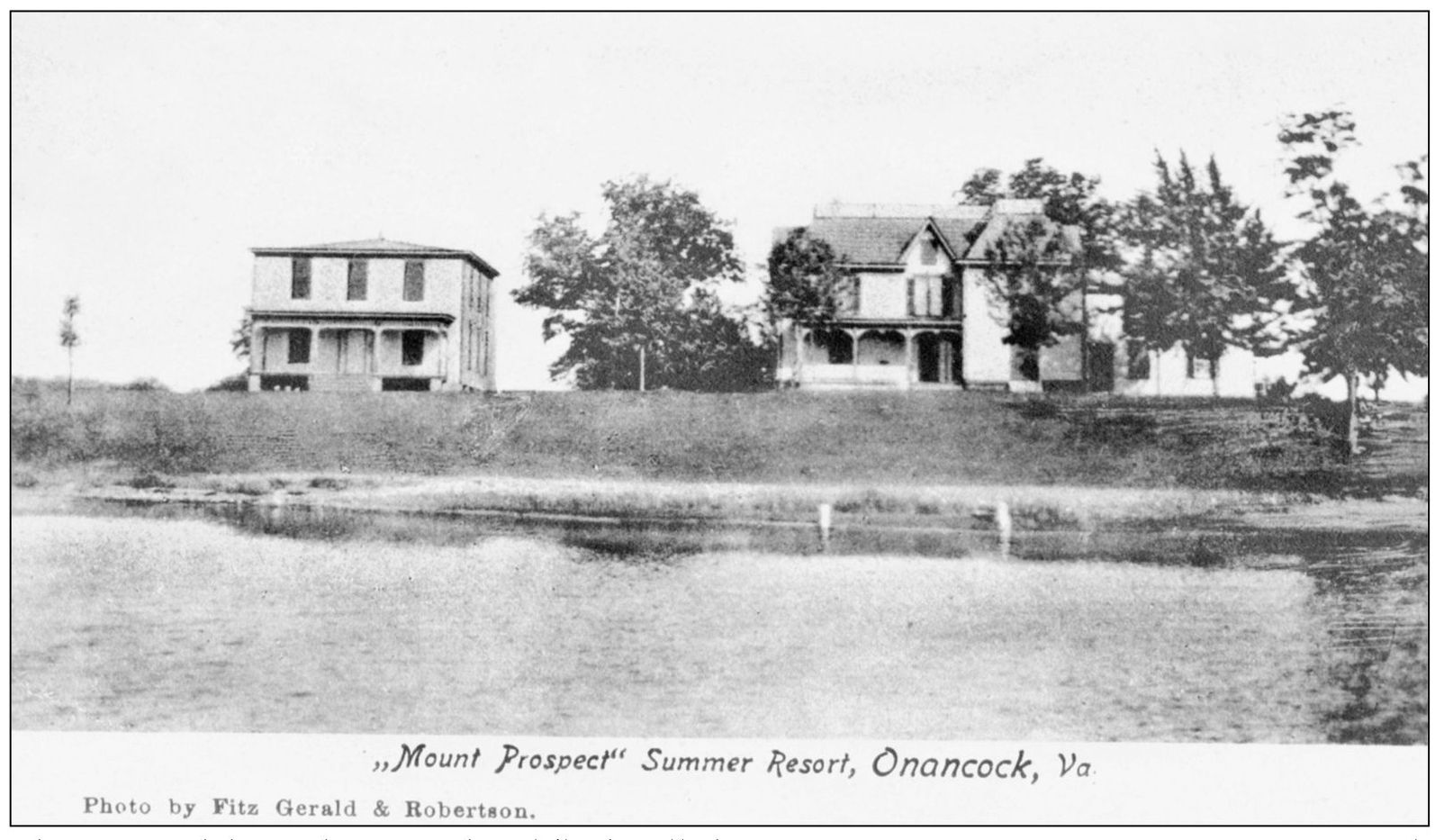

This postcard shows the square hotel (left), called Mount Prospect “Summer Resort” on Onancock Creek. This building was similar in construction to the 1887 hotel in town called the Grand Central Hotel, which was on the site of the present post office. Onancock’s hotels had a flourishing summer business in the late 1800s and early 1900s, as well as a year-round flow of traveling salesmen, or drummers. (Courtesy of the Eastern Shore Railroad Museum.)

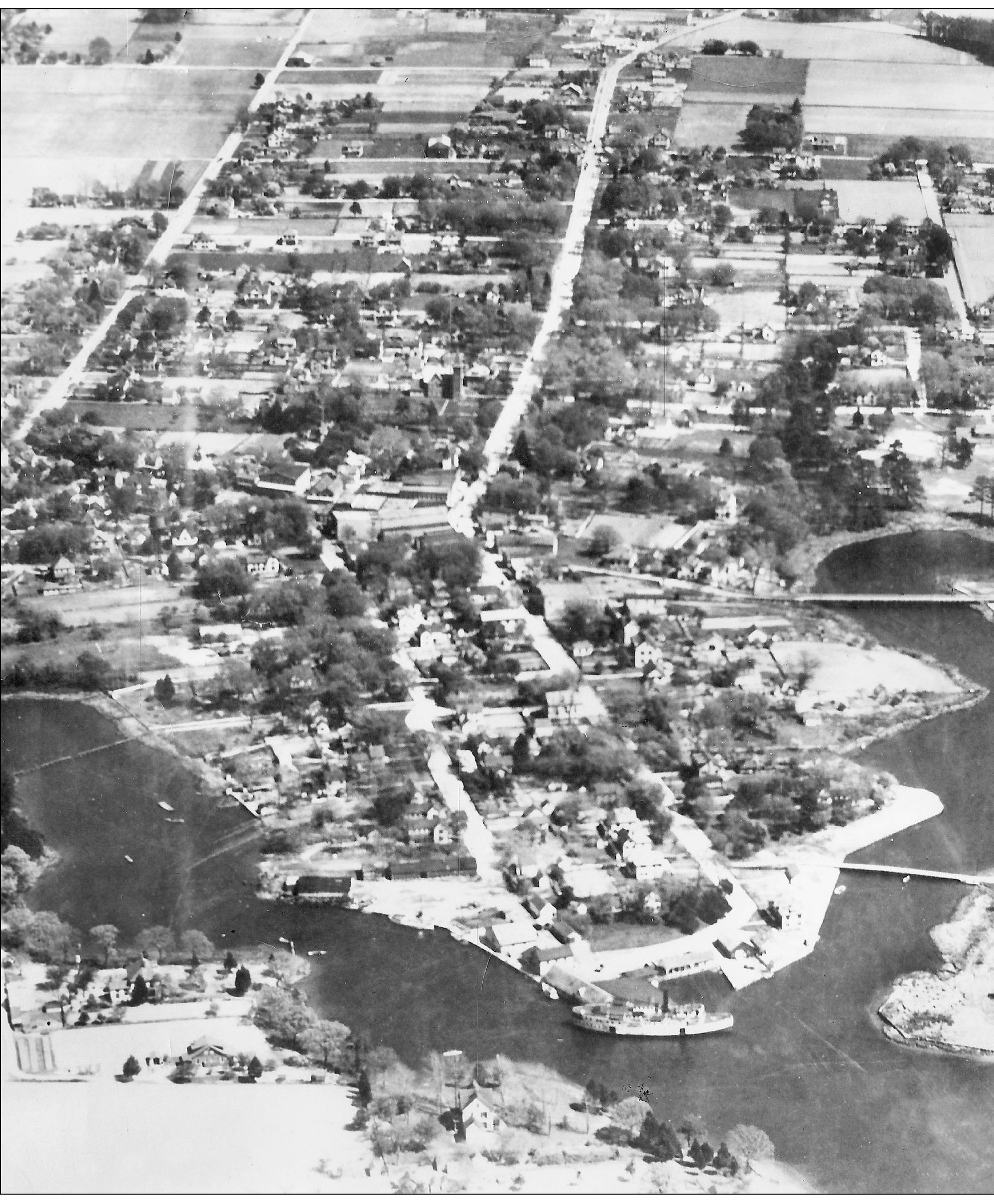

This late-1920s aerial view of the Onancock harbor shows the north and central branches of the creek, as well as the two bridges (Bagwell, bottom, and Ames) to Prospect Heights and the main streets in town. Market Street runs from the harbor through town. King Street parallels it on the left, and Kerr Street is seen in the top left portion of the photograph. The BC&A Pier is in the lower portion of the photograph, and a steamboat is docked at the west end of King Street. (A. Parker Barnes collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

This is the steamer Virginia docked at the BC&A Pier in Onancock around 1930. The Virginia was a familiar sight in waterfront towns along the bay. She ferried passengers and goods to and from the port at Baltimore and called on many communities along the way. She was built in 1901 by the William R. Trigg Company of Richmond, was 191 feet long, and was one of the fastest steamboats on the bay, clocking a speed of 18 knots in a 1902 trial. (A. Parker Barnes collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

This view of the Onancock harbor shows the Hopkins and Brother store (center right) and the covered piers where potatoes and other crops awaited shipment to market. The steamship in the background is likely the Pocomoke, which often called at Onancock. (Courtesy of ESPL.)

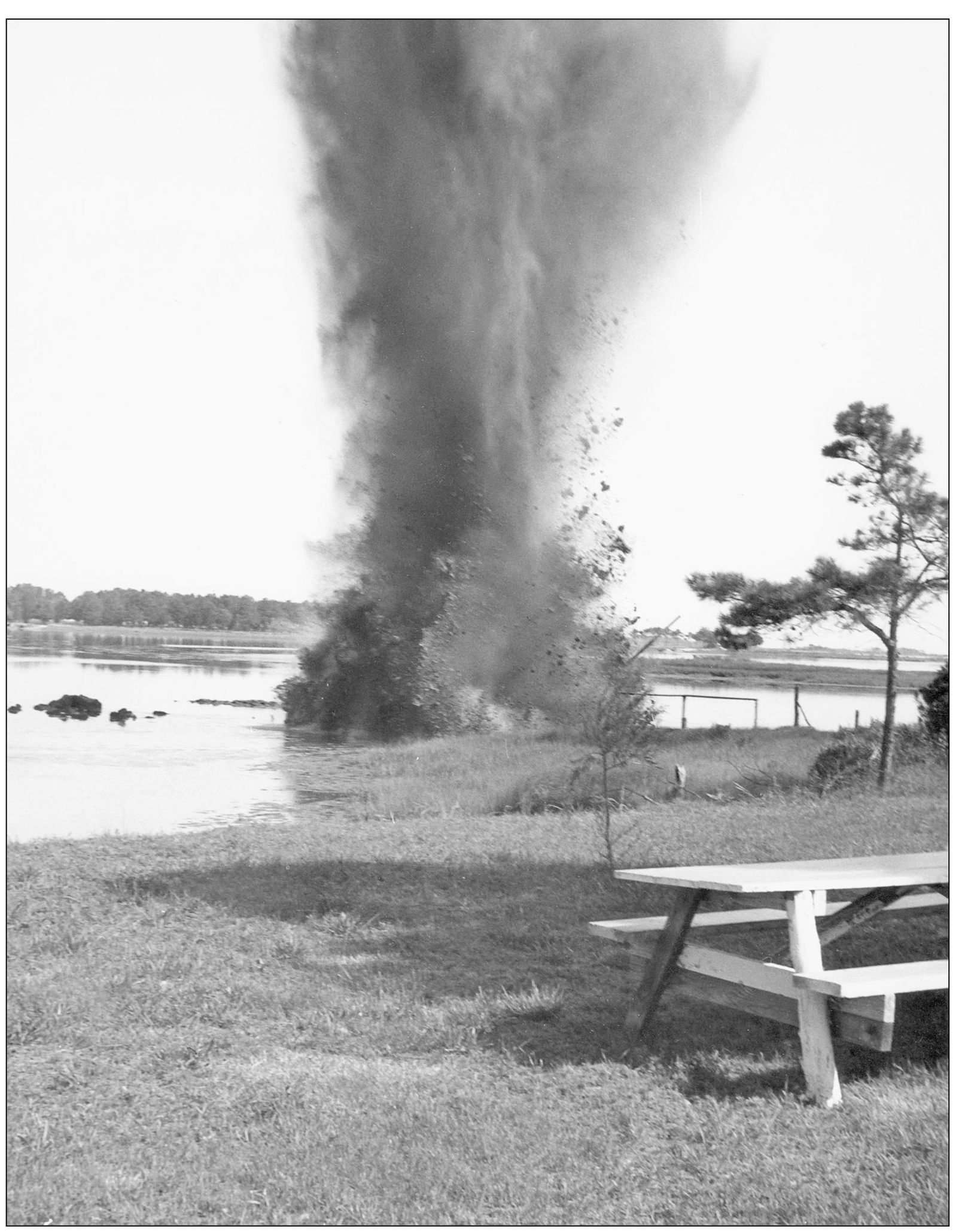

Dr. John Robertson, town physician and photographer, lived and worked on North Street in Onancock, but he had a vacation home on Onancock Creek. The waterway leading to the home was not deep enough to accommodate Dr. John’s boat, so he decided to deepen it with a charge of dynamite, and he documented the project with his camera. The blast did its intended job, but it shattered the windows of a neighboring house, and for some time, local residents referred to Dr. John as “Dr. Boom Boom.” (Robertson Collection, courtesy of ESVHS.)

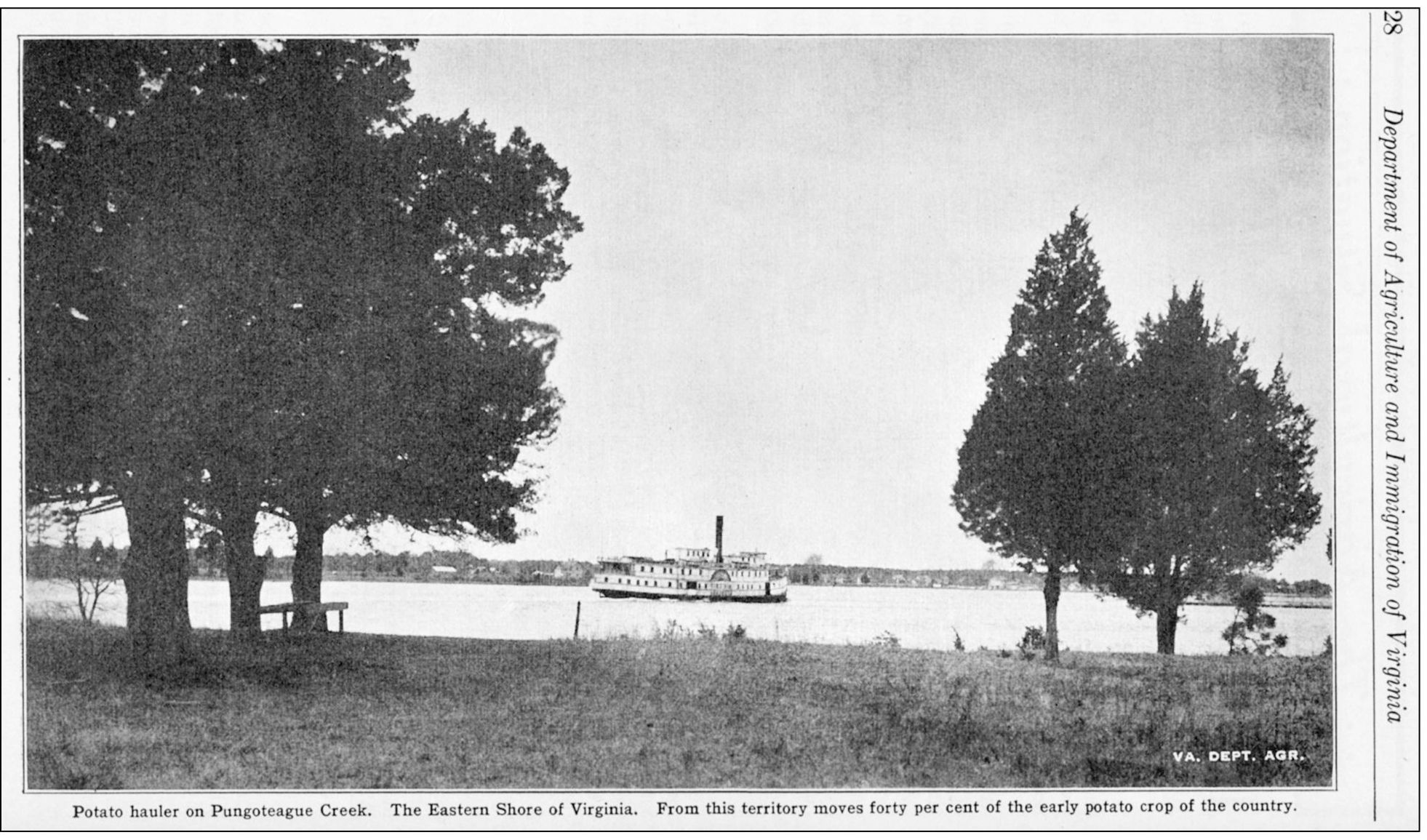

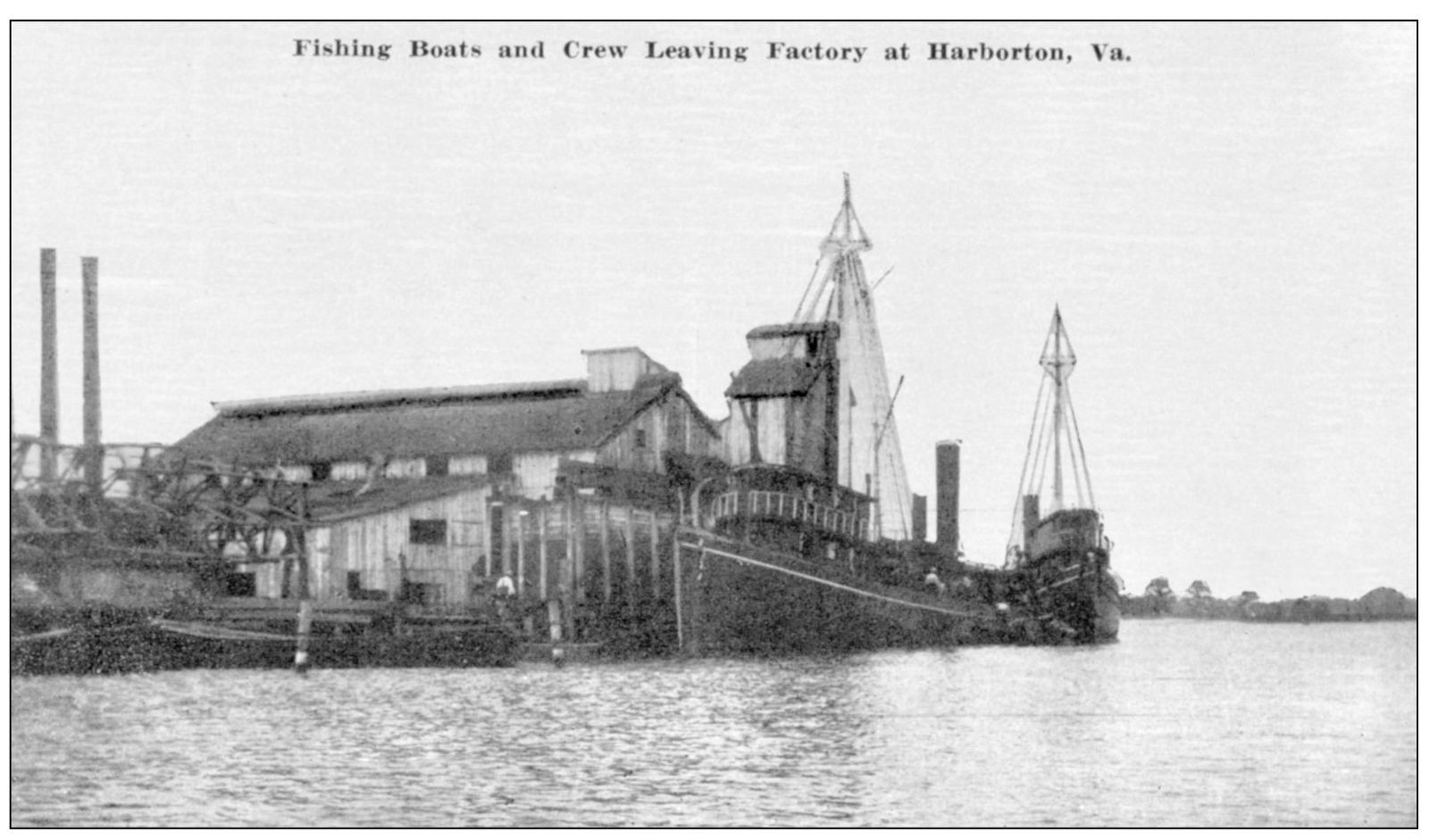

Harborton, on Pungoteague Creek, was one of the busiest waterfront communities in the county in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Hoffman’s Wharf, as it was known in those days, was one of the major shippers of potatoes, serving a large farming community in southwestern Accomack. The town had a fish processing plant that employed many people, and there was a large covered wharf flanked by numerous small shops and businesses, creating something of a water community on pilings. Here a steamship heads into port around 1920. (Courtesy of ESPL.)

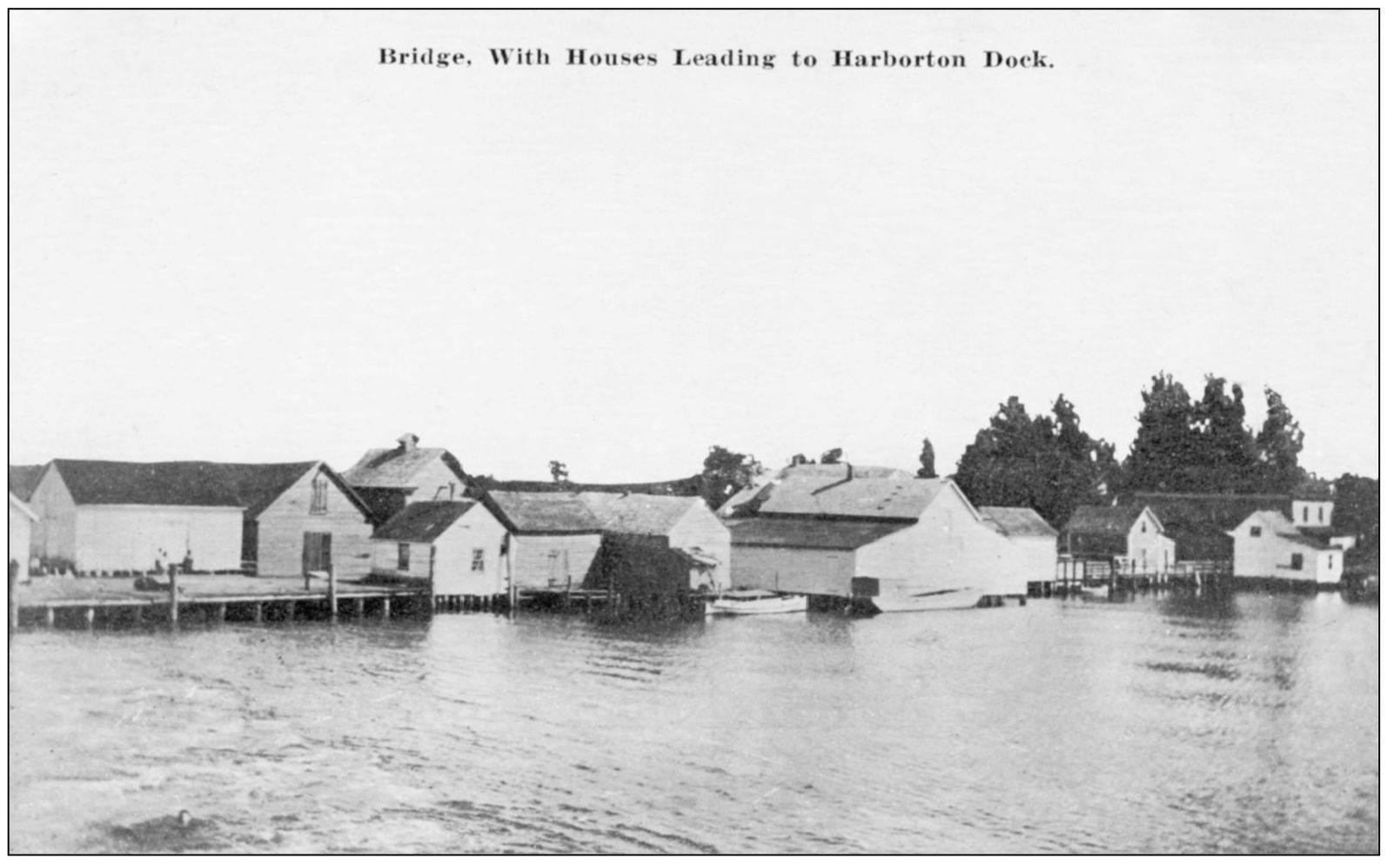

Hoffman’s Wharf at various times had a barrel factory, several fish houses, a crab house, an icehouse, a post office, mercantile stores, a bar, a grading shed and storehouse for potatoes and onions, and a waiting room for passengers. This c. 1910 postcard shows the numerous buildings that lined the carriageway leading to the warehouse at the end of the wharf. (Courtesy of Smith K. Martin IV.)

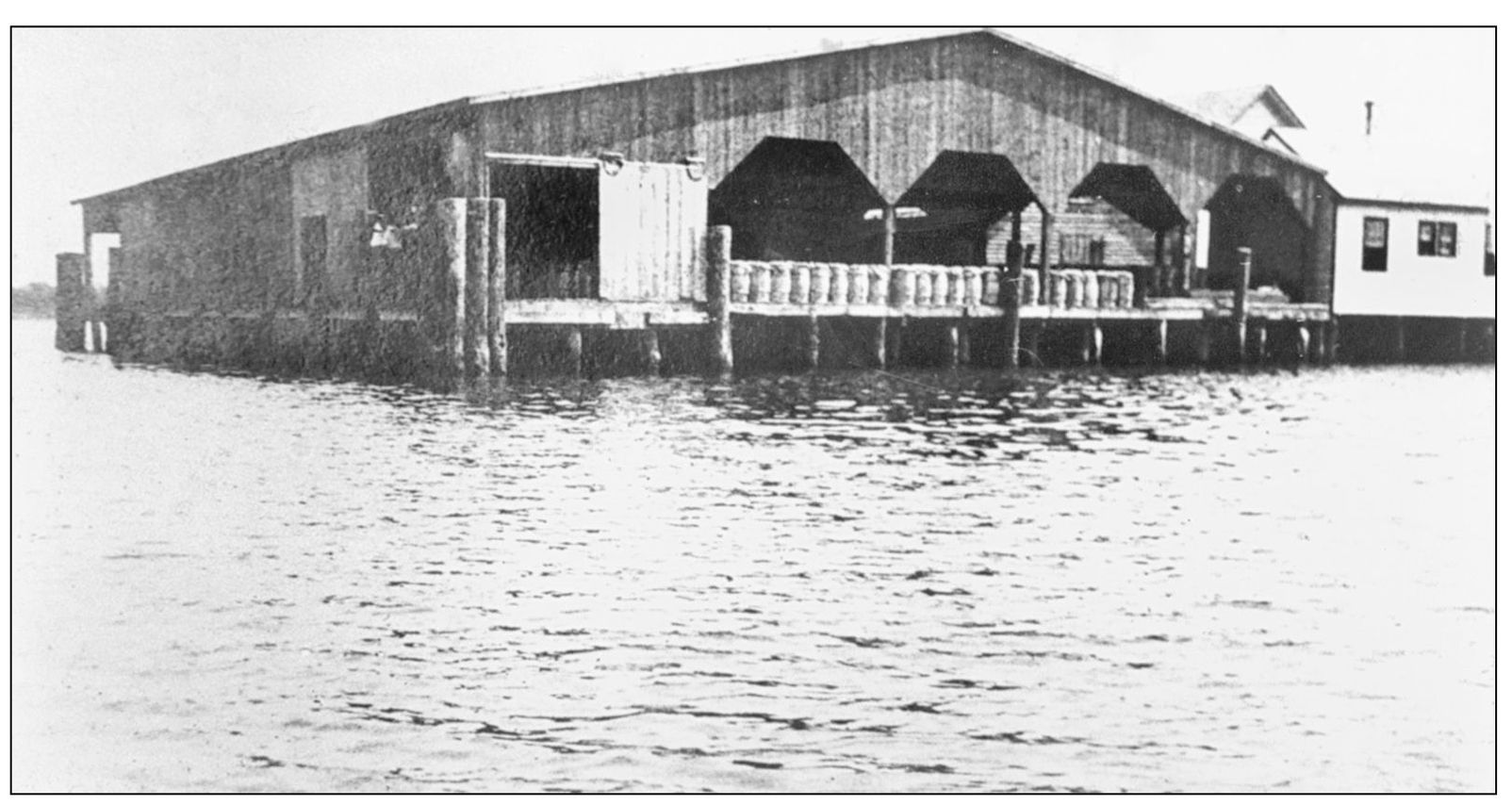

This was the warehouse at the end of Hoffman’s Wharf. Note the barrels stacked along the dock, probably filled with potatoes ready to go to market. Accomack County was one of the leading potato producers in the state. According to a July 2, 1887, news item, 350 barrels were loaded onto the steamship Eastern Shore at Hoffman’s Wharf that week, and another 600 were loaded at Bogg’s Wharf (farther up Pungoteague Creek), bringing the total number of barrels onboard from the Eastern Shore to 2,800. (Courtesy of Webster Martin.)

This photograph was taken from the covered pier at Hoffman’s Wharf. The old pier was at the location of the present one but was considerably wider, with two lanes for wagons to move goods to and from the shipping area. The wharf was originally privately owned but was purchased in March 1887 by the Eastern Shore Steamboat Company. The name Harborton was adopted in 1894. (Courtesy of Webster Martin.)

For a few years in the 1930s, a ferry ran between Harborton and Deltaville, allowing local residents to reach Richmond in about 4½ hours. The service began in 1933 with boats leaving and arriving three times a day. This is the ferry Chelsea docked at the old fish factory pier a short distance west of the main wharf. (Courtesy of Webster Martin.)

The fish plant, founded by the Powell, Morse Company, was on a point near the present boat ramp, where a barge dock is located today. In its heyday, the plant was one of the top processors in the East, sending vessels as far as the Maine coast to catch fish to process as fertilizer. The June 28, 1883, issue of the Peninsula Enterprise reported that the plant was handling a million or more fish a week, manufacturing fertilizers called Virginius Guano and Virginius Ocean. (Courtesy of Webster Martin.)

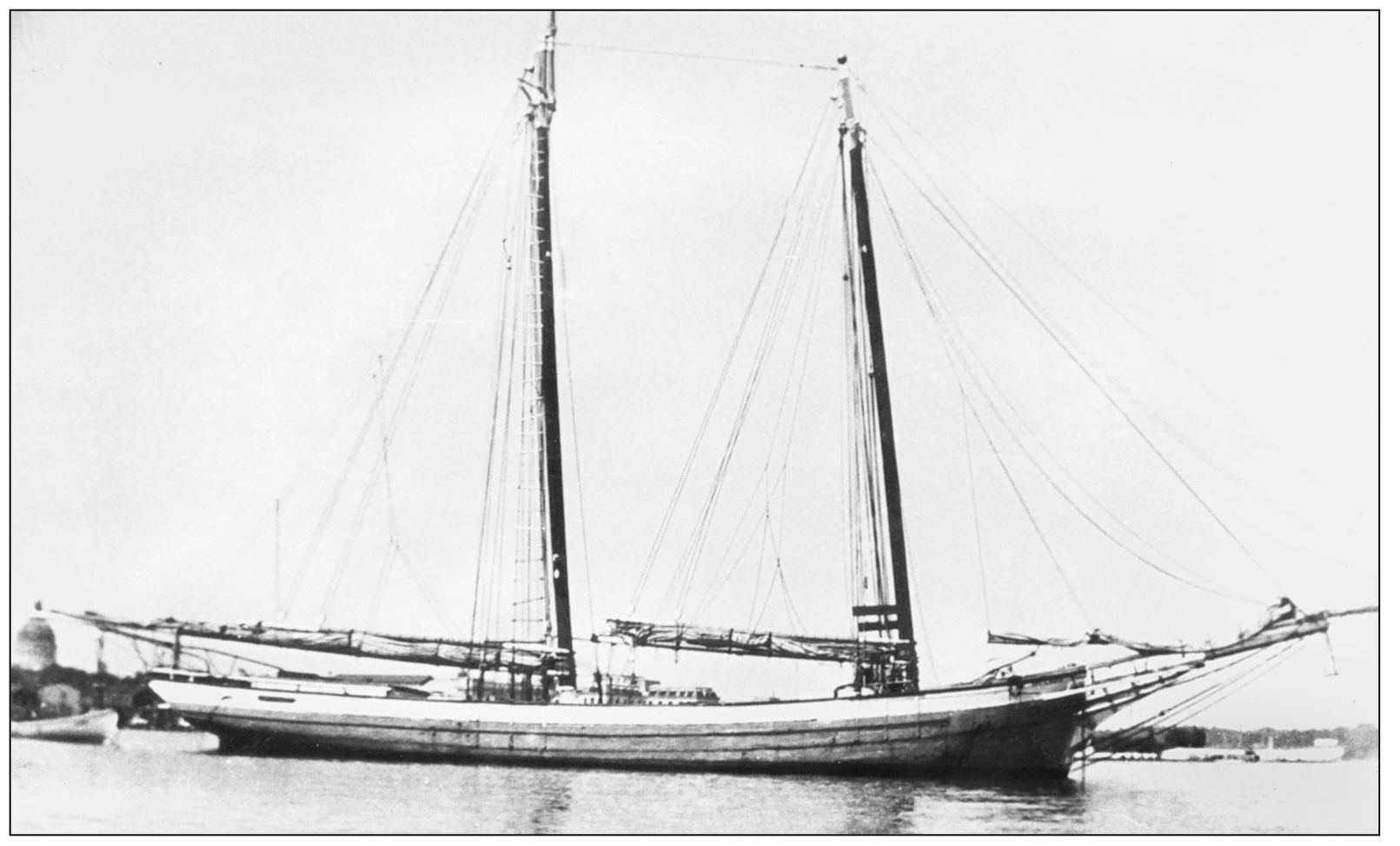

One of the biggest businesses in Hoffman’s Wharf during the steamship era was the Martin and Mason Company, which operated a lumber mill and sold a wide variety of building supplies. The store still stands and is a private residence at the waterfront. This is the schooner Smith K. Martin, built in Pocomoke City in 1899 and mainly used to ship lumber to market by the Martin and Mason Company. (Courtesy of Webster Martin.)

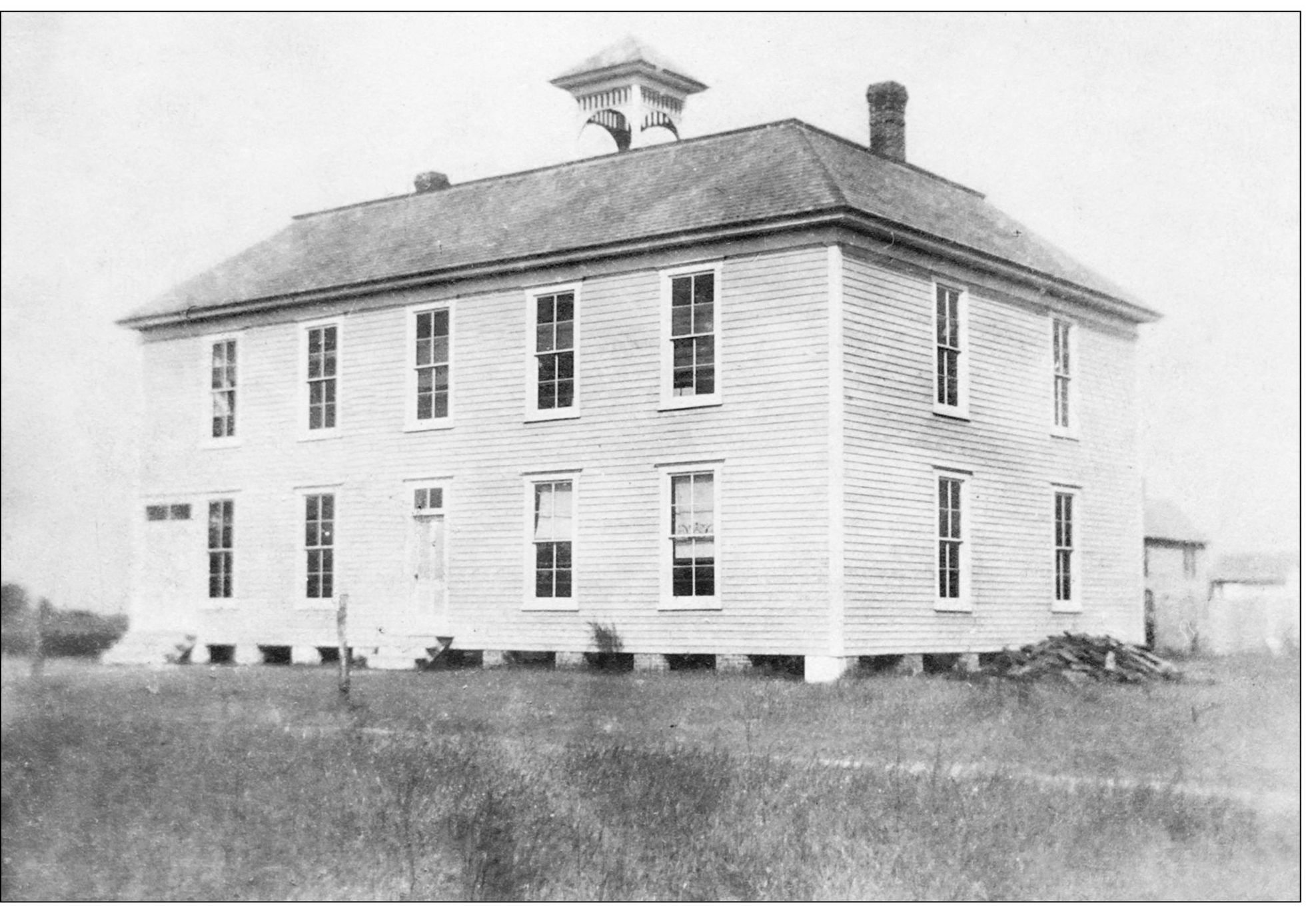

The Harborton School was on the corner where the post office is today. The first floor of the building had classrooms, while the upstairs was a meeting room for a fraternal lodge called the Junior Order of United American Mechanics. The association between the fraternal order and the school was symbiotic. One of the tenets of the Junior Order was the education of young people through a strong public school system. It was founded in 1853 in Philadelphia and claims to be the oldest fraternal order created in the United States still to exist. The term “mechanic” in this case implies artisanship rather than an ability to work on motor vehicles. (Courtesy of Smith K. Martin IV.)