On the morning of 30 April 1980 six Iraqi-backed Iranian revolutionaries assembled in the foyer of their hotel at 105 Lexham Gardens in Kensington, in London’s West End, and left the building en route to the Iranian Embassy in Princes Gate, South Kensington. They belonged to a group calling itself the Democratic Revolutionary Front for the Liberation of Arabistan, which sought independence for an oil-rich region in south-western Iran known officially as Khuzestan, whose inhabitants are ethnic Arabs, not Persians, with a history of revolt against Iran. By dint of its oil, Khuzestan is the source of Iran’s wealth, having been developed by British and American companies before and during the Shah’s reign, which ended with the Islamic revolution in early 1979. At that time the country was exporting five million barrels of Khuzestani oil a day – about one-tenth of the world’s oil production. Without Khuzestan, Iran is incapable of being more than a minor power. Most of its Arab inhabitants call it ‘Arabistan’, a region that came into Persian hands by a territorial swap in 1847 by which the Ottoman Empire ceded it to Persia in exchange for part of Kurdistan (now Iraqi Kurdistan), since the Kurds were Sunni Muslims, like most Ottoman subjects, while Khuzestanis were Shi’a Muslims, like most Persians.

Notwithstanding their shared faith, Khuzestanis were not reconciled to Persian overlordship, and maintained until 1925 a degree of local autonomy under their own Arab sheiks. Thereafter, the Shah’s father, Reza Shah, began a campaign of suppression to stamp out their autonomy and resettle Persian speakers in the region. The Khuzestanis rebelled after World War II in a bid to link themselves with Iraq, but were put down, remaining in this state until 1978, when oil workers in Khuzestan went on strike and cut the flow of oil to Tehran, contributing decisively to the downfall of the Shah and the onset of the Islamic Revolution. Any hopes of self-rule were dashed by the new regime, however, for the Ayatollah had no desire to see the new Islamic state partitioned into ethnically homogeneous regions – with Persians still a dominant majority, but separated from the Kurds in the west, Turkish-speaking Azerbaijanis in the north-west, Baluchis in the south-east and Khuzestanis in the south-west. In frustration, the Khuzestanis began a campaign of violence and destruction, inflicting widespread damage to the oil industry of Iran and reducing exports considerably below a million barrels a day – an 80 per cent decline. Herein lay the motive behind those who seized the Iranian Embassy in London: an opportunity – with the full attention of the world’s media and London’s large Arab community – to publicize their cause, grab headlines and trumpet their grievances which were largely unknown to the Western public.

This was not to be achieved simply by holding hostage the diplomatic staff of the Iranian Embassy; it was a deliberate measure to give Tehran a taste of its own medicine, for it was the logical parallel to the Iranian takeover of the US Embassy in Tehran that had occurred the previous year. The seizure of the embassy in London led to Iran’s immediate condemnation of the act as a conspiracy involving Iraq, the CIA and MI6. Such a sweeping and unsubstantiated claim succeeded in further alienating the Islamic Republic in the eyes of the West, and thus played into the hands of the Khuzestani separatist cause. It did not succeed, nor did it lead to the release of the American hostages, which in any event was never its purpose, but it did widely publicize the terrorists’ cause, one of their principal objectives.

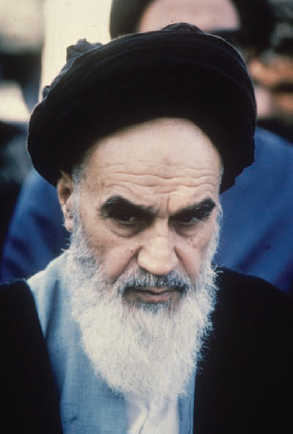

Yet the embassy siege cannot be fully appreciated without considering the broader context of Arab-Iranian relations, for the Arab world viewed the new regime in Tehran with suspicion and fear, regarding the Ayatollah as not merely a fervent defender of the Islamic faith, but a visionary on the edge – a mad reactionary seeking to return Iranian society and culture to the form it had originally taken in the 8th century, during the introduction of Islam to the Middle East, while simultaneously condemning Western values as satanic.

To his Arab neighbours, the Ayatollah represented a dangerous form of fanaticism and anarchy – a direct threat to their rule, especially the secular dictatorships like Iraq – not least because of his belief that clerics, including himself, should rule by divine right, a principle that rendered secular regimes hypocritical and illegitimate. No sooner had the revolution in Iran succeeded than clerics began a campaign of renewing Persian-Arab hostility, a feature of the region extending back more than a millennium, with the rift exacerbated by the fact that Iranians are largely Shi’as, whereas the ruling minority in Iraq were exclusively Sunnis. Iran’s revolution, like all radical political movements, was not intended simply to apply to a domestic context, but was to be exported, giving rise to grave concerns not merely in Iraq, but in Saudi Arabia, the Gulf States and elsewhere in the region. Nor were such anxieties without some foundation: from the outset, Iran openly condemned as false Muslims a number of neighbouring governments, saving the greatest vitriol for Iraq, which increasingly turned to whatever measures, including violence, it believed would curb Iranian missionary zeal.

Burning of the American flag on top of the US Embassy in Tehran, 4 November 1979. The Iranian Government erroneously believed that the attack on their own embassy in London six months later constituted a US-backed retaliatory operation using Khuzestani separatists to do their dirty work. (Corbis)

Relations between the two states had never been close, not least because Iraq’s predominantly Shi’a population was ruled – and traditional suppressed by – a Sunni minority under the ruthless Saddam Hussein, who was well aware that many Iraqi Shi’as looked to Iran for support. Nor is Iraq the exception: in Saudi Arabia, where Sunnis run the country, the rich oil-bearing region in the east of the country is Shi’a, and might conceivably have turned their allegiance to Khomeini. Bahrain, a tiny island-state in the Persian Gulf, is predominantly Shi’a, yet ruled by Sunni sheiks. Complicating matters still further, southern Iraq is the site of the holiest Shi’a cities – Najaf and Karbela – as significant to their respective populations as Jerusalem is to Jews and Rome is to Catholics. Indeed, for 15 years of his exile the Ayatollah lived in Najaf. To Iraq, therefore, if ancient religious ties bound Shi’as together more powerfully than did nationality – with the modern nation-states of the Middle East dating their existences no further back than the fall of the Ottoman Empire after World War I – Saddam could face a revolution himself, possibly backed by an Iranian regime which openly offered aid to fellow Shi’as. Having effectively governed Iraq since 1968, Saddam was not about to concede the reins of power to Shi’a nationalism, a revived Persian state and a volatile theocracy openly condemning secular modernism. Pride almost certainly played its part in this growing political and ideological rivalry, for Saddam regarded himself as the new Nasser of the Middle East, backed by $30 billion in annual oil revenue, an army of a quarter of a million men (as opposed to the grossly inefficient Iranian Army, whose officers had largely fled or been executed, not unlike the situation facing Royalist officers in France in the 1790s) and a leader with a Stalinist grip over his people. Such a leader was unlikely to permit a new challenger for regional hegemony, especially when Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and the other wealthy yet vulnerable Gulf States increasingly viewed Saddam – albeit with a degree of suspicion – as a bastion against Islamic extremism.

The Ayatollah Khomeini, political and religious leader of Iran, returned to his country from exile in February 1979. His government correctly deduced that Iraq lay behind the takeover of the Iranian Embassy in London, an act which contributed to the rapidly deteriorating relations between the two countries which would result in a bitter and appallingly costly eight-year conflict (1980-88). (Getty)

The denunciation of each other’s regimes was only the start of the growing rift between Tehran and Baghdad in 1979; soon, both sides began to call for the other’s overthrow, and trained and supported agents pursuing a policy of sabotage and assassination across the border, with the Iranians backing an ‘Islamic Liberation Army’ consisting of Shi’as from southern Iraq, and Saddam supporting calls for Khuzestani autonomy by sending armed men into the region to finance, train and equip its dissidents, and to blow up police stations, bridges and oil installations – all in a bid to erode the Ayatollah’s authority. Territorial jealousies did not end there, for Saddam also wished to recover control of the Shatt al-Arab, the vital 120-mile (192km) waterway formed by the confluence of the Tigris, Euphrates and the Iranian river Karum, which empties at the head of the Gulf at the Iraqi port of Basra.

The attack on the Iranian Embassy must therefore be seen in the context of the growing political tensions between Iran and Iraq between 1979 and 1980 that would later reach their climax in a bitter eight-year conflict, which began several months after the crisis at Princes Gate. In the meantime, the seizure of the embassy offered a high-profile method of striking at Iran in a city with lax security, a large, hopefully sympathetic Arab community, and an international press corps eager to televise events for the court of world public opinion.