CHAPTER ONE

COURAGE

COURAGE

One isn’t necessarily born with courage, but one is born with potential. Without courage, we cannot practice any other virtue with consistency. We can’t be kind, true, merciful, generous or honest.

—Dr. Maya Angelou

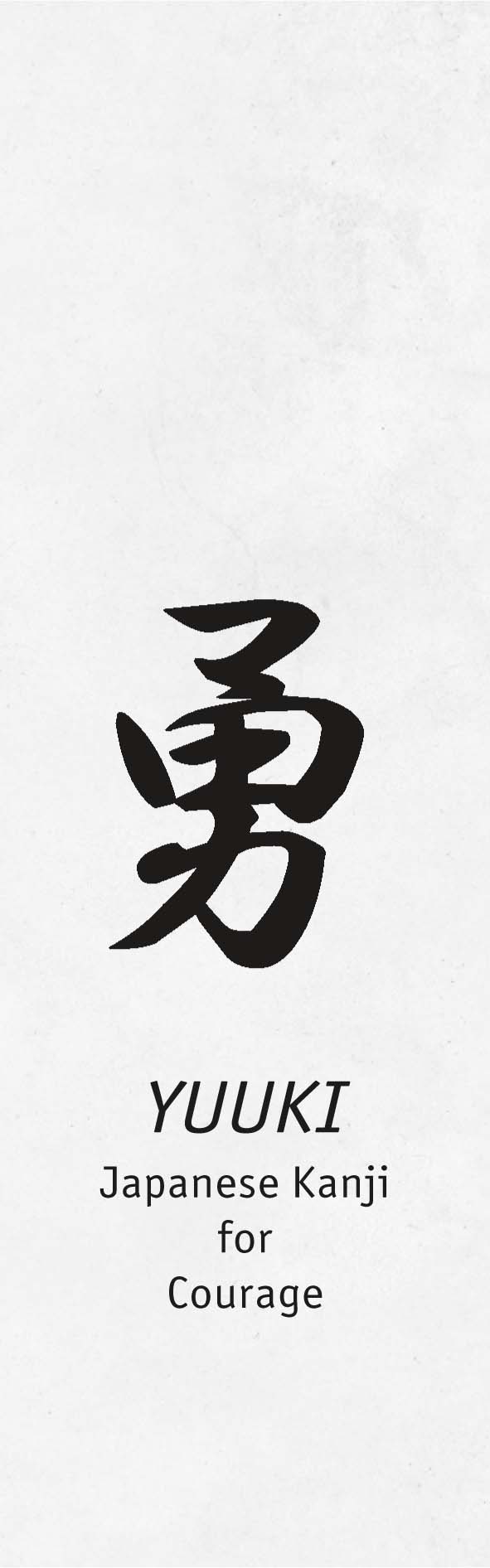

Webster describes courage as mental or moral strength to venture, persevere, and withstand danger, fear, or difficulty. In Japanese, yuuki is the kanji for the English word courage. Kanji is the ancient Japanese form of writing originally derived from the Chinese characters or ideograms. These ideograms were used to represent thoughts or objects. The combination of ideograms provided a means to convey more complex concepts, thoughts, ideas or expressions. This word yuuki is composed of two characters. The first kanji, yuu, means bravery or heroism. The second kanji, ki, means spirit or mind. Combined they give the Japanese equivalent of the English word courage. Yuuki is literally translated bravery of spirit.

It’s what my mom and dad called having guts; the ability to act, to take a chance, to engage…because deep inside there is something telling you there is more. There is something that everybody else overlooks: a chance to seize an opportunity or to just plain do what is right.

This concept of courage is the ability to confront hardship or danger and act rightly in the face of it. On occasion, this could entail ridicule, loss of relationships, personal and financial distress, imprisonment, and even death. What does it take to carry on with courage in the face of adversity? Why do some people have the tenacity to risk physical, mental, or personal danger to triumph over hardship?

There are different aspects of courage that range from risk of physical harm to mental endurance and resolve. Courage takes both physical and mental stamina to triumph over adversities. Courage is not reckless or negligent. One must take into consideration the dangers and risks involved in acting with courage. The courageous weigh the risks, and then act for the service of a greater cause.

From the beginning of time, stories of courage have inspired mankind. Examples are the biblical story of David, the young shepherd boy who dared to face the giant Goliath who defied the army and the God of Israel; and the Spartan king Leonidas who, with his small band of warriors, faced down the massive Persian army at Thermopylae and fought to the last man.

What is it that made these people different? Most noticeably they were warriors, willing to contend, to strive, and to persevere for something that they believed. These individuals are remembered for their physical courage. Each of us faces situations that challenge what we believe about our business, our dreams, and ourselves. It is this ability to strive and persevere in the face of these challenges that determines our level of courage.

The samurai warriors of Japan were willing to fight and die for their principles. They regarded their sacred duty to their lord more important than their own lives. Upholding the bushido code was their sole purpose in life.

People act courageously to protect lives daily: law enforcement, firefighters, and those serving, past and present, in our armed forces. We owe them much gratitude.

It is not only physical courage that we admire; we also admire mental and spiritual courage. Thomas Edison developed the light bulb after thousands of failures. Helen Keller, who became deaf and blind at a young age, dared to conquer her world of silence and darkness to pave the way for her own and future generations. Walt Disney and Colonel Sanders endured financial hardship, ridicule, and many rejections before realizing their dreams. In more recent times, you may recognize the name of Captain Chesley B. Sullenberger III, who courageously navigated his troubled aircraft to safety onto the Hudson River, saving the lives of all on board.

After being defeated in World War II, Japan rapidly directed its attention and energy to create new products and businesses. With samurai spirit and determination, Japan rose to be an economic superpower in a very short period of time. In awe, the rest of the world attempted to duplicate Japan’s achievements by studying its business methods.

The miracle that transformed war-ravaged Japan to a present-day economic powerhouse took courage on the part of the government, industry, and people. We saw this same courageous spirit acted out in the face of the tsunami on March 11, 2011. The level of devastation witnessed along the northeastern coast of Japan was heart wrenching. Yet, in spite of the loss of life and property, people summoned the courage and will to rebuild and continue. This samurai spirit inhabits the souls of modern-day Japan as surely as it did in the days of the shogun.

As you are about to read, the Japanese consul to Lithuania during the early days of World War II, Chiune Sugihara, faced the most difficult decision of his life. Did he obey the government of Japan, thereby denying transit visas for Jewish people to escape Nazi annihilation? Or did he obey the voice within directing him to do what he knew was right? What would you do in this situation? We are continually confronted with decisions that test our character. How do you summon the courage to make the decision that may take your business in a different direction? To enter uncharted waters that will change your life? It is often expedient doing what is easy, but is it the right or best thing for you?

As we saw in the Japanese kanji character for courage, there is a melding of bravery and spirit. We understand bravery because we see its manifestation in actions. The concept of spirit is not as easily grasped in terms of our physical world. Spirit, in this sense, is the intent behind the action. We might even say one’s intent produces the bravery or courage needed to perform the action. If you are struggling in a decision in your business or your personal life, examine the outcome you desire. Is your intent strong enough to muster the courage you need to take action?

Remember, courage is not being foolhardy, but rather a determination to succeed in spite of circumstances. Count the cost, but don’t let fear of failure be the determining factor. It is often better to try and fail than not try at all. The samurai was taught to control his fear and use it to motivate him to excel by focusing on the honor of his commitment. Like the samurai, you too can face your battles with courage.

I learned that courage was not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it.

The brave man is not he who does not feel afraid, but he who conquers it.

_______

—Nelson Mandela

Sugihara Family Kamon

Born on a cold and auspicious day—January 1, 1900—Chiune Sugihara was the second son of five boys and one girl born to Yoshimizu and Yatsu Sugihara, a middle-class samurai family.

Chiune Sugihara’s samurai heritage would influence his character and life’s path.

Sugihara was an outstanding student and a source of pride for his father. He graduated from high school with high honors. His father planned his future, desiring his enrollment in a prestigious medical school in Korea. At this point in history, Korea was occupied as part of Japan. Even though Sugihara disliked the sight of blood and would not choose to be a doctor himself, he tried to follow the mores of his time. Yoshimizu, his father, had the mindset that his son would be a doctor.

An important trait of a Japanese son or daughter is oya koko, to show respect for one’s parents. Not wanting to disappoint his father, Sugihara refrained from discussing his desire to learn and teach languages. He obediently went to the appointed medical school entrance examination even though he was in turmoil. Did he follow his father’s wishes or follow his heart’s desire to study foreign languages and travel the world?

On the medical entrance exam, Sugihara wrote his name on the exam paper but answered none of the questions indicating that he did not take the test. It took tremendous courage for him to defy his father and follow a different path. Up until this time, he was a model son. However, because of his disobedience, his father’s obligations to him ended.

Often, the status quo simply produces mediocrity. In order to grow, you may have to swim against the stream; this has its own risks. Mavericks may often fail, but that spirit within gives them the courage to rise again. Sugihara was a maverick, dared to be different, and acted upon what he knew was his life’s path. How many Japanese boys in that position, particularly at that time, would take such a risk? Today, how many people would be willing to risk everything to do what they know is the right thing? Are you willing to take such a risk?

Sugihara’s decision not to follow his father’s wishes took tremendous courage, particularly at this time in Japanese society. The samurai traditions were still evident, especially within the family hierarchy. He understood his mind and the path he was to follow. With true samurai determination, Sugihara followed what he thought was right for him. Through this one act, he risked not only loss of the financial support needed to further his education, but also the emotional support of his father and the culture at large. Few of us face such a potential life-altering decision at this young age. Would we have the courage to challenge the status quo, to risk it all to do what we know to be right in our heart? This went against everything he learned in childhood, because a good samurai is taught to obey orders.

Now on his own, Sugihara enrolled at Tokyo’s prestigious Waseda University in 1918 to study English literature. It was while he studied there that he answered an ad issued by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs seeking recruits. Potentially qualified candidates were encouraged to apply for possible recruitment. There were many requirements and difficult tests to pass; most candidates studied for two to three years. Instead, he had only several months to prepare and execute a plan to further his education. With samurai determination and intensive studying, he passed this difficult exam. He executed his plan with intelligence and courage. Sugihara would later write a manual that covered his method of studying and passing a test focusing on the importance of reading and developing vocabulary: A Letter from Harbin on a Snowy Day. His ability to prepare and execute a plan would serve him and humanity well by saving thousands of lives at a horrific time in history.

After passing the exam, Sugihara was sent to Harbin Gakuin in Manchuria where he taught Russian. Harbin Gakuin emphasized service to others, a philosophy that he embraced. He excelled in Russian, and this opened many doors. In 1920, he was drafted into the Japanese army. He spent one year in Korea during his year of mandatory military service.

In 1924, Sugihara returned to Harbin. He was hired by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where he served in the Russian section in Harbin. By 1932, his Russian proficiency made him a rising star within the Japanese governmental services. Shortly thereafter, the Manchurian foreign ministry hired him as an interpreter in the Russian section of the Manchurian foreign office. His next position was deputy representative of the same office.

By this time, the Japanese Imperial Army asserted a strong influence on the Manchurian Foreign Ministry and its policies. The sight of military brutality directed toward the Chinese civilian population became unbearable for Sugihara. He was faced with a decision to either further his career, or follow his conscience. Though pressured by superiors, once again he chose to do what he believed was right. His mind made up, Sugihara wrote a letter of protest against Japanese military brutality, and then he resigned his position.

We see in his actions Sugihara’s true character. We must remember that he made decisions at a time when Japanese nationalism was on the rise. He understood the risk he was taking regarding not only his career, but also perhaps his own life. In his actions, we see the underlying spirit of bushido on display. We understand in this one individual character trait the reason the samurai were fearsome yet noble individuals.

Sugihara returned to Japan in 1935. The Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs overlooked his resignation and hired him for ministry service. During his time in Japan he met and married Yukiko Kikuchi in 1936. She would be by his side throughout the coming ordeals.

Chiune and Yukiko Sugihara became the proud parents of their first son, Hiroki, a year after they were married. Shortly after Hiroki’s birth, the Sugihara family transferred to Finland, where Chiune was assigned as a translator at the legation in Helsinki. While stationed in Helsinki, they were delighted when their second son, Chiaki, was born.

After two years of service in Finland, Sugihara was reassigned to open up a consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania. At that time, there was turmoil and unrest throughout Europe. He was assigned to watch German activities along the Russian borders, and skilled in both Russian and German, he was the ideal person for the position. Their third son, Haruki, was born in Kaunas.

As Hitler tightened his reins around Eastern Europe, time was running out for Jewish peoples’ safety. By late July 1940, hundreds of Jewish refugees came from Poland to Lithuania, desperately trying to escape Nazi persecution. The refugees found their way to the Japanese consulate because they heard of the possibility of escaping annihilation by obtaining Japanese transit visas. Every day, frightened men, women and children pleaded desperately for their lives outside the Japanese consulate office.

Sugihara was faced with the most difficult decision in his life. Japanese tradition bound him to obedience, but he was a samurai taught to help those in need. He asked permission from the Japanese government three times to assist, but each time he was denied. If he disobeyed his government, he faced disgrace and dishonor. For him to disobey the government was an enormous undertaking that went completely against Japanese tradition. Also, to disobey would cause extreme financial hardship for his family, as well as risking their lives during a difficult time in history.

In order to reach their final destination, the refugees needed to pass through the Soviet Union. Chiune was able to negotiate an agreement with Soviet authorities allowing passage through Soviet territory as a result of the Japanese transit visa. This transit visa provided the Soviet required documentation necessary to exit Lithuania, travel across the Soviet Union and then exit the country for Japan. The negotiations took much skill and planning, similar to passing the exam for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The time to execute the plan was short, and the consequences significant.

Sugihara and Yukiko feared for their entire family. Making the decision to help would forever affect their lives; they could face a bleak future or government punishment. Both agreed they did not have a choice.

Sugihara embraced yuuki, literally meaning “bravery of spirit,” as his samurai ancestors had done. In the face of danger, he chose to stand for what he knew to be right regardless of the personal cost. He stood on the same foundational beliefs that guided the ancient samurai warriors of long ago.

In occupied Europe, thousands of Jews were being imprisoned and murdered each day. Because of the situation, Sugihara began to write transit visas on his own initiative in violation of his direct orders. From July 31 to September 4, 1940, he tirelessly handwrote transit visas for 18 to 20 hours per day. He produced a normal month’s worth of transit visas each day: 200 to 300 visas. Rarely stopping to eat or rest, he worked on the visas alone, not wanting to jeopardize his family. He did not allow Yukiko to get involved with the visas because he did not want her to be implicated.

Even a hunter cannot kill a bird that comes to him for refuge.

_______

Japanese Proverb

During the time Sugihara wrote the transit visas, the Soviet government insisted that he leave Kaunas, and the Japanese Foreign Ministry sent orders to close and vacate the embassy. He ignored both orders and continued to write visas in order to save the lives of Jewish refugees. The Japanese Foreign Ministry finally sent an urgent telegram demanding that he close the consulate, and then depart for Berlin because of Soviet orders closing consulates in Kaunas. With sad hearts, the Sugiharas realized it was time to leave.

Forty-five years after the Soviet annexation of Lithuania, Sugihara was asked his reasons for issuing transit visas to the Jews. He explained that the refugees were human beings, and that they simply needed help:

You want to know about my motivation, don’t you? Well. It is the kind of sentiments anyone would have when he actually sees refugees face to face, begging with tears in their eyes. He just cannot help but sympathize with them. Among the refugees were the elderly and women. They were so desperate that they went so far as to kiss my shoes, Yes, I actually witnessed such scenes with my own eyes. Also, I felt at that time, that the Japanese government did not have any uniform opinion in Tokyo. Some Japanese military leaders were just scared because of the pressure from the Nazis; while other officials in the home ministry were simply ambivalent.

People in Tokyo were not united. I felt it silly to deal with them. So, I made up my mind not to wait for their reply. I knew that somebody would surely complain about me in the future. But, I myself thought this would be the right thing to do. There is nothing wrong in saving many people’s lives…. The spirit of humanity, philanthropy…neighborly friendship…with this spirit, I ventured to do what I did, confronting this most difficult situation— and because of this reason, I went ahead with redoubled courage.1

After departing Lithuania, the Sugiharas travelled to Berlin, then Czechoslovakia, East Prussia, and finally Bucharest, Romania. They stayed in Bucharest until the end of World War II in 1945. Captured by Russian soldiers, the family was then incarcerated as prisoners of war in a Romanian prison camp for approximately 18 months.

During the cold, harsh winter of 1946, the Sugiharas were released and returned to Japan. Sadly, their youngest child, Haruki, died shortly after they arrived. It took approximately one and a half years to return to Japan because of hardships, delays, and uncertainties imposed by Soviet officials.

After returning to Japan, Sugihara hoped his career would continue. However, he was both humiliated and disappointed when asked by the ministry to resign. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs said they were downsizing because of the war. However, because of a private conversation, he surmised the action was related to the incident in Lithuania. In the Japanese culture, “saving face” is ingrained, and he grieved the humiliation extended toward his family, but always believed that he had done the right thing.

To support his family, Sugihara worked various jobs as a language tutor, manager for the U.S.-government-run PX, or Base Exchange store, and also as a door-to-door salesman. The family suffered hardships and lived in poverty until the early 1960s. He endeavored to persevere despite emotional and financial hardship. He wanted to do what was right and adhere to the samurai bushido code.

In the mid 1960s, Sugihara found employment as a branch manager for a Japanese trading company in the Soviet Union. The job required him to live in Moscow. For sixteen years he was separated from his family a majority of the time. He was able to visit the family twice per year, and he sent the greater part of his wages to Yukiko and his family. He endured much hardship and suffering to save those he loved, knowing he did the right thing.

In 1968, during one of his visits to Japan, Sugihara received an unexpected call from the Israeli Embassy. A Mr. Nishri, an attaché for the Israeli Embassy, was visiting Japan and desired to meet Sugihara. Nishri was a Jewish representative who sought exit transit visas in Lithuania during World War II. He showed Sugihara the visa that he had issued 28 years earlier. Mr. Nishri had been searching for Sugihara for many years to thank him for saving his life. Although Nishri inquired earlier if others had been saved by the visas, the Japanese government said they had no information. It was an emotional reunion for both men and Sugihara realized that his efforts were not in vain. He later rejoiced when he learned that most of the recipients of the visas had survived!

It is recorded that Sugihara wrote over 2,000 transit visas during the summer of 1940, resulting in saving over 6,000 lives. Among the survivors was the entire Mirrer Yeshiva, a Jewish institute for religious studies, comprised of over 300 students and staff. Mirrer Yeshiva was the only yeshiva whose entire membership survived the Holocaust. In March 2015, Nobuki Sugihara, youngest son of Chiune Sugihara visited the Mirrer Yeshiva in Brooklyn, New York. Today it is estimated there are over 100,000 descendants of these transit visa recipients who owe their lives to Chiune Sugihara and his family.

If you save the life of one person, it is as if you saved the entire world.

_______

The Talmud

On November 29, 1984, Chiune Sugihara (aka Sempo Sugihara) was awarded Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem The World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. This award is given to non-Jewish people who risked their lives to aid Jews during the Holocaust. The motivation must have been to help Jews rather than for personal gain. He became the first Asian to receive this award. His wife, Yukiko, and his son, Hiroki, accepted the honor on his behalf because he was not strong enough to travel. In Jerusalem, trees were planted in Sugihara’s name, and a park was named in his honor.

In Yaotsu (Gifu Prefecture), a monument and a museum documenting his courageous efforts were built in his honor. Completed in 1992, this project was appropriately named the Hill of Humanity.

During a trip to Japan in October 2010, my husband and I visited the Hill of Humanity in Yaotsu, Japan. It was a deeply moving experience that still continues to affect me. On display were pictures, visas, and mementos that told Chiune Sugihara’s story of how he saved so many Jewish refugees; he was a truly courageous samurai. As I walked among the many artifacts, I realized that principles do matter and these can change individuals, businesses, and societies for the better far beyond a lifetime. He counted the cost: he knew in his heart what he had to do, and because of what he believed to be true, he had the courage to act.

At times, you may think “I’m only one person” and feel that you or your contribution are insignificant. However, we see that because of Sugihara’s courageous act, thousands of lives were spared and many are affected even today. We all have a calling in our lives, and everyone’s gift to humanity is important. It is not your job to compare, but be faithful to what you are given.

If you were offered all of the riches in the world under one condition, would you take it? What if the condition would be for you to give up your sight, smell, touch, thought, speech, hearing, and your taste? Would you still take it? How would you survive and function in this world? What would your life be like? In asking this question to my audiences, there has not been one person who would make the trade. You are so valuable; in fact, you are priceless! When you realize your worth, the world around you looks different, and you see people in a new light.

I first learned of Chiune Sugihara at the Wing Luke Museum in 1994 in Seattle, and his story left a profound impression on me. His life and acts of courage inspired me to write this book and visit Yaotsu in October 2010. I am thankful that we visited the memorial museum and Hill of Humanity, because I now have a fuller understanding and greater appreciation of Chiune Sugihara and his worldly impact.

Most important, Sugihara was a samurai warrior, yet he did not handle a gun or sword. He brought about change without going to battle. He was strategic, yet peaceful; decisive yet compassionate; and determined yet gentle. He was a peaceful warrior, and not every warrior has to be a battlefield-hardened soldier to be a true warrior and a hero. There are many positive attributes in Chiune Sugihara’s life that you can emulate. Which one(s) would you choose?

Sugihara understood his purpose in life at an early age, lived accordingly, and pursued opportunities in line with his purpose and values. He did not take the medical school entrance exam, because he knew that was not his purpose in life. He resigned from assignments that he disagreed with because of people’s mistreatment. He counted the costs knowing that his decision could mean his death, but he felt pity for the refugees knowing without his help they had little hope for survival. Are you willing to count the cost to fulfill your life purpose?

From Chiune Sugihara’s story, you learned about doing the right thing and acting on your principles. It took more than physical courage for Sugihara to write the visas knowing his life was in jeopardy. This act also took emotional and spiritual courage. By acting on your principles, you lay a foundation for a solid life with vital relationships. If I asked you if you had a code of honor that you lived by, could you name the elements of your honor code?

Courage takes many forms. Sugihara lived a life of courage. Unlike most, he knew what was right and had the courage to act on his convictions. As we see from his story, courage is not always easy, but it has its own rewards. Chiune Sugihara died knowing that in the face of great danger, he did the right thing!

And most important, have the courage to follow your intuition.

_______

Steve Jobs

Foot Note

1. Wikipedia Online, “Chiune Sugihara” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chiune_Sugihara