7

She’s Ready for Her Comeback

It is 2013 (I’m now 41), and my partner wants to go to Stoke-on-Trent for the weekend to see something called the Staffordshire Hoard – the largest collection of Anglo-Saxon gold ever found. We arrive at the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery but it is closed because Tony Robinson from Time Team is making a television programme about it, so we are told to come back tomorrow. It is our first time in Stoke so we decide to wander around the town centre a bit and eventually happen upon a slightly run-down area that has optimistically been called the Cultural Quarter. There are a few shops and cafes. Then I see it – the words ‘Polari Lounge’ above a shop front. In my head, an angelic chorus starts playing.

‘What is this place?’ I ask in genuine, non-ironic, childlike wonderment.

We go in. It is an LGBT-friendly cafe which has opened recently, with council funding and, if I’ve remembered correctly, a donation provided by pop star and local lad Robbie Williams. There are pamphlets on the tables describing what Polari is – and my dictionary is listed as a source of information. I am swooning with excitement. This is impact with a capital I, the equivalent of the Holy Grail for increasingly harried twenty-first-century academics who are now required to justify their existence.

|

I go up to the counter and order two coffees. The young man, barely twenty, who serves me, doesn’t look at me. My default personality is shy but I want to talk to him. I’m so pleased. And I have so many questions.

‘This place!’ I say. ‘I did a PhD on Polari! I wrote a book about it!’

No response.

‘That’s me!’ I point at the leaflet.

‘That’s nice,’ says the man serving. ‘I’ll bring the coffees over when they’re ready.’

I go back to our table, deflated.

‘But that’s me!’ I say again. ‘This is my PhD come to life as a cafe!’

‘He probably didn’t think any of this up. It’s just a job for him,’ consoles my husband.

We drink our coffees and leave. I remember how in the 1990s, I never had trouble getting people to talk to me about Polari. I catch sight of my reflection on the way out and realize I am now middle-aged, and I announce this fact mournfully.

My husband says: ‘Look love, we’ve given up a weekend to see some bits of metal that someone’s dug up from a field. Of course you’re middle-aged. And I hate to be the one to tell you but you’ve been middle-aged for quite some time. I make it at least since 1997.’

About a year later I check and the Polari Lounge appears to have closed down. Maybe it was something related to their customer service training. Still, it is Stoke’s loss. And Polari’s.

When we last left Polari, at the end of the previous chapter, it was pretty much over. It isn’t going too far to say that Polari had virtually become a dead language. Perhaps that’s no big deal. It’s happened before and will happen again. People stop using languages and they die and are forgotten, or crop up in very restricted contexts. However, despite Polari reaching the end of its shelf life around the start of the 1970s, this wasn’t the end of the story. In fact, things were going to take an interesting turn after that point, with Polari undergoing not exactly a full revival but a revival of interest, resulting in various groups of people using it, in very different ways and for very different reasons compared to the original set of speakers. Some of the activities around Polari that I’ll relate in this chapter give me the distinct impression that that it’s gone on a rather different journey to many languages that undergo the process of language death. I don’t want to argue that Polari has been revived and is now flouncing around as a kind of camp zombie language, but rather that there’s become a kind of death cult around it. It is worshipped, there are myths that are told about it, there are rituals, and it even feels as if it is imbibed with the magical power to grant fame and fortune to a select few.

But let’s rewind a bit to the start of the 1990s when there were still pockets of people speaking Polari around the UK, many who are now of retirement age. Gradually, over the 1990s, life was starting to improve for gay people. The age of consent for gay male sexual intercourse was lowered from twenty-one to eighteen in 1994 (still not equal with heterosexual people – that wouldn’t come for another six years – but it is a step in the right direction). The discovery of combination therapies meant that the life expectancies of people who had HIV were greatly lengthened in many cases. Gay people slowly started to crop up more often in mainstream television and film, coming in a wider set of flavours. There were also a number of television programmes aimed at gay audiences. In the late 1980s, Channel 4 launched Out on Tuesday, a weekly rather highbrow documentary programme (later called Summer’s Out or Out), while BBC2 followed a few years later with the more populist GayTime TV. In 1999, Channel 4 broadcast a gay drama serial, Queer as Folk. The press started to be occasionally nice about gay people, or at least were not consistently horrible. Part of this change is the response to HIV-AIDS from within the gay community itself and the fact that the homophobic backlash of the previous decade prompted mobilization among those communities on a grand scale. Organizations like Stonewall, Outrage, the Terrence Higgins Trust and the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence were responsible for lobbying for changes to the law, taking the media to task for its homophobia and distributing information about HIV and safe sex. And this last group in particular were also at the vanguard of Polari’s rehabilitation, using it in a completely new way, challenging established thinking that camp was not political.

High Polari

The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, who we met earlier in the book, are another American import, being founded in the U.S. in the 1970s. Put simply, they are a loose-knit organization of men across several cities who dress as nuns. In the U.S. they were one of the first groups to mobilize in the fight against HIV-AIDS, handing out leaflets about safe sex in areas like the Castro in San Francisco. Their members can be viewed on several levels – as drag queens, as ministering to the spiritual needs of LGBT communities, or as political activists who wish to parody, question or reclaim traditional notions of ‘virtue’. During the last decades of the twentieth century some mainstream religious organizations had slightly softened their harsh views about LGBT people, preaching a message of loving the sinner but hating the sin – effectively disallowing gay relationships while trying to come across as inclusive and loving, a strategy also known as ‘having your (hateful) cake and eating it’. Notable exceptions to this rule included more accepting groups like the Metropolitan Community Church and the Quakers. Whether we believe in some form of higher power or not, religious organizations have, at times, provided people with a sense of social cohesion and a way of marking important life events with rituals around births, marriages and deaths. Gay people have often been excluded from such rituals or have had to hide their sexuality in order to participate in mainstream religion. On the other hand, with its emphasis on the physical, it’s possible to criticize some aspects of the gay subcultures of the twentieth century (and indeed the present) for downplaying spirituality. The Sisters therefore help to redress this imbalance for gay men by placing an overtly gay twist on religion – mocking and questioning the intolerance of mainstream religions while simultaneously creating a religious arena for gay men which is both tolerant of male-male desire and camp, and able to meet the different spiritual needs of individual gay men. By the 1990s, there were Orders in Canterbury, London, Manchester, Nottingham, Newcastle, Oxford and Scotland.

Same-sex relationships were not legally recognized in the UK in the 1990s, meaning that partners of loved ones would have no automatic inheritance rights, no visiting rights in hospitals and no say in how funerals should be conducted. The ceremonies carried out by the Sisters both pointed out this institutional homophobia and provided a framework by which LGBT people could celebrate or console one another at times of great joy or sadness. Their ceremonies included marriages and house blessings, and they also named notable LGBT figures as saints, including Harvey Milk, Peter Tatchell and Armistead Maupin. One such canonization was carried out on the film-maker Derek Jarman (unlike in Christianity, the Sisters sometimes canonized living people), with the ceremony conducted by ‘the Canterbury Coven’ at his home in Dungeness in 1991. An aspect of some of these ceremonies involves the use of what the sisters refer to as ‘High Polari’. One of the Sisters I interviewed had the following to say about the motivation behind Polari’s use:

Dolly [one of the Sisters] was concerned that because camp is unfashionable with the younger gays and radical queers, Polari would just be lost. The other motivation was that the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence were thinking of conducting their ceremonies in Polari, mirroring mass being conducted in Latin. Ultimately, we decided that having ceremonies that no one but the celebrants understood wasn’t helpful (just as the Church had done!). We do use a little Polari in ceremonies, for the exotic feel, but we’re careful to make sure people can get the meaning from context.

As a ‘dead language’, Polari is to gay men what Latin is to Catholics. Here’s an excerpt from the canonization of Derek Jarman:

Sissies and Omies and palonies of the Gathered Faithful, we’re now getting to the kernel, the nub, the very thrust of why we’re gathered here today at Derek’s bona bijou lattie. The reason being that Dezzie, bless his heart-face, is very dear to our heart. Look at him, his little lallies trembling with anticipation, heart of gold, feet of lead, and a knob of butter. So, perhaps we could take a little time to reach out and touch, to handle for a moment Dezzie’s collective parts.1

And the following is an excerpt of a blessing or prayer taken from a website (now closed) run by Sister Muriel of London:

May all our dolly Sisters & Brothers in the order receive multee orgasmic visitations from the spirit of Queer Power in 1998,

May you have multee guilt free charvering from now until ‘The Victory To Come’,

May our fight against homophobia and in-bred stigmatization bring forth a new millenium of love & freedom,

May our blessed Order Of Perpetual Indulgence continue to breed new and delicious acolytes across the world,

May we never forget our nearest & dearest who have been lost to us by HIV/AIDS,

May we not forget those who are living with it day by day,

May we as Sisters encourage all those with the fear of opening the closet door to have the courage to get their hands on that door-knob,

May we all continue to bring joy to the gathered faithful when we manifest together on the streets,

May Perpetual Indulgence always be our aim, and may the blessings of this beloved Celtic house be upon you and your happy parts now and forever.

Ahhhhh-men!

High Polari differs from the more informal versions of Polari spoken in private conversations or the scripted version spoken by Julian and Sandy, in that it occurs in a mock-ceremonial, sermonizing and ritualistic context. Despite this, it retains the same sense of camp and innuendo, although alongside this is a sense of celebration and pride, which suggests a more political stance. The sense of subversion of mainstream values and humour remains the same as in the old uses though. Ian Lucas writes that the Sisters’ use of Polari was

one of the structuring elements of the ceremony; it helped formalize responses between the Sister Celebrant and the Gathered Faithful. In this sense, it helped define the event itself. Responses were conditioned and directed through the formal use of Polari . . . For those members who were unsure about the sincerity of the canonization, the use of Polari offered a refuge, a semi-comprehensible sanctioning and mystifying of the Event.2

As mentioned earlier, the Polari dictionary sent to me by one of the Sisters contained lots of words that were taken from Cant, one of the earliest linguistic relatives of Polari, but it had little direct acknowledgement of the Polari words that were used by many of the speakers in the 1950s. Thus, although High Polari is a later instantiation of Polari, it actually contains words taken from much older sources.

The use of High Polari by the Sisters indicates there had been something of a turnaround in terms of the relationship that gay men had with camp in the post-liberation era. Andy Medhurst has described how rumours of the death of camp have been somewhat exaggerated:

Camp . . . was weaned on surviving disdain – she’s a tenacious old tigress of a discourse well versed in defending her corner. If decades of homophobic pressure had failed to defeat camp, what chance did a mere reorganization of subcultural priorities stand?3

And far from being apolitical, some campaigners for gay rights, reacting to inadequacies in political responses to the HIV-AIDS crisis, recognized and redeployed camp strategies in a political stance that was difficult to ignore by using equal amounts of humour and outrage to disseminate its message. A good example of this is the way in which camp was sometimes deployed at funerals of gay men who had died of HIV-AIDS, mixing outrage with celebration.

Perhaps we have to acknowledge the timing in Polari’s journey from being seen as silly, apolitical and even politically incorrect in the 1970s to its deployment in a serious political campaign in the 1990s. A lot had happened in the twenty years between these points, and there was now enough distance from Polari’s heyday for it no longer to arouse such a virulent sense of disapproval among this new crop of political activists. The Liberationists of the 1970s can come across as a little bit earnest – well-intentioned but keen to be taken seriously – and some wanted to distance themselves from aspects of gay culture that marked people as stereotypically gay. Part of this, I think, was due to growing up in a homophobic climate themselves, when camp, pathetic or villainous gay characters were the only representations available to them. But in rejecting Polari and camp, they were rejecting aspects of their culture, and it feels like a shame that they only saw the negatives. The next generation of gay activists viewed things a little differently. By now there was more of a sense of an established gay culture with its own history that was beginning to be properly documented. The testimonies of older people were starting to be taken seriously as opposed to the feeling that they had little to tell us and we needed to move on from them as quickly as possible.

On the throne: the Canterbury Covern of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence canonize Derek Jarman, Dungeness, 1991

And homophobia had not gone away after Gay Liberation. If anything, the lesson of the 1980s was that things were going to get worse for gay people, and the tragedy of HIV-AIDS, rather than giving those in power the chance to embrace and console, had simply unleashed knee-jerk moralizing, tabloid scorn and Section 28.

Camp enabled gay activists to rehabilitate aspects of their culture and history that had been sidelined – and, importantly, it injected a bit of much-needed fun and light-heartedness back into political activism. Just as the gay men of the 1950s had used Polari to laugh in the face of arrest, blackmail and bashing, the campaigners of the early 1990s incorporated Polari as a way of defying closed-minded politicians and showing that even in the shadow of HIV-AIDS it was possible to squeeze in a camp innuendo. Derek Jarman died of an AIDS-related illness in 1994, aged 52. During a time when there was considerable stigma around HIV-AIDS, Jarman’s canonization by the Sisters, including the touching of his ‘collective parts’, is indicative of a kindness and a desire to destigmatize that was sorely lacking in other quarters. And as always when Polari is used, there is that sense of the mocking of earnestness, the back-handed compliment, the toppling of the idol. Ian Lucas notes that

at the same time as Derek Jarman, as a person living with AIDS, was having his own body revered he was also the object of ridicule. He had become through the use of Polari in an irreligious manner, the site of the sacred and the profane. This was furthered by the Crowning of the Saint with a ‘bona helmet on his riah’ and a necklace made of cock-rings and pornographic pictures.4

Jarman took these aspects of the ceremony in his stride, though, and viewed his canonization as an important event in his life.

A slightly different view of Polari’s rehabilitation links to the notion of fashion cycles. In 1937, fashion historian James Laver devised a law which charted how attitudes towards a particular fashion change over time. For example, when something is ahead of fashion and yet to be adopted by the masses, it is often viewed as indecent, shameless or outré. Once it becomes fashionable it is seen as smart, but after that, attitudes start to become more negative. After one year it is dowdy, after ten years hideous, and after twenty years it is ridiculous. But then something interesting happens, and gradually the fashion is rediscovered and reappraised. At thirty years it is amusing, at fifty it is quaint, then it is charming at seventy, romantic at a hundred and beautiful at 150.5 We can’t fully apply Laver’s Law to Polari as I’m not sure that the exact numbers would work perfectly, but it has certainly gone through some of its earlier stages – smart in the 1950s, dowdy in the ’60s, hideous to ridiculous in the ’70s and ’80s. And by the 1990s it was on the way to being amusing.

Putting aside the reasons for the Sisters’ rehabilitation of Polari, they threw it a lifeline that was to have unexpected repercussions and ensure that it would never be truly forgotten. Later I’ll discuss how the Sisters’ use of Polari inspired projects by artists and members of more established churches (the latter resulting in your actual controversy), but for now I’ll pick up a different thread – one which sees Derek Jarman’s canonization being taken note of by academics and queer theorists.

An academic pursuit

Around the start of the 1990s, the concept of queer theory became popular within academic and activist circles. It was part of a new ‘postmodern’ way of thinking which was often unfortunately expressed by academics who favoured an inaccessible, jargon-heavy writing style (much more difficult to decipher than Polari). This was a shame and also a bit of an own goal because one of the points of queer theory was to question the existence of fixed social hierarchies and shed light on the ways that certain types of people are kept down or excluded from power. But if you throw around a lot of big words and write in such a highfalutin way that most people can’t make sense of you, then you’re definitely going to be excluding a lot of people yourself.

That aside, a central aspect of queer theory was that gender is a kind of performance – and we get our lines and stage directions from the society and time period that we grow up in. So we learn how to behave as a man or a woman based upon copying other people around us and we also learn how to organize our sexuality into little boxes or categories based upon what society at a given point tells us are the acceptable boxes that exist. But over time and across cultures, these boxes and ways of being a man or woman can change. To an extent this seems to make good sense. We’ve seen in previous chapters how there were different categories or ‘boxes’ linked to men who had relations with other men. If we think about, say, the Mollies of the seventeenth century, or the queens and trade of the early twentieth century, and then go on to consider the clones of the 1970s or more recent categories like twink, bear or pansexual, we can see that there are different ways of categorizing men who have sex with other men, but they are not permanent identities and they are subject to what a society will condone at a given time. The point of queer theory, then, was to show (or ‘deconstruct’ in queer theory parlance) how these different boxes or identity categories came into being, sometimes through an analysis of a society’s history, laws and media. Queer theorists tended to have different goals to, say, the Gay Liberationists, because the latter were more about saying, ‘We are an identity, we exist and we want equality,’ while queer theorists were more likely to say, ‘These kinds of identities aren’t as fixed as we think, so nobody is “anything” really.’

It was within this academic climate that research into sexuality began to get seriously under way, which included the creation of a sub-field that concentrated on the relationship between language and sexuality. Although largely represented by American researchers who organized themselves around the term ‘Lavender Linguistics’, there were a few British studies during this period, some which discussed Polari. Ian Hancock was one of those who wrote about Polari early on from an academic perspective, although the chapter he published in 1984 focuses on it in relation to other British languages used by travellers, and not from a gay perspective.6 This was followed by Jonathon Green, who gave a brief overview in 1987, although it was not until 1994 that Leslie Cox and Richard Fay considered Polari as part of a broader examination of different ways that gay people used language.7 A few years later Ian Lucas looked more at Polari’s uses in the theatre, including its incorporation by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence.8 In addition, there was a growing body of research on gay and lesbian history, which also referenced Polari, usually considering less the words themselves and more how Polari enabled secrecy during oppressive times. While some histories featured gay men and lesbians who had lived extraordinary or high-profile lives, others were more concerned with the lives of ‘ordinary’ people and included testimonies of gay men and lesbians.9 These histories usually briefly referenced Polari alongside mention of the Julian and Sandy sketches. A television programme called ‘A Storm in a Teacup’, shown in 1993 as part of the Summer’s Out series, featured interviews with Polari speakers as well as three scripted conversations containing Polari, performed by actors and set on a London bus. The first one appears to take place in the Second World War and is between two sailors on shore leave, the second is between two women in the 1960s, while the third features two gay men in the 1970s, one who speaks Polari, the other who is critical of it, using the phrase ‘phallocentric discourse’ and bringing to mind the Gay Liberationists of the previous chapter.

In some quarters Polari still appeared to be thriving. In a Gay Times article from 1995, journalist Peter Burton made note of the language he heard while watching the parade at Manchester Mardi Gras: ‘almost everyone within hearing range is using Polari, the lost language of queens’. One drag queen is described as saying: ‘Varda the bona cartes on the homis on the leather float. I’ve left my homi at home. He’s not very social.’10

It was around this time that I came into the story. I doubt that I would seriously have considered basing a PhD thesis around Polari if it hadn’t been for this small amount of existing research on the topic. The 1990s were a kind of sweet spot for Polari, when research on sexuality was finally starting to be seen as a respectable subject within academia and there were still enough Polari speakers available for someone to be able to locate them. The books I published on Polari in the early 2000s helped to cement its respectability as an academic topic, and along with other academics, I gave various interviews in the media and wrote articles on Polari for newspapers, gay periodicals and websites. Particularly with the growth of the Internet during this period, it became easier to find information about Polari and for people who were interested in it to form networks or get in touch with others if they were writing an article and wanted to interview someone. As a marker of how acceptable gay topics had become to the mainstream media, in 2010 I was interviewed about Polari for a piece that went in The One Show, an early-evening magazine programme aimed at a family audience, broadcast on BBC1. The piece was filmed in a very glamorous and atmospheric cabaret bar called Madam Jojo’s in Soho. I’d already come into contact with the bar a few years earlier though, as you’ll discover.

Brand Polari

After 1967, the decriminalization of homosexuality enabled people to establish a legitimate business or living from being gay for the first time in the UK. Prior to this, as described earlier, private drinking clubs and informal gay bars had been risky to attend as patrons could be arrested en masse. After 1967, gay bars and clubs became reasonably popular in most UK towns, with larger cities having numerous outlets. Establishments that catered to gay and lesbian clientele were often in peripheral parts of town centres and could sometimes be clustered together, with the same street having a gay pub, nightclub, cafe or restaurant, shop or sauna. Terms like ‘gay village’ were sometimes used to refer to these larger configurations of commercial outlets, and communities grew up around them, playing host to charities, medical and counselling services and meeting places for hobby and sports groups. There were increasing numbers of magazines and newspapers aimed at gay men and lesbians, which usually contained adverts for their target audiences. These included holiday packages, life insurance, greeting cards, clothing, films, books and music. For much of the 1990s, the Internet was mainly the province of academics and the highly computer literate; gay people still mostly made contact with one another face to face in actual physical locations. They talked to one another. They didn’t use fake photographs to hide their identities, and they didn’t ‘block’ anyone they didn’t like the look of. It was indeed an amazing time.

To an extent, the legal establishment of a physical gay scene from the 1970s to the 1990s resulted in a commercialization of gay identity, perfectly in line with wider economic, social and political trends in Britain, which saw a move towards rewarding private enterprise, along with the notion of people exercising power through their spending choices. The lifestyle products marketed to gay and lesbian consumers not only helped to foster a sense of gay community and pride, but enabled the people involved in selling those products to make a living. However, advertising was often used in ways that ‘sold’ a somewhat narrow view of gay identity – with young, bare-chested, muscular, white, handsome, butch-looking men appearing in a wide range of adverts targeted at gay men for all manner of products. It was in this climate that Polari started cropping up in various commercial concerns. One way was simply as a kind of brand – a word from Polari would be used to name a product or venue. This would typically involve a gay bar or shop. In Brighton’s Kemptown (where I conducted a lot of my Polari research all those years ago), there was a gay-friendly cafe called Bona Foodie. In the Isle of Wight, a clothes shop was called Bona Togs, and don’t forget the short-lived Polari Lounge in Stoke. In Dublin, a gay pub called The George offers ‘Bona Polari’ on a sign above the windows. It wasn’t just pubs though. A dentist in Australia wrote to tell me that he had named his practice Polari:

I have two friends from Sydney, one of whom was ‘raised’ by drag queens when he first came out and they were the ones who first told me about the language. In fact, I liked the idea of a gay language so much that I decided to name my medical practice, catering largely to gay men and lesbians, Polari. You should see the looks I get when I actually explain to someone what it means.

Not all brands that used words from Polari were purely commercial ventures. There was a community theatre group in Manchester that went by the name of Vada, and a group aimed at providing support for older people in London called Polari. Here’s an excerpt from a leaflet by the latter:

The love that dared not speak its name. Polari . . . The organisation was set up in 1993, choosing the name Polari for its associations with older gay people. (Polari was used as a covert gay language before the decriminalisation of homosexuality in 1967) . . . Firstly: Polari is actively seeking the views of older lesbians and gay people on how they want to be represented. Secondly: Polari is noting these diverse views and identifying the gaps through which people ‘disappear’. Thirdly: Polari is producing leaflets about a range of social care and housing issues to different types of inquirers. Fourthly: Polari aims to encourage older lesbian and gay people to speak directly to housing and social care providers through a programme of education and training.

However, other appropriations of Polari – especially more recent ones – placed less emphasis on the gay community aspects that the language evoked and instead tried to position it as something that can enable you to be cool or chic, for a price. Indeed, there is now an online fashion brand called Polari, which sells a ‘Polari is Burning’ T-shirt containing a small ® (registered trademark) sign above the word Polari. The phrase is a riff on the title of the 1990 film Paris Is Burning, which documents drag queens living in New York City. It harks back to an older form of gay culture, but it is the U.S., not the UK, that is being referenced here, so there is a kind of transatlantic blending going on, a bit like the 1970s British clone who took his look from the streets of the Castro or West Hollywood.

At the time of writing the Polari fashion website contains slogans like dish the dirt, and no flies and varda that bona omi, and most of the clothes it sells are boldly emblazoned with the word Polari and are modelled by young, hip-looking twenty-somethings.11 Who knew that Polari could be so cool?

And in 2013, in the trend-setting area of Shoreditch, London, a restaurant called Hoi Polloi created a cocktail menu with Polari-named drinks, including the Bijou Basket (consisting of gin, ginger wine and rhubarb bitters), the Riah Shusher (rhubarb and vanilla Tapatio Blanco tequila mule), the Bona Hoofer (gin, spiced syrup and espresso) and Naff Clobber (Buffalo Trace, Benedictine and maple syrup). The cocktails were priced at around £9 each and were described in Metro newspaper in a column called ‘Trend Watch’, where the managing director of Hoi Polloi was quoted as saying that the concept came about because ‘the theatre of the dining room is a perfect foil for the extravagance and camp of Polari.’12

Madam Jojo’s in London’s Soho also incorporated Polari as part of its brand. The burlesque bar opened in the 1950s and was popular with both gay and straight patrons. In 2004, I was contacted by a public relations firm who had been appointed by the bar. They had the idea of reviving Polari by getting their waiters to use it on customers when they were serving. They had a problem, though: they didn’t have enough examples of Polari to revive it in this context, and they wanted me to provide some form of training in the language. So I dutifully created a kind of crash course in Polari, which was distributed among the waiters, enabling them to incorporate a set of words and phrases into their interactions with customers. The PR plan worked and as a result the Polari-speaking waiters of Madam Jojo’s found their way into the news, with the BBC News website covering the story. The club’s owner was described as saying that ‘by offering staff at Madam Jo Jo’s the option of learning and using Polari to refer to familiar aspects and objects of their works we are offering a fun, yet practical way of bridging any language gaps.’13 I’m not fully sure that any language gaps were being bridged because Polari wasn’t really getting that much use in 2004, but it was a nice idea to recreate a sense of a 1950s Soho experience and to keep Polari’s memory alive.

However, with the examples discussed in this section there is something a little different happening, in that Polari is being used as a way not just of providing gay people with a sense of cultural identity, history and pride, but of ensuring the survival of a commercial establishment, product or brand and, implicitly, the livelihoods of those who are associated with that brand. The Polari words used in these forms of branding help to mark the products as gay, but I also think that, considering Polari’s current standing in the fashion cycle, they give it a sense of cool credibility. It is amusing that in 1999 the London-based Boyz magazine was describing Polari as deeply uncool and something that was only credibly spoken in ‘farmland or the kind of town where a trip to Woolworths is seen as going posh’,14 but just a few years later it was more likely to be associated with London’s ‘in-set’ getting cocktail umbrellas caught in their facial hair. The wheels on Polari’s fashion cycle were spinning pretty quickly, especially once it was seen as having the potential to sell things. I ought to note that I’m not disapproving of anyone’s desire to make a living through selling some T-shirts or colourful drinks – we all have to do what we can to get by, after all. But it does show how what happened to Polari after its ‘death’ is in some ways just as interesting as how it was used when it was alive.

So Polari was first rediscovered by activists, then academics, and then artisans. But this isn’t the end of the story. Another group – artists – were also poised to take it up from the late 2000s onwards. And you’d better hold on to your sheitel, because this is where Polari finds itself in even odder territory.

Highbrow Polari

Even as early as the late 1980s, Polari had been used by writers and film-makers as a way of adding a sprinkle of authenticity to stories that were set in mid-century Britain and featured gay characters or themes. We have already encountered Michael Carson’s semi-autobiographical Sucking Sherbet Lemons, which features a Polari-speaking character called Andy who identifies as Andrea and uses words like vada and dinge.15 Another novel, Man’s World, written by Rupert Smith in 2010, combines timelines from the 1950s and 2000s in order to tell an interwoven story of gay Londoners, and includes bits of Polari speech. The 1998 Todd Haynes film Velvet Goldmine is set in the mid-1970s and contains a scene with two characters speaking in Polari, with subtitles appearing in the screen in English: ‘Ooo varda Mistress Bona! . . . Varda the omie-palone . . . A tart my dears, a tart in gildy clobber! . . . She won’t be home tonight.’ Another 1998 film, Love Is the Devil – a biopic of the artist Francis Bacon – also contains a small amount of Polari: ‘Oh do stop staring at Mr Knife and Mrs Fork George, the expression on your eke you’d think they’d been covered in poison. Oh try to relax. Give her another drink!’

As part of Polari’s burgeoning association with culture, history and literature, it was perhaps unsurprising to see it starting to appear in increasingly highbrow circles. A literary salon created by the author Paul Burston was named simply Polari. Starting in the upstairs room of a pub in Soho, it is currently based in the UK’s cultural heart – the South Bank Centre – and has been described by the Independent on Sunday as ‘London’s peerless gay literary salon’. The salon has hosted numerous popular contemporary authors who have written on gay themes, including Jake Arnott, Neil Bartlett, Stella Duffy, Patrick Gale, Philip Hensher, Will Self and Sarah Waters. There is an annual Polari book prize, which is awarded to the best debut books that explore the LGBT experience, and the salon itself has won awards. I am not sure that very much actual Polari gets spoken at the salon but as a word which means ‘language’ the moniker is fitting.

Polari is also the name of a slightly less well-known periodical of creative writing, based in Australia.16 Describing itself as a journal which ‘celebrates writing that addresses sexuality, sex and gender’, it works ‘contrary to the mainstream and revels in the margins’. Its website features pictures of literary figures such as Oscar Wilde, Gertrude Stein and Allen Ginsberg. As with the London-based literary salon, I don’t think Polari itself is used very much (if at all) in the Polari journal, but instead it is the association with a historic, secret, marginalized form of language that is evoked by the title. Finally, Polari was the name given to an online magazine which ran in the 2000s, created by Chris Bryant and Bryon Fear.17 I was involved in this and occasionally wrote columns for it – I recall how Chris told me at the launch that he wanted to provide a different kind of publishing outlet for gay people, something distinct from the many gay magazines and websites that were currently available, one that wasn’t commercialized and didn’t use sexy images as a quick way of getting people’s attention. He vowed that it would never feature a picture of a bare-chested man. Over the course of the magazine’s history it provided political commentary and articles on a wide range of cultural topics.

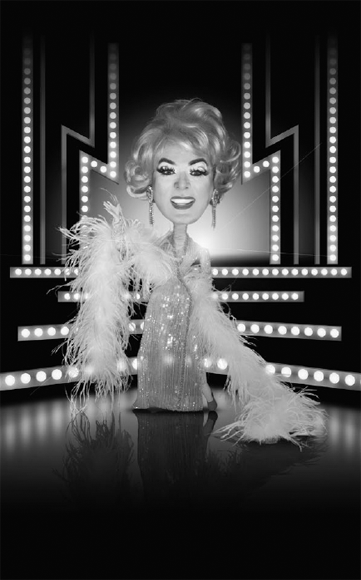

Uptown girl: Clementine the Living Fashion Doll

I attended the same launch event, which featured a short film that had been made by puppeteer and female impersonator Mark Mander. Mark has his own, original take on drag, having created a persona called Clementine the Living Fashion Doll. While Mark is British, Clementine has a heavily enunciated transatlantic accent, parodying the look and sound of glamorous movie stars like Joan Crawford. She consists of Mark’s head super-imposed on a tiny doll’s body – in his stage act, Clementine appears inside a booth, a bit like one used in a Punch and Judy show, with careful use of blacked-out clothing on a black background to hide Mark’s body and create the illusion of Clementine. However, Mark also creates animations with Clementine, and it was one of these films which was used at the Polari magazine launch, with Clementine finding out about Polari (the language), through the discovery of the Polari dictionary I had published, Fantabulosa. Clementine was thus the latest in a long line of performing drag queens to use Polari, but she did it in a more didactic way, teaching her audience about its history (while gently poking fun at me). Unlike some of the earlier Polari-speaking drag artistes who tended to be modelled on working-class housewives and performed in rough-and-ready pubs, Clementine is a much more upmarket queen, playing at venues like Crazy Coq’s, a beautiful Art Deco theatre space near Piccadilly Circus. Since the launch I’ve attended several of Clementine’s stage performances there and am occasionally called to the stage as a member of the audience to be ridiculed. I’d view Clementine as a postmodern drag artiste, providing not only a parody of femininity but a parody of drag queens themselves.

So, we have come rather a long way in a short space of time. From Polari being the province of ‘common’ queens who gave each other female names and chattered endlessly about the latest trade, to Polari being seen as a politically incorrect horror-show a couple of decades later, it is now moving in some of the most highbrow literary circles. I wonder what the Polari-speaking hairdressers, chorus boys and cruise-ship waiters of the 1950s would have made of its appearance in such rarefied company, or for that matter what the placard-holding Gay Liberationists of the 1970s would have thought of the rehabilitation of all this camp nonsense if they’d been transported to the present day in a time machine. I should stress that it’s not the language of Polari as such that has been rehabilitated and reclaimed, but more the idea of it. Still, I sometimes feel that Polari has whizzed from one social extreme to the other and now it’s just as marginalized as it ever was.

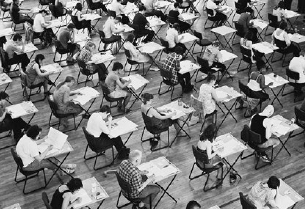

One of the most interesting illustrations of the recent cultural and artistic rehabilitation of Polari is from a loosely knit group of Manchester-based artists, including Elaine Brown, Joe Richardson and Jez Dolan. In 2010, I was contacted by Elaine and Joe, who were part of an arts organization called the Ultimate Holding Group. They had created a project called EXAM which had been commissioned as part of the Queer Up North Festival and involved a one-day public immersive art event. They explained that it was a kind of GCSE exam in LGBT studies. The exam paper was mocked up to look just like one from an official examining board, and the people who volunteered to sit the exam did so in a large hall under proper ‘exam conditions’ in complete silence with the examiner telling people to ‘turn their papers over’ and that they ‘may now begin’. The paper was marked and there was a results day when the volunteers found out how they had performed. The point of the EXAM project was to highlight how LGBT issues and people are usually absent from most aspects of the National Curriculum. Despite the repeal of Section 28 (in 2000 in Scotland and in 2003 in the rest of the UK), school textbooks still often feature ‘normative’ heterosexual families and tend not to give much space to topics like LGBT history, the persecution of LGBT people or the role they have played in furthering civilization. So the EXAM project aimed to address this by bringing LGBT people and issues to the forefront of education. The language portion of the exam was on Polari, which I thought was a nice touch, and Joe and I became friends, staying in contact in the ensuing years.

|

‘You may now turn over your papers and begin’: the EXAM project |

Later, Joe teamed up with Jez Dolan, who also happened to be one of the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence (Manchester branch), where he is called Sister Gypsy TV Filmstar. They received council funding to continue incorporating Polari into art projects, which resulted in a flourish of creativity in the following years. I played the role of linguistic adviser to these projects, although in fact I usually felt more like an art groupie, following them around their launches and being frequently amazed at their fresh perspective on what by now was for me the linguistic equivalent of a very comfortable pair of slippers.

One project involved hijacking Bury’s Festival of Light in 2012. Festivals of light are normally events that take place in winter evenings and are a kind of modern update on street parties or carnivals, designed to cheer people up on a miserable British November night. Bury is a small mill town in Greater Manchester which is known for black pudding and the Lancashire Fusiliers. During the Festival of Light, Joe and Jez used a projector to beam gigantic Polari phrases onto the outside walls of the Art Museum. As darkness fell over Bury, the words ‘He’s nada to vada in the larder’ loomed high above the heads of the meandering crowds of locals, and I saw a handsome dad mouth the phrase quietly to himself, shaking his head in mild consternation. Polari was certainly confounding the naffs on a grand scale all over again, although I wasn’t sure if I’d somehow missed the point (if this was another immersive art project, then who was it for?). The Art Museum also hosted a number of Polari-inspired pieces that Joe and Jez had made, including a ceramic dish onto which Joe had painted a pie chart. The chart displayed the percentages of words in Polari that were derived from different sources such as Cant, Back Slang and Cockney Rhyming Slang, taken from the Polari dictionary I’d published in 2002. The Polari definition of dish afforded the piece an additional pun.

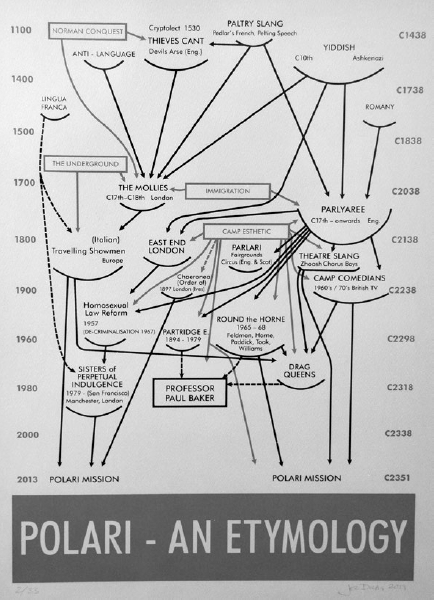

Jez came up with a different take on Polari’s etymologies by reworking a piece of existing artwork by Alfred H. Barr Jr called Cubism and Abstract Art, which aimed to map out the influences within different strands of art. Barr’s work is a complicated-looking diagram which shows links between different art schools like Neo-Impressionism and Cubism, and also has a timeline, so as you look from top to bottom you see how different fields in art come in and go out of fashion. Jez took the basic structure of Barr’s artwork, leaving in the boxes and lines, but changing all the labels so that they referred to the different influences on Polari over time (including many of the groups discussed earlier). Due to the fact that Jez couldn’t fiddle about with the existing diagram’s structure, this visual Polari etymology shouldn’t be taken as a perfect account of the language’s development, but I think he did a pretty good job of getting it as close as possible. But perhaps the group’s most ambitious project was the creation of the Polari Bible.

The Polari Bible was originally published online.18 It had been created by Tim Greening-Jackson (aka Sister Matic de Bachery), who used the Polari dictionary created by some of the other Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence as the basis of a computer program. This program converted an English version of the Bible into Polari. Jez had the text of the Polari Bible put into a huge, beautiful leatherbound book, and it was displayed in a glass case at the John Rylands Library in Manchester, alongside a range of important historic Bibles. The point of this was to highlight how religions are not very accepting of LGBT people but that they should be. Also, there was another level to it – about how powerful religious people get to decide what objects are sacred and which ones aren’t. So the Polari Bible was treated by the artists and the John Rylands Library as a sacred object; you aren’t even allowed to touch the thing without putting on a pair of very white gloves as the oils from your skin will damage the delicate paper – a nice touch of High Camp. Jez organized a number of public readings of the Polari Bible, described in more detail later.

As well as the art exhibits and the Bible, the Manchester artists also put on a play about Polari’s history, drawing on my books as source material. In fact, two plays about Polari took place in 2013, one written by Jez and his team, another by Chris of Polari magazine called In the Life: A History of Polari, starring Steve Nallon (who was famous for voicing Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s TV comedy series Spitting Image). The plays featured a mixture of music, dancing and acting, referencing the Round the Horne sketches, sailors, drag queens and trade. In the Life featured a scene where Melvyn Bragg interviewed Professor Peri Odical about Polari’s status as a language, resulting in a lot of pontificating about anti-languages and lexicons. As parodies go, I got off lightly, while the performer Champagne Charlie (Robbie Bonar, not the nineteenth-century Champagne Charlie) performed a number of songs, including a cover of ‘Bona Eke’. And around the same time, Polari went fully online, as Joe Richardson used the dictionary I’d published to create a phone app. One of the features of the app was that you could shake your phone and it would present you with a random word or phrase.

In 2015, two other artists, Brian and Karl, created a short film set on Hampstead Heath, called Putting on the Dish. The film involved a conversation on a park bench between two men, credited as Maureen and Roberta, and involved the most dense (and tense) use of Polari I’ve ever heard. Unlike the much earlier scripted version of Polari used by Julian and Sandy, the characters in Putting on the Dish don’t give the viewing audience an easy ride or provide translations as they go along. Their Polari comes thick and fast – kudos to the two actors (Steve Wickenden and Neil Chinneck), who speak it as if they’d known it their whole lives.

In the Life, featuring Champagne Charlie (Robbie Bonar), 2013

One aspect of this short film which I found interesting was how the speakers seamlessly incorporated the different etymological influences or layers of Polari into their conversation. There are words like bencove and chovey from Cant, as well as Parlyaree words like nanti and charver, backslang words like riah, Cockney Rhyming Slang words like kyber, Yiddish words like shyckle, basic French like mais oui and 1960s/1970s slang terms like remould. This is recognizably Polari, but there’s no way of knowing if the ‘everything but the kitchen sink’ version used by Maureen and Roberta would have been fully understood by twentieth-century speakers. From my interviews with Polari speakers, most of them tended to know a few core words and then used just as many terms that tended to be more limited to their immediate social circles. I also get the impression that as the decades passed, Polari gradually changed so that different words fell in and out of fashion at different points. The version of Polari used by Brian and Karl is similar to that found in the Polari Bible, in that it feels as though it has been influenced by the existence of dictionaries (including my own), which contain a good many of the known words of Polari taken from different points in time. As a result, these more scripted versions perhaps shouldn’t be seen as completely authentic re-creations of the language, but that’s not surprising – the ways that we represent the past are very much filtered through the lens of the present. I suspect that as time goes on, future attempts to re-create Polari may struggle to capture exactly how it was used.

Another nice example of a more contemporary repurposing of Polari was in a short book called Cruising for Lavs, written by George Reiner and Penny Burke (proceeds of the book were donated to the charity Lesbians and Gays Support the Migrants). The book follows a dialogue between the two authors, with George describing his life to Penny, as a young man growing up in Cornwall, then moving to London as a student. As with the Brian and Karl film, the authors of the book use Polari from a mix of earlier sources, as well as throwing in a few new terms:

I hear you ducky, strano is our way to do the rights. Girl, she’s bold, we may zhoosh our riah, flutter our ogle riahs, and ask for a deek from those glenn hoddles, you know at the same tick we’d be saying nish thank you, kiss my aris!19

It would miss the point to question the ‘authenticity’ of such modern texts – they are to be understood as coming from the voices of twenty-first-century speakers and are perfectly in keeping with the magpie-like way that Polari speakers mixed and matched words from different sources.

An unintended consequence of my research and publishing the dictionary is that I enabled Polari to be raised from the dead for brief moments, but sometimes I feel it is more like a kind of anachronistic Frankenstein’s monster version of the language. As linguists are trained to be dispassionate creatures, being more concerned with charting the ups and downs of a language as opposed to getting into debates about which way of using language is the ‘right’ one, I’m liable to simply see this new development in Polari’s story as an interesting turn of events rather than anything else. But others may think differently.

This chapter reveals that Polari managed to stay dead for only a few years before someone spilt a few drops of enchanted blood on it and it came back – not in its original form but in a different, ghostly way. It appeared in strange rituals spoken by men dressed in robes, it graced the cocktail menus of the hippest places in London, it is on the lips of authors and playwrights, and it found itself projected onto the side of a museum so it could confuse the British public en masse. As dead languages go, Polari is having a pretty fabulous afterlife and is now mixing with a much swankier set of posh queens. Who would have thought it?

Seriously, though, I’m glad that Polari is no longer seen as apolitical. In the pictures of Derek Jarman taken during his canonization, the look of pride and amusement on his face says it all. It’s perhaps the moment in Polari’s long, complicated history that I’m most proud of.

We’re pretty much caught up now, and there are only a few parts of Polari’s story left for me to tell. I’m afraid that the last chapter is going to get a bit preachy and weepy, so you might want to have a lace hanky at the ready for the big finish.