Two

LIVING ON THE LAND

From the time of the first European settlements in the early 1600s, Accomack County’s principal industry has been agriculture. New settlers were granted large tracts of land, which were cleared to make room for crops. The soil was sandy, well-drained, fertile, and capable of producing good yields.

The amount of land under cultivation grew quickly through the 17th and 18th centuries, and the court town of Accomac, the center of local government, became a popular hub, a place not only to conduct legal business, but also to catch up on the news and to visit with neighbors. (Note that the county of Accomack is spelled with a “k.” The town of Accomac is not.)

The great revolution in agriculture in Accomack was brought about by the opening of the railroad in 1884. Suddenly farmers had a way of getting crops to market in a timely fashion, and the network of rails throughout the East opened up great new markets for vegetables and other crops. The railroad also had the unintended consequence of uniting farmers, who heretofore had been a rather independent lot. In 1899, a well-organized marketing association was formed that would become a national model of a farmers’ cooperative. The Eastern Shore of Virginia Produce Exchange was chartered by the Virginia legislature in 1900, and for some 50 years, it promoted and marketed local produce all over the United States and into Canada. The exchange not only marketed produce, but it also set standards for quality and consistency, realizing that a high-quality product brought premium prices.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Accomack was consistently among the top potato producers in the state. After World War II, grain crops gained popularity as modern planting and harvesting equipment was developed. And strawberry fields dotted the landscape until the 1960s, when rising labor costs made berries unprofitable.

For some 400 years, the fertile soils of Accomack County have sustained an industry that is vital to all—the production of food. The crops have changed over the years, as have the methods used to ship them, but Accomack continues to be one of the most important and prolific food producers in the state.

White potato and sweet potato crops drove the agricultural economy in the 1920s and 1930s in Accomack, but strawberries provided a nice springtime supplement. More than 1,000 acres were planted in 1920, providing income for growers and part-time job opportunities for pickers. This scene is the Belote farm near Onley in May 1927. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

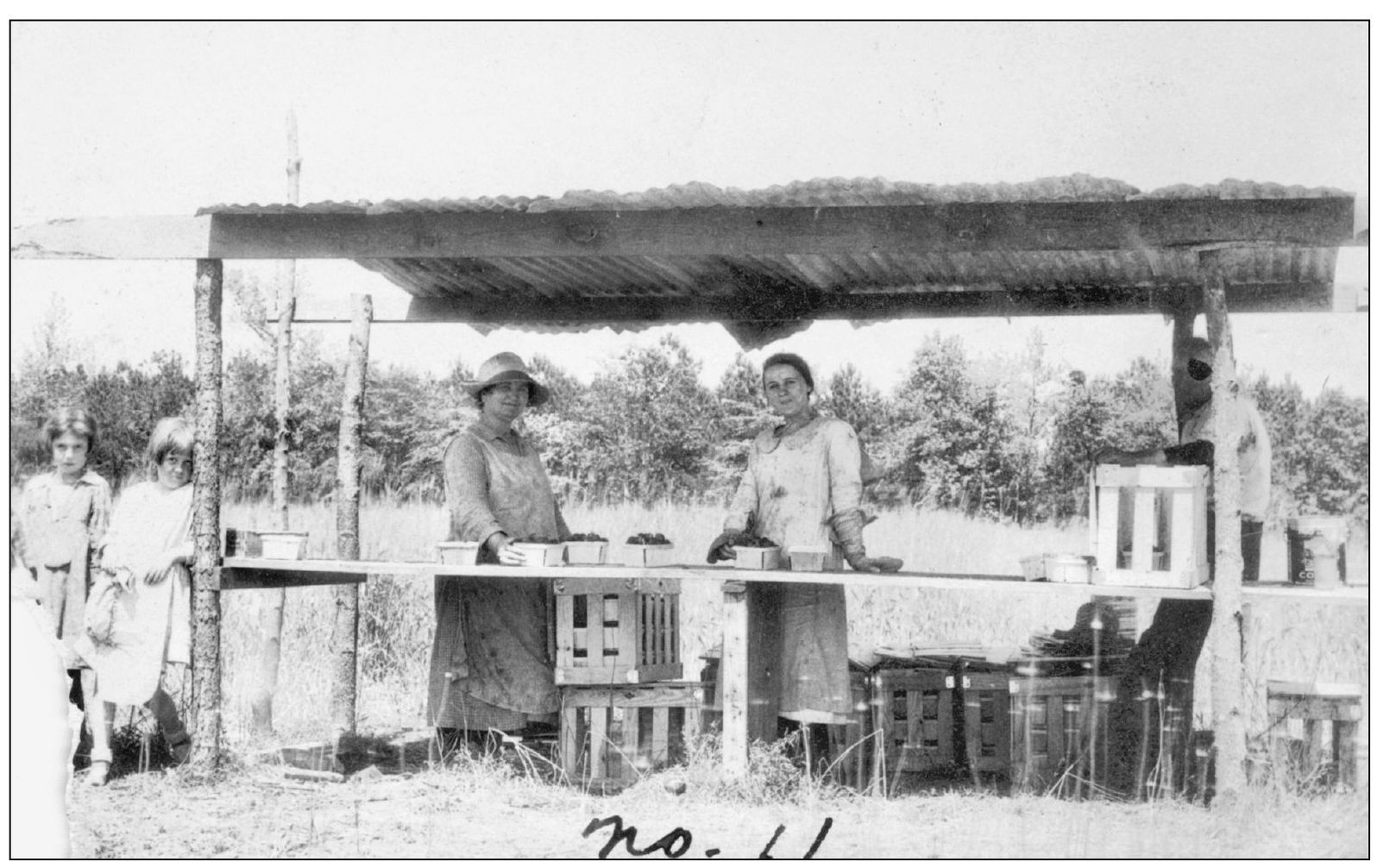

Strawberries were a labor-intensive crop. Pickers, usually women, filled quart baskets and took them to the bower, where the berries would be sorted and packed in 32-quart crates to be taken to the strawberry auction, where buyers would bid on them. This is the T. C. Cobb bower near Onancock in May 1926. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

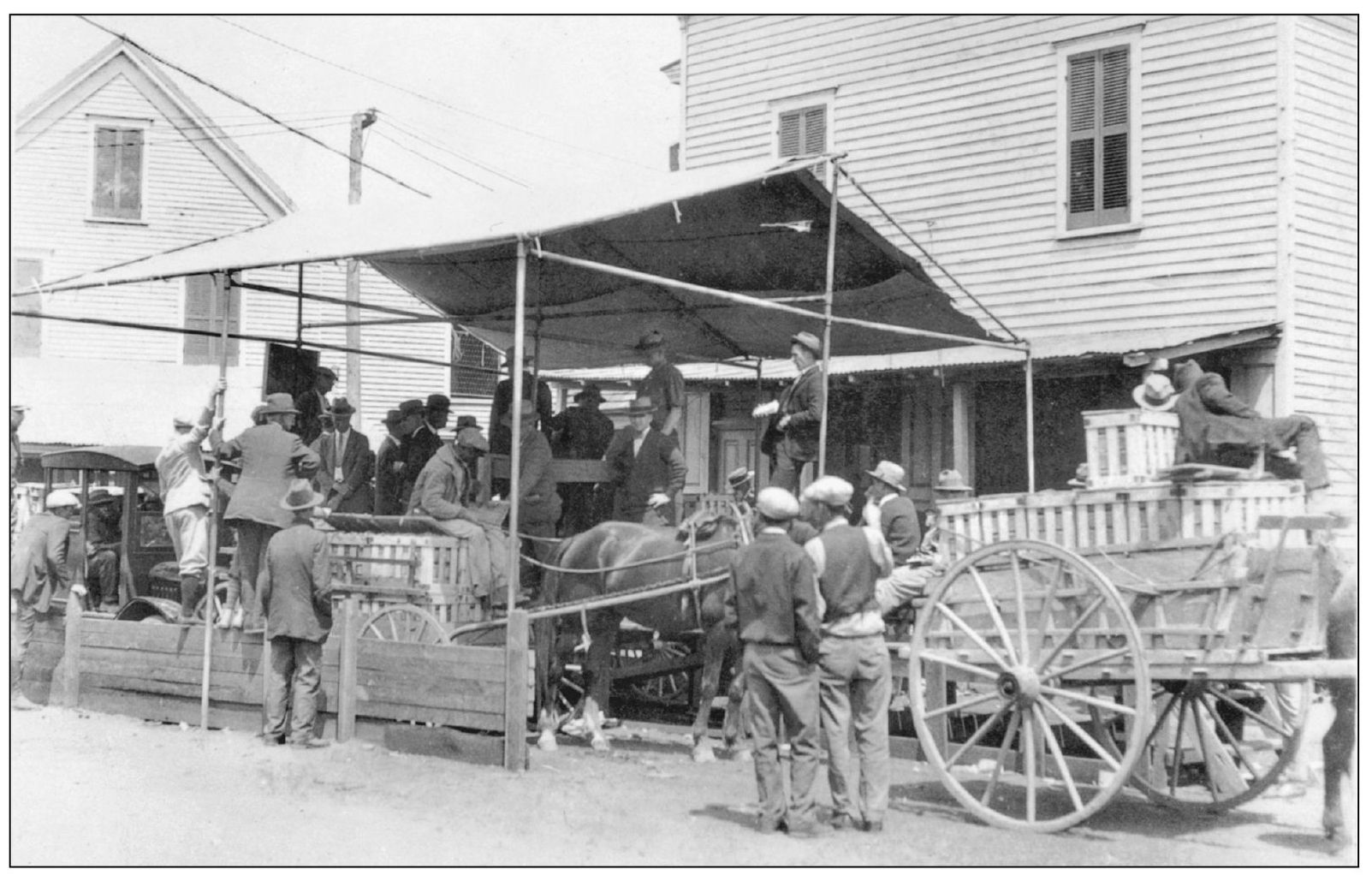

The Eastern Shore of Virginia Produce Exchange was by far the largest marketer of local produce in the 1920s. The exchange mainly dealt in potatoes, but it also ran several strawberry auction blocks, such as this one in Hallwood in June 1926. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

These strawberries were growing in a field near Onancock in 1927. Strawberries are a perennial crop, and many farmers kept a strawberry patch that would produce income in the spring, before the potato crops were matured and ready for market. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

This is the strawberry auction block near the Produce Exchange building in Onley in the spring of 1926. Growers would bring their berries to market, where they would be sold to the highest bidder, usually from off the shore, who would pay the exchange a brokerage fee per crate. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

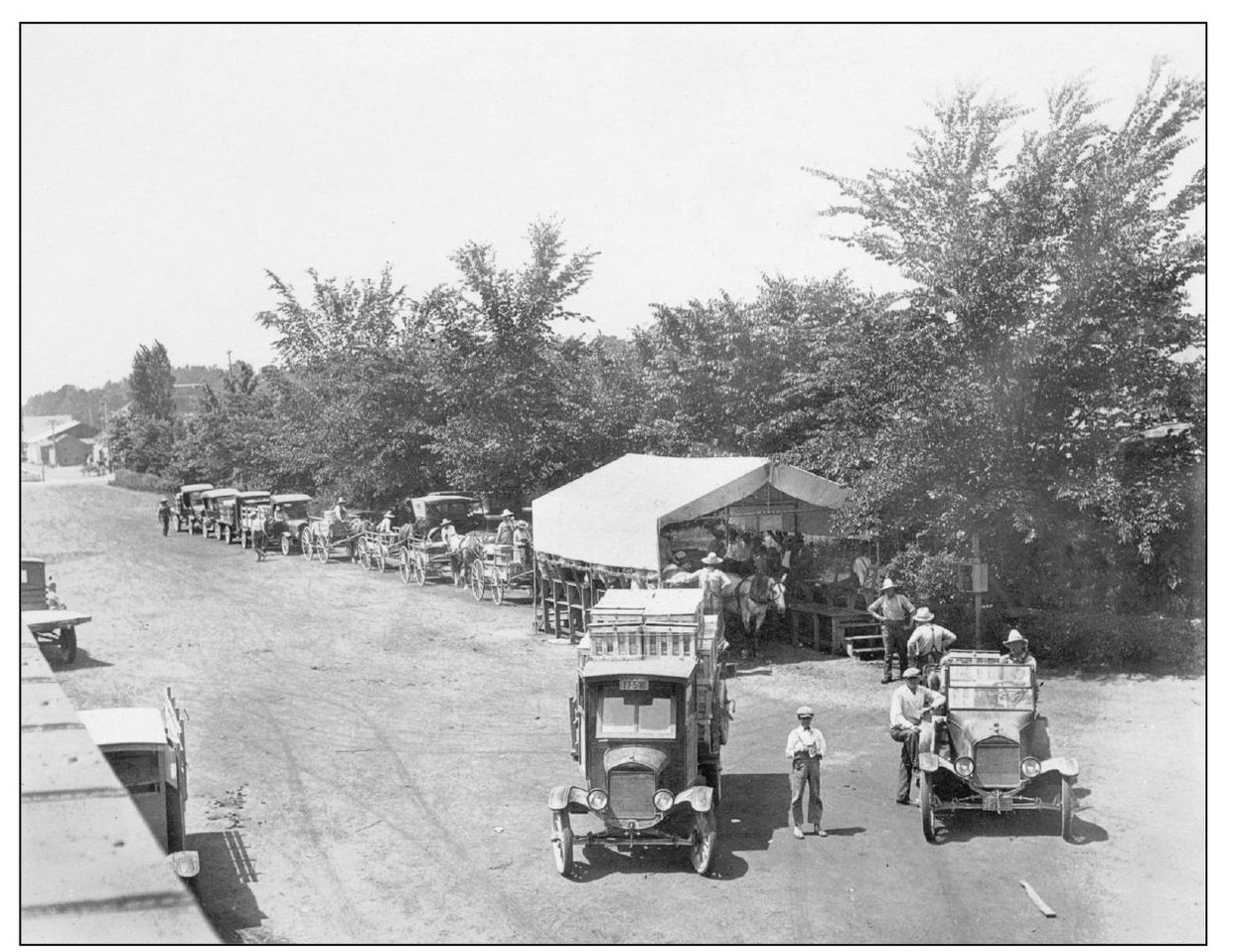

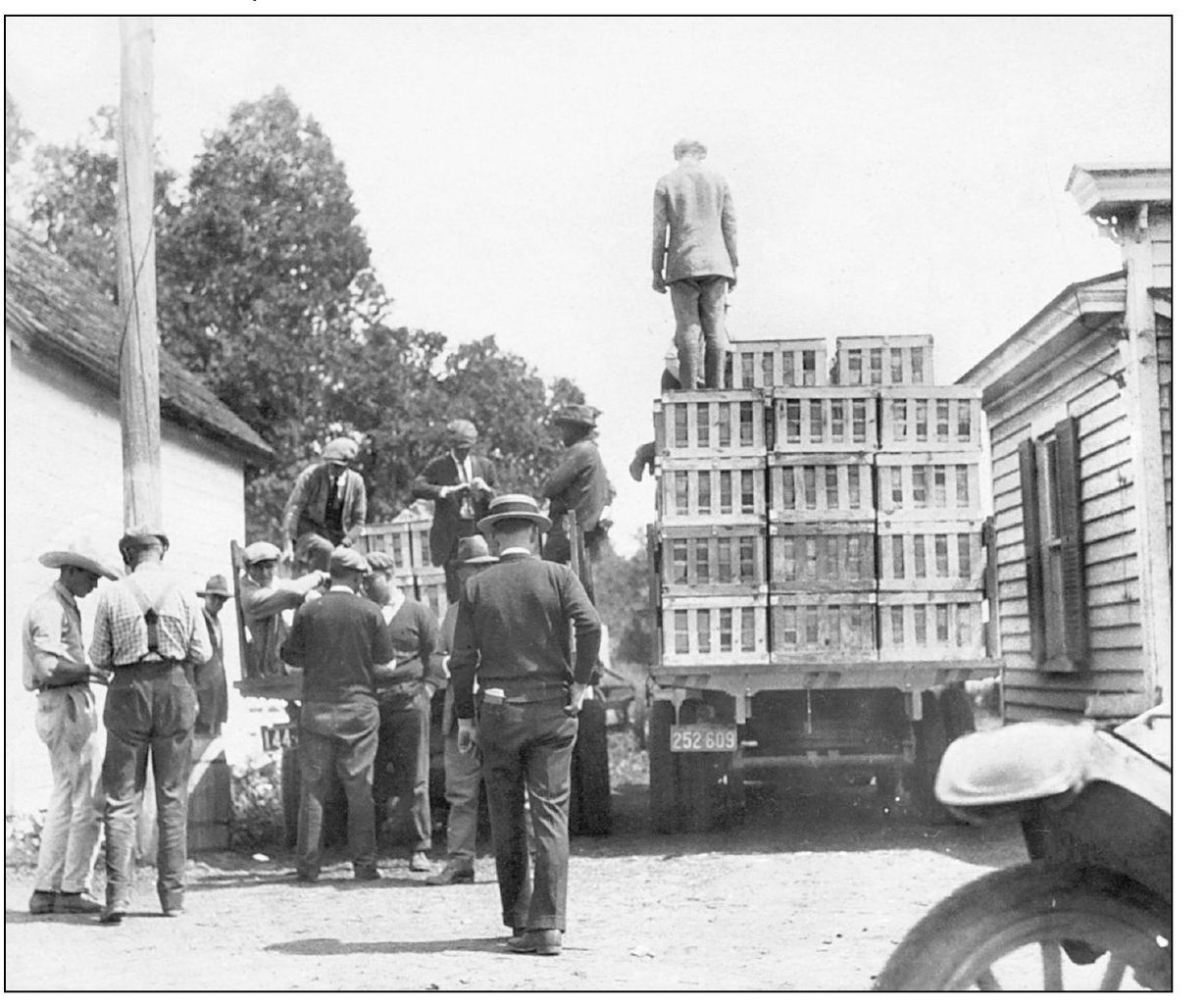

Trucks were lined up at the auction in Onley in 1926 to transport crates of berries. Most were shipped by rail, but some destined for nearby markets were shipped by truck. The exchange building is in the background. The building was constructed in 1910 and is used as a church today. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

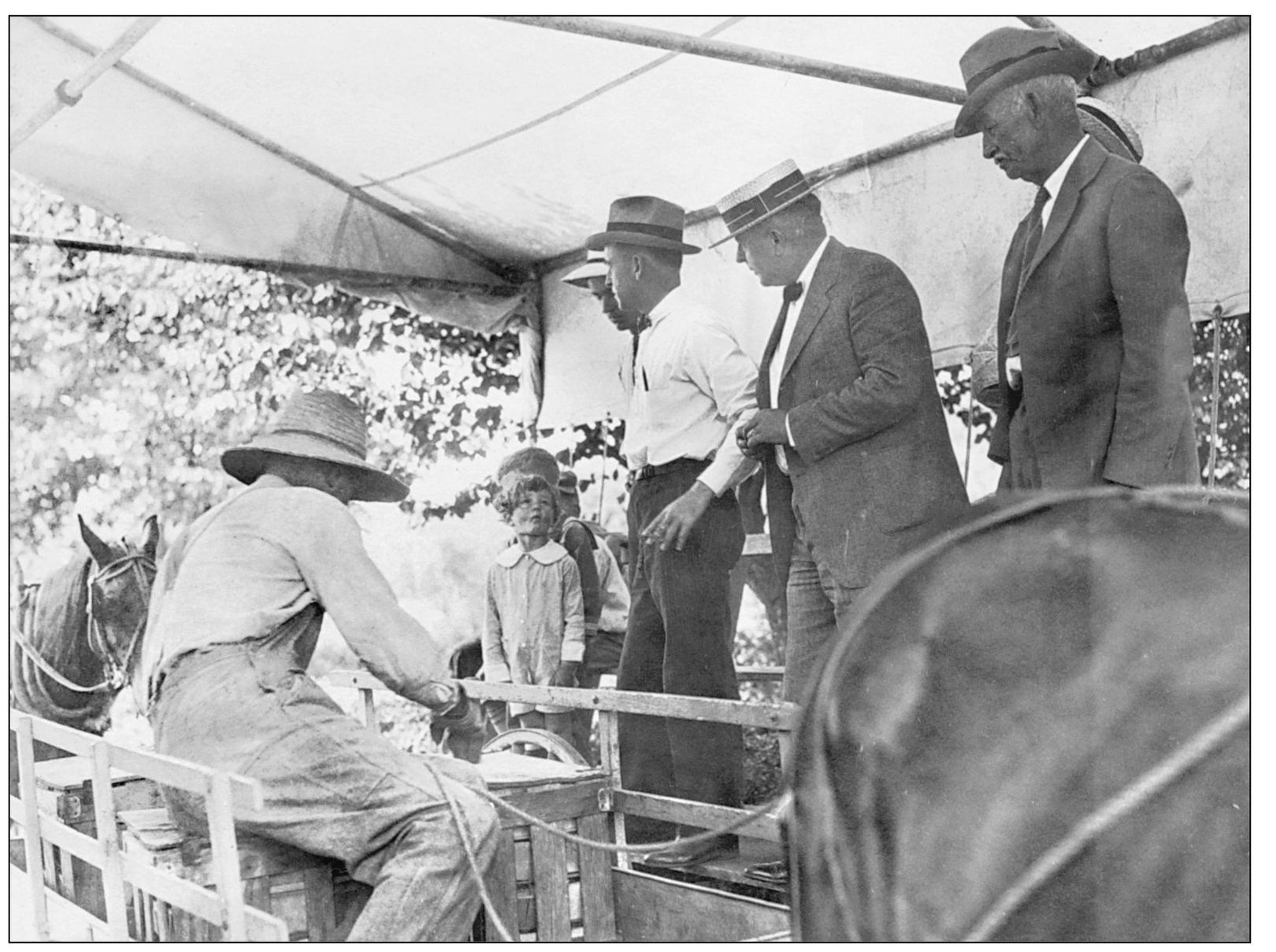

A small child looks on with great interest as the auctioneer sells berries at the Hallwood strawberry block in 1926. Unlike potatoes, strawberries could not be stored until the market conditions were at a peak. They had to be sold when they ripened, and long lines at auction blocks were a common sight in spring in Accomack. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

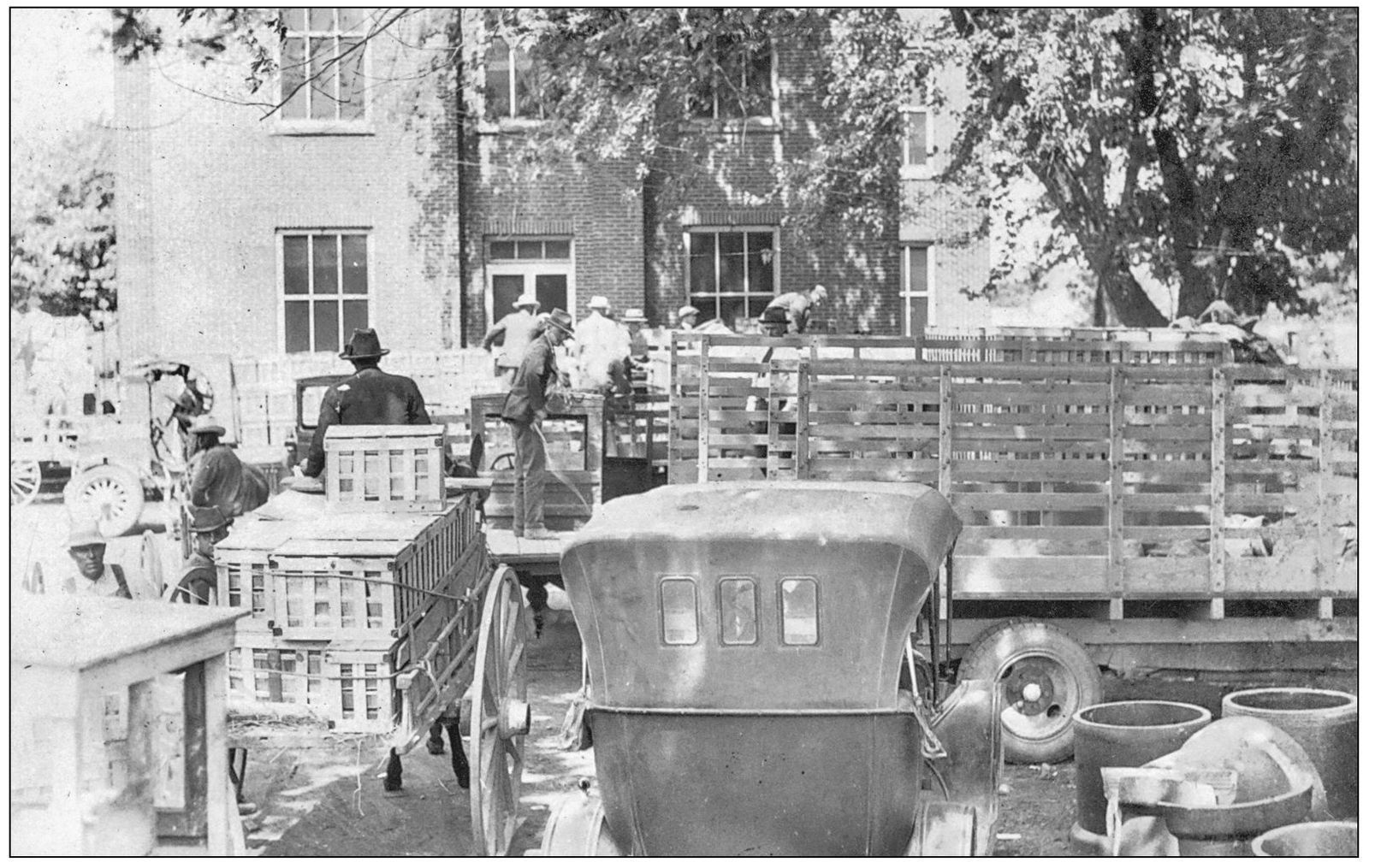

These berries were being loaded at the strawberry block in Onley in May 1926. Onley was for many years the busiest strawberry market in Accomack. The auction block was located between the exchange building and the railroad station. At the height of the season, Onley shipped 65 refrigerated railcars filled with strawberries in a single day. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

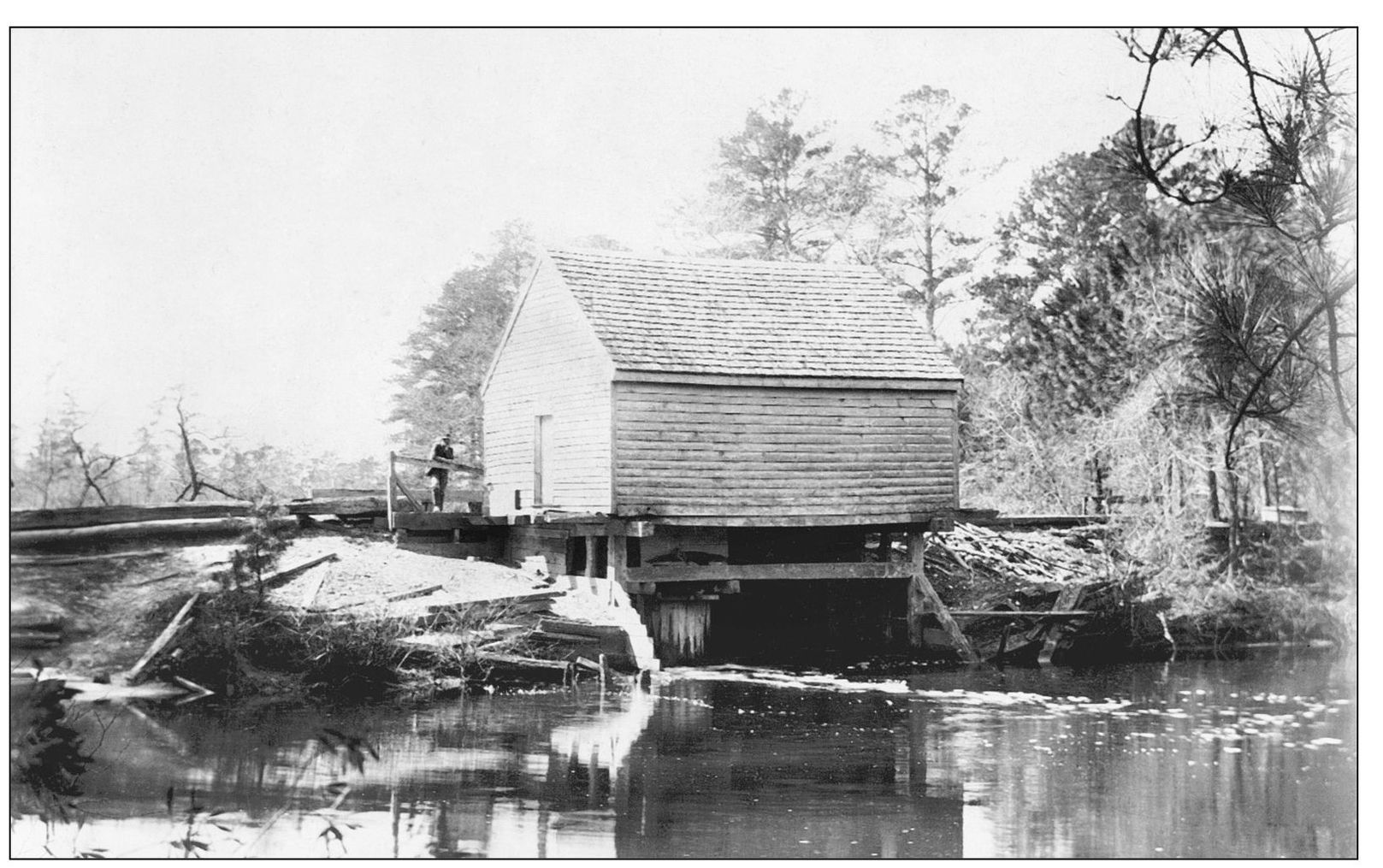

Most communities in Accomack County had mills where local people would take grain to have flour or cornmeal made, usually exchanging a portion of the grain for the task of grinding it. Before potatoes became the major crop in the late 1800s, grains such as corn and oats were the mainstays. This is the Wallops mill in northern Accomack in the late 1800s. (Callahan Collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

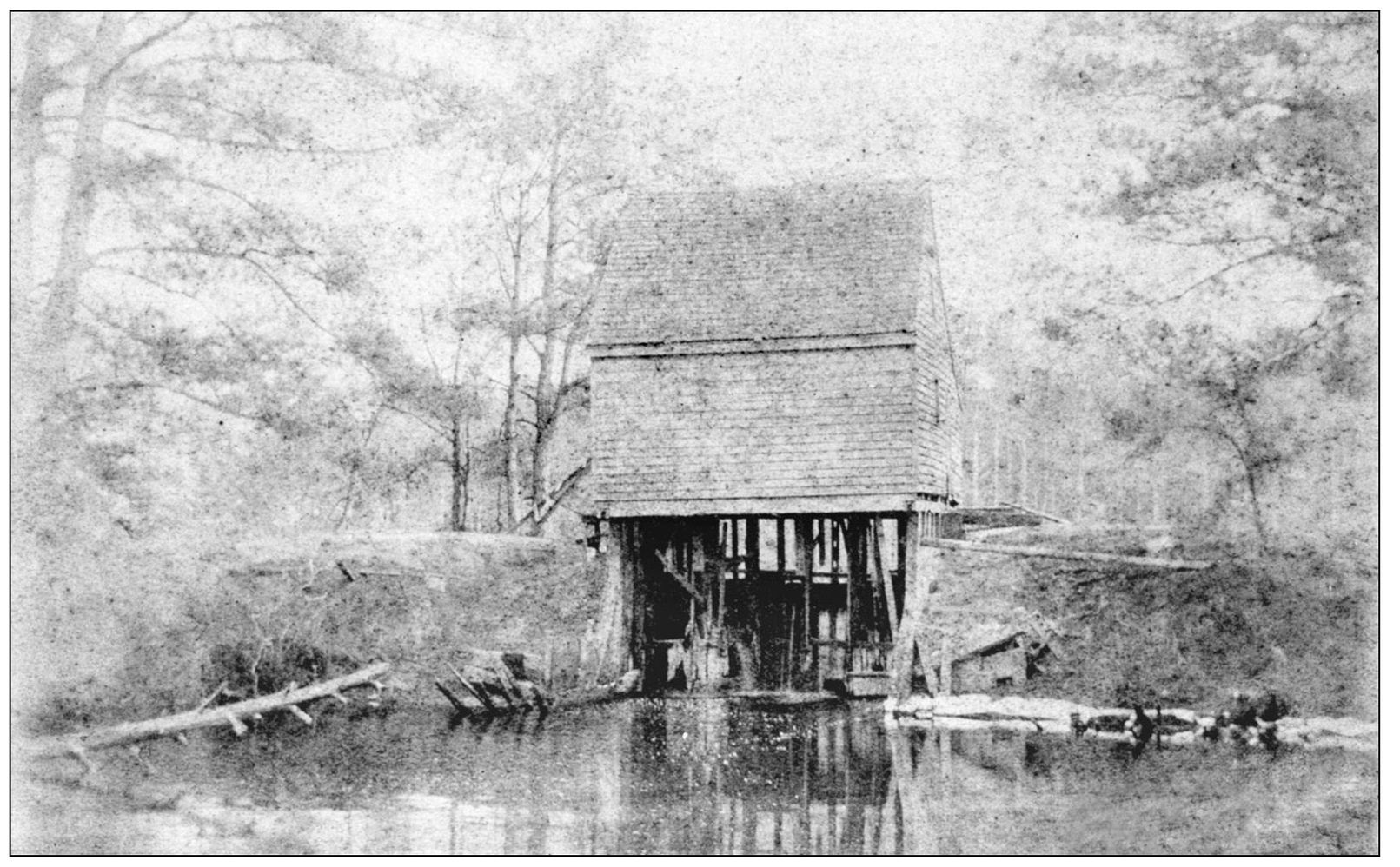

This mill was on one of the headwaters of Pungoteague Creek and was called Luke Luker’s Mill and later Revell’s Mill. An earthen dike was built to dam water, which was then released and used to power the mill. This photograph was taken around 1900. (Callahan Collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

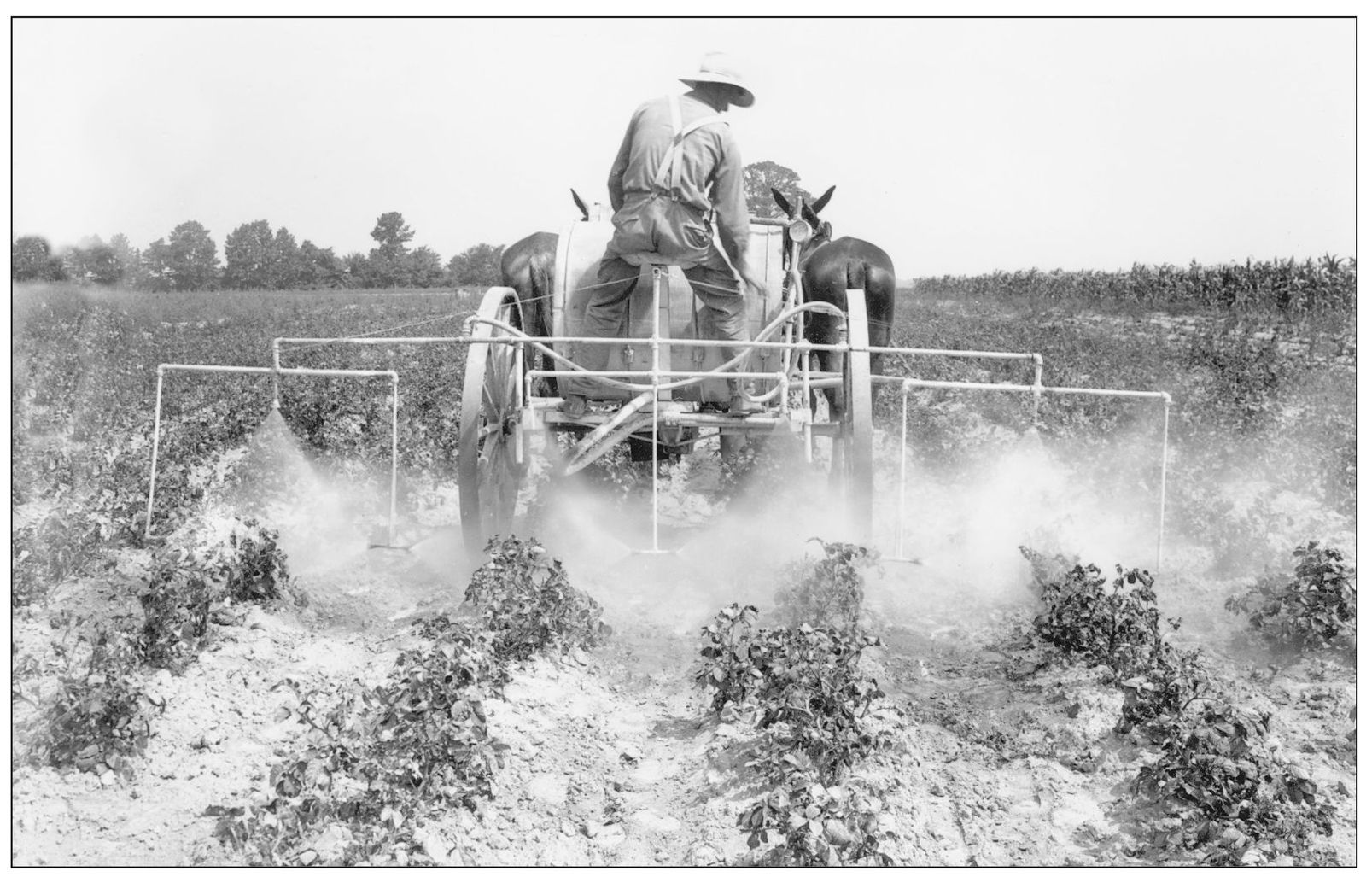

Potatoes were the money-making crop for Accomack in the first half of the 20th century. In 1900, a little more than one million bushels were harvested; by 1929, that figure topped 10 million. Here a horse-drawn sprayer is dusting potato plants, probably for potato beetles. (Courtesy of the Hampton Roads Agricultural Research and Extension Center.)

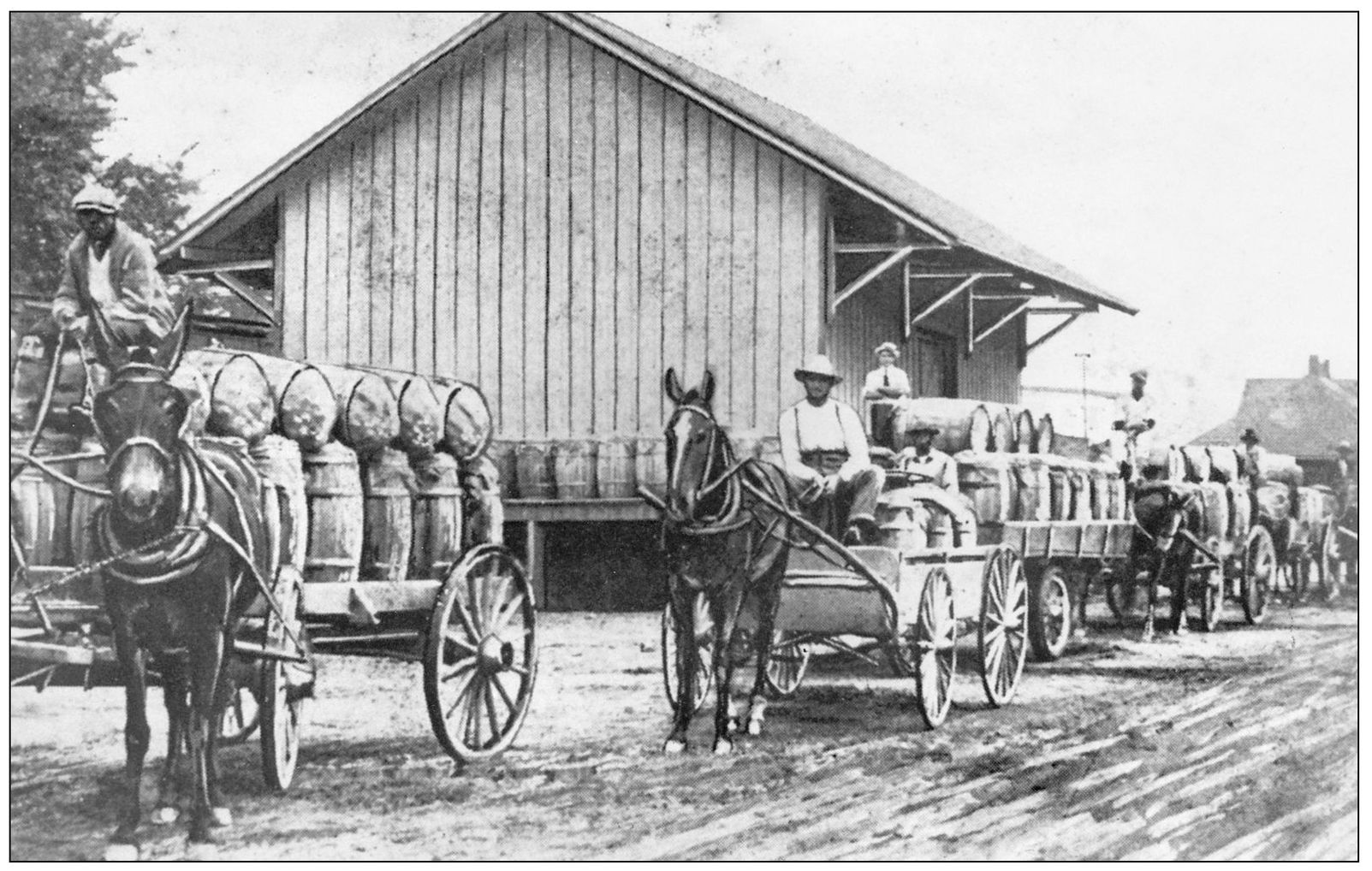

Most local communities had barrel houses in the early 1900s where containers would be made for potatoes, cabbage, and other crops. These wagons are loaded with barrels filled with potatoes to be shipped to market on the railroad. By the late 1920s, bags were being used as a shipping alternative to barrels. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

Potatoes and strawberries were not the only income producers for local growers. This farmer near Onley had a flock of turkeys, probably ready for the Thanksgiving market when this photograph was taken in October 1929. Farmers also raised hogs, both for market and for personal use. Hog killing was a winter tradition in Accomack, and farm families would fill smokehouses with hams, bacon, sausage, and delicacies such as homemade scrapple and souse. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

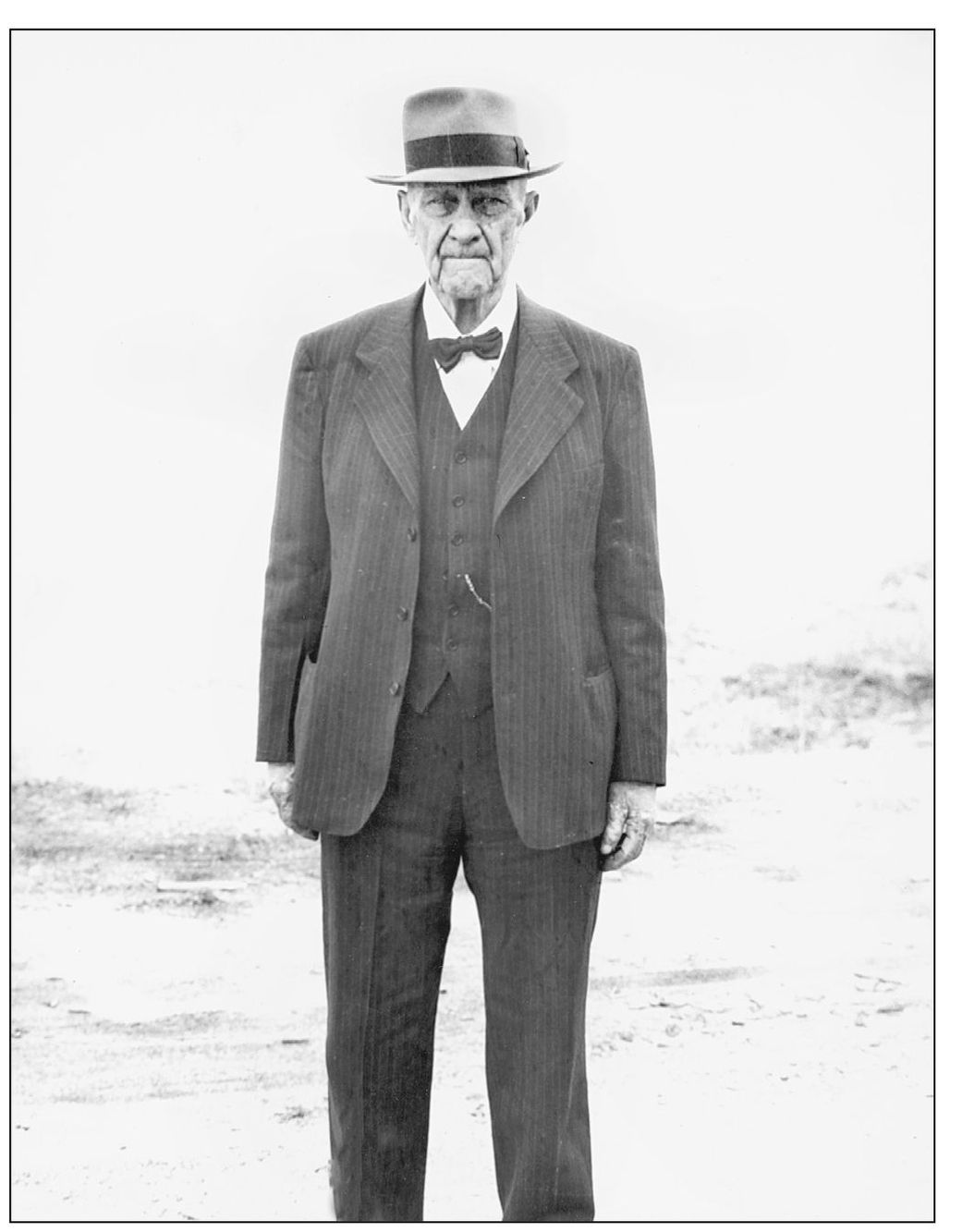

Smith K. Martin II was a prominent Harborton businessman who was highly regarded throughout Accomack County. He served on the original board of directors of the Farmers and Merchants National Bank and was on the board of the Eastern Shore Produce Exchange. This photograph was taken around 1950. He died in 1952 at age 90. (Courtesy of Webster Martin.)

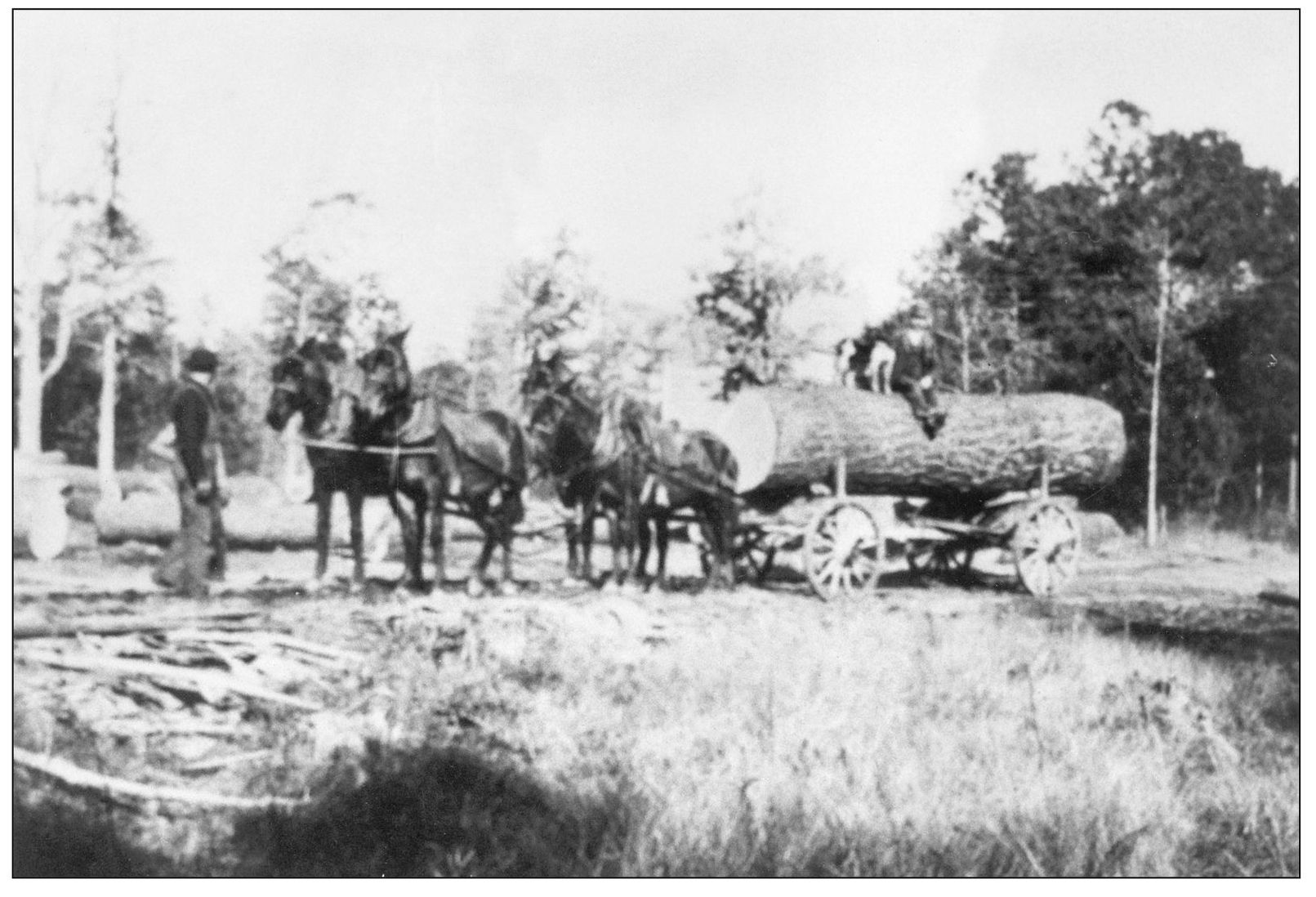

Smith Martin was a principle in the Martin-Mason Company, which ran a lumber and building supplies business in Harborton. Below, a mule team transports a huge pine log to the mill around 1890. Seated on top was Martin with his bird dog, Tilghman. The building supply store still stands and is today a private residence overlooking the Harborton waterfront. (Courtesy of Webster Martin.)

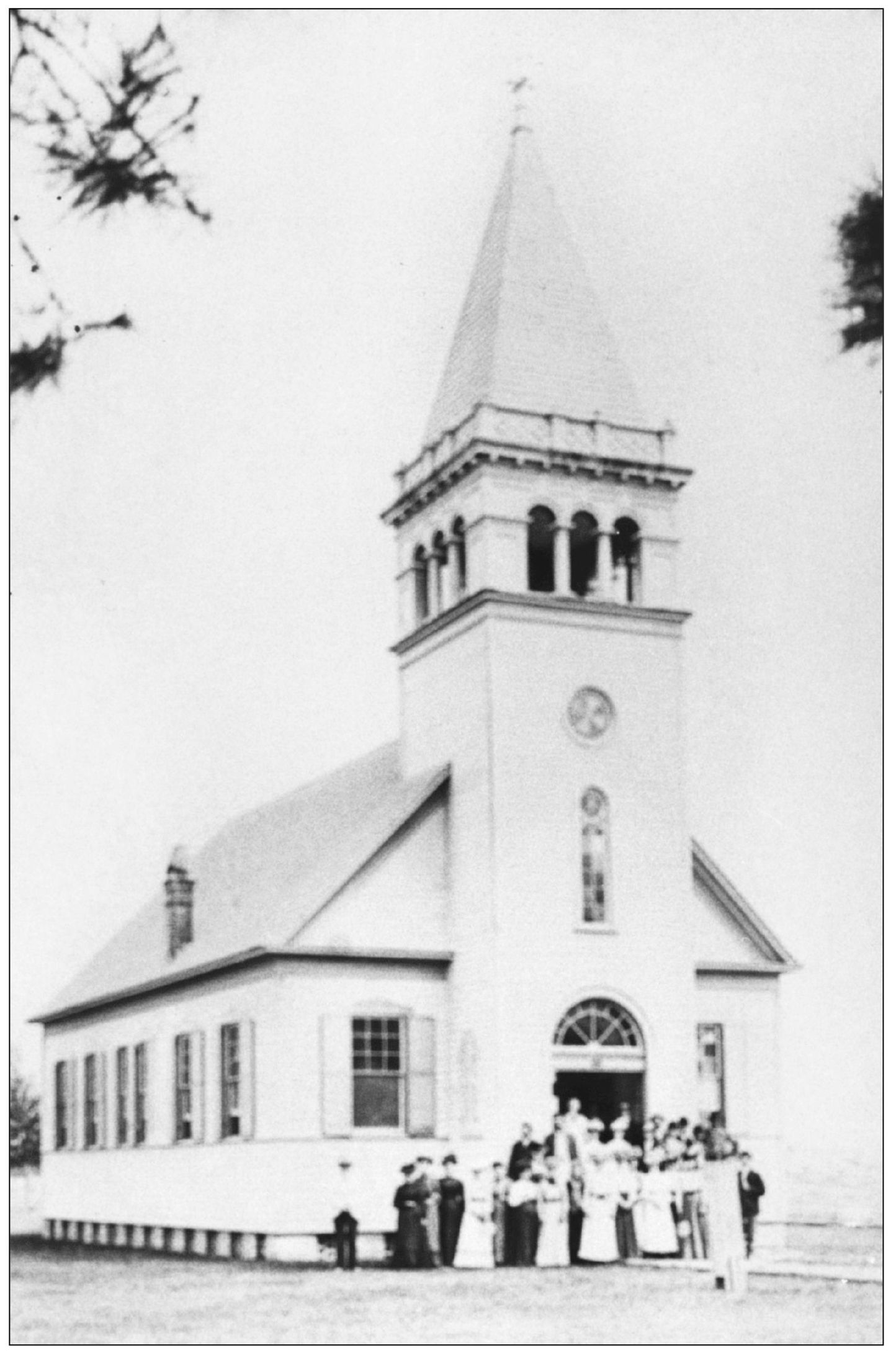

The Harborton Baptist Church was built in 1894 on the corner of Harborton Road and Adams Lane, and enjoyed a large congregation when the town was a busy steamboat port. As the shipping business dwindled in the early 20th century, the population of Harborton dropped, as did attendance at the church. It closed its doors during World War II and was dismantled in 1945. (Courtesy of Webster Martin.)

Pungoteague Hotel was a popular gathering place and a haven for travelers in the late 1800s. This little village played a prominent role in Accomack County history. The first play in America, Ye Bear and Ye Cub, was performed in 1665 at Fowkes Tavern here. Pungoteague served for a period as the county seat. And British forces attacked the local militia along Pungoteague Creek in May 1814 during the War of 1812. Nearby Hoffman’s Wharf, now known as Harborton, was a busy port during the steamship era, and even before that, Pungoteague Creek was an important shipping corridor. At low tide, ballast stones can be seen along the creek, evidence of sailing ships during Colonial days. (Callahan Collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

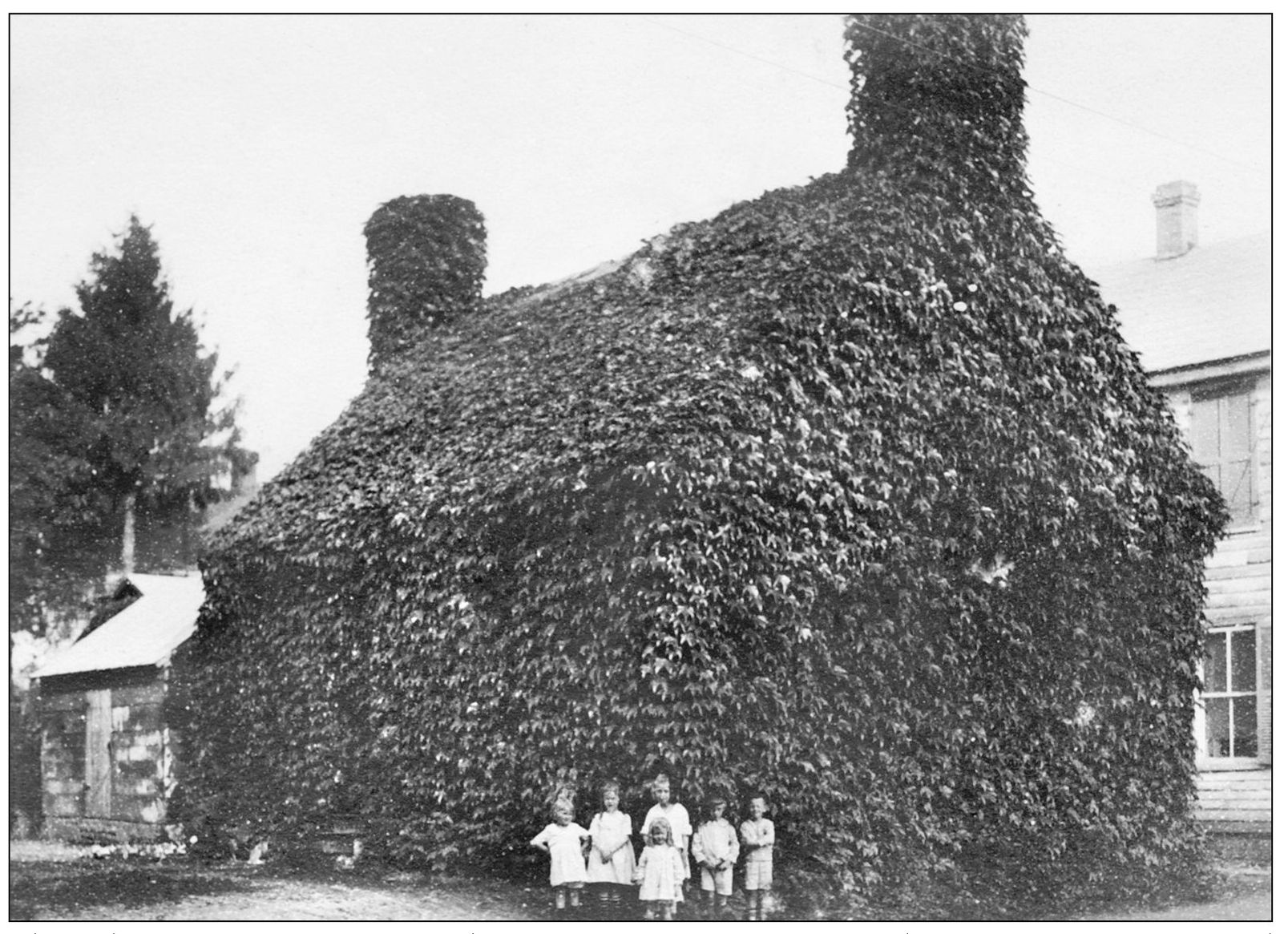

The Debtors’ Prison in Accomac, the seat of government, is one of the county’s most recognized historical landmarks. The building was constructed when Accomac was known as Drummondtown, so named because the land where the town is situated belonged to Richard Drummond. In 1786, the town had a brick courthouse, a jail, and this building, which then was used as living quarters for the jail keeper and his family. (Callahan Collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

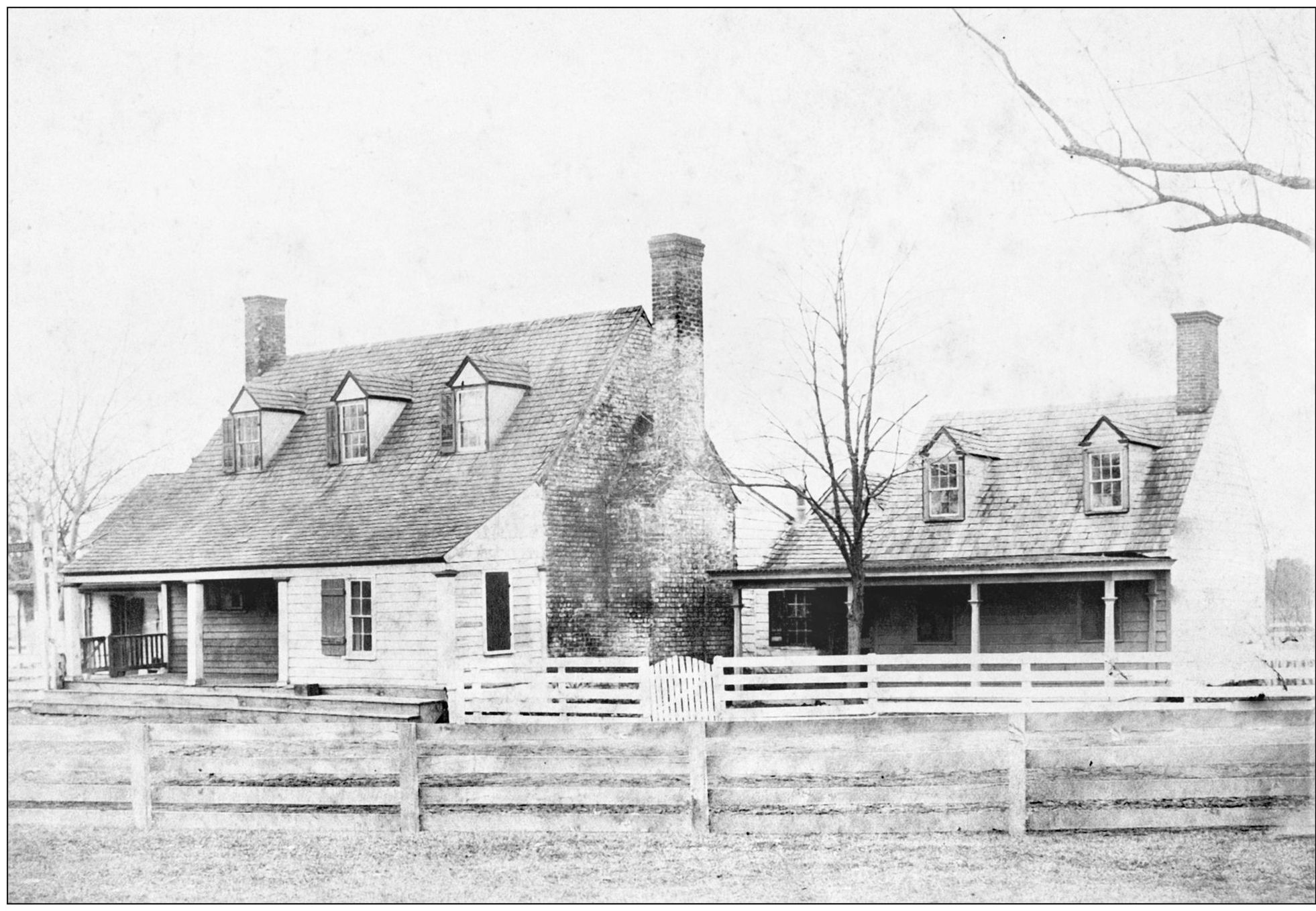

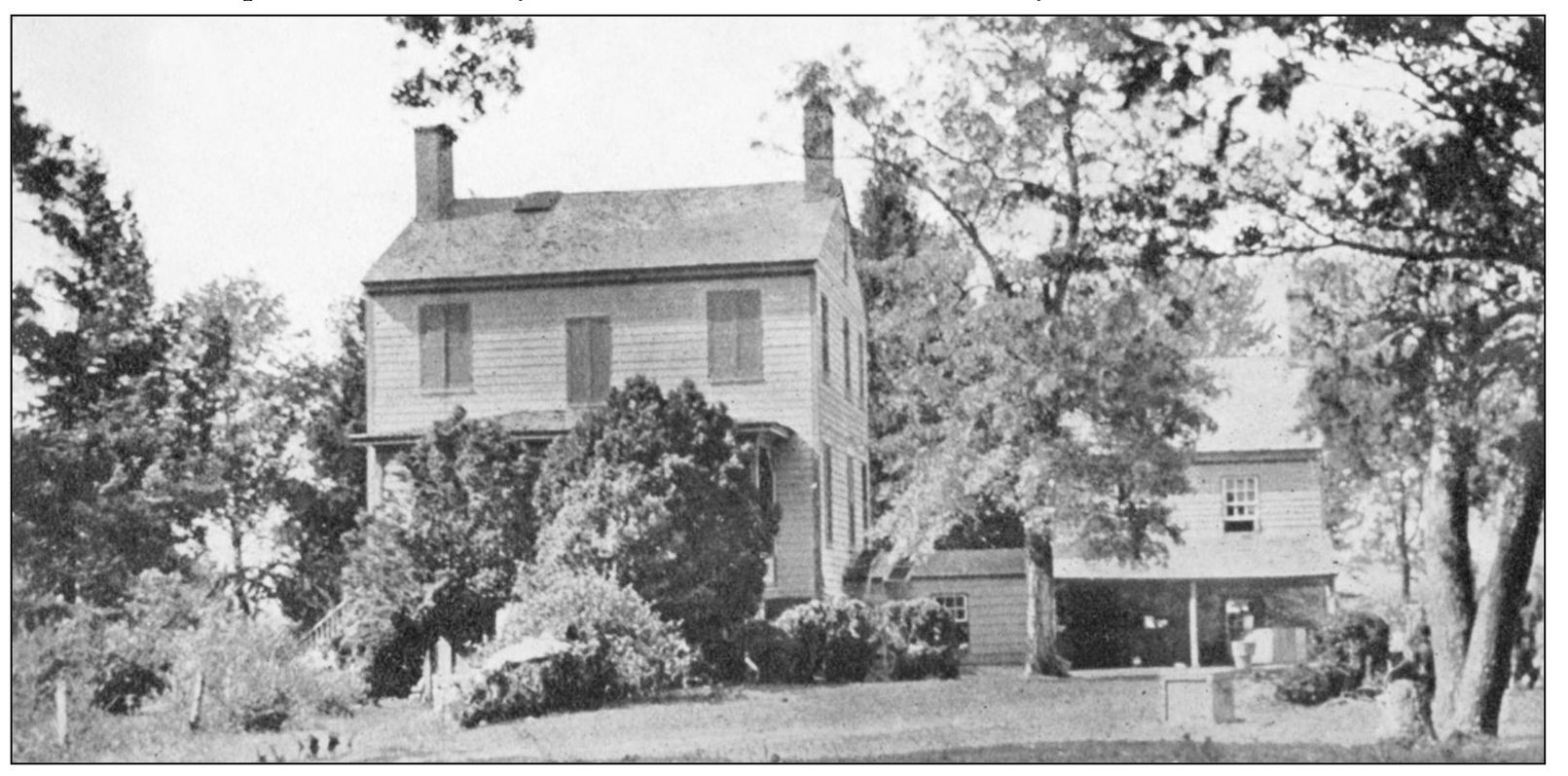

Onley, on the north bank of Onancock Creek, was the home of Gov. Henry A. Wise, the only Virginia governor (1855–1859) to have come from Accomack County. The house, built in 1843, is not typical of Eastern Shore architecture; the late historian Ralph Whitelaw speculated that it was designed by a Philadelphia architect employed by Wise’s wife, who was from the North. (Courtesy of the Eastern Shore Railroad Museum.)

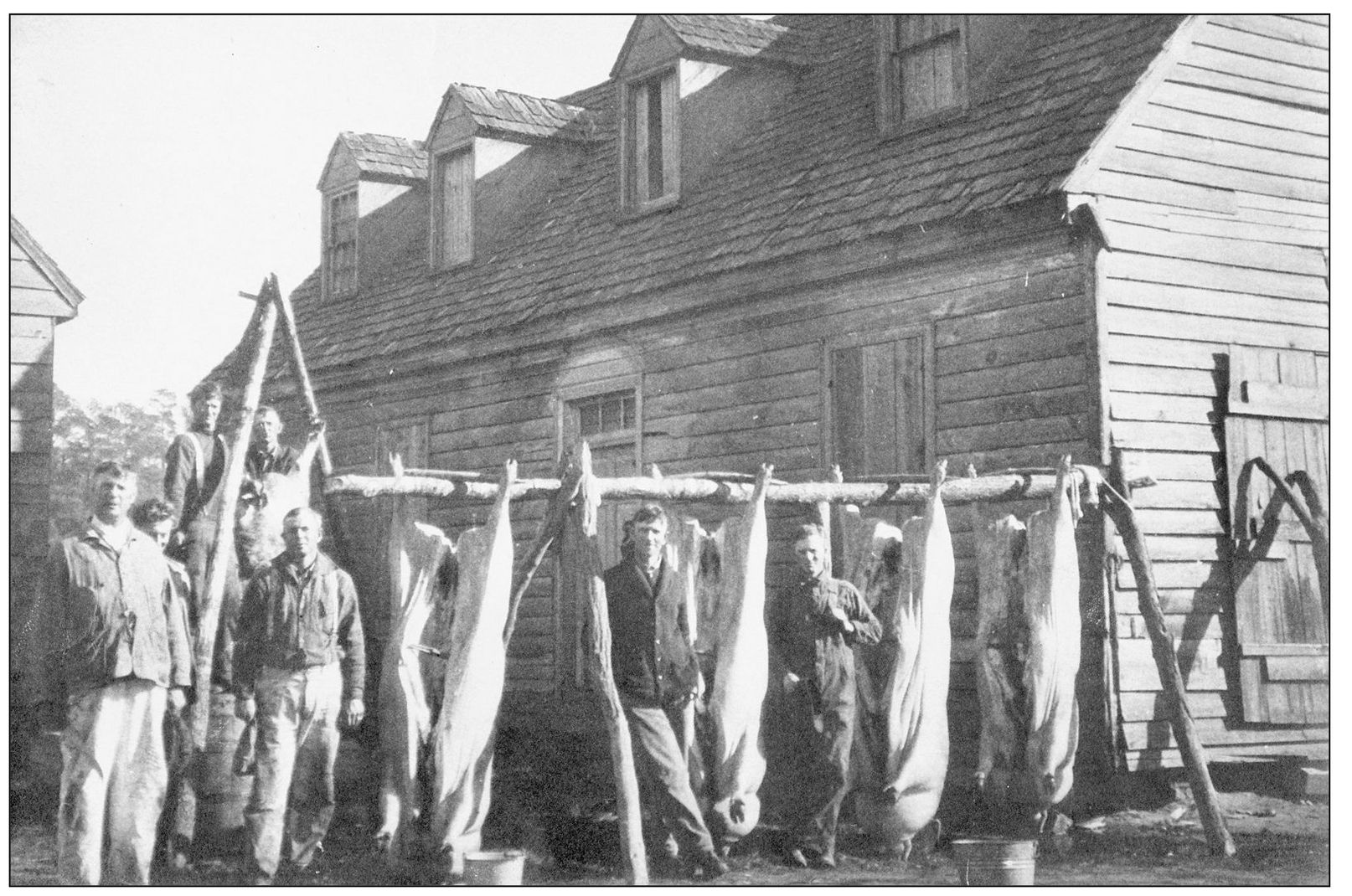

Hog killing was a winter tradition in Accomack County, a means of preparing and preserving meats that would last through the winter. Some farmers performed the ritual themselves, and others hired groups who were experienced in the task. This photograph was taken at the Knute Anderson house in Wachapreague. (Courtesy of the Randy Lewis family.)

U.S. Route 13 is a busy four-lane highway today, but prior to the 1920s, much of it did not exist. This is the Zion Baptist Church, located on what is now Route 13 north of Accomac, in quieter days, with a cow grazing on the lawn. Route 13 generally followed the path of this road in northern Accomack. A new road was built along the railroad track in southern Accomack. The highway opened in 1931 and was known as Stone Road. (Courtesy of O. W. Mears.)

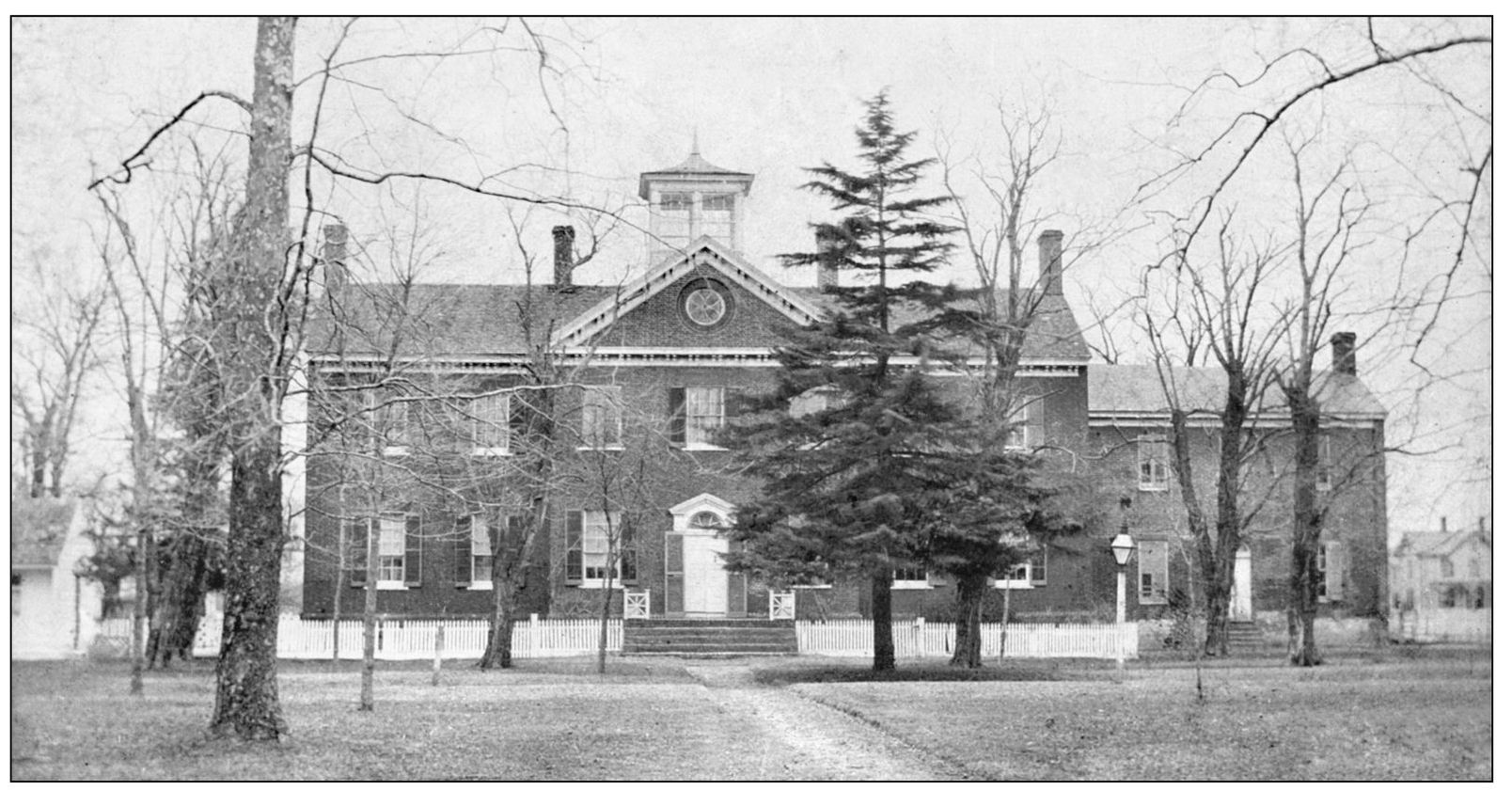

Ker Place in Onancock is home of the Eastern Shore of Virginia Historical Society and is a museum depicting early Eastern Shore life. This handsome brick mansion was started in 1797 and completed, with the exception of a more recent annex, early in the next century. This photograph, taken in the early 1900s when it was a private residence, shows the mansion with a cupola, since removed, and a white picket fence. (Callahan Collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

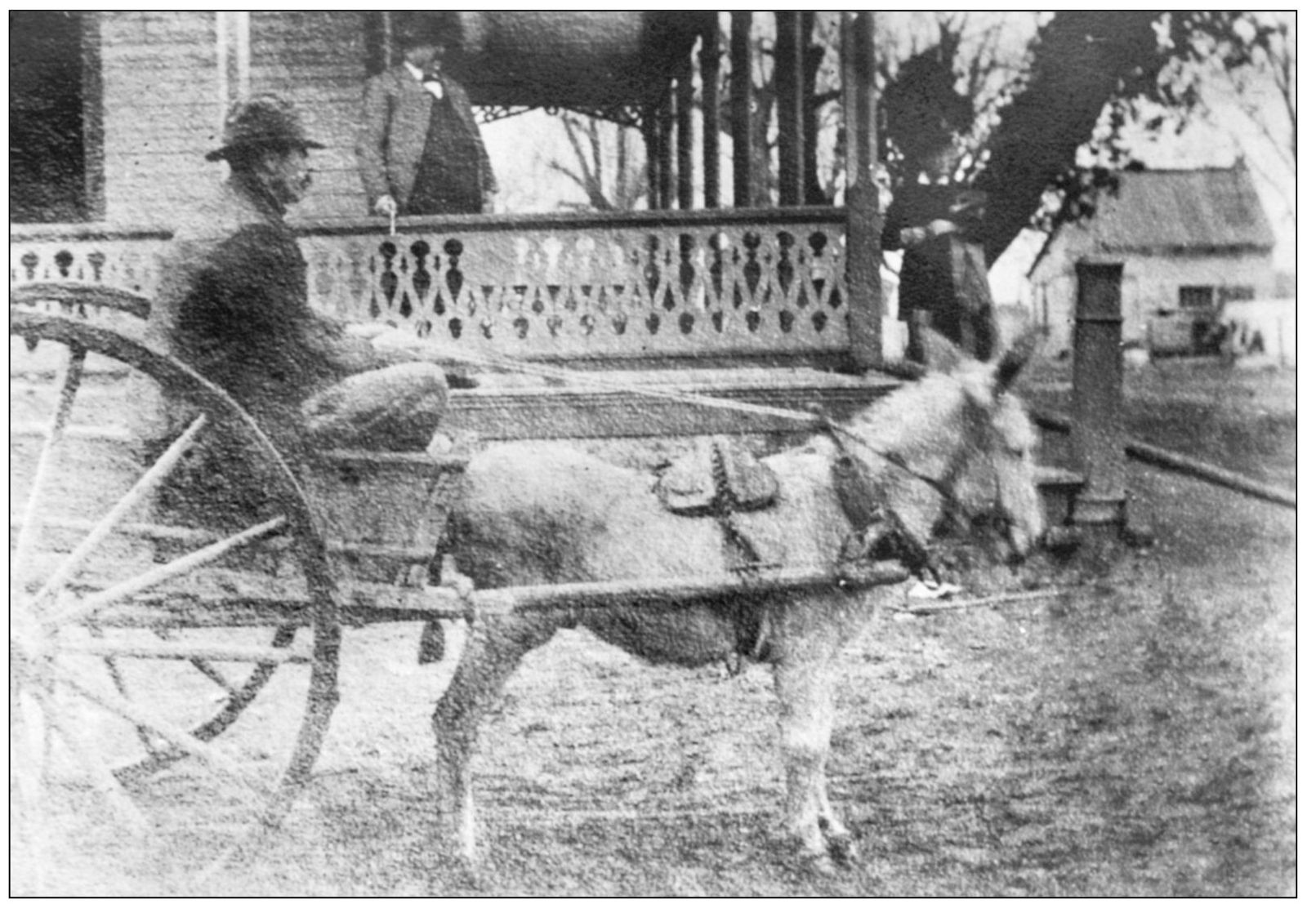

Still a summer presence is the “fish man.” In 1890, seafood vendors, such as this one in Accomac, would travel the streets of town selling fresh fish and other items from the back of their carts. In the mid-20th century, fish men were commonplace in local communities. If one heard a horn blowing down the street, chances are it was the fish man announcing his presence. There still are a few around. (Edmonds Collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

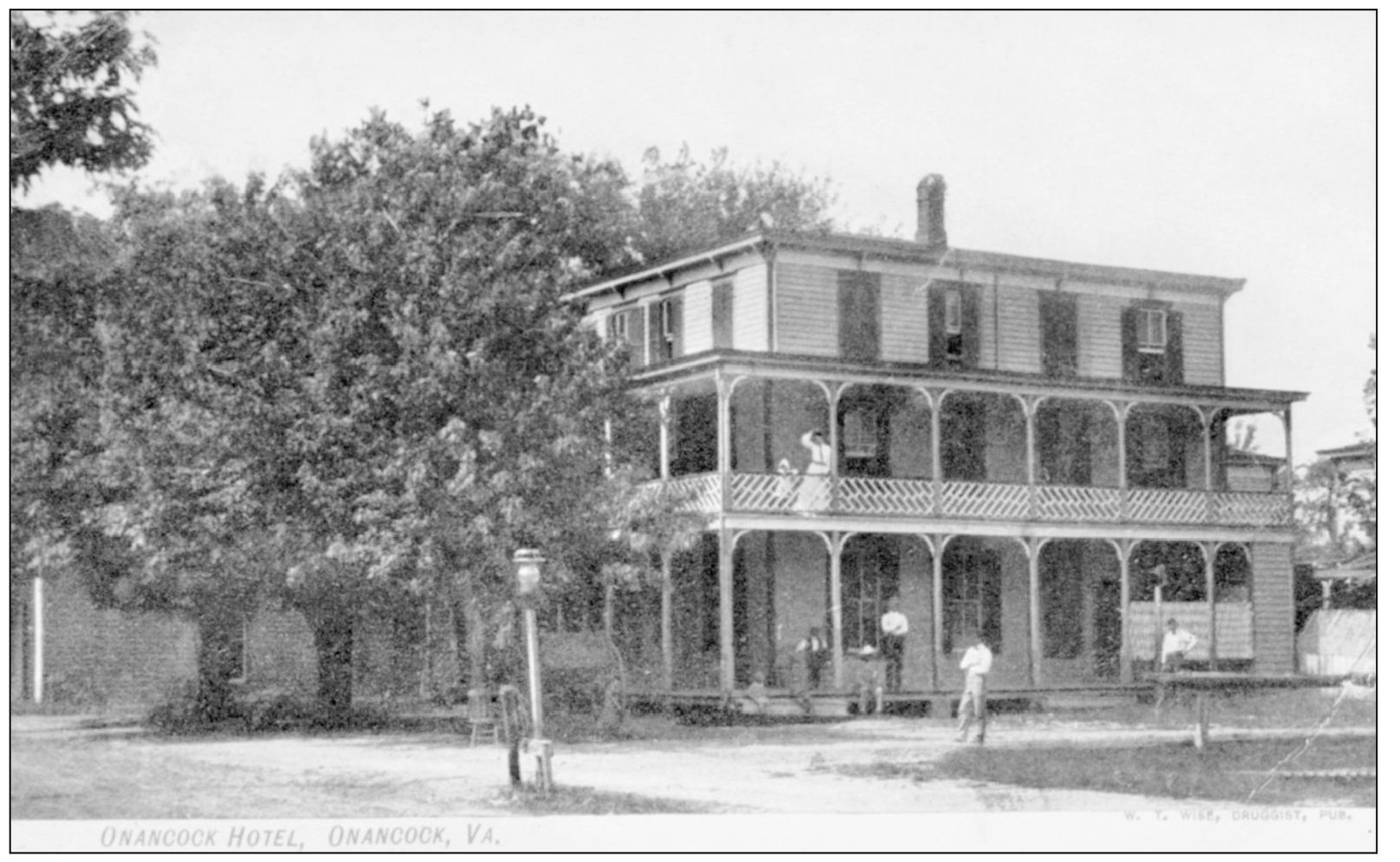

Benjamin T. Parker built a hotel in Onancock around 1870 on the site of the present U.S. Post Office building. The hotel was lost to fire in 1887 and replaced by this new facility, the Grand Central Hotel, a three-story building with wraparound porches. The hotel changed owners and names several times over the years and was sold to the federal government in 1934 when the new post office was planned. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

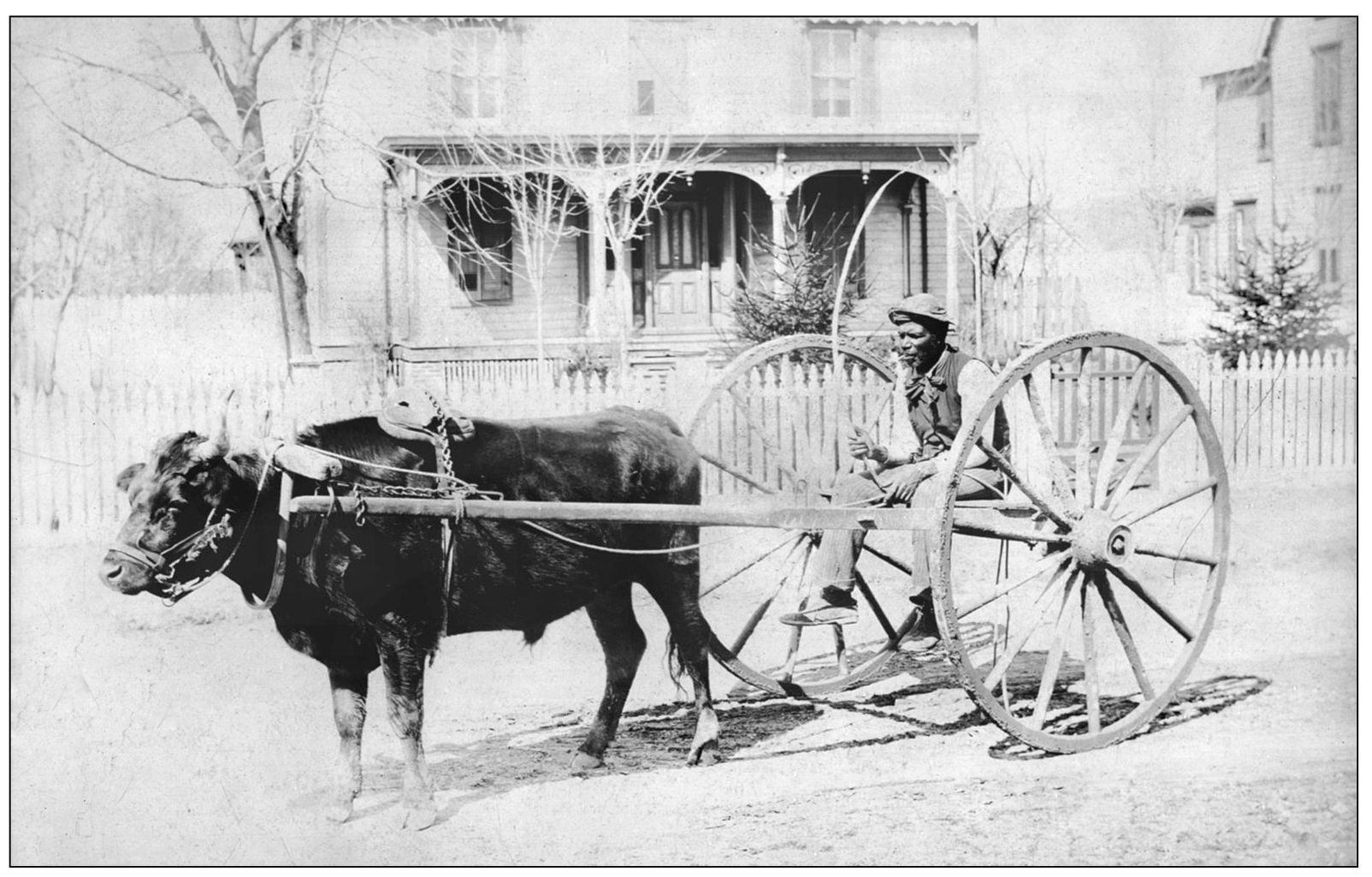

This photograph was taken on Market Street in Onancock around 1890 by Griffin Callahan. The photographer’s notation reads simply, “a typical Eastern Shore vehicle.” (Callahan Collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

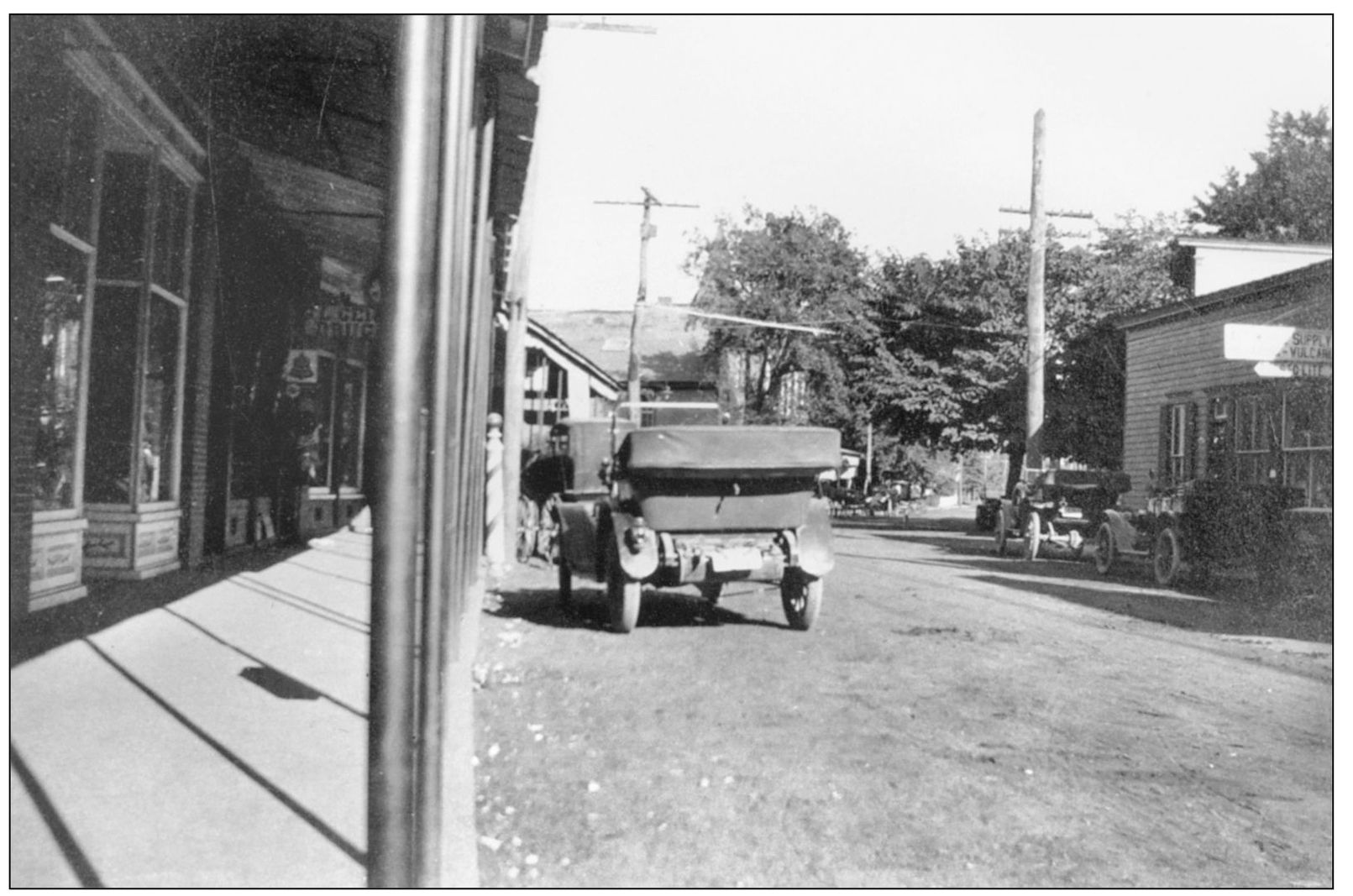

Market Street in Onancock in 1914 had dirt streets and sidewalks covered with canopies to protect shoppers from the elements. Parking protocol was a bit more relaxed in 1914 than it is today. (Courtesy of I. W. Bagwell IV.)

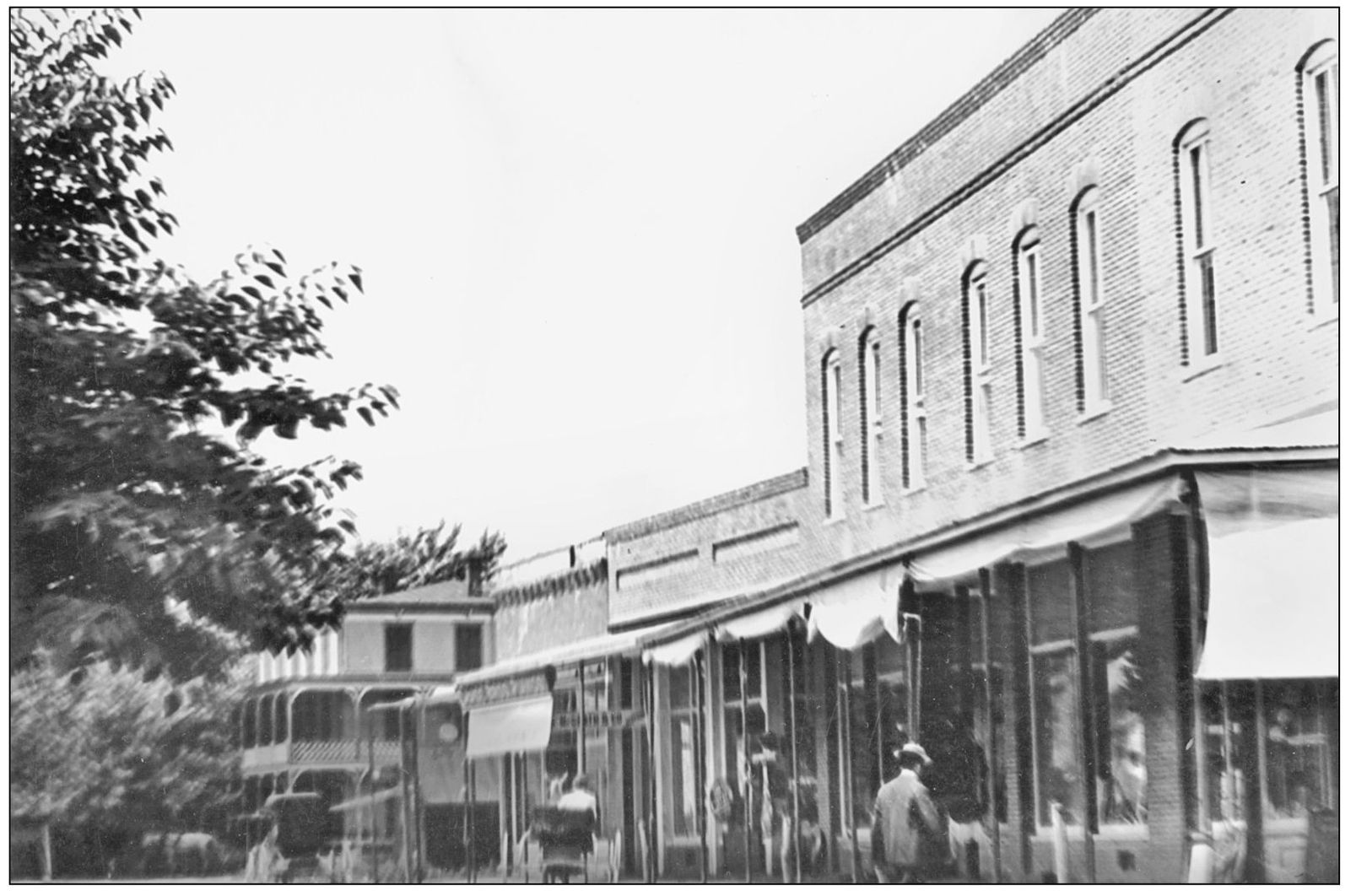

This Market Street scene was taken in 1905 by Dr. John Robertson. Wise’s Drug Store was on the corner of Market and North Streets, and the Grand Central Hotel can be seen down the street. (Robertson Collection, courtesy of ESVHS.)

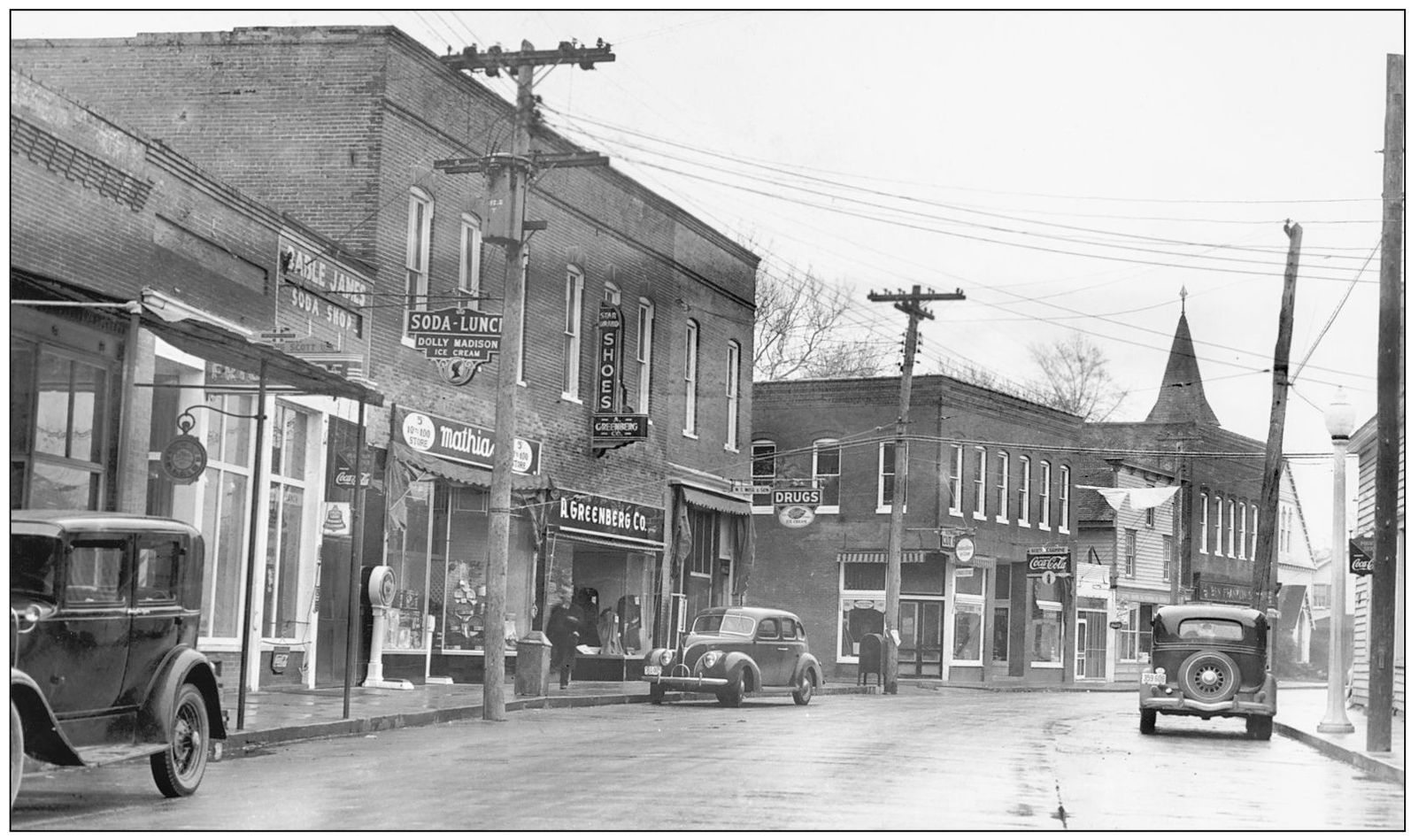

A 1937 photograph of Market Street shows streets lined with traffic during the Potato Blossom Festival. The building on the far right is the Auditorium Theatre, currently the site of the North Street Playhouse. The steeple in the background is that of the Onancock Baptist Church. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

This is a 1937 view of Market and North Streets, taken from the west. Businesses on the left side of the street include Scott’s Furniture, Babel James’ Soda Shop, Mathias’ Five and Dime, the A. Greenburg clothing store, and Wise’s Drug Store. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

North Street in Onancock in 1937 was a busy place. Scott and Carmine’s Hardware is on the right. The business would later move across the street, where a grocery store is located in this photograph. In the distance is the office of Dr. John Robertson (left) and the hotel that was replaced by the Department of Motor Vehicles building. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

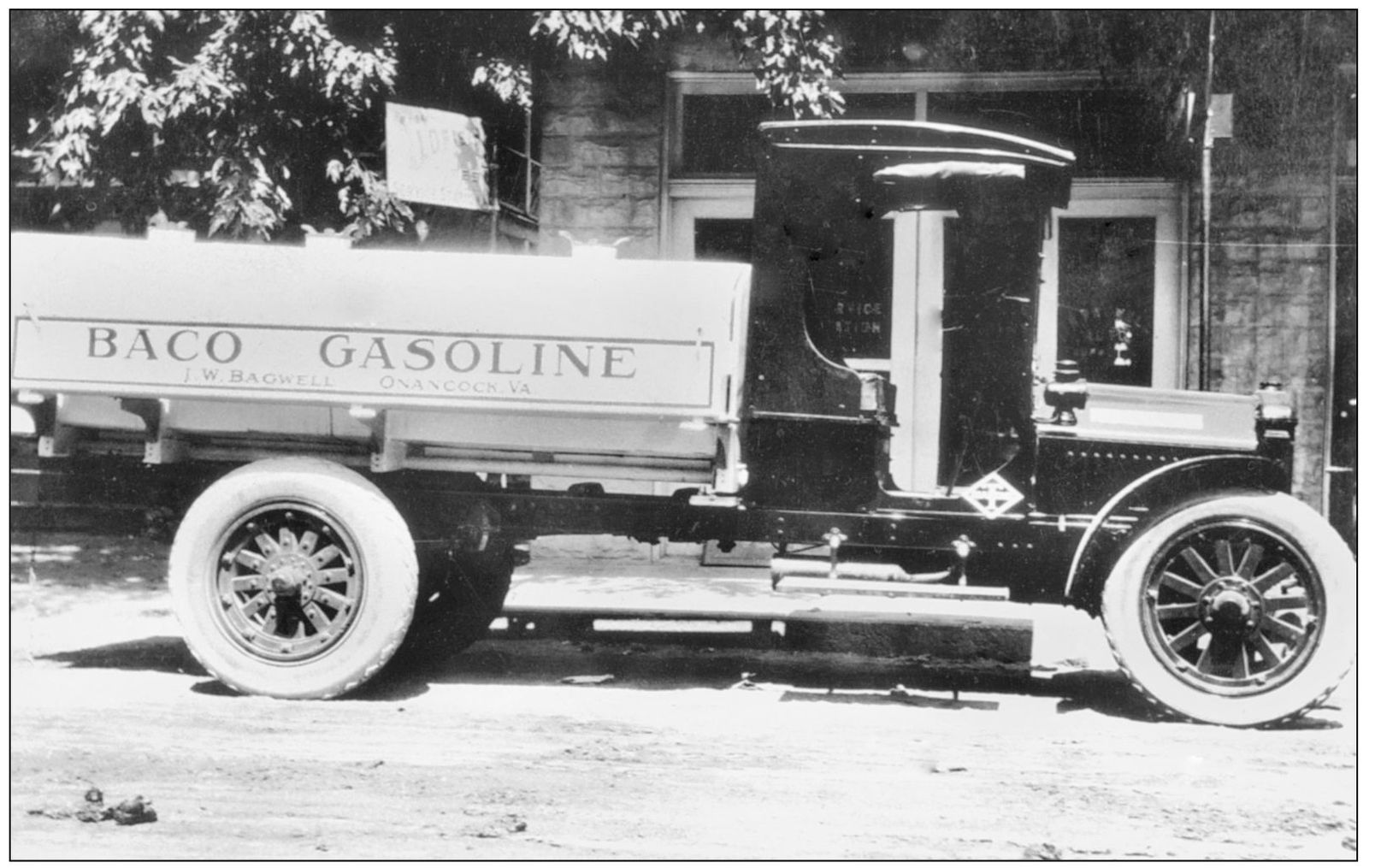

One of the early businesses in Onancock still operating today is the Bagwell Gas and Oil Company. This is one of the company’s first oil delivery trucks, parked in front of the home of I. W. Bagwell II, the company’s founder. (Courtesy of I. W. Bagwell IV.)

The Bagwell Oil Company was started in 1915, delivering oil to homes and businesses in the Onancock area. Originally the office was in the near side of this building, which housed a General Electric appliance dealership. (Courtesy of I. W. Bagwell IV.)

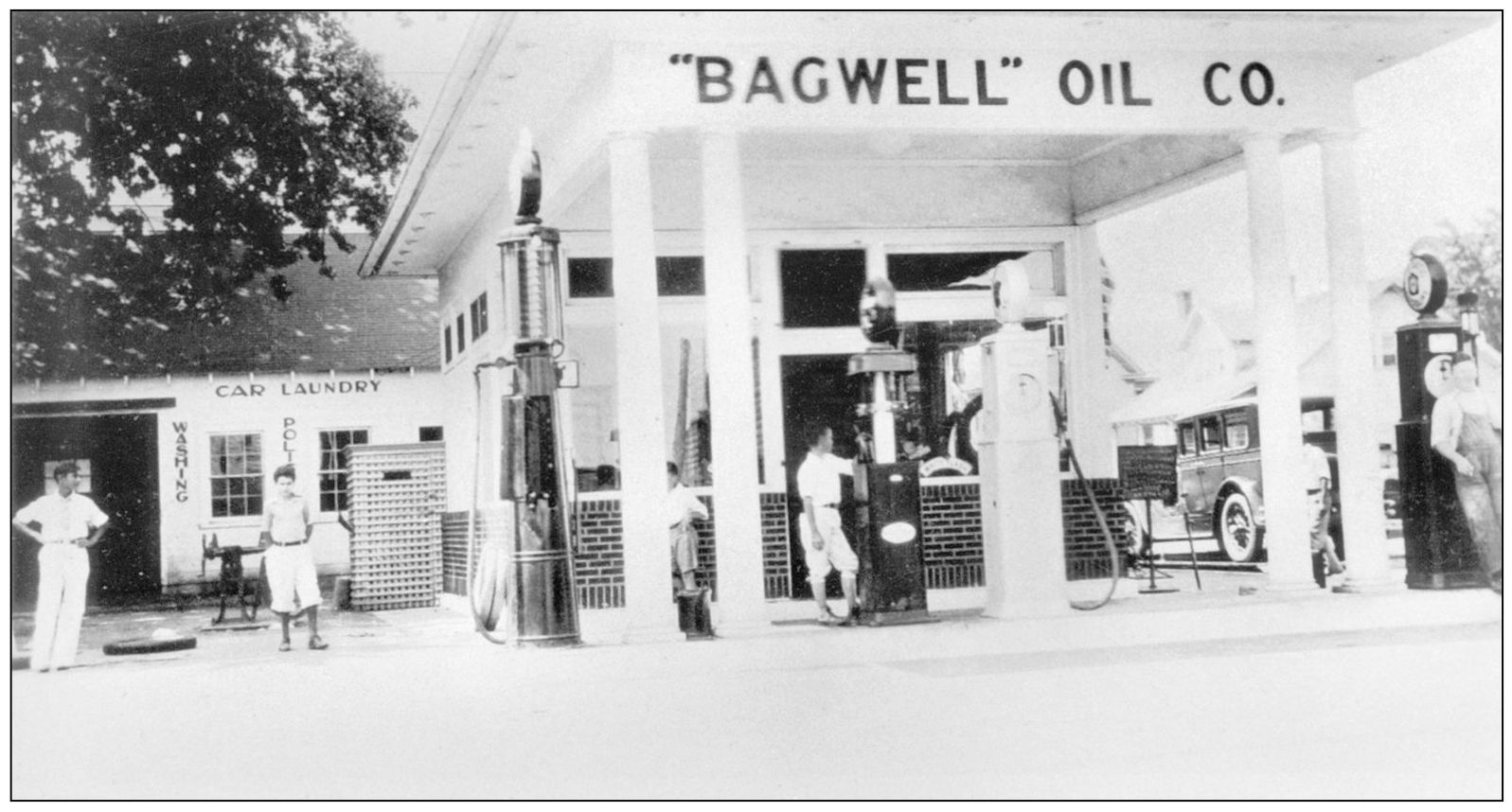

In addition to delivering heating oil, Bagwell opened one of the first service stations in Onancock. This one, which included a “car laundry,” was at the corner of Market and Hill Streets, where the Corner Mart convenience store is now located. (Courtesy of I. W. Bagwell IV.)

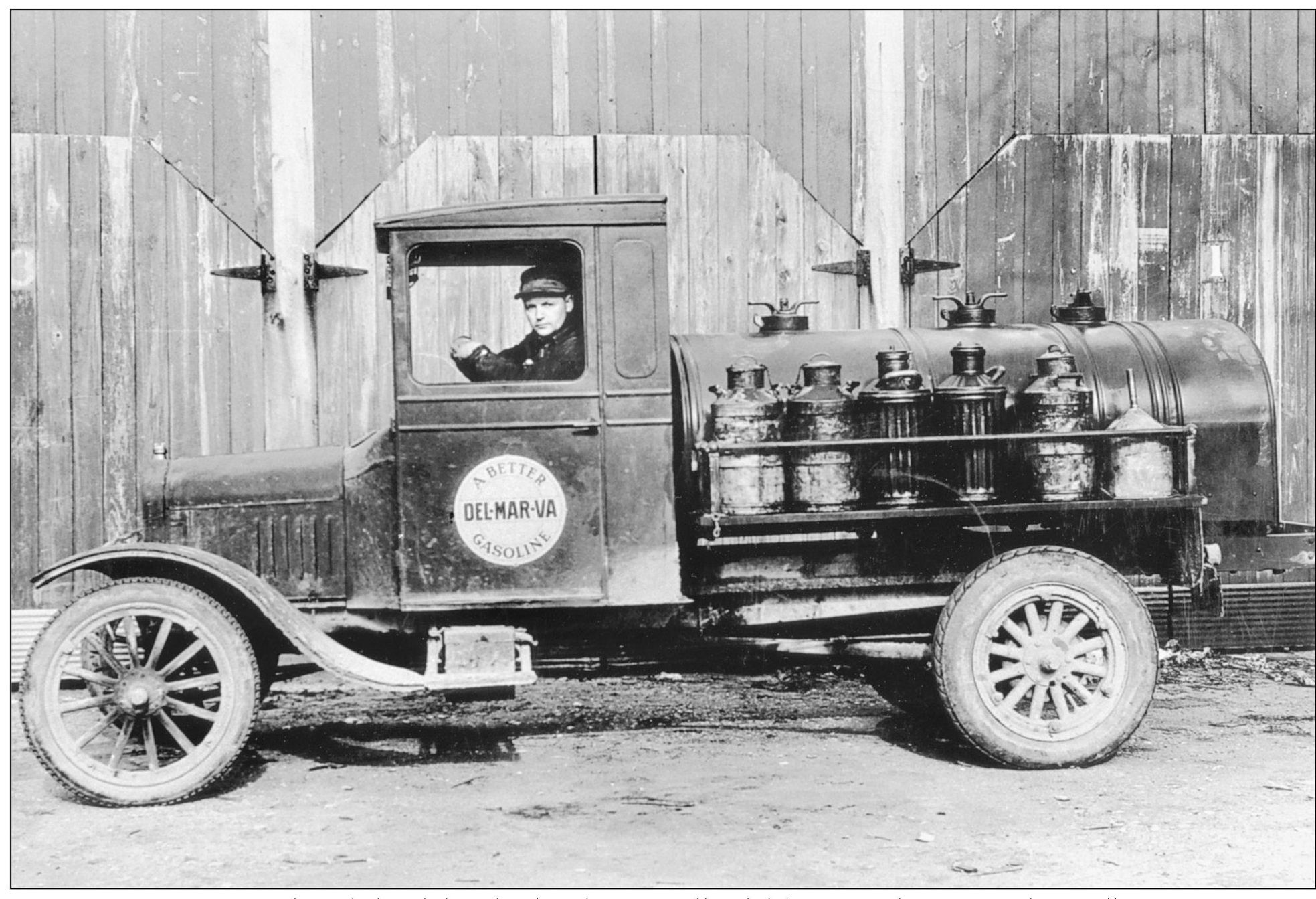

Cars were becoming popular in the early 1900s, and Bagwell began selling gasoline as well as oil. This 1922 Diamond T delivery truck held 633 gallons of BACO gasoline. (Courtesy of I. W. Bagwell IV.)

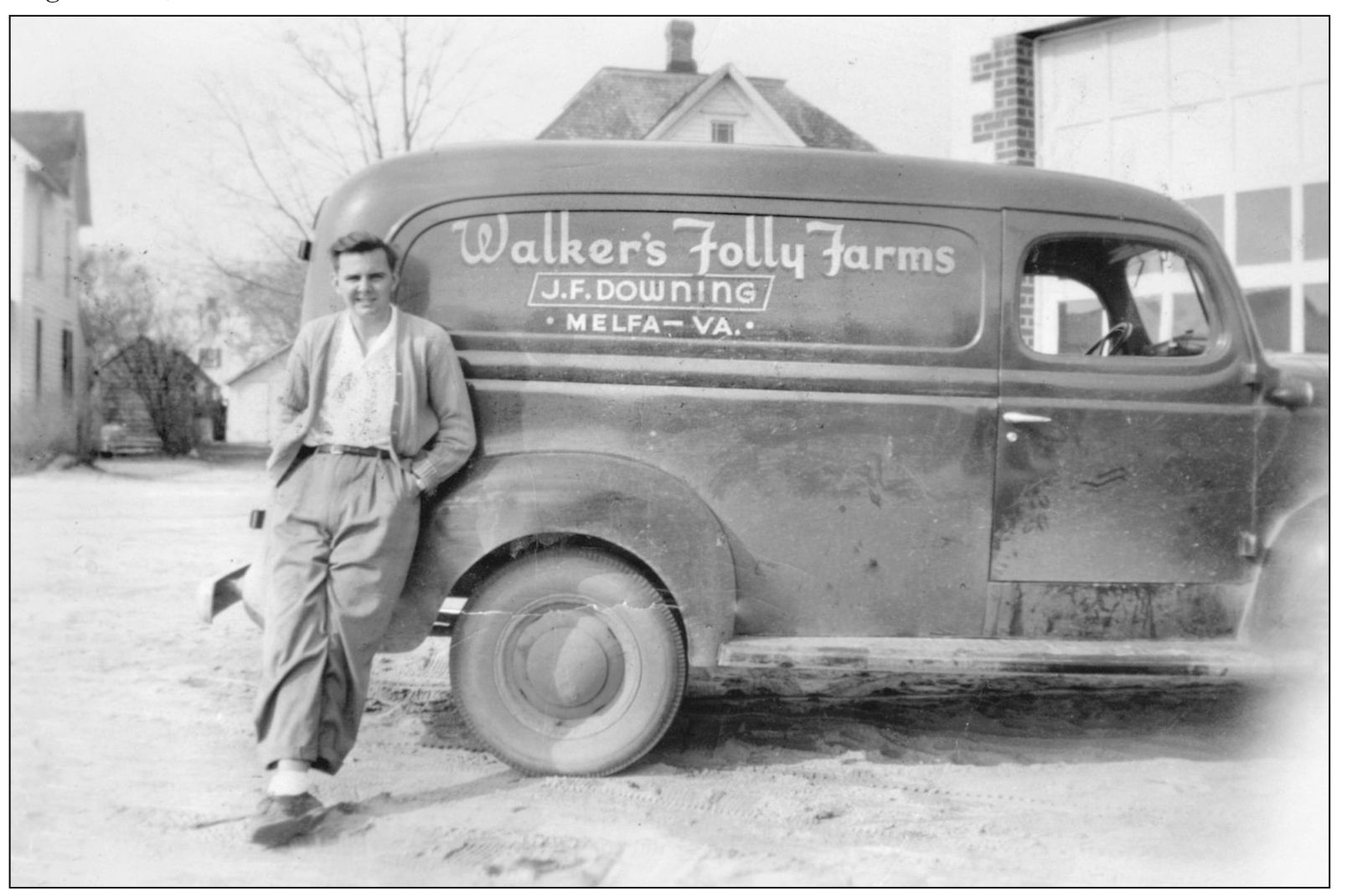

While gas and oil deliveries still are commonplace in Accomack, milk deliveries are not. Several communities had small dairies that bottled and delivered milk and other dairy products. The Nelson dairy was located on Liberty Street in Onancock and just south of Melfa was Walker’s Folly Farm. Dick Downing is shown here with the delivery van. (Courtesy of Jack Marsh.)

George Twyford was behind the wheel of this Bagwell Oil delivery truck in 1925. The small cans on the side of the truck were used to carry fuel from the truck to the delivery station if the truck could not reach it. (Courtesy of I. W. Bagwell IV.)

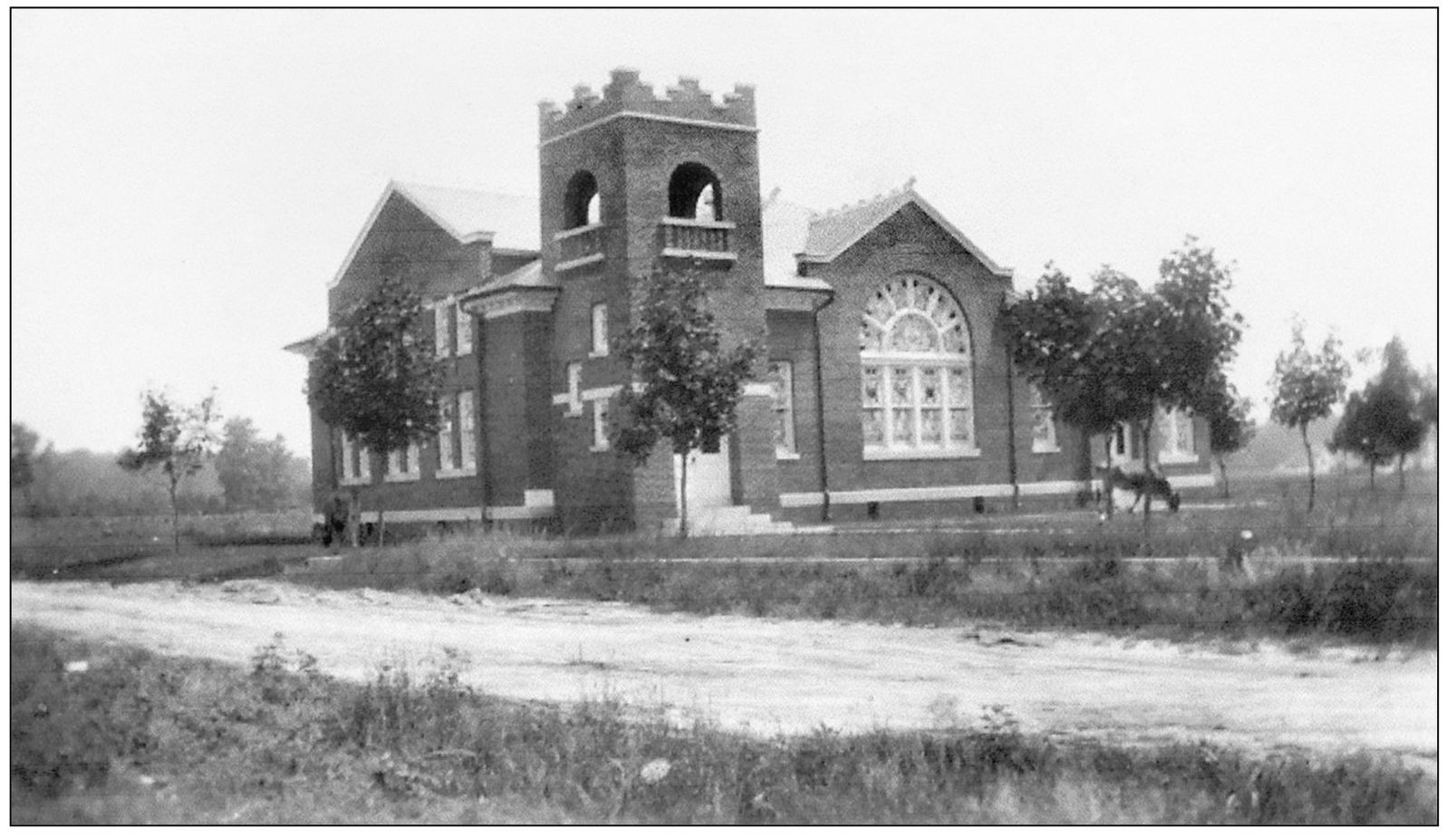

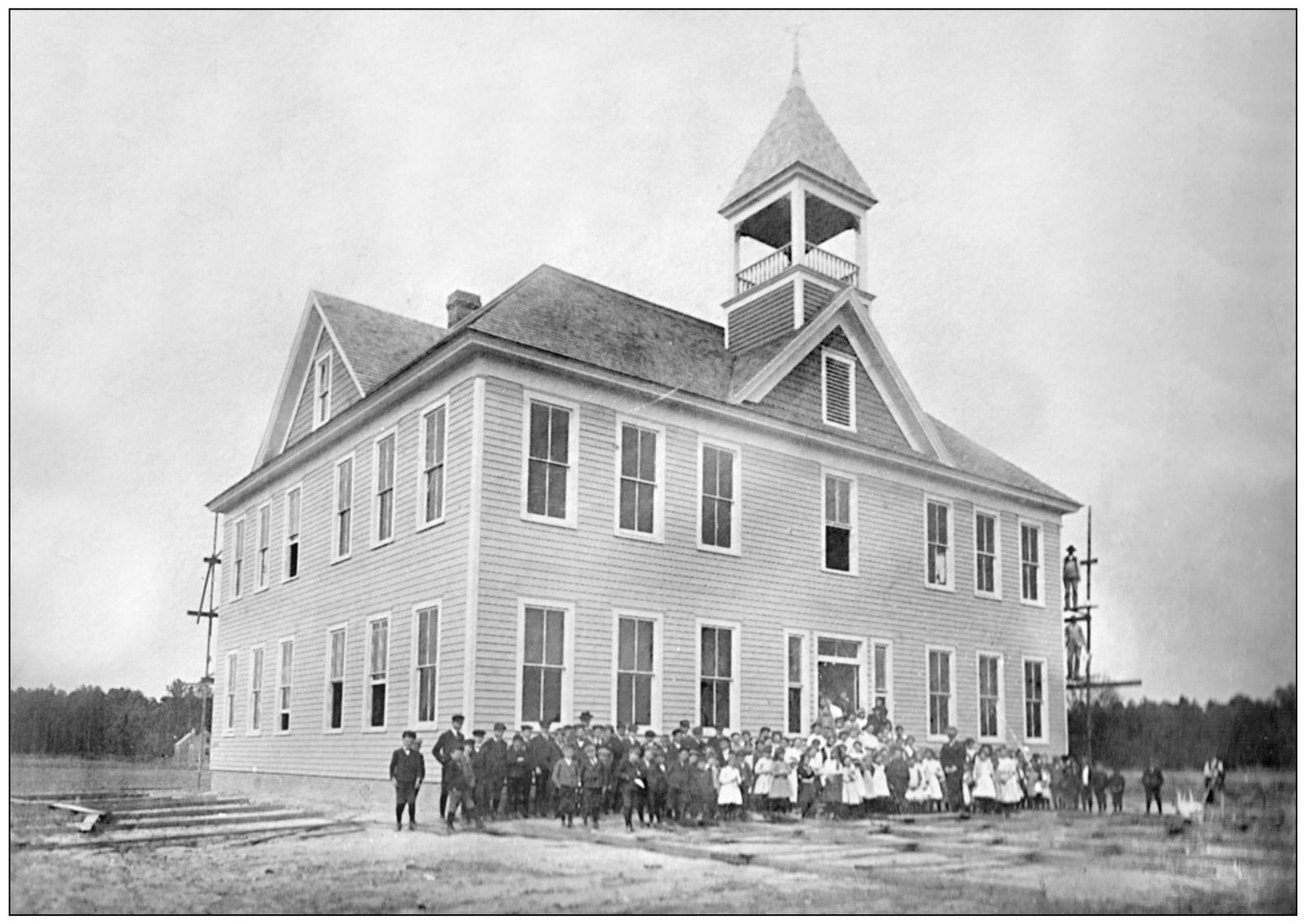

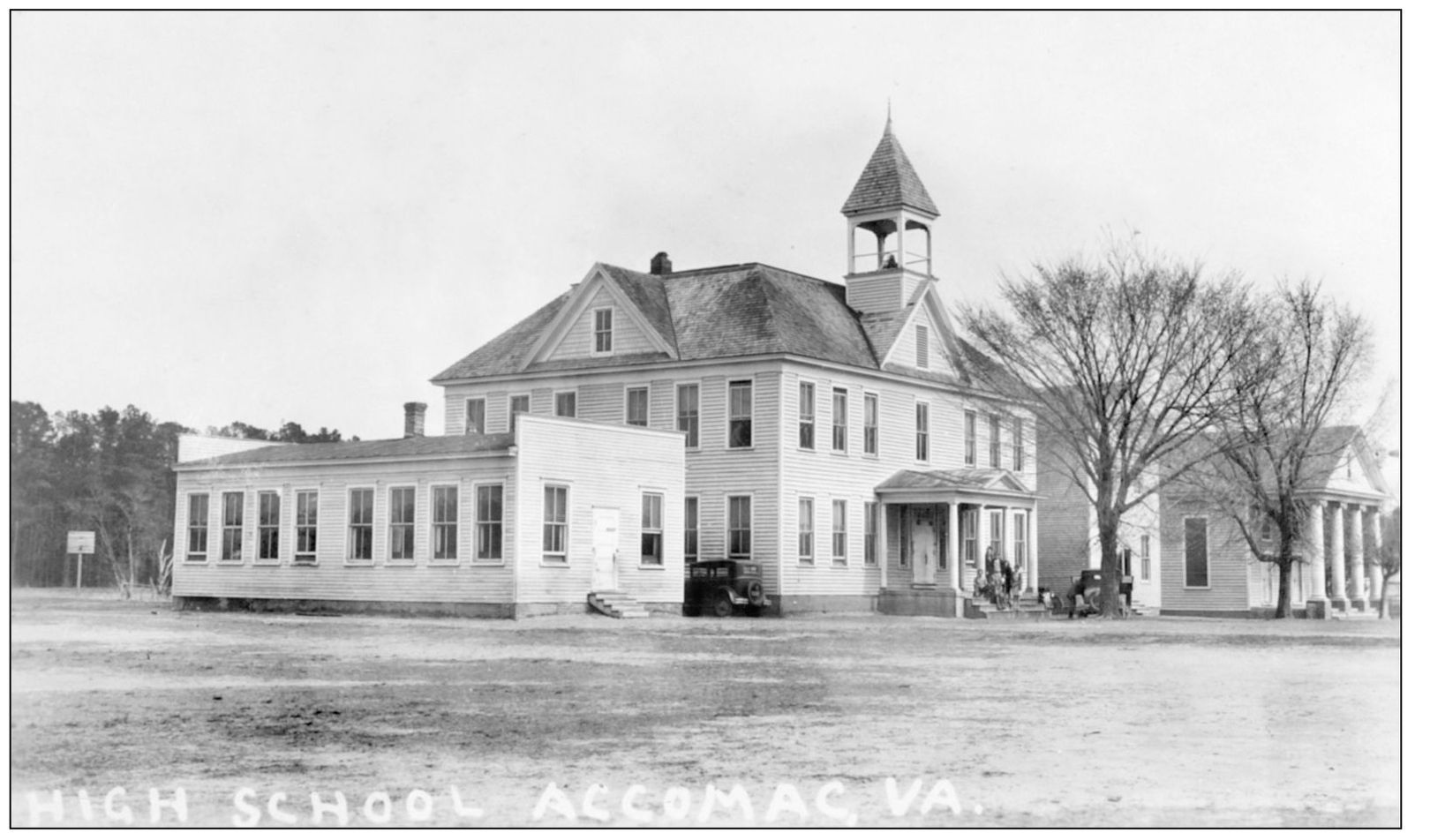

Accomac High School was just nearing completion in 1906 when this photograph was taken. Scaffolding can still be seen on the right side of the building. In 1912, the old Drummondtown Baptist Church was moved to the site and was used as a gymnasium and auditorium known as Bayly Memorial Hall. A brick school was built on the property in 1932. (Courtesy of ESPL.)

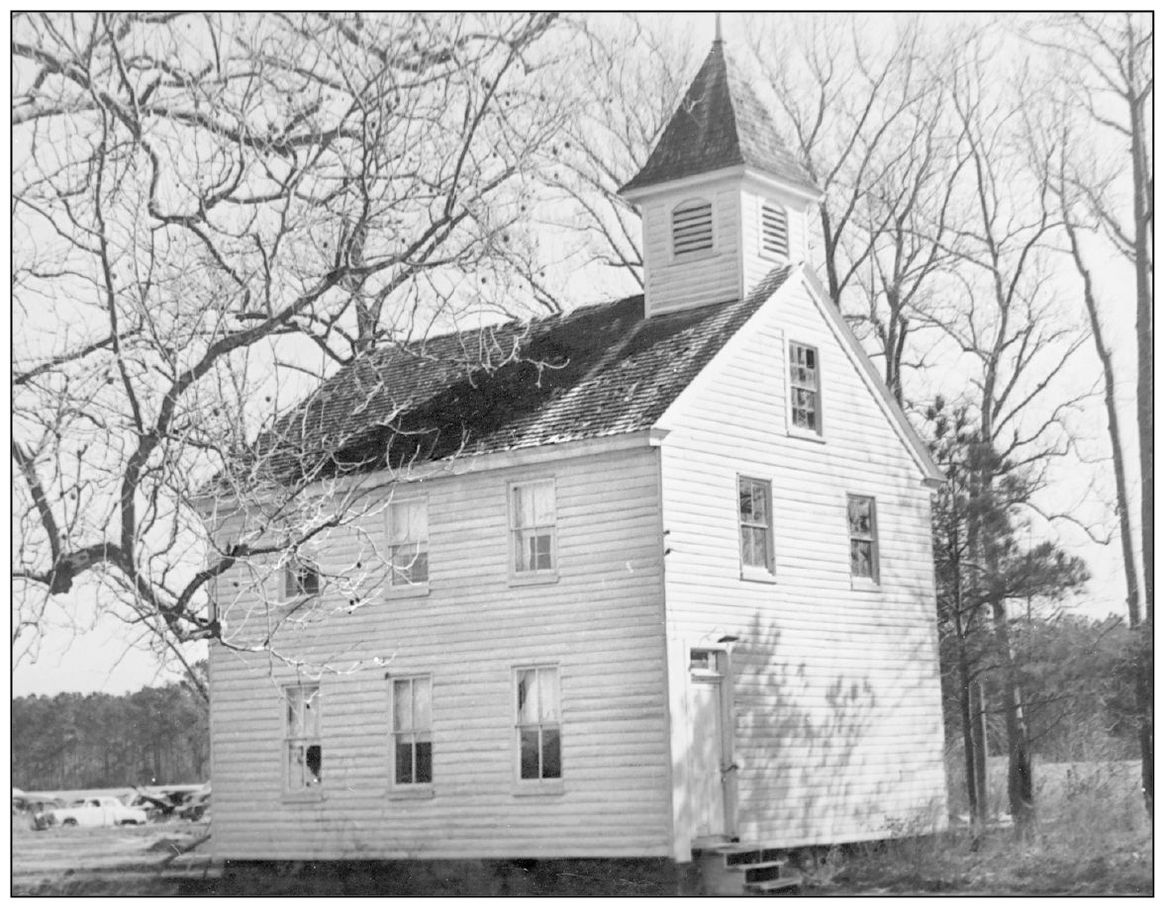

Accomack’s oldest school still standing is Locustville Academy, in the community of Locustville. In the late 1800s, education was very much a private affair in Accomack, with numerous academies and at least one college. Most schools in the county had only one teacher. The Locustville Academy was established by the Baptist church. (Robertson Collection, courtesy of ESVHS.)

Onancock High School was built in 1921 on the site of the old Margaret Academy and the Atlantic Female Institute, which existed prior to the Civil War. The Margaret Academy was originally near Pungoteague and was moved to Onancock in 1893. Onancock High School merged with Central High School to create Nandua High, and the building was used for numerous purposes over the years. It currently is used for community activities, arts, and other public events. (Robertson Collection, courtesy of ESVHS.)

In the early 1900s, Onancock High School had a corps of cadets that trained on the school grounds. The school, then located on Kerr Street, had three teachers and 119 students in 1900. The brick high school on College Avenue replaced the Kerr Street school in 1921. Dr. John Robertson, then a cadet, is fourth from the left. (Courtesy of ESVHS.)

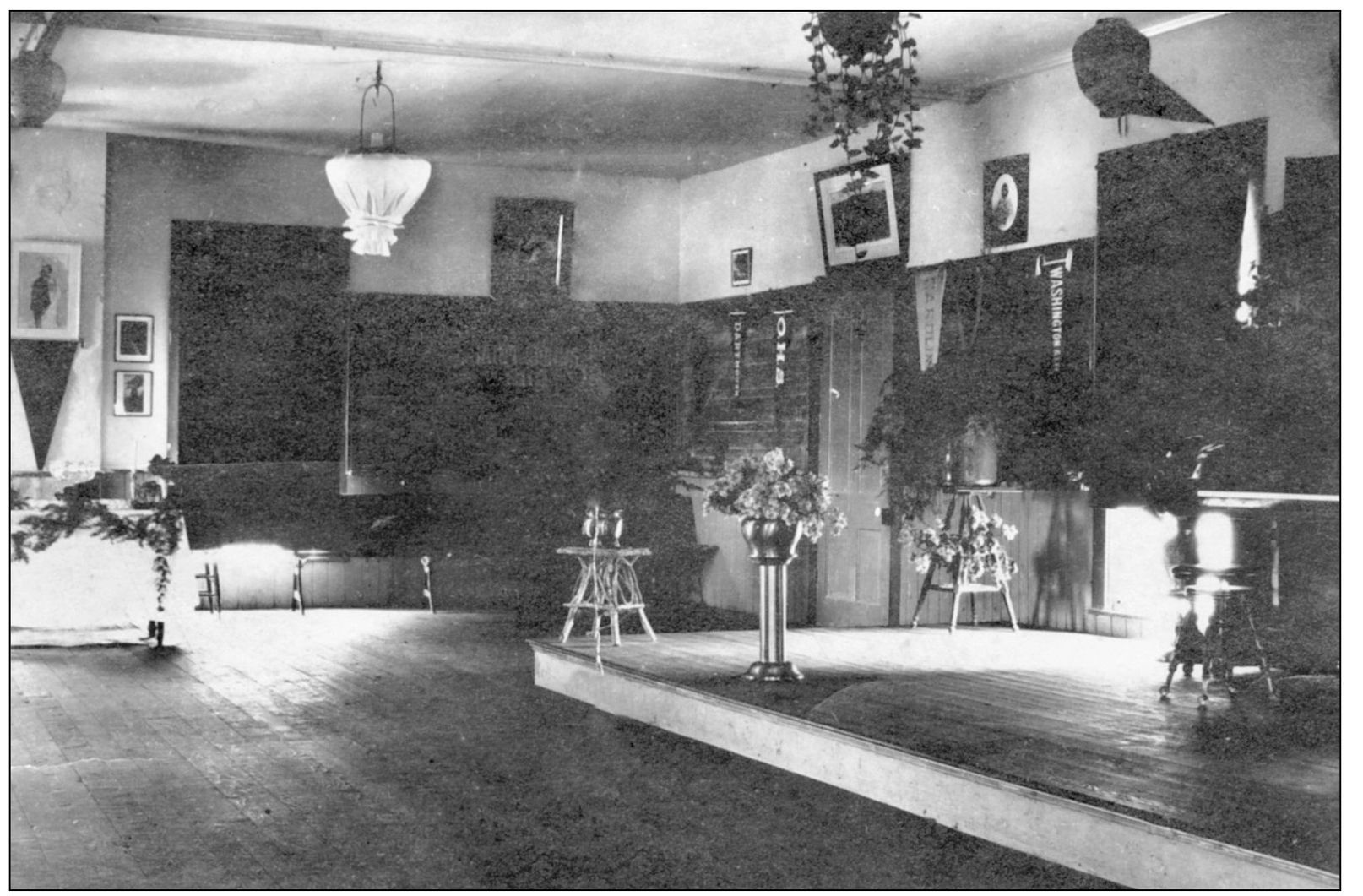

This is the interior of Onancock High School in 1911 in a photograph by Dr. John Robertson. The school had grown considerably during the first decade of the 20th century and at this point was offering a two-year teacher training program. Seniors helped with students in the lower grades and upon graduation received a teaching certificate. (Courtesy of ESVHS.)

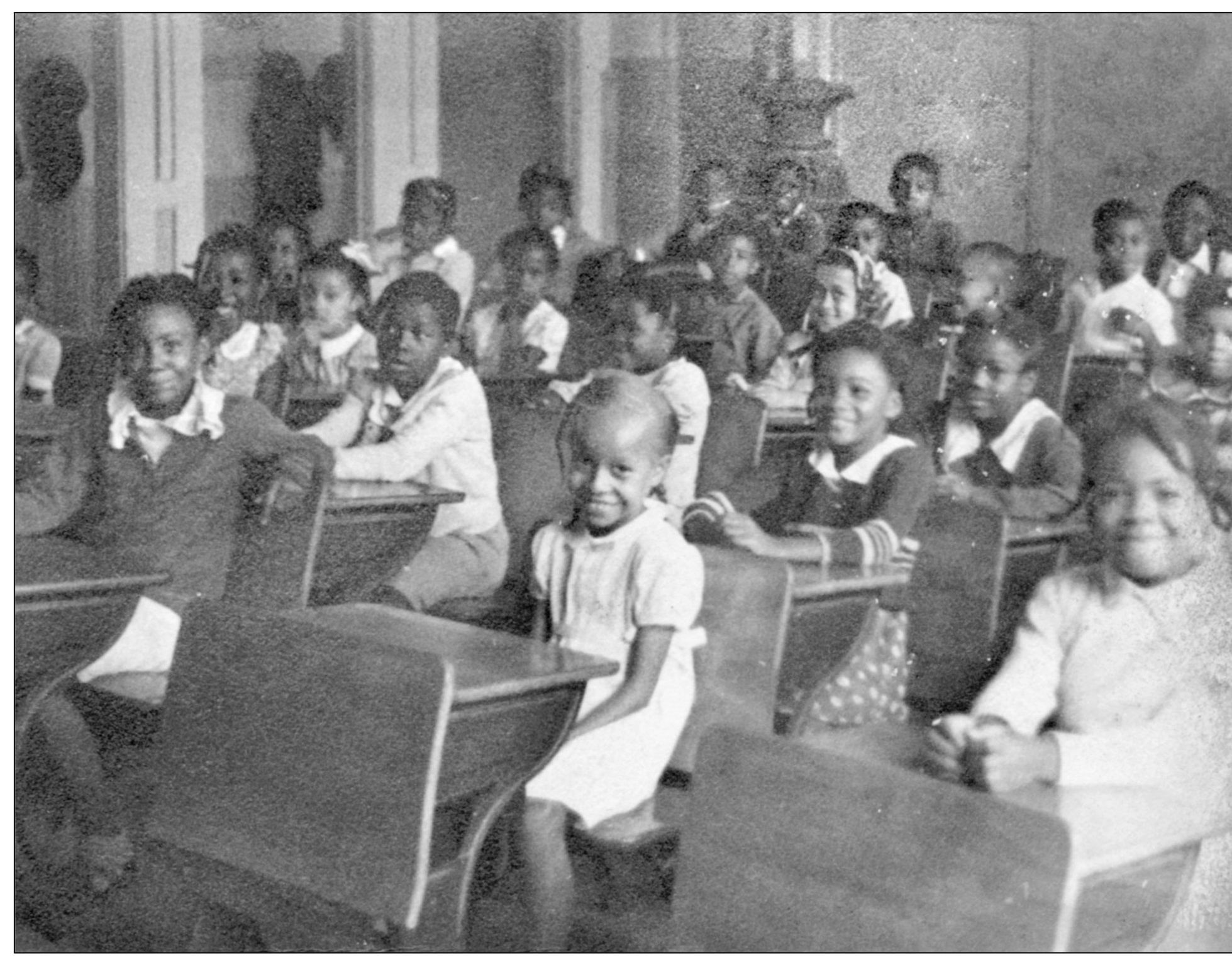

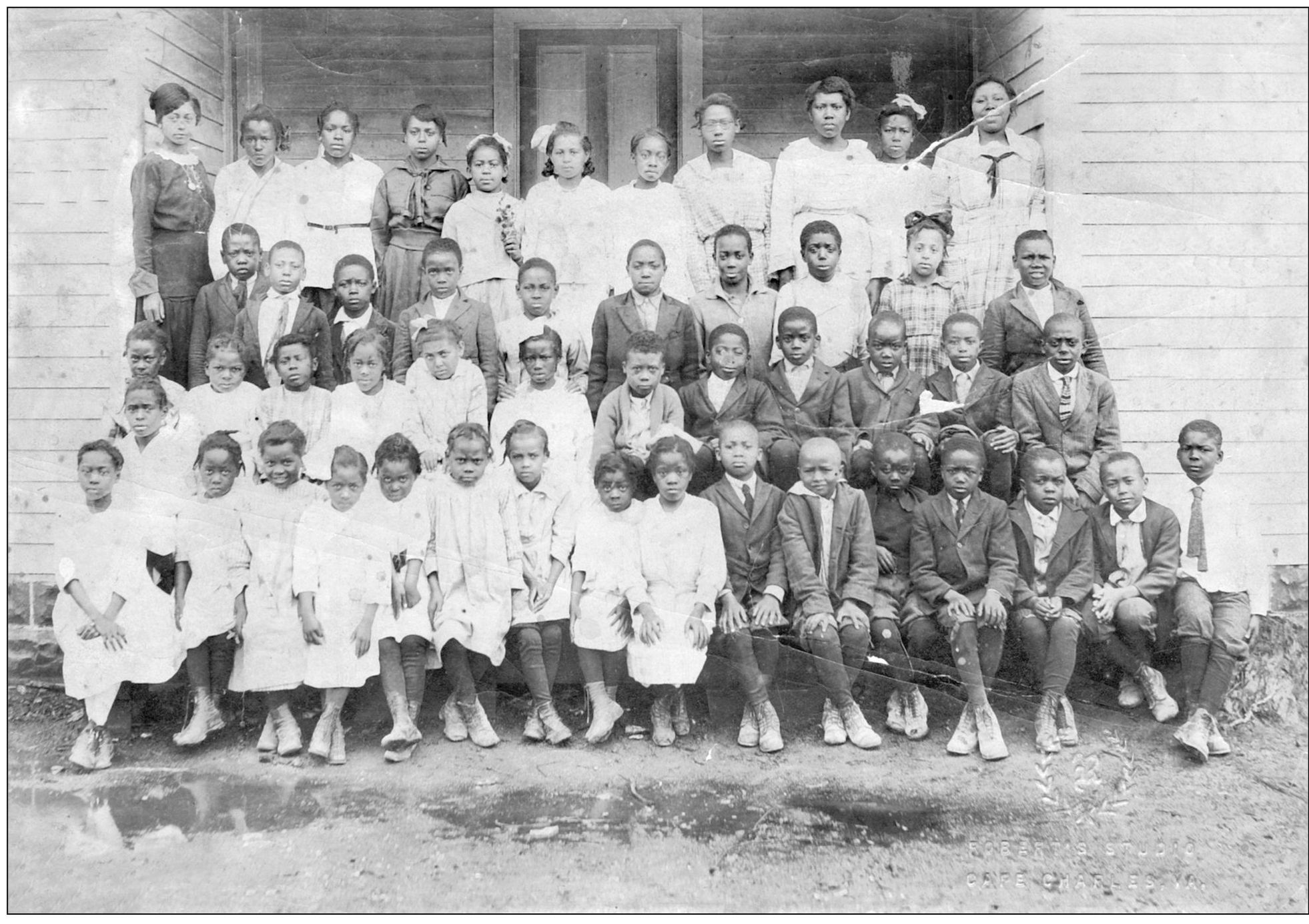

Black students from the Onancock area attended elementary school in a two-room building on the east side of town near the present Bethel AME Church. In 1933, a larger high school opened when the Mary Nottingham Smith School was completed in Accomac. In 1953, a new black high school opened on U.S. Route 13 north of Accomac, inheriting the original school name. In 1965, Freedom of Choice legislation made public schools available to all races. (Robertson Collection, courtesy of ESVHS.)

Accomac School had students from elementary through high school in 1920. High school students were in the two-story central portion, and elementary classes were in the buildings that flank it. The gymnasium can be seen at the far right. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

Onancock High School marked the dedication of its Normal School in 1905. The Normal School provided college-level teacher training, allowing older students to do internships to earn certificates. The men in hats were school board members, and the gentleman in the derby on the far left was Dr. E. W. Robertson, father of Dr. John Robertson, the photographer. (Courtesy of ESVHS.)

Accomac had a smaller public school for African Americans prior to the opening of the Mary Nottingham Smith School. The school was built by the county on land donated by Frazier Wharton around 1921. This photograph was taken in the mid-1920s. (Courtesy of Richard H. Allen.)

World War II brought years of rationing and sacrifice in Accomack County. Sugar, coffee, and canned goods were hard to come by, and residents were encouraged to “share the meat” in a government program that urged civilians to reduce their meat consumption so American soldiers and Allies could have more. Clothing and shoes were scarce in local stores, and silk and nylon hose disappeared altogether. But it did not take long for things to get back to normal once the war ended. In December 1946, pork was again on the menu. This hog killing was held at the Accomack County Jail, with seven large hogs slaughtered under the supervision of the sheriff, E. P. Parks, in the center of the photograph wearing the dark coat and hat. (Courtesy of O. W. Mears.)

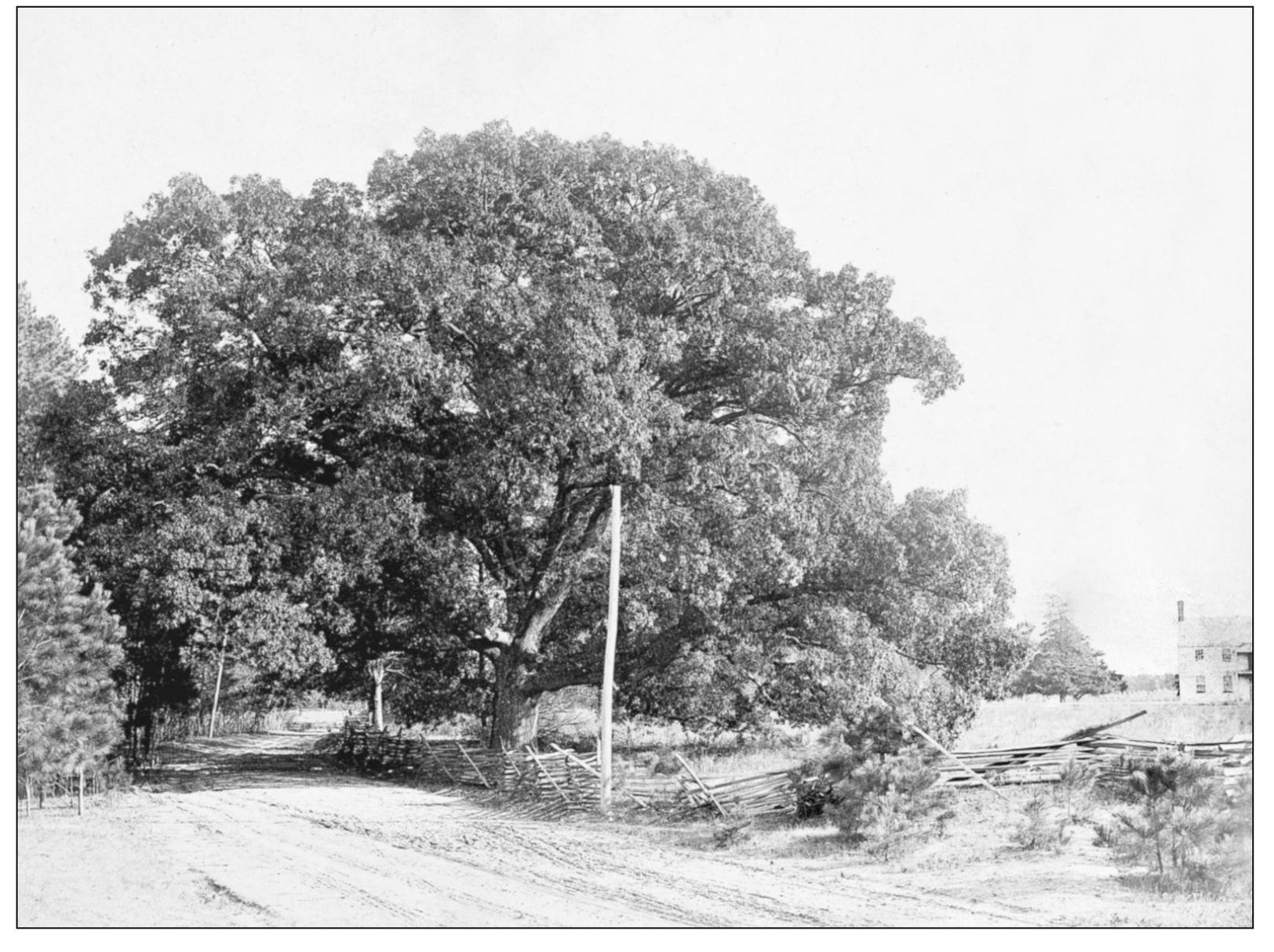

For many years, Maryland had less stringent marriage laws than Virginia, so young couples from Virginia would often elope to Maryland for a brief but binding marriage ceremony. In 1895, this “marriage oak” was a popular site for nuptials. A Maryland preacher lived nearby and could be depended upon for a quick service. The Maryland-Virginia boundary stone is in the background on the left. (Callahan Collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

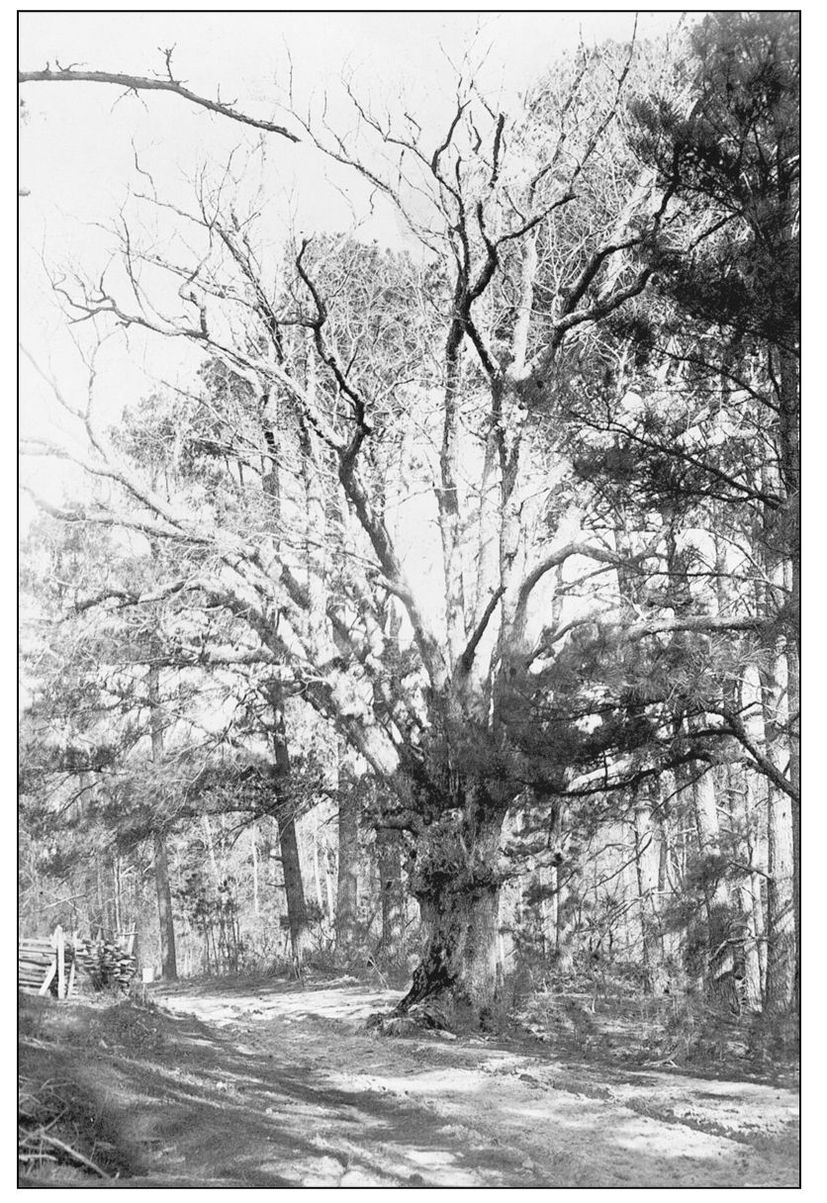

For many years, this oak was the largest tree on the Eastern Shore. It was on the Holly Brook farm, owned by the George Rogers family, between Pungoteague and Keller. This photograph was taken around 1900, and the tree lasted another three or more decades, finally being downed by a storm in the late 1930s. (Callahan Collection, courtesy of ESPL.)

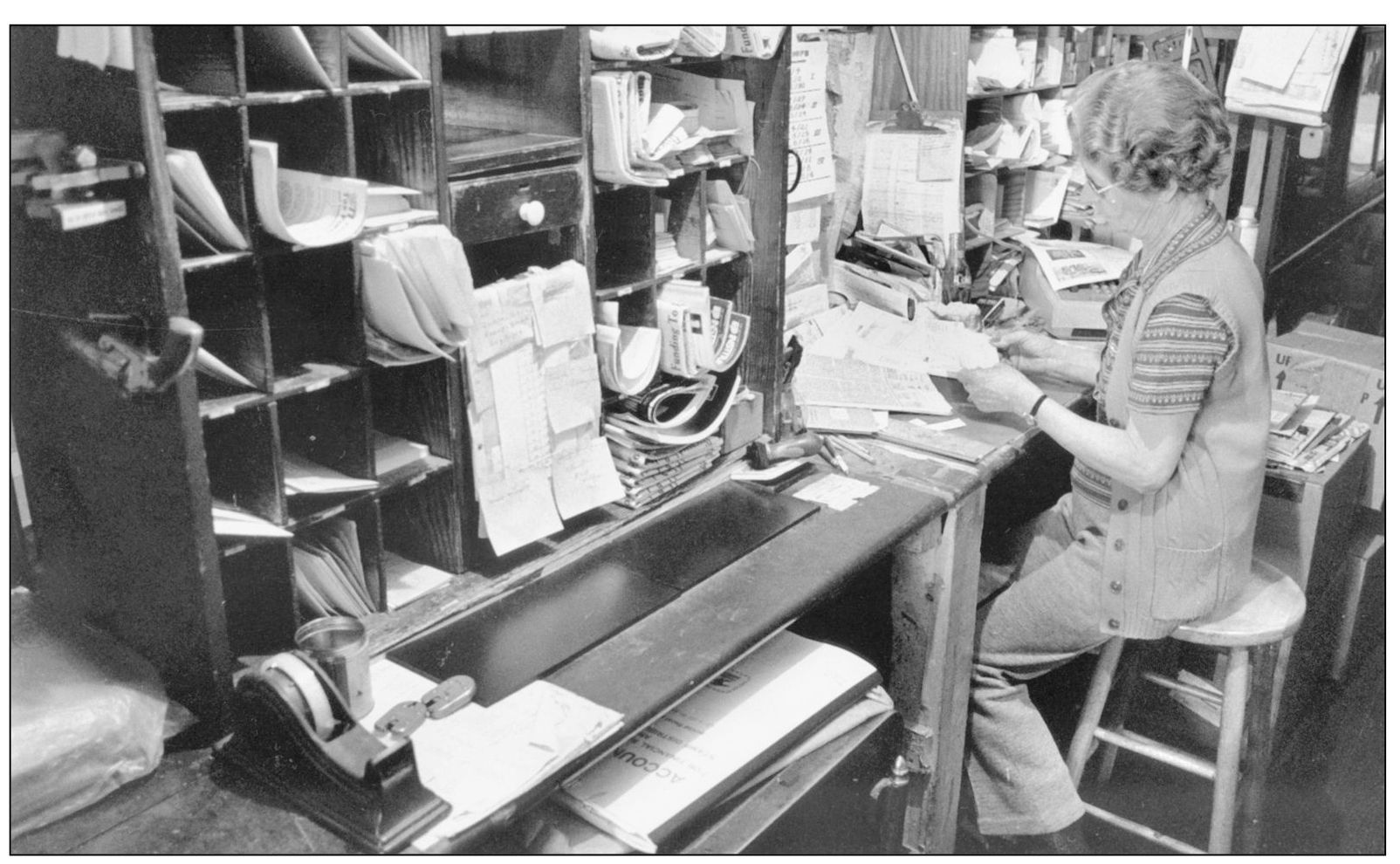

Country stores were a way of life in Accomack for many generations, and most have now disappeared. Country stores sold the daily necessities of life, including a quick lunch of bologna and sharp cheese, but they were also gathering places where local folks would catch up on the news. Many also served as post offices. Here Edna Milliner sorted mail at her family’s store in Locustville. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

Milliner’s Store in Locustville survived until the late 1970s, and it had several owners after that. As of this writing, the store is vacant. But not long ago, the shelves were well stocked, and a customer could pick up a good 5¢ cigar. Here Bill Groton waits on a customer in the mid-1970s. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

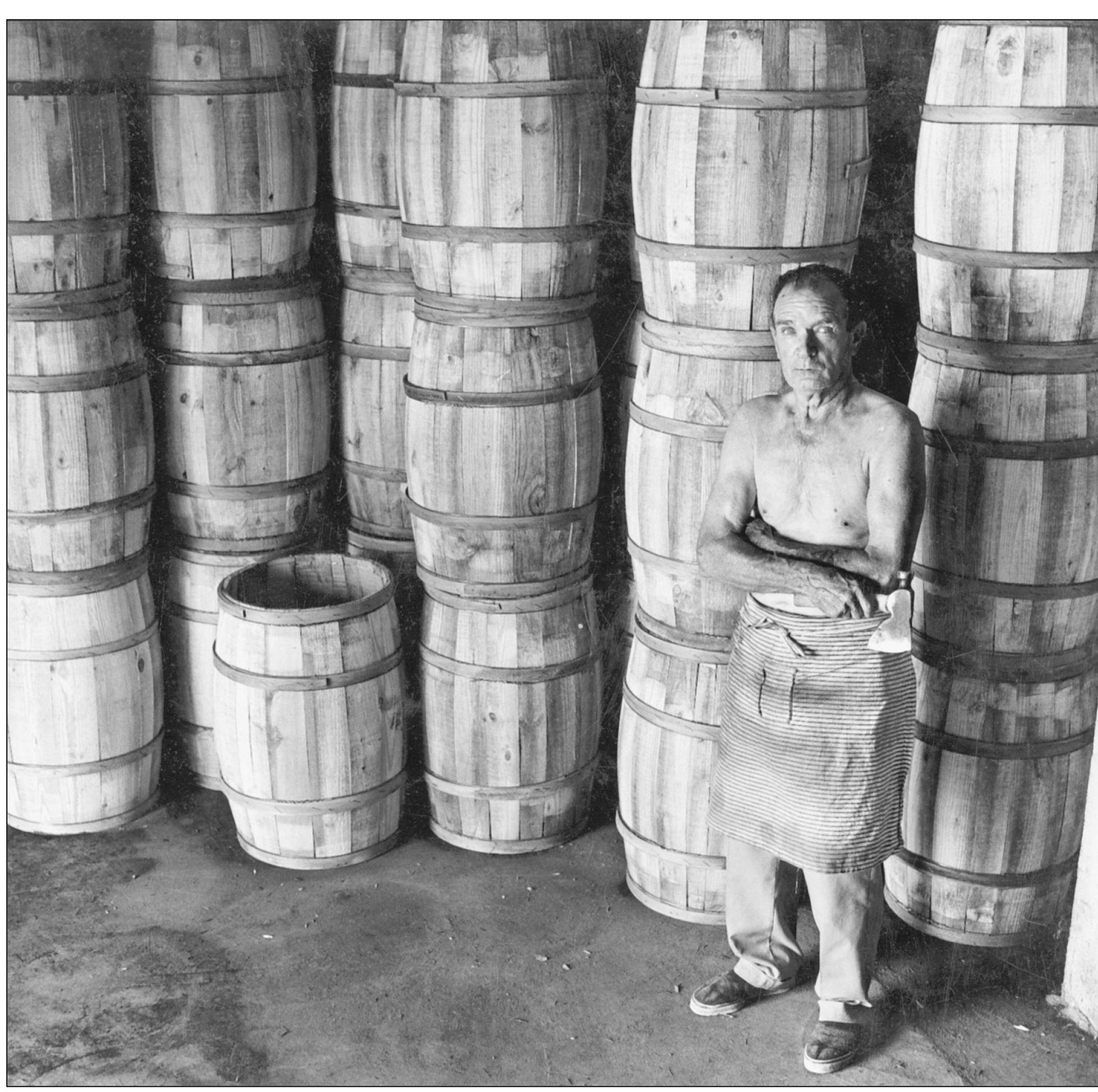

By the mid-1900s, barrel making was becoming a disappearing craft in Accomack County. Shippers began using bags for potatoes in the late 1920s, and baskets were used for crops such as green beans and tomatoes. The last full-time barrel factory was in Atlantic, and the barrel cooper was Alton Matthews, who made barrels for the Marshall Manufacturing Company. He was 65 when this picture was taken in 1972, and he was still turning out 110 to 125 barrels a day. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)

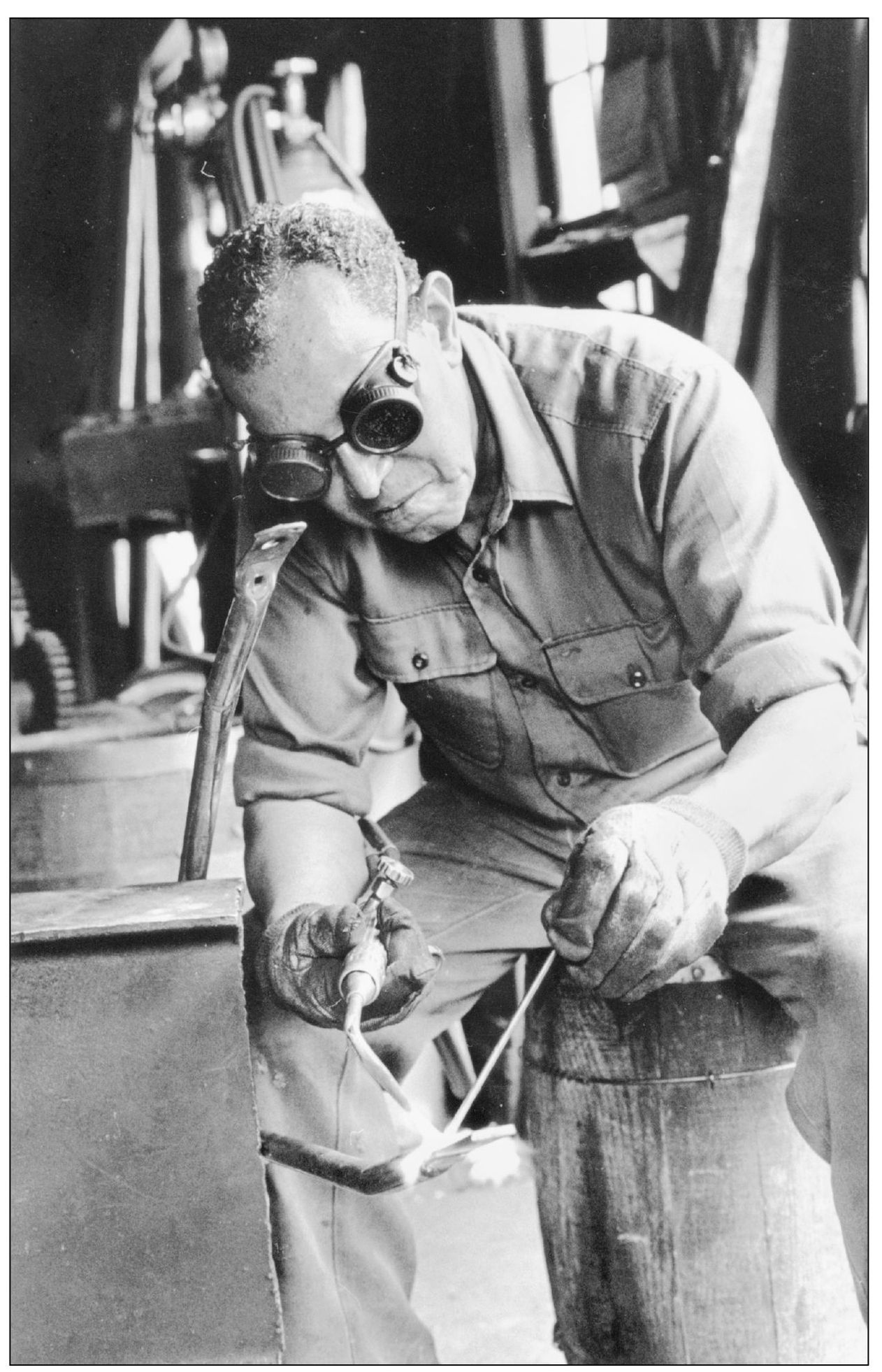

Samuel T. Outlaw was a well-known resident of Onancock for many years. A native of Windsor, North Carolina, he was born in 1899 and attended what now is Hampton University, graduating with the class of 1925. He came to the Eastern Shore in 1926 and began a blacksmith shop on Boundary Avenue. He worked as a farrier and did metalwork on strawberry wagons when local farmers depended upon horse power, and later he did a wide variety of welding and metal repair work. Projects ranged from boat rudders and crab scrapes to fabrication and repair of farm and garden equipment. He was the last full-time blacksmith in Accomack County and was a prominent member of the community. He served as clerk of the Bethel AME Church for 46 years and was Sunday school superintendent for 58 years. He passed away in 1994 at 95 years of age. His Boundary Avenue blacksmith shop is now a museum. (Courtesy of authors’ collection.)